Solid-State NMR Study of New Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolytes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

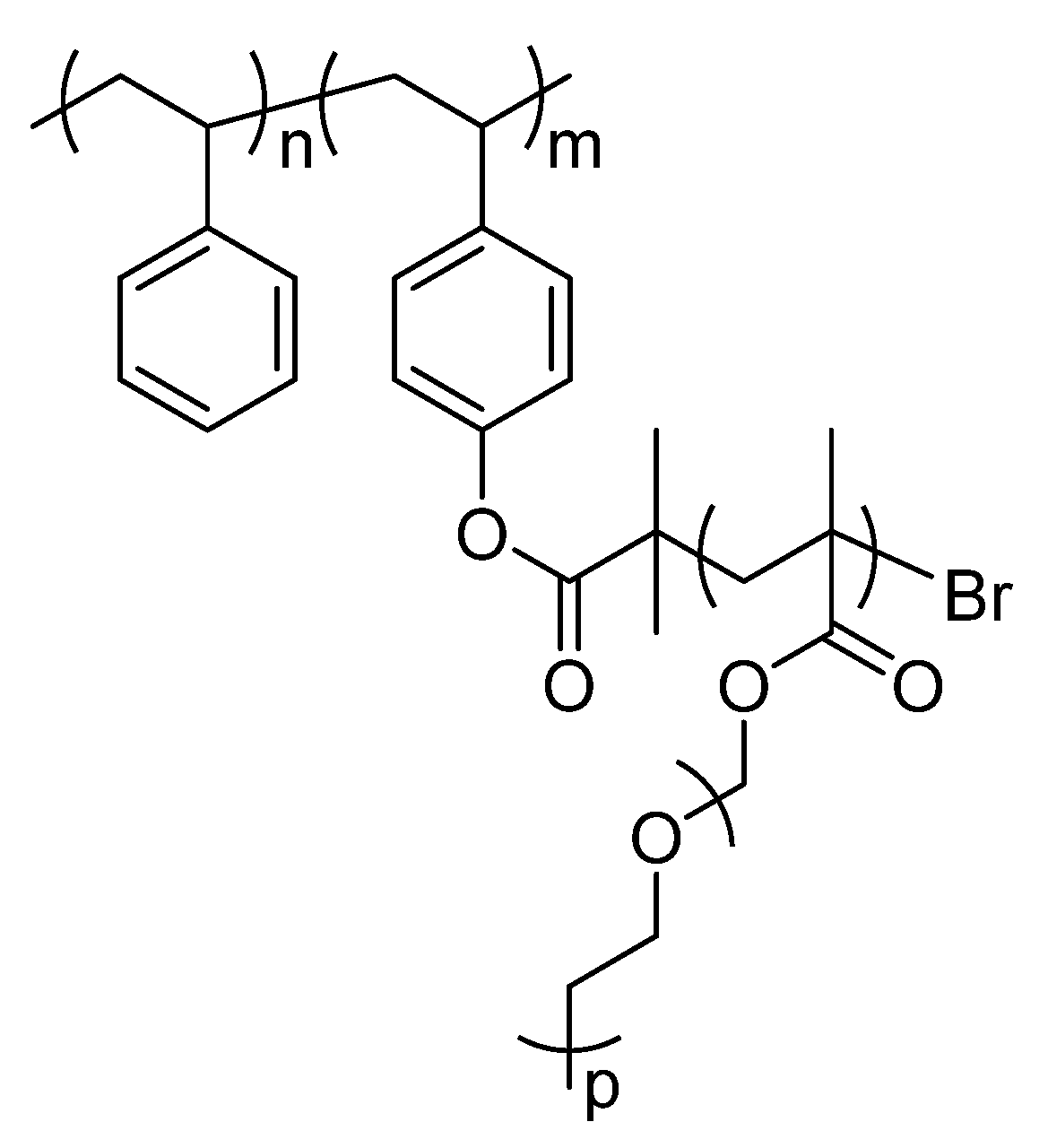

2.1. Description of Polymers Investigated by Solid-State NMR

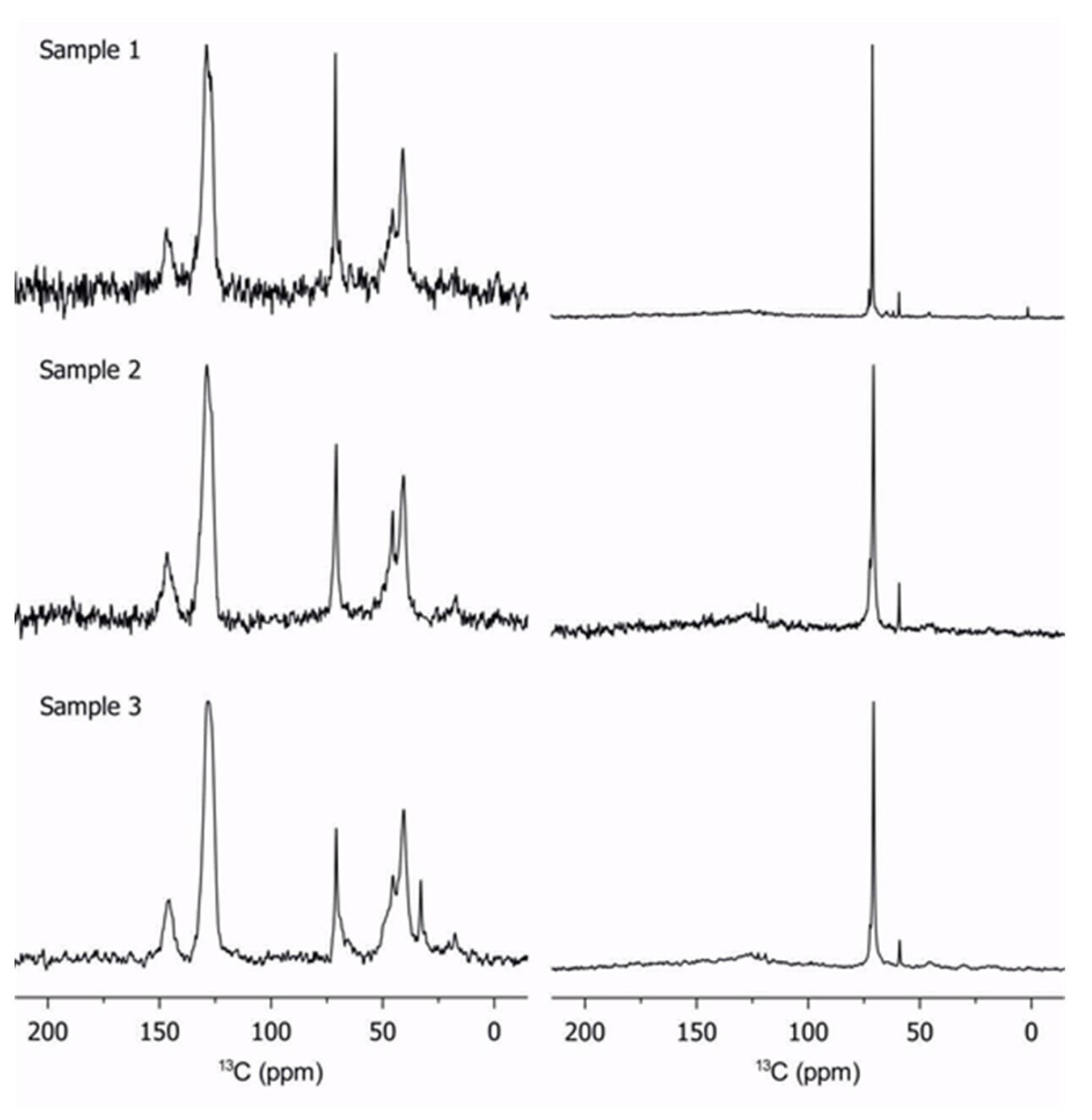

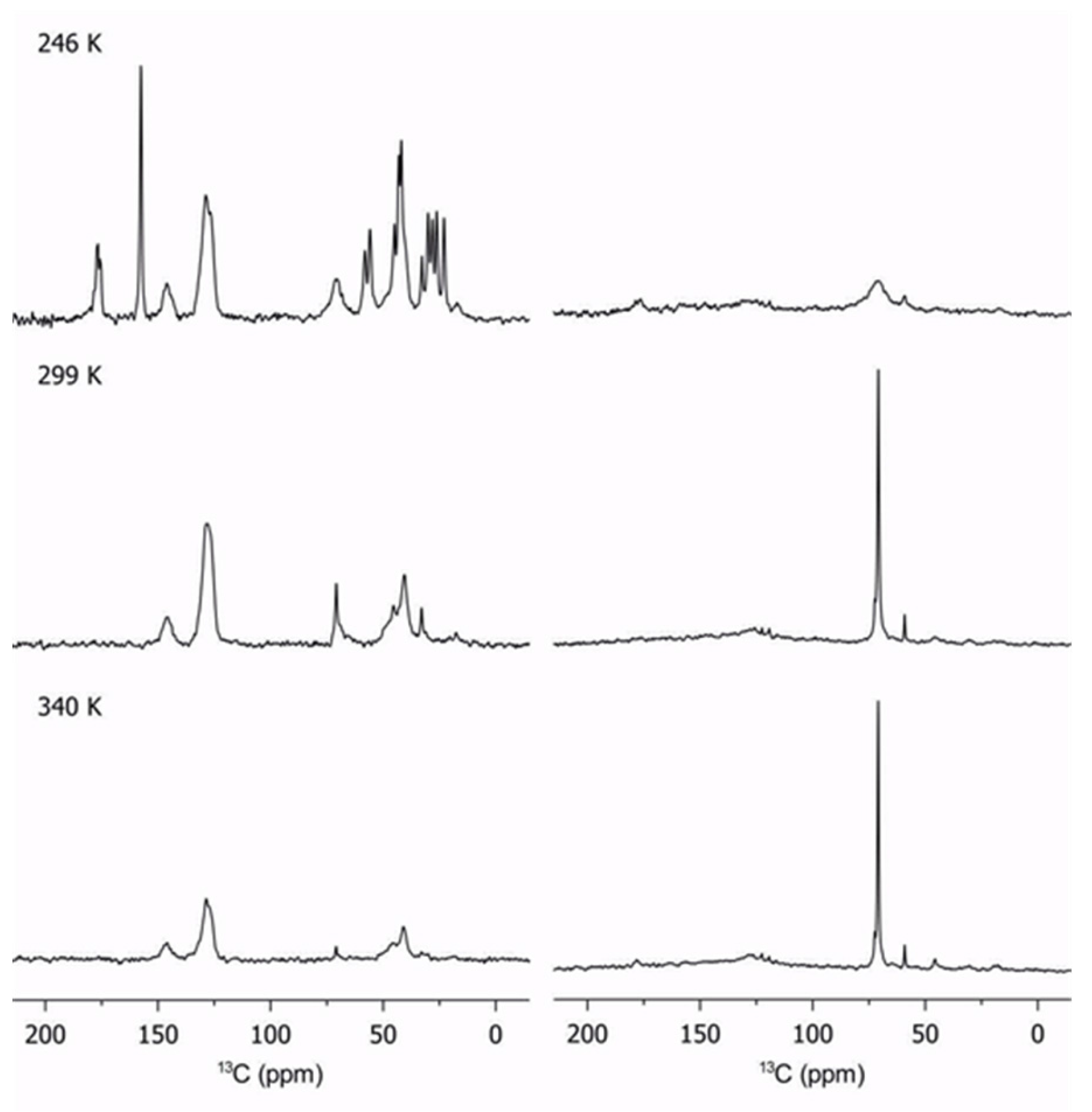

2.2. Characterization of Copolymers by 13C Solid-State NMR

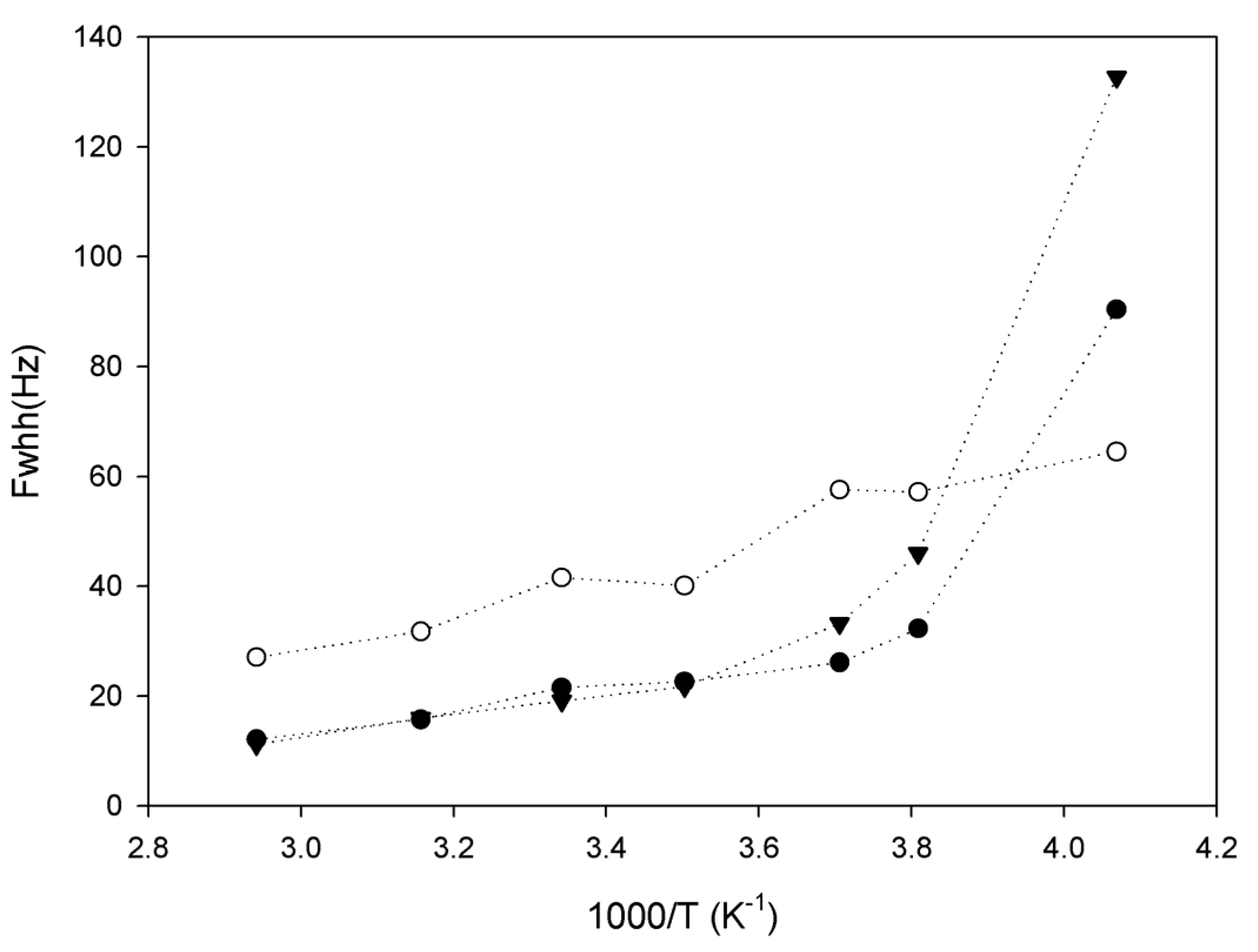

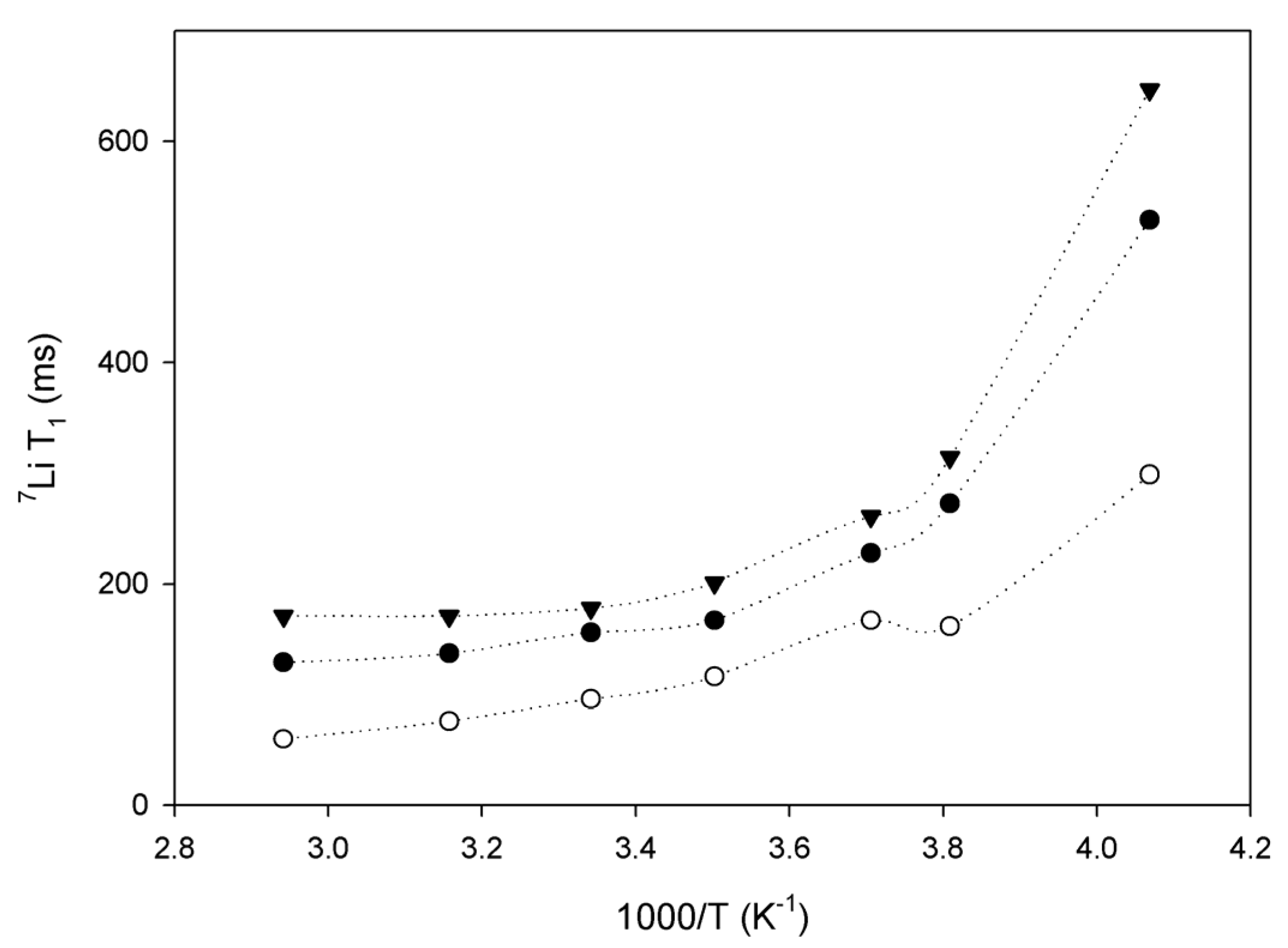

2.3. Lithium Diffusion in the Membranes by 7Li Solid-State NMR

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Murata, K.; Izuchi, S.; Yoshihisa, Y. An overview of the research and development of solid polymer electrolyte batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2000, 45, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarascon, J.M.; Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, A.; Raymond, N.; Armand, M. Runaway risk of forming toxic compounds. Nature 2003, 424, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthiram, A.; Yu, X.; Wang, S. Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.V. Electrical conductivity in ionic complexes of poly(ethylene oxide). Br. Polym. J. 1975, 7, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, M.B.; Chabagno, J.M.; Duclot, M.J. Polyethers as Solid Electrolytes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Marzantowicz, M.; Dygas, J.R.; Krok, F.; Florjańczyk, Z.; Zygadło-Monikowska, E. Influence of crystalline complexes on electrical properties of peo: Litfsi electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 53, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Odusanya, O.; Wilmes, G.M.; Eitouni, H.B.; Gomez, E.D.; Patel, A.J.; Chen, V.L.; Park, M.J.; Fragouli, P.; Iatrou, H.; et al. Effect of molecular weight on the mechanical and electrical properties of block copolymer electrolytes. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 4578–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; Newman, J. Dendrite growth in lithium/polymer systems: A propagation model for liquid electrolytes under galvanostatic conditions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150, A1377–A1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; Newman, J. The impact of elastic deformation on deposition kinetics at lithium/polymer interfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, A396–A404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, R.; Maria, S.; Meziane, R.; Aboulaich, A.; Lienafa, L.; Bonnet, J.-P.; Phan, T.N.T.; Bertin, D.; Gigmes, D.; Devaux, D.; et al. Single-ion bab triblock copolymers as highly efficient electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daigle, J.-C.; Vijh, A.; Hovington, P.; Gagnon, C.; Hamel-Pâquet, J.; Verreault, S.; Turcotte, N.; Clément, D.; Guerfi, A.; Zaghib, K. Lithium battery with solid polymer electrolyte based on comb-like copolymers. J. Power Sources 2015, 279, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaluenga, I.; Inceoglu, S.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.C.; Chintapalli, M.; Wang, D.R.; Devaux, D.; Balsara, N.P. Nanostructured single-ion-conducting hybrid electrolytes based on salty nanoparticles and block copolymers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Stone, G.M.; Balsara, N.P.; Zuckermann, R.N. Structure–conductivity relationship for peptoid-based peo–mimetic polymer electrolytes. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5151–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, D.; Glé, D.; Phan, T.N.T.; Gigmes, D.; Giroud, E.; Deschamps, M.; Denoyel, R.; Bouchet, R. Optimization of block copolymer electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4682–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorecki, W.; Jeannin, M.; Belorizky, E.; Roux, C.; Armand, M. Physical properties of solid polymer electrolyte PEO(LiTFSI) complexes. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1995, 7, 6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-L.; Kao, H.-M.; Wu, R.-R.; Kuo, P.-L. Multinuclear solid-state nmr, dsc, and conductivity studies of solid polymer electrolytes based on polyurethane/poly(dimethylsiloxane) segmented copolymers. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 3083–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayamizu, K.; Akiba, E.; Bando, T.; Aihara, Y.; Price, W.S. Nmr studies on poly(ethylene oxide)-based polymer electrolytes with different cross-linking doped with LIN(SO2CF3)2. Restricted diffusion of the polymer and lithium ion and time-dependent diffusion of the anion. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 2785–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-Y.; Wei, D.-X.; Xu, M.; Yao, Y.-F.; Chen, Q. Transferring lithium ions in nanochannels: A PEO/Li+ solid polymer electrolyte design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3631–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harry, K.J.; Hallinan, D.T.; Parkinson, D.Y.; MacDowell, A.A.; Balsara, N.P. Detection of subsurface structures underneath dendrites formed on cycled lithium metal electrodes. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daigle, J.-C.; Asakawa, Y.; Vijh, A.; Hovington, P.; Armand, M.; Zaghib, K. Exceptionally stable polymer electrolyte for a lithium battery based on cross-linking by a residue-free process. J. Power Sources 2016, 332, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiess, H.W. Molecular motion, phase separation and internal surfaces in rubber-elastic polymers. Angew. Makromol. Chem. 1992, 202–203, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiess, H.W.; Schmidt-Rohr, K. Multidimensional solid-state NMR studies of chain motions in polymers. Polym. Prepr. (Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Polym. Chem.) 1992, 33, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bluemich, B.; Bluemich, P.; Guenther, E.; Jansen, J.; Schauss, G.; Spiess, H.W. NMR Imaging of Polymers: Methods and Applications; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bluemich, B.; Bluemler, P.; Guenther, E.; Spiess, H.W. Methods and applications of NMR imaging in polymer research. Polym. Prepr. (Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Polym. Chem.) 1992, 33, 759–760. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Ratio PEGMA/PS b | Mn (g mol−1) c | Tg1 (K) d | Tg1Li (K) d | σ at 60 °C (10−4S cm−1) e | Capacity (mA hg−1) f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.6 | 140,500 | 211 | 224 | 2.54 | 146 |

| 2 | 3.9 | 103,000 | 216 | 227 | 1.44 | 144 |

| 3 | 30 | 1,200,000 | 212 | 225 | nd | nd |

| ID | Ea (kJ mol−1) a | Ea (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 | 11 |

| 2 | 45 | 21 |

| 3 | nd | 20 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daigle, J.-C.; Arnold, A.A.; Vijh, A.; Zaghib, K. Solid-State NMR Study of New Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Magnetochemistry 2018, 4, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry4010013

Daigle J-C, Arnold AA, Vijh A, Zaghib K. Solid-State NMR Study of New Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Magnetochemistry. 2018; 4(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry4010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaigle, Jean-Christophe, Alexandre A. Arnold, Ashok Vijh, and Karim Zaghib. 2018. "Solid-State NMR Study of New Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolytes" Magnetochemistry 4, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry4010013

APA StyleDaigle, J.-C., Arnold, A. A., Vijh, A., & Zaghib, K. (2018). Solid-State NMR Study of New Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Magnetochemistry, 4(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry4010013