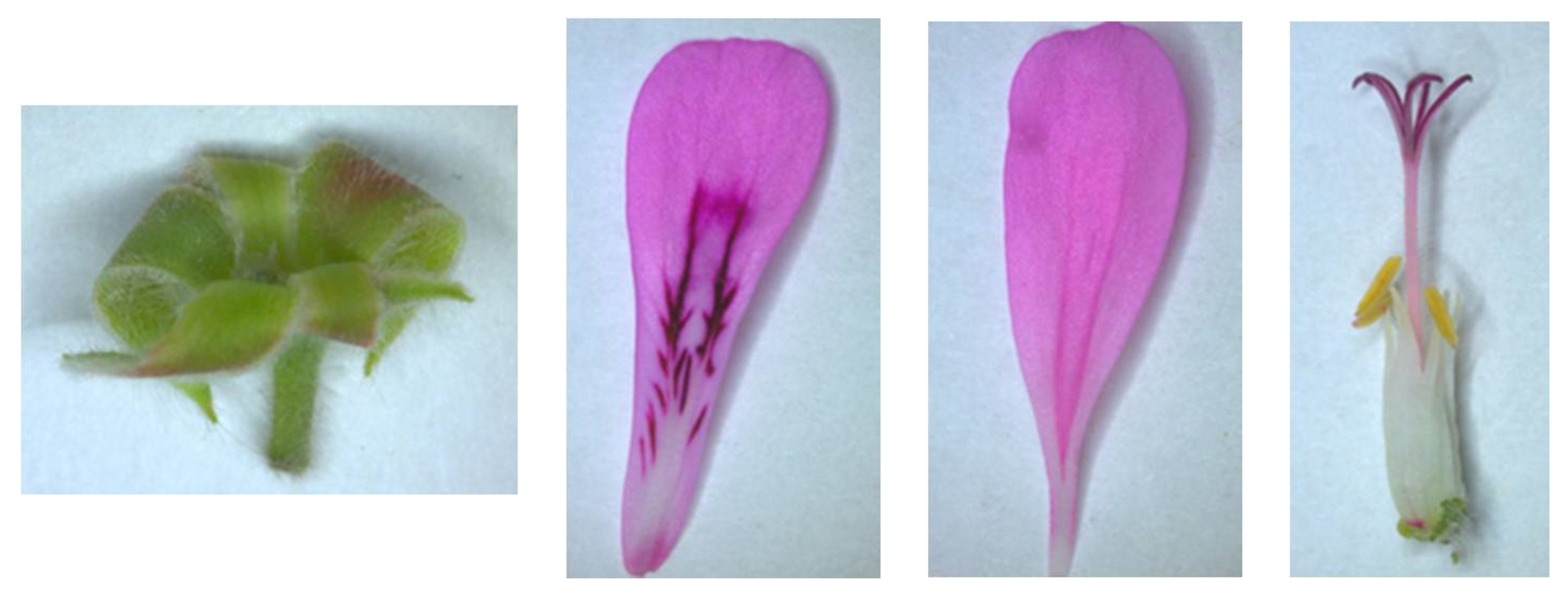

Phytochemicals and Volatiles in Developing Pelargonium ‘Endsleigh’ Flowers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

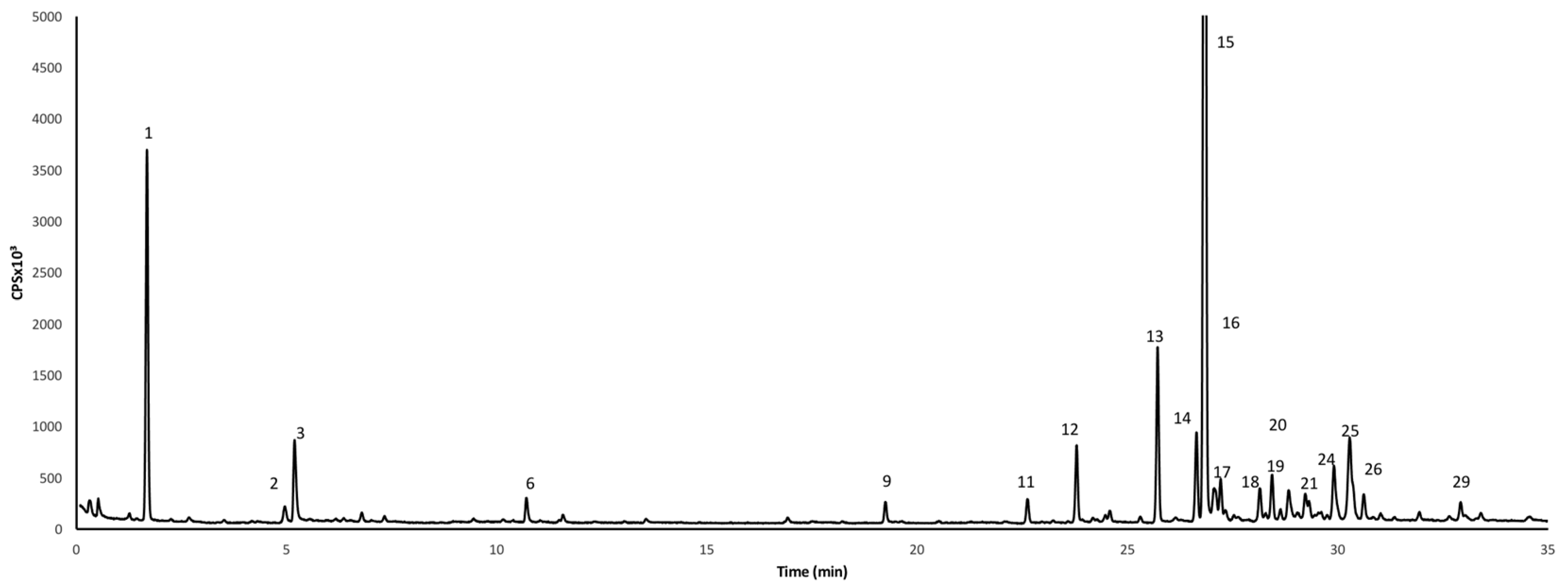

3.1. Phenols and Organic Compounds in P. ‘Endsleigh’ Flowers

3.2. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

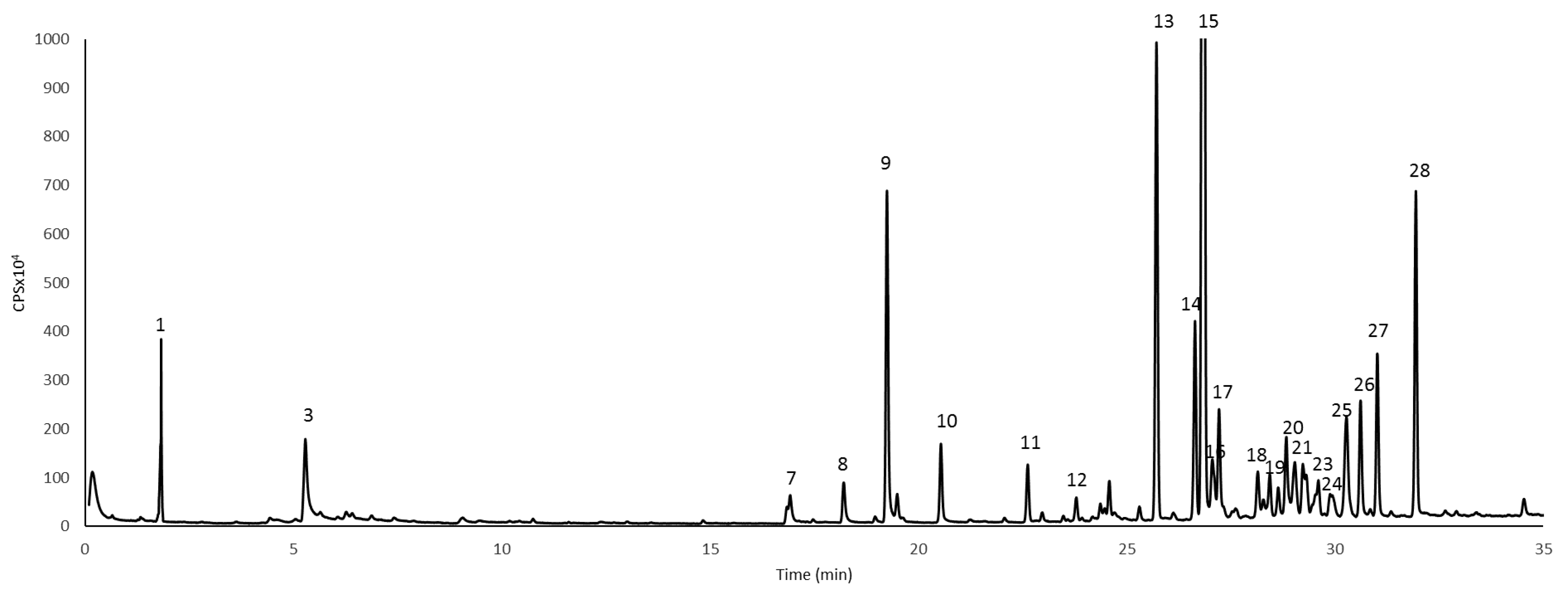

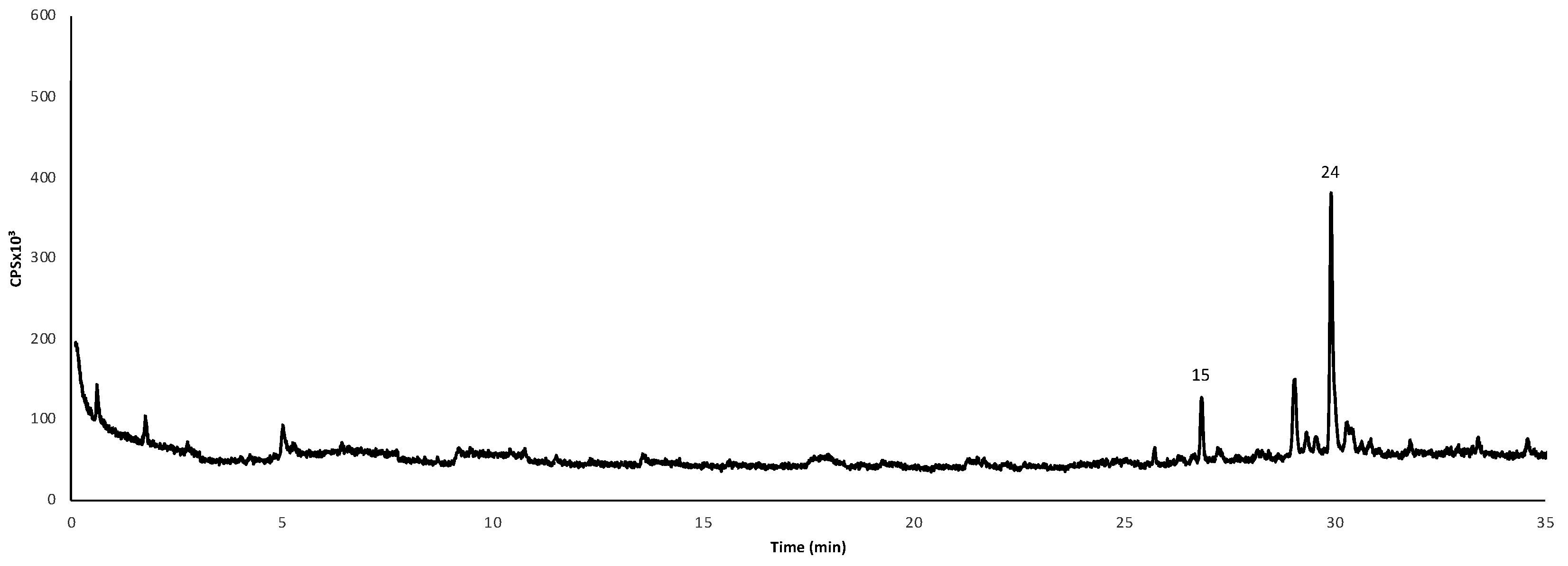

3.3. Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Whole Flowers

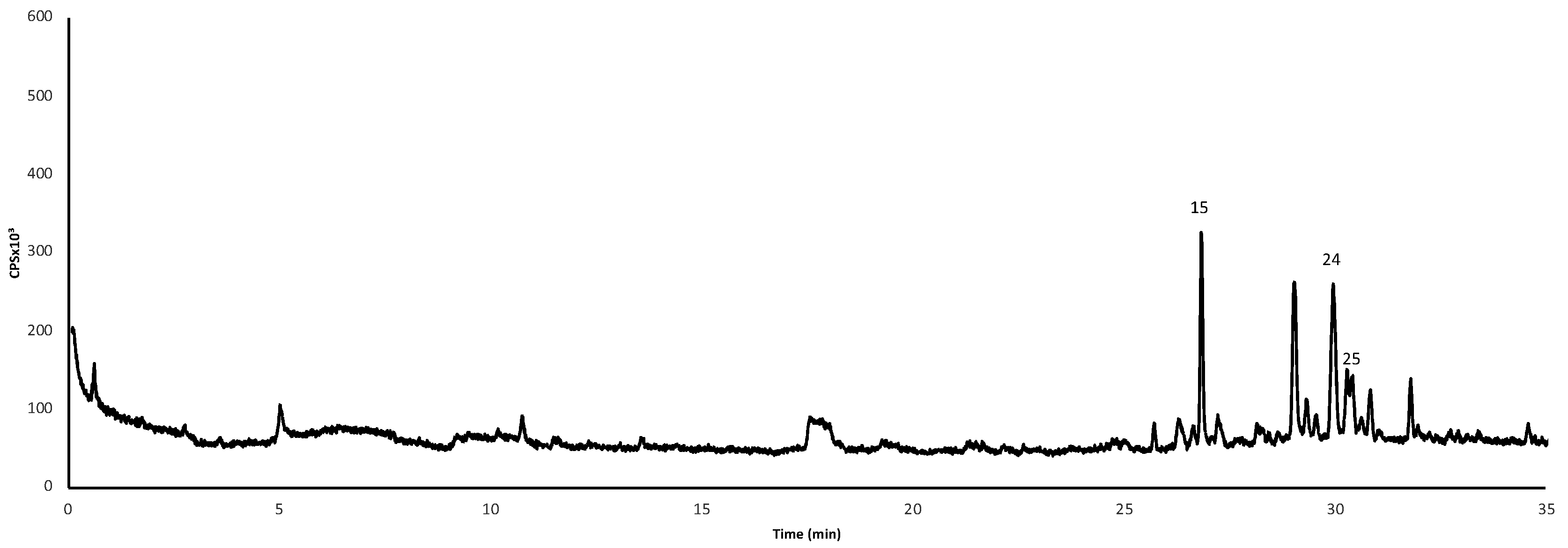

3.4. Volatile Organic Compoundsproduced by Sepals, Petals and Stamens/Pistils

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eilers, E.J.; Kleine, S.; Eckert, S.; Waldherr, S.; Müller, C. Flower Production, Headspace Volatiles, Pollen Nutrients, and Florivory in Tanacetum vulgare Chemotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 611877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Mazzoncini, M. The Biodiversity of Edible Flowers: Discovering New Tastes and New Health Benefits. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 569499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demasi, S.; Mellano, M.G.; Falla, N.M.; Caser, M.; Scariot, V. Sensory Profile, Shelf Life, and Dynamics of Bioactive Compounds during Cold Storage of 17 Edible Flowers. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Herb Society of America. Pelargoniums: An Herb Society of America Guide. 2006. Available online: https://www.herbsociety.org/file_download/inline/2b2f9fc8-e827-446c-99da-1c1e8b6559d0 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Deane, G. (2007–2012) Edible Flowers: Part Ten. Available online: http://www.eattheweeds.com/edible-flowers-part-ten/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Lauderdale, C.; Bradley, L. Choosing and Using Edible Flowers; North Carolina State University Extension: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2019; Available online: http://content.ces.ncsu.edu/choosing-and-using-edible-flowers-ag-790 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Lim, T.K. Edible Medicinal and Non Medicinal Plants, Volume 8, Flowers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R. Aromatic Pelargoniums. Arnoldia 1974, 34, 97–124. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42962527 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Just Geraniums. Available online: https://justgeraniums.weebly.com/store/p16/Scented_Plant_4_-_Pelargonium_Endsleigh_Spice.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Pichersky, E.; Gershenzon, J. The formation and function of plant volatiles: Perfumes for pollinator attraction and defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, B. Consumer acceptance of fruit and vegetables: The role of flavour and other quality attributes. In Fruit and Vegetable Flavour: Recent Advances and Future Prospects, 1st ed.; Brückner, B., Wyllie, S.G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2008; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database; NIST Standard Reference Database Number 101; Johnson, R.D., III, Ed.; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, W.; Fang, X.; Su, S.; Peng, W. Differential volatile organic compounds in royal jelly associated with different nectar plants. J. Int. Agric. 2016, 15, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Negro, C.; Aprile, A.; De Bellis, L.; Miceli, A. Nutraceutical Properties of Mulberries Grown in Southern Italy (Apulia). Antioxidants 2019, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Negro, C.; Sabella, E.; Nicolì, F.; Pierro, R.; Materazzi, A.; Panattoni, A.; Aprile, A.; Nutricati, E.; Vergine, M.; Miceli, A.; et al. Biochemical Changes in Leaves of Vitis vinifera cv. Sangiovese Infected by Bois Noir Phytoplasma. Pathogens 2020, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oki, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Nakamura, T.; Okuyama, A.; Masuda, M.; Shiratusuchi, H.; Suda, I. Changes in radical-scavenging activity and components of mulberry fruit during maturation. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, C18–C22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma as measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattivi, F.; Arapitsas, P.; Perenzoni, D.; Vrhovsek, U. L’analisi metabolomica descrive come cambia la composizione del vino durante la micro-ossigenazione, sotto l’effetto combinato di ossigeno e ferro. In La Ricerca Applicata ai Vini di Qualità; Di Blasi, S., Ed.; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2012; pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ma, R.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Chen, F.; Wang, Z. Identification and quantification of anthocyanins in Kyoho grape juice-making pomace, Cabernet Sauvignon grape winemaking pomace and their fresh skin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, C.M. The biochemistry of organic acid in the grape. In The Biochemistry of the Grape Berry; Geros, H., Chaves, M.M., Delrot, S., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2012; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen, A.; Toivonen, E.; Mutikainen, P.; Salminen, J.-P. Defensive strategies in Geranium sylvaticum, Part 1: Organ-specific distribution of watersoluble tannins, flavonoids and phenolic acids. Phytochemistry 2013, 95, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sayed, E.; Martiskainen, O.; Seif el-Din, S.H.; Sabra, A.-N.A.; Hammam, O.A.; El-Lakkany, N.M. Protective effect of Pelargonium graveolens against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice and characterization of its bioactive constituents by HPLC–PDA–ESI–MS/MS analysis. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandrić, Z.; Frew, R.D.; Fernandez-Cedi, L.N.; Cannavan, A. An investigative study on discrimination of honey of various floral and geographical origins using UPLC-QToF MS and multivariate data analysis. Food Control 2017, 72, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, P.; Jing, P.; Yue, J.; Yu, L. Chromatographic Fingerprint Analysis and Rutin and Quercetin Compositions in the Leaf and Whole-Plant Samples of Di- and Tetraploid Gynostemma pentaphyllum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3042–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Grimalt, M.; Legua, P.; Almansa, M.S.; Amorós, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Hernández, F. Polyphenol Compounds and Biological Activity of Caper (Capparis spinosa L.) Flowers Buds. Plants 2019, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Afsheen, N.; Khalil-ur-Rehman; Jahan, N.; Ijaz, M.; Manzoor, A.; Khan, K.M.; Hina, S. Cardioprotective and Metabolomic Profiling of Selected Medicinal Plants against Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 9819360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boukhris, M.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Sayadi, S.; Bouaziz, M. Chemical composition and biological activities of polar extracts and essential oil of rose-scented geranium, Pelargonium graveolens. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioni, I.; Pistelli, L.; Ferri, B.; Copetta, A.; Ruffoni, B.; Pistelli, L.; Najar, B. Phytonutritional Content and Aroma Profile Changes During Postharvest Storage of Edible Flowers. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 590968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozan, B.; Ozek, T.; Kurkcuoglu, M.; Kirimer, N.; Can Baser, K.H. The analysis of essential oil and headspace volatiles of the flowers of Pelargonium endlicherianum used as an anthelmintic in folk medicine. Planta Med. 1999, 65, 781–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Williams, C.A. Phytochemistry of the genus Geranium. In Geranium and Pelargonium; Lis-Balchin, M., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2002; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen, A. Tannins and Other Polyphenols in Geranium sylvaticum: Identification, Intraplant Distribution and Biological Activity. Doctoral Thesis, University of Turku, Turku, Finland, December 2017. Available online: https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/144333 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Demasi, S.; Caser, M.; Donno, D.; Enri, S.R.; Lonati, M.; Scariot, V. Exploring wild edible flowers as a source of bioactive compounds: New perspectives in horticulture. Folia Hortic. 2021, 33, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janarny, G.; Ranaweera, K.K.D.S.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P. Antioxidant activities of hydro-methanolic extracts of Sri Lankan edible flowers. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 35, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y. Laboratory and field investigation on the orientation of Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) to more suitable host plants driven by volatiles and component analysis of volatiles. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Howell, K.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, P. Sesquiterpenes in grapes and wines: Occurrence, biosynthesis, functionality, and influence of winemaking processes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 247–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- The Good Scents Company Information System. Available online: http://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/index.html (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- El-Sayed, A.M. The Pherobase: Database of Pheromones and Semiochemicals. 2021. Available online: https://www.pherobase.com (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Nishida, R.; Shelly, T.E.; Whittier, T.S.; Kaneshiro, K.Y. α-Copaene, a potential rendezvous cue for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata? J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, I.; Shalit, M.; Menda, N.; Piestun, D.; Dafny-Yelin, M.; Shalev, G.; Weiss, D. Rose scent genomics approach to discovering novel floral fragrance-related genes. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 2325–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudareva, N.; Pichersky, E. Floral scent metabolic pathways: Their regulation and evolution. In Biology of Floral Scent; Dudareva, N., Pichersky, E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parachnowitsch, A.L.; Raguso, R.A.; Kessler, A. Phenotypic selection to increase floral scent emission, but not flower size or colour in bee-pollinated Penstemon digitalis. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulia, O.; Ahmadia, N.; Rashidi Monfared, S.; Sefidkon, F. Physiological, phytochemicals and molecular analysis of color and scent of different landraces of Rosa damascena during flower development stages. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 231, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z. Volatile Organic Compounds Emissions from Luculia pinceana Flower and Its Changes at Different Stages of Flower Development. Molecules 2016, 21, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Wan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Ma, H.; Liu, X.; He, R.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z. Floral Scent Chemistry of Luculia yunnanensis (Rubiaceae), a Species Endemic to China with Sweetly Fragrant Flowers. Molecules 2017, 22, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiaoying, L.; JunKai, W.; Haijing, W.; Hongxia, Z.; Xuemin, G. Analysis of volatile components in whorl tepals of Magnolia denudata ‘feihuang’ during its development. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2019, 46, 2009–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lyu, S.; Chen, D.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, G.; Ye, N. Volatiles Emitted at Different Flowering Stages of Jasminum sambac and Expression of Genes Related to α-Farnesene Biosynthesis. Molecules 2017, 22, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mus, A.A.; Gansau, J.A.; Kumar, V.S.; Rusdi, N.A. The variation of volatile compounds emitted from aromatic orchid (Phalaenopsis bellina) at different timing and flowering stages. Plant Omics 2020, 13, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, P.; Chakrabarti, S.; Gaikwad, N.K.; Kutty, N.N.; Barman, M.; Mitra, A. Developmental variation in floral volatiles composition of a fragrant orchid Zygopetalum maculatum (Kunth) Garay. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | Formula [M-H]− | m/z Exp | m/z Calc | Error ppm | Score | Compound Name | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C4H5O6 | 149.0072 | 149.0092 | 13.31 | 78 | * Tartaric acid | [19,20] |

| 2 | C4H6O5 | 133.0120 | 133.0142 | 17.27 | 76 | * Malic acid | [21] |

| 3 | C13H15O10 | 331.0714 | 331.067 | −13.3 | 79 | Monogalloylhexose | [22] |

| 4 | C4H8O5 | 135.0292 | 135.0299 | 5.05 | 85 | unknow | - |

| 5 | C17H15O7 | 331.0795 | 331.0823 | 8.66 | 80 | unknow | - |

| 6 | C14H18O9 | 329.0910 | 329.0878 | −9.72 | 75 | Methylated protocatechuic acid hexose | [23] |

| 7 | C25H22O8 | 449.123 | 449.1242 | 2.62 | 81 | Flavanone hexoside | [23] |

| 8 | C23H34O17 | 581.1691 | 581.1723 | 5.59 | 79 | Methyl syringate 4-O-β-d-gentiobiose (Leptosperin) | [24] |

| 9 | C24H17O9 | 479.0860 | 479.0831 | −6.05 | 75 | * Myricetin 3-O-glucoside | [23] |

| 10 | C20H17O12 | 449.0856 | 449.0878 | 4.94 | 78 | unknow | - |

| 11 | C30H44O21 | 739.2288 | 739.2302 | 1.91 | 85 | Kaempferol 3-O-di-p-coumaroylhexoside | [25] |

| 12 | C25H19O9 | 463.1032 | 463.1035 | 0.54 | 85 | Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside | [26] |

| 13 | C30H44O21 | 739.2286 | 739.2302 | 2.18 | 80 | Kaempferol 3-O-di-p-coumaroylhexoside | [25] |

| 14 | C25H20O9 | 463.1033 | 463.1035 | 0.38 | 85 | Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside is. II | [26] |

| 15 | C31H30O12 | 593.1682 | 593.1664 | −3 | 79 | Proanthocyanidin | [27] |

| 16 | C24H18O8 | 433.0919 | 433.0929 | 2.38 | 78 | Quercetin 3-O-pentoside | [23] |

| 17 | C21H19O11 | 447.0949 | 447.0933 | −3.13 | 86 | * Kaempferol 3-O-galactoside | [23] |

| 18 | C21H19O11 | 447.0962 | 447.0933 | −5.46 | 85 | * Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | [23] |

| 19 | C24H18O7 | 417.0954 | 417.0980 | 2.8 | 78 | Kaempferol 3-O-pentoside | [23] |

| 20 | C22H16O5 | 359.0883 | 359.0925 | 3.8 | 79 | unknow | - |

| Floral Development Stage | TPC | |

|---|---|---|

| mg GAE/g FW | mg GAE/g DW | |

| Mature bud | 33.9 ± 1.5 a | 154.2 ± 6.8 a |

| Full bloom | 28.3 ± 1.4 b | 128.0 ± 6.7 b |

| Senescing | 32.1 ± 1.5 a | 145.1 ± 6.5 a |

| Floral Development Stage | 1 Myricetin 3-O-glucoside | 2 Kaempferol3-O-di-p-coumaroyl-hexoside | 1 Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 3 Quercetin 3-O-pentoside |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature bud | 7.4 ± 0.5 a | 7.8 ± 0.3 a | 6.0 ± 0.3 b | 3.6 ± 0.6 a |

| Full bloom | 8.1 ± 0.8 a | 6.2 ± 0.4 b | 6.3 ± 0.8 ab | 3.8 ± 0.9 a |

| Senescing | 8.7 ± 0.7 a | 5.1 ± 0.5 b | 7.4 ± 0.7 a | 4.6 ± 1.2 a |

| Floral Development Stage | DPPHTE (µmol/g DW) | FRAPTE (µmol/g DW) | Superoxide AnionIC50 (g DW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mature bud | 7.1 ± 1.8 a | 44 ± 5 c | 0.92 ± 0.04 b |

| Full bloom | 10.0 ± 1.6 a | 69 ± 4 a | 0.88 ± 0.07 b |

| Senescing | 7.1 ± 1.6 a | 57 ± 4 b | 1.13 ± 0.03 a |

| No. | RI | Compound Name | ng/g FW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature Bud | Full Bloom | Senescing | |||

| 1 | 1011 | 3-Carene | 18.08 ± 5.8 | 34.77± 4.1 | 21.29 ± 5.6 |

| 2 | 1035 | unknow | 0 | 2.26 ± 1.9 | 0 |

| 3 | 1038 | unknow | 3.85 ± 1.5 | 9.42 ± 3.5 | 3.52 ± 2.5 |

| 4 | 1040 | unknow | 0 | 0 | 1.14 ± 0.6 |

| 5 | 1044 | β-Ocimene | 0 | 0 | 1.25 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 1114 | Fenchol | 4.87 ± 1.7 | 2.50 ± 1.2 | 0 |

| 7 | 1228 | Ctronellol | 0 | 0 | 2.47 ± 0.5 |

| 8 | 1250 | unknow | 0 | 0 | 0.86 ± 0.3 |

| 9 | 1276 | 6-Octen-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-formate | 2.44 ± 1.2 | 2.09 ± 1.4 | 3.38 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 1310 | unknow | 0 | 0 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| 11 | 1351 | α-Cubebene | 3.87 ± 1.3 | 2.49 ± 1.5 | 1.41 ± 1.4 |

| 12 | 1358 | α-Copaene | 31.70 ± 3.4 | 7.97 ± 1.4 | 3.21 ± 1.4 |

| 13 | 1420 | β-Caryophyllene | 28.53 ± 3.7 | 16.97 ± 2.6 | 8.21 ± 1.4 |

| 14 | 1439 | α-Guaiene | 13.89 ± 1.4 | 9.14 ± 1.1 | 4.93 ± 1.0 |

| 15 | 1445 | Guaia-6-9 diene | 232.44 ± 11.7 | 169.98 ± 21.7 | 83.88 ± 13.8 |

| 16 | 1451 | Aristolene | 7.85 ± 2.1 | 5.67 ± 1.7 | 1.27 ± 1.2 |

| 17 | 1454 | Humulene | 7.00 ± 1.3 | 4.46 ± 1.2 | 1.60 ± 0.5 |

| 18 | 1477 | γ-Himachalene | 4.96 ± 1.4 | 3.24 ± 1.7 | 0.95 ± 0.3 |

| 19 | 1481 | Germacrene D | 11.24 ± 1.9 | 4.43 ± 1.3 | 2.87 ± 1.8 |

| 20 | 1490 | β-Guaiene | 6.52 ± 2.1 | 3.69 ± 1.4 | 1.66 ± 1.1 |

| 21 | 1494 | δ-selinene | 7.11 ± 1.3 | 2.48 ± 1.3 | 1.66 ± 1.2 |

| 22 | 1497 | α-Muurolene | 4.53 ± 1.4 | 0 | 1.02 ± 0.6 |

| 23 | 1502 | unknow | 0 | 0 | 10.11 ± 1.7 |

| 24 | 1512 | unknow | 12.24 ± 1.9 | 7.45 ± 1.7 | 2.56 ± 1.5 |

| 25 | 1519 | Cadina-1(10),4-diene | 21.49 ± 3.5 | 14.52 ± 1.6 | 6.49 ± 1.9 |

| 26 | 1521 | unknow | 11.25 ± 1.9 | 2.91 ± 1.1 | 7.63 ± 1.8 |

| 27 | 1529 | Citronellyl butyrate | 3.89 ± 1.2 | 0 | 3.32 ± 1.7 |

| 28 | 1533 | unknow | 6.32 ± 1.6 | 0 | 5.91 ± 1.4 |

| 29 | 1542 | unknow | 0 | 2.66 ± 1.2 | 1.05 ± 1.0 |

| Total amount | 444.07 | 309.10 | 184.75 | ||

| No. | R.I. | Compound Name | ng/g FW |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1011 | 3-Carene | 75.19 ± 12.3 |

| 3 | 1038 | unknow | 26.23 ± 1.8 |

| 7 | 1228 | citronellol | 8.27 ± 1.4 |

| 8 | 1250 | unknow | 10.2 ± 1.2 |

| 9 | 1276 | 6-Octen-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-formate | 69.48 ± 1.9 |

| 10 | 1310 | unknow | 23.73 ± 2.7 |

| 11 | 1351 | α-Cubebene | 11.99 ± 2.2 |

| 12 | 1358 | α-Copaene | 5.28 ± 1.8 |

| 13 | 1420 | β-Caryophyllene | 97.69 ± 7.3 |

| 14 | 1439 | α-Guaiene | 41.37 ± 5.2 |

| 15 | 1445 | Guaia-6-9 diene | 503.39 ± 25.7 |

| 16 | 1451 | Aristolene | 18.51 ± 2.5 |

| 17 | 1454 | Humulene | 26.16 ± 2.7 |

| 18 | 1477 | γ-Himachalene | 10.86 ± 5.2 |

| 19 | 1481 | Germacrene D | 10.44 ± 3.7 |

| 20 | 1490 | β-Guaiene | 21.10 ± 2.4 |

| 21 | 1494 | δ-selinene | 9.24 ± 2.2 |

| 23 | 1502 | unknow | 10.11 ± 2.0 |

| 24 | 1512 | unknow | 10.23 ± 2.1 |

| 25 | 1519 | Cadina-1(10),4-diene | 32.03 ± 3.6 |

| 26 | 1521 | unknow | 24.70 ± 4.1 |

| 27 | 1529 | Citronellyl butyrate | 32.47 ± 5.3 |

| 28 | 1533 | unknow | 65.41 ± 7.1 |

| Total amount | 1045.16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negro, C.; Dimita, R.; Min Allah, S.; Miceli, A.; Luvisi, A.; Blando, F.; De Bellis, L.; Accogli, R. Phytochemicals and Volatiles in Developing Pelargonium ‘Endsleigh’ Flowers. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110419

Negro C, Dimita R, Min Allah S, Miceli A, Luvisi A, Blando F, De Bellis L, Accogli R. Phytochemicals and Volatiles in Developing Pelargonium ‘Endsleigh’ Flowers. Horticulturae. 2021; 7(11):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110419

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegro, Carmine, Rosanna Dimita, Samar Min Allah, Antonio Miceli, Andrea Luvisi, Federica Blando, Luigi De Bellis, and Rita Accogli. 2021. "Phytochemicals and Volatiles in Developing Pelargonium ‘Endsleigh’ Flowers" Horticulturae 7, no. 11: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110419

APA StyleNegro, C., Dimita, R., Min Allah, S., Miceli, A., Luvisi, A., Blando, F., De Bellis, L., & Accogli, R. (2021). Phytochemicals and Volatiles in Developing Pelargonium ‘Endsleigh’ Flowers. Horticulturae, 7(11), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110419