Aquaponics in Urban Agriculture: Social Acceptance and Urban Food Planning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Groups (FG#1–3)

- Focus Group #1 (FG#1); n = 8

- Focus Group #2 (FG#2); n = 9

- Focus Group #3 (FG#3); n = 7

2.2. Key Informant Interviews (KI#1–18)

2.3. Scenario Analyses (SA#1–7)

3. Results

3.1. Part 1: Perception of Aquaponics

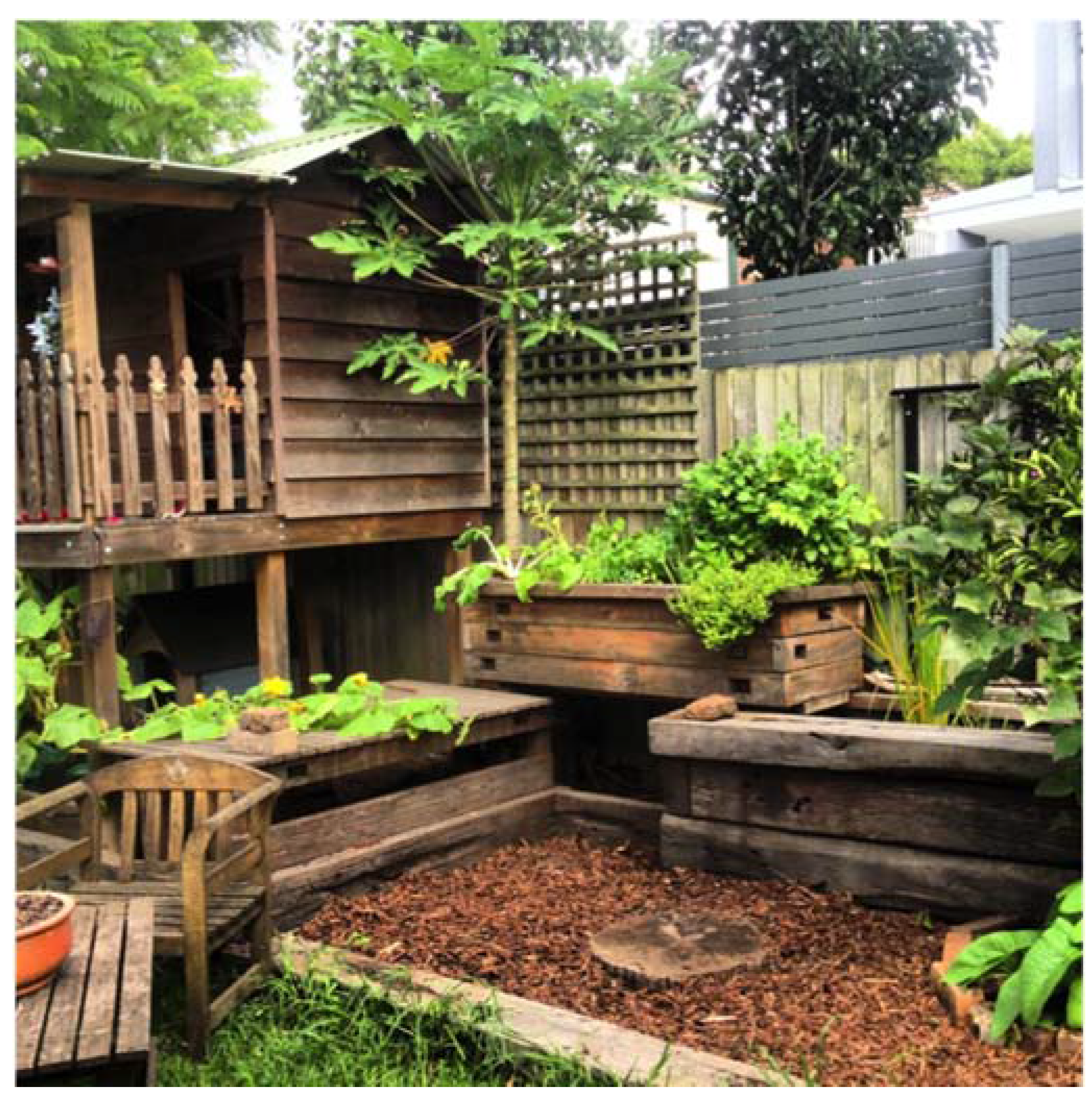

“The aesthetics of the backyard systems are exciting” FG#1 and “I like the experimental side.”FG#1

“Seems to have the scope to scale up, so why hasn’t it happened?” FG#1 and “I’d really miss the earth and all the things that are in the earth that feed my plants.”FG#3

“I think my honest gut reaction is suspicion” FG#3 and “[I’m] interested in looking at a future of energy constraints; aquaponics looks very energy and material based.”FG#2

3.1.1. Barriers

3.1.2. Benefits or Value

3.1.3. Business Considerations

“I think people need to touch and feel and smell. They need to see it working. To get close to it, to understand it.”KI#1

“If I went to a farmers’ market and there was a lettuce for sale, could I distinguish between one grown using aquaponics or conventionally? If trying to sell it—as a consumer, why would I choose one over the other?”KI#2

“Selling the story. Differentiated, e.g., selling Kingfish to Sydney restaurants. I had to say why it was special and only available through here… …You’re selling food, not a fish.”KI#3

3.1.4. Scaled Guidelines

3.2. Part 2: Urban Planning

3.2.1. Focus Group and Interview Responses to Urban Food Planning

“I think it’s much better just to fly under the radar as long as you can.”FG#3

3.2.2. Top Down Support

“If the government supports something or doesn’t, there can be a policy vacuum. You have to have a high-level policy position. From these you can build programs and under them particular projects. But you need the driver up top.”KI#2

“In terms of the farmers themselves, if you’re small-scale, PIRSA helps in terms of over-arching policies and things but doesn’t get involved in the day to day… So if you’re small, you either become a member of a body that can represent you or you just do your own thing and not worry about anyone else.”KI#15

3.2.3. Improving Urban Food Planning

“[We] already have a big push for ‘Place Making’ where the community leads the way and the Council works to support them in their endeavours and provide a little bit of structure and just make sure it’s safe.”SA#1

“I think it’s going to be more push than pull as in the community is going to have to push the council into asking for space rather than the council being proactive and saying ‘we’re going to give you this’.”KI#15

3.2.4. Scenario Analysis

“This sort of thing keeps the food local which is good. Food security is associated with your environmental footprint, so we want to encourage people to keep it local.”SA#7

“We don’t get too involved in growing food… Unfortunately bound by legislation with little room to move. If there is a justified complaint then that must result in instant action.”SA#6

“The Council no longer considers any community garden proposal to be established on Council property for the life of the Council.”SA#2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gittleman, M.; Jordan, K.; Brelsford, E. Using citizen science to quantify community garden crop yields. Cities Environ. (CATE) 2012, 5, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bendt, P.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J. Civic greening and environmental learning in public-access community gardens in berlin. Landscape Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Ecological citizenship and sustainable consumption: Examining local organic food networks. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B. Embodied connections: Sustainability, food systems and community gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A. Small Farms as a Planetary Ecological Asset: Five Key Reasons Why We Should Support the Revitalisation of Small Farms in the Global South; Third World network (TWN): Penang, Malaysia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, S. Urban Agriculture Impacts: Social, Health, and Economic: A Literature Review; UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program, Agricultural Sustainability Institute at UC Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lennard, W. Aquaponics: The integration of recirculating aquaculture and hydroponics. World Aquacult. 2009, 40, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S. Aquaponic Gardening: A Step-by-Step Guide to Raising Vegetables and Fish Together; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Le Blond, J. Rooftop Fish Farms to Feed Germany’s Sprawling Urban Population. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/jun/04/rooftop-fish-farms-german-population (accessed on 4 May 2014).

- Love, D.C.; Fry, J.P.; Li, X.; Hill, E.S.; Genello, L.; Semmens, K.; Thompson, R.E. Commercial aquaponics production and profitability: Findings from an international survey. Aquaculture 2015, 435, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakocy, J.E.; Timmons, M.B.; Ebeling, J.M. Chapter 19. Aquaponics: Integrating fish and plant culture. In Recirculating Aquaculture, 2nd ed.; Cayuga Aqua Ventures, LLC: Freeville, NY, USA, 2007; p. 860. [Google Scholar]

- Goddek, S.; Delaide, B.; Mankasingh, U.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; Jijakli, H.; Thorarinsdottir, R. Challenges of sustainable and commercial aquaponics. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4199–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, D.C.; Fry, J.P.; Genello, L.; Hill, E.S.; Frederick, J.A.; Li, X.; Semmens, K. An international survey of aquaponics practitioners. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroel, M.; Junge, R.; Komives, T.; König, B.; Plaza, I.; Bittsánszky, A.; Joly, A. Survey of aquaponics in europe. Water 2016, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.R. Aquaponics: Community and Economic Development; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miličić, V.; Thorarinsdottir, R.; Santos, M.D.; Hančič, M.T. Commercial aquaponics approaching the european market: To consumers’ perceptions of aquaponics products in europe. Water 2017, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, C.; Tait, C. Adelaide: Nature of a City: The Ecology of a Dynamic City 1836–2036; BioCity: Centre for Urban Habitats, University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, C.; Hodgson, J. Adelaide: Water of a City; Wakefield Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Planning Institute of Australia (SA Division). Submission on the Draft 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide; Planning Institute of Australia (SA Division): Adelaide, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, K.; Arman, M. Planning for sustainability: An assessment of recent metropolitan planning strategies and urban policy in Australia. Aust. Plan. 2014, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Feeding the city: The challenge of urban food planning. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, T.; Slade, C. Integrating Land Use Planning and Community Food Security; The Victorian Local Government Association: Melbourne, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, W.; Collett, A.; Ludlow, T.; Sinclair, I.; Whitehead, J. Planning and Food Security within the Commonwealth: Discussion Paper; Commonwealth Association of Planners, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, V. Planning for Urban Agriculture Planning in Australian Cities. In Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities Conference (SOAC) 5, Melbourne, Australia, 29 November–2 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DeLind, L.B. Place, work, and civic agriculture: Common fields for cultivation. Agric. Hum. Values 2002, 19, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A. Focus Groups. Available online: http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU19.html (accessed on 12 June 2014).

- Richards, L.; Morse, J. Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.; Krueger, R. When to use focus groups and why. In Focus Groups as Qualitative Research; Morgan, D., Ed.; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Montello, D.; Sutton, P. An Introduction to Scientific Research Methods in Geography and Environmental Studies; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.; Casey, M.A. Social Analysis Selected Tools and Techniques: Designing and Conducting Focus Group Interviews; Social Development Department of the World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.; Pade, J. Aquaponic Food Production: Growing Fish and Vegetables for Food and Profit; Nelson and Pade, Inc.: Montello, WI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Cachia, M.; Millward, L. The telephone medium and semi-structured interviews: A complementary fit. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 6, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, S. Telephone versus face-to-face interviews mode effect on semistructured interviews with children. Soc. Method 2013, 43, 133–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, R.V.; Treadwell, D.D.; Simonne, E.H. Opportunities and challenges to sustainability in aquaponic systems. Horttechnology 2011, 21, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pothukuchi, K.; Kaufman, J.L. Placing the food system on the urban agenda: The role of municipal institutions in food systems planning. Agric. Hum. Values 1999, 16, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, H.; Carlisle, R.; Bernardi, A.; McConell, K. Building an appetite for food in planning. Plan. News 2013, 39, 14. [Google Scholar]

| Literature 1 Based Strengths | Focus Group Based Strengths | Literature 1 Based Weaknesses | Focus Group Based Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Structure | Suitable for |

|---|---|

| 1. Backyard scale | One family |

| Two families (sharing) | |

| 2. Community | Community garden |

| Community collective | |

| 3. Limited niche market | Farmers market |

| Restaurants | |

| 4. Social enterprise | Unemployment work program |

| Migrant support program | |

| Home-based sales | |

| Youth training | |

| 5. Large wholesale commercial | Wholesale to supermarket |

| Commercial partner | |

| 6. Food garden service | Part of garden design and build business |

| Fishponds | |

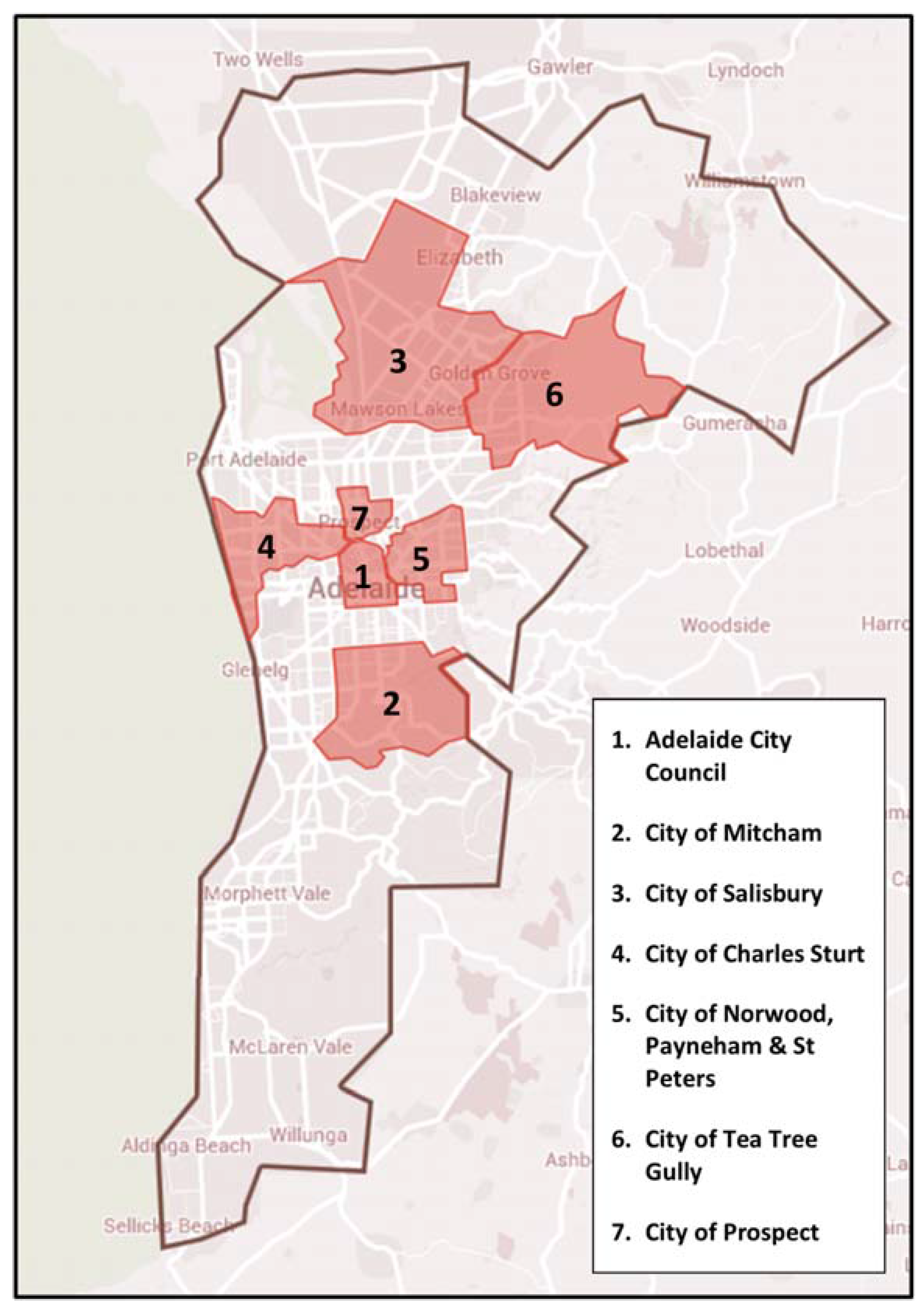

| Detailed stipulations about the depth, development approval, safety, and intensiveness of the fish keeping. | Charles Sturt |

| Norwood, Payneham, and St. Peters | |

| Vague. Would probably be okay, but… (not front garden and check Planning Department). | Adelaide |

| Tea Tree Gully | |

| Prospect | |

| No response to fishponds/no mention online. | Mitcham |

| Salisbury | |

| Community Garden | |

| Have community gardens on council land in their area. | Every Council except Mitcham. |

| Mentioned keeping “fish” in the community garden, but must consider scale and application requirements. | Charles Sturt |

| Tea Tree Gully | |

| Small Home Business | |

| Full guidelines for two separate sized scales: (1) A home activity; (2) A shop selling goods. | Norwood, Payneham, and St. Peters |

| Unsure. Could depend on scale (e.g., no more than 30 m2 or 10% of block). Need to speak with Environmental Health or PIRSA and look up SA Food Act 2001. | Adelaide |

| Charles Sturt | |

| Tea Tree Gully | |

| No response to home business/no mention online. | Mitcham |

| Salisbury | |

| Prospect | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pollard, G.; Ward, J.D.; Koth, B. Aquaponics in Urban Agriculture: Social Acceptance and Urban Food Planning. Horticulturae 2017, 3, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae3020039

Pollard G, Ward JD, Koth B. Aquaponics in Urban Agriculture: Social Acceptance and Urban Food Planning. Horticulturae. 2017; 3(2):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae3020039

Chicago/Turabian StylePollard, Georgia, James D. Ward, and Barbara Koth. 2017. "Aquaponics in Urban Agriculture: Social Acceptance and Urban Food Planning" Horticulturae 3, no. 2: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae3020039

APA StylePollard, G., Ward, J. D., & Koth, B. (2017). Aquaponics in Urban Agriculture: Social Acceptance and Urban Food Planning. Horticulturae, 3(2), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae3020039