A Review of Key Technologies and Recent Advances in Intelligent Fruit-Picking Robots

Abstract

1. Introduction

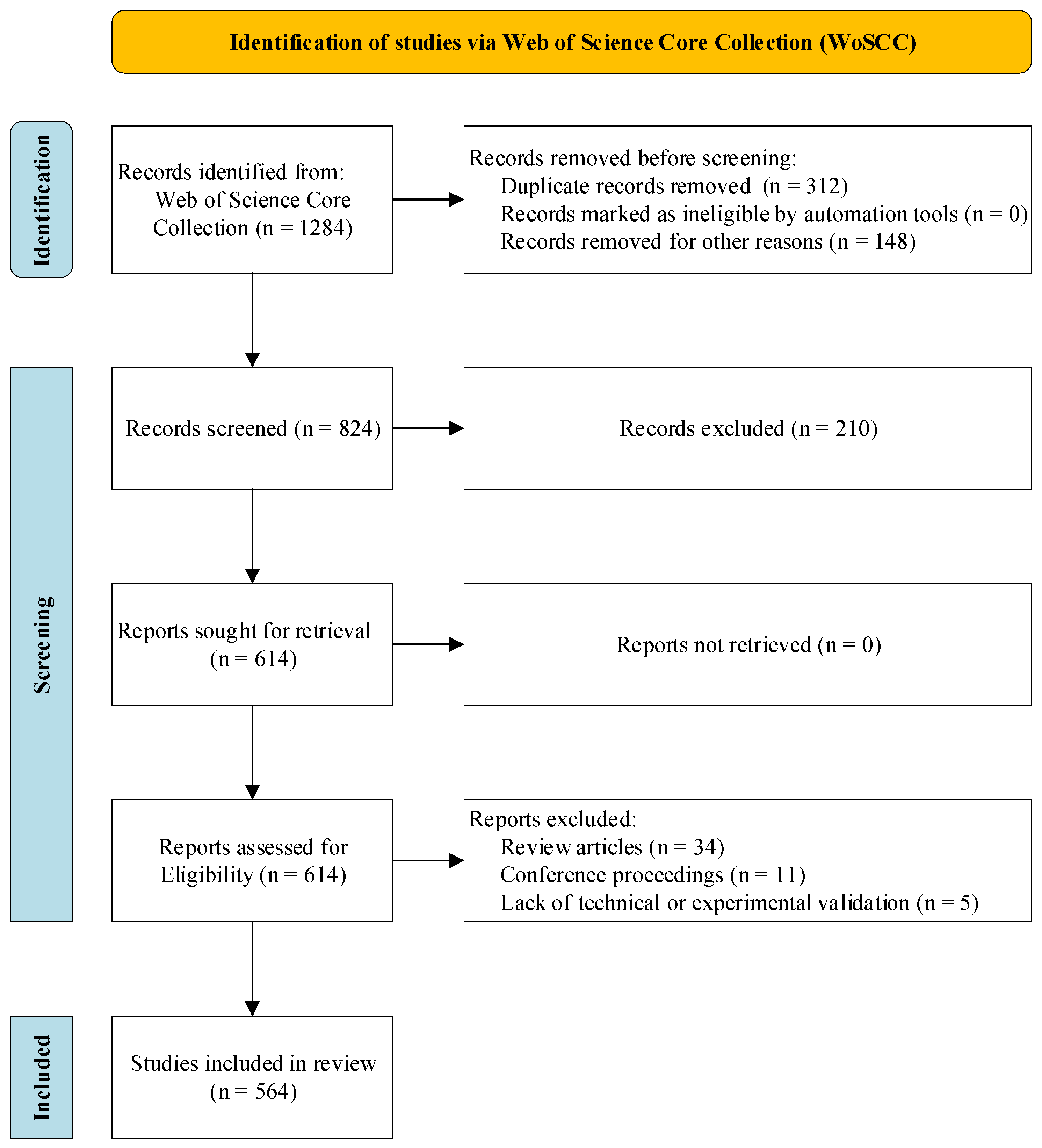

Review Methodology and Paper Selection (PRISMA)

2. Target Recognition and Localization Technology

2.1. Traditional Recognition Methods

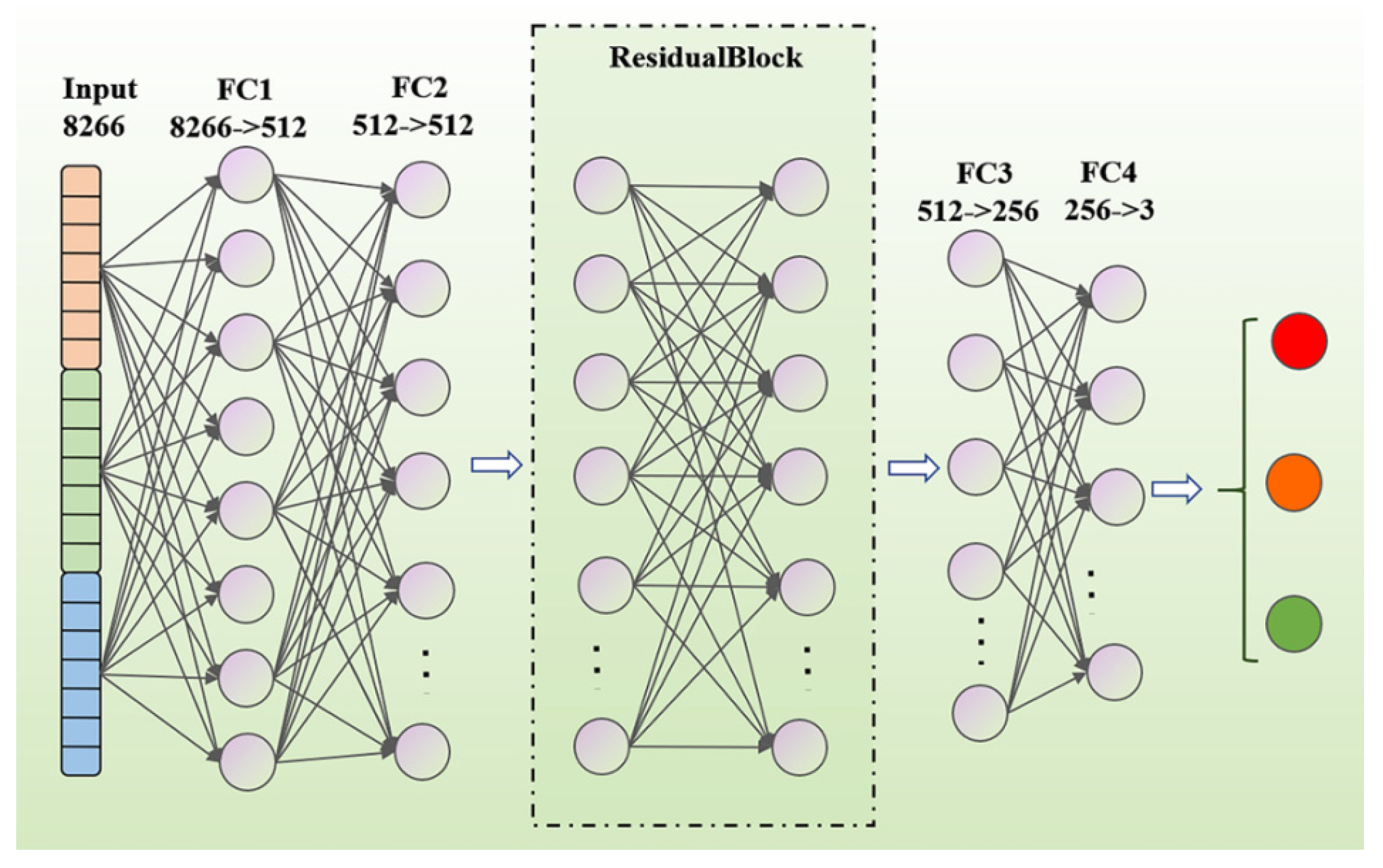

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Recognition Methods

2.2.1. Two-Stage Detection Algorithms

2.2.2. One-Stage Detection Algorithms

2.2.3. Pixel-Level Image Segmentation Techniques

2.3. Current Challenges in Recognition Technology

3. Motion Planning and Obstacle Avoidance Technology

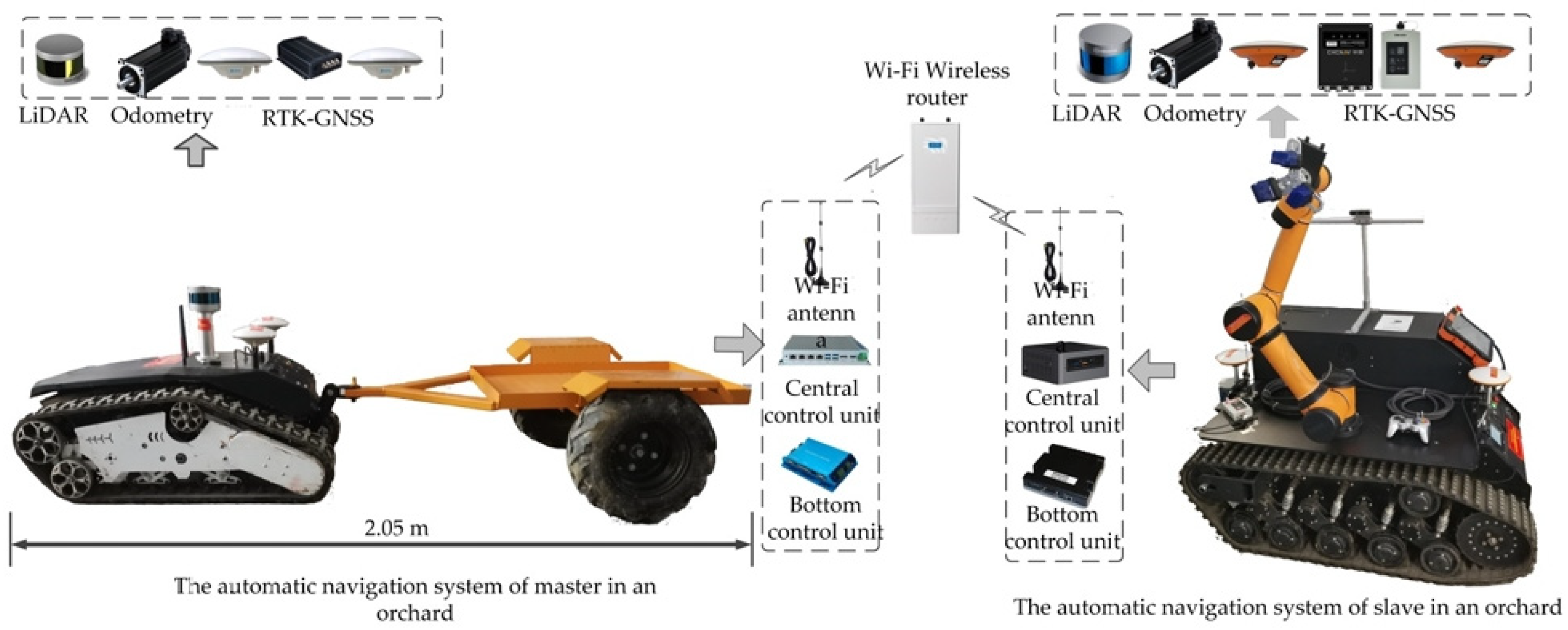

3.1. Orchard Path Navigation Technology

3.1.1. Path Navigation Using Traditional Algorithms

3.1.2. Path Navigation Using Intelligent Algorithms

3.1.3. Summary of Path-Planning Technologies

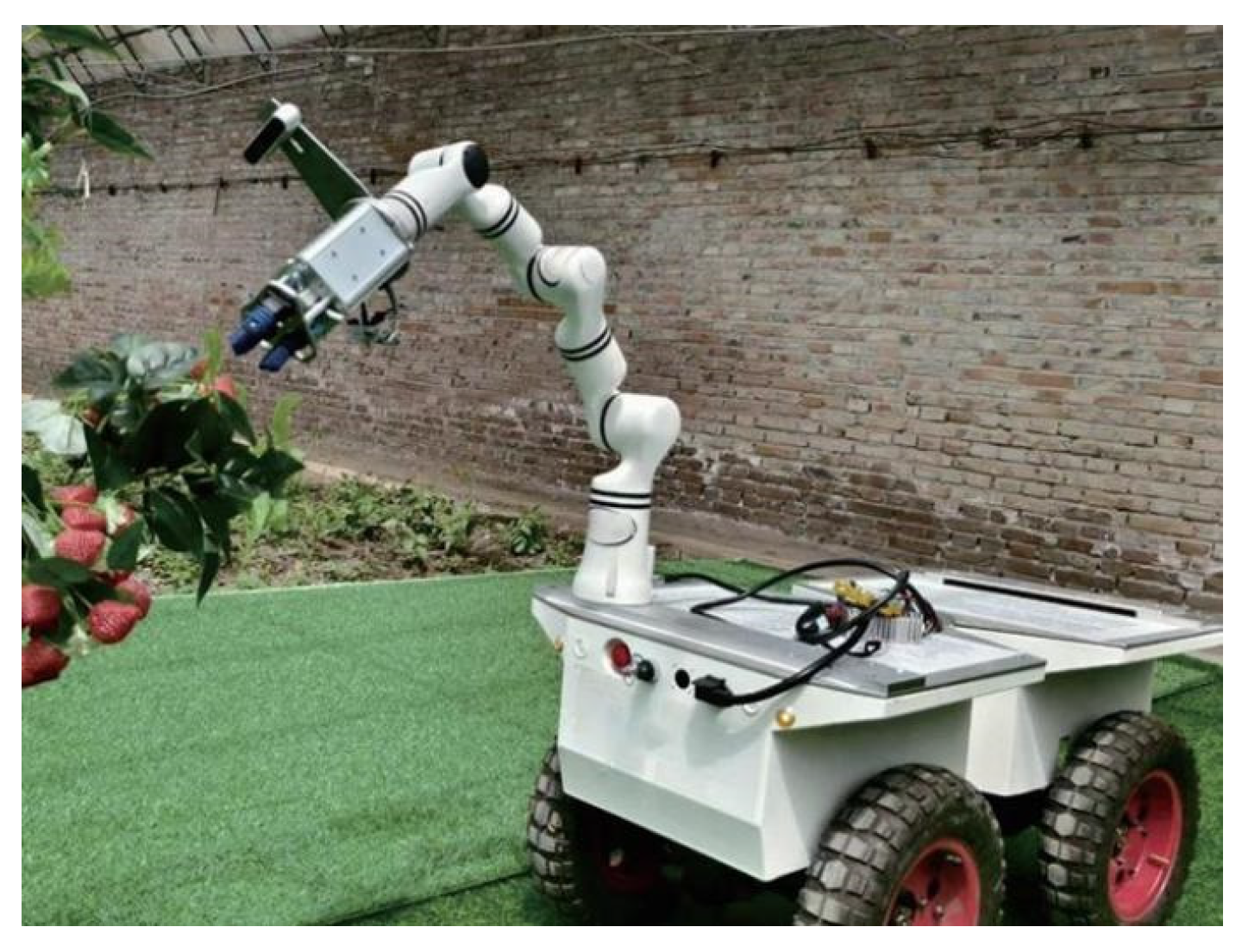

3.2. Manipulator Harvesting Planning

3.3. Current Challenges in Motion Planning Technology

4. Harvesting Device Mechanism and Optimization

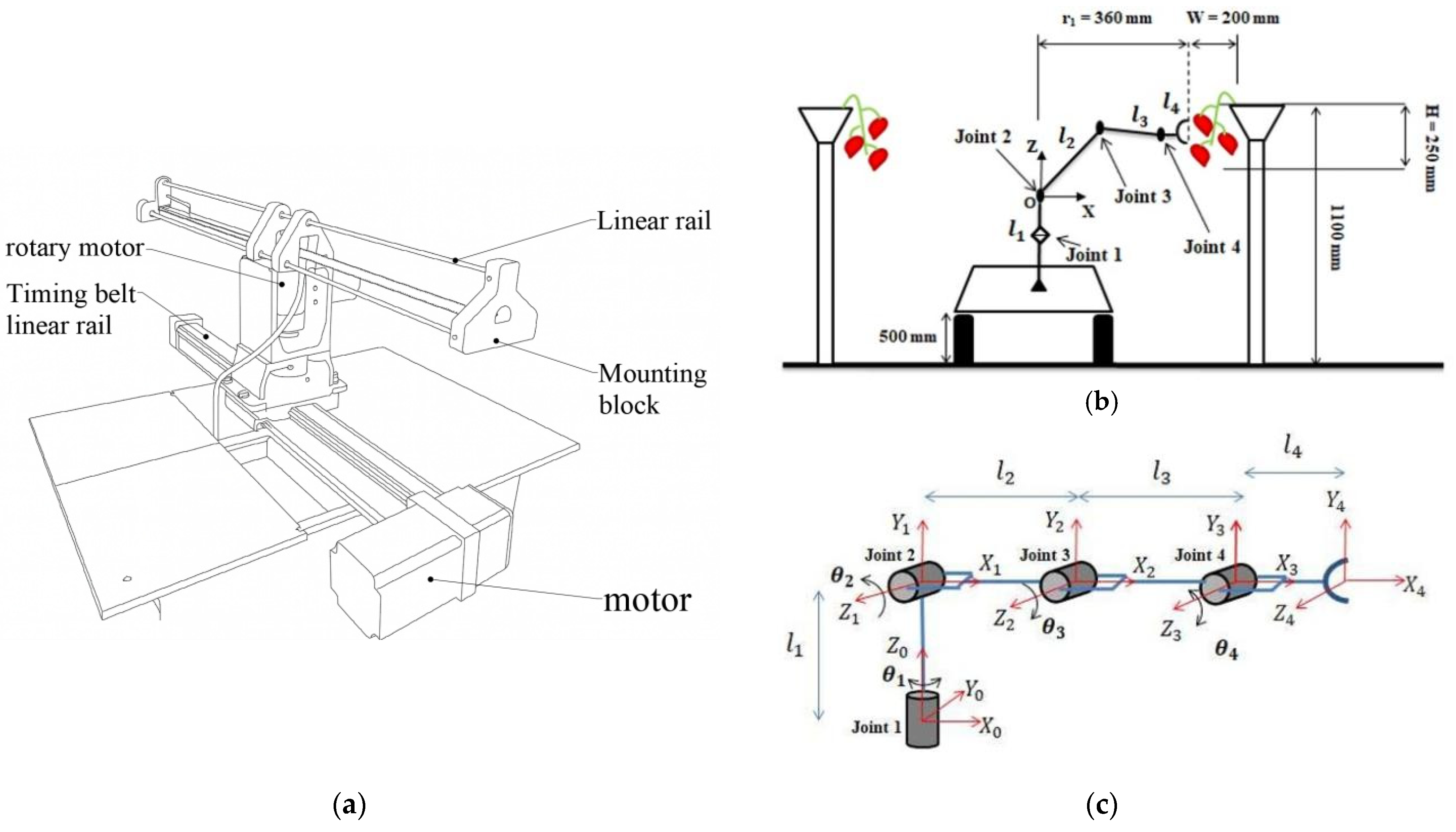

4.1. Manipulator Design and Optimization

4.1.1. Optimization of Degree-of-Freedom Configuration

4.1.2. Dual-Arm Cooperative Control

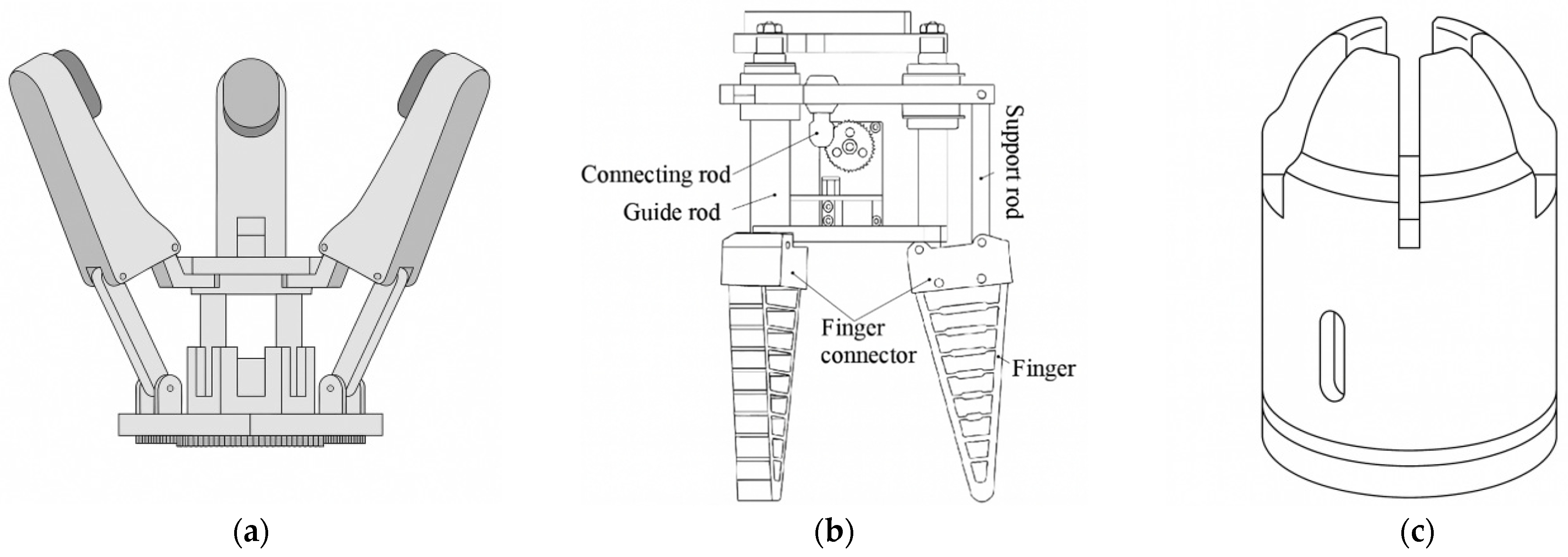

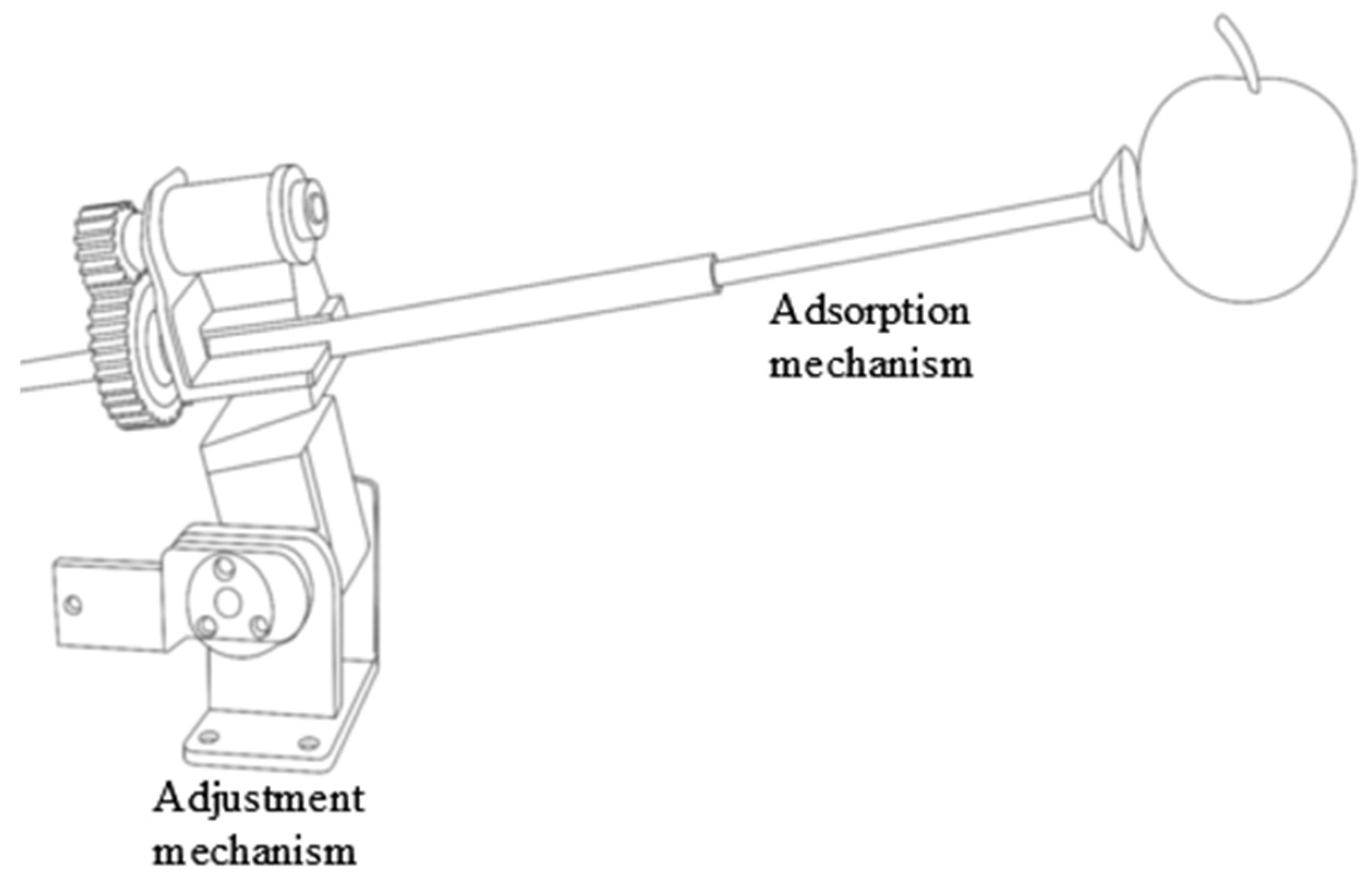

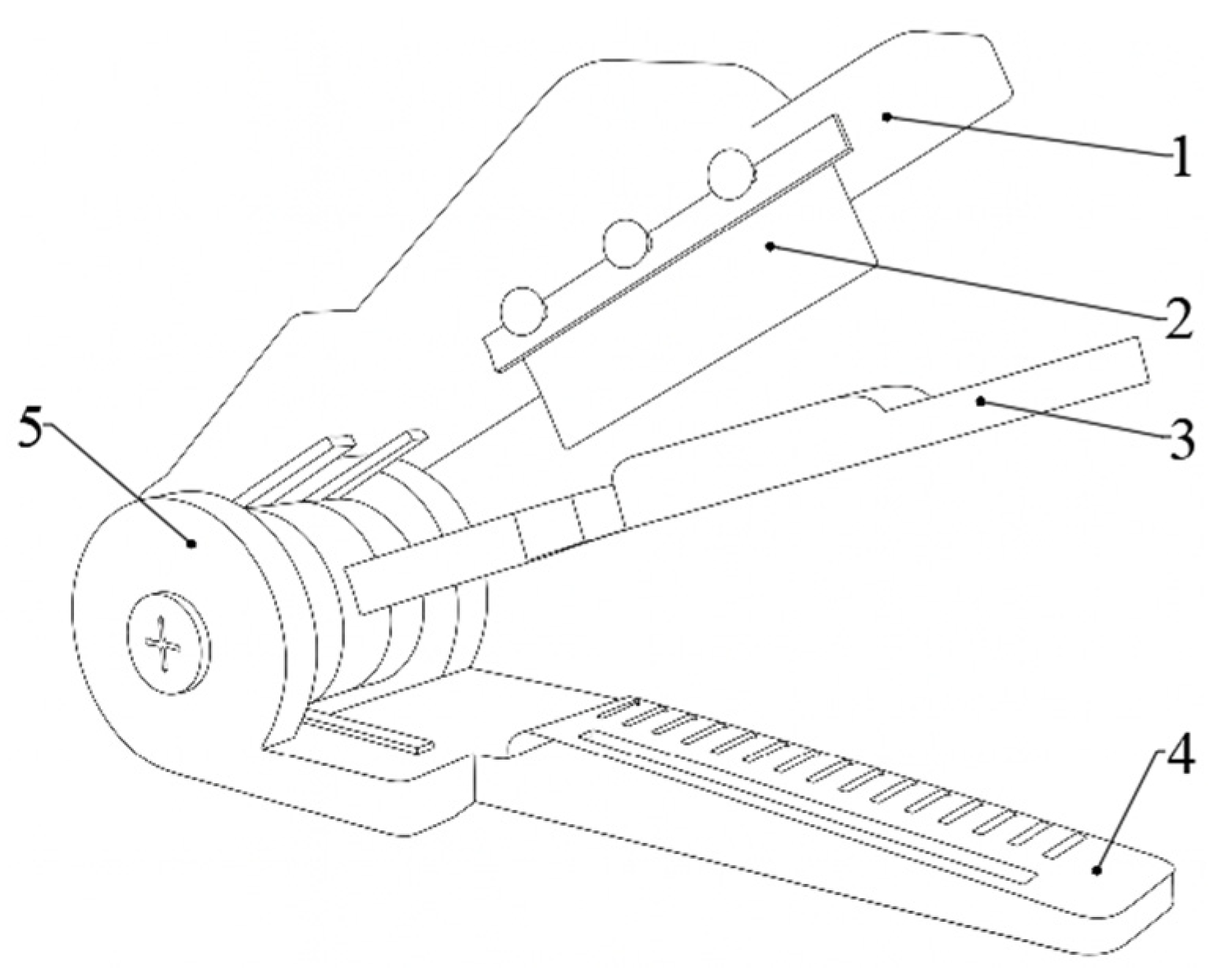

4.2. End-Effector Design and Optimization

5. System Integration and Optimization

5.1. Multi-Sensor Fusion Technologies

5.2. Hierarchical Control System Architecture

5.2.1. Distributed Architecture

5.2.2. Edge–Cloud Collaborative Computing

5.3. System-Level Integration Challenges and Trade-Offs

6. Field Deployment Status and System-Level Application Analysis

6.1. Representative International Systems and Deployment Characteristics

6.2. Representative China Systems and Application Constraints

6.3. Cross-System Synthesis and Engineering Implications

7. Technological Development Trends and Analysis

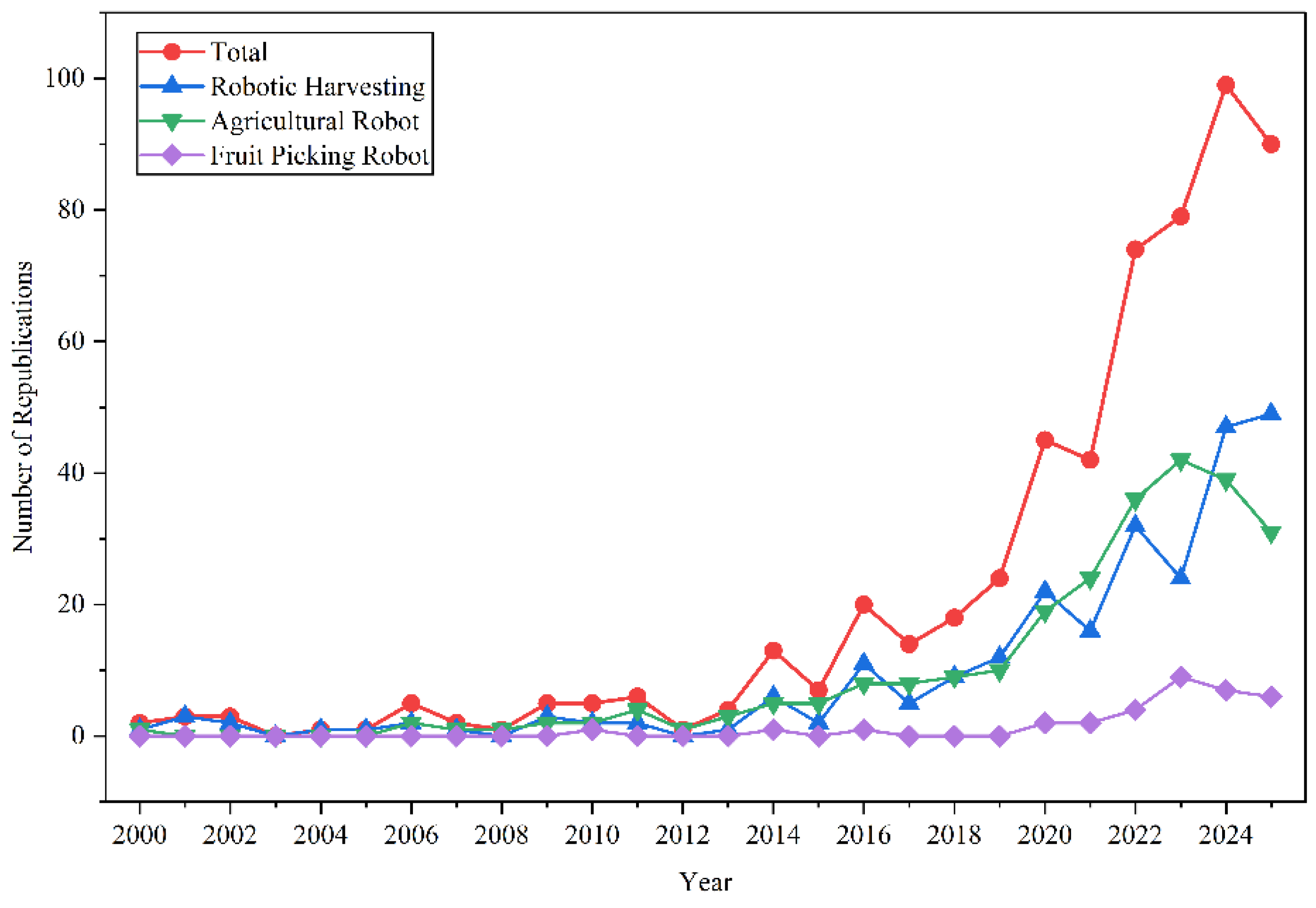

7.1. Publication Trend Analysis

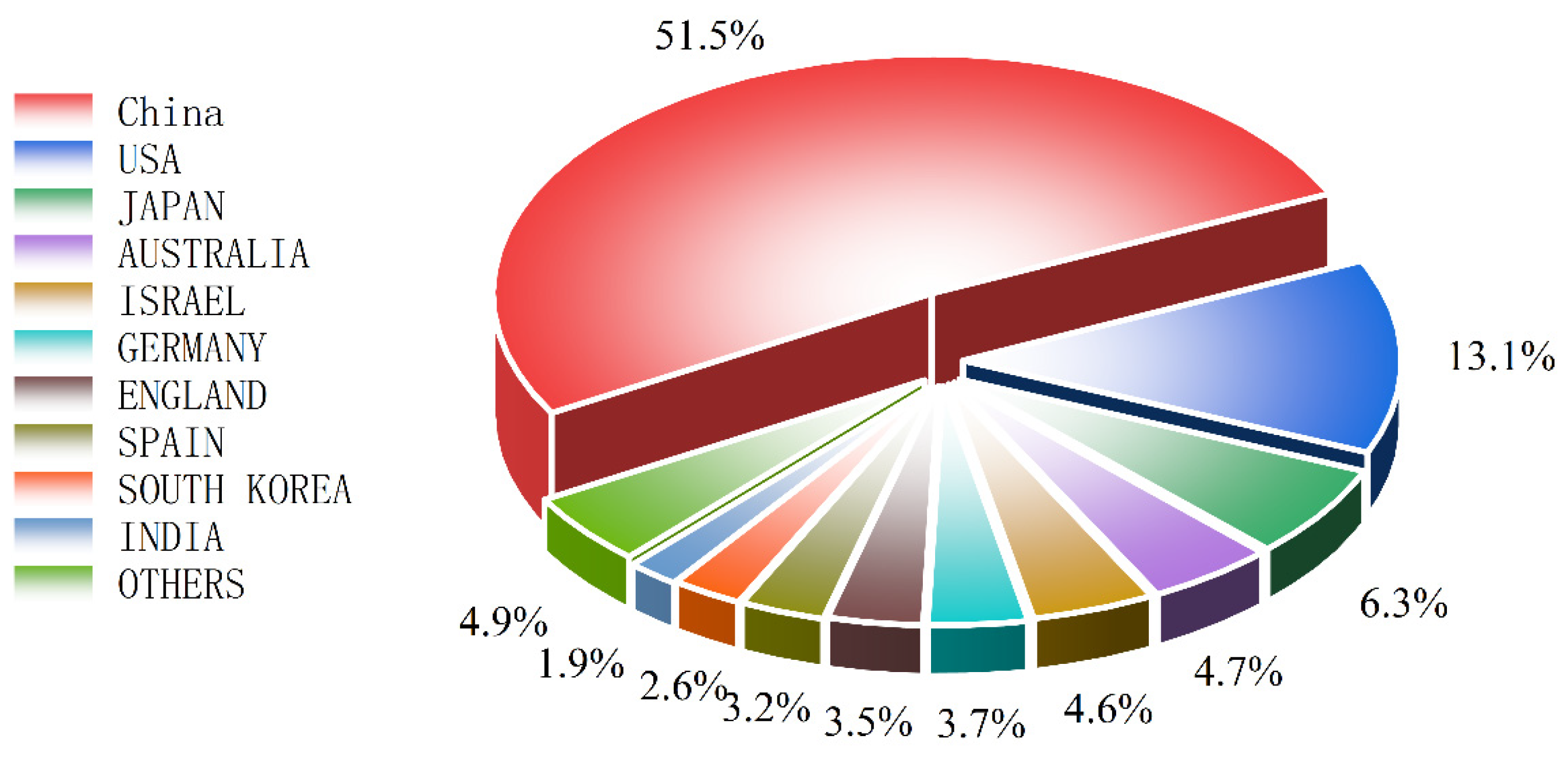

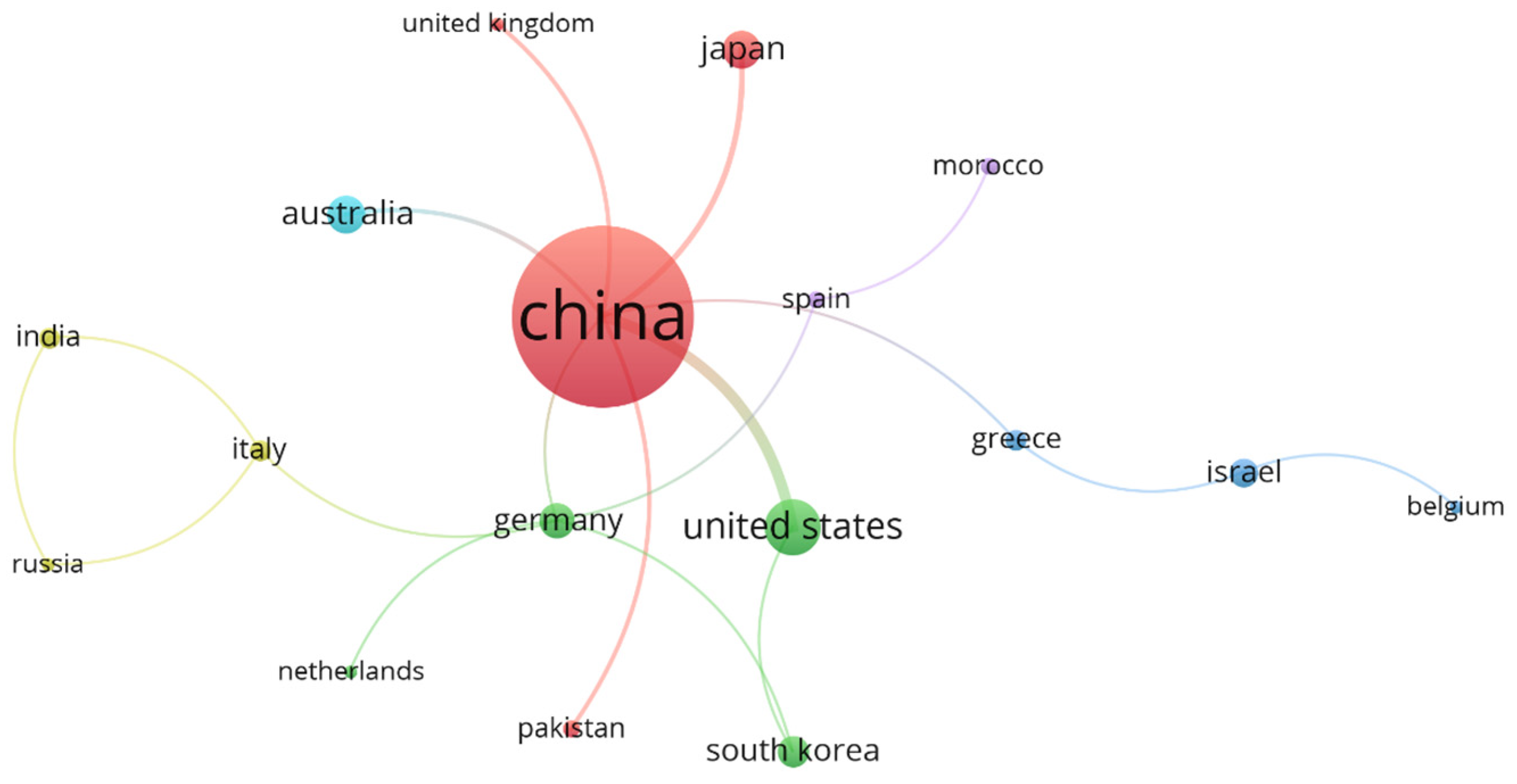

7.2. Analysis of Publication Distribution by Region

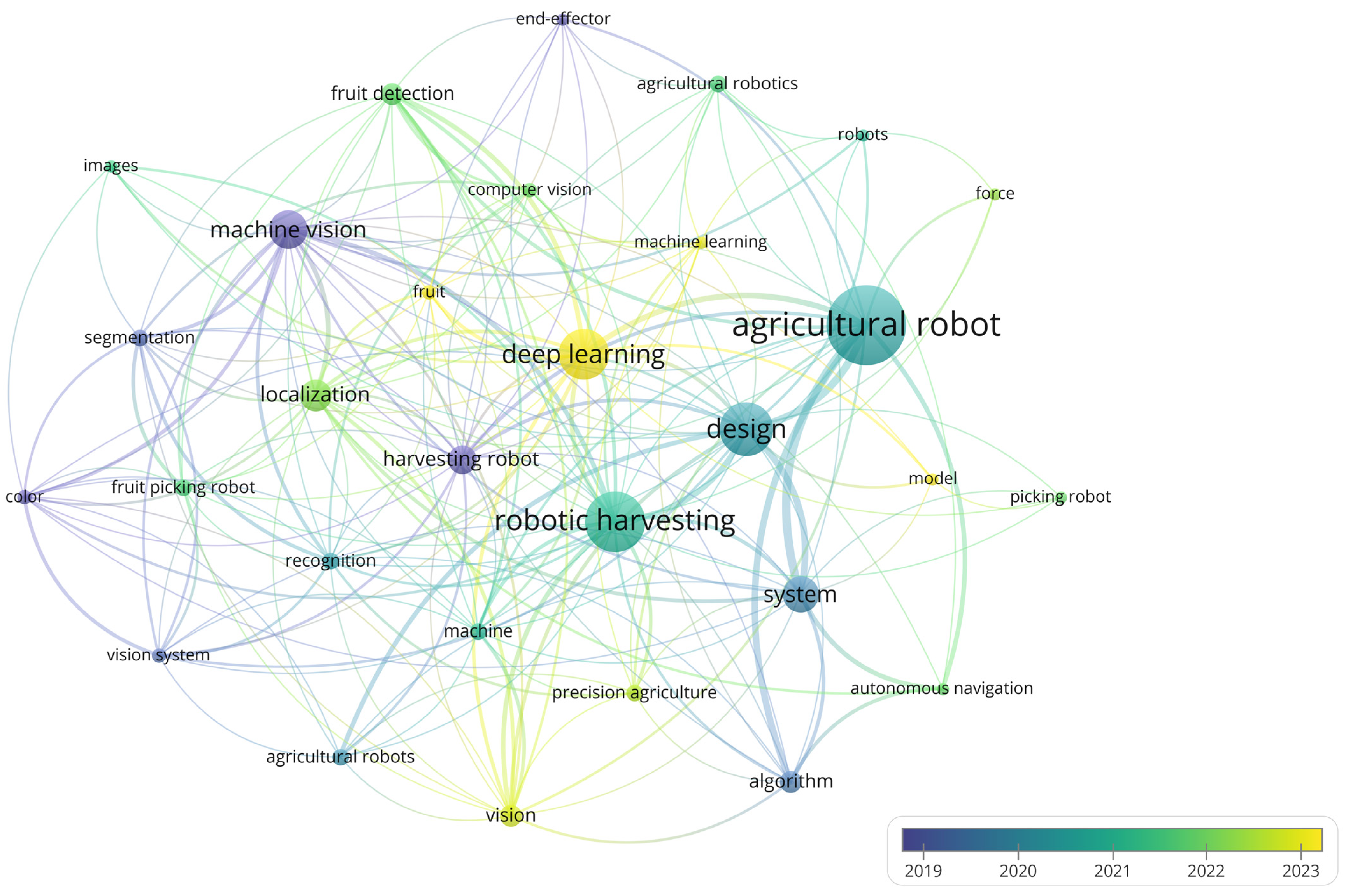

7.3. Keyword Hotspot Analysis

8. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Kang, N.; Qu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, H. Automatic fruit picking technology: A comprehensive review of research advances. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Luo, L.; Li, J.; Lian, G.; Zou, X. Recognition and Localization Methods for Vision-Based Fruit Picking Robots: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Ding, X.; Yuan, J.; Xu, W.; Liu, J. Optimization Study on the Freshwater Production Ratio from the Freezing and Thawing Process of Saline Water with Varied Qualities. Agronomy 2024, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, K.; Sun, Y.; Lei, X.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lv, X. An autonomous navigation method for orchard mobile robots based on octree 3D point cloud optimization. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1510683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Jiang, S. Vision-based fruit recognition via multi-scale attention CNN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 210, 107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y. A Review of Research on Fruit and Vegetable Picking Robots Based on Deep Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, B. Outstanding in the Field: Robots That Can Pick Fruit. Available online: https://control.com/industry-articles/outstanding-in-the-field-robots-that-can-pick-fruit/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Kootstra, G.; Wang, X.; Blok, P.M.; Hemming, J.; van Henten, E. Selective Harvesting Robotics: Current Research, Trends, and Future Directions. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2021, 2, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Onishi, Y.; Kawahara, T.; Fukao, T. Automated harvesting by a dual-arm fruit harvesting robot. ROBOMECH J. 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Duke, M.; Au, C.K.; Lim, S.H. Work distribution of multiple Cartesian robot arms for kiwifruit harvesting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169, 105202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lammers, K.; Chu, P.; Li, Z.; Lu, R. System design and control of an apple harvesting robot. Mechatronics 2021, 79, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Next Move Strategy Consulting. China Agriculture Robots Market: By Type (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Milking Robots, Driverless Tractors, Automated Harvest Robots, Others), by Farming Type, by Application—Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast 2023–2030; AG630; Next Move Strategy Consulting: Pune, India, 2025; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China; National Development and Reform Commission; Ministry of Science and Technology; Ministry of Public Security; Ministry of Civil Affairs; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; National Health Commission; Ministry of Emergency Management; People’s Bank of China; et al. The 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Robotics Industry (Gongxinbu Lianguī [2021] No. 206); 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-12/28/content_5664988.htm (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. New Round of Agricultural Machinery Purchase Subsidy Policy Released; NDRC: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Au, W.; Kang, H.; Chen, C. Intelligent robots for fruit harvesting: Recent developments and future challenges. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1856–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, A.; Hussain, S.; Aqib, M.; Cheema, M.J.M.; Saleem, S.R.; Farooq, U. Development Challenges of Fruit-Harvesting Robotic Arms: A Critical Review. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 2216–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Lei, X.; Yuan, Q.; Qi, Y.; Ma, Z.; Qian, S.; Lyu, X. Key Technologies for Autonomous Fruit- and Vegetable-Picking Robots: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, G.; Chen, X. Advances in Semi-Supervised Learning Methods for Plant Image Processing. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2025, 61, 45–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Shi, G.; Liu, X. Optimization of Rotten Apple Image Segmentation Using a Spatial Feature Clustering Algorithm. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 159–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, Z. Flower Image Segmentation Based on an Improved OTSU Algorithm Using the HSV Color Model. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2019, 40, 155–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Pu, L.; Song, H. Using an improved lightweight YOLOv8 model for real-time detection of multi-stage apple fruit in complex orchard environments. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 11, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathi, S.; Tamil Selvi, S. Detection of maturity stages of coconuts in complex background using Faster R-CNN model. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 202, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Rao, H.; Wang, Y. Detection of Camellia oleifera Fruits in Natural Scenes Based on Faster R-CNN. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2021, 33, 67–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, H. Detection of Laiyang Pear Targets Based on the Mask R-CNN Model. J. Qingdao Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 37, 301–305. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Siricharoen, P.; Yomsatieankul, W.; Bunsri, T. Fruit maturity grading framework for small dataset using single image multi-object sampling and Mask R-CNN. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ma, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H. Apple Detection in Complex Scene Using the Improved YOLOv4 Model. Agronomy 2021, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Karkee, M. Canopy-attention-YOLOv4-based immature/mature apple fruit detection on dense-foliage tree architectures for early crop load estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Tang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Z.; Huang, P.; Liu, B.; Yang, N.; et al. Real-time and accurate detection of citrus in complex scenes based on HPL-YOLOv4. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, C.; Ji, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T. D3-YOLOv10: Improved YOLOv10-Based Lightweight Tomato Detection Algorithm Under Facility Scenario. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Shao, G.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, T. CR-YOLOv9: Improved YOLOv9 Multi-Stage Strawberry Fruit Maturity Detection Application Integrated with CRNET. Foods 2024, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Song, H. AHG-YOLO: Multi-category detection for occluded pear fruits in complex orchard scenes. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1580325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Maleva, T.; Soloviev, V. Using YOLOv3 Algorithm with Pre- and Post-Processing for Apple Detection in Fruit-Harvesting Robot. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, M.O. Tomato detection based on modified YOLOv3 framework. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Duong, T.P.; Phan, Q.H.; Lien, C.H. Tomato Fruit Detection Using Modified Yolov5m Model with Convolutional Neural Networks. Plants 2023, 12, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Chang, P.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Jia, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhong, H.; Liu, S. CES-YOLOv8: Strawberry Maturity Detection Based on the Improved YOLOv8. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, R.; Liu, Y.; Xu, G. TL-YOLOv8: A Blueberry Fruit Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8 and Transfer Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 86378–86390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, Y. Detection of Fruit using YOLOv8-based Single Stage Detectors. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. IJACSA 2023, 14, 0141208. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, G.; Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Dai, Z. Multi-stage tomato fruit recognition method based on improved YOLOv8. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1447263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Qian, T.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, J. An Enhanced YOLOv5 Model for Greenhouse Cucumber Fruit Recognition Based on Color Space Features. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, Y. Object Detection Algorithm for Citrus Fruits Based on Improved YOLOv5 Model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hou, Y.; Cui, T.; Li, H.; Shangguan, F.; Cao, L. YOLOv8-CML: A lightweight target detection method for color-changing melon ripening in intelligent agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Feng, Q.; Han, L. Lightweight Apple Instance Segmentation Method SSWYOLOv11n for Complex Orchard Environments. Smart Agric. 2025, 7, 114–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, P.; Raja, P.; Karkee, M.; Raja, M.; Baig, R.U.; Trung, K.T.; Hoang, V.T. Performance analysis of modified DeepLabv3+ architecture for fruit detection and localization in apple orchards. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Li, C.; Jiang, H.; Takeda, F. Deep learning image segmentation and extraction of blueberry fruit traits associated with harvestability and yield. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Yan, W.Q.; Li, Y. Lightweight and efficient deep learning models for fruit detection in orchards. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, N.; Niu, Y.; Yin, X.; Ding, Y.; Ge, X. Accurate segmentation of green fruit based on optimized mask RCNN application in complex orchard. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 955256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Barrios, J.D.; Escobedo Cabello, J.A.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Montoya-Cavero, L.-E. Green Sweet Pepper Fruit and Peduncle Detection Using Mask R-CNN in Greenhouses. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dong, G.; Fan, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, H. Fruit Stalk Recognition and Picking Point Localization of New Plums Based on Improved DeepLabv3+. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, S. Realizing the Potential of Eastern Uganda’s Smallholder Dairy Sector through Participatory Evaluation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, T.; Cao, H. Development of an Optimized YOLO-PP-Based Cherry Tomato Detection System for Autonomous Precision Harvesting. Processes 2025, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez del Pozo, D.; Martín-Gómez, J.J.; Reyes Tomala, N.I.; Tocino, Á.; Cervantes, E. Seed Geometry in Species of the Nepetoideae (Lamiaceae). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, R. Picking-Point Localization Algorithm for Citrus Fruits Based on Improved YOLOv8 Model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, C.; Ma, Y.; Liu, C.; Ru, M.; Sun, J.; Zhao, C. Peduncle collision-free grasping based on deep reinforcement learning for tomato harvesting robot. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wen, M.; Zeng, Z.; Tian, Y. Cherry Tomato Bunch and Picking Point Detection for Robotic Harvesting Using an RGB-D Sensor and a StarBL-YOLO Network. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, D.; Li, Z. Advances in Deep-Learning-Based Spherical Fruit Harvesting and Recognition Algorithms. J. Fruit. Sci. 2025, 42, 412–426. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, C.; Huang, R.; Tong, K.; He, Y.; Xu, L. Path planning for mobile robots in greenhouse orchards based on improved A* and fuzzy DWA algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Li, J.; Li, P. Improving path planning for mobile robots in complex orchard environments: The continuous bidirectional Quick-RRT* algorithm. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1337638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammrei, S.; Boubaker, S.; Kolsi, L. Improved Dijkstra Algorithm for Mobile Robot Path Planning and Obstacle Avoidance. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 5939–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Fu, L.H.; Pei, Y.H.; Lan, C.Y.; Hou, H.Y.; Song, H. Three-dimensional continuous picking path planning based on ant colony optimization algorithm. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Mo, Z.; Ma, C.; Xiao, J.; Jia, R.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Design and validation of a multi-objective waypoint planning algorithm for UAV spraying in orchards based on improved ant colony algorithm. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Path Planning of Fruit and Vegetable Picking Robots Based on Improved a* Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. INMATEH Agric. Eng. 2023, 71, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, R.; Lyu, M.; Zhang, J. Transformer-Based Reinforcement Learning for Multi-Robot Autonomous Exploration. Sensors 2024, 24, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhai, C.; Zou, W.; Song, J.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Advances in Autonomous Navigation Technology for Intelligent Orchard Operation Equipment. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2024, 55, 1–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, S.; Jiang, Q. Apple-Picking Robot Picking Path Planning Algorithm Based on Improved PSO. Electronics 2023, 12, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Yan, H.; Huang, Z.; Ai, S.; Xu, Y.; Fu, R.; Zou, X. A Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization for Trajectory Planning of Fruit Picking Manipulator. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Zou, X.; Tang, Y. Collision-free path planning for a guava-harvesting robot based on recurrent deep reinforcement learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 188, 106350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ru, M.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, C. Fruit flexible collecting trajectory planning based on manual skill imitation for grape harvesting robot. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Kim, J.; Seol, J.; Son, H.I. A review on multirobot systems in agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xie, F.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Guo, X.; Feng, Q. A multi-arm robot system for efficient apple harvesting: Perception, task plan and control. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, C.; Guo, Z.; Yin, C.; Wu, X.; Lv, X.; Chen, Q. Research on 3D Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning for Apple Picking Robotic Arm. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Quan, J.; Yan, W. Three-Dimensional Obstacle Avoidance Harvesting Path Planning Method for Apple-Harvesting Robot Based on Improved Ant Colony Algorithm. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistri, F.; Pan, Y.; Bartels, J.; Behley, J.; Stachniss, C.; Lehnert, C. Improving Robotic Fruit Harvesting Within Cluttered Environments Through 3D Shape Completion. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 7357–7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. Real-time guava tree-part segmentation using fully convolutional network with channel and spatial attention. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 991487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Yu, Q.; Deng, G.; Wu, T.; Zheng, D.; Lin, G.; Zhu, L.; Huang, P. A Fast and Accurate Obstacle Segmentation Network for Guava-Harvesting Robot via Exploiting Multi-Level Features. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Chen, C.; Chen, J.; Sun, L.; Sugirbay, A.; Chen, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, S.; Bu, L. Simplified 4-DOF manipulator for rapid robotic apple harvesting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, I.; Jaafari, H.I.; Chahboun, A.; Raissouni, N.; Achhab, N.B.; Azyat, A. Design optimization and trajectory planning of a strawberry harvesting manipulator. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2024, 13, 3948–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Feng, Q.; Guo, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L. Structural Parameter Optimization of a Tomato Robotic Harvesting Arm: Considering Collision-Free Operation Requirements. Plants 2024, 13, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Guo, S.; Chen, A.; Cheng, R.; Cui, X. Design and experimentation of multi-fruit envelope-cutting kiwifruit picking robot. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1338050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ding, X.; Li, K.; Cui, Y. Double-Arm Cooperation and Implementing for Harvesting Kiwifruit. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Peng, Y.; Shan, H. Development of a dual-arm rapid grape-harvesting robot for horizontal trellis cultivation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 881904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, T. Dual-arm cooperation and implementing for robotic harvesting tomato using binocular vision. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 114, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lv, M.; Xu, Q.; Xu, R. Design and Analysis of a Robotic Gripper Mechanism for Fruit Picking. Actuators 2024, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, T.; Yan, T.; Xie, F.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, C. A Soft Gripper Design for Apple Harvesting with Force Feedback and Fruit Slip Detection. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, E.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Dworak, V.; Weltzien, C.; Fernandez, R. Soft gripper for small fruits harvesting and pick and place operations. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 10, 1330496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, M.; Igathinathane, C.; Vougioukas, S.; Saha, C.K.; Mustafa, N.S.; Salama, D.S.; et al. Vacuum suction end-effector development for robotic harvesters of fresh market apples. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 249, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, X.; Yang, Z. Design, simulation, and experiment for the end effector of a spherical fruit picking robot. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2023, 20, 17298806231213442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Jian, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhong, X. Kinematic design of new robot end-effectors for harvesting using deployable scissor mechanisms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 222, 109039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Seol, J.; Pak, J.; Jo, Y.; Jun, J.; Son, H.I. A novel end-effector for a fruit and vegetable harvesting robot: Mechanism and field experiment. Precis. Agric. 2022, 24, 948–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, Z.; You, W.; Lin, J.; Tang, X.; Huang, H. An Autonomous Fruit and Vegetable Harvester with a Low-Cost Gripper Using a 3D Sensor. Sensors 2019, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, H.; Zhou, H.; Au, W.; Wang, M.Y.; Chen, C. Development and evaluation of a robust soft robotic gripper for apple harvesting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, C. Accurate fruit localisation using high resolution LiDAR-camera fusion and instance segmentation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 203, 107450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Kang, H.; Chen, C. ORB-Livox: A real-time dynamic system for fruit detection and localization. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gené-Mola, J.; Gregorio, E.; Guevara, J.; Auat, F.; Sanz-Cortiella, R.; Escolà, A.; Llorens, J.; Morros, J.-R.; Ruiz-Hidalgo, J.; Vilaplana, V.; et al. Fruit detection in an apple orchard using a mobile terrestrial laser scanner. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 187, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyrathna, R.; Nakaguchi, V.M.; Liu, Z.; Sampurno, R.M.; Ahamed, T. 3D Camera and Single-Point Laser Sensor Integration for Apple Localization in Spindle-Type Orchard Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Lee, W.S.; Alchanatis, V.; Ehsani, R.; Schueller, J.K. Immature green citrus fruit detection using color and thermal images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 152, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, C.; Yoon, S.C.; Ni, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Guo, X. Development of Multimodal Fusion Technology for Tomato Maturity Assessment. Sensors 2024, 24, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukab, S.; Komal; Ghodki, B.M.; Ray, H.; Kalnar, Y.B.; Narsaiah, K.; Brar, J.S. Improving real-time apple fruit detection: Multi-modal data and depth fusion with non-targeted background removal. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Deka, B. Deep Learning-Based Selective Feature Fusion for Litchi Fruit Detection Using Multimodal UAV Sensor Measurements. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 6, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, M.; Cheng, Q.; Liang, G.; Fan, F. A novel hand-eye calibration method of picking robot based on TOF camera. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1099033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Qi, P.; Han, L.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, X. Navigation system for orchard spraying robot based on 3D LiDAR SLAM with NDT_ICP point cloud registration. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Liu, H.; Hao, W.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z. Development of a Combined Orchard Harvesting Robot Navigation System. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Yao, H.; Du, M.; Ji, P.; Si, X. Distributed Averaging Problems of Agriculture Picking Multi-Robot Systems via Sampled Control. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 898183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, R.R.; Navas, E.; Dworak, V.; Auat Cheein, F.A.; Weltzien, C. A modular sensing system with CANBUS communication for assisted navigation of an agricultural mobile robot. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 223, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahidi, U.A.; Khan, A.; Zhivkov, T.; Dichtl, J.; Li, D.; Parsa, S.; Hanheide, M.; Cielniak, G.; Sklar, E.I.; Pearson, S.; et al. Optimising robotic operation speed with edge computing over 5G networks: Insights from selective harvesting robots. J. Field Robot. 2024, 41, 2771–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Mafra, S.; Teixeira, E.; Figueiredo, F. Smart Strawberry Farming Using Edge Computing and IoT. Sensors 2022, 22, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Li, T.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, H.; Chen, L.; Zhao, C. Boosting Cost-Efficiency in Robotics: A Distributed Computing Approach for Harvesting Robots. J. Field Robot. 2024, 42, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Kent’s growers given lesson in robotic fruit picking from Dogtooth Technologies near Cambridge. Kent. Online 2024. Available online: https://www.kentonline.co.uk/kent/news/the-robots-that-could-help-kent-s-fruit-picking-problems-312244. (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Mooney, M. Robotic Picker Deployed at Kent Fruit Farm. Available online: https://www.roboticsandautomationmagazine.co.uk/news/agriculture/robotic-picker-deployed-at-kent-fruit-farm.html (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Dogtooth Technologies. Robotic Strawberry Harvesting on Your Farm: Gen-5 Robot Specification Sheet (Version 0.1)). Dogtooth Technologies, 2025. Available online: https://dogtooth.tech/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Gen-5-Specification-Sheet-0.1.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Agrobot. E-Series Robotic Harvesters for Strawberry Picking. Agrobot. Available online: https://www.agrobot.com/e-series (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Ripe Robotics. Meet Eve: Our Commercial Prototype. Ripe Robotics. Available online: https://www.riperobotics.com/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Tevel Aerobotics Technologies. Technology: Flying Autonomous Robots™ for Tree Fruit Harvesting. Tevel Aerobotics Technologies. Available online: https://www.tevel-tech.com/technology/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- EasySmart (ZWinSoft). Product Introduction of EasySmart Fruit-Picking Robot. EasySmart. Available online: https://ep.zwinsoft.com/%E6%99%BA%E6%98%93%E6%97%B6%E4%BB%A3%E6%B0%B4%E6%9E%9C%E9%87%87%E6%91%98%E6%9C%BA%E5%99%A8%E4%BA%BA/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

| Target Fruit | Baseline Algorithm | Improvement Points | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | YOLOv8n | ShuffleNetV2 + Ghost backbone + WIoU loss + SE module | Accuracy 94.1%, mAP 91.4%; only 2.6 MB | [22] |

| Apple | YOLOv3 | Preprocessing module; boundary equalization; activation enhancement | Recall 90.8%, detection speed 19 ms | [34] |

| Tomato | YOLOv3 | DenseNet feature fusion + SPP spatial pyramid + Mish activation | AP 95.0%, detection speed 52 ms | [35] |

| Cherry/Tomato | YOLOv5m | BoTNet backbone + Transformer-MHSA multi-head self-attention | mAP 94%, TPR 94–96% | [36] |

| Strawberries | YOLOv8 | ConvNeXt-V2 backbone + ECA attention + SIoU loss | Accuracy 82.4% (+8.4%), mAP 92.8% | [37] |

| Blueberries | YOLOv8 | MPCA multi-perspective attention + OREPA parameter optimization | Solved small-fruit overlap problem | [38] |

| Multiple Fruit Types | YOLOv8l | Multi-fruit mixed dataset + CSP module + C2f structure | recall 96% | [39] |

| Tomato | YOLOv8n | EfficientViT backbone + C2f-Faster + SIoU + Auxiliary Head | mAP 93.9%, accuracy 91.6% | [40] |

| Cucumber | YOLOv5s | Cr-color channel training + ReliefF feature weighting | mAP 85.2% | [41] |

| Citrus | YOLOv5 | RFCF perceptual weighting + FLA hierarchical attention + K-means + feature enhancement | mAP + 0.6%, detection speed 1.26 ms/frame | [42] |

| Cantaloupe | YOLOv8n | PCConv partial convolution + EMA multi-scale attention + IoU + IoU weighting | mAP + 1.4%, FPS + 42.9% | [43] |

| Target | Research Task | Algorithm Model | Innovation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pepper | Fruit–peduncle joint detection | Mask R-CNN | Achieves high-precision extraction of fruit–peduncle regions through multi-scale feature fusion, particularly under complex illumination | [49] |

| Pear | Fruit recognition and peduncle localization | DeepLabv3+ | Uses MobileNet-based lightweight backbone and attention mechanisms to achieve accurate peduncle segmentation and recognition | [50] |

| Tomato | Cutting-point detection | YOLOv8n-DDA-SAM + DOPE | Combines 3D geometric constraints with image features to enable autonomous cutting-point detection | [51] |

| Loquat | Peduncle detection | YOLO-PP (lightweight variant) | Incorporates transformer modules to enhance fine-grained peduncle feature extraction, enabling accurate picking-point localization | [52] |

| Tomato | Ripeness + peduncle joint detection | YOLO-TMPPD | Integrates ripeness estimation with peduncle localization, improving multi-task perception capability | [53] |

| Citrus | Picking-point localization | Two-Stage CPPL algorithm | Achieves accurate peduncle localization by decoupling segmentation and regression tasks | [54] |

| Tomato | Fruit–peduncle joint detection + robustness optimization | Vision-based deep-learning framework | Enhances robustness of robotic picking in complex orchards through spatial structural constraints | [55] |

| Cherry Tomato | Multi-view peduncle detection | StarBL-YOLO + RGB-D | Utilizes RGB-D fusion for improved peduncle detection accuracy and robust picking-point estimation | [56] |

| Baseline Algorithm | Improvement Strategy | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A* | Introduction of environmental constraints; removal of redundant nodes | constraints; removal of redundant nodes; increased global planning efficiency | [58] |

| Dijkstra | Cluster fusion + adaptive optimization | Reduced path oscillation and improved smoothness | [60] |

| RRT | Double-tree expansion + heuristic optimization | Path length −8.5%; turning smoothness +21.7% | [59] |

| ACO | Enhanced pheromone updating; optimized search neighborhoods | Path length −6.2%; improved convergence stability | [61] |

| ACO | Multi-source pheromone optimization + angle-factor enhancement | Energy consumption −30%; flight time −46–59% | [62] |

| A*-PSO | Environmental constraint embedding + dual-strategy search | Path smoothness +6.9% | [63] |

| Evaluation Dimension | A* | Dijkstra | RRT | ACO | A*-PSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path optimality | 85% | 100% | 68% | 92% | 89% |

| Computation time (100 m) | 0.3 s | 2.1 s | 0.8 s | 5.2 s | 1.7 s |

| Memory usage | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High |

| Dynamic obstacle-avoidance ability | Weak | Weak | Strong | Medium | Medium |

| Parameter sensitivity | Low | Low | High | High | Medium |

| Multi-objective optimization | Not supported | Not supported | Not supported | Supported | Supported |

| Target | Research Task | Algorithm Model | Innovation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | Branch topology and 3D environment reconstruction | Improved Informed-RRT* + human posture estimation | Constructing branch topology; realizing dynamic 3D spatial constraint reconstruction | [72] |

| Apple | Dynamic obstacle detection and branch motion prediction | Improved swarm-intelligence algorithm + B-spline fitting | Fusion of posture features and complete branch geometry; enhanced prediction accuracy | [73] |

| Multi-fruit | Real-time 2D–3D flexible obstacle perception | Lightweight 3D neural networks | Dynamic segmentation of branches and leaves; improved environmental adaptability | [74] |

| Tomato | Branch vibration modeling and trajectory deviation recognition | Fully convolutional network (FCN) | Fine-grained extraction of branch–fruit topological relations | [75] |

| Tomato | Dry-branch occlusion prediction and collision-risk modeling | Multi-layer Informed-RRT* + OFN | Multi-scale feature extraction of leaf–branch structure; improved recognition of collision-risk regions | [76] |

| Type | Features | Representative Performance | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clamping | Three-finger gear-synchronous rotation with adaptive force control | Success rate 93%, damage < 5% | Complex structure, high manufacturing cost | [84] |

| Clamping | TPU soft material with slip-detection feedback | Success rate 80%, zero damage | Material ages easily, difficult to clean | [85] |

| Clamping | Can grasp fruits with different diameters; lightweight design | Success rate 87%, 5–10 s/fruit | Poor anti-interference ability; high air-pressure requirement | [86] |

| Clamping | Vacuum suction cup; rotary retraction separation with intelligent position adjustment | Success rate 81.7%, energy consumption −15% | Stability depends on surface smoothness | [87] |

| Cutting | Clustered rotary cutting tools for efficient cluster harvesting | Success rate 88%, cycle time 12 s | Applicable fruit shapes are limited | [80] |

| Cutting | Micro-motor-driven multi-edge blade, suitable for spherical fruit | Success rate 90%, damage < 8% | High control-precision requirement | [88] |

| Cutting | Modular design supporting simultaneous multi-fruit cutting | Success rate 85%, cycle time 10 s | Strong coupling in control, system is complex | [89] |

| Hybrid | Single-system control with short picking cycle | Picking cycle 15.5 s | System commissioning is complex | [90] |

| Hybrid | Three-plate co-driven, damage-prevention structure | Damage rate 3%, cycle time 8 s | Strong dependence on accurate pose recognition | [91] |

| Hybrid | Multi-modal perception for improved generality | Success rate 90%, damage < 6% | Control algorithm is complex | [92] |

| Type | Damage Rate (0.25) | Success Rate (0.3) | System Complexity (0.15) | Applicability (0.2) | Maintenance Cost (0.1) | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3.10 |

| Clamping | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.50 |

| Suction | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.95 |

| Cutting | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2.35 |

| Company | Target Crop | End-Effector | Metrics (Type) | Commercialization Info | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dogtooth Technologies | Strawberry (tabletop, greenhouse) | Integrated cutting, transfer, grading & packing | Throughput; extraction rate; waste rate; endurance | Gen-5 robots deployed on commercial farms | Structured cultivation & infrastructure dependent | [111] |

| Agrobot | Strawberry | Multi-arm stem grip-and-cut | Parallel harvesting capacity | Pre-commercial pilot systems | High mechanical & control complexity | [112] |

| Ripe Robotics | Apples, plums, peaches, nectarines | Vision-guided grasping/suction | Multi-fruit adaptability | Prototype systems tested in orchards | Strong dependence on orchard training systems | [113] |

| Tevel Aerobotics Technologies | Tree fruits (e.g., apples) | UAV-mounted suction picking | Fruit size range adaptability | Early-stage field demonstrations | Sensitive to wind & canopy occlusion | [114] |

| EasySmart | Strawberry (facility agriculture) | Bionic flexible finger gripper | Continuous operation capability | Product prototypes introduced | Metrics mainly promotional; limited field validation | [115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, T.; Sun, F.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Ying, J.; Wu, H.; Li, H. A Review of Key Technologies and Recent Advances in Intelligent Fruit-Picking Robots. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12020158

Lin T, Sun F, Li X, Guo X, Ying J, Wu H, Li H. A Review of Key Technologies and Recent Advances in Intelligent Fruit-Picking Robots. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(2):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12020158

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Tao, Fuchun Sun, Xiaoxiao Li, Xi Guo, Jing Ying, Haorong Wu, and Hanshen Li. 2026. "A Review of Key Technologies and Recent Advances in Intelligent Fruit-Picking Robots" Horticulturae 12, no. 2: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12020158

APA StyleLin, T., Sun, F., Li, X., Guo, X., Ying, J., Wu, H., & Li, H. (2026). A Review of Key Technologies and Recent Advances in Intelligent Fruit-Picking Robots. Horticulturae, 12(2), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12020158