Unraveling the Formation Mechanism of Wax Powder on Broccoli Curds: An Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic and Targeted Metabolomic Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis of Wax Crystal Morphology on Broccoli Floret Surfaces

2.3. Determination and Analysis of FA Content in Broccoli Flower Bud Tissue

2.4. Targeted Metabolomics Profiling and Data Analysis

2.4.1. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

2.4.2. Targeted Metabolomics Data Analysis

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.5.1. RNA Extraction and Quality Control of Broccoli Florets

2.5.2. Library Construction and Reference Sequence Analysis

2.5.3. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes and Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Data

2.6.1. Transcription Factor and Target Gene Prediction

2.6.2. Regulatory Network Construction

2.6.3. RT-qPCR Validation

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Observation on Wax Morphological Structure and Determination of FA Content in Broccoli Flower Bud Tissue

3.2. Targeted Metabolomic Profiling

3.2.1. Quality Assessment of Fatty Acid Metabolomics in Broccoli Florets

3.2.2. Identification and Enrichment Analysis of Differential Fatty Acid Metabolites in Broccoli Florets

3.3. Transcriptomic Analysis

3.3.1. Quality Assessment of Broccoli Floret Transcriptome Sequencing

3.3.2. Statistical Analysis and Functional Enrichment of DEGs in Broccoli Florets

3.4. Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiles in Broccoli Florets

3.4.1. Key KEGG Pathway Analysis

3.4.2. Integrated Analysis of DEGs and DAMs in Wax Biosynthesis Pathways

3.4.3. Integrated Analysis of Transcription Factors Related to Wax Biosynthesis

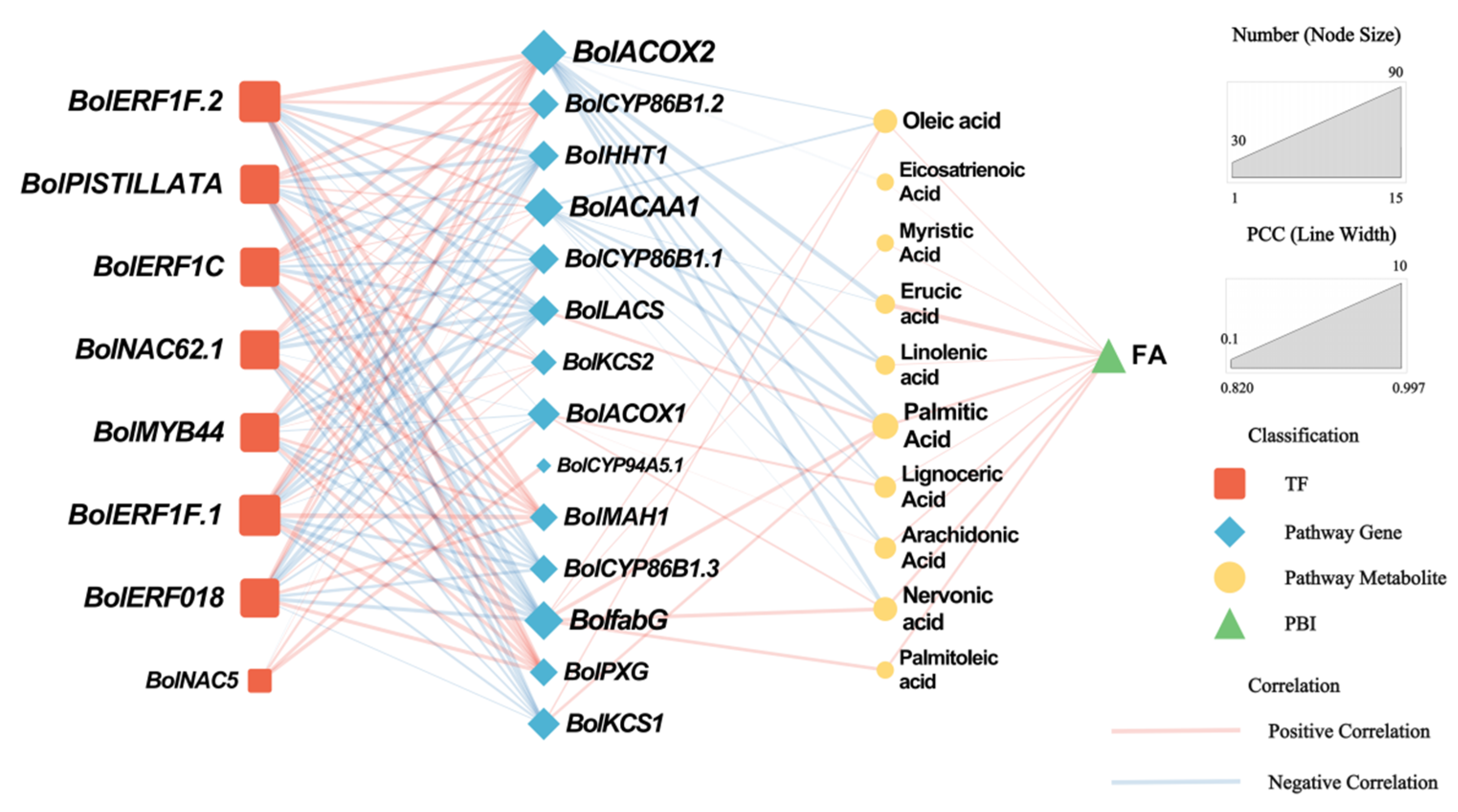

3.4.4. Construction of Regulatory Networks Related to the Wax Biosynthesis Pathway

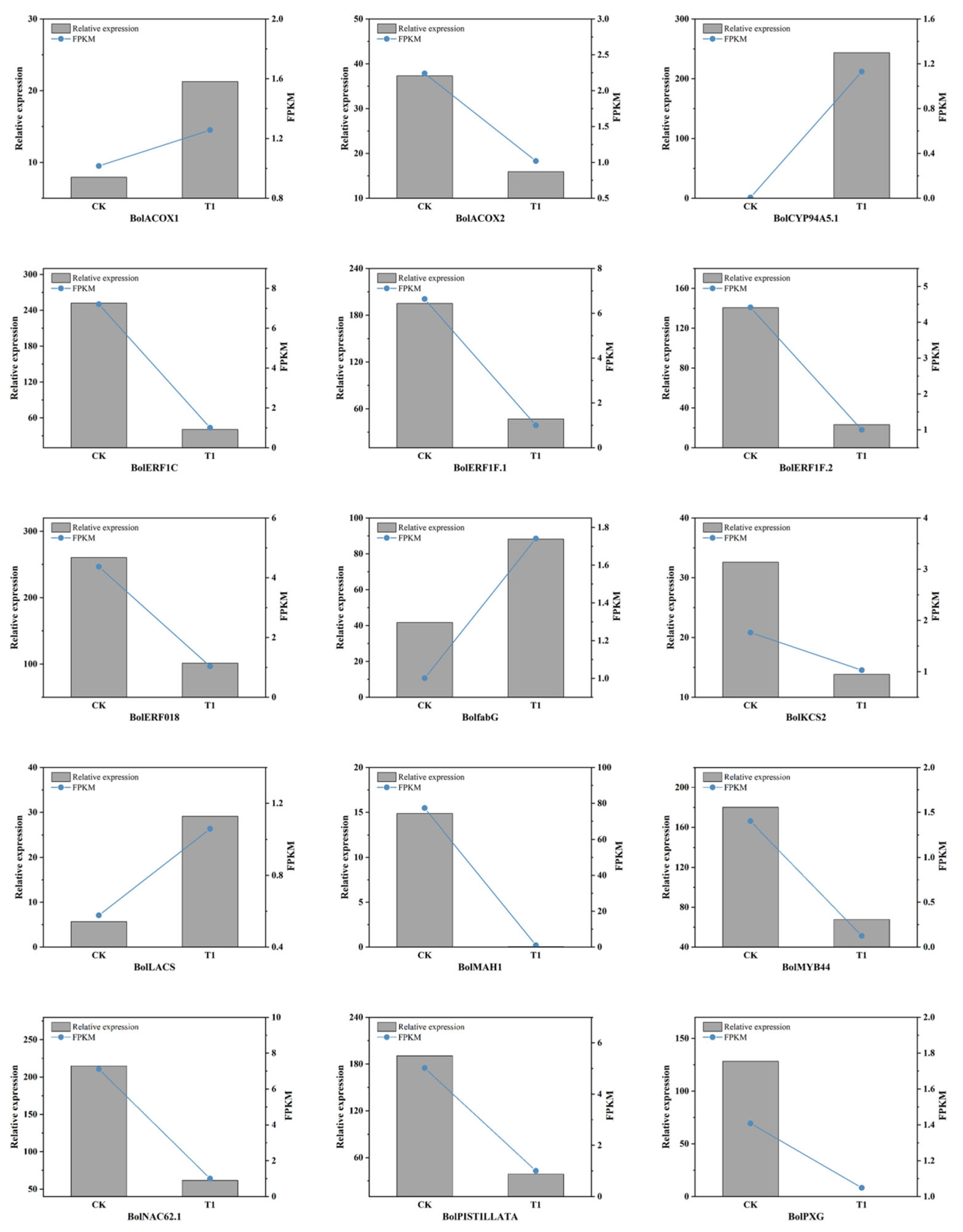

3.4.5. Experimental Validation by RT-qPCR

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Wax Accumulation on the Surface of Broccoli Flower Buds

4.2. Metabolic Differences in Fatty Acids in Broccoli Flower Buds

4.3. Analysis of Regulatory Networks Related to Waxy Biosynthesis Pathway

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Xia, Y.; Liu, H.Y.; Guo, H.; He, X.Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, D.T.; Mai, Y.H.; Li, H.B.; Zou, L.; et al. Nutritional Values, Beneficial Effects, and Food Applications of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea Var. italica Plenck). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, T.; Gerszberg, A.; Durańska, P.; Biłas, R.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K. High Efficiency Transformation of Brassica oleracea var. botrytis Plants by Rhizobium rhizogenes. AMB Express 2018, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Motaal, A.A.A. Sulforaphane Composition, Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activity of Crucifer Vegetables. J. Adv. Res. 2010, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Shi, J.; Yuan, S.; Xu, D.; Zheng, S.; Gao, L.; Wu, C.; Zuo, J.; Wang, Q. Whole-Transcriptome RNA Sequencing Highlights the Molecular Mechanisms Associated with the Maintenance of Postharvest Quality in Broccoli by Red LED Irradiation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 188, 111878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Tao, M.Q.; Pan, Y.F.; Dai, Z.L.; Yao, Y.M. Transcriptome Analysis and Mining of Genes Related to Wax Powder Synthesis of Broccoli Flower Buds. J. South. Agric. 2022, 53, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, E.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Heredia, A. The Biophysical Design of Plant Cuticles: An Overview. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Is Up-Regulated by the MYB94 Transcription Factor in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthlott, W.; Mail, M.; Bhushan, B.; Koch, K. Plant Surfaces: Structures and Functions for Biomimetic Innovations. Nano-Micro Lett. 2017, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenks, M.A.; Tuttle, H.A.; Eigenbrode, S.D.; Feldmann, K.A. Leaf Epicuticular Waxes of the Eceriferum Mutants in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1995, 108, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.L.; Wang, C.; Wang, S. Observation of Ultra Microstructure of Wax-Less Mutant Epicuticular Wax on Cabbage. China Veg. 2013, 4, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Segado, P.; Domínguez, E.; Heredia, A. Ultrastructure of the Epidermal Cell Wall and Cuticle of Tomato Fruit (Solanum lycopersicum L.) during Development. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Kovalchuk, N.; Langridge, P.; Tricker, P.J.; Lopato, S.; Borisjuk, N. The Impact of Drought on Wheat Leaf Cuticle Properties. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Xu, S.; Tao, H.; Cao, W. Research Progress of Plant Wax Synthesis and Transport Mechanism. Mol. Plant Breed. 2017, 15, 3731–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.; Sancho Knapik, D.; Gil Pelegrín, E.; Leide, J.; Peguero Pina, J.J.; Burghardt, M.; Riederer, M. Cuticular Wax Coverage and Its Transpiration Barrier Properties in Quercus coccifera L. Leaves: Does the Environment Matter? Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventure, G.; Salas, J.J.; Pollard, M.R.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Disruption of the FATB Gene in Arabidopsis Demonstrates an Essential Role of Saturated Fatty Acids in Plant Growth. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, J.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. The Acyl-CoA Synthetase Encoded by LACS2 Is Essential for Normal Cuticle Development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Haslam, T.M.; Sonntag, A.; Molina, I.; Kunst, L. Functional Overlap of Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Synthetases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Molina, I.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. Organ Fusion and Defective Cuticle Function in a Lacs1lacs2 Double Mutant of Arabidopsis. Planta 2010, 231, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, D.; Olbrich, A.; Knüfer, J.; Krüger, A.; Hoppert, M.; Polle, A.; Fulda, M. Combined Activity of LACS1 and LACS4 Is Required for Proper Pollen Coat Formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 68, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Beisson, Y.; Beisson, F.; Riekhof, W. Metabolism of Acyl-Lipids in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 2015, 82, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Cahoon, R.; Markham, J.E.; Cahoon, E.B.; Suh, M.C. Arabidopsis 3-Ketoacyl-Coenzyme A Synthase9 Is Involved in the Synthesis of Tetracosanoic Acids as Precursors of Cuticular Waxes, Suberins, Sphingolipids, and Phospholipids. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.C.; Samuels, A.L.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L.; Pollard, M.; Ohlrogge, J.; Beisson, F. Cuticular Lipid Composition, Surface Structure, and Gene Expression in Arabidopsis Stem Epidermis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1649–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Jung, S.J.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.U.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, H.J.; Park, O.K.; Suh, M.C. Two Arabidopsis 3-Ketoacyl CoA Synthase Genes, KCS20 and KCS2/DAISY, Are Functionally Redundant in Cuticular Wax and Root Suberin Biosynthesis, but Differentially Controlled by Osmotic Stress. Plant J. 2009, 60, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, T.S.; Millar, A.A.; Kunst, L. Significance of the Expression of the CER6 Condensing Enzyme for Cuticular Wax Production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, F.; Wu, X.; Li, F.; Haslam, R.P.; Markham, J.E.; Zheng, H.; Napier, J.A.; Kunst, L. Functional Characterization of the Arabidopsis β-Ketoacyl-Coenzyme A Reductase Candidates of the Fatty Acid Elongase. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1174–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudier, F.; Gissot, L.; Beaudoin, F.; Haslam, R.; Michaelson, L.; Marion, J.; Molino, D.; Lima, A.; Bach, L.; Morin, H.; et al. Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acids Are Involved in Polar Auxin Transport and Developmental Patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Guo, W.; Guo, X.; Yang, L.; Hu, W.; Kuang, L.; Huang, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y. Ectopic Overexpression of CsECR from Navel Orange Increases Cuticular Wax Accumulation in Tomato and Enhances Its Tolerance to Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 924552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.; Joubès, J. Arabidopsis Cuticular Waxes: Advances in Synthesis, Export and Regulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Jetter, R.; Ni, Y. Exogenous Hormones Influence Brassica Napus Leaf Cuticular Wax Deposition and Cuticle Function. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. Progress in Research on Plant Cuticular Wax and Related Genes. Plant Physiol. J. 2016, 52, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, O.; Zheng, H.; Hepworth, S.R.; Lam, P.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L. CER4 Encodes an Alcohol-Forming Fatty Acyl-Coenzyme A Reductase Involved in Cuticular Wax Production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wu, X.; Lam, P.; Bird, D.; Zheng, H.; Samuels, L.; Jetter, R.; Kunst, L. Identification of the Wax Ester Synthase/Acyl-Coenzyme A: Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase WSD1 Required for Stem Wax Ester Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdenx, B.; Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Léger, A.; Roby, D.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 Promotes Wax Very-Long-Chain Alkane Biosynthesis and Influences Plant Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Jetter, R.; Renne, C.; Faure, J.-D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Lessire, R.; Joubès, J. Reconstitution of Plant Alkane Biosynthesis in Yeast Demonstrates That Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 and ECERIFERUM3 Are Core Components of a Very-Long-Chain Alkane Synthesis Complex. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3106–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Gao, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhu, L.; Xu, P.; Yi, B.; Wen, J.; Tu, J.; Ma, C.; et al. A Novel Dominant Glossy Mutation Causes Suppression of Wax Biosynthesis Pathway and Deficiency of Cuticular Wax in Brassica Napus. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, G.; Wang, N.; Huang, S.; Gao, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhang, M.; Feng, H. A Single SNP in Brcer1 Results in Wax Deficiency in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ssp. pekinensis). Sci. Hortic. 2021, 282, 110019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Jiang, Q.; Wei, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, Z. Tomato SlCER1–1 Catalyzes the Synthesis of Wax Alkanes, Increasing Drought Tolerance and Fruit Storability. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Black, K.; Gai, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, H. Cucumber ECERIFERUM1 (CsCER1), Which Influences the Cuticle Properties and Drought Tolerance of Cucumber, Plays a Key Role in VLC Alkanes Biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 87, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemal, R.; Khoudi, H. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of a Novel WIN1/SHN1 Ethylene-Responsive Transcription Factor TdSHN1 from Durum Wheat (Triticum turgidum. L. subsp. durum). Protoplasma 2015, 252, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Li, S.; He, S.; Waßmann, F.; Yu, C.; Qin, G.; Schreiber, L.; Qu, L.-J.; Gu, H. CFL1, a WW Domain Protein, Regulates Cuticle Development by Modulating the Function of HDG1, a Class IV Homeodomain Transcription Factor, in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3392–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Go, Y.S.; Suh, M.C. DEWAX2 Transcription Factor Negatively Regulates Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis Leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Recent Advances in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis and Its Regulation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Luo, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C.; Ni, Z.; Zhu, H.; Niu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Quan, L. Effect of Drought Stress on Wax Accumulation in Leaves of Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). J. Northwest AF Univ. Sci Ed 2017, 45, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Suh, M.C. Arabidopsis Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis Is Negatively Regulated by the DEWAX Gene Encoding an AP2/ERF-Type Transcription Factor. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, P.J.; Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C.; Park, M.J.; Go, Y.S.; Park, C.M. The MYB96 Transcription Factor Regulates Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis under Drought Conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S. Lipid Transfer Protein 3 as a Target of MYB96 Mediates Freezing and Drought Stress in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Schnables, P. Research Progress on Genetic Mechanisms of Plant Epidermal Wax Synthesis, Transport and Regulation. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, M.; Keyl, A.; Feussner, I. Wax Biosynthesis in Response to Danger: Its Regulation upon Abiotic and Biotic Stress. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, S.A.; Shoaib, R.M.; Hashish, K.I.; El-Tayeb, T.A. In Vitro Ultraviolet Radiation Effects on Growth, Chemical Constituents and Molecular Aspects of Spathiphyllum Plant. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosma, D.K.; Bourdenx, B.; Bernard, A.; Parsons, E.P.; Lü, S.; Joubès, J.; Jenks, M.A. The Impact of Water Deficiency on Leaf Cuticle Lipids of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, E.; Heredia Guerrero, J.A.; Benítez, J.J.; Heredia, A. Self-Assembly of Supramolecular Lipidnanoparticles in the Formation of Plant Biopolyester Cutin. Mol. Biosyst. 2010, 6, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, A.C.; Burghardt, M.; Riederer, M. The Ecophysiology of Leaf Cuticular Transpiration: Are Cuticular Water Permeabilities Adapted to Ecological Conditions? J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5271–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Y.; He, L.; Yang, J.; Fernie, A.R.; Luo, J. Natural Variance at the Interface of Plant Primary and Specialized Metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 67, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.B.; Broadhurst, D.; Begley, P.; Zelena, E.; Francis-McIntyre, S.; Anderson, N.; Brown, M.; Knowles, J.D.; Halsall, A.; Haselden, J.N.; et al. Procedures for Large-Scale Metabolic Profiling of Serum and Plasma Using Gas Chromatography and Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 1060–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript Assembly and Quantification by RNA-Seq Reveals Unannotated Transcripts and Isoform Switching during Cell Differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, J.P.; Lee, H.K.; Boschiero, C.; Griffiths, M.; Lee, S.; Zhao, P.; York, L.M.; Mysore, K.S. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Protein NITROGEN FIXATION S-LIKE 1 and Its Interactor FRATAXIN Function in Plant Immunity. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 1532–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, G.; Gong, X.; Dang, K.; Yang, Q.; Feng, B. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanism Associated with Dynamic Changes in Fatty Acid and Phytosterol Content in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica) during Seed Development. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, D.; Li, Z.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Integration of Transcriptomic and Metabonomic Reveals Molecular Differences of Sweetness and Aroma between Postharvest and Vine Ripened Tomato Fruit. Food Control 2022, 139, 109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Maren, N.A.; Kosentka, P.Z.; Liao, Y.Y.; Lu, H.; Duduit, J.R.; Huang, D.; Ashrafi, H.; Zhao, T.; Huerta, A.I.; et al. An Optimized Protocol for Stepwise Optimization of Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno Pérez, A.J.; Venegas Calerón, M.; Vaistij, F.E.; Salas, J.J.; Larson, T.R.; Garcés, R.; Graham, I.A.; Martínez-Force, E. Reduced Expression of FatA Thioesterases in Arabidopsis Affects the Oil Content and Fatty Acid Composition of the Seeds. Planta 2012, 235, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacek, K.; Bayer, P.E.; Bartkowiak-Broda, I.; Szala, L.; Bocianowski, J.; Edwards, D.; Batley, J. Genome-Wide Association Study of Genetic Control of Seed Fatty Acid Biosynthesis in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, L.; Samuels, L. Plant Cuticles Shine: Advances in Wax Biosynthesis and Export. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, D.M.; Liu, Z.Z.; Yang, L.M.; Fang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.M.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Sun, P.T. Studies on Characteristics of Several Glossy Mutants in Cabbage. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2015, 42, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Liu, M.; Deng, C.; Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Hou, Q.; Shao, D. Analysis of Waxy Fatty Acids Composition of the Leaves in Early-maturing Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.). Mol. Plant Breed. 2025, 23, 2267–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.; Ensikat, H.J. The Hydrophobic Coatings of Plant Surfaces: Epicuticular Wax Crystals and Their Morphologies, Crystallinity and Molecular Self-Assembly. Micron 2008, 39, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.H. Molecular and Evolutionary Mechanisms of Cuticular Wax for Plant Drought Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Dou, M.; Pei, Y. Identification of Tung Tree FATB as a Promoter of 18:3 Fatty Acid Accumulation through Hydrolyzing 18:0-ACP. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. PCTOC 2021, 145, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, C.L.; Wang, G.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Qi, C.H.; You, C.X.; Li, Y.Y.; Hao, Y.J. Apple AP2/EREBP Transcription Factor MdSHINE2 Confers Drought Resistance by Regulating Wax Biosynthesis. Planta 2019, 249, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Xu, R.; Zhu, F.; Xu, J.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Y. QTL Analysis Reveals Reduction of Fruit Water Loss by NAC042 through Regulation of Cuticular Wax Synthesis in Citrus Fruit. Hortic. Plant J. 2022, 8, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Li, F. Roles of ERF2 in Apple Fruit Cuticular Wax Synthesis. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 301, 111144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, R.; Zhu, F.; Xu, J.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Y. CsERF003, CsMYB7 and CsMYB102 Promote Cuticular Wax Accumulation by Upregulating CsKCS2 at Fruit Ripening in Citrus sinensis. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 310, 111744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Xu, R.; Zhu, F.; Xu, J.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Y. CitWRKY28 and CitNAC029 Promote the Synthesis of Cuticular Wax by Activating CitKCS Gene Expression in Citrus Fruit. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound Name | CK (ng·mg−1) | T1 (ng·mg−1) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lauric Acid | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.787 |

| Myristic Acid | 0.42 | 0.55 | 0.024 |

| Myristoleic acid | 1.03 | 0.72 | 0.189 |

| Pentadecanoic Acid | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.000 |

| Palmitic Acid | 92.33 | 115.57 | 0.029 |

| Palmitoleic acid | 1.34 | 2.48 | 0.005 |

| Heptadecanoic Acid | 1.26 | 1.35 | 0.230 |

| Stearic Acid | 32.24 | 34.90 | 0.242 |

| 6-Octadecenoic acid | 2.76 | 2.53 | 0.599 |

| Oleic acid | 12.05 | 15.80 | 0.028 |

| cis-11-Octadecenoic acid | 16.09 | 31.13 | 0.000 |

| Linoleic acid | 71.02 | 69.48 | 0.757 |

| Linolenic acid | 257.92 | 327.49 | 0.018 |

| Arachidic Acid | 2.85 | 3.32 | 0.057 |

| Eicosenoic Acid | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.994 |

| Heneicosanoic Acid | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.936 |

| Eicosatetraenoic Acid | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.010 |

| Eicosatrienoic Acid | 0.87 | 1.41 | 0.025 |

| Behenic Acid | 1.00 | 1.04 | 0.651 |

| Eicosapentaenoic Acid | 5.05 | 5.24 | 0.009 |

| Erucic acid | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.001 |

| Tricosanoic Acid | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.201 |

| Lignoceric Acid | 1.82 | 2.49 | 0.012 |

| Docosapentaenoic acid | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.089 |

| Nervonic acid | 1.00 | 1.68 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shao, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Lin, H.; Cheng, S.; Lin, B.; Qiu, B.; Lin, H.; Zhu, H. Unraveling the Formation Mechanism of Wax Powder on Broccoli Curds: An Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic and Targeted Metabolomic Approach. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010005

Shao Q, Liu J, Chen M, Lin H, Cheng S, Lin B, Qiu B, Lin H, Zhu H. Unraveling the Formation Mechanism of Wax Powder on Broccoli Curds: An Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic and Targeted Metabolomic Approach. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Qingqing, Jianting Liu, Mindong Chen, Huangfang Lin, Saichuan Cheng, Biying Lin, Boyin Qiu, Honghui Lin, and Haisheng Zhu. 2026. "Unraveling the Formation Mechanism of Wax Powder on Broccoli Curds: An Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic and Targeted Metabolomic Approach" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010005

APA StyleShao, Q., Liu, J., Chen, M., Lin, H., Cheng, S., Lin, B., Qiu, B., Lin, H., & Zhu, H. (2026). Unraveling the Formation Mechanism of Wax Powder on Broccoli Curds: An Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic and Targeted Metabolomic Approach. Horticulturae, 12(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010005