1. Introduction

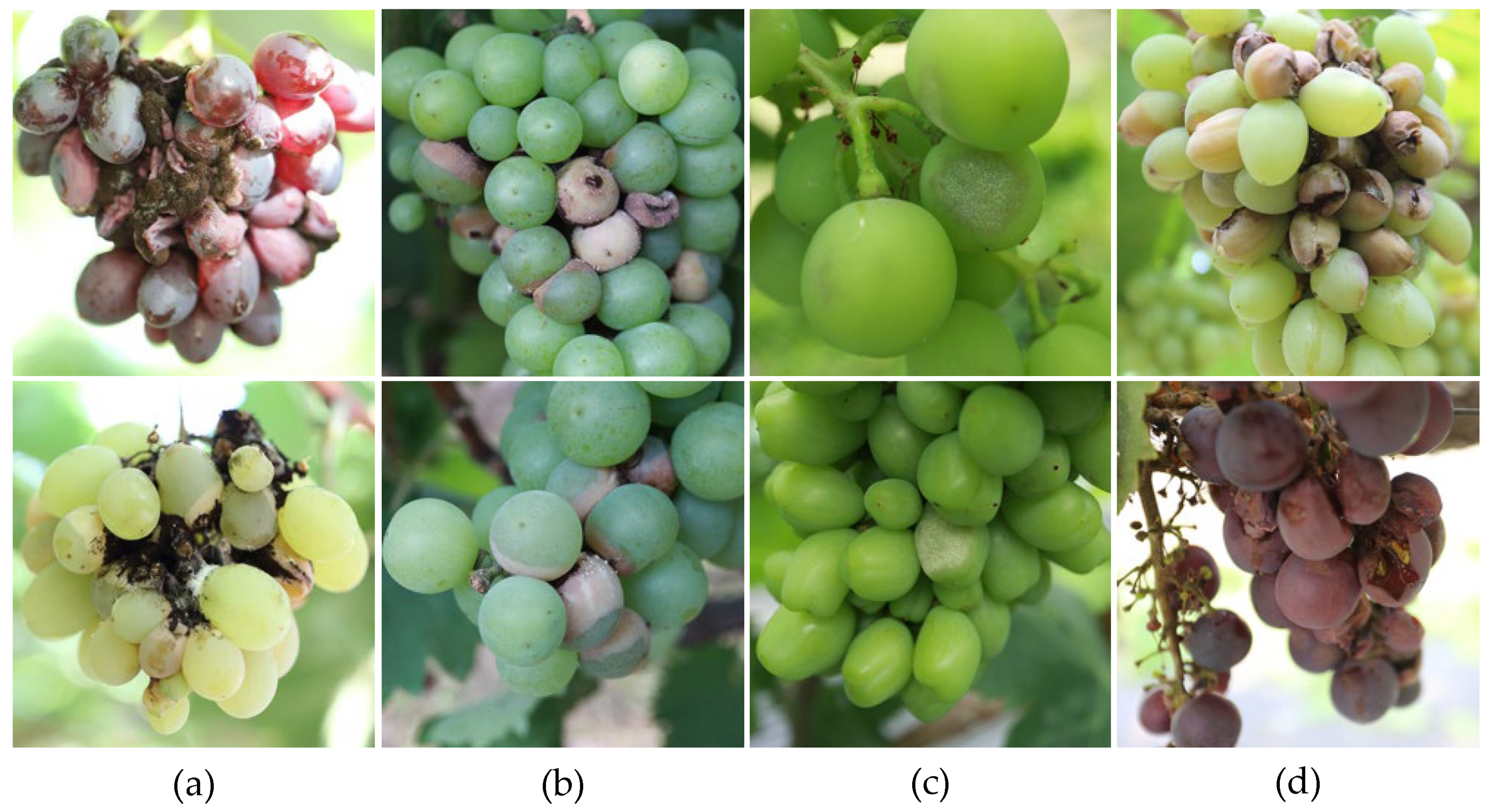

Grapes are important fruit crops that combine nutritional and economic value, playing a pivotal role in agricultural production. However, as berry plants, grapes are highly susceptible to various diseases during the growth and harvest seasons, often leading to yield reduction and quality deterioration with substantial economic losses [

1,

2]. For instance, fruit diseases such as anthracnose and gray mold not only directly compromise berry appearance and food safety, but also cause yield losses exceeding 20% during the harvest period due to fruit rotting and shedding, with severe cases even leading to total crop loss [

3]. Currently, chemical control remains the primary approach to managing grape diseases, but excessive reliance on pesticides may not only induce pathogen resistance but also pose prominent issues such as pesticide residues and environmental pollution [

4,

5]. Notably, grape berries exhibit significant differences in disease susceptibility across different growth stages. During harvest, the dense clustering and mutual contact of berries, coupled with restrictions on chemical pesticide use, further facilitate disease spread [

6]. Therefore, achieving accurate and rapid detection of fruit diseases at this stage is of great significance for ensuring the quality of fresh-eating and processed products, formulating timely harvest strategies, and optimizing postharvest grading processes.

Currently, the detection of grape berry diseases primarily relies on manual observation and empirical judgment by growers. This approach is not only costly and inefficient during the harvest season but is also highly susceptible to interference from variable lighting, occlusion within fruit clusters, and complex field conditions, leading to a high rate of misclassification. Consequently, it fails to meet the demands of modern viticulture for rigorous quality control and precise disease management [

7,

8,

9]. The introduction of machine learning has significantly improved disease diagnosis through computer vision and image processing techniques. However, conventional methods often depend on handcrafted feature extraction algorithms, which typically exhibit limited generalization and poor robustness when identifying multiple diseases under complex field conditions. In practical scenarios characterized by overlapping berries, varying lesion sizes, and uneven illumination, these methods are prone to missed detections and false positives, thereby hindering the widespread application of computer vision in large-scale, automated harvest sorting [

10,

11].

The advent of deep learning has brought transformative changes to this field. Unlike traditional computer vision methods that depend on handcrafted features, deep learning utilizes its powerful end-to-end learning capability to automatically extract hierarchical discriminative features directly from raw images. This approach effectively captures subtle visual patterns of diseases, thereby significantly improving detection accuracy and efficiency [

12,

13,

14]. The emergence of lightweight network architectures has been particularly impactful, reducing computational complexity and parameter counts. This optimization enables real-time inference on resource-constrained devices, such as embedded systems or mobile platforms, providing feasible technical support for rapid in-field disease diagnosis in agricultural production [

15,

16]. Consequently, such methods have been extensively adopted for crop disease detection tasks. In grape disease research, scholars have actively explored and refined various deep learning models to overcome detection challenges in complex orchard environments, continually enhancing their practicality and robustness. For instance, Wu et al. [

17] developed GC-MobileNet, a model based on MobileNetV3, for efficient classification and fine-grained severity assessment of grape leaf diseases. By integrating Ghost modules to replace certain inverted residual structures, the model significantly reduced its parameter count while enhancing feature extraction efficiency. The incorporation of the CBAM attention mechanism strengthened spatial and channel feature representation, and the use of the LeakyReLU activation function helped retain both positive and negative feature information. Combined with transfer learning and data augmentation strategies, these improvements enabled the model to achieve a classification accuracy of 98.63%. To address detection in complex environments, Cai et al. [

18] proposed a Siamese network (Siamese DWOAM-DRNet). This model employs a dual-factor weight optimization attention mechanism (DWOAM) to enhance disease feature extraction and suppress background interference. It also utilizes diverse branch residual modules (DRM) to enrich feature representation and adopts a combined loss function to improve discrimination between similar diseases. Experimental results demonstrated a detection accuracy of 93.26%, confirming the model’s effectiveness in classifying disease images under natural conditions. Zhang et al. [

19] introduced DLVTNet, a lightweight model for grape leaf disease detection. They innovatively designed an LVT module, which combines Ghost and Transformer structures to collaboratively extract and fuse multi-scale local and global contextual features. Furthermore, dense connections between the LVT and MARI modules enhanced feature richness and improved the perception and localization of lesion areas. On the New Plant Diseases dataset, the model attained an average detection accuracy of 98.48%.

Despite significant progress in deep learning for plant disease detection, substantial challenges persist in the detection of grape berry diseases. Firstly, most existing studies focus on grape leaves, with relatively scarce research dedicated specifically to berry diseases. The lack of high-quality public datasets and practical application cases further hinders progress. As evidenced by existing works (e.g., [

17,

18,

19]), which primarily target branches and leaves, insufficient attention has been paid to berry detection under complex field conditions, thereby limiting methodological advancement and model generalization in this area. Secondly, the performance of deep learning-based detection fundamentally depends on the model’s ability to learn sufficiently rich and discriminative features. This is particularly challenging for grape berries due to their small size and the complex diversity of disease manifestations, which make detection more difficult than for common leaf diseases. Early symptoms, such as subtle spots, depressions, or mold layers, are characterized by small scales and low contrast against healthy tissues, posing significant challenges to stable feature capture and precise localization. Moreover, common diseases like anthracnose, scab, and gray mold exhibit similar visual features in early stages, while lesion size, shape, and texture change considerably as the disease progresses, further complicating model discrimination and generalization. Finally, most existing models exhibit high structural complexity and computational costs, hindering efficient inference in resource-limited settings like orchard harvest sites. This limitation also restricts their deployment on mobile or embedded platforms for real-time sorting applications.

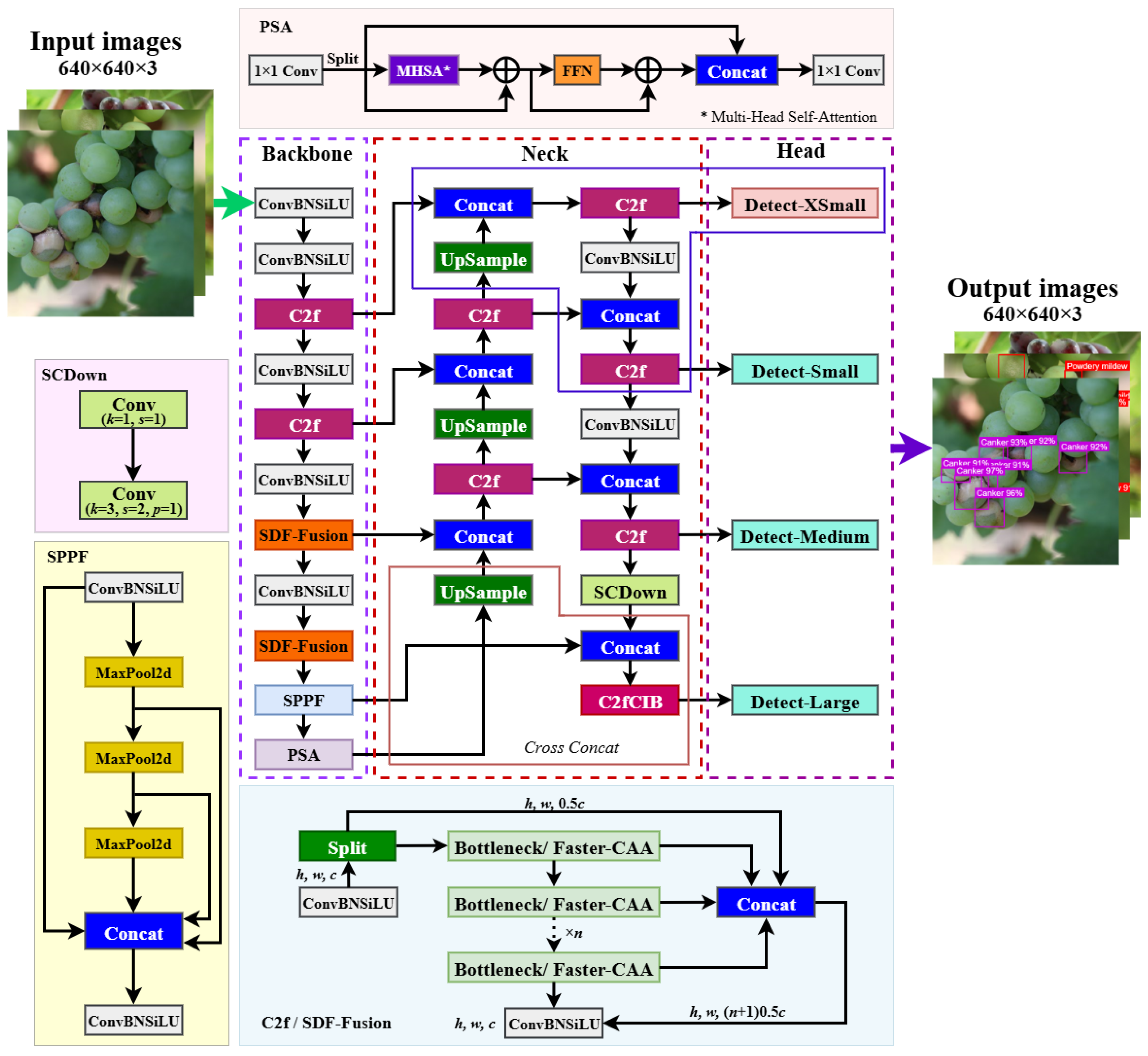

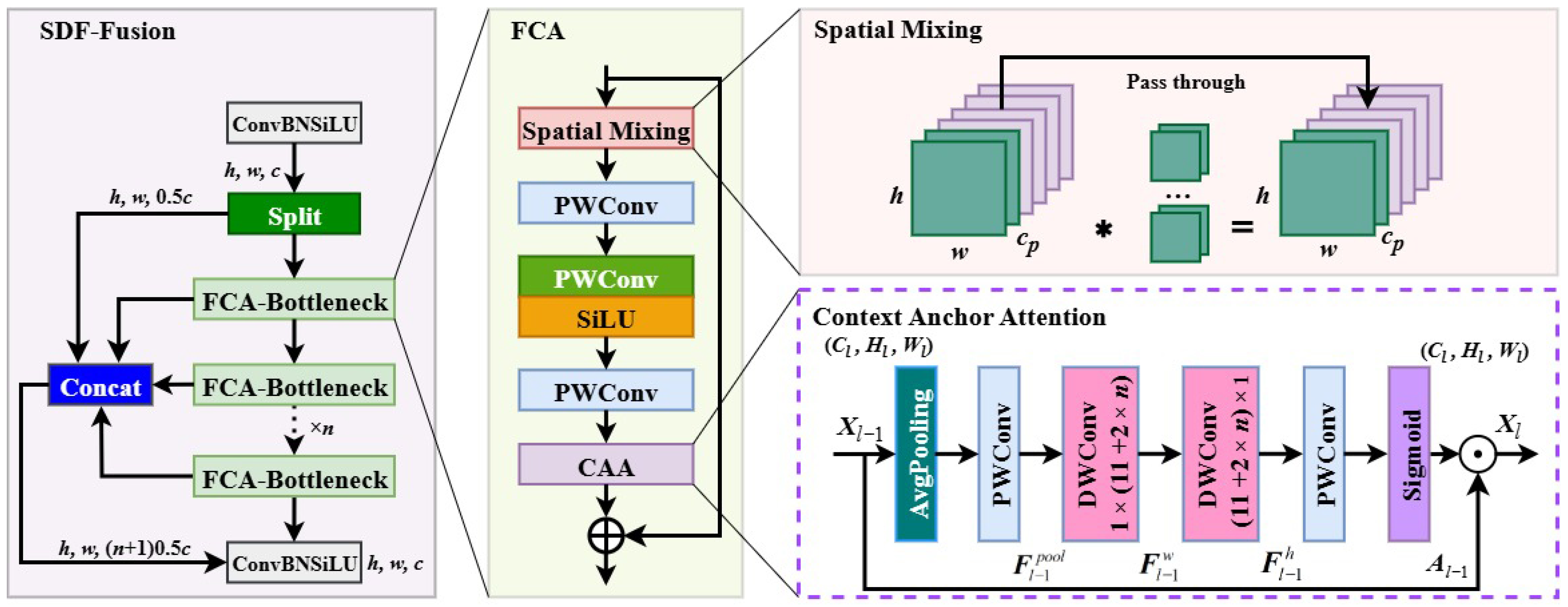

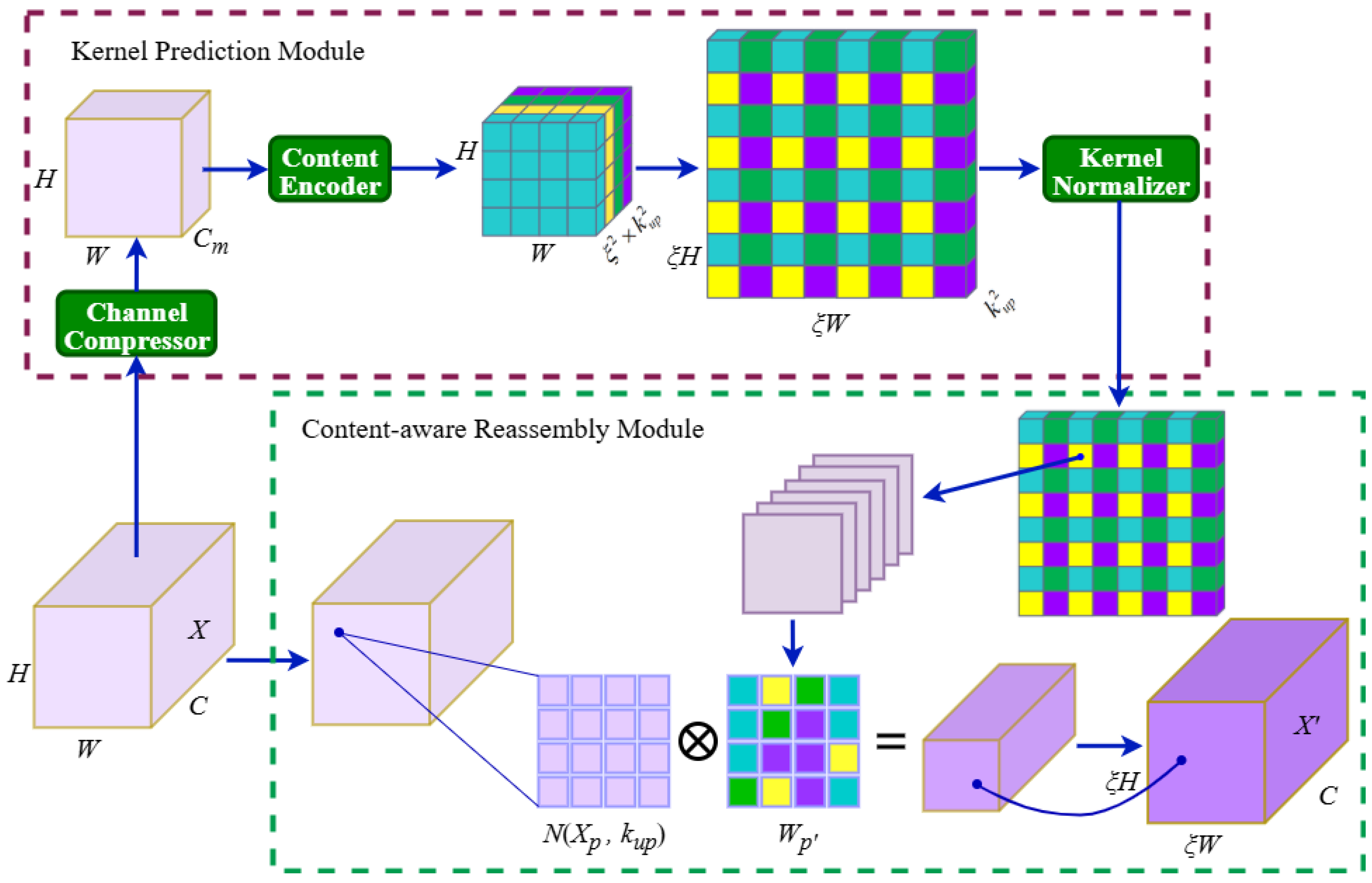

To address the aforementioned challenges and bridge the research gap in grape berry disease detection, this study proposes GBDR-Net, a detection model that integrates high accuracy, a lightweight design, and easy deployment. It aims to provide an effective technical pathway for the precise detection and real-time prevention of fruit diseases in natural environments. The design rationale of the proposed GBDR-Net model is summarized as follows: (1) built on the YOLOv10 framework, it incorporates the innovative SDF-Fusion module to enhance the backbone network’s capability of perceiving global context and subtle features; (2) an additional Detect-XSmall detection head is introduced to strengthen the recognition sensitivity of faint lesions, while the cross-concatenation strategy is adopted to achieve efficient fusion of multi-scale features; (3) a lightweight content-aware feature rearrangement operator replaces traditional upsampling methods to improve the semantic alignment quality of small-scale disease features; and (4) the traditional bounding box loss function is replaced with the Inner-SIoU loss, effectively improving the model’s convergence speed and localization accuracy. To evaluate its performance, we trained GBDR-Net on a dataset collected under field conditions and compared it with several common models.

This study provides an effective technical tool for the intelligent monitoring and precise prevention of grape berry diseases. When integrated with smart agriculture platforms and precision spraying systems, the GBDR-Net model significantly enhances the timeliness and accuracy of disease management, facilitating real-time detection and precise removal of diseased fruits during harvest to safeguard grape yield and post-harvest quality. Furthermore, this research improves the stability and resilience of vineyard production systems, contributing to the sustainable development of the horticultural industry.

4. Discussion

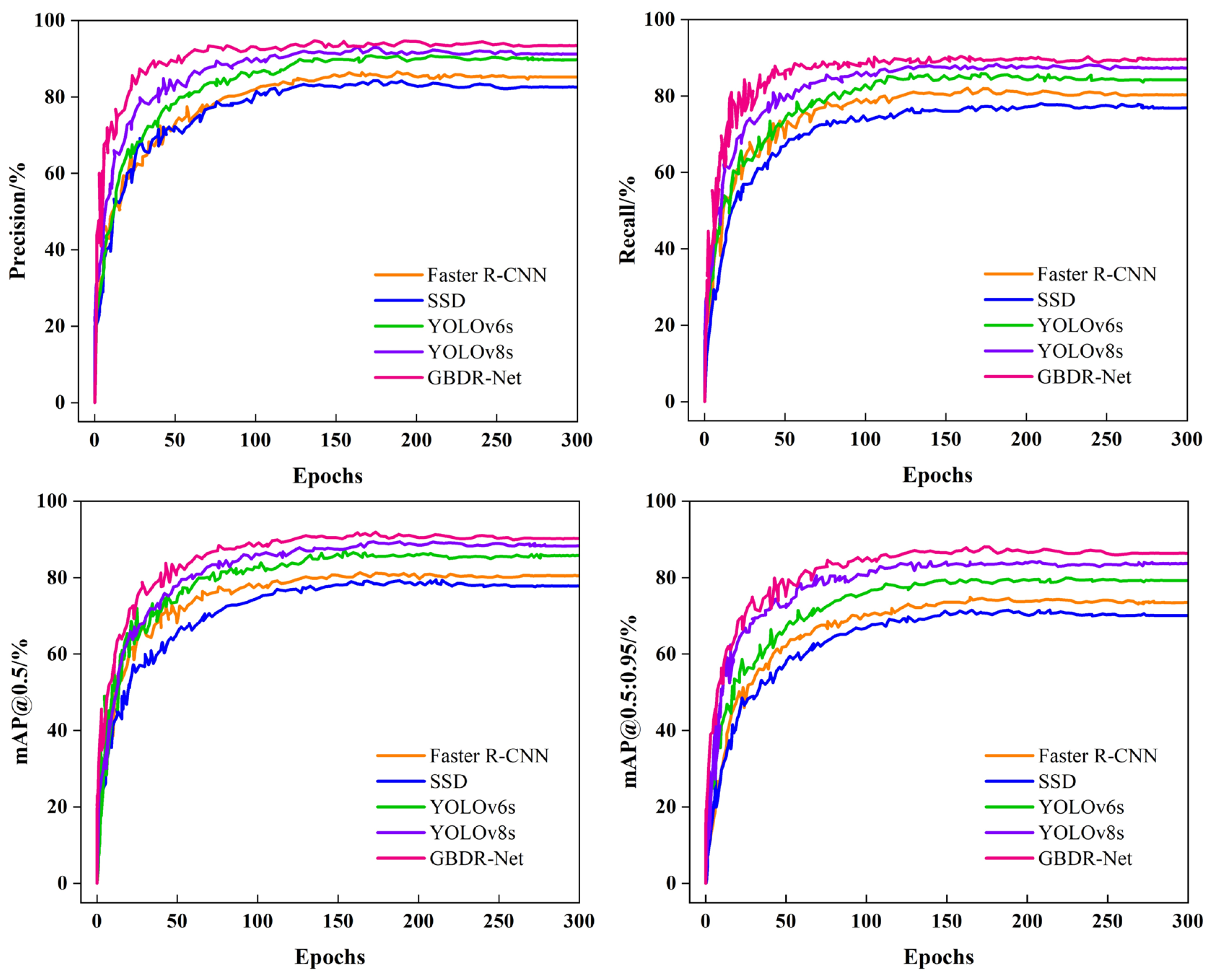

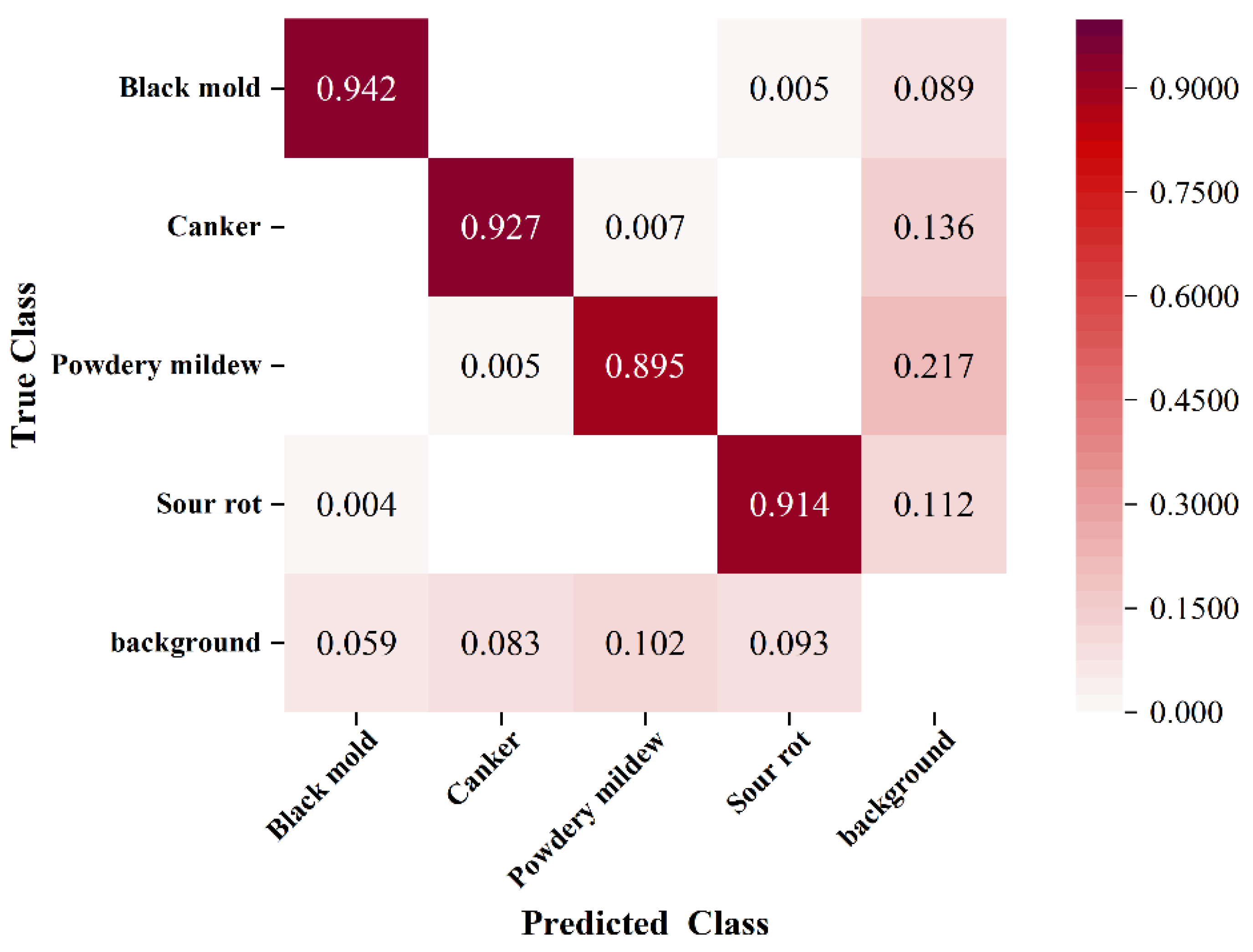

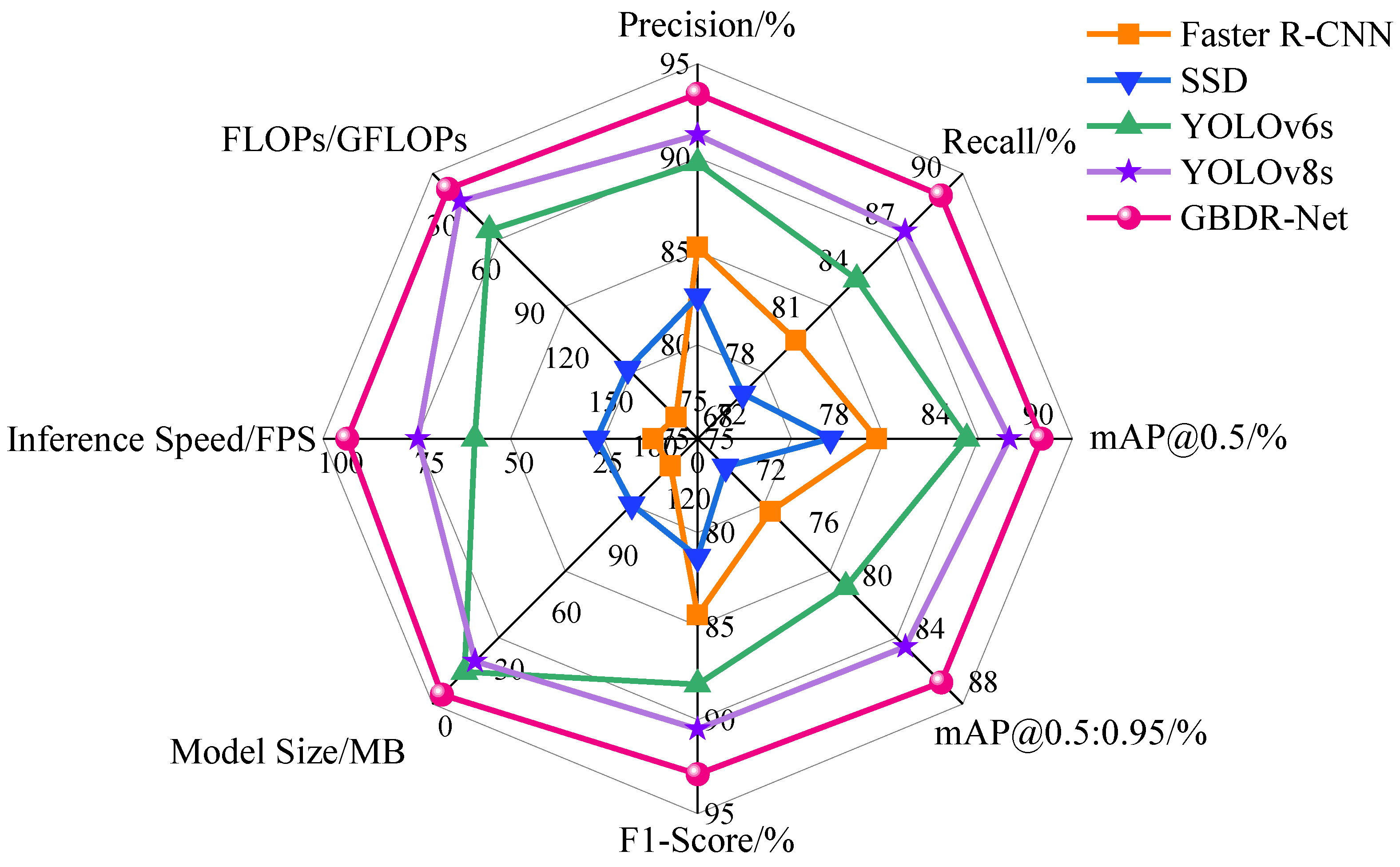

This study tackles long-standing challenges in grape berry disease detection, including the absence of specialized models for clustered fruits, inadequate accuracy in detecting small-scale lesions, and the incompatibility of complex models with resource-constrained deployment environments. On the GBDVA dataset, GBDR-Net demonstrates outstanding overall performance, achieving a precision of 93.4%, recall of 89.6%, mAP@0.5 of 90.2%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 86.4%. Furthermore, the model exhibits remarkable lightweight characteristics, with a size of 4.83 MB, a computational cost of 20.5 GFLOPs, and a real-time inference speed of 98.2 FPS, highlighting its strong deployment potential. These results collectively confirm that GBDR-Net effectively bridges the identified research gaps by striking an optimal balance between detection accuracy and practical applicability.

Compared to existing deep learning-based methods for plant disease detection, the innovation of GBDR-Net lies in its targeted design for the unique attributes of grape berries. Most previous studies (e.g., Wu et al. [

17], Cai et al. [

18], Zhang et al. [

19]) have focused on grape leaf disease detection, where lesions are generally larger and plant tissue occlusion is less severe, making feature extraction relatively easier. In contrast, grape berries are not only small in size and grow in dense clusters, but their early-stage disease spots also exhibit more subtle features that can be easily obscured by adjacent fruits or complex backgrounds. To address these challenges, the SDF-Fusion module integrated into the backbone of GBDR-Net plays a critical role. It enhances the extraction of both global contextual information and fine-grained lesion features, effectively compensating for the loss of detailed semantic information in deeper layers—a limitation of the original C2f module in YOLOv10. This design focus on prioritizing the capture of “small-scale, low-contrast features”, which are essential for early disease diagnosis, explains why GBDR-Net outperforms disease detection models tailored for leaves in fruit-specific scenarios.

The incorporation of the Detect-XSmall head and the Cross-concatenation strategy for SPPF and PSA outputs further addresses the challenge of multi-scale lesion detection. Unlike SSD or Faster R-CNN, which rely on fixed-scale feature maps and are prone to missing small lesions, GBDR-Net model’s multi-head design enables effective detection of early-stage lesions as small as 1–2 mm. This capability is particularly critical during the harvest period, when chemical control is restricted and the timely removal of infected berries becomes the only measure to prevent disease spread. Moreover, the model’s lightweight profile—with a size of only 4.83 MB and a computational cost of 20.5 GFLOPs—represents a critical step towards efficient deployment on resource-constrained hardware. This significant reduction in model complexity and computational demand, compared to mainstream detectors, establishes a strong foundation for its potential application in real-time, edge-computing scenarios such as embedded systems on sorting lines or mobile devices for field scouting. The reported high inference speed (98.2 FPS) on a high-performance GPU demonstrates the algorithm’s intrinsic efficiency; its translation into practical throughput on specific edge devices (e.g., Jetson series, Raspberry Pi) will be the focus of subsequent engineering optimization and deployment studies.

The design principles and architectural innovations of GBDR-Net, particularly its focus on capturing “small-scale, low-contrast features” in clustered environments (via SDF-Fusion) and its semantic alignment capabilities (via LCFR-Op), suggest its potential adaptability to other clustered fruits facing similar detection challenges, such as strawberries, blueberries, and raspberries. For instance, the LCFR-Op operator is designed to preserve inter-object spatial relationships, which could theoretically help mitigate false detections caused by overlapping healthy fruits in dense clusters—a common issue in strawberry disease detection. While direct validation on these crops is beyond the scope of this study and remains a subject for future work, the problem-driven design of GBDR-Net provides a potentially transferable technical framework for addressing analogous “dense growth + small-scale lesion” detection tasks in precision horticulture.

The GBDR-Net model supports the transition in sustainable agriculture from broad-spectrum chemical control to precision disease management. With a detection accuracy of 90.2% mAP@0.5, the model reliably identifies and facilitates the removal of infected berries during harvest, effectively reducing yield loss at this critical stage. Its real-time inference speed of 98.2 FPS further enables dynamic harvesting strategies. For example, if the system detects that disease incidence in the field exceeds a preset threshold, growers can prioritize harvesting healthy clusters to minimize cross-contamination risks. This capability aligns with global objectives to reduce pesticide use and enhance food safety. By providing accurate in-field disease identification, GBDR-Net helps curtail the need for pre-harvest broad-spectrum fungicides, mitigates pesticide residue risks at the source, and offers a practical pathway toward greening horticultural production systems.

In post-harvest processing, integrating GBDR-Net into automated sorting systems can effectively overcome the cost and accuracy limitations associated with heavy reliance on manual grading. With a precision of 93.4%, the model significantly reduces the misclassification of healthy fruits, while its 89.6% recall rate ensures that the vast majority of infected fruits are accurately identified and removed. This capability not only enhances end-product quality directly but also holds substantial practical significance for establishing a reliable quality control barrier at the upstream supply chain level and strengthening end-consumer trust.

Despite the significant progress achieved in this study, several limitations remain. While the current model can accurately identify disease categories, it is unable to perform fine-grained grading of infection severity. This capability gap is partly attributable to constraints in its data foundation. Above all, the GBDVA dataset used covers only four common diseases and lacks several prevalent ones such as anthracnose, as well as complex scenarios involving co-infection, thereby limiting the model’s diagnostic scope. Subsequently, all samples were collected from a single geographical region (North China) and specific orchards, lacking representation from diverse climatic zones—such as the rainy regions of Southern China or arid Northwestern China—and varied grape cultivars, which challenges the model’s generalization capability across broader real-world conditions. Ultimately, while the current GBDVA dataset primarily consists of high-resolution, close-range images that facilitate the learning of clear disease features, a gap remains between such data and the wide-angle, low-resolution scenarios commonly encountered in practical field monitoring. This highlights the need for further improvement in the model’s robustness under multi-scale imaging conditions. Nevertheless, the overall advantages and practical value of the GBDR-Net model remain substantial, positioning it as a promising solution for real-time monitoring of grape berry diseases in agricultural applications.

Based on the current research outcomes, our future work will systematically advance along five interconnected directions to further enhance intelligent grape disease detection and management. First, we plan to systematically enhance the scale diversity of the dataset. On the one hand, we will collect or integrate wide-angle images from drones, field robots, and fixed monitoring points to simulate real-world scenarios where target fruits appear smaller and at lower resolution within the image. On the other hand, a multi-scale collaborative training strategy will be designed and implemented, enabling the model to simultaneously learn from both close-range details and long-range contextual information.

Second, we will expand the dataset by incorporating high-incidence diseases such as anthracnose and black pox, along with mixed infection cases, through cross-regional sampling across diverse climatic zones including southern rainy and northwestern arid areas in China. This will establish a comprehensive multi-disease, multi-variety, multi-region, and multi-infection-type dataset to significantly improve model generalization. Third, we will strengthen fine-grained analysis capabilities by implementing a multi-task learning framework that incorporates infection severity grading alongside existing detection and classification tasks. Through optimized loss function design, the model will achieve simultaneous disease identification, severity quantification, and mixed-infection detection. Subsequently, we will focus on optimizing edge deployment efficiency by conducting performance tests on low-power devices like Raspberry Pi Zero and applying 8-bit quantization with model pruning for further compression. This will be complemented by developing mobile applications and UAV-mounted systems to enable multi-scenario deployment strategies combining handheld field inspection and large-scale aerial monitoring. Finally, we will explore multi-modal data fusion by integrating near-infrared imaging, spectral data, and RGB images to construct a unified detection framework that leverages complementary features for identifying early-stage weak symptoms and variety-specific disease manifestations. Collectively, these efforts will establish a comprehensive intelligent monitoring system characterized by broad adaptability, fine-grained classification, flexible deployment, and multi-modal perception, thereby providing stronger technical support for precision viticulture and sustainable production.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed GBDR-Net, a lightweight grape berry disease detection model specifically designed for complex orchard environments, effectively addressing the long-standing technical challenge of achieving high-precision real-time detection in dense clusters with small-scale lesions. Unlike previous studies focused primarily on leaf diseases or generic object detection, our research introduces four key improvements based on YOLOv10, achieving a synergistic breakthrough in both detection performance and practical applicability: (1) integration of the SDF-Fusion module into the backbone network to enhance the extraction of global contextual and fine-grained lesion features; (2) incorporation of a Detect-XSmall head combined with a cross-concatenation strategy in the neck network, constructing an enhanced feature pyramid that significantly improves sensitivity to small-scale disease objects; (3) proposal of the lightweight content-aware feature reorganization operator (LCFR-Op) to achieve efficient upsampling through enhanced semantic alignment; (4) adoption of the Inner-SIoU bounding box loss function, which accelerates model convergence and improves localization accuracy by introducing more refined geometric constraints.

Comprehensive evaluation experiments demonstrate that GBDR-Net model has reached the state-of-the-art level in key performance metrics. On the GBDVA dataset, it achieved a precision of 93.4%, a recall of 89.6%, and an mAP@0.5 of 90.2%—not only significantly outperforming traditional models (e.g., Faster R-CNN, SSD) but also comprehensively surpassing advanced contemporary models (e.g., YOLOv6s, YOLOv8s). Notably, with a model size of only 4.83 MB and a computational cost of 20.5 GFLOPs, the model achieves a real-time inference speed of 98.2 FPS. This marks its optimal balance across the three critical dimensions of accuracy, speed, and lightweightedness, laying a foundation for large-scale deployment on embedded devices and mobile terminals.

In summary, GBDR-Net model not only fills the critical gap for specialized high-precision detection models targeting densely clustered fruit diseases, but also delivers a comprehensive and practically viable solution for smart horticulture through its exceptional overall performance. Future research will systematically focus on enhancing generalization capability, achieving practical deployment, deepening perceptual capacity, and establishing a comprehensive system, aiming to advance this technology from a laboratory prototype toward robust field application.