Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveal the Impact of Delayed Harvest on the Aroma Profile of ‘Shine Muscat’ Grapes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Treatment

2.2. Materials and Reagents

2.3. Measurement of Berry Physiological Indicators

2.4. Measurement of Volatile Aroma Compounds

2.4.1. Preparation of Standard Solutions

2.4.2. Extraction of Volatile Aroma Compounds

2.4.3. Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Analysis

2.4.4. Establishment of GC-MS Analysis Method

2.4.5. Construction of Calibration Curves

2.4.6. Odor Activity Value (OAV)

2.5. RNA-Seq Sequencing

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of On-Vine Hanging Storage of ‘Shine Muscat’ Grapes

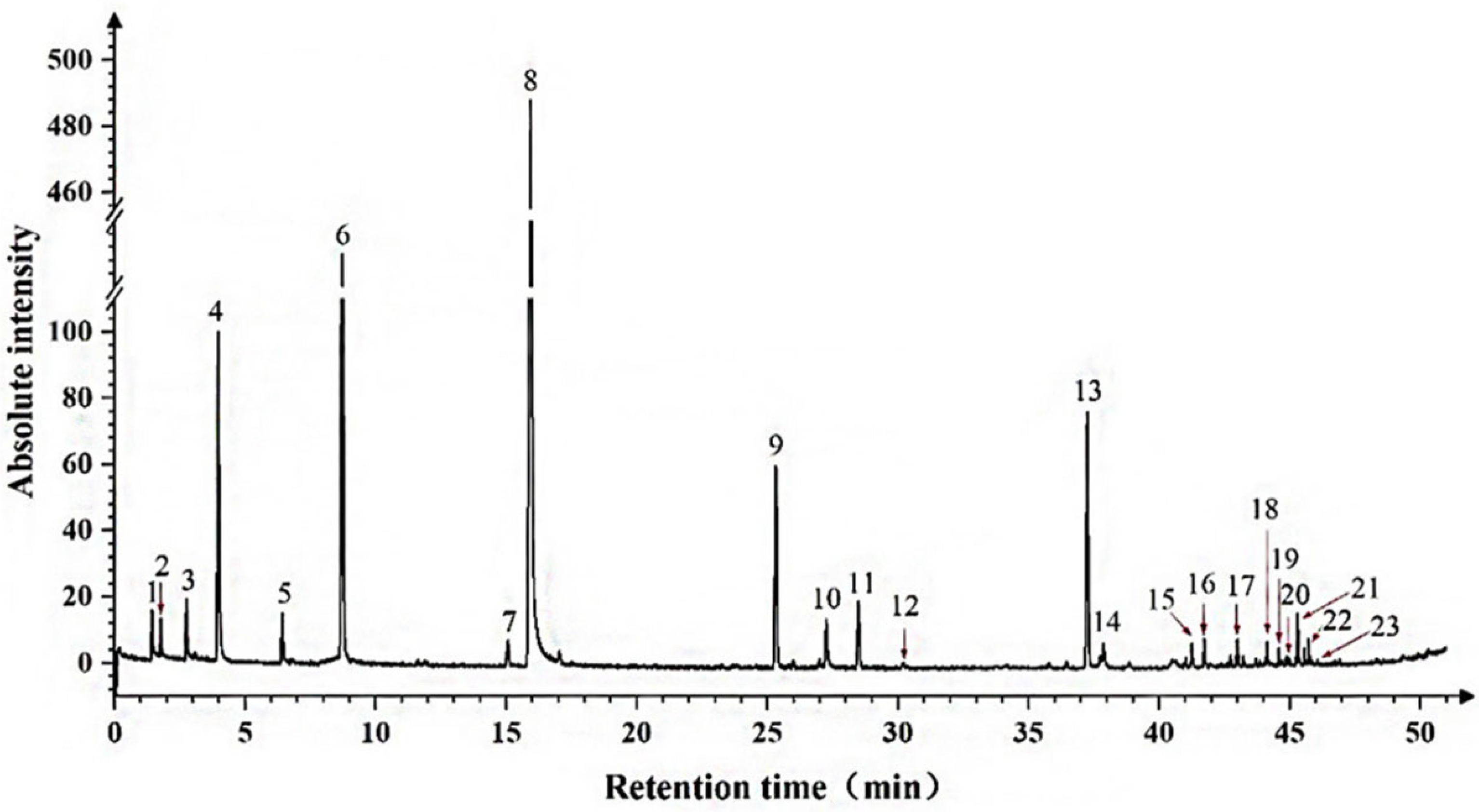

3.2. Establishment of GC-MS Analysis

3.3. Standard Curves

3.4. Analysis of Aromatic Compounds During On-Vine Hanging Storage

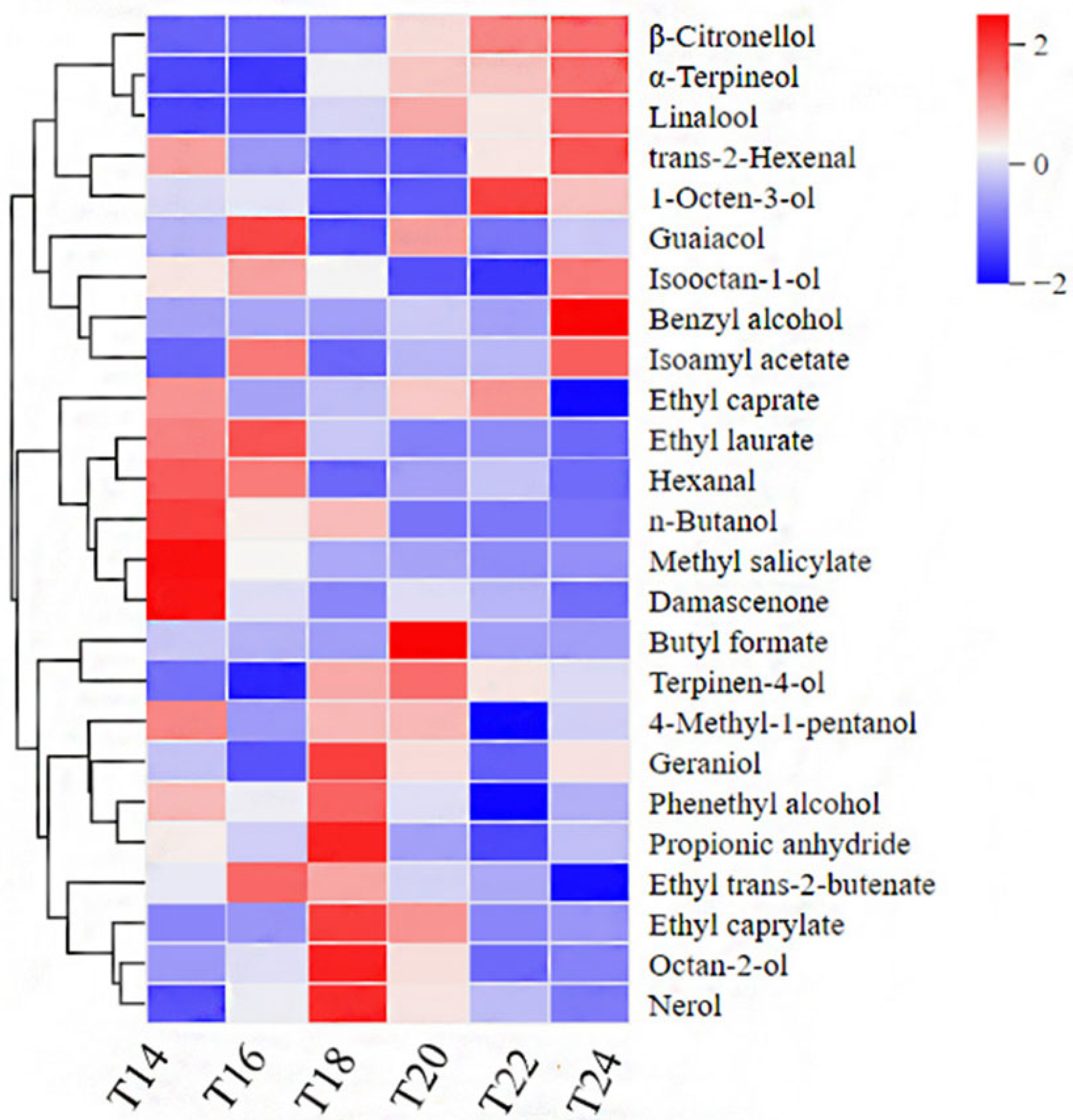

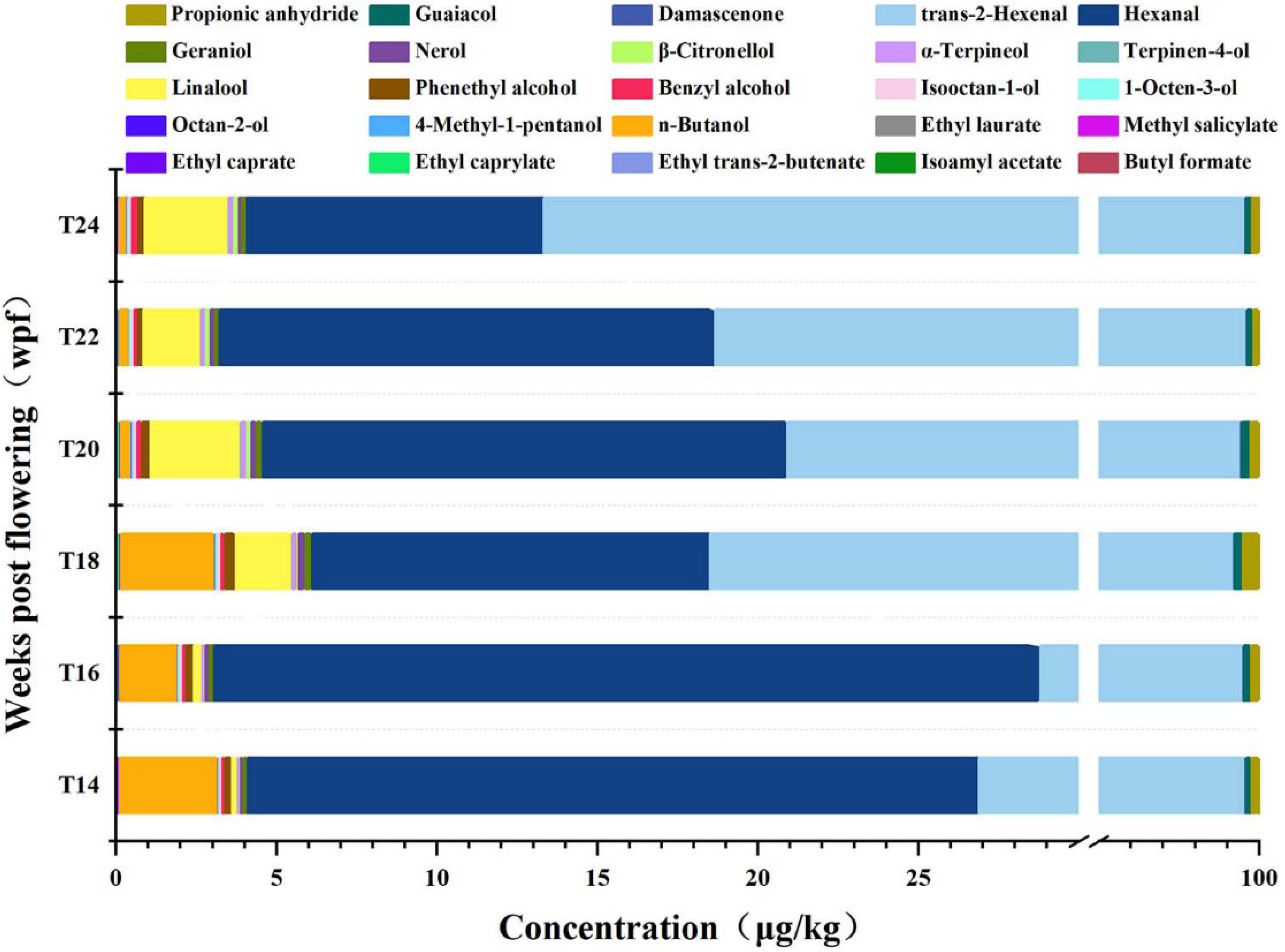

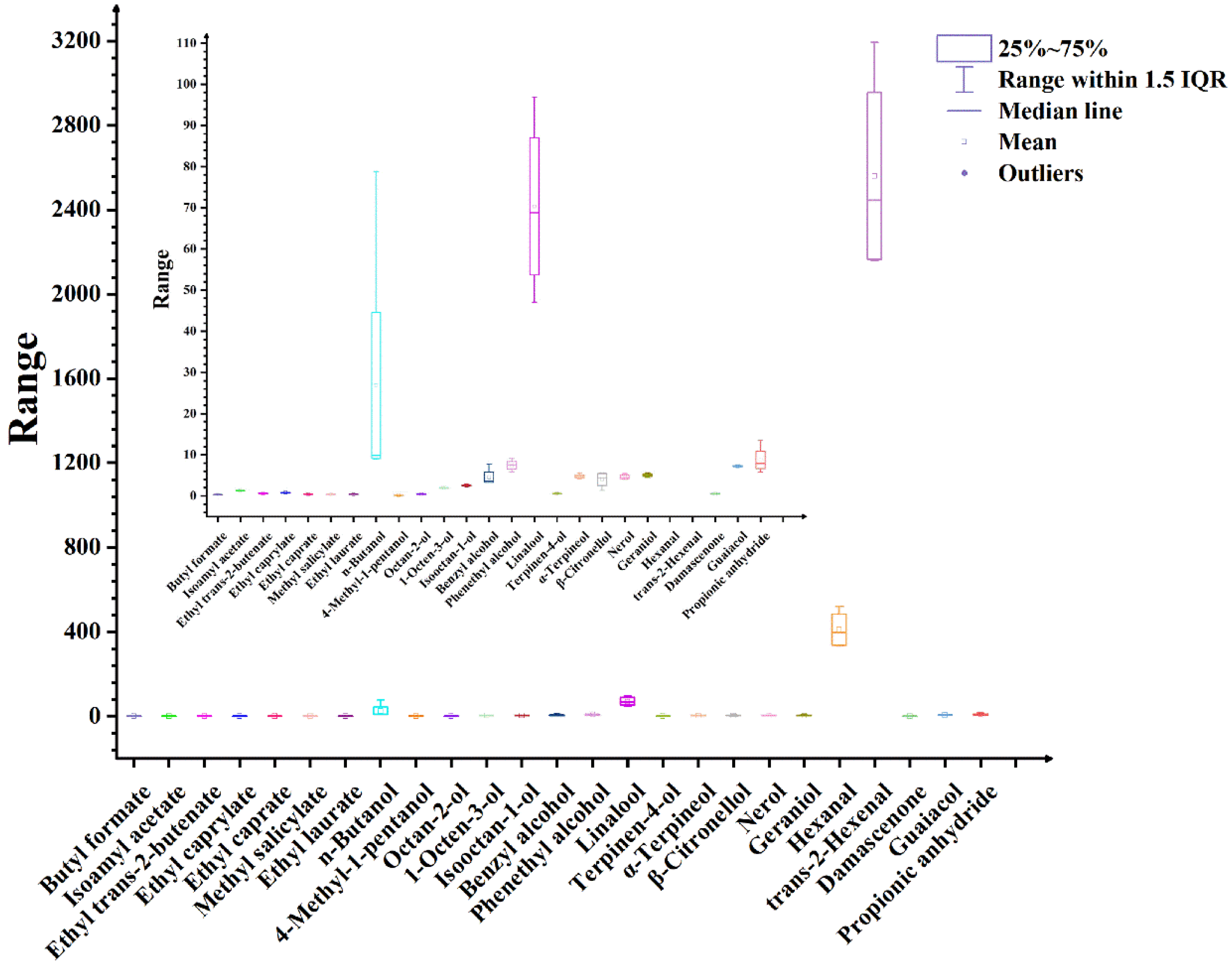

3.4.1. Changes in Volatile Aromatic Compounds During Delayed Harvest of Berries

3.4.2. Impact of Different Harvest Times on the Volatile Aroma Compounds of Berries

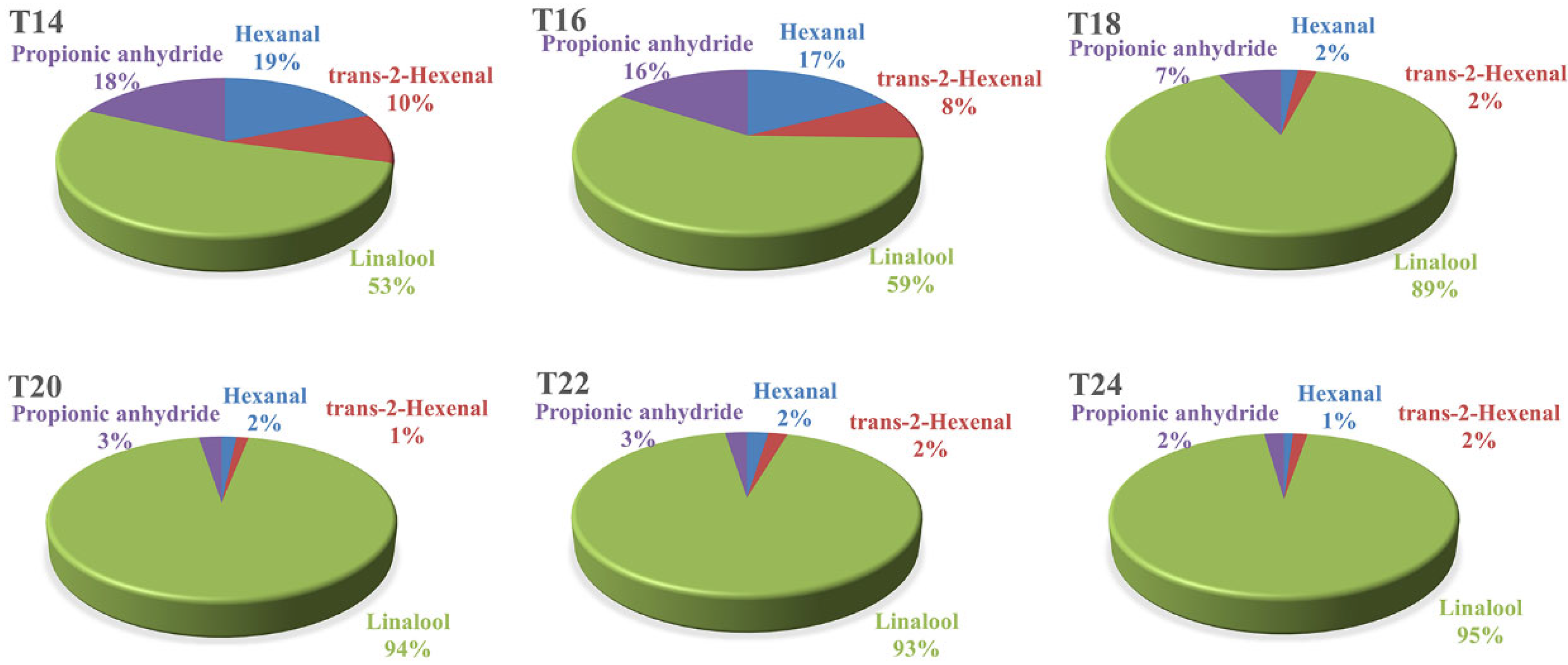

3.4.3. Changes in Volatile Aroma During Different Sample Time Delayed Harvest

3.4.4. Impact of Different Sample Time Harvest on the OAV of Characteristic Volatile Aroma Compounds

3.5. RNA-Seq Sequencing Results

3.5.1. Quality Control Data Statistics

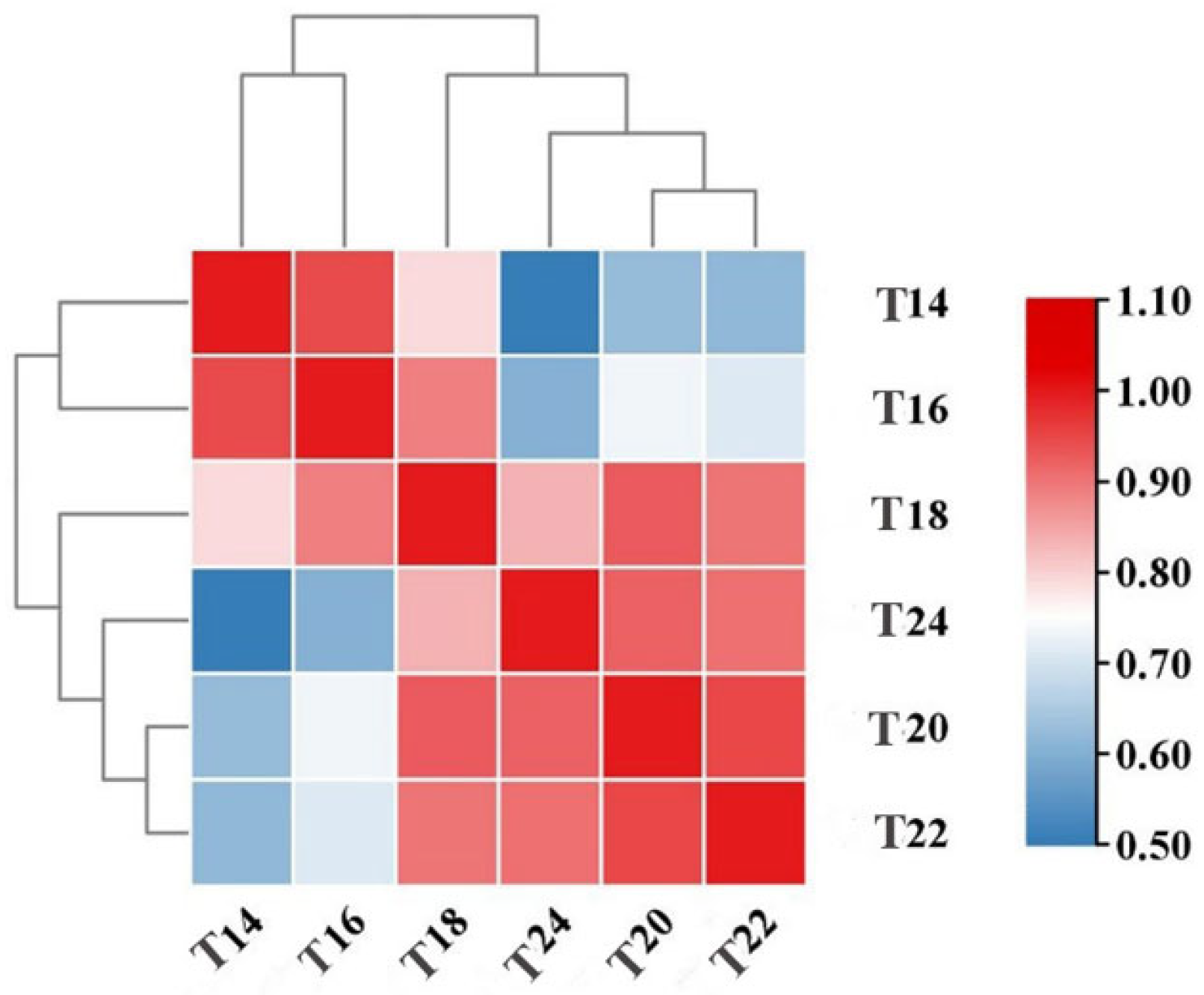

3.5.2. Correlation Analysis Between Each Samples

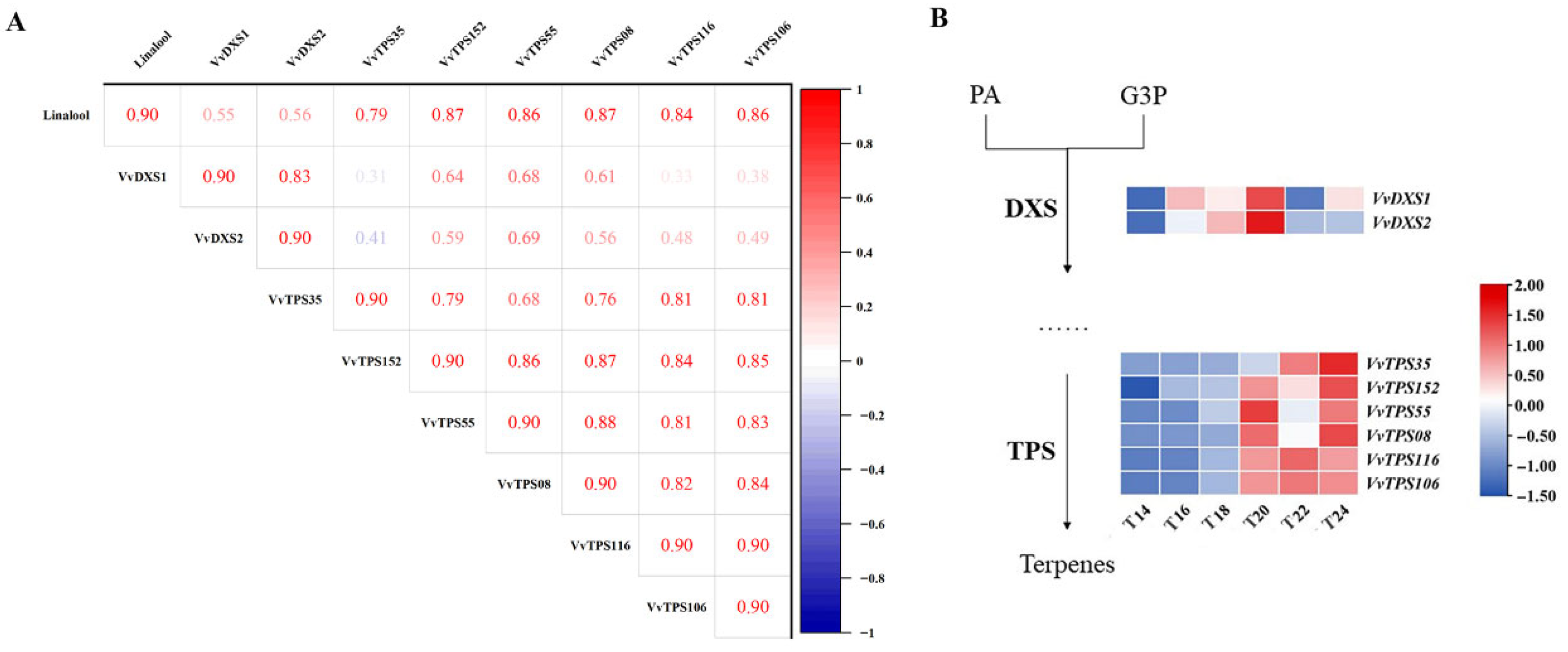

3.5.3. Differential Genes in the MEP Metabolic Pathway Involved in Linalool Synthesis

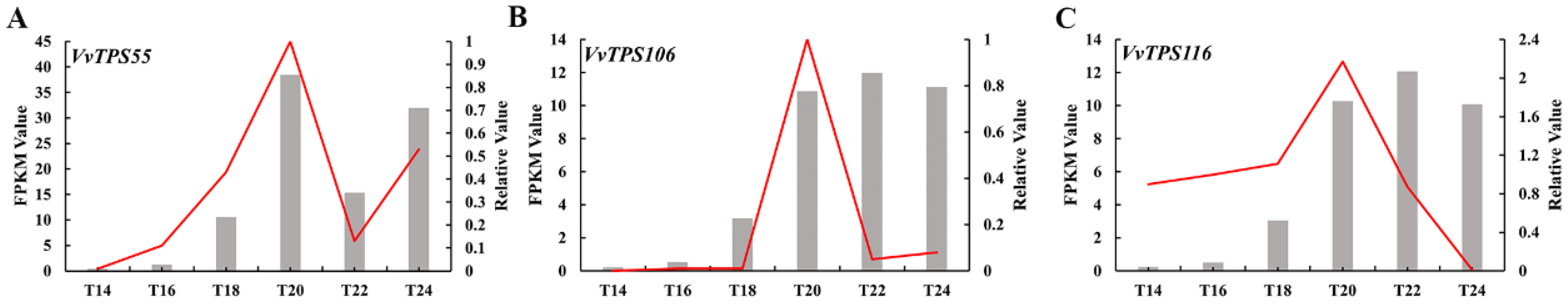

3.5.4. qRT-PCR Validation Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Bai, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, A.; Lou, B.; He, J.; Lin, L.; et al. Introduction performance and double-harvest-a-year cultivation technique of ‘Shine Muscat’ grape in Nanning, Guangxi. J. South. Agric. 2016, 47, 975–979. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, P.; Yang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Ma, J.; Li, S.; Yang, G.; Bai, M. Transcriptome analysis provides new insights into the berry size in ‘Summer Black’ grape under a two-crop-a-year cultivation system. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Alem, H.; Rigou, P.; Schneider, R.; Ojeda, H.; Torregrosa, L. Impact of agronomic practices on grape aroma composition: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Lopez, R. The Actual and Potential Aroma of Winemaking Grapes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. Green leaf volatiles: Hydroperoxide lyase pathway of oxylipin metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Fan, P.; Wu, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Volatiles of grape berries evaluated at the germplasm level by headspace-SPME with GC–MS. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, J.; Wei, L.; Khalil-Ur-Rehman, M.; Nieuwenhuizen, N.J.; Yang, L.; Zheng, H.; Tao, J. Transcriptomics Integrated with Free and Bound Terpenoid Aroma Profiling during “Shine Muscat” (Vitis labrusca × V. vinifera) Grape Berry Development Reveals Coordinate Regulation of MEP Pathway and Terpene Synthase Gene Expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Brotchie, J.; Pang, M.; Marriott, P.J.; Howell, K.; Zhang, P. Free terpene evolution during the berry maturation of five Vitis vinifera L. cultivars. Food Chem. 2019, 299, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.C.; Niu, Y.; Xiao, Z.B. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in Laoshan green teas by application of odour activity value (OAV), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-olfactometry (GC-MS-O) and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC×GC-qMS). Food Chem. 2020, 339, 128136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Genisheva, Z.; Bescansa, L.; Masa, A.; Oliveira, J.M. Changes in free and bound fractions of aroma compounds of four Vitis vinifera cultivars at the last ripening stages. Phytochemistry 2012, 74, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Costabel, M.P.; Wilkinson, K.L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; McCarthy, M.; Ford, C.M.; Dokoozlian, N. Seasonal and regional variation of green aroma compounds in commercial vineyards of Vitis vinifera L. Merlot in California. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 64, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xu, X.Q.; Wang, Y.; Vanderweide, J.; Sun, R.Z.; Cheng, G.; Chen, W.; Li, S.D.; Li, S.P.; Duan, C.Q.; et al. Differential influence of timing and duration of bunch bagging on volatile organic compounds in Cabernet Sauvignon berries (Vitis vinifera L.). Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 28, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirás-Avalos, J.M.; Bouzas-Cid, Y.; Trigo-Córdoba, E.; Orriols, I.; Falqué, E. Effects of two different irrigation systems on the amino acid concentrations, volatile composition and sensory profiles of Godello musts and wines. Foods 2019, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Ikoma, Y. Effect of postharvest temperature on the muscat flavor and aroma volatile content in the berries of ‘Shine Muscat’ (Vitis labruscana Baily × V. vinifera L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 112, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, Y.; Kang, H. Melatonin is a potential target for improving post-harvest preservation of fruits and vegetables. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Guan, W.; Zhou, X.; Lao, M.; Cai, L. The physiochemical and preservation properties of anthocyanidin/chitosan nanocomposite-based edible films containing cinnamon-perilla essential oil Pickering nanoemulsions. LWT 2022, 153, 112506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salto, L.; Maoz, I.; Goldenberg, L.; Carmi, N.; Porat, R. Effects of Rainfall and Harvest Time on Postharvest Storage Performance of ‘Redson’ Fruit: A New Red Pomelo X Grapefruit Hybrid. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salifu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Sam, F.E.; Li, J.; Ma, T.Z.; Wang, J.; Han, S.Y.; Jiang, Y.M. Application of different fertilizers to cabernet sauvignon vines: Effects on grape aroma accumulation. J. Berry Res. 2022, 12, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Otmani, M.; M’Barek, A.; Coggins, C.W., Jr. GA3 and 2,4-D prolong on-tree storage of citrus in Morocco. Sci. Hortic. 1990, 44, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Miao, A.; He, X.; Li, W.; Deng, L.; Zeng, K.; Ming, J. Changes in phenolic content, composition, and antioxidant activity of blood oranges during cold and on-tree storage. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 3669–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C.; Wolstenholme, B.N. Aspects of delayed harvest of ‘Hass’ avocado (Persea americana Mill.) fruit in a cool subtropical climate. I. Fruit lipid and fatty acid accumulation. J. Hortic. Sci. 1994, 69, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 12456-2021; National Food Safety Standard-Determination of Total Acid in Food. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF.aspx/GB12456-2021 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Tu, Q.; Yuan, C. Characterization of wine volatile compounds from different regions and varieties by HS-SPME/GC-MS coupled with chemometrics. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Wen, J.; Ma, L.; Wen, H.; Li, J. Dynamic changes in norisoprenoids and phenylalanine-derived volatiles in off-vine Vidal blanc grape during late harvest. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gemert, L.J. Odour Thresholds: Compilations of Odour threshold Values in Air, Water and Other Media; Oliemans Punter: Zeist, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Ji, S.; Ji, R.; Yu, J.; Wei, D. Study on the Dynamic Evolution of Flavor Characteristics during the Fermentation Process of Chinese Northeastern Sauerkraut. Storage Process 2025. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Langen, J.; Wegmann-Herr, P.; Schmarr, H.G. Quantitative determination of α-ionone, β-ionone, and β-damascenone and enantiodifferentiation of α-ionone in wine for authenticity control using multidimensional gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 6483–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Yang, G.; Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Tan, J. Effects of delayed cultivation on fruit quality and volatile aroma components of ‘Summer Black’ and ‘Jumeigui’ grapes. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine 2021, 18–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Duan, S.; Zhao, L.; Gao, Z.; Luo, M.; Song, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, C.; Wang, S. Aroma characterization based on aromatic series analysis in table grapes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.D.; García-Cordero, J.; Suárez-Coca, D.; Ruiz del Castillo, M.L.; Blanch, G.P.; de Pascual-Teresa, S. Varietal Effect on Composition and Digestibility of Seedless Table Grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) under In Vitro Conditions. Foods 2022, 11, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Shu, N.; Wen, J.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Lu, W. Characterization of the Key Aroma Volatile Compounds in Nine Different Grape Varieties Wine by Headspace Gas Chromatography–Ion Mobility Spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS), Odor Activity Values (OAV) and Sensory Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Yang, G.; Tan, J. Analysis of 58 volatile compounds in different grape varieties using stable isotope internal standard GC-MS SIM method. Food Sci. 2023, 44, 262–269. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, F.; Wang, P.; Zhan, P.; Tian, H. Characterization of key aroma compounds in flat peach juice based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-olfactometry (GC-MS-O), odor activity value (OAV), aroma recombination, and omission experiments. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-O.; Hur, Y.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.J.; Im, D. Relationships between Instrumental and Sensory Quality Indices of Shine Muscat Grapes with Different Harvesting Times. Foods 2022, 11, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CXS 255-2007; Standard for Table Grapes. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2007.

- Yu, M.; Li, S.; Zhan, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lv, J.; Liu, Y.; Quan, X.; Xiong, J.; Qin, D.; Zhu, C. Evaluation of the Harvest Dates for Three Major Cultivars of Blue Honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) in China. Plants 2023, 12, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzolf-Panek, M.; Waśkiewicz, A. Relationship between Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and Color Parameters of Red Table Grape Skins Using Linear Ordering Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.; Giongo, L.; Cappai, F.; Kerckhoffs, H.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Hutchins, D.; East, A. Blueberry firmness—A review of the textural and mechanical properties used in quality evaluations. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 192, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-León, M.A.; Mattus-Araya, E.; Herrera, R. Molecular Events Occurring During Softening of Strawberry Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalua, C.M.; Boss, P.K. Evolution of Volatile Compounds during the Development of Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3818–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.N.; Qian, Y.H.; Liu, R.H.; Liang, T.; Ding, Y.T.; Xu, X.L.; Huang, S.; Fang, Y.L.; Ju, Y.L. Effects of Table Grape Cultivars on Fruit Quality and Aroma Components. Foods 2023, 12, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Jin, X.Q.; Feng, M.M. Evolution of volatile profile and aroma potential of table grape Hutai-8 during berry ripening. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.J.; Fang, Z.X.; Ahalya, P.; Luo, J.Q.; Gan, R.Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, P.Z. Glycosidically bound aroma precursors in fruits: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Wine Aroma Compounds in Grapes: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 55, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Ruiz, J.; Esteban-Fernández, A.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Microbial Contribution to Wine Aroma and Its Intended Use for Wine Quality Improvement. Molecules 2017, 22, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönisch, F.; Frotscher, J.; Stanitzek, S.; Rühl, E.; Wüst, M.; Bitz, O.; Schwab, W. A UDP-glucose: Monoterpenol glucosyltransferase adds to the chemical diversity of the grapevine metabolome. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.M.; Aubourg, S.; Schouwey, M.B.; Daviet, L.; Schalk, M.; Toub, O.; Lund, S.T.; Bohlmann, J. Functional annotation, genome organization and phylogeny of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera) terpene synthase gene family based on genome assembly, FLcDNA cloning, and enzyme assays. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Fan, P.G.; Jiang, J.Z.; Gao, Y.Y.; Liu, C.X.; Li, S.H.; Liang, Z.C. Evolution of volatile compounds composition during grape berry development at the germplasm level. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 293, 110669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusova, B.; Humaj, J.; Sochor, J.; Baron, M. Formation, Losses, Preservation and Recovery of Aroma Compounds in the Winemaking Process. Fermentation 2022, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Shan, B.Q.; Zhou, X.M.; Gao, W.P.; Liu, Y.R.; Zhu, B.Q.; Sun, L. Transcriptome and metabolomics integrated analysis reveals terpene synthesis genes controlling linalool synthesis in grape berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9084–9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| wpf | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| T14 | 36.90 ± 1.80 b | −2.47 ± 1.34 a | 12.46 ± 1.49 b |

| T16 | 37.17 ± 1.40 ab | −1.92 ± 0.57 b | 12.85 ± 1.30 b |

| T18 | 37.46 ± 1.96 ab | −1.28 ± 0.75 c | 13.43 ± 1.82 b |

| T20 | 37.14 ± 1.81 ab | −0.64 ± 0.52 d | 13.45 ± 1.46 b |

| T22 | 38.24 ± 1.74 a | −0.40 ± 0.61 d | 14.53 ± 1.42 a |

| T24 | 36.41 ± 1.79 b | 0.26 ± 0.54 e | 13.17 ± 1.70 b |

| wpf | Single Berry Weight/g | Longitudinal Diameter/mm | Horizontal Diameter/mm | Fruit Shape Index | Stress Tolerance/N | Soluble Solids Content (Brix) | Total Acidity (g/L) | Solid-Acid Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T14 | 10.80 ± 0.50 ab | 33.30 ± 1.47 a | 23.73 ± 1.56 a | 1.41 ± 0.11 a | 11.67 ± 1.12 c | 19.87 ± 0.37 c | 2.56 ± 0.12 a | 7.80 ± 0.52 c |

| T16 | 10.62 ± 0.37 ab | 32.45 ± 2.26 a | 23.67 ± 1.20 a | 1.37 ± 0.10 a | 11.74 ± 1.19 c | 20.89 ± 0.55 a | 2.03 ± 0.09 cd | 10.28 ± 0.30 a |

| T18 | 11.05 ± 0.07 a | 33.36 ± 1.68 a | 24.20 ± 1.06 a | 1.38 ± 0.08 a | 9.61 ± 0.73 b | 20.50 ± 0.44 ab | 2.20 ± 0.13 b | 9.36 ± 0.66 b |

| T20 | 11.13 ± 0.21 a | 33.28 ± 2.05 a | 23.80 ± 1.37 a | 1.40 ± 0.10 a | 9.45 ± 1.32 b | 20.60 ± 0.41 ab | 2.07 ± 0.09 c | 9.99 ± 0.46 a |

| T22 | 10.71 ± 0.38 ab | 32.51 ± 2.11 a | 23.50 ± 1.13 a | 1.38 ± 0.09 a | 9.92 ± 1.25 b | 20.70 ± 0.39 ab | 2.09 ± 0.08 c | 9.96 ± 0.50 a |

| T24 | 10.17 ± 0.24 b | 32.84 ± 2.19 a | 23.52 ± 1.39 a | 1.40 ± 0.09 a | 8.46 ± 2.25 a | 20.36 ± 0.41 b | 1.96 ± 0.09 d | 10.43 ± 0.48 a |

| Samples | Clean Reads | GC Content (%) | ≥Q30 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T14 | 29,937,146 | 46.27 | 93.10 |

| T16 | 29,587,311 | 45.90 | 94.49 |

| T18 | 29,687,346 | 45.99 | 94.62 |

| T20 | 22,775,664 | 45.99 | 93.71 |

| T22 | 29,033,161 | 45.65 | 94.77 |

| T24 | 23,043,260 | 46.00 | 94.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yan, M.; Lei, S.; Wang, R.; Khalil-Ur-Rehman, M.; Wang, X.; Tan, J.; Yang, G. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveal the Impact of Delayed Harvest on the Aroma Profile of ‘Shine Muscat’ Grapes. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010109

Xu Y, Dong Y, Yan M, Lei S, Wang R, Khalil-Ur-Rehman M, Wang X, Tan J, Yang G. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveal the Impact of Delayed Harvest on the Aroma Profile of ‘Shine Muscat’ Grapes. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yanshuai, Yang Dong, Meng Yan, Shumin Lei, Rong Wang, Muhammad Khalil-Ur-Rehman, Xueyan Wang, Jun Tan, and Guoshun Yang. 2026. "Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveal the Impact of Delayed Harvest on the Aroma Profile of ‘Shine Muscat’ Grapes" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010109

APA StyleXu, Y., Dong, Y., Yan, M., Lei, S., Wang, R., Khalil-Ur-Rehman, M., Wang, X., Tan, J., & Yang, G. (2026). Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveal the Impact of Delayed Harvest on the Aroma Profile of ‘Shine Muscat’ Grapes. Horticulturae, 12(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010109