Genome-Wide Identification of CmPOD Genes and Partial Functional Characterization of CmPOD52 in Lignin-Related Granulation of ‘Sanhong’ Pomelo (Citrus maxima)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Determination of Physiological Parameters

2.3. Screening and Retrieval of Candidate CmPOD Genes

2.4. Chromosome Distribution and Phylogenetic Analysis of CmPODs

2.5. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis

2.6. Cis-Acting Regulatory Element Analysis of CmPODs

2.7. Gene Duplication and Collinearity Analysis

2.8. Physicochemical Properties of CmPODs

2.9. qRT-PCR Analysis

2.10. Cloning and Subcellular Localization of CmPOD52

2.11. Transient Expression of CmPOD52

2.12. Prediction of Signal Peptides and Transmembrane Domains and Optimization of Codon Usage

2.13. Heterologous Expression of CmPOD52 in E. coli

2.14. Analysis of the Enzymatic Activity of CmPOD52

2.15. Data Analysis

3. Results

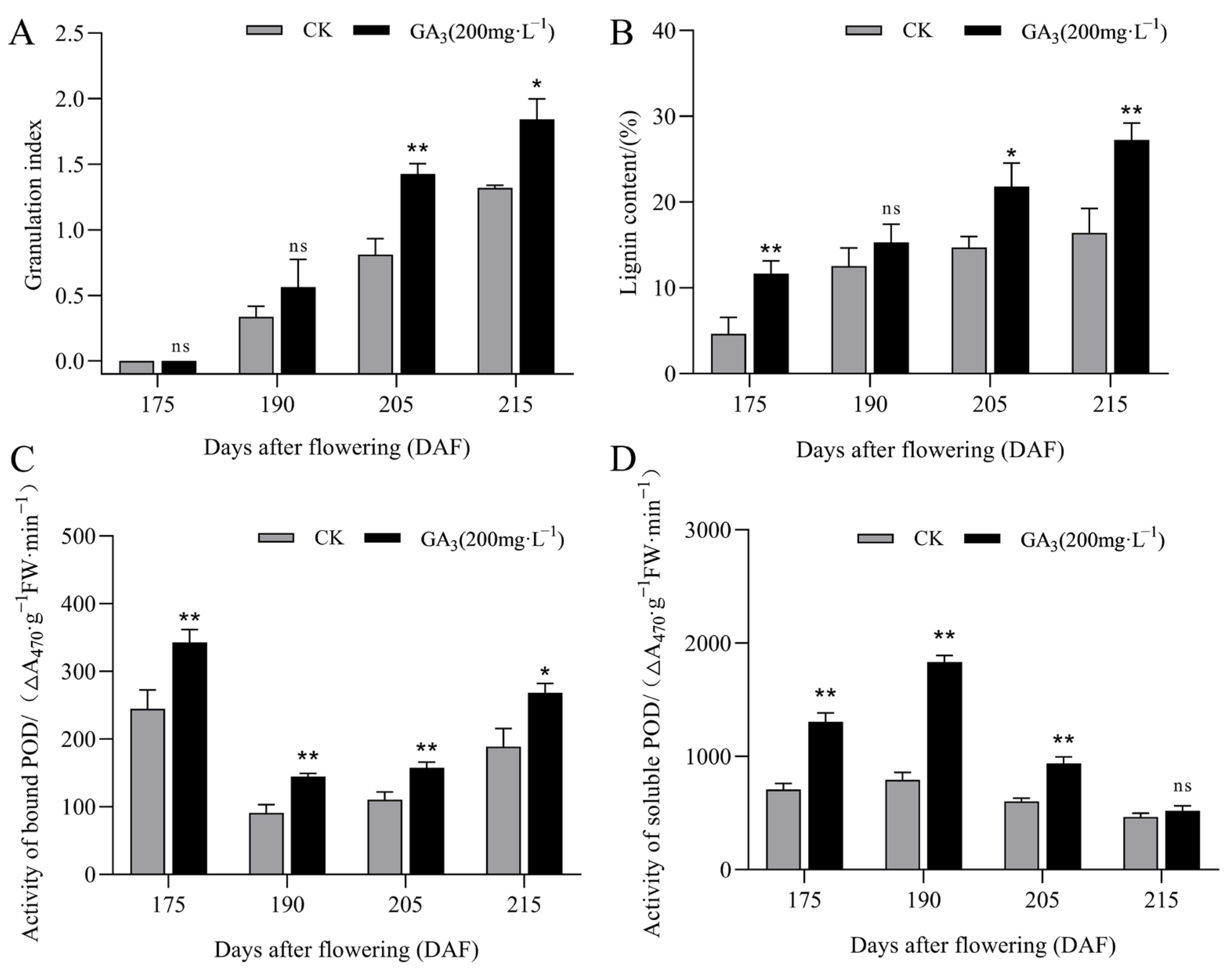

3.1. Changes in Lignin Accumulation and POD Activity During ‘Sanhong’ Pomelo Growth and Development

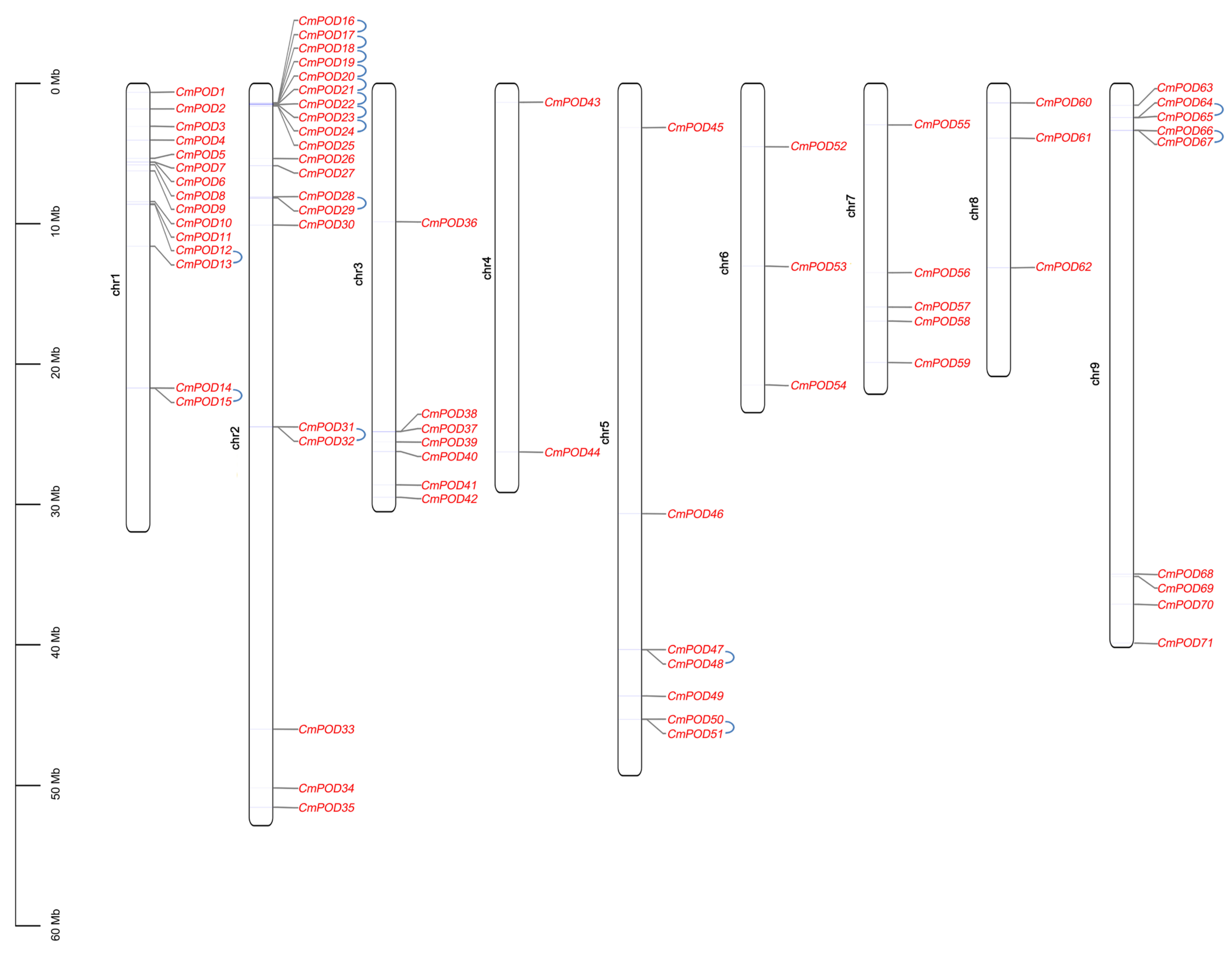

3.2. Genome-Wide Identification and Preliminary Analysis of CmPODs

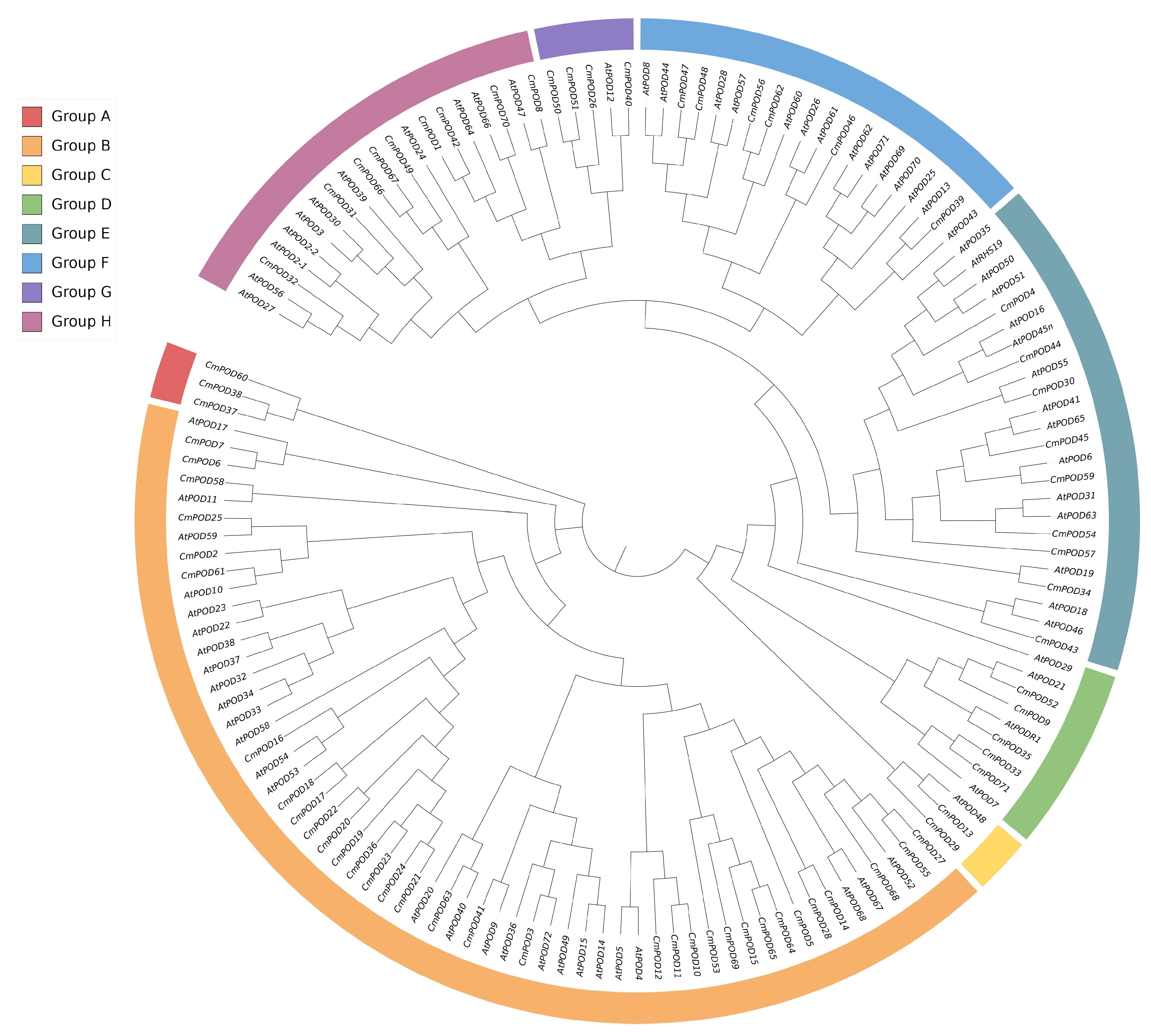

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of CmPODs

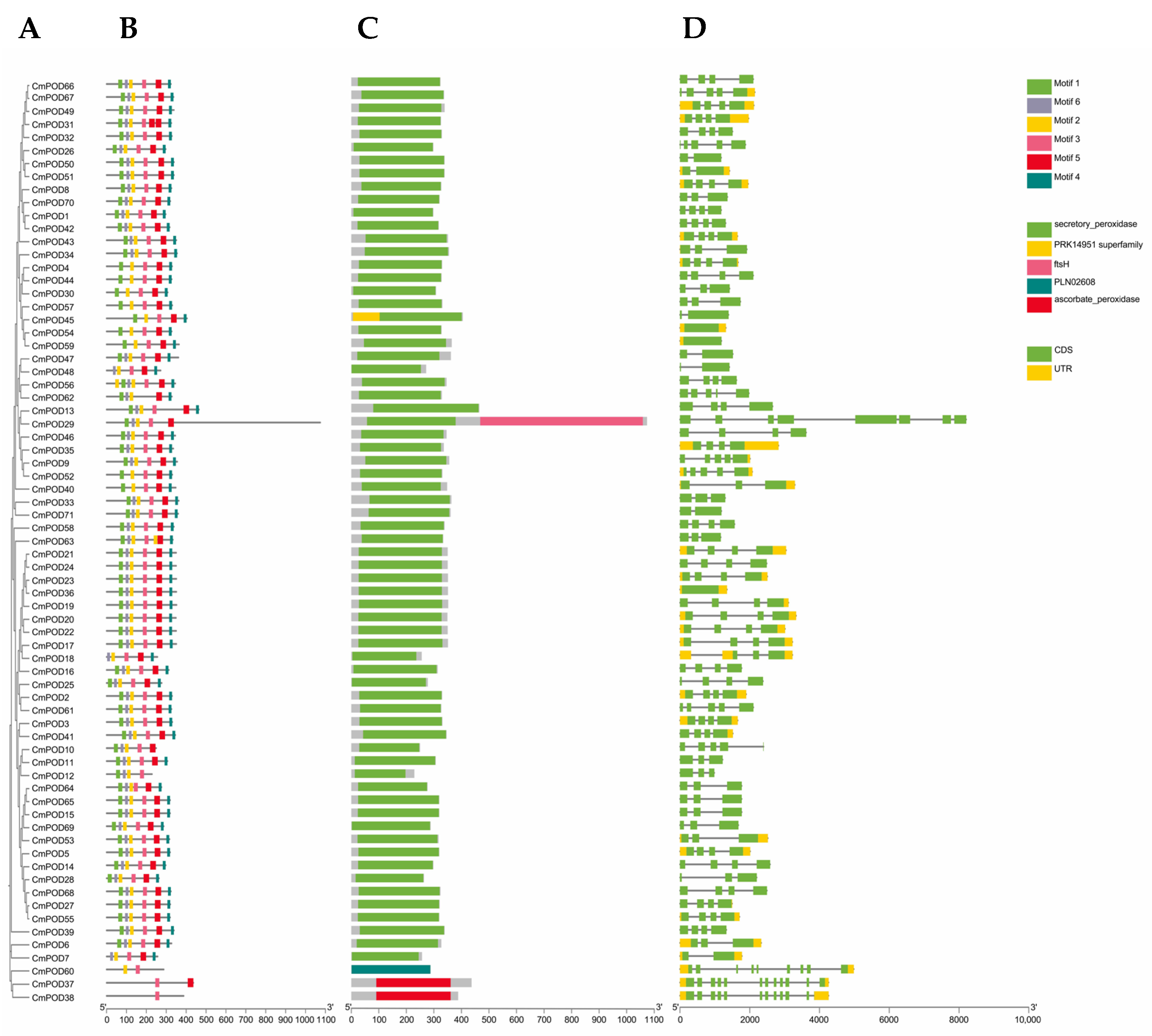

3.4. Analysis of Conserved Structures and Genetic Characteristics of CmPODs

3.5. Analysis of Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements (CAREs) in the Promoters of CmPODs

3.6. Collinearity Analysis Among CmPODs

3.7. Acquisition and Expression Analysis of BPOD Genes

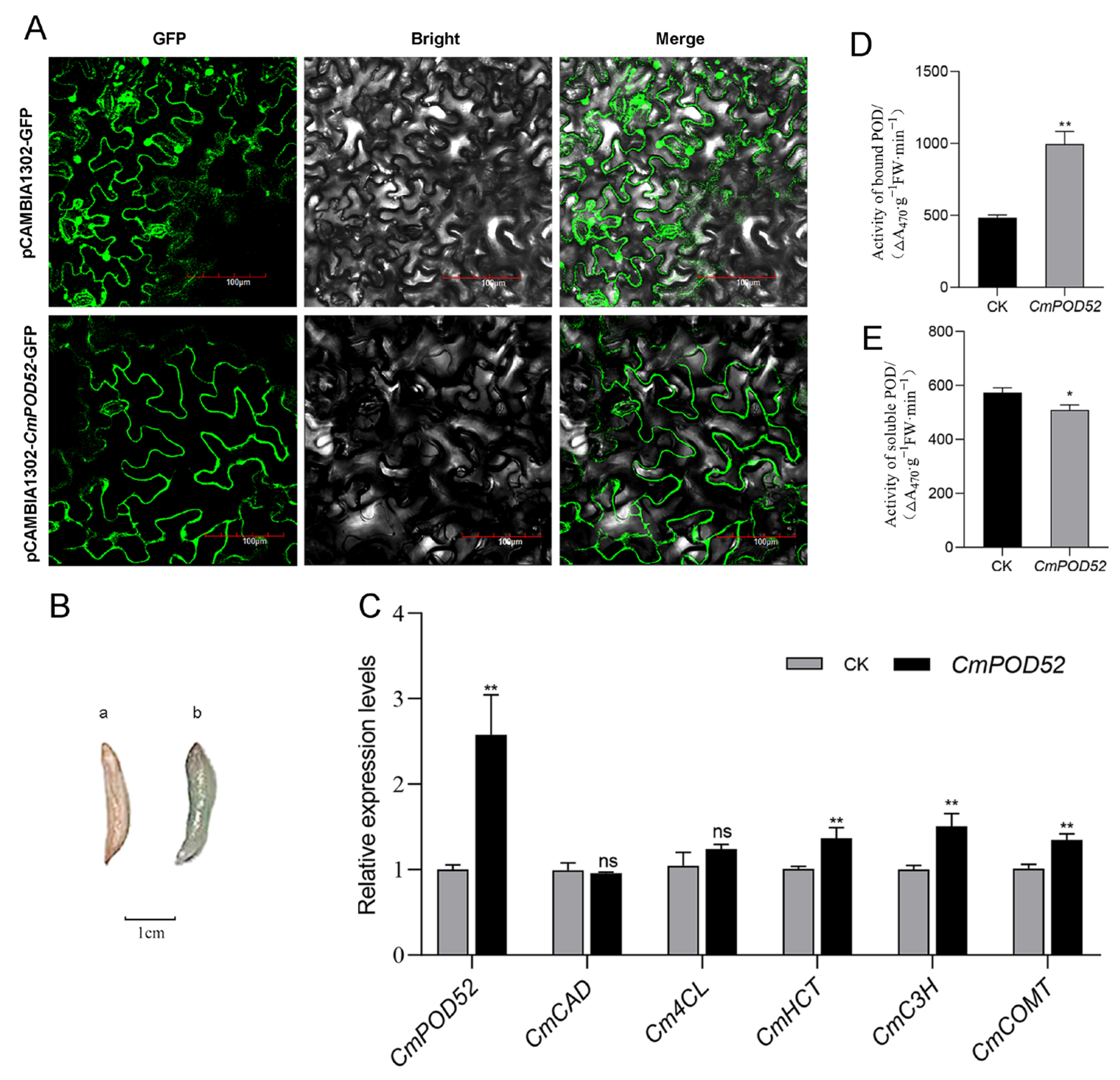

3.8. Subcellular Localization and Transient Expression Analysis of CmPOD52

3.9. Analysis of the Signal Peptide, Transmembrane Region, and Codon Optimization Results of CmPOD52

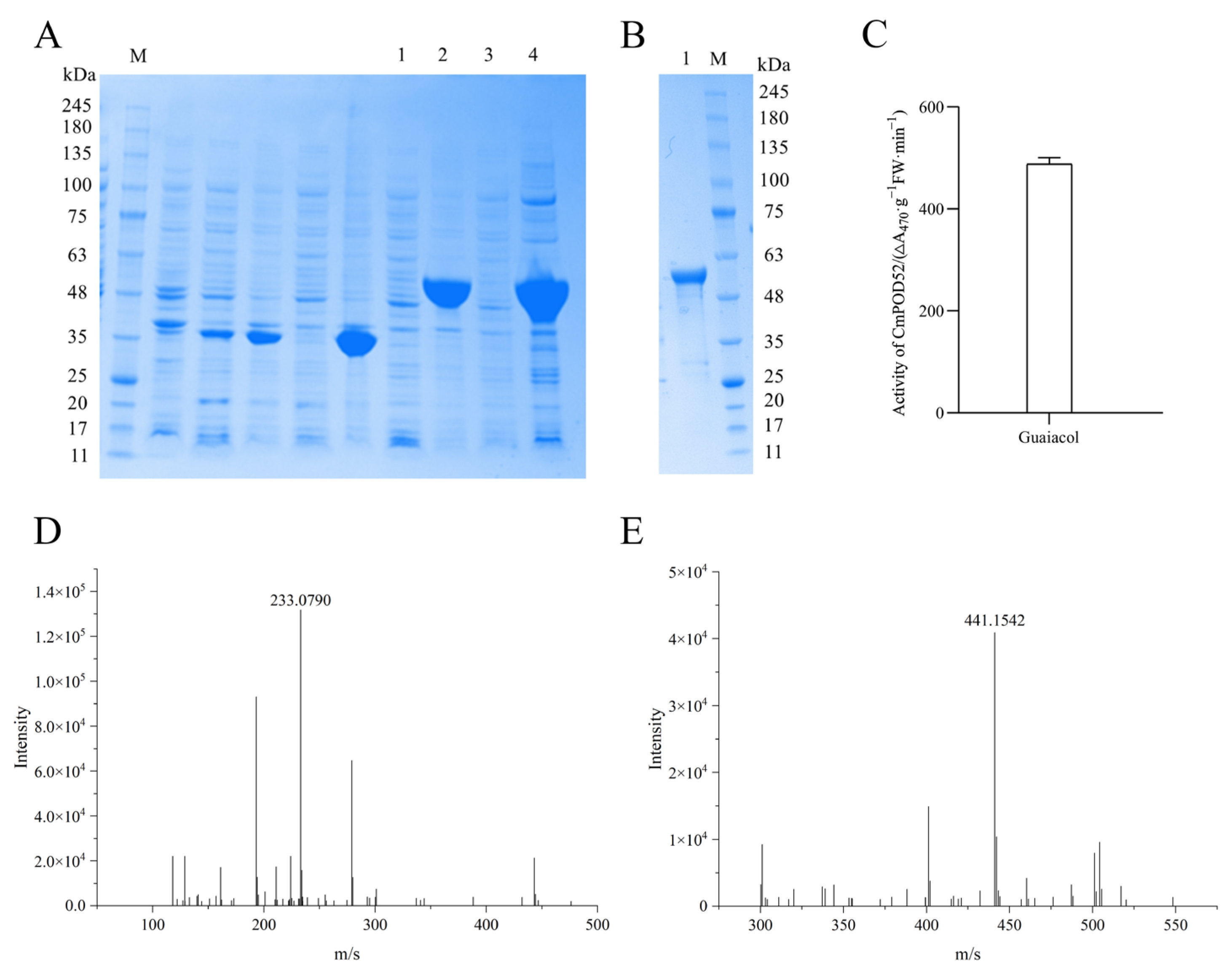

3.10. Acquisition of Recombinant CmPOD52

3.11. Functional Verification of Recombinant CmPOD52

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, K.; Yao, S. New Insights into Vesicle Granulation in Citrus grandis Revealed by Systematic Analysis of Sugar- and Acid-Related Genes and Metabolites. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 194, 112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Jiang, A.; Yang, H.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Sun, C. Integrated Physiochemical, Hormonal, and Transcriptomic Analysis Revealed the Underlying Mechanisms for Granulation in Huyou (Citrus changshanensis) Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 923443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, N.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Tan, P.; Cao, H.; Xie, Y.; Wen, B.; Gu, T.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; et al. Citrus sinensis MYB Transcription Factors CsMYB330 and CsMYB308 Regulate Fruit Juice Sac Lignification through Fine-Tuning Expression of the Cs4CL1 Gene. Plant Sci. 2018, 277, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Duan, M.; Zhang, B.; Shi, W.; Yan, S.; Li, X.; Long, C.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal That Pollination with ‘Guanxi’ Honey Pomelo Pollen Alleviates the Postharvest Fruit Granulation of ‘Crystal’ Honey Pomelo. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 230, 113831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eudes, A.; Liang, Y.; Mitra, P.; Loqué, D. Lignin Bioengineering. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 26, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikay-Benitez, D.A.; Yokoyama, Y.; Ohira, K.; Fujita, K.; Tomie, A.; Kijidani, Y.; Shigeto, J.; Tsutsumi, Y. Populus Alba Cationic Cell-Wall-Bound Peroxidase (CWPO-C) Regulates the Plant Growth and Affects Auxin Concentration in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, J.; Chen, S.; Han, X.; Qiu, W.; Lu, Z.; Zhuo, R.; Qiao, G. Comprehensive Analysis of Class III Peroxidase Genes Revealed PePRX2 Enhanced Lignin Biosynthesis and Drought Tolerance in Phyllostachys edulis. Tree Physiol. 2025, 45, tpaf008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, Q.; Tian, Z.; Huang, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, J.; Du, X.; Zhuang, M.; et al. A Multilevel Investigation to Reveal the Regulatory Mechanism of Lignin Accumulation in Juice Sac Granulation of Pomelo. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, W.; Zhao, X.; Pan, D.; Lin, H. Relationship bet ween Cell Wall Metabolism and Fruit Juicy Sac Granulation during Fruit Mature Stage of Pummelo [Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck ‘Guanxi-miyou’]. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2008, 16, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Sun, L.; Zheng, J.; Cai, C.; Wang, B.; Li, K.; Pan, T.; She, W.; Chen, G.; Pan, D. Purification, Characterization and Expression of Ionically Bound Peroxidase in Litchi Pericarp during Coloration and Maturation of Fruit. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2021, 54, 3502–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Tabayashi, A.; Iwano, M.; Shinmyo, A.; Kato, K.; Nakayama, H. Activity of the C-Terminal-Dependent Vacuolar Sorting Signal of Horseradish Peroxidase C1a Is Enhanced by Its Secondary Structure. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Pan, H.; Wu, J.; Ding, A.; Lv, S.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Li, X. Isonzyme Analysis of POD from ‘Hongroumiyou’Fruit During the Process of Juicy Sac Granulation. J. Fruit Sci. 2016, 33, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Cao, H.; He, C.; Cao, K. Effects of Gibberellin on Yield and Economic Benefit of Guanxi Pumelo. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 2010, 38, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bai, B.; Lu, X.; Li, H. A Gibberellin-Deficient Maize Mutant Exhibits Altered Plant Height, Stem Strength and Drought Tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Chen, G.; Zheng, G.; Lin, H.; She, W. Effects of Growth Regulators on Juice Sac Granulation in Pummelo Fruits. J. Fujian Agric. For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1998, 27, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, R.; Xiang, X.; Liu, W.; Fan, C. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the Class III Peroxidase Gene Family under Abiotic Stresses in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, W.; Zhao, X.; Pan, D.; Lai, Z. A study on the Changes in Isoenzymes of in the Process of ‘Guanxi’ Pummelo Juicy sac Granulation. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2008, 24, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.-X.; Tian, H.-Y.; Zeng, Y.-L.; Xue, H.; Mao, W.-T.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Chen, J.-N.; Lu, X.; Zhu, Y.; et al. The miR172a–SNB Module Orchestrates Both Induced and Adult-Plant Resistance to Multiple Diseases via MYB30-Mediated Lignin Accumulation in Rice. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Pan, H.; Wu, J.; Song, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Pan, D. Relationship Between ‘Hongroumiyou’ Fruit of Juicy Sac Granulation and Activity of Different POD. Chin. J. Trop. Crops 2016, 37, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The Protein Families Database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional Classification of Proteins via Subfamily Domain Architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for Motif Discovery and Searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a Database of Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements and a Portal to Tools for in Silico Analysis of Promoter Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A Toolkit for Detection and Evolutionary Analysis of Gene Synteny and Collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The Proteomics Server for in-Depth Protein Knowledge and Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.-J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein Localization Predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouet, P.; Courcelle, E.; Stuart, D.I.; Métoz, F. ESPript: Analysis of Multiple Sequence Alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 1999, 15, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wydro, M.; Kozubek, E.; Lehmann, P. Optimization of Transient Agrobacterium-Mediated Gene Expression System in Leaves of Nicotiana Benthamiana. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2006, 53, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Gulyás, A.; Magyar-Tábori, K.; Wang, M.-R.; Wang, Q.-C.; Dobránszki, J. In Vitro Tissue Culture of Apple and Other Malus Species: Recent Advances and Applications. Planta 2019, 249, 975–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Shi, K.; Cui, X.; Wang, S.; Jones, C.S.; Wang, Z. Overexpression of MsNAC51 from Alfalfa Confers Drought Tolerance in Tobacco. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 205, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Sønderby, C.K.; Petersen, T.N.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 5.0 Improves Signal Peptide Predictions Using Deep Neural Networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, P.; Luo, J.; Jiang, Y. Secreted Protein Prediction System Combining CJ-SPHMM, TMHMM, and PSORT. Mamm. Genome 2003, 14, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, A.; Hiller, K.; Scheer, M.; Münch, R.; Nörtemann, B.; Hempel, D.C.; Jahn, D. JCat: A Novel Tool to Adapt Codon Usage of a Target Gene to Its Potential Expression Host. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W526–W531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Wang, W.; Fan, C.; Yang, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, R.; Shen, G.; Xia, S.; Li, G. Prokaryotic Expression, Purification and Characterization of Human Cyclooxygenase-2. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.; Masi, H.A.; Patel, A.; Singh, N.K.; Joshi, C. Heterologous Expression, Purification and Single Step Efficient Refolding of Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator (Reteplase) from E. coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2024, 221, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaratskhelia, M.; Winkel, C.; Thorneley, R.N. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Class III Peroxidase Isoenzyme from Tea Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, W.; Sasaki, S.; Matsumura, S.; Mitsunaga, T.; Hirai, H.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Nishida, T. Sinapyl Alcohol-Specific Peroxidase Isoenzyme Catalyzes the Formation of the Dehydrogenative Polymer from Sinapyl Alcohol. J. Wood Sci. 2002, 48, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomar, F.; Caballero, N.; Pedreño, M.; Ros Barceló, A. H2O2 Generation during the Auto-Oxidation of Coniferyl Alcohol Drives the Oxidase Activity of a Highly Conserved Class III Peroxidase Involved in Lignin Biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 2002, 529, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika, S.-K.; Barbara, C.; Małgorzata, M.; Renata, K.; Beata, M. Phenolic Compounds in Fractionated Blackcurrant Leaf Extracts in Relation to the Biological Activity of the Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yao, S.; Deng, L.; Zeng, K. Changes in Biochemical Properties and Pectin Nanostructures of Juice Sacs during the Granulation Process of Pomelo Fruit (Citrus grandis). Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Huang, C.; Hou, J.; Zeng, K.; Yao, S. Disorder of Cell Wall Metabolism during the Transition of Citrus Juice Sacs from Healthy to Pre-Granulation and Granulation Stages: Evidence from Shiranui Mandarin. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 222, 113383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, J.; Huang, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, D.; Zeng, K.; Yao, S. Activation of the Phenylpropanoid Pathway in Citrus sinensis Collapsed Vesicles during Segment Drying Revealed by Physicochemical and Targeted Metabolomics Analysis. Food Chem. 2023, 409, 135297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, W.; Yao, S.; Yi, L.; Li, H.; Ming, J.; Zeng, K. Transcription Factor CsMYB36 Induces Wound Healing in Citrus Fruit through Sophisticated Regulation of Carbohydrate Metabolism, Suberin Biosynthesis, and Cell Wall Reinforcement. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 230, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, N.; She, W.; Guo, Z.; Pan, H.; Yu, Y.; Ye, J.; Pan, D.; Pan, T. Identification and Functional Analysis of the CgNAC043 Gene Involved in Lignin Synthesis from Citrus grandis “Sanhong”. Plants 2022, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Nie, Z.; Wan, C.; Gan, Z.; Chen, J. Suppression on Postharvest Juice Sac Granulation and Cell Wall Modification by Chitosan Treatment in Harvested Pummelo (Citrus grandis L. Osbeck) Stored at Room Temperature. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Song, J.; Feng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, N.; Li, Q.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y.; et al. Osmotic Stress-Induced Lignin Synthesis Is Regulated at Multiple Levels in Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Dai, L.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, L.; et al. A Novel ZjbZIP33-ZjPRX1 Module Positively Regulates Lignin Formation in the Jujube Fruit Stone. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4998–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Wang, Q.; Ju, H.; Tian, R.; Fu, D.; Bu, X.; Yan, R.; Xu, F.; Chen, D.; Zhang, H.; et al. The Class III Peroxidase OsPrx20 Is a Key Regulator of Stress Response and Growth in Rice. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Phuong, L.T.; Luan, M.T.; Fitrianti, A.N.; Matsui, H.; Nakagami, H.; Noutoshi, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Ichinose, Y.; Shiraishi, T.; et al. A Class III Peroxidase PRX34 Is a Component of Disease Resistance in Arabidopsis. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2019, 85, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Ge, C.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ruan, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. The Genes Related to Lignin BioSynthesis Pathway Regulate Juice Sac Granulation in Guanxi Pomelo. J. Fruit Sci. 2023, 40, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognolli, M.; Penel, C.; Greppin, H.; Simon, P. Analysis and Expression of the Class III Peroxidase Large Gene Family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 2002, 288, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Ma, L.; Meng, L.; Shang, H.; Cao, P.; Jin, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the Class III Peroxidase Gene Family in Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 916867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yuan, J.; Luo, W.; Qin, M.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.; Xie, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the Class III Peroxidase Gene Family in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 593577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, N.; Benske, A.; Betz, H.; Schuetz, M.; Samuels, A.L. Laccases and Peroxidases Co-Localize in Lignified Secondary Cell Walls throughout Stem Development. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qin, X.; Qi, J.; Dou, W.; Dunand, C.; Chen, S.; He, Y. CsPrx25, a Class III Peroxidase in Citrus sinensis, Confers Resistance to Citrus Bacterial Canker through the Maintenance of ROS Homeostasis and Cell Wall Lignification. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Guo, Y.; Shan, W.; Kuang, J.; Lu, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Luo, H.; Wei, W. Pyrazine-2-Carboxylic Acid Maintains Pummelo Quality by Modulating ROS Homeostasis through the CgWRKY31–CgPOD52 Module. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2026, 232, 113971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Cao, B.; Tang, W.; Sui, X.; Tang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Sun, B.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, H. The CaCAD1-CaPOA1 Module Positively Regulates Pepper Resistance to Cold Stress by Increasing Lignin Accumulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 290, 139979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Pan, T.; Guo, Z.; Pan, D. Specific Lignin Accumulation in Granulated Juice Sacs of Citrus maxima. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12082–12089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, F.; Pomar, F.; Pedreño, M.A.; Novo-Uzal, E. The Suppression of AtPrx52 Affects Fibers but Not Xylem Lignification in Arabidopsis by Altering the Proportion of Syringyl Units. Physiol. Plant. 2015, 154, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Pérez, F.; Vivar, T.; Pomar, F.; Pedreño, M.A.; Novo-Uzal, E. Peroxidase 4 Is Involved in Syringyl Lignin Formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 175, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, J.; Esteban Carrasco, A.; Zapata, J.M. Arabidopsis thaliana Peroxidases Involved in Lignin Biosynthesis: In silico Promoter Analysis and Hormonal Regulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Liu, B.; Zhong, R.; Chen, Y.; Fang, F.; Huang, X.; Pang, X.; Zhang, Z. Characterization of a Longan Pericarp Browning Related Peroxidase with a Focus on Its Role in Proanthocyanidin and Lignin Polymerization. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 140937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Soluble Peroxidase (SPOD) | Bound Peroxidase (BPOD) |

|---|---|---|

| Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4 (pH 6.0) | 50 mM | 50 mM |

| Guaiacol | 50 mM | 50 mM |

| H2O2 | 40 mM | 40 mM |

| Enzyme extract | 50 μL | 100 μL |

| H2O | Up to 1 mL | Up to 1 mL |

| Total volume | 1 mL | 1 mL |

| Sequence 1 | Sequence 2 | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CmPOD3 | CmPOD41 | 0.328906006 | NaN | NaN |

| CmPOD1 | CmPOD42 | 0.17740572 | 3.967992389 | 0.044709188 |

| CmPOD15 | CmPOD53 | 0.35631028 | 3.289272273 | 0.108324958 |

| CmPOD45 | CmPOD59 | 0.417279979 | 2.590938941 | 0.161053575 |

| CmPOD49 | CmPOD66 | 0.218082031 | 2.434147801 | 0.089592765 |

| Sequence 1 | Sequence 2 | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtPOD72 | CmPOD3 | 0.263806289 | 1.383257258 | 0.19071383 |

| AtPOD49 | CmPOD3 | 0.241598881 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD36 | CmPOD3 | 0.199213397 | 1.569064362 | 0.126963177 |

| AtPOD14 | CmPOD3 | 0.138183602 | 2.596366503 | 0.053221917 |

| AtPOD55 | CmPOD30 | 0.255644394 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD30 | CmPOD31 | 0.478679491 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD1 | CmPOD31 | 0.262782068 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD7 | CmPOD33 | 0.471248915 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD42 | CmPOD35 | 0.128152819 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD13 | CmPOD39 | 0.310926233 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD73 | CmPOD4 | 0.243720957 | 2.300949324 | 0.105921914 |

| AtPOD50 | CmPOD4 | 0.27287628 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD35 | CmPOD4 | 0.239055177 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD12 | CmPOD40 | 0.294622703 | 2.081542501 | 0.141540566 |

| AtPOD72 | CmPOD41 | 0.415035397 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD49 | CmPOD41 | 0.351415473 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD14 | CmPOD41 | 0.344353142 | 4.333053461 | 0.079471242 |

| AtPOD46 | CmPOD43 | 0.27355628 | 1.554852594 | 0.175937115 |

| AtPOD18 | CmPOD43 | 0.270271457 | 1.961876054 | 0.137761739 |

| AtPOD45 | CmPOD44 | 0.194246818 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD16 | CmPOD44 | 0.210746559 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD63 | CmPOD45 | 0.414631954 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD6 | CmPOD45 | 0.453305362 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD31 | CmPOD45 | 0.427908644 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD26 | CmPOD46 | 0.230426282 | 2.054661651 | 0.112148043 |

| AtPOD57 | CmPOD47 | 0.384682804 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD28 | CmPOD47 | 0.384978804 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD21 | CmPOD52 | 0.187059414 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD52 | CmPOD55 | 0.190073333 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD11 | CmPOD58 | 0.229548552 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD6 | CmPOD59 | 0.305649154 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD17 | CmPOD6 | 0.143268041 | 2.69369873 | 0.053186364 |

| AtPOD10 | CmPOD61 | 0.267982119 | NaN | NaN |

| AtPOD40 | CmPOD63 | 0.246432887 | 2.332254238 | 0.10566296 |

| AtPOD66 | CmPOD70 | 0.200961503 | 2.116198476 | 0.094963447 |

| Substrate | Activity (U/g FW) |

|---|---|

| Sinapyl alcohol | 13.67 ± 0.9 |

| Coniferyl alcohol | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lian, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; She, W.; Guo, Z.; Pan, H.; Pan, T. Genome-Wide Identification of CmPOD Genes and Partial Functional Characterization of CmPOD52 in Lignin-Related Granulation of ‘Sanhong’ Pomelo (Citrus maxima). Horticulturae 2026, 12, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010106

Liu Y, Wang X, Lian R, Zhao Y, Zhou Y, Yu Y, She W, Guo Z, Pan H, Pan T. Genome-Wide Identification of CmPOD Genes and Partial Functional Characterization of CmPOD52 in Lignin-Related Granulation of ‘Sanhong’ Pomelo (Citrus maxima). Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yunxuan, Xinjia Wang, Rong Lian, Yan Zhao, Yurong Zhou, Yuan Yu, Wenqin She, Zhixiong Guo, Heli Pan, and Tengfei Pan. 2026. "Genome-Wide Identification of CmPOD Genes and Partial Functional Characterization of CmPOD52 in Lignin-Related Granulation of ‘Sanhong’ Pomelo (Citrus maxima)" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010106

APA StyleLiu, Y., Wang, X., Lian, R., Zhao, Y., Zhou, Y., Yu, Y., She, W., Guo, Z., Pan, H., & Pan, T. (2026). Genome-Wide Identification of CmPOD Genes and Partial Functional Characterization of CmPOD52 in Lignin-Related Granulation of ‘Sanhong’ Pomelo (Citrus maxima). Horticulturae, 12(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010106