1. Introduction

Improving total factor productivity (TFP)—commonly defined as the efficiency with which all production inputs (e.g., labor, land, and capital) are jointly transformed into agricultural output—is widely recognized as a central pathway toward sustainable agricultural development, especially as contemporary agricultural systems confront mounting natural and socio-economic constraints [

1]. These constraints include a rising food demand driven by population growth, increasing climatic risks, shrinking arable land, and an aging rural labor force [

2]. Under such pressures, enhancing the efficiency with which farmers allocate labor, land, and capital has become essential for sustaining agricultural output and rural livelihoods.

In apple production, efficiency improvement is particularly urgent. Apple farming has long relied on high-intensity chemical inputs, especially pesticides and fertilizers, to stabilize yields and control pests [

3,

4]. Although this strategy has supported production in the short run, it has also generated growing challenges, including higher production costs, pesticide residue risks, and ecological externalities such as soil and water contamination [

3,

5,

6]. These concerns have stimulated demand for more environmentally sound pest-management approaches that can maintain yield stability while reducing the dependence on chemical pesticides [

7].

In this study, green pest control technologies (GPCTs) refer to a suite of environment-friendly pest-management techniques, including ecological regulation, biological control (e.g., biopesticides and the use of natural enemies), physico-chemical inducement/trapping (e.g., insecticidal lamps and color/pheromone traps), and scientific pesticide-use technologies (i.e., judicious and targeted pesticide application when necessary) [

8]. Importantly, these components may differ in cost, complexity, and effectiveness; our empirical analysis does not impose that each component contributes equally. Instead, we estimate the average efficiency effect of any GPCT adoption relative to non-adoption, which is policy-relevant given that local extension programs typically promote these practices as a package. In addition, Integrated pest management (IPM) is an ecosystem-based pest-management strategy that integrates multiple tactics (biological, cultural, physical, and chemical measures) based on monitoring and decision-making rules, rather than a single control method; in China, green control technologies are widely promoted and implemented as important practices aligned with the IPM framework [

9]. By replacing or reducing chemical pesticide use and improving the precision and effectiveness of pest and disease management, GPCTs may raise output quality, lower control costs, and strengthen ecological sustainability [

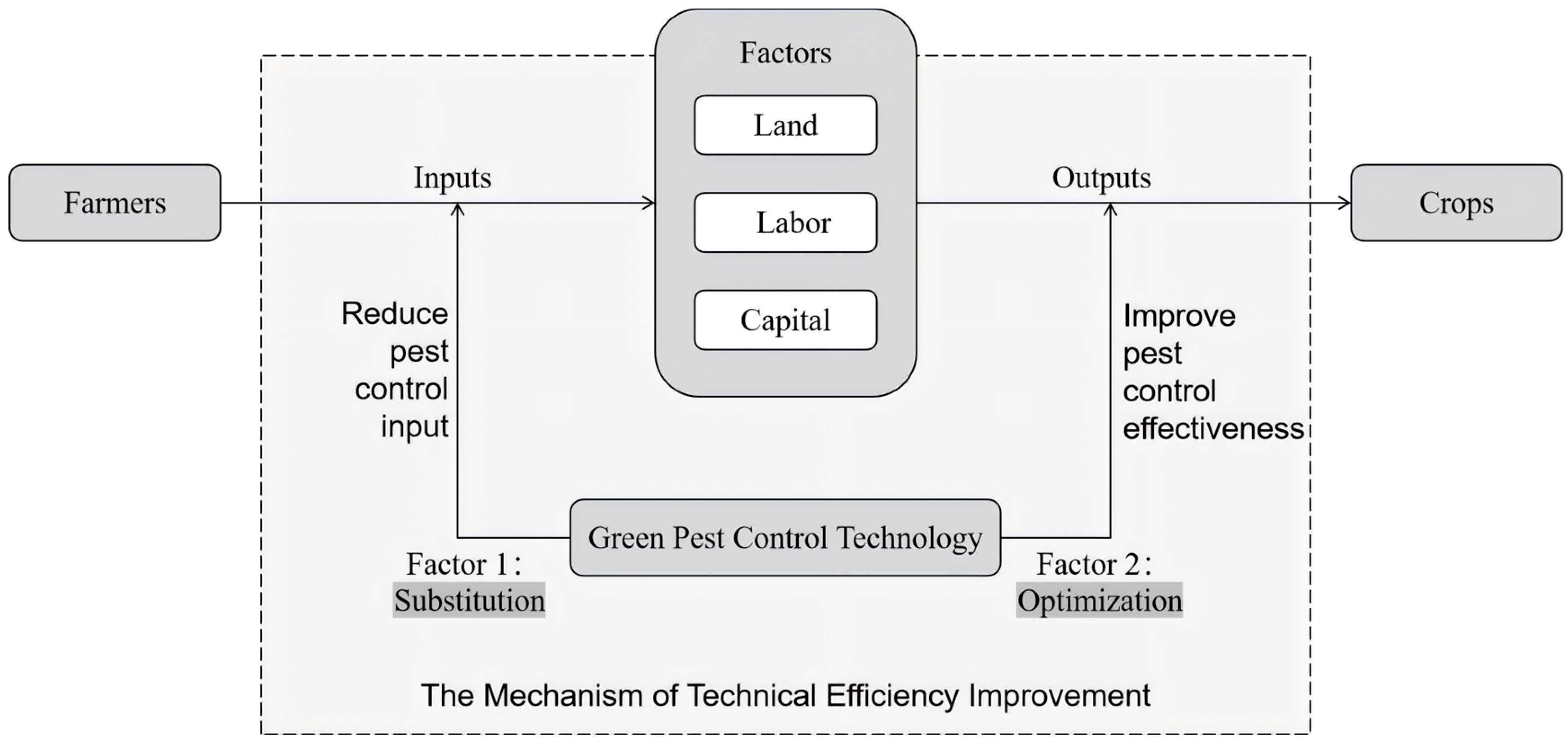

10]. From an economic perspective, these technologies are expected to impact agricultural performance not only through yield or income effects but also through changes in the efficiency of input use, thereby potentially improving farmers’ technical efficiency [

11].

Internationally, the promotion of green agricultural technologies has been accelerated, supported by policy instruments such as the EU’s agri-environmental schemes and U.S. environmental incentive programs [

12]. However, in many developing regions, adoption remains constrained by limited access to information, capital, and technical services [

13,

14]. As the world’s largest apple producer, China has placed GPCT promotion at the core of its green agricultural transformation. Policies emphasizing pesticide reduction and ecological production are being implemented nationwide [

15], but empirical evidence on whether GPCT adoption improves farmers’ technical efficiency—and for whom such benefits are the most significant—remains limited [

16].

Existing research on green agricultural technologies has primarily focused on adoption determinants and their impacts on yields or household income [

17]. However, relatively little attention has been paid to how GPCT adoption affects farmers’ technical efficiency, a crucial component of TFP and long-term sustainability [

18]. Moreover, because adoption decisions are endogenous and potentially subject to both observable and unobservable selection, conventional estimation strategies may lead to biased conclusions [

19]. In addition, farmers’ resource endowments (e.g., income levels) may shape both adoption capacity and efficiency gains, implying heterogeneous effects that have not been sufficiently explored [

20]. From a sustainability and productivity perspective, however, focusing solely on yield or income may overlook whether green pest-control transitions improve the efficiency of input use, which ultimately underpins TFP growth.

To address these gaps, this study investigates the impact of GPCT adoption on the technical efficiency of apple farmers in Shandong Province, China. Using micro-survey data collected in 2022 from major apple-producing counties in Yantai and Linyi, we first estimate farmers’ technical efficiency through a stochastic frontier analysis method (SFA) framework [

21]. We then employ an endogenous switching regression model (ESR) to correct for endogeneity and self-selection in adoption, enabling a credible estimation of the causal efficiency effect of GPCT adoption [

19]. Furthermore, we examine heterogeneity across income groups to identify whether GPCTs generate larger efficiency gains for resource-constrained farmers.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. While existing studies on IPM/green pest-control adoption in China have largely focused on adoption determinants and outcome indicators such as pesticide reduction, yields, or household income, our study advances the evidence base in both conceptual and methodological terms. First, we shift the evaluation focus to technical efficiency, a core component of TFP and a key metric for long-run sustainable intensification, thereby assessing whether GPCT adoption improves the efficiency with which multiple inputs are converted into output rather than only changing output or income levels. Second, by integrating SFA for efficiency measurement with an ESR model framework, we correct for both observable and unobservable selection in adoption decisions and provide more credible estimates of the causal efficiency effect. Third, we document income-based heterogeneity in efficiency gains, highlighting distributional implications of GPCT diffusion and informing more targeted and inclusive policy design.

3. Model Construction and Variable Selection

3.1. Model Construction

3.1.1. Estimating Farmers’ Technical Efficiency: Stochastic Frontier Analysis Method

There are various methods of measuring agricultural production efficiency, mainly including single-factor and total factor productivity [

32]. Single-factor productivity refers to the ratio of output level to the input quantity of a particular production factor [

33], and common types include labor and land productivity. This approach assumes that farmers are operating in an optimal factor market, where there are no efficiency losses during production. In contrast, total factor productivity refers to the total efficiency level at which inputs are converted into outputs during agricultural production, excluding the impact of other factors on output [

32,

33]. Among these, farmers’ technical efficiency is an essential component of total factor productivity. It measures the efficiency of resource allocation from the perspective of input–output, reflecting the ratio of actual output to optimal output when the production method and input factors remain unchanged. This measurement incorporates the existence of efficiency losses in agricultural production, thus better reflecting the actual agricultural production of farmers. On this basis, this study selects farmers’ technical efficiency as an indicator of agricultural production efficiency [

34].

There are two main categories of methods to quantify farmers’ technical efficiency: non-parametric methods, such as data envelopment analysis (DEA), and parametric methods, such as the stochastic frontier analysis method (SFA) [

32]. Compared to the DEA method, the SFA method has two main advantages: First, it allows the error term to be divided into two parts: an inefficiency term and a random error term, enabling an accurate description of agricultural production inputs [

21]. Second, the SFA method estimates a stochastic production frontier, which can effectively avoid the impact of natural disasters and weather changes on technical efficiency estimation [

35]. This study therefore used the SFA method to measure farmers’ technical efficiency.

The SFA method requires setting a functional relationship between inputs and outputs [

36]. The commonly used functional forms are the transcendental logarithmic production function and the Cobb–Douglas (C–D) production function [

37]. Compared to the transcendental logarithmic production function, the C–D production function is more concise and its economic meaning is easier to understand. Moreover, the focus of this section is on measuring farmers’ technical efficiency, not on examining the form of the production function. Based on Christensen et al. [

37], the C–D production function yields better results than other functional forms. In addition to the Cobb–Douglas (C–D) frontier, we also estimated a translog specification as a flexible alternative. Since the C–D model was nested within the translog model, we formally tested the joint null hypothesis that the second-order and interaction terms in the translog function were jointly equal to zero (i.e., the C–D restrictions). The test results suggested that the translog form did not yield a statistically significant improvement in model fit relative to the C–D form. We therefore retained the C–D production frontier as the baseline for technical-efficiency estimation. Nevertheless, we note that functional-form choice may affect the level and dispersion of estimated efficiency; reassuringly, our qualitative conclusions regarding the efficiency effect of GPCT adoption are robust to using the alternative functional form.

This study therefore adopted the C–D production function form to measure farmers’ technical efficiency. Following Battese et al. [

36], the C–D form of the SFA method was specified as follows:

In Equation (1),

represents the apple output of the

farmer, while

,

, and

are the labor, land, and capital input factors, respectively.

,

,

, and

are the parameters to be estimated, and

is the random error term, assumed to follow a symmetric normal distribution. The inefficiency term

follows an exponential distribution with a mean of

. The stochastic frontier production function was estimated using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), and the technical efficiency of farmers could be calculated as follows:

where

is the expected output of the farmer and

is the maximum expected output. The technical efficiency of farmers was defined as the ratio of the actual output to the maximum output. The value of technical efficiency ranged from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating that farmers were near maximum efficiency and values closer to 0 indicating greater inefficiency.

Technical efficiency measures the management and production efficiency of farmers [

32]. Based on the existing literature [

38,

39] and the theory of farmer behavior, this study selected factors such as the adoption of green pest control technologies, the characteristics of production decision-makers, household characteristics, and agricultural production characteristics as factors influencing agricultural production technical efficiency. To examine the impact of green pest control technology adoption on farmers’ technical efficiency, the following preliminary model was proposed:

In Equation (3), represents whether the farmer adopts green pest control technology, and is a set of other factors influencing technical efficiency. The random error term accounts for unobserved factors.

3.1.2. Treatment Effect of Green Pest Control Technology Adoption on Farmers’ Technical Efficiency: Endogenous Switching Regression Model

While the SFA method estimates farmers’ technical efficiency, this section further analyzes the effect of green pest control technology adoption on farmers’ technical efficiency. In practice, apple farmers make the decision to adopt green pest control technology, and the choice of treatment and control groups is not random, which may introduce selection bias. Existing studies often use propensity score matching (PSM) methods to assess the impact of treatment variables on farmers’ technical efficiency [

40,

41,

42]. However, PSM is a non-parametric method and can only address selection bias caused by observable factors. The endogenous switching regression model (ESR) can address both observable and unobservable factors that may lead to selection bias [

43]. Based on existing research [

44], this study therefore selects farmers’ technical efficiency as the outcome variable and green pest control technology adoption as the treatment variable, using the ESR model to empirically test the impact of green pest control technology adoption on farmers’ technical efficiency.

The ESR model regression process consists of two steps: first, selection equation regression, which reflects the relationship between various variables such as personal characteristics, household production management, and the decision to adopt green pest control technology [

43]; second, outcome equation regression, which estimates the impact of green pest control technology adoption on farmers’ technical efficiency, controlling for endogeneity [

19].

The first-stage selection equation and the second-stage outcome equation were as follows.

Outcome Equation for Treatment Group:

Outcome Equation for Control Group:

In the selection equation, is a binary variable that indicates the decision to adopt green pest control technology, determined by the utility gained from adopting versus not adopting. The random error terms and were assumed to be normally distributed. The outcome equations represented the technical efficiency of farmers in the treatment and control groups. The model used the inverse Mills ratio from the selection equation to address selection bias caused by unobserved factors.

The ESR model was estimated using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), which jointly estimates the selection and outcome equations. The average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) and the average treatment effect on the untreated (ATU) could be calculated using the following expressions (7) and (8):

The ESR model allowed us to address potential selection bias and provide more accurate estimates of the treatment effect of GPCT adoption on technical efficiency.

3.2. Data Source

The micro-level data for this study was collected in 2022 through a questionnaire survey targeting apple farmers in the primary apple-producing regions around the Bohai Sea. The surveyed areas included Muping District, Penglai District, and Qixia City in Yantai, Shandong Province, as well as Mengyin County and Yishui County in Linyi. The survey employed one-on-one questionnaire interviews and utilized stratified sampling to account for regional economic development levels, agricultural production scales, and geographical characteristics.

In each county or district, two to three townships were selected, followed by the selection of two to three administrative villages within each township. Within each village, 10 to 20 apple farmers were randomly chosen for one-on-one interviews and questionnaire surveys. A total of 475 questionnaires were distributed, of which 409 were valid, yielding an effective response rate of 86.11%. Specifically, a questionnaire was considered valid if it (i) was fully completed for the core modules, (ii) contained non-missing values for the key variables required for the SFA method and ESR model estimations (output, labor input, land input, pesticide and fertilizer input, other capital input, GPCT adoption indicator, the instrumental variable, and main covariates), and (iii) passed basic logical and consistency checks (e.g., non-negative costs and output; positive cultivated area; no internally contradictory responses). Questionnaires failing any of these criteria were excluded.

In the surveyed apple orchards, farmers’ GPCT was implemented not only through physical/ecological measures (e.g., trapping and monitoring-based decisions) but also through the use of biopesticides and agricultural antibiotics. Based on field interviews and farmers’ reports, commonly used products in the biological/green control package included abamectin 1.8% EC (such as Shandong Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Jinan, China), polyoxin B 10% WP, locally referred to as duokangmeisu (such as Shandong Lvba Pesticide Co., Ltd., Jinan, Shandong, China), and jinggangmycin/validamycin A 5% AS (such as Shandong Huayang Technology Co., Ltd., Tai’an, China). In addition, some adopters applied selective insect growth regulators, such as hexaflumuron 5% EC (Shandong Zibo Lüjing Pesticide Co., Ltd., Zibo, China), a benzoylurea chitin-synthesis inhibitor, as complementary tools under IPM-aligned management.

To address application intensity, we also collected the number of pesticide spray applications per year. Across 409 households, the median number of applications was 8 (interquartile range: 8–10), with the 95th percentile at 13 and the 99th percentile at 15 applications.

Table 1 reports the results of a two-sample

t-test with equal variances for the number of pesticide spray applications per year. Group Non-Adopters refers to non-adopters of GPCT and Group Adopters refers to adopters of GPCT. The

p-value from the two-tailed

t-test was 0.568, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

3.3. Variable Selection

To capture the relevant factors affecting farmers’ technical efficiency and the adoption of GPCTs, we selected the following key variables:

3.3.1. Input and Output Variables

The output variable was the total income from apple cultivation, calculated by multiplying the output level of different apple varieties produced by the apple farmers by their respective sales prices. The labor input variable was the total labor input in all stages of apple cultivation, including both family labor and hired labor. The land input variable refers to the total area of land used for apple cultivation. The pesticide and fertilizer capital input variable was the total cost of pesticides and fertilizers used in the apple cultivation process. The non-pesticide fertilizer capital input variable represented the total production costs, including expenses for orchard management tools, grafting and scion costs, bagging and harvesting labor costs, refrigeration, water, electricity, and irrigation costs.

It is worth noting that the input–output variables were primarily used to measure the technical efficiency of apple farmers. In this study, we used the Cobb–Douglas (C–D) production function form in the stochastic frontier production function model to calculate efficiency, and the input–output variables were expressed in logarithmic form in the model. Therefore, the variable definitions for input–output also adopted logarithmic forms.

As a measure of pesticide input intensity, we collected data on the number of pesticide spray applications per year across the surveyed farms. A two-sample

t-test comparing the spray application frequencies between adopters and non-adopters of GPCT revealed no significant difference (

p-value = 0.568) between the two groups. The average number of applications for non-adopters was 10.33, while for adopters it was 9.50 (

Table 1). This indicates that while GPCT adoption might be linked to a potential reduction in pesticide spray intensity, the difference was not statistically significant in our sample.

3.3.2. Outcome Variable: Farmers’ Technical Efficiency

This variable was derived from the estimation of the C–D production function form using the stochastic frontier production function model.

3.3.3. Treatment Variable: Green Pest Control Technology Adoption Decision

Our GPCT adoption variable was defined as a binary indicator equal to one if a farmer adopted at least one practice from the GPCT set during the production season. As a result, the ESR-based ATT/ATU estimates needed to be interpreted as the average technical-efficiency effect of ‘any GPCT adoption’ versus none. If returns differed across GPCT components (or across adoption intensity), the estimated effect represented a weighted average across the observed adoption mix and could mask component-specific impacts; this heterogeneity was not separately identified in the current framework and is discussed as a limitation and a direction for future research.

While this binary specification is parsimonious and closely aligned with policy discourse on ‘GPCT adoption’ as initial uptake, it does not capture heterogeneity in adoption intensity (e.g., the number of GPCT components adopted, usage frequency, or the magnitude of input reallocation) or specific technology bundles. Constructing an intensity-based measure or composite index would require comparable cardinal information across heterogeneous practices and a defensible weighting scheme, which was not directly available from our survey and could have introduced additional measurement error and arbitrariness. We therefore interpreted our estimates as the average effect of any GPCT adoption versus none.

As a diagnostic for the exclusion restriction, we additionally included the distance variable in the technical-efficiency outcome equations; the coefficient was statistically insignificant (p > 0.10), and the estimated efficiency effects of GPCT adoption were virtually unchanged.

3.3.4. Control Variables

Based on the existing literature [

24,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], the following control variables were selected for this study:

- (1)

Personal characteristics of the surveyed farmers, including variables such as age, education level, years of apple cultivation experience, and the square of years of cultivation.

- (2)

Household production and management characteristics, including variables such as the number of agricultural training sessions attended, per capita apple farming area, and number of people involved in farming.

- (3)

Orchard conditions, including variables such as the fragmentation degree of the orchard and soil quality.

Additionally, to exclude the interference of regional characteristics, economic levels, and other factors, the model also included a set of regional dummy variables.

3.3.5. Instrumental Variables

To address potential endogeneity issues, such as measurement errors or omitted variables in the empirical regression process, instrumental variables were required. This study selected the variable “distance from the residence to the nearest green production technology promotion location” as the instrumental variable. This variable significantly influenced apple farmers’ decision to adopt green pest control technologies, but it was exogenous to farmers’ technical efficiency, making it suitable as an instrumental variable for the model.

The underlying intuition was that proximity increases farmers’ exposure to GPCT demonstrations and trainings and lowers travel and participation costs, which affects the adoption decision. The exclusion restriction required that, conditional on observed household characteristics, farm inputs, and location controls, this distance measure did not directly influence farmers’ technical efficiency except through its impact on GPCT adoption. Potential direct channels include broader access to markets, infrastructure, and general extension services. To address these concerns, we controlled for location-related factors capturing market/extension access (e.g., distance to township/county center, road/infrastructure conditions, and village characteristics where available) and conducted a robustness check by allowing the distance variable to enter the outcome equations; it was statistically insignificant and the estimated ATT/ATU results remained qualitatively unchanged.

3.4. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 2 reports the variables used in the empirical analysis of this study, along with their definitions and descriptive statistics. Analyzing the contents of the table reveals that 223 of the respondents, approximately 54.52% of the total sample, adopted green pest control technologies in their apple cultivation process, while the remaining 186 respondents, or approximately 45.48%, did not adopt these technologies. The mean of the farmers’ technical efficiency was 0.70, indicating a 30% efficiency loss. The average age of the respondents was 55.23 years, with an average education level of 8.11 years. The average years of apple cultivation experience was 21.74 years. The mean distance between the respondents’ residences and the nearest green technology promotion location was 6.07 km.

6. Conclusions

GPCT adoption significantly improves technical efficiency, with non-adopters potentially experiencing an 18.2% increase in efficiency if they adopt these technologies. Conversely, adopters would face a 3.9% decline in efficiency if they discontinued their use. Additionally, the efficiency gains from GPCT adoption are greater for lower-income farmers, suggesting that these technologies can help reduce efficiency disparities among different income groups.

These findings highlight the importance of supporting the adoption of GPCTs, particularly for resource-constrained farmers, through targeted policies such as financial assistance, subsidies, and enhanced access to agricultural extension services. These measures can help overcome barriers to adoption and foster sustainable agricultural practices. Policymakers should also consider market-driven incentives, such as premium prices for sustainably produced apples and certification schemes, to further encourage adoption.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is limited by its focus on apple farmers in Shandong Province, China. Future research could expand to other regions and incorporate broader ecological and health impact measures, as well as explore the psychological and behavioral factors influencing adoption decisions.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that GPCT adoption can enhance technical efficiency and promote sustainable agricultural practices, especially among lower-income farmers. Policymakers should therefore prioritize promoting these technologies to achieve both economic and environmental sustainability goals.

Beyond reiterating the estimated treatment effects, our results have broader implications for sustainable horticulture. In perennial orchard systems characterized by high pest and disease pressure, GPCT adoption can contribute to sustainable intensification by improving the efficiency with which labor, land, and purchased inputs are transformed into output, while potentially reducing the environmental footprint associated with conventional chemical control. The finding that non-adopters would experience sizable counterfactual efficiency gains also implies substantial unrealized productivity potential, highlighting the importance of lowering learning and information barriers in the diffusion stage.

Although the empirical evidence is based on apple producers in China, the efficiency-enhancing role of knowledge-intensive pest-management practices may extend to other horticultural crops and regions where similar constraints hold. At the same time, external validity likely depends on complementary conditions such as the availability of GPCT inputs, the capacity of local extension systems, and farmers’ access to training and output markets. Given that our analysis uses a binary adoption measure and cross-sectional data, future research combining multi-region panel datasets with component-level intensity measures could examine longer-run dynamics, identify dose–response relationships, and determine which GPCT bundles deliver the largest and most inclusive efficiency gains.