Biotechnologies for Promoting Germplasm Resource Utilization and Preservation of the Coconut and Important Palms

Abstract

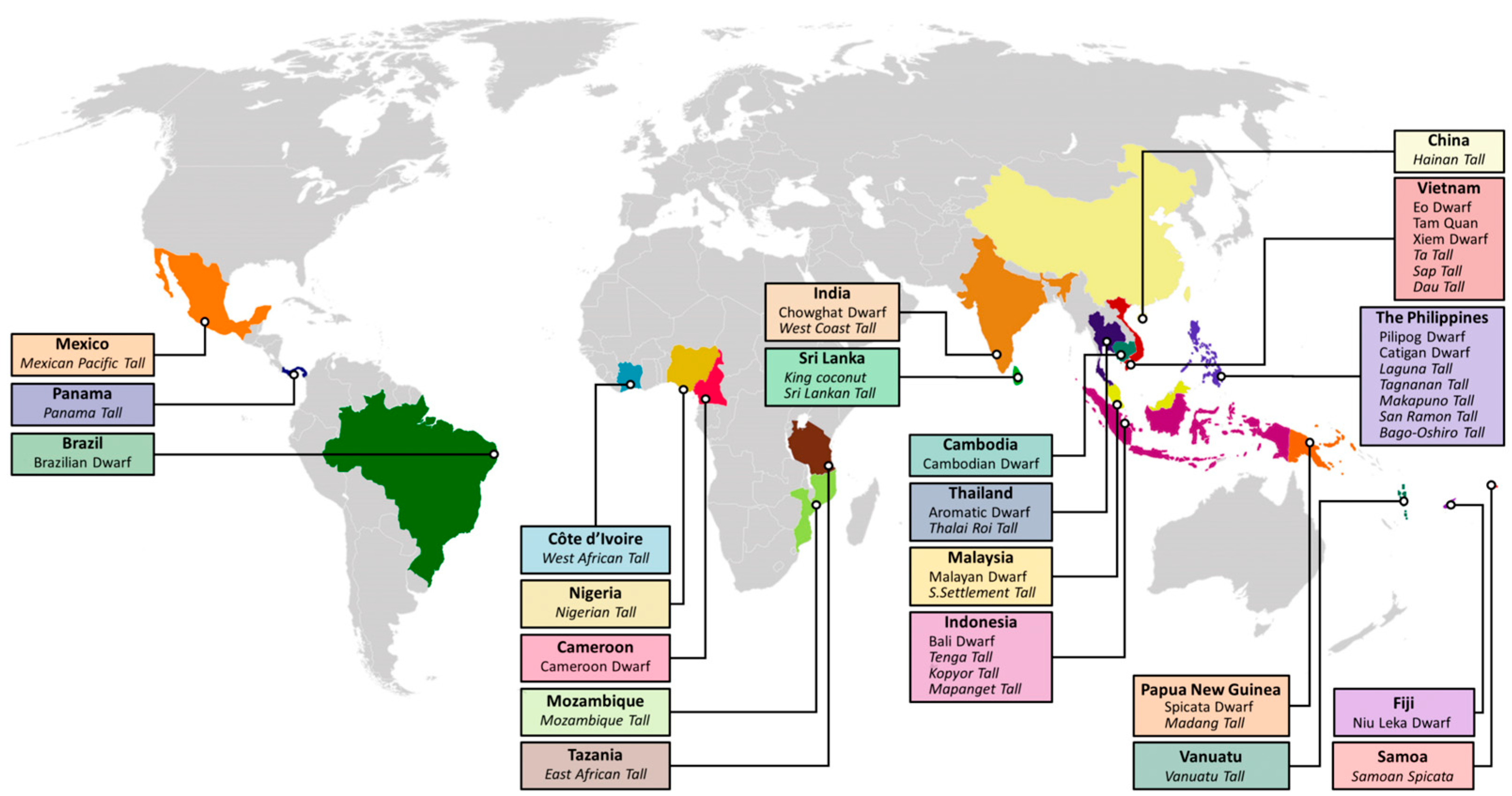

1. The Distribution of Important Coconut Germplasms Worldwide

2. The Domestication and Diversification History of the Coconut

| Germplasm Type | Key Characteristics | Breeding Advantages Breeding | Limitations | Application Prospects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tall Coconut | High genetic diversity, strong adaptability | Provides broad genetic base, strong stress tolerance | Long growth cycle, low breeding efficiency | As breeding parent providing superior genes | [27,32,33] |

| Dwarf Coconut | Early fruiting, self-pollinating, uniform traits | Shortens breeding cycle, facilitates variety purification | Narrow genetic base, environmental sensitivity | Direct cultivation and breeding material | [27,32,34] |

| Makapuno Type | Gelatinous endosperm, unique texture | Development of high-value products | Difficult to propagate naturally | Commercial development through embryo rescue | [8,10,35] |

| Aromatic Coconut | Unique flavor, high market demand | Enhances commercial value | Relatively low yield | Premium fresh market, specialty beverages | [8,36,37] |

3. Identification and Evaluation of Coconut Germplasm Using Advanced Genomic Research Tools

4. Importance of Coconut Germplasm Exchange and Conservation

5. Methods for Coconut Germplasm Identification and Exchange

5.1. Traditional Transportation of Coconut Nuts/Seedlings and Its Risks

5.2. Embryo Culture/Fresh Embryo Exchange Techniques or Similar Techniques

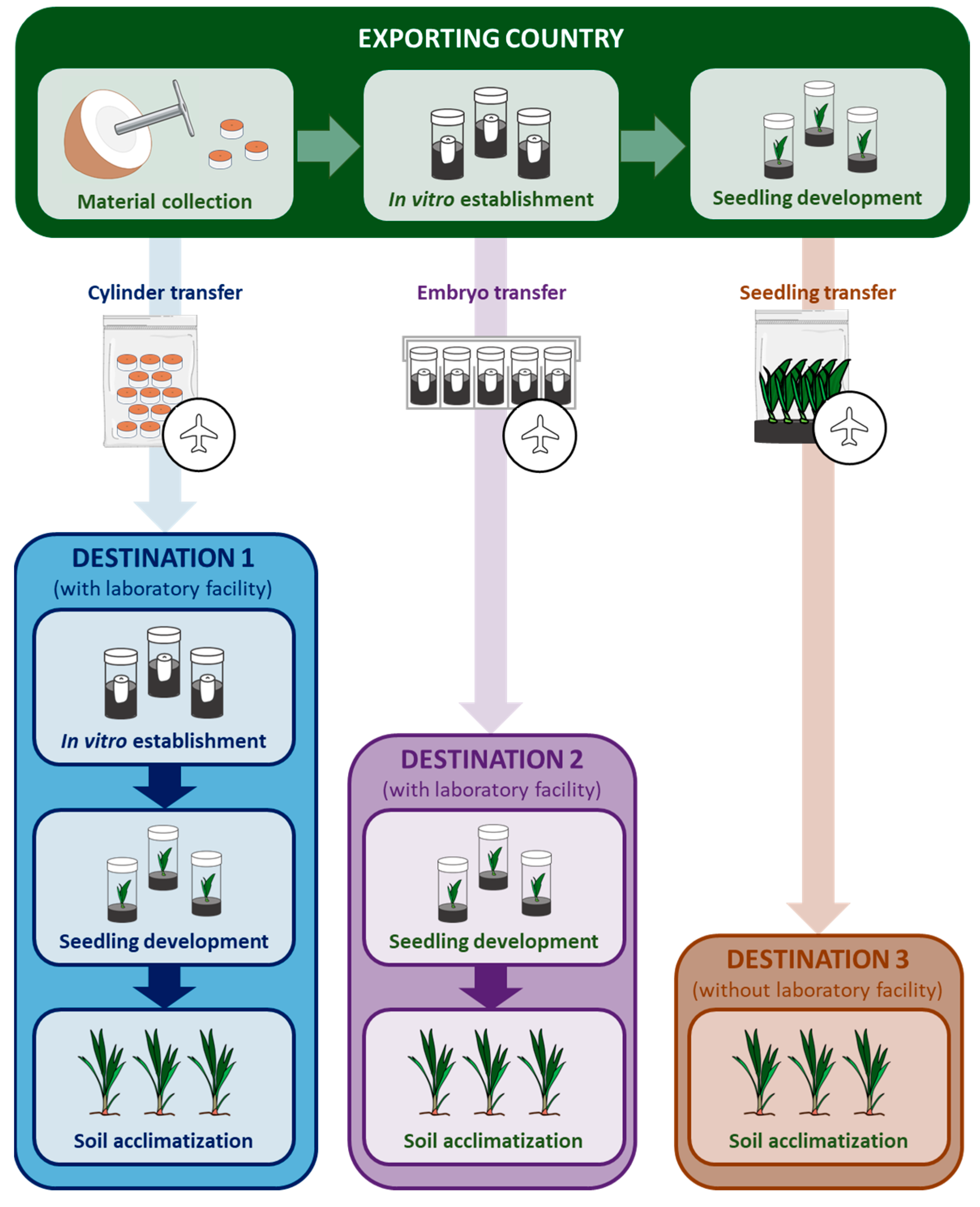

5.3. In Vitro Technology: A Key Tool for Coconut Germplasm Exchange

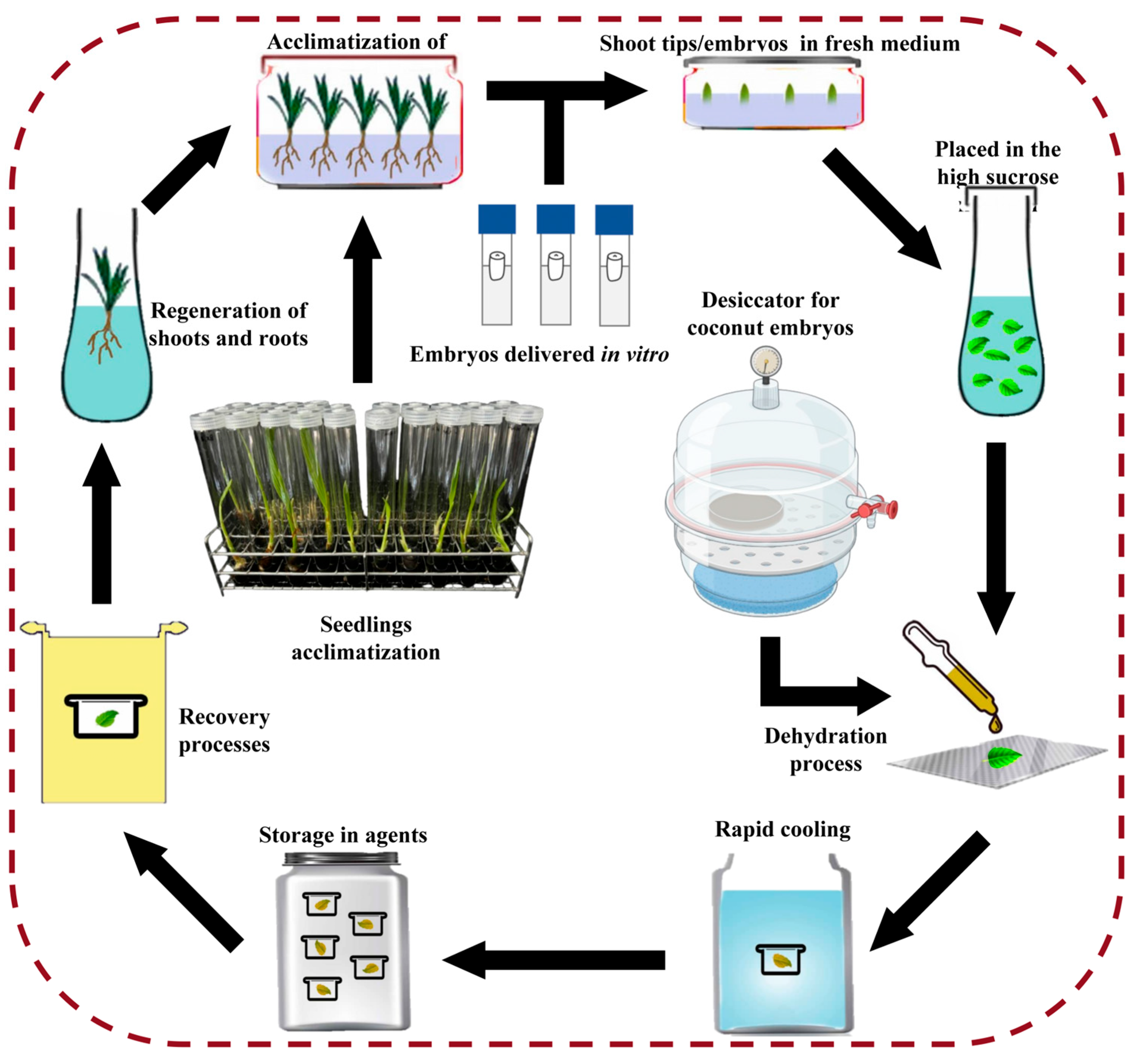

5.4. Cryopreservation: An Important Method for Preserving Long-Term Coconut Germplasm

5.5. Recovery or Acclimatization Processes After Germplasm Exchange

6. Restrains and Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GA | Gibberellin |

| GA20ox | GA-20 oxidase |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

| Fst | Fixation Index |

| QTL | Quantitative trait loci |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) |

| COGENT | Coconut Genetic Resources Network |

| ICC | International Coconut Community |

| LYDs | Lethal yellowing-type diseases |

| ICGs | International Coconut Gene Banks |

| WCT | West African Tall |

| MYD | Malayan Yellow Dwarf |

References

- Judd, W.; Campbell, C.; Kellogg, E.; Stevens, P.; Donoghue, M. Chapter 3—Plant Systematics: A Phylogenetic Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Kaleri, G.A.; Mu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Dou, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhou, J.; Luo, J.; et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis provides insights into the effect of epicuticular wax accumulation on salt stress in coconuts. Plants 2024, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Cao, G.; Shi, M.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, R.; et al. ArecaceaeMDB: A comprehensive multi-omics database for Arecaceae breeding and functional genomics studies. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Tran, B.-M.; Xu, H.; Yang, Z.; Qamar, U.Z.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, J. Exploring the potential application of coconut water in healthcare and biotechnology: A review. Beverage Plant Res. 2024, 4, e018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, N. C. Elevitch (ed): Speciality crops for the Pacific Islands: Permanent agriculture resources. Agrofor. Syst. 2011, 83, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niral, V.; Jerard, B.A.; Rajesh, M.K. Germplasm resources: Diversity and conservation. In The Coconut Genome; Rajesh, M.K., Ramesh, S.V., Perera, L., Kole, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, F. Use of biotechnologies for the conservation of plant biodiversity. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2011, 47, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.T.; Bandupriya, H.D.; Foale, M.; Adkins, S.W. Biology, propagation and utilization of elite coconut varieties (makapuno and aromatics). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 109, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.D.; Gautam, R.K.; Ahmad, I.; Roy, S.D.; Sharma, A. Biochemical, genetic and moleculra basis of the novel and commercially important soft endosperm Makapuna coconut—A review. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2015, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Phonphoem, W.; Sinthuvanich, C.; Aramrak, A.; Sirichiewsakul, S.; Arikit, S.; Yokthongwattana, C. Nutritional profiles, phytochemical analysis, antioxidant activity and DNA damage protection of makapuno derived from Thai aromatic coconut. Foods 2022, 11, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasekhar, S.; Chandran, K.P. World Economic Importance. In The Coconut Genome; Rajesh, M.K., Ramesh, S.V., Perera, L., Kole, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alouw, J.C.; Chinthaka, A.H.N.; Pirmansah, A.; Sintoro, O.; Ilmawan, B.; Hosang, K.D.; Soetopo, D.; Kardinan, A.; Samsudin; Marwanto, S. The economic, social and environmental importance of coconut. In Science-Based Pest Management for a Sustainable and Resilient Coconut Sector; Alouw, J.C., Chinthaka, A.H.N., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, B.F.; Baudouin, L.; Olsen, K.M. Independent origins of cultivated coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the old world tropics. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayar, N.M. The Coconut: Phylogeny, Origins, and Spread; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh, M.K.; Gangurde, S.S.; Pandey, M.K.; Niral, V.; Sudha, R.; Jerard, B.A.; Kadke, G.N.; Sabana, A.A.; Muralikrishna, K.S.; Samsudeen, K.; et al. Insights on genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium in globally diverse coconut accessions using genotyping-by-sequencing. Omics J. Integr. Biol. 2021, 25, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niral, V.; Jerard, B.A. Botany, Origin and Genetic Resources of Coconut. In The Coconut Palm (Cocos nucifera L.)—Research and Development Perspectives; Krishnakumar, V., Thampan, P.K., Nair, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 57–111. [Google Scholar]

- Baudouin, L. Genome studies for effective management and utilization of coconut genetic resources. In Coconut Biotechnology: Towards the Sustainability of the ‘Tree of Life’; Adkins, S., Foale, M., Bourdeix, R., Nguyen, Q., Biddle, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Foale, M.; Biddle, J.; Bazrafshan, A.; Adkins, S. Biology, ecology, and evolution of coconut. In Coconut Biotechnology: Towards the Sustainability of the ‘Tree of Life’; Adkins, S., Foale, M., Bourdeix, R., Nguyen, Q., Biddle, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Salum, U.; Foale, M.; Biddle, J.; Bazrafshan, A.; Adkins, S. Towards the sustainability of the “tree of life”: An introduction. In Coconut Biotechnology: Towards the Sustainability of the ‘Tree of Life’; Adkins, S., Foale, M., Bourdeix, R., Nguyen, Q., Biddle, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rethinam, P.; Krishnakumar, V. Tender coconut varieties. In Coconut Water: A Promising Natural Health Drink-Distribution, Processing and Nutritional Benefits; Rethinam, P., Krishnakumar, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam, V.; Rajesh, M.K. Coconut genetic diversity, conservation and utilization. In Biodiversity and Conservation of Woody Plants; Ahuja, M.R., Jain, S.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeix, R.; Konan Konan, J.L.; N’Cho, Y.P. Coconut. A Guide to Traditional and Improved Varieties; Diversiflora: Montpellier, France, 2005; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, L.; Baudouin, L.; Mackay, I. SSR markers indicate a common origin of self-pollinating dwarf coconut in South-East Asia under domestication. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 211, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantican, D.V.; Strickler, S.R.; Canama, A.O.; Gardoce, R.R.; Mueller, L.A.; Galvez, H.F. De novo genome sequence assembly of dwarf coconut (Cocos nucifera L. ‘Catigan Green Dwarf’) provides insights into genomic variation between coconut types and related palm species. G3 2019, 9, 2377–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudouin, L.; Lebrun, P. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) DNA studies support the hypothesis of an ancient Austronesian migration from Southeast Asia to America. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2009, 56, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pérez, J.M.; Cañas, G.P.; López, L.; Arias, T. Genome-wide diversity of northern South America cultivated Coconut (Cocus nucifera L.) uncovers diversification times and targets of domestication of coconut globally. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Iqbal, A.; Qadri, R. Breeding of Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.): The Tree of Life. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Fruits: Volume 3; Al-Khayri, J.M., Jain, S.M., Johnson, D.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 673–725. [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam, T.; Hatta, M.A.M. Improving Coconut Using Modern Breeding Technologies: Challenges and Opportunities. Plants 2022, 11, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, S.V.; Arunachalam, V.; Rajesh, M.K. Genomic Designing of Climate-Smart Coconut. In Genomic Designing of Climate-Smart Fruit Crops; Kole, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rethinam, P. International Scenario of Coconut Sector. In The Coconut Palm (Cocos nucifera L.)—Research and Development Perspectives; Krishnakumar, V., Thampan, P.K., Nair, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 21–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.T.; Bandupriya, H.D.; López-Villalobos, A.; Sisunandar, S.; Foale, M.; Adkins, S.W. Tissue culture and associated biotechnological interventions for the improvement of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.): A review. Planta 2015, 242, 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattapaglia, D.; Alves, W.; Pacheco, C.A.P. High-density linkage to physical mapping in a unique Tall × Dwarf coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) outbred F(2) uncovers a major QTL for flowering time colocalized with the FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1408239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Tang, L. Genetic diversity and differentiation of the Hainan Tall coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) as revealed by inter-simple sequence repeat markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Liu, R.; Zhang, J.; Mason, A.S.; Li, Z.; Gong, S.; Zhong, Y.; Dou, Y.; Sun, X.; Fan, H.; et al. Alternative splicing of flowering time gene FT is associated with halving of time to flowering in coconut. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Q.; Zou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, D. Induction and Transcriptome Analysis of Callus Tissue from Endosperm of Makapuno Coconut. Plants 2024, 13, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Sun, X.; Iqbal, A.; Yarra, R.; Wu, Q.; Li, J.; Lv, X.; Ye, J.; Yang, Y. Revealing the aromatic sonata through terpenoid profiling and gene expression analysis of aromatic and non-aromatic coconut varieties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Lai, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Ye, W.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, F.; Yang, J.; et al. Comparative Metabolomics Reveals Key Determinants in the Flavor and Nutritional Value of Coconut by HS-SPME/GC-MS and UHPLC-MS/MS. Metabolites 2022, 12, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas Neto, M.; Pereira, T.N.; Geronimo, I.G.; Azevedo, A.O.; Ramos, S.R.; Pereira, M.G. Coconut genome size determined by flow cytometry: Tall versus Dwarf types. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, gmr.15017470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, B.F.; Baudouin, L.; Beulé, T.; Ilbert, P.; Duperray, C.; Crisp, M.; Issali, A.; Konan, J.L.; Rival, A. Ploidy and domestication are associated with genome size variation in Palms. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Z.W.; Yuan, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Sun, P.; Sun, L.; Deng, Y.; et al. High-quality reference genome sequences of two coconut cultivars provide insights into evolution of monocot chromosomes and differentiation of fiber content and plant height. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okemo, P.; Wijesundra, U.; Nakandala, U.; Dillon, N.; Chandora, R.; Campbell, B.; Smith, M.; Hardner, C.; Cadorna, C.A.; Martin, G.; et al. Crop domestication in the Asia Pacific Region: A review. Agric. Commun. 2024, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bocs, S.; Fan, H.; Armero, A.; Baudouin, L.; Xu, P.; Xu, J.; This, D.; Hamelin, C.; Iqbal, A.; et al. Coconut genome assembly enables evolutionary analysis of palms and highlights signaling pathways involved in salt tolerance. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pérez, J.M.; Cañas, G.P.; López, L.; Arias, T. Genome-wide diversity analysis to infer population structure and linkage disequilibrium among Colombian coconut germplasm. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xu, P.; Fan, H.; Baudouin, L.; Xia, W.; Bocs, S.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Guo, A.; Zhou, L.; et al. The genome draft of coconut (Cocos nucifera). GigaScience 2017, 6, gix095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, R.E.S.; Cagayan, J.; Gardoce, R.R.; Manohar, A.N.C.; Canama-Salinas, A.O.; Rivera, R.L.; Lantican, D.V.; Galvez, H.F.; Reaño, C.E. Mining and validation of novel simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers derived from coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) genome assembly. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.S.; Goher, F.; Zhang, D.; Shi, P.; Li, Z.; Htwe, Y.M.; Wang, Y. Is CRISPR/Cas9 a way forward to fast-track genetic improvement in commercial palms? Prospects and limits. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1042828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Shi, P.; Htwe, Y.M.; Nie, H.; Ma, M.; Su, H.; Fang, X.; Ahmed, M.A.A.; et al. PEG-mediated transformation and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing of CnPDS in coconut protoplast. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 235, 121674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.; Ramaswamy, M.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Yang, C.; Kalaipandian, S. Breeding and Genetics for Coconut Improvement. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2024, 7, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M.A.; Huang, L.; Abdelaal, W.B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Sirohi, M.H.; Wang, F. Applications of Multi-Omics Technologies for Crop Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 563953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, K.; Abdullah, S.N.A.; Hatta, M.A.M.; Ling, K.L. Genomics and Transcriptomics Reveal Genetic Contribution to Population Diversity and Specific Traits in Coconut. Plants 2023, 12, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajanaidu, N.; Ainul, M.M. Conservation of Oil Palm and Coconut Genetic Resources. In Conservation of Tropical Plant Species; Normah, M.N., Chin, H.F., Reed, B.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.; Mridula, K. Technology mission on coconut—An overview. Indian Coconut J. 2016, 59, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lédo, A.; Oliveira, L.; Machado, C.; Silva, A.V.; Ramos, S. Strategies for exchange of coconut germplasm in Brazil. Ciência Rural 2017, 47, e20160391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.; Gupta, A.; Gopal, M.; Selvamani, V.; Mathew, J.; Surekha; Indhuja, S. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). In Soil Health Management for Plantation Crops: Recent Advances and New Paradigms; Thomas, G.V., Krishnakumar, V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 37–109. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, H.D.; Gowda, C.L.L.; Buhariwalla, H.K.; Crouch, J.H. Efficient use of crop germplasm resources: Identifying useful germplasm for crop improvement through core and mini-core collections and molecular marker approaches. Plant Genet. Resour. 2006, 4, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samosir, Y.M.S.; Adkins, S. Improving acclimatization through the photoautotrophic culture of coconut (Cocos nucifera) seedlings: An in vitro system for the efficient exchange of germplasm. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2014, 50, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdeix, R.; Coppens d’Eeckenbrugge, G.; Konan, J.L.; Novarianto, H.; Perera, C.; Wolf, V.L.F. Collecting Coconut Germplasm for Disease Resistance and Other Traits. In Coconut Biotechnology: Towards the Sustainability of the ‘Tree of Life’; Adkins, S., Foale, M., Bourdeix, R., Nguyen, Q., Biddle, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Borokini, T.I.; Okere, A.U.; Giwa, A.O.; Daramola, B.O.; Odofin, W.T. Biodiversity and conservation of plant genetic resources in the Field Genebank of the National Centre for Genetic Resources and Biotechnology, Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 2, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Karun, A.; Ramesh, S.V.; Rajesh, M.K.; Niral, V.; Sudha, R.; Muralikrishna, K.S. Conservation and Utilization of Genetic Diversity in Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). In Cash Crops: Genetic Diversity, Erosion, Conservation and Utilization; Priyadarshan, P.M., Jain, S.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 197–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wilms, H.; Bazrafshan, A.; Panis, B.; Adkins, S.W. Coconut Conservation and Propagation. In The Coconut: Botany, Production and Uses; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2024; pp. 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.M. Radiation-Induced Mutations for Date Palm Improvement. In Date Palm Biotechnology; Jain, S.M., Al-Khayri, J.M., Johnson, D.V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hayati, A.; Wickneswari, R.; Maizura, I.; Rajanaidu, N. Genetic diversity of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) germplasm collections from Africa: Implications for improvement and conservation of genetic resources. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanduri, K. Plant genetic resources: Advancing conservation and use through biotechnology. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2003, 3, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camadro, E.; Rimieri, P. Ex situ plant germplasm conservation revised at the light of mechanisms and methods of genetics. J. Basic Appl. Genet. 2021, 32, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halewood, M.; Chiurugwi, T.; Sackville Hamilton, R.; Kurtz, B.; Marden, E.; Welch, E.; Michiels, F.; Mozafari, J.; Sabran, M.; Patron, N.; et al. Plant genetic resources for food and agriculture: Opportunities and challenges emerging from the science and information technology revolution. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, F.; Engels, J. Technologies and strategies for ex situ conservation. In Proceedings of the Managing Plant Genetic Diversity, Proceedings of the an International Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12–16 June 2000; pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cueto, C.; Johnson, V.; Engelmann, F.; Kembu, A.; Louis, K.; Kouassi, M.; Rivera, R.L.; Vidhanaarachchi, V.; Bourdeix, R. Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement and Duplication of Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Germplasm Using Embryo Culture Transfer Protocols; COGENT: Montpellier, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekharan, P.E.; Srinivasan, G. Conservation and management of haploid genetic diversity through pollen cryopreservation. Palynology 2005, 41, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, W.W.; Towill, L.E. Chapter 5–Plant Breeding Reviews: Long-Term Pollen Storage. In Plant Breeding Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 179–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanec, B.; Murovec, J. Haploids and Doubled Haploids in Plant Breeding. In Plant Breeding; Abdurakhmonov, I.Y., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, G.M.; Johnson, A.C.; Ash, G.J.; Wilson, B.A.; Ero, M.M.; Pilotti, C.A.; Dewhurst, C.F.; You, M.S. Coconut Lethal Yellowing Diseases: A Phytoplasma Threat to Palms of Global Economic and Social Significance. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdeix, R.; Engels, J. A Global Strategy for the Conservation and Use of Coconut Genetic Resources 2018–2028; Bioversity International: Montpellier, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frison, E.; Putter, C.A.J.; Diekmann, M. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Coconut Germplasm; Bioversity International: Montpellier, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Oropeza, C.; Cordova, I.; Chumba, A.; Narváez, M.; Sáenz, L.; Ashburner, R.; Harrison, N. Phytoplasma distribution in coconut palms affected by lethal yellowing disease. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2011, 159, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batugal, P. International Coconut Genetic Resources Network (COGENT): Its history and achievements. CORD 2005, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, J.; Nguyen, Q.; Mu, Z.H.; Foale, M.; Adkins, S. Germplasm Reestablishment and Seedling Production: Embryo Culture. In Coconut Biotechnology: Towards the Sustainability of the ‘Tree of Life’; Adkins, S., Foale, M., Bourdeix, R., Nguyen, Q., Biddle, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ikin, R. Germplasm Health Management for COGENT’s Multi-site International Coconut Genebank. In Proceedings of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute—Regional Office for Asia, the Pacific and Oceania (IPGRI-APO), Serdang, Malaysia, 15–18 July 2023; pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Batugal, P.; Bourdeix, R.; Baudouin, L. Coconut Breeding. In Breeding Plantation Tree Crops: Tropical Species; Jain, S.M., Priyadarshan, P.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 327–375. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, S. Improving the Availability of Valuable Coconut Germplasm using Tissue Culture Techniques. CORD 2016, 32, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz, L.; Chan, J.L.; Narvaez, M.; Oropeza, C. Protocol for the Micropropagation of Coconut from Plumule Explants. In Plant Cell Culture Protocols; Loyola-Vargas, V.M., Ochoa-Alejo, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Nikila, A.; Renuka, R.; Kumar, K.; Mohanalakshmi, M.; Suresh, J.; Thavaprakash, N. Advances in coconut micropropagation: Prospects, constraints and way forward. Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12, 5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaipandian, S.; Mu, Z.; Kong, E.Y.Y.; Biddle, J.; Cave, R.; Bazrafshan, A.; Wijayabandara, K.; Beveridge, F.C.; Nguyen, Q.; Adkins, S.W. Cloning Coconut via Somatic Embryogenesis: A Review of the Current Status and Future Prospects. Plants 2021, 10, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Nguyen, V.A.; Nulu, N.P.C.; Kalaipandian, S.; Beveridge, F.C.; Biddle, J.; Young, A.; Adkins, S.W. Towards Pathogen-Free Coconut Germplasm Exchange. Plants 2024, 13, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mounika Sai, K.; Nair, S.; Mohan, M.; Kiran, A.G. Expression profiling of cell cycle regulatory genes E2F and CDKA during early stages of zygotic embryo culture in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 155, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, A.; Sudarma, S.; Kalaipandian, S.; Biddle, J.M.; Mu, Z.; Kong, E.Y.Y.; Nulu, N.P.C.; Adkins, S.W. New Method for Enhancing Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Embryo Dehydration: An Important Step Towards Proficient Cryopreservation. Plants 2025, 14, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisunandar; Novarianto, H.; Mashud, N.; Samosir, Y.M.S.; Adkins, S.W. Embryo maturity plays an important role for the successful cryopreservation of coconut (Cocos nucifera). In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2014, 50, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekharan, P.E.; Gowthami, R.; Magudeeswari, P. Cryopreserved Pollen: Applications in Biotechnology and Crop Improvement. In Pollen Cryopreservation Protocols; Rajasekharan, P.E., Gowthami, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.L.d.; Souza, E.H.d.; Vieira, L.d.J.; Pelacani, C.R.; Souza, F.V.D. Cryopreservation of pollen of wild pineapple accessions. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 219, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Fu, D.; Zhang, C.; Cai, C.; Ou, L. A simple pollen collection, dehydration, and long-term storage method for litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Sci. Hortic. 2015, 188, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinato, N.; Rita, I.; Santos, I.; Baccili, B.; Vigna, B.; Paula, A.; Fávero, A. Pollen Cryopreservation for Plant Breeding and Genetic Resources Conservation. Cryo Lett. 2020, 41, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, L.A. In-vitro conservation. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1991, 43, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, A. Ex situ conservation of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) germplasm using cryopreservation. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Höfer, M.; Hanke, M.-V. Cryopreservation of fruit germplasm. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2017, 53, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque-Borda, C.A.; Kulus, D.; Vacaro de Souza, A.; Kaviani, B.; Vicente, E.F. Cryopreservation of Agronomic Plant Germplasm Using Vitrification-Based Methods: An Overview of Selected Case Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisunandar; Rival, A.; Turquay, P.; Samosir, Y.; Adkins, S.W. Cryopreservation of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) zygotic embryos does not induce morphological, cytological or molecular changes in recovered seedlings. Planta 2010, 232, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandupriya, H.D.D.; Perera, S.A.C.N.; Ranasinghe, C.S.; Yalegama, C.; Hewapathirana, H.P.D.T. Physiological, biochemical and molecular evaluation of micropropagated and seed-grown coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) palms. Trees 2022, 36, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisunandar, S.; Rival, A.; Samosir, Y.; Adkins, S. Cryopreservation of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.): The influence of embryo maturity upon rate of recovery and fidelity of seedlings. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Anim. 2010, 232, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermode, A.; Finch-Savage, B. Desiccation Sensitivity in Orthodox and Recalcitrant Seeds in Relation to Development; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 149–184. [Google Scholar]

- Vineesh, P.S.; Skaria, R.; Mukunthakumar, S.; Padmesh, P.; Decruse, S.W. Seed germination and cryostorage of Musa acuminata subsp. burmannica from Western Ghats. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 100, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N. Long-term storage of oil palm germplasm zygotic embryo using cryopreservation. J. Oil Palm Res. 2017, 29, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, J.E.; Sutter, E.G. Acclimatization of micropropagated plants to the greenhouse and field. In Micropropagation: Technology and Application; Debergh, P.C., Zimmerman, R.H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lédo, A.; Jenderek, M.; Skogerboe, D.; Staats, E.; Machado, C.; Oliveira, L. Cryopreservation of zygotic embryos of the Brazilian Green Dwarf coconut. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2018, 53, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lédo, A.; Passos, E.; Fontes, H.; Ferreira, J.; Talamini, V.; Vendrame, W. Advances in Coconut palm propagation. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2019, 41, e-159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, H.; Rhee, J.; Rivera, R.L.; Longin, K.; Panis, B.J.A.H. Developing coconut cryopreservation protocols and establishing cryo-genebank at RDA; a collaborative project between RDA and Bioversity International. In Proceedings of the III International Symposium on Plant Cryopreservation, Bangkok, Thailiand, 26 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Welewanni, I.; Jayasekera, A.; Bandupriya, H. Coconut Cryopreservation: Present Status and Future Prospects. CORD 2017, 33, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alansi, S.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Nadeem, M.; Khan, S.; Tarroum, M.; Alshameri, A.; Gaafar, A.-R.Z. Cryopreservation: A tool to conserve date palm in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1896–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Din, M.; Solliman, M.E.-D.; Alkhateeb, A.; Heba, A.; Mohasseb, H.; Aldaej, M.; Al-Khateeb, S. Towards development of new technique for cryopreservation of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in vitro grown cultures. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2019, 28, 6256–6263. [Google Scholar]

- Palanyandy, S.R.; Gantait, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Sinniah, U.R. Cryopreservation of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) polyembryoids via encapsulation-desiccation. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ree, J.F.; Guerra, M.P. Exogenous inorganic ions, partial dehydration, and high rewarming temperatures improve peach palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) embryogenic cluster post-vitrification regrowth. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2021, 144, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, Y.P.S. Cryopreservation of Pollen and Pollen Embryos, and the Establishment of Pollen Banks. In International Review of Cytology; Bourne, G.H., Jeon, K.W., Friedlander, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 107, pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalita, P.M.; Damasco, O.P.; Samosir, Y.M.S.; Mashud, N.; Novariento, H.; Rillo, E.P.; Lien, V.T.; Kembu, A.; Fauare, M.; Adkins, S.W. An enhanced embryo culture methodology for coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2015, 4, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assy-Bah, B.; Engelmann, F. Cryopreservation of immature embryos of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Cryo Lett. 1992, 13, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- N’Nan, O.; Borges, M.; Konan, J.L.K.; Hocher, V.; Verdeil, J.L.; Tregear, J.; N’guetta, A.S.P.; Engelmann, F.; Malaurie, B. A simple protocol for cryopreservation of zygotic embryos of ten accessions of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2012, 48, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopade, P.A.; Samosir, Y.M.; Rival, A.; Adkins, S.W. Dehydration improves cryopreservation of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Cryobiology 2010, 61, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto, C.; Rivera, R.; Kim, H.-H.; Kong, H.; Baek, H.-J.; Sebastian, L.; Park, H. Development of Cryopreservation Protocols for Cryobanks of Coconut Zygotic Embryos. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1039, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajini, K.K.; Karun, A.; Amamath, C.H.; Engelmann, F. Cryopreservation of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) zygotic embryos by vitrification. Cryo Lett. 2011, 32, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karun, A.; Sajini, K. Cryopreservation of Coconut Zygotic Embryos and Pollen; Central Plantation Crops Research Institute: Kasaragod, Phillipine, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe, J.; Weerakoon, L.; Weerakoon, S. Studies on cryopreservation of mature zygotic embryos of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Proc. Sri Lanka Assoc. Adv. Sci. 2002, 58, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Speaker Abstracts. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Anim. 2010, 46, 1–92. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Shi, P.; Khan, F.S.; Htwe, Y.M.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Wei, X.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, K.; Wang, Y. Cryopreservation and Cryotolerance Mechanism in Zygotic Embryo and Embryogenic Callus of Oil Palm. Forests 2023, 14, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, F.; Chabrillange, N.; Dussert, S.; Duval, Y. Cryopreservation of zygotic embryos and kernels of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Seed Sci. Res. 1995, 5, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veira, P.; Wei, S.Q.; Ukah, U.V.; Healy-Profitós, J.; Auger, N. Black-White Inequality in Outcomes of In Vitro Fertilization: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.H. In vitro plant cloning systems. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1981, 21, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelak, M.; Pacholczak, A.; Nowakowska, K. Challenges and insights in the acclimatization step of micropropagated woody plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 159, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afreen, F. Physiological and Anatomical Characteristics of In Vitro Photoautotrophic Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Narváez, M.; Gómez-Falcón, N.; Oropeza, C. Protocol for the Acclimatization of Coconut Vitro-Plants Under Ex Vitro Conditions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2827, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, G.; Talavera, C.; Oropeza, C.; Desjardins, Y.; Santamaria, J.M. Exogenous sucrose can decrease in vitro photosynthesis but improve field survival and growth of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in vitro plantlets. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2005, 41, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropeza, C.; Sandoval-Cancino, G.; Sáenz, L.; Narváez, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Chan, J.L. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Somatic Embryogenesis Using Immature Inflorescence Explants. In Step Wise Protocols for Somatic Embryogenesis of Important Woody Plants: Volume II; Jain, S.M., Gupta, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Z.; Li, Z.; Nulu, N.P.C.; Kalaipandian, S.; Biddle, J.M.; Bazrafshan, A.; Kong, E.; Adkins, S.W. A Photomixotrophic System to Improve the Growth of In Vitro-Cultured Seedlings of Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisunandar; Alkhikmah; Husin, A.; Julianto, T.; Yuniaty, A.; Rival, A.; Adkins, S.W. Ex vitro rooting using a mini growth chamber increases root induction and accelerates acclimatization of Kopyor coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) embryo culture-derived seedlings. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2018, 54, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalita, P.; Damasco, O.; Adkins, S. Effect of medium replenishment and acclimatization techniques on growth and survival of embryo cultured coconut seedlings. Philipp. Sci. Lett. 2010, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bett, C.; Mweu, C.; Nyende, A.B. African Journal of Biotechnology In vitro regeneration of coconut (Cocos nucifera L) through indirect somatic embryogenesis in Kenya. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalita, P.; Damasco, O.; Adkins, S. Effect of Chemical and Physical Treatments on the In Vitro Germination and Growth of ‘Laguna Tall’ Coconut Embryos. Crop Prot. Newsl. 2010, 35, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Falcón, N.; Sáenz-Carbonell, L.A.; Andrade-Torres, A.; Lara-Pérez, L.A.; Narváez, M.; Oropeza, C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi increase the survival and growth of micropropagated coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) plantlets. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2023, 59, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, C.; Rahman, M.A.; Argaman, E.; Xiao, Y. Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the field promotes plant colonization rate and yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 164, 127503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.W.; Hoeksema, J.D.; Gehring, C.A.; Johnson, N.C.; Klironomos, J.N.; Abbott, L.K.; Pringle, A. The promise and the potential consequences of the global transport of mycorrhizal fungal inoculum. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, E.; Bedini, S. Enhancing ecosystem services in sustainable agriculture: Biofertilization and biofortification of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, F.; Juraimi, A.S.; Ahmad-Hamdani, M.S.; Alam, M.A.; Hasan, M.M.; Hashemi, F.S.G.; Bahram, M. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant invasion trajectory. Plant Soil 2019, 441, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluru, A.; Prakash, K.; Neema, M.; Muralikrishna, K.S.; Samsudeen, K.; Chandran, K.P.; Rajesh, M.K.; Karun, A. Pollen storage of coconut dwarf accession Chowghat Orange Dwarf at low temperature. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 91, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karun, A.; Sjini, K.K.; Niral, V.; Amarnth, C.H.; Remya, P.; Rajesh, M.K.; Samsudeen, K.; Jerard, B.A.; Engelmann, F. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) pollen cryopreservation. Cryo Lett. 2014, 35, 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Jiji, K.; Palayyan, M. Identification and characterization of phytoconstituents of ethanolic root extract of Clitoria ternatea L. utilizing HR-LCMS analysis. Plant Sci. Today 2021, 8, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Tran, B.-M.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Pham, T.T.-T.; Le, M.-A.; Indrachapa, M.T.N.; Nguyen, P.T.; Luo, J. Optimized In Vitro Method for Conservation and Exchange of Zygotic Embryos of Makapuno Coconut (Cocos nucifera). Horticulturae 2025, 11, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-A.; Nguyen, P.T.; Le, M.-A.; Bazrafshan, A.; Sisunandar, S.; Kalaipandian, S.; Adkins, S.W.; Nguyen, Q.T. A practical framework for the cryopreservation of palm species. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2023, 59, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, H.; De Bièvre, D.; Longin, K.; Swennen, R.; Rhee, J.; Panis, B. Development of the first axillary in vitro shoot multiplication protocol for coconut palms. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lah, N.H.C.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Mediani, A.; Azizan, K.A.; Aizat, W.M.; Tan, J.K.; Afzan, A.; Noor, N.M.; Rohani, E.R. An Insight into the Behaviour of Recalcitrant Seeds by Understanding Their Molecular Changes upon Desiccation and Low Temperature. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, E.Y.Y.; Biddle, J.; Kalaipandian, S.; Bazrafshan, A.; Mu, Z.; Adkins, S.W. Improvement of somatic embryo maturation and shoot formation in somatic embryogenesis of Asian coconut varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 343, 114069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.S.; Li, Z.; Shi, P.; Zhang, D.; Htwe, Y.M.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y. Transcriptional Regulations and Hormonal Signaling during Somatic Embryogenesis in the Coconut Tree: An Insight. Forests 2023, 14, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirubha, C.; Renuka, R.; Kokiladevi, E.; Rajasree, V.; Sudhalakshmi, C.; Rajesh, S. Molecular insights of somatic embryogenesis in coconut. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konan, E.K.; Durand-Gasselin, T.; Kouadio, Y.J.; Niamké, A.C.; Dumet, D.; Duval, Y.; Rival, A.; Engelmann, F. Field development of oil palms (Elaeis guineensis jacq) originating from cryopreserved stabilized polyembryonic cultures. Cryo Lett. 2007, 28, 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Welewanni, I.; Perera, C.; Jayasekera, A.; Bandupriya, H. Recovery, histological observations and genetic integrity in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) embryogenic calli cryopreserved using encapsulation-dehydration procedure. J. Natl. Sci. Found. Sri Lanka 2020, 48, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospísilová, J.; Synková, H.; Haisel, D.; Semorádová, S. Acclimation of plantlets to Ex vitro conditions: Effects of air humidity, irradiance, CO2 concentration and abscisic acid (a Review). Acta Hortic. 2007, 748, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.; Hughes, H. In vitro acclimatization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) plantlets: A quantitative comparison of epicuticular leaf wax as a function of polyethylene glycol treatment. Plant Cell Rep. 1995, 15, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, A.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Gil-Pelegrín, E.; Leide, J.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Burghardt, M.; Riederer, M. Cuticular wax coverage and its transpiration barrier properties in Quercus coccifera L. leaves: Does the environment matter? Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samo, N.; Trejo-Arellano, M.G.; Gahurová, L.; Erban, A.; Ebert, A.; Rivière, Q.; Kubásek, J.; Aflaki, F.; Mondeková, H.H.; Schlereth, A.; et al. Polycomb repressive complex 2 facilitates the transition from heterotrophy to photoautotrophy during seedling emergence. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.R.; Soares, M.N.B.; Silva, M.C.R.; Lima, M.C.; Silva-Moraes, V.K.d.O.; Alves, G.L.; Ríos-Ríos, A.M.; Lima, A.d.S.; Pinheiro, M.V.M.; Corrêa, T.R.; et al. Unlocking the Potential of In Vitro Photoautotrophy for Eryngium foetidum: Biomass, Morphophysiology, and Acclimatization. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Techniques | Treatments | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Coconut embryo culture laboratories are available in both exporting and destination countries | ||

| Embryos |

| [67,73] |

| The coconut embryo culture laboratory is only available in exporting country | ||

| Embryo-cultured seedlings |

| [67] |

| The coconut embryo culture laboratory is only available in the destination country | ||

| Endosperm cylinders |

| [76] |

| No coconut embryo culture laboratory is available in either the exporting or destination country | ||

| Seed nuts |

| [72,73,77] |

| Pollen |

| [73,78] |

| Explant Type | Sucrose Preculture | Cryopreservation Protocol | Survival/Regrowth Rate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) | ||||

| Zygotic embryos | N/A | Silica gel dehydration—LN freezing: silica gel dehydration (8 h) + LN storage (24 h) | 65% regrowth, 20–40% establishment | [100] |

| 0.3 M sucrose (3 d) + 0.6 M sucrose (3 d) | Vitrification (PVS3)—LN storage: PVS3 solution treatment (16 h) + LN storage (24 h) | 70–80% survival, 20–25% regrowth, 22% establishment | [101] | |

| 0.6 M sucrose + 0.01 M gelrite (72 h) | Vitrification (PVS3)—LN storage: PVS3 treatment (16 h) + LN storage (72 h) | 73% survival | [102] | |

| Plumule | 0.6 M sucrose + 0.01 M gelrite (72 h) | Droplet vitrification (PVS2/PVS3)—LN storage: PVS2/PVS3 exposure at 0 °C (15 min) + LN storage (24 h) | 96% survival | [103] |

| Meristem | N/A | Droplet vitrification (PVS2)—LN storage: PVS2 exposure at 0 °C (20/35/50 min) + LN storage (duration unspecified) | 82.3% survival | [104] |

| Embryogenic calli | 0.75 M sucrose (72 h) | Encapsulation–dehydration—LN storage: silica gel dehydration (20 h) + LN storage (2 h) | 45% survival, 25% regrowth | [105] |

| Species | Explant | Core Method | Survival/ Regrowth Rate | Take-Home Lessons for Coconut | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) | Embryogenic callus | Encapsulation–dehydration (2–4 h laminar air flow) + vitrification (PVS2 at 25 °C, 0/15/30/60/120 min) + LN storage (≥48 h) | 86.7% survival, 53.5% regrowth | Two-step encapsulation widens PVS2 window; coconut embryos can be bead-immobilized to ease handling and cut mechanical injury. | [106] |

| Laminar airflow dehydration (20 min, target moisture content 65%) → LN storage | 80% survival, 70% regrowth | Short (20 min) airflow drying gives clear moisture benchmark; coconut can adopt the same rapid, chemical-free desiccation step. | [107] | ||

| Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) | Poly- embryoids | PVS2 exposure at 0 °C (10 min) → LN storage (1 h) | 68% survival | Ultra-short droplet-PVS2 treatment is sufficient; coconut can switch from long bath to 10 min micro-droplet, saving time and reagent. | [108] |

| Laminar air flow dehydration (9 h) → LN storage (1 h) | 73.3% survival | Ambient-air dehydration works for Arecaceae; coconut can use overnight airflow cabinets when silica gel is not functional. | [108] | ||

| Peach palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) | Somatic embryo | Partial air dehydration (1–3 h) → PVS3 exposure (60–240 min) → direct LN submersion (1 min) | 60–90% survival | Wide PVS3 tolerance (60–240 min) reduces over-exposure risk; coconut can replace PVS2 with PVS3 and extend incubation safely. | [109] |

| In Vitro Development and Pre-Acclimatization | Ex Vitro Acclimatization and Nursery | Notable Results | Reference |

| Liquid culture Explant: zygotic embryos (Malayan Green Dwarf) Medium: Y3 + 45 g·L−1 sucrose + 2.5 g·L−1 activated charcoal Vessel: 500 mL bottle, 50 mL medium Subculture: Every 2 months Illumination: 16 h, 50 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 27 ± 2 °C | Misting irrigation Container: Plastic bag Substrate: Peatmoss, sand, soil (1:1:1) Illumination: 13 h, 120 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 28 ± 10 °C Humidity: 80–95% |

| [95] |

| Liquid culture Explant: zygotic embryos (Laguna Tall) Medium: Y3 + 60 g·L−1 sucrose + 0–20 mg·L−1 PVP or PEG + 1 g·L−1 activated charcoal Vessel: 400 mL bottle, 100 mL medium Nutrient replenishment: Every 60 days for 2 times Illumination: 16 h, 120 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 25 ± 1 °C | Misting irrigation, plastic tent, wooden box humidity chamber Selection: 3-leaf seedlings Fungicide: 2 g·L−1 BenlateTM, 15 min Container: 12 cm pots Substrate: Garden soil + coir (1:1) |

| [111] |

| Photoautotrophic system Medium: Y3 + 0–60 g·L−1 sucrose Vessel: 500 mL bottle, 40 mL medium CO2: 1600 μmol·mol−1 (day), 350 μmol·mol−1 (night) Illumination: 16 h, 90 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 29 ± 1 °C Humidity: 85 ± 5% | Opened photoautotrophic system Chamber: 110 × 50 × 40 cm acrylic Container: 17 × 14 cm pots Substrate: Soil, sand, compost (1:1:1) Temperature: 25 ± 5 °C Humidity: 60% | Increased survival (40→100%), reduced acclimatization time (10→6 months) | [130] |

| Liquid culture Explant: xygotic embryos (Kopyor Brown Dwarf) Medium: HEC + 30 g·L−1 sucrose + 2 g·L−1 activated charcoal Illumination: 14 h photoperiod (25 ± 2 μmol·m−2·s−1) Temperature: 27 ± 2 °C | Mini-growth chamber Selection: 2-leaf seedlings Fungicide: 2% Dithane, 20 min Chamber: 70 × 40 × 40 cm glass Medium: Sucrose-free HEC + 1 µM IBA Container: 7 × 10 cm pots Substrate: Cocopeat + rice charcoal (1:1) Illumination: 14 h, 40 ± 2 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 27 ± 2 °C Humidity: 85 ± 5% | 90% acclimatization success, low contamination, reduced labor | [130] |

| Liquid culture Explant: Plumule and inflorescence Medium: Y3 + 50 g·L−1 sucrose + 2.5 g·L−1 activated charcoal Vessel: 300 mL bottle, 100 mL medium Subculture: Every 2 months Illumination: 16 h, 60 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 27 ± 2 °C | Transparent plastic cover Selection: 4-leaf seedlings Container: Plastic potting bag Substrate: Peat, sand, soil (1:1:1) | Protocol not detailed | [131] |

| Liquid culture Explant: zygotic embryos (East African Tall) Medium: Y3 + 5 µM IBA+ 0.5 µM GA3 + 40 g·L−1 sucrose + 1 g·L−1 activated charcoal Vessel: 300 mL bottle, 100 mL medium Illumination: 16 h photoperiod | Misting irrigation Selection: 3-leaf seedlings Substrate: Soil, sand, manure (3:1:1) Foliar fertilizer: Every 21 days Temperature: 28 ± 2 °C Humidity: 75 ± 5% | New protocol achieved 40–60% survival | [132] |

| Pre-acclimatization chamber Explant: Cryo- and non-cryopreserved zygotic embryos (Malayan Yellow Dwarf, Xiem Green Dwarf) Selection: 5-month-old Seedlings Medium: Y3 + 100 µM NAA + 15 g·L−1 sucrose CO2: 1600 μmol·mol−1 Illumination: 600 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 27 ± 2 °C | Mini-growth chamber Selection: 8-month-old seedlings Chamber: 160 × 80 × 80 cm glass Container: 12 × 12 cm pots Medium: Sucrose-free Y3 Substrate: Cocopeat + rice charcoal (1:1) Foliar fertilizer: Seasol® seaweed solution Illumination: 14 h, 45 μmol·m−2·s−1 Temperature: 27 ± 2 °C Humidity: 90 ± 5% | 89% survival for embryo-cultured; 85% for cryopreserved embryos | [129] |

| In vitro and pre acclimatization Explant: Plumule (Mexican Tall) Protocols: not specified | Transparent plastic cover Selection: 3–4 leaf seedlings Container: 21 × 35 cm plastic bag Substrate: Peat, sand, soil (1:1:1) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: 10–15 g per 2.5 kg substrate | Native AMF increased survival by 1.19–1.24× | [82] |

| Technique | Key Features | Major Advantages | Major Limitations/Risks | Suitability for Breeding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollen Transfer |

|

|

| Medium: Useful for introducing specific alleles via controlled crossing, but not for conserving specific genotypes. | [139,140,141] |

| Embryo Culture/Exchange |

|

|

| High: Ideal for conserving specific populations and elite hybrids. Provides full genetic complement for selection. | [83,142] |

| In vitro Collection and Short-term Storage |

|

|

| High: Excellent for medium-term storage, rapid multiplication, and international exchange of disease-free clones. | [143,144] |

| Cryopreservation |

|

|

| Very High: The gold standard for long-term conservation of base collections, securing genetic diversity for future breeding. | [85,145] |

| Somatic Embryogenesis |

|

|

| Very High (with caution): Unparalleled for scaling up superior genotypes. Requires careful monitoring of genetic fidelity. | [146,147,148] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, K.; Yang, S.; Sisunandar, S.; Tran, B.-M.; Kottekate, M.; Shaftang, N.; Mu, Z. Biotechnologies for Promoting Germplasm Resource Utilization and Preservation of the Coconut and Important Palms. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121461

Deng K, Yang S, Sisunandar S, Tran B-M, Kottekate M, Shaftang N, Mu Z. Biotechnologies for Promoting Germplasm Resource Utilization and Preservation of the Coconut and Important Palms. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121461

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Ke, Shuya Yang, Sisunandar Sisunandar, Binh-Minh Tran, Mridula Kottekate, Nancy Shaftang, and Zhihua Mu. 2025. "Biotechnologies for Promoting Germplasm Resource Utilization and Preservation of the Coconut and Important Palms" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121461

APA StyleDeng, K., Yang, S., Sisunandar, S., Tran, B.-M., Kottekate, M., Shaftang, N., & Mu, Z. (2025). Biotechnologies for Promoting Germplasm Resource Utilization and Preservation of the Coconut and Important Palms. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121461