Enhancing Establishment of Young Chestnut Trees Under Water-Limited Conditions: Effects of Ridge Planting and Foil Mulching on Growth, Physiology, and Stress Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Basic Measurements

2.3. Determination of the Photosynthetic Pigments in the Leaves

2.4. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds

2.5. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

2.6. Chemicals

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Vegetative Growth and Physiological Performance in the First Year After Planting

3.2. Vegetative and Physiological Development in the Second Year After Planting

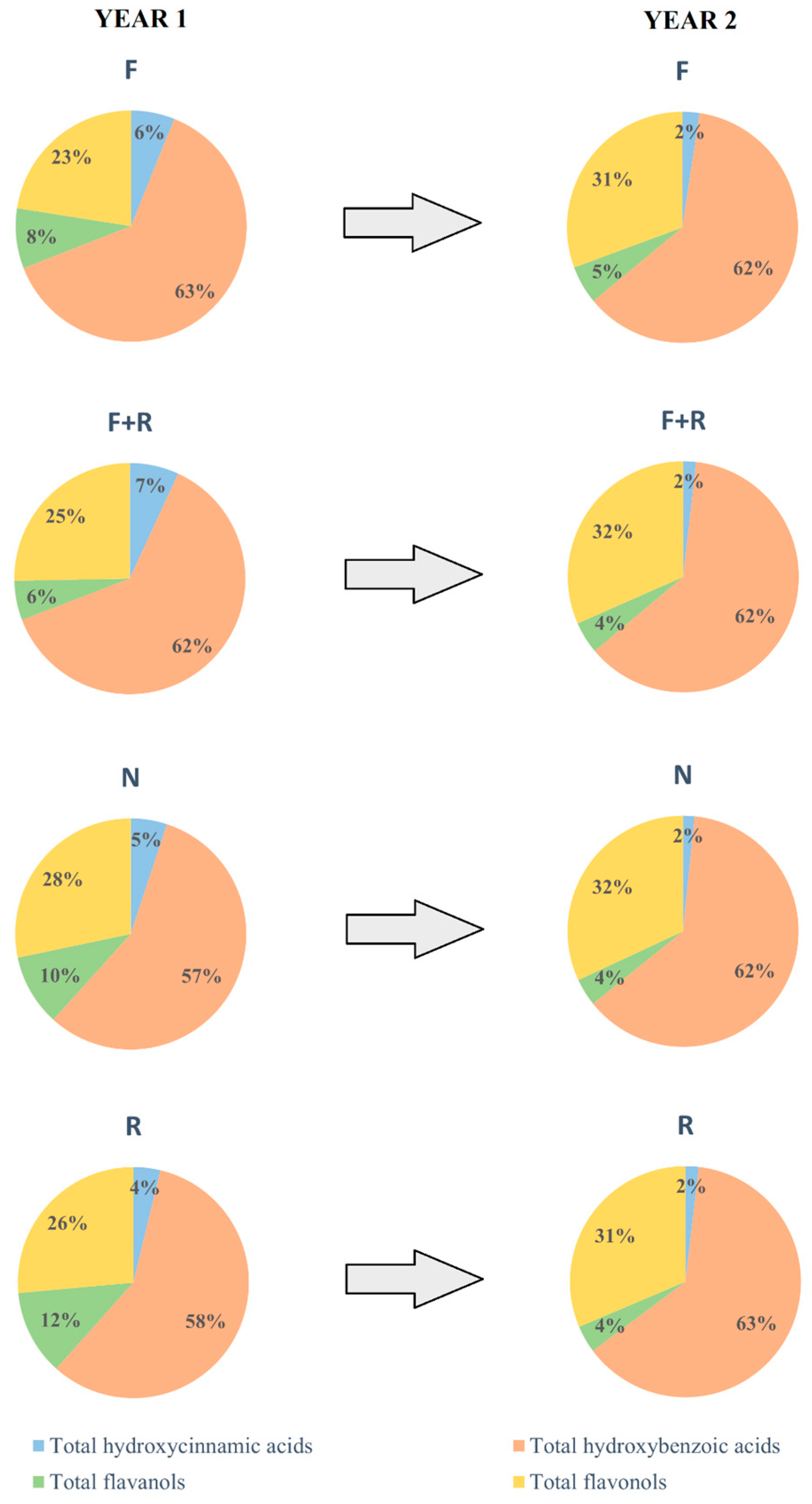

3.3. Changes in Phenolic Composition Between First and Second Year After Planting

| Phenolic Content in Leaves (mg/kg DW) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foil | No Foil | |||

| Compound | No Ridge | Ridge | No Ridge | Ridge |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | ||||

| 5-O-p-coumaroylquinic acid | 2.57 ± 0.06 a | 2.73 ± 0.31 a | 2.93 ± 0.01 a | 2.88 ± 0.23 a |

| Cryptochlorogenic acid (4-caffeoylquinic acid) | 0.22 ± 0.05 ab | 0.10 ± 0.02 a | 0.22 ± 0.02 ab | 0.30 ± 0.01 b |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | ||||

| Gallic acid | 0.80 ± 0.04 a | 0.53 ± 0.21 a | 0.73 ± 0.09 a | 2.00 ± 0.09 b |

| Gallic acid derivative 1 | 0.44 ± 0.07 b | 0.29 ± 0.05 b | 3.58 ± 0.01 a | 3.44 ±0.14 a |

| Gallic acid derivative 2 | 1.35 ± 0.08 a | 1.24 ± 0.06 a | 1.67 ± 0.07 a | 3.82 ± 0.18 b |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 1 | 1.01 ± 0.08 a | 0.75 ± 0.18 a | 0.63 ± 0.03 a | 4.05 ± 0.21 b |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 2 | 0.94 ± 0.09 a | 0.66 ± 0.09 a | 0.66 ± 0.03 a | 3.17 ± 0.21 b |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid derivative 1 | 1.64 ± 0.15 a | 1.36 ± 0.10 a | 0.91 ± 0.04 a | 5.48 ± 0.32 b |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid derivative 2 | 1.82 ± 0.10 a | 1.57 ± 0.05 a | 1.55 ± 0.05 a | 4.19 ± 0.33 b |

| Chestanin | 17.95 ± 0.20 bc | 16.36 ± 0.30 b | 21.23 ± 0.14 a | 18.91 ± 0.79 c |

| Isochestanin | 2.95 ± 0.13 b | 2.85 ± 0.03 b | 3.97 ± 0.03 a | 3.74 ± 0.21 a |

| Flavanols | ||||

| (+) Catechin | 1.35 ± 0.21 b | 0.70 ± 0.22 b | 3.50 ± 0.23 a | 4.99 ± 0.27 c |

| Procyanidin pentoside | 2.52 ± 0.41 a | 1.58 ± 0.03 a | 2.69 ± 0.17 a | 5.02 ± 0.47 b |

| Flavonols | ||||

| Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 4.48 ± 0.42 b | 4.66 ± 0.07 b | 6.14 ± 0.09 a | 8.16 ± 0.45 c |

| Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 0.61 ± 0.11 b | 0.50 ± 0.03 b | 1.41 ± 0.03 a | 1.84 ± 0.13 c |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 1.92 ± 0.13 b | 2.32 ± 0.03 b | 4.15 ± 0.04 a | 4.77 ± 0.24 c |

| Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 0.21 ± 0.07 c | 0.23 ± 0.03 ac | 0.43 ± 0.01 ab | 0.57 ± 0.06 b |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | 0.21 ± 0.08 b | 0.24 ± 0.03 b | 0.33 ± 0.02 ab | 0.52 ± 0.07 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide | 0.96 ± 0.07 b | 0.79 ± 0.03 b | 1.78 ± 0.03 a | 2.34 ± 0.17 c |

| Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 0.68 ± 0.05 b | 0.71 ± 0.01 b | 1.38 ± 0.02 a | 1.55 ± 0.07 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 0.62 ± 0.14 b | 0.55 ± 0.04 b | 1.19 ± 0.03 a | 1.54 ± 0.14 a |

| Kaempferol-3-O-(6ˇ-O-acetyl)glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside | 0.64 ± 0.10 ab | 0.39 ± 0.01 a | 0.66 ± 0.04 ab | 0.91 ± 0.11 b |

| Total hydroxycinnamic acids | 2.80 ± 0.10 a | 2.83 ± 0.32 a | 3.15 ± 0.02 a | 3.18 ± 0.24 a |

| Total hydroxybenzoic acids | 28.88 ± 0.68 b | 25.61 ± 0.96 b | 34.94 ± 0.14 a | 48.54 ± 2.27 c |

| Total flavanols | 3.87 ± 0.61 b | 2.28 ± 0.25 b | 6.19 ± 0.39 a | 10.02 ± 0.70 c |

| Total flavonols | 10.33 ± 1.16 b | 10.40 ± 0.24 b | 17.47 ± 0.30 a | 22.19 ± 1.31 c |

| TAPC | 45.87 ± 2.50 b | 41.12 ± 1.33 b | 61.76 ± 0.74 a | 83.93 ± 4.22 c |

| Phenolic Content in Leaves (mg/kg DW) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foil | No Foil | |||

| Compound | No Ridge | Ridge | No Ridge | Ridge |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | ||||

| 5-O-p-coumaroylquinic acid | 1.20 ± 0.07 b | 0.71 ± 0.10 a | 0.81 ± 0.07 a | 1.02 ± 0.08 ab |

| Cryptochlorogenic acid (4-caffeoylquinic acid) | 0.58 ± 0.06 a | 0.37 ± 0.07 a | 0.40 ± 0.08 a | 0.38 ± 0.07 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | ||||

| Gallic acid | 2.94 ± 0.06 a | 3.04 ± 0.10 a | 3.18 ± 0.45 a | 2.96 ± 0.10 a |

| Gallic acid derivative 1 | 0.51 ± 0.08 a | 0.50 ± 0.16 a | 0.38 ± 0.13 a | 0.31 ± 0.11 a |

| Gallic acid derivative 2 | 3.01 ± 0.19 a | 2.81 ± 0.30 a | 3.62 ± 0.21 a | 3.16 ± 0.18 a |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 1 | 10.60 ± 0.13 a | 8.53 ± 0.22 b | 11.07 ± 0.63 a | 10.76 ± 0.28 a |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 2 | 3.40 ± 0.12 a | 2.72 ± 0.21 a | 3.12 ± 0.24 a | 3.34 ± 0.16 a |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid derivative 1 | 10.11 ± 0.21 a | 8.27 ± 0.29 b | 10.11 ± 0.33 a | 10.66 ± 0.36 a |

| Hexahydroxydiphenic acid derivative 2 | 5.32 ± 0.16 a | 4.27 ± 0.17 b | 5.40 ± 0.19 a | 5.41 ± 0.15 a |

| Chestanin | 8.23 ± 0.15 a | 5.94 ± 0.21 b | 8.42 ± 0.54 a | 8.91 ± 0.30 a |

| Isochestanin | 1.87 ± 0.06 a | 1.44 ± 0.18 a | 1.69 ± 0.12 a | 1.93 ± 0.13 a |

| Flavanols | ||||

| (+) Catechin | 2.05 ± 0.28 a | 1.44 ± 0.27 a | 1.31 ± 0.32 a | 1.13 ± 0.26 a |

| Procyanidin pentoside | 2.00 ± 0.18 a | 1.28 ± 0.21 a | 1.59 ± 0.16 a | 1.76 ± 0.25 a |

| Flavonols | ||||

| Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 9.21 ± 0.30 ab | 8.02 ± 0.39 b | 9.80 ± 0.35 a | 9.60 ± 0.38 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 1.41 ± 0.05 a | 1.17 ± 0.14 a | 1.40 ± 0.12 a | 1.32 ± 0.11 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 4.46 ± 0.05 a | 3.66 ± 0.17 b | 4.94 ± 0.18 a | 4.95 ± 0.21 a |

| Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 0.71 ± 0.07 a | 0.46 ± 0.10 a | 0.59 ± 0.08 a | 0.56 ± 0.08 a |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | 0.76 ± 0.03 a | 0.56 ± 0.12 a | 0.78 ± 0.11 a | 0.75 ± 0.10 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide | 2.31 ± 0.05 a | 1.85 ± 0.15 a | 2.19 ± 0.14 a | 2.19 ± 0.16 a |

| Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 1.25 ± 0.02 b | 1.17 ± 0.05 b | 1.49 ± 0.05 a | 1.57 ± 0.07 a |

| Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 1.73 ± 0.04 a | 1.29 ± 0.15 a | 1.67 ± 0.13 a | 1.62 ± 0.18 a |

| Kaempferol-3-O-(6ˇ-O-acetyl)glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside | 1.06 ± 0.04 a | 0.92 ± 0.82 a | 1.11 ± 0.07 a | 1.11 ± 0.09 a |

| Total hydroxycinnamic acids | 1.77 ± 0.13 a | 1.08 ± 0.17 b | 1.21 ± 0.16 ab | 1.40 ± 0.14 ab |

| Total hydroxybenzoic acids | 46.05 ± 1.10 a | 37.53 ± 1.66 b | 46.98 ± 2.17 a | 47.45 ± 1.56 a |

| Total flavanols | 4.01 ± 0.45 a | 2.72 ± 0.48 a | 2.90 ± 0.46 a | 2.89 ± 0.49 a |

| Total flavonols | 22.90 ± 0.50 ab | 19.10 ± 1.33 b | 23.96 ± 1.21 a | 23.66 ± 1.35 ab |

| TAPC | 74.77 ± 2.19 a | 60.43 ± 3.54 b | 75.05 ± 3.52 a | 75.40 ± 3.21 a |

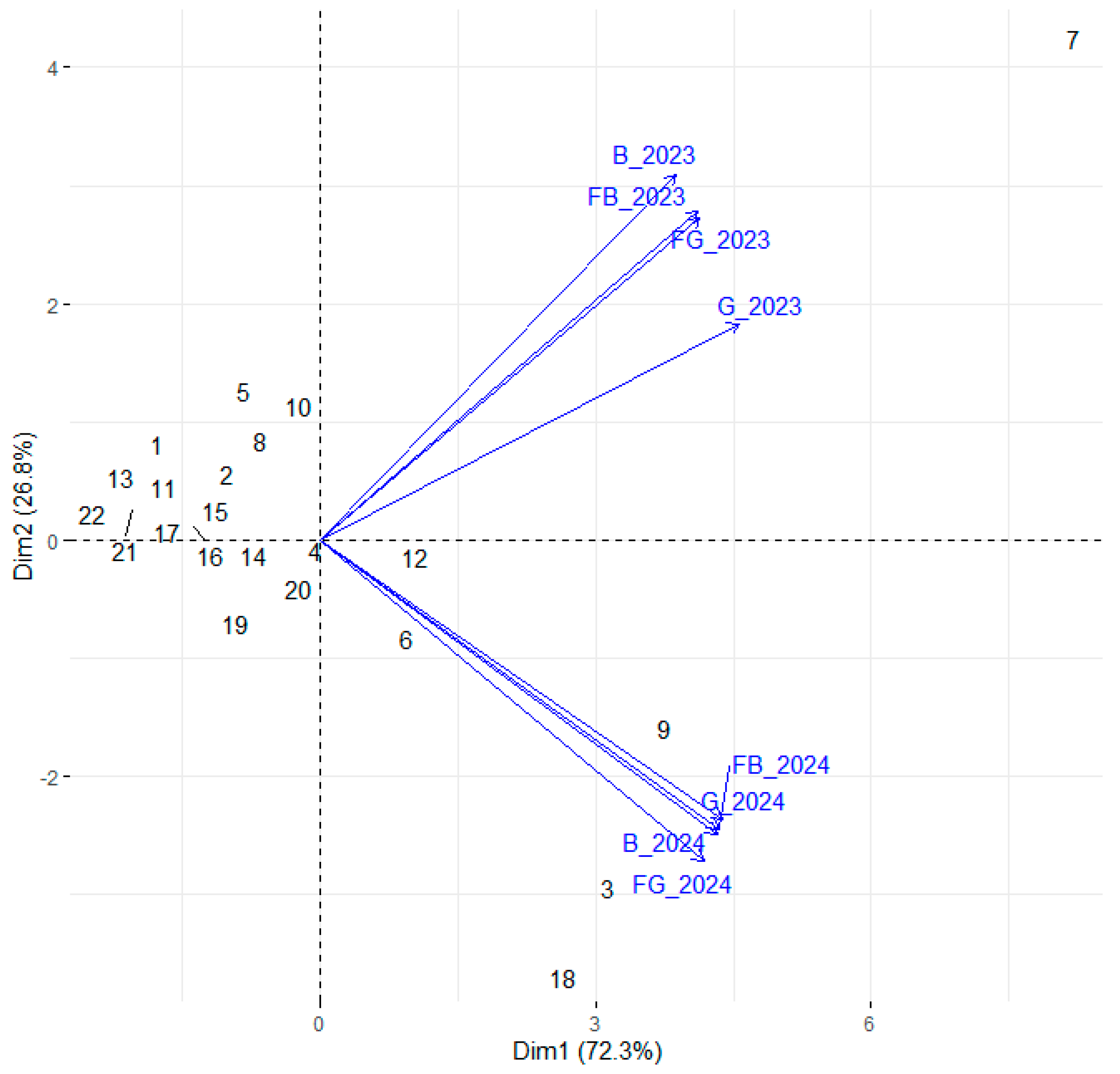

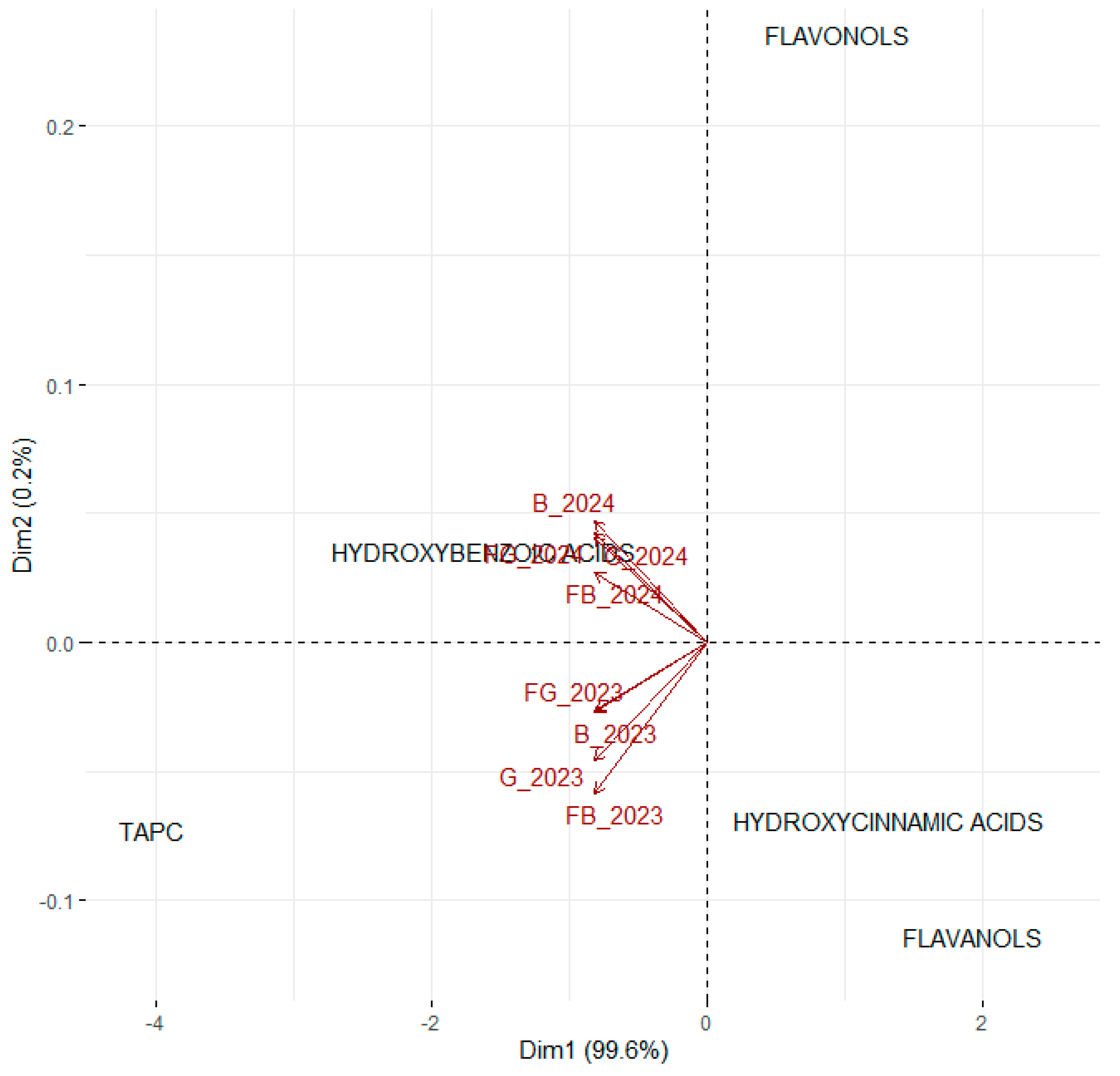

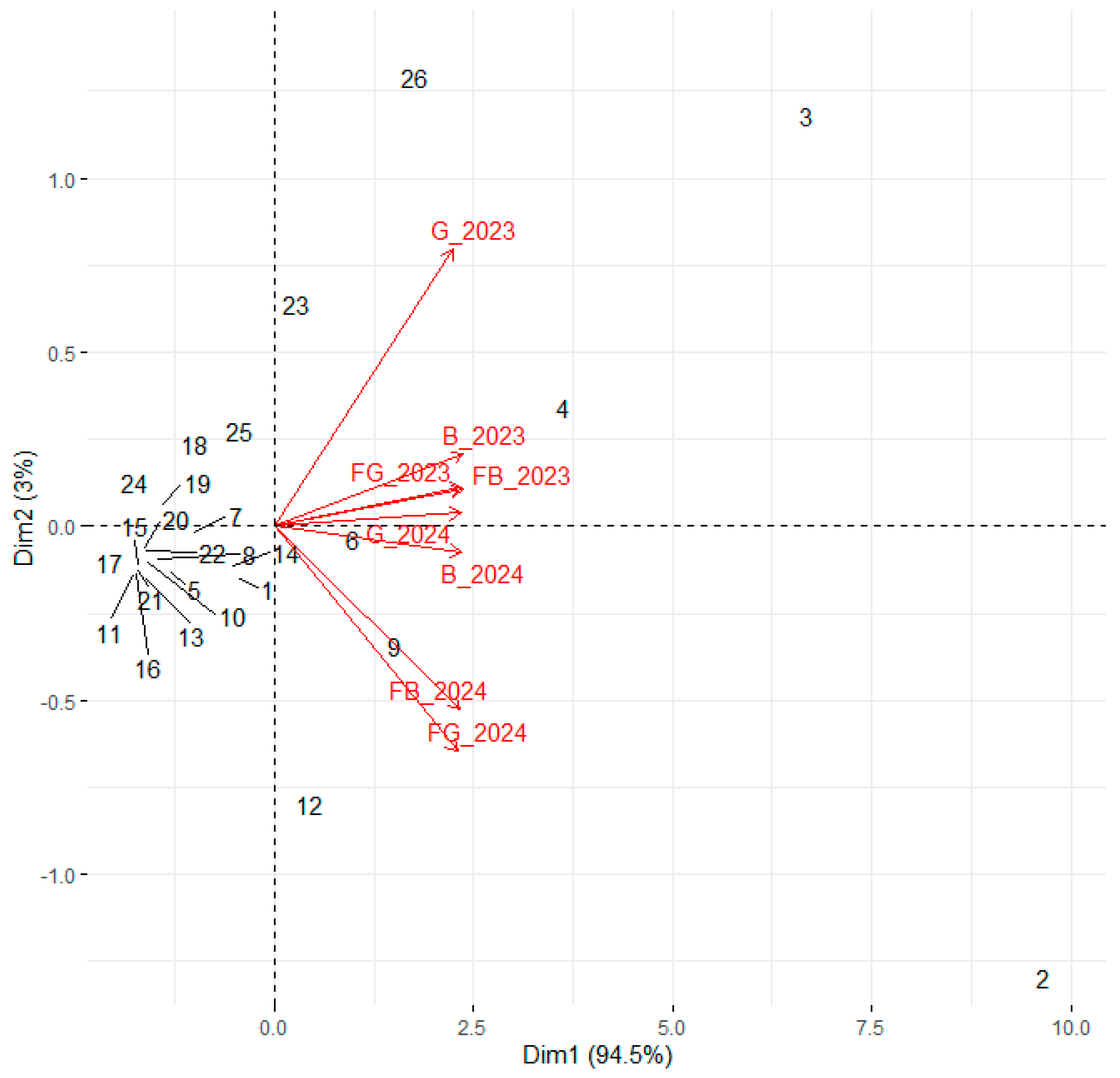

3.4. Taking All Parameters into Account in the First and Second Years After Planting

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prospero, S.; Rigling, D. Chestnut blight. In Infectious Forest Diseases; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Miguélez, M.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Pardos, M.; Madrigal, G.; Ruiz-Peinado, R.; López-Senespleda, E.; Del Río, M.; Calama, R. Development of tools to estimate the contribution of young sweet chestnut plantations to climate-change mitigation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 530, 120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.; Kalcsits, L. Water deficit timing affects physiological drought response, fruit size, and bitter pit development for ‘Honeycrisp’apple. Plants 2020, 9, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasović, P.; Kopıtar, D.; Brunšek, R.; Schwarz, I. The impact of cellulose and PLA biopolymer nonwoven mulches on the soil health. J. Polytech. 2023, 27, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Rafiq, R.; Hussain, M.; Farooq, M.; Jabran, K. Ridge sowing improves root system, phosphorus uptake, growth and yield of maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2012, 22, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11277:2009; Soil Quality—Determination of Particle Size Distribution in Mineral Soil Material—Method by Sieving and Sedimentation. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, A.; Zamljen, T.; Hudina, M.; Veberic, R. Identification and quantification of naphthoquinones and other phenolic compounds in leaves, petioles, bark, roots, and buds of Juglans regia L., using HPLC-MS/MS. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, A.; Kunc, P.; Veberič, R. How storage temperatures shape the metabolic content of selected red and green kiwiberry cultivars. Food Chem. 2025, 48, 144864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medic, A.; Kunc, P.; Zamljen, T.; Hudina, M.; Veberic, R.; Solar, A. Identification and quantification of the major phenolic constituents in Castanea sativa and commercial interspecific hybrids (C. sativa × C. crenata) chestnuts using HPLC–MS/MS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.; Zhou, J.; Guo, J.; Ullah, F.; Hassan, M.; Ara, S.; Ji, C.Y. Comprehensive review for the effects of ridge furrow plastic mulching on crop yield and water use efficiency under different crops. Int. Agric. Eng. J. 2017, 26, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, T.B.; Darouich, H.; Pereira, L.S. Mulching effects on soil evaporation, crop evapotranspiration and crop coefficients: A review aimed at improved irrigation management. Irrig. Sci. 2024, 42, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, H.-R.; Zafar, Z.U.; Ashraf, M. Glycinebetaine improved photosynthesis in canola under salt stress: Evaluation of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters as potential indicators. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2015, 201, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B. Carotenoids and photoprotection in plants: A role for the xanthophyll zeaxanthin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 1990, 1020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mibei, E.K.; Ambuko, J.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Onyango, A.N.; Owino, W.O. Carotenoid profiling of the leaves of selected African eggplant accessions subjected to drought stress. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V.; Lattanzio, V.; Cardinali, A. Role of phenolics in the resistance mechanisms of plants against fungal pathogens and insects. In Trivandrum, Phytochemistry: Advances in Research; Imperato, F., Ed.; Research Signpost: Kochi, India, 2006; pp. 23–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.; Tan, J.; Huo, Z.; Huang, G. Effects of ridge planting on the distribution of soil water-salt-nitrogen, crop growth, and water use efficiency of processing tomatoes under different irrigation amounts. Water 2025, 17, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Hou, H.; Liu, P.; Cai, T.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z.; Ren, X.; Chen, X. Appropriate ridge-furrow ratio can enhance crop production and resource use efficiency by improving soil moisture and thermal condition in a semi-arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezghi, H.; Abay, N.; Yohannes, T. Effect of mulching and/or watering on soil moisture for growth and survival of the transplanted tree seedlings in dry period. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Falco, V.; Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; Silva, A.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Amaral, J.S.; Igrejas, G.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; et al. Evaluation of the phenolic profile of Castanea sativa Mill. by-products and their antioxidant and antimicrobial activity against multiresistant bacteria. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerulli, A.; Napolitano, A.; Hošek, J.; Masullo, M.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Antioxidant and In Vitro preliminary anti-inflammatory activity of Castanea sativa (Italian Cultivar “Marrone di Roccadaspide” PGI) burs, leaves, and chestnuts extracts and their metabolite profiles by LC-ESI/LTQOrbitrap/MS/MS. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurek, N.; Pawłowska, A.M.; Pycia, K.; Potocki, L.; Kapusta, I.T. Quantitative and qualitative determination of polyphenolic compounds in Castanea sativa leaves and evaluation of their biological activities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formato, M.; Vastolo, A.; Piccolella, S.; Calabrò, S.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Zidorn, C.; Pacifico, S. Castanea sativa Mill. leaf: UHPLC-HR MS/MS analysis and effects on In Vitro rumen fermentation and methanogenesis. Molecules 2022, 27, 8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J. Ellagitannins: Biosynthesis, biodegradation and biological properties. J. Med. Plants 2011, 5, 4696–4703. [Google Scholar]

- Treutter, D. Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2006, 4, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Almeida, C.T.D.S.; Morel, M.H.; Terrier, N.; Mameri, H.; Simões Larraz Ferreira, M. Dynamic metabolomic changes in the phenolic compound profile and antioxidant activity in developmental sorghum grains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 1725–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A.; Paiva, N.L. Stress-Induced Phenylpropanoid Metabolism. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: Regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 2008, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Foil | No Foil | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | No Ridge | Ridge | No Ridge | Ridge |

| Basic plant measurements | ||||

| number of shoots/plant | 20.33 ± 2.91 a | 17.17 ± 1.42 ab | 18.71 ± 2.86 a | 15.00 ± 1.75 b |

| number of leaves/plant | 161.83 ± 25.42 a | 167.67 ± 15.57 a | 162.57 ± 28.53 a | 108.33 ± 9.15 b |

| plant height (cm) | 124.67 ± 6.24 ab | 149.83 ± 7.87 b | 119.57 ± 7.48 a | 108.67 ± 6.88 a |

| plant width (cm) | 75.83 ± 3.60 a | 81.33 ± 9.97 a | 71.29 ± 7.45 a | 59.17 ± 5.59 b |

| stem girth (cm) | 7.17 ± 0.48 b | 7.42 ± 0.40 b | 5.43 ± 0.17 a | 4.92 ± 0.20 a |

| Shoot measurements | ||||

| Internode distance (cm) | 1.21 ± 0.09 a | 2.05 ± 0.29 b | 1.29 ± 0.08 a | 1.36 ± 0.11 ab |

| Shoot length (cm) | 13.06 ± 1.32 b | 22.11 ± 3.00 c | 10.54 ± 1.10 a | 14.00 ± 1.50 b |

| Leaf parameters | ||||

| leaf area (cm2) | 29.48 ± 2.29 a | 55.15 ± 5.27 b | 24.27 ± 1.40 a | 21.65 ± 1.11 a |

| leaf lenght (cm) | 10.14 ± 0.53 a | 14.57 ± 0.85 b | 9.33 ± 0.30 a | 9.76 ± 0.30 a |

| leaf width (cm) | 4.80 ± 0.54 ac | 5.31 ± 0.24 c | 3.96 ± 0.16 ab | 3.60 ± 0.13 b |

| leaf perimeter (cm) | 36.57 ± 2.18 a | 50.10 ± 3.06 b | 30.07 ± 1.35 a | 29.58 ± 1.48 a |

| leaf ratio | 2.31 ± 0.13 a | 2.73 ± 0.10 b | 2.42 ± 0.09 ab | 2.76 ± 0.09 b |

| leaf voids | 7.96 ± 1.59 a | 11.03 ± 1.26 a | 8.70 ± 1.34 a | 9.22 ± 1.10 a |

| L* | 24.43 ± 0.22 b | 23.82 ± 0.30 b | 27.72 ± 0.65 a | 27.24 ± 0.68 a |

| a* | −1.43 ± 0.15 b | −1.12 ± 0.17 b | −2.98 ± 0.30 a | −2.32 ± 0.17 a |

| b* | 11.35 ± 0.65 b | 9.60 ± 0.71 b | 16.16 ± 1.35 a | 15.20 ± 0.94 a |

| C* | 11.43 ± 0.65 b | 9.66 ± 0.74 b | 16.42 ± 1.38 a | 15.38 ± 0.95 a |

| h | 97.37 ± 1.08 ab | 96.58 ± 0.57 b | 100.60 ± 0.99 a | 98.92 ± 0.83 ab |

| Leaf chlorophyll content | ||||

| Kl A (μg/mL) | 17.52 ± 2.75 a | 16.66 ± 2.62 a | 9.1 ± 2.32 b | 10.12 ± 0.88 b |

| Kl B (μg/mL) | 11.1 ± 2.09 a | 9.3 ± 1.82 a | 7.26 ± 1.11 b | 6.7 ± 0.86 b |

| Karot (μg/mL) | 3.88 ± 0.3 a | 4.14 ± 0.54 a | 2.07 ± 0.78 c | 2.83 ± 0.27 b |

| Total pigments (μg/mm2) | 1.29 ± 0.2 a | 1.2 ± 0.17 a | 0.73 ± 0.11 b | 0.78 ± 0.07 b |

| Foil | No Foil | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | No Ridge | Ridge | No Ridge | Ridge |

| Basic plant measurements | ||||

| number of shoots/plant | 39.00 ± 5.48 b | 51.83 ± 9.21 c | 23.86 ± 4.10 a | 21.50 ± 2.16 a |

| number of leaves/plant | 383.00 ± 67.74 b | 534.67 ± 83.44 c | 203.14 ± 32.62 a | 186.50 ± 18.30 a |

| plant height (cm) | 175.71 ± 8.96 b | 230.00 ± 7.30 c | 144.71 ± 7.56 a | 150.83 ± 5.83 a |

| plant width (cm) | 133.43 ± 7.29 b | 143.00 ± 7.46 b | 99.71 ± 9.26 a | 111.50 ± 6.06 a |

| stem girth (cm) | 12.79 ± 0.63 b | 14.00 ± 0.86 b | 9.14 ± 0.59 a | 9.33 ± 0.56 a |

| Shoot measurements | ||||

| Internode distance (cm) | 3.78 ± 0.29 a | 4.02 ± 0.23 a | 3.60 ± 0.24 a | 3.44 ± 0.41 a |

| Shoot length (cm) | 28.86 ± 3.43 a | 43.69 ± 6.61 b | 29.36 ± 2.92 a | 27.60 ± 3.26 a |

| Leaf parameters | ||||

| leaf area (cm2) | 56.70 ± 4.56 a | 70.73 ± 3.19 b | 63.06 ± 3.55 ab | 61.61 ± 4.35 ab |

| leaf lenght (cm) | 15.12 ± 0.83 a | 16.99 ± 0.37 a | 16.16 ± 0.49 a | 15.52 ± 0.67 a |

| leaf width (cm) | 5.22 ± 0.21 a | 6.34 ± 0.28 b | 5.56 ± 0.18 ab | 6.12 ± 0.39 ab |

| leaf perimeter (cm) | 91.85 ± 6.40 a | 109.38 ± 3.05 b | 101.27 ± 3.74 ab | 98.44 ± 4.95 ab |

| leaf ratio | 2.88 ± 0.09 a | 2.83 ± 0.11 a | 2.94 ± 0.09 a | 2.68 ± 0.15 a |

| leaf voids | 96.87 ± 7.83 b | 85.72 ± 5.27 ab | 63.32 ± 5.86 a | 66.70 ± 6.59 a |

| Leaf chlorophyll content | ||||

| Kl A (μg/mL) | 6.91 ± 1.24 b | 6.40 ± 1.21 b | 9.47 ± 0.80 a | 5.62 ± 0.98 b |

| Kl B (μg/mL) | 13.93 ± 2.37 b | 12.52 ± 2.98 b | 18.70 ± 1.60 a | 11.28 ± 1.80 b |

| Karot (μg/mL) | 5.51 ± 0.55 ab | 4.45 ± 0.94 b | 6.46 ± 0.04 a | 4.19 ± 0.53 b |

| Total pigments (μg/mm2) | 1.06 ± 0.27 b | 0.97 ± 0.32 b | 1.41 ± 0.11 a | 0.87 ± 0.19 b |

| Compound | Rt (min) | [M-H]- (m/z) | MS2 (m/z) | MS3 (m/z) | MS4 (m/z) | Expressed as | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 1 | 5.84 | 337 | 293 (100) | 169 (100), 167 (77), 123 (7), 125 (2) | 125 (100) | Gallic acid |

| 2 | Gallic acid | 6.40 | 169 | 125 (100) | Gallic acid | ||

| 3 | Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 2 | 11.96 | 337 | 293 (100) | 169 (100), 167 (79), 123 (7), 125 (1) | Gallic acid | |

| 4 | Gallic acid derivative 1 | 12.96 | 337 | 169 (100), 119 (4), 191 (6), 173 (5) | 125 (100) | Gallic acid | |

| 5 | (+) Catechin | 13.38 | 289 | 245 (100), 205 (36), 179 (13), 231 (8) | (+) Catechin | ||

| 6 | Hexahydroxydiphenic acid derivative 1 | 14.37 | 475 | 293 (100), 337 (19), 169 (3) | Gallic acid | ||

| 7 | Cryptochlorogenic acid (4-caffeoylquinic acid) | 14.75 | 353 | 191 (100), 179 (5) | Gallic acid | ||

| 8 | Gallic acid derivative 2 | 16.01 | 477 | 169 (100) | 125 (100) | Gallic acid | |

| 9 | 5-O-p-coumaroylquinic acid | 16.94 | 337 | 191 (100), 173 (15), 163 (7) | Neochlorogenic acid | ||

| 10 | Hexahydroxydiphenic acid derivative 2 | 17.78 | 475 | 293 (100), 337 (19), 169 (2) | Gallic acid | ||

| 11 | Chestanin | 18.15 | 937 | 467 (100), 469 (30), 637 (10), 305 (2) | 305 (100), 261 (73), 260 (41), 243 (29), 304 (23) | Gallic acid | |

| 12 | Procyanidin pentoside | 18.87 | 441 | 330 (100), 331 (74), 289 (38), 161 (11) | 245 (100), 205 (36), 179 (13), 231 (8) | (+) Catechin | |

| 13 | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 20.34 | 609 | 301 (100), 300 (21), 179 (2) | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | ||

| 14 | Isochestanin | 20.85 | 937 | 467 (100), 469 (32) | Gallic acid | ||

| 15 | Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 21.16 | 463 | 301 (100), 300 (23), 179 (1) | Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | ||

| 16 | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | 21.33 | 463 | 301 (100), 300 (17), 179 (1) | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | ||

| 17 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 21.86 | 593 | 285 (100), 357 (3), 229 (2), 284 (2) | 257 (100), 267 (51), 241 (37), 229 (37), 197 (21), 163 (18) | Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | |

| 18 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | 22.02 | 623 | 315 (100), 300 (16), 271 (4), 255 (3) | 299 (100) | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | |

| 19 | Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide | 22.43 | 477 | 301 (100) | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | ||

| 20 | Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 22.82 | 447 | 284 (100), 285 (95), 255 (10), 179 (2) | 255 (100), 256 (30), 227 (10) | Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | |

| 21 | Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 23.01 | 447 | 301 (100), 300 (20), 179 (1) | Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | ||

| 22 | Kaempferol-3-O-(6ˇ-O-acetyl)glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside (Kaempferol-3-O-neohesperidoside acetate) | 24.73 | 635 | 575 (100), 285 (49), 284 (12), 255 (5) | 285 (100), 283 (62), 255 (37), 284 (28) | 257 (100), 267 (45), 241 (38), 229 (34), 197 (20), 163 (18) | Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medic, A.; Grohar, M.C.; Kunc, P. Enhancing Establishment of Young Chestnut Trees Under Water-Limited Conditions: Effects of Ridge Planting and Foil Mulching on Growth, Physiology, and Stress Responses. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121447

Medic A, Grohar MC, Kunc P. Enhancing Establishment of Young Chestnut Trees Under Water-Limited Conditions: Effects of Ridge Planting and Foil Mulching on Growth, Physiology, and Stress Responses. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121447

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedic, Aljaz, Mariana Cecilia Grohar, and Petra Kunc. 2025. "Enhancing Establishment of Young Chestnut Trees Under Water-Limited Conditions: Effects of Ridge Planting and Foil Mulching on Growth, Physiology, and Stress Responses" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121447

APA StyleMedic, A., Grohar, M. C., & Kunc, P. (2025). Enhancing Establishment of Young Chestnut Trees Under Water-Limited Conditions: Effects of Ridge Planting and Foil Mulching on Growth, Physiology, and Stress Responses. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121447