Abstract

Agriculture significantly contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, yet fluxes from irrigated semi-arid systems remain poorly quantified. This study investigates CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 fluxes in a short-term lettuce experiment under semi-arid conditions. The objective was to quantify flux variability and identify key environmental and management drivers. High-frequency soil gas flux measurements were conducted under three treatments: irrigated soil (I), irrigated soil with plants (IP), and irrigated soil with plants plus NH4NO3 fertilizer (IPF). Environmental factors, including solar radiation, soil temperature, water-filled pore space, and relative projected leaf area, were monitored. A Random Forest model identified main flux determinants. Fluxes varied with plant function, growth, and fertilization. IP exhibited net CO2 uptake through photosynthesis, whereas I and IPF showed net CO2 emissions from soil respiration and fertilizer-induced disruption of plant function, respectively. CH4 uptake occurred across treatments but decreased with plant presence. Fertilization in IPF triggered episodic N2O (EF = 0.1%) and NH3 emissions (EF = 0.97%) linked to nitrogen input. Vegetated semi-arid soils can act as CO2 sinks when nitrogen is optimally managed. Excess or poorly timed nitrogen delays CO2 uptake and increases reactive nitrogen losses. Methanotrophic activity drives CH4 dynamics and is influenced by plants and fertilization. Maintaining crop vigor and applying precision nitrogen management are essential to optimize productivity while mitigating GHG and NH3 emissions in semi-arid lettuce cultivation.

1. Introduction

Agriculture significantly contributes to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1,2], with carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) as the primary gases of concern [3]. CO2 emissions and removals are predominantly linked to land-use changes and management practices [4], while CH4 originates mainly from enteric fermentation, manure management, rice cultivation, and agricultural biomass burning. N2O emissions are primarily associated with agricultural soils, manure management, and agricultural biomass burning [2]. Additionally, ammonia (NH3), though not a GHG, is a key component of the nitrogen cycle and indirectly contributes to GHG emissions via microbial conversion to N2O [5]. Accurate monitoring of GHG emissions in agriculture is essential for developing effective climate change mitigation strategies and ensuring compliance with international agreements such as the Paris Agreement [6]. Agricultural systems are highly dynamic, with emissions varying temporally and spatially due to factors like soil type, climate, and management practices [7,8]. Robust monitoring infrastructure is critical for establishing baseline emission levels, evaluating mitigation measures, and supporting evidence-based policy interventions such as low-emission farming incentives and sustainable technology investments [9,10].

The Eastern Mediterranean region, including Cyprus, is characterized by limited and variable precipitation, coupled with prolonged periods of high temperatures, which are expected to intensify with climate change [11]. These conditions suggest that actual GHG emissions are lower than the default values suggested by IPCC protocols, particularly in rain-fed systems [12,13,14,15]. Studies in Mediterranean climates have also demonstrated that N2O emissions were substantially lower than in temperate regions [16], highlighting the need for precise, region-specific GHG measurements. High-temporal-frequency monitoring using automated non-steady-state soil chambers (a-NSS) interfaced with online analyzers allows improved quantification of CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 fluxes, capturing rapid temporal dynamics and enhancing measurement quality [9,17,18,19].

Most previous chamber studies focused on bare soil, often overlooking the influence of vegetation, except in net ecosystem exchange (NEE) studies [20,21]. Recent research integrating vegetation has revealed its significant influences on non-CO2 gases exchange, including CH4 [22,23], N2O [24,25,26], and NH3 [27,28]. Integrating vegetation dynamics into GHG monitoring improves accuracy by capturing plant-soil interactions that affect both emissions and carbon sequestration, aligning with the EU’s goals for net-zero emissions in agriculture while maintaining productivity [29]. Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) is well suited to Mediterranean conditions as an open-field crop and represents an important cash crop both in the region as well as in Cyprus [30,31,32]. In this study, it was also selected as a model crop because its compact size and morphology fit well within the automated soil chambers, allowing the creation of a stable vegetated soil system for GHG and NH3 measurements. The primary objective of this study is to investigate greenhouse gas fluxes from irrigated semi-arid vegetated agricultural soils. We aim to quantify the instantaneous and diel fluxes of CO2, N2O, CH4, and NH3 and explore their relationships with key environmental and management factors. By combining state-of-the-art monitoring techniques with current scientific knowledge, this work contributes to optimizing climate change mitigation strategies and improving crop management practices in semi-arid agricultural systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site & Experimental Setup

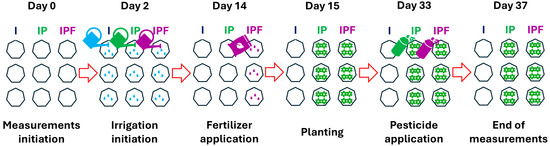

The experiment was conducted at the Agricultural Research Institute of Cyprus, situated in the Athalassa area of Lefkosia, Cyprus (35°08′25″ N–33°23′02″ E, elevation 170 m above sea level) during the late Spring–Summer period from 18 May to 24 June 2022 [9]. Nine transparent soil a-NSS chambers (eosAC-LT, Eosense, Inc., Dartmouth, NS, Canada) were established (Figure 1) in an experimental field plot measuring 3 × 18 m following shallow soil tillage to a depth of approximately 25 cm. Irrigation commenced two days after the chambers’ installation on 20 May 2022 (Figure 1), with an initial addition of 10 L (48 mm) of water per chamber. Subsequently, an average of 13 L (62 mm) per week was added to each chamber until the termination of GHG measurements. Fourteen days after setting up the chambers, each of the three randomly selected chambers received an irrigation application of 30 g (≈500 kg N ha−1) of NH4NO3 fertilizer (4 L per chamber; Figure 1). Even though NH4NO3 is widely used in horticulture [33], in this study, NH4NO3 exceeds typical agronomic recommendations for lettuce [34,35] to ensure detectable gaseous responses under high-frequency flux monitoring, as recommended for emission factor estimation studies [36]. Following fertilizer application, four romaine lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. longifolia) plantlets, sourced from a local nursery with commercially available seeds, were planted in each of the three chambers that had received the NH4NO3 treatment (Figure 1). Additionally, three chambers were planted with lettuce without fertilizer treatment (Figure 1). This established three different treatments: irrigated soil (I), irrigated soil covered by plants (IP), and irrigated soil covered by plants with fertilizer application (IPF). Mealybugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) infested the plants, and on day 33 after chamber setup, they were promptly treated with acetamiprid (0.25 g per L Mospilan® 20SG; Figure 1). The soil was classified as a Leptic Calcisol [37] with a clay loam texture at approximately 15 cm depth. The soil organic carbon was 5 ± 0.52 g kg−1 (mean ± sd) and the average soil C/N ratio was 8.11 (sd = 2.11). Soil pH remained alkaline and ranged from 7.5 to 8.5 across measurement dates (Figure S3c).

Figure 1.

Chronological overview of experimental events, including initiation of measurements, irrigation, fertilizer and pesticide applications, planting, and termination of measurements. The three treatments were: irrigated soil only (I), irrigated soil with plants (IP), and irrigated soil with plants plus fertilizer (IPF), with three chambers assigned to each treatment.

2.2. Monitoring GHG Fluxes

During the period of 18 May to 24 June 2022, surface soil fluxes of CO2, CH4, N2O and NH3 were consistently measured using an a-NSS chamber sampling system. The sampling system comprised the nine a-NSS chambers, connected to a cavity ring-down spectrometer (CRDS; G2509, Picarro Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) via a recirculating multiplexer (eosMX, Eosense Inc.). The CRDS continuously monitored CO2, CH4, N2O and NH3 concentrations within each chamber and the eosMX operated by eosLink-MX_v1.9.14 software (Eosense Inc.) managed sequential chamber closure and gas measurement. The a-NSS chambers were placed in a completely randomized design, with a minimum separation of at least 1 m between each chamber.

Data from the CRDS were collected at an average frequency of every 1 s, presented as dry mole fractions in parts-per-million (ppm) (e.g., CO2, CH4, and N2O) or parts-per-billion (ppb) (e.g., NH3). Chamber deployment involved a 5 min closure period complemented by a 45 s valve pre-delay and a 90 s valve post-delay. Each a-NSS chamber typically generated an average of 16 measurements every 24 h.

Soil fluxes were estimated for each gas by first fitting a shape-constrained additive model (SCAM) to the gas concentration (C in ppm) vs. time (t in seconds) curves and subsequently approximating its derivative at time 0 by using finite differences as described in Themistokleous et al. [9]. The estimate of was then multiplied by the ratio of the total system volume (V, 0.077957 m3) to the chamber surface area (A, 0.21 m2) to obtain the raw flux rate (F, in ppm m s−1) using Equation (1):

To account for the volume component of the lettuce growing inside each chamber, the volume of lettuce was first estimated and then subtracted from the total system volume [9]. Finally, the raw flux rate was corrected for the effects of air temperature inside the chamber (T; K), chamber pressure (P; Pa), and the water content of the initial gas sample drawn from the chamber (W; mole fraction × 100) using the Ideal Gas Law [38,39] and ideal gas constant (R, 8.314 m3 Pa K−1 mol−1) to obtain the corrected flux rate (FC, in μmol m−2 s−1) using Equation (2):

After instantaneous flux (i.e., measurements taken from each chamber closure) computation, the curve area of gas flux vs. time over a 24 h basis is estimated, yielding diel (net) fluxes. Area integration relied on Simpson’s one-third formula adjusted for uneven intervals [40] with a constant (rectangular) area assumed at the start and end of the curve by using the flux values closest to the start and end of the day, respectively. Subsequently, the diel fluxes were summed across consecutive days to obtain cumulative fluxes for each day. This cumulative approach provided a clear representation of the variation in diel fluxes throughout the experimental period, as well as the net exchange for each gas at the end of the measurement period. Net exchange for each gas per treatment provided the net amount of carbon, for CO2 and CH4, or nitrogen, for N2O or NH3, emitted to (positive values) or removed from the atmosphere (negative values) overall during the experimental period. The N2O and NH3 net exchange values obtained for IP (i.e., control) and IPF (i.e., fertilizer application) treatments were then used to obtain the emission factors (EFs) for N2O and NH3, respectively. Emission factors represent the percentage of the nitrogen applied as a given nitrogen source (e.g., fertilizer) that is emitted as N2O or NH3 over a specified period [41]. EF in single experiments is calculated by subtracting the net emissions (e.g., mg N2O-N m−2) occurring in a control treatment where no nitrogen is added from the net emissions (e.g., mg N2O-N m−2) in a given experimental treatment where nitrogen was added, then dividing this by the amount of nitrogen applied (e.g., mg N m−2) [41].

The net carbon exchange values considering the overall experimental period for CO2 were converted to NEE values (g CO2 m−2) whereas the net carbon exchange values for methane (CH4) and the net nitrogen exchange values for nitrous oxide (N2O) were converted into carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) based on the Global Warming Potential (GWP) values established in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) [42]. The GWP values for CH4 and N2O from the AR6 are 27 and 273, respectively, over a 100-year time horizon [42]. This conversion process was essential for standardizing and comparing the impacts of different GHGs in terms of their potential to contribute to global warming. By applying these GWP values, CO2e for each gas species was calculated based on their respective emissions data. For instance, to convert diel fluxes and net exchange values into CO2e, the mass of each gas emitted was multiplied by its GWP: CO2e = Mass of CH4 × 27, and CO2e = Mass of N2O × 273. This approach facilitates not only a clearer understanding of overall greenhouse gas emissions but also aids in comparing the climate impact of different gas species over time.

2.3. Ancillary Measurements

The projected plant leaf area, derived from zenithal images, was quantified during the experiment using red, green, and blue (RGB) imaging and image analysis with the freeware ImageJ 1.54g [43] as described by Savvides et al. [44,45]. Projected plant leaf area was converted to relative projected plant leaf area (rPLA), i.e., the percentage of soil surface covered by the projected leaf area, by dividing PLA by the chamber soil surface area and multiplying the result by 100. The images were taken on days 15 (lettuce plantation), 22, 29, and 36 (2 days prior to experiment termination).

To investigate the influence of soil chemical properties on GHG fluxes, three soil samples per treatment were acquired every 5 days, starting from day 15 (lettuce planting) up to day 40 (post experiment). Soil samples were collected from small circular plots established adjacent to each chamber (<1 m) and subjected to the same treatment practices, to replicate the chamber conditions while avoiding disturbance. The soil samples were obtained by pushing a 50 mL Falcon tube to a depth of 15 cm into the soil from the surface. The samples were then placed in a plastic bag and transported to a nearby laboratory (~3 min) for immediate processing. The soil was air-dried and sieved to 2 mm Ø. Soil NH4+-N and NO3−-N concentrations were determined with a continuous flow analyzer (SAN++® Series, Skalar Analytical B.V., Breda, The Netherlands) after extracting them from moist soil using a 0.2 M KCl solution (soil:solution = 1:10 w/v) [46,47]. Soil pH was directly measured with a pH-EC meter (HI-5522, Hanna Instruments Ltd., Leighton Buzzard, UK) at a 1:1 (w/v) soil to water ratio. Soil organic matter was determined with the Walkley & Black chromic acid wet oxidation method [48]. The soil hydrometer method [49] was used to assess soil particle size distribution. Soil texture class was determined by using the USDA soil texture triangle.

To monitor soil volumetric water content and soil temperature (Tsoil), a Teros 11 sensor (METER Group, Pullman, WA, USA) was vertically installed (10 cm soil depth) in each chamber. Soil dry bulk density was determined by extracting four undisturbed soil cores (5 cm diameter × 5 cm height) to 15 cm depth using a ring sampler (A53, Royal Eijkelkamp, Giesbeek, The Netherlands), evenly spaced across the 3 × 18 m experimental area after shallow tillage. Soil cores were oven-dried, and dry bulk density was calculated as dry mass divided by ring volume. If cores shrank below ring height during drying, volume was corrected accordingly. Soil porosity was then estimated with Equation (3) [50], assuming a soil particle density of 2.65 g cm−3.

The average porosity across all samples was 48.81%. Soil water-filled pore space (WFPS) was then approximated with Equation (4) [50]

Hourly solar radiation (Rsolar) data for the experimental period were obtained from the Meteorology Department of the Republic of Cyprus through a weather station located within proximity to the site (approximately 1 km). Vegetation Activity Index (VAI) was calculated as the product of rPLA and Rsolar (i.e., rPLA × Rsolar). It served as a first-order approximation of the instantaneous biological activity of the plant canopy, assuming that vegetation processes, such as photosynthesis, scale positively with both canopy cover and available light energy.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses followed a structured workflow designed to address different types of data and research questions. First, soil chemical variables and rPLA were evaluated using repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), ensuring model assumptions were tested and, where necessary, addressed through transformations or non-parametric approaches. Next, temporal patterns in daily means of soil temperature, WFPS, and gas fluxes were captured with non-linear Generalized Additive Models (GAMs). To identify the main environmental drivers of gas fluxes, we employed Random Forest models with permutation-based feature importance and ICE plots. Finally, pairwise correlations among variables were assessed using Kendall’s tau.

Statistical analyses were performed in R [51] with the corresponding functions used shown in parentheses. Soil chemical variables and rPLA were analysed using two-factor repeated measures ANOVA (treatment × time), after testing for normality (shapiro.test), homogeneity of variance (levene_test), homogeneity of covariance (box_m), outliers (identify_outliers), extreme skewness (>3) and kurtosis (>10). If assumptions were met, an ANOVA (anova_test) test was applied, followed by pairwise t-tests (pairwise_t_test). If the ANOVA assumptions were not satisfied, the data were Box-Cox transformed Wickham (powerTransform); if assumptions remained unmet, rank-based non-parametric ANOVA (bwrank [52]) was used. Significant effects were followed by pairwise comparisons (spmcpa, spmcpb, spmcpbA [52]).

Daily mean soil temperature, WFPS, and GHG fluxes were analysed using non-linear GAM-based pairwise comparisons [53], selecting the basis dimension (k) with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC [54]), from k = 1 to 40. The level of significance (α) was set at α = 0.05, with false discovery rate controlled by using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg [55]. All graphical outputs were produced using the “ggplot2” package [56].

To identify key drivers of GHG and NH3 fluxes, a Random Forest (RF) model [57] was fitted to each time series (n = 5435). Predictor variables included VAI, Tsoil, WFPS, and days after N fertilization (DAF). Variable importance was evaluated with permutation-based methods, and one-dimensional individual conditional expectation (ICE) plots were used to visualize predictor effects. Full details of the analysis can be found in Supplementary File S1.

The correlation between each variable pair was assessed with Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient (tau) by using the function “cor” from the stat package [51]. The correlation matrix was visualized using the function “corrplot” from the corrplot package [58].

3. Results

3.1. Soil and Plant Traits

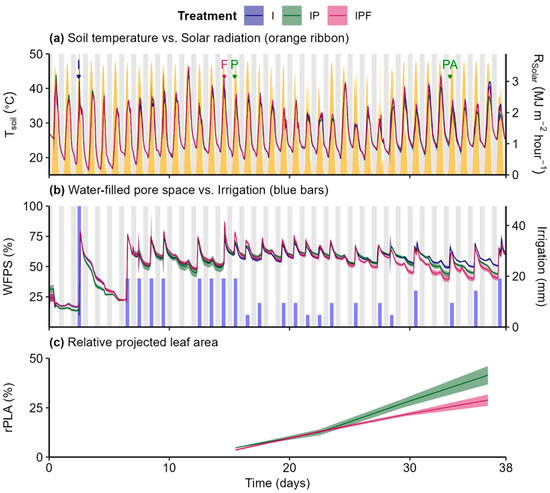

Instantaneous TSoil fluctuated throughout the day (Figure 2a), primarily reflecting Rsolar levels. Overall, Tsoil differences between the treatments were small daily and not statistically significant (Figure S1(a.1–a.3)). Instantaneous WFPS peaked shortly after each irrigation event and gradually decreased with time (Figure 2b), with variation driven mainly by soil water dynamics and plant uptake. Like TSoil, daily differences in WFPS between the treatments were minor and non-significant (Figure S1(b.1–b.3)).

Figure 2.

Instantaneous soil temperature (a), instantaneous water-filled pore space (b), and relative projected leaf area (c) derived from soils (non- or vegetated) in the “I” (Irrigation), “IP” (Irrigation + Plants), and “IPF” (Irrigation + Plants + Fertilizer) treatments. Lines represent the medians (±standard error for the median estimated using bootstrap (B = 999), n = 3). Arrows in plot a indicate when a significant event took place, with the letters “I”, “F”, “P”, and “PA” meaning, respectively, “Irrigation”, “Fertilizer”, “Planting”, and “Pesticide Application”. Grey bars represent the night period, white bars represent the day period, yellow ribbon represents the solar radiation (a) and blue bars the irrigation (b).

The rPLA gradually increased with time in both treatments (Figure 2c), with a greater rate in the IP treatment compared to the IPF treatment despite fertilizer application (Figure S2a). Significant interaction effects were found between treatment and time (Figure S2b) for rPLA, with the IP treatment being like the IPF treatment on days 12 and 22 but significantly larger on days 29 and 36, suggesting slower lettuce growth rates in the IPF treatment.

Soil NH4+-N concentrations were similar between the I and IP treatments (Figure S3a) but higher in the IPF treatment. Significant interaction effects were detected between treatment and time (Figure S3a), with no differences between the I and IP treatments and significant differences with the IPF treatment after day 15. Soil NO3−-N (Figure S3b) concentrations were similar between all treatments. Only a significant time effect was detected (Figure S3b) with soil NO3−-N concentrations declining over time. Soil pH (Figure S3c) showed a transient increase from days 15 to day 20, followed by a gradual decline. Similar to soil NO3−-N concentration, only significant time effects were detected with no treatment or interaction effects (Figure S3c).

3.2. GHG and NH3 Fluxes

3.2.1. Carbon Dioxide

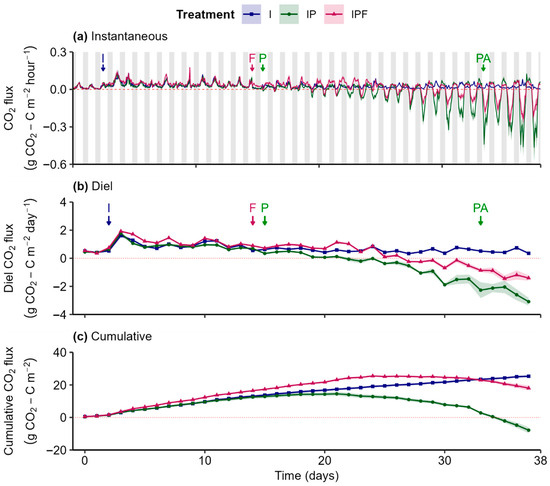

Before treatments’ initiation (day 14, i.e., fertilizer application and planting), instantaneous soil CO2 (net) effluxes (i.e., positive fluxes) exhibited consistent diel oscillations and midday peaks across all treatments, reflecting typical soil respiration patterns (Figure 3a,b). An increase in CO2 efflux was observed immediately after the first irrigation event (day 2), before stabilizing in the subsequent period.

Figure 3.

Instantaneous (a), diel (24 h; (b)), and cumulative (c) CO2 fluxes from soils with different treatments: “I” = Irrigation, “IP” = Irrigation + Plants, and “IPF” = Irrigation + Plants + Fertilizer. Lines represent the gas flux medians, with shaded ribbons showing the standard error of the median estimated using bootstrap (B = 999, n = 3). Arrows mark key events: “I” = Irrigation, “F” = Fertilizer, “P” = Planting, and “PA” = Pesticide Application. Grey bars represent the night period, and white bars represent the day period.

Minor but statistically significant differences were detected between treatments during this pre-treatment period, likely due to inherent soil variability (Figure 3b and Figure S4(a.2,a.3)). Between days 3 to 9, diel (net) CO2 effluxes in the IPF treatment were significantly (p < 0.05) larger compared to the I treatment (Figure 3b and Figure S4(a.1)). In addition, diel CO2 effluxes were significantly lower in the IP treatment compared to the IPF treatment (Figure 3b and Figure S4(a.3)), starting from day 5 and persisting throughout the pre-planting period. The continuous diel effluxes during the pre-planting period resulted in a stable increase in cumulative efflux across treatments, with the highest values observed in the IPF treatment, followed by the I and IP treatments (Figure 3c).

After lettuce planting, treatment had a substantial impact on CO2 dynamics. In the absence of plants (I), instantaneous CO2 fluxes maintained the same trend as observed prior to planting. In contrast, the presence of plants in both IP and IPF treatments induced diel patterns of CO2 influx during the day and efflux during the night (Figure 3a). This pattern intensified over time, particularly in the non-fertilized treatment (IP), which showed a stronger net influx compared to the treatment where fertilizer was applied (IPF). It is worth noting that after fertilizer application (day 15) and until day 24, night CO2 efflux in IPF was obviously higher than in I and IP treatments. Thereafter and until the end of the experiment, night CO2 efflux in IP and IPF was noticeably higher than in the I treatment.

As a result of the observed instantaneous fluxes, the IP treatment exhibited significantly different diel CO2 fluxes compared to the I treatment from days 18 to 37 (Figure S4(a.1)), driven by a shift from diel (net) effluxes to influxes (Figure 3b). In contrast, diel CO2 effluxes in the IPF treatment were significantly larger than those in the I treatment between days 16 to 22 (Figure S4(a.2)). However, as plant development progressed, CO2 uptake gradually became dominant in IPF treatment as well (Figure 3b,c). From days 27 to 38, the IPF treatment again diverged significantly from the I treatment, but now due to an increasing influx. Despite this shift, IPF consistently exhibited smaller diel CO2 influxes than IP throughout the post-planting period.

The increasing diel influxes during the post-planting period in both IP and IPF resulted in a reduction in cumulative CO2 efflux across the two treatments, with the greatest reduction rate observed in the IP treatment (Figure 3c). Conversely, cumulative efflux continued to increase in the I treatment during the post-planting period. Consequently, the net CO2 exchange in the IP treatment was negative, indicating net CO2 removal, and significantly different compared to I and IPF treatments, which showed positive net CO2 exchange and therefore, net CO2 emissions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean (±SEM, n = 3) net gas exchange rates of CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 during the experimental lettuce cultivation across three treatments and the emission factors for N2O and NH3 derived from fertilizer application in IPF. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between the three treatments and number in parentheses indicate the standard error of the mean.

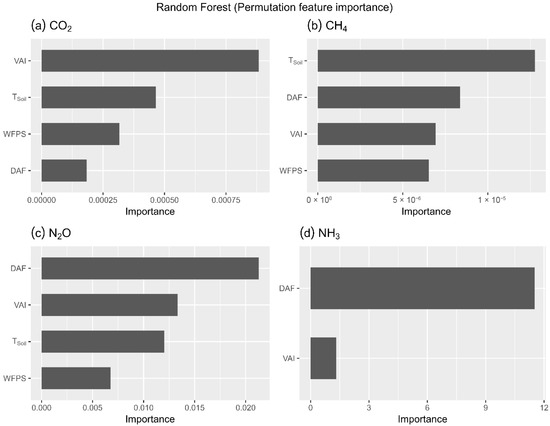

The RF model fitted for CO2 instantaneous fluxes had an OOB coefficient of determination (r2) value of 0.61. The most influential predictor was VAI (47.78%), followed by Tsoil (25.16%), WFPS (17.13%), and DAF (9.93%; Figure 4a). ICE plots revealed that increasing VAI strongly increased net CO2 influx (Figure S5(a.1)). Tsoil had a positive effect on CO2 efflux between 29 and 35 °C (Figure S5(a.2)) before stabilizing. WFPS had the strongest positive effect on CO2 efflux between 30% and 60% (Figure S5(a.3)), while DAF showed a notable positive effect on CO2 efflux (Figure S5(a.4)) until day 9 after fertilizer application, with the declining importance of fertilization thereafter.

Figure 4.

Permutation-based feature importance for greenhouse gas fluxes derived from random forest analysis. Barplots illustrate the feature importance of predictors for CO2 (a), CH4 (b), N2O (c) and NH3 (d). VAI = Vegetation Activity Index, Tsoil = Soil temperature, WFPS = Water-filled pore space, DAF = Days after fertilization.

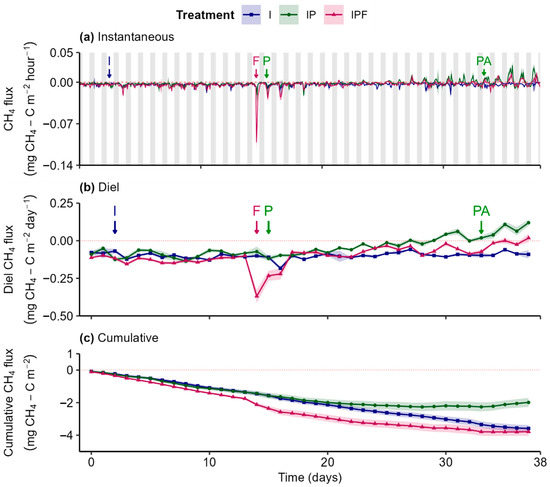

3.2.2. Methane

Net CH4 soil influx was observed in all treatments for most of the experiment (Figure 5a,b). No significant differences in diel fluxes were detected between treatments before fertilizer application on day 14 (Figure S4(b.1–b.3)). The application of fertilizer on day 14 triggered a sharp, within-day increase in CH4 influx in the IPF treatment (Figure 5a), which declined rapidly and was followed by diel oscillations. This transient response resulted in a substantial increase in CH4 influx in the IPF treatment compared to both I and IP treatments from days 14 to 17 (Figure 5b and Figure S4(b.2,b.3)). As a result, cumulative CH4 flux in the IPF treatment shifted more strongly in the negative direction, indicating greater overall CH4 uptake (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Instantaneous (a), diel (24 h; (b)), and cumulative (c) CH4 fluxes from soils with different treatments: “I” = Irrigation, “IP” = Irrigation + Plants, and “IPF” = Irrigation + Plants + Fertilizer. Lines represent the gas flux, with shaded ribbons showing the standard error of the median estimated using bootstrap (B = 999, n = 3). Arrows mark key events: “I” = Irrigation, “F” = Fertilizer, “P” = Planting, and “PA” = Pesticide Application. Grey bars represent the night period, and white bars represent the day period.

Following fertilizer application and lettuce planting, CH4 influx declined over time in the plant-containing treatments, with a shift to net efflux, particularly in IP treatment toward the end of the experiment (Figure 5a,b). This resulted in significant differences for both the IP (days 16 to 38) and IPF (days 35 to 38) treatments compared to the I treatment (Figure S4(b.1,b.2)). Additionally, CH4 effluxes were significantly larger in the IP treatment compared to the IPF treatment towards the latter period of the experiment (days 27 to 38; Figure S4(b.3)).

The treatment-dependent changes in diel CH4 fluxes translated into distinct cumulative exchange patterns. In the IPF treatment, an initial enhancement in CH4 uptake, following fertilizer application, declined during the post-planting period, resulting in no statistically significant difference in net CH4 exchange relative to the I treatment (Table 1). Conversely, the progressive decline in CH4 influx and transition to net efflux in the IP treatment led to a significantly lower net CH4 removal compared to both I and IPF (Table 1).

The RF model fitted for CH4 instantaneous fluxes had an OOB coefficient of determination (r2) value of 0.42. Permutation-based feature importance ranked Tsoil (36.88%) as the top predictor, followed by DAF (24.19%), VAI (20.04%), and WFPS (18.89%) (Figure 4b). ICE plots showed that Tsoil had an increasingly positive effect on CH4 influx above 29 °C (Figure S5(b.1)) and the fertilizer application had an immediate positive effect on CH4 influx, reaching maximum after 2 days, before gradually stabilizing (Figure S5(b.2)). On the other hand, VAI had a negative effect on CH4 influx (Figure S5(b.3)). WFPS had a mild positive effect on CH4 influx that increased sharply above 75% (Figure S5(b.4)).

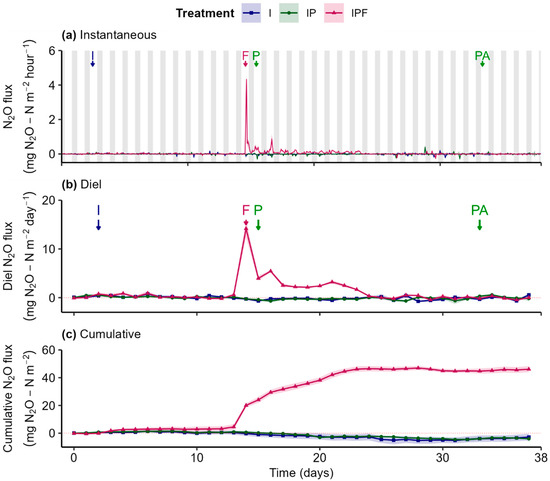

3.2.3. Nitrous Oxide

Soil N2O fluxes generally fluctuated around zero across all treatments throughout the experiment (Figure 6a,b). However, the application of fertilizer on day 14 in the IPF treatment caused a notable within-day peak, marking an episodic increase in N2O efflux (Figure 6a,b). This increase in instantaneous efflux sharply diminished within the same day and gradually declined, exhibiting diel oscillations in the following days. Significant differences were observed in diel fluxes between the IPF treatment and both the I and IP treatments from days 14 to 24 (Figure S4(c.2,c.3)), while no differences were detected between the I and IP treatments during this period (Figure S4(c.1)).

Figure 6.

Instantaneous (a), diel (24 h; (b)), and cumulative (c) N2O fluxes from soils with different treatments: “I” = Irrigation, “IP” = Irrigation + Plants, and “IPF” = Irrigation + Plants + Fertilizer. Lines represent the gas flux medians, with shaded ribbons showing the standard error of the median estimated using bootstrap (B = 999, n = 3). Arrows mark key events: “I” = Irrigation, “F” = Fertilizer, “P” = Planting, and “PA” = Pesticide Application. Grey bars represent the night period, and white bars represent the day period.

The fertilizer-induced increase in diel efflux in the IPF treatment, contrasted with the near-zero fluxes observed in the I and IP treatments, resulted in net emissions (Figure 6c). Cumulative N2O efflux in IPF treatment increased sharply following fertilizer application up to day 24, after which it remained constant until the end of the experiment. This increase led to substantial N2O emissions from the IPF treatment, in contrast to near-zero net exchange in the other two treatments (Table 1). The N2O EF was calculated at 0.1% (Table 1), indicating that 0.1% of the applied nitrogen was emitted as N2O throughout the experiment.

The RF model fitted for Ν2O instantaneous fluxes had an OOB coefficient of determination (r2) value of 0.47. Permutation-based feature importance (Figure 4c) ranked DAF (39.87%) as the dominant predictor, followed by VAI (25.00%), Tsoil (22.50%), and WFPS (12.64%). ICE plots showed a positive response of Ν2O efflux to DAF reaching its maximum after 2 days, before gradually stabilizing (Figure S5(c.1)). VAI did not exhibit a response on Ν2O flux (Figure S5(c.2)). Tsoil (Figure S5(c.3)) and WFPS (Figure S5(c.4)) had a positive effect on Ν2O beyond 38 °C and 75%, respectively.

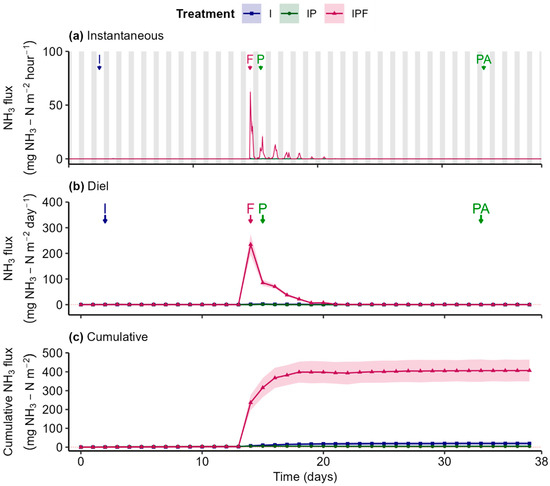

3.2.4. Ammonia

Similar to N2O, soil NH3 fluxes in the I and IP treatments generally fluctuated around zero throughout the experiment (Figure 7a,b). In contrast, the application of fertilizer on day 14 in the IPF treatment triggered a sharp within-day spike in NH3 efflux (Figure 7a,b). This increase in instantaneous efflux rapidly declined within the same day and was followed by low-intensity diel oscillations over the subsequent days.

Figure 7.

Instantaneous (a), diel (24 h; (b)), and cumulative (c) NH3 fluxes from soils with different treatments: “I” = Irrigation, “IP” = Irrigation + Plants, and “IPF” = Irrigation + Plants + Fertilizer. Lines represent the gas flux, with shaded ribbons showing the standard error of the median estimated using bootstrap (B = 999, n = 3). Arrows mark key events: “I” = Irrigation, “F” = Fertilizer, “P” = Planting, and “PA” = Pesticide Application. Grey bars represent the night period, and white bars represent the day period.

On the day prior to fertilizer application (day 13), NH3 diel efflux in the IPF treatment was significantly smaller compared to both the I and IP treatments (Figure S4(d.2,d.3)). Following fertilizer application on day 14, NH3 diel efflux in the IPF treatment increased substantially (Figure 7b,c) resulting in significant differences compared to the other two treatments from days 14 to 19 (Figure S4(d.2,d.3)). Similarly to N2O, no significant differences in NH3 diel fluxes were detected between the I and IP treatments throughout the experiment (Figure S4(d.1)).

The fertilizer-induced rise in diel efflux in the IPF treatment, compared to the near-zero fluxes in the I and IP treatments, led to corresponding changes in cumulative emissions (Figure 7c). Cumulative NH3 flux in the IPF treatment increased sharply and stabilized after day 19, while I and IP treatments exhibited ΝH3 net exchange close to zero. This resulted in substantial NH3 emissions from the IPF treatment, with an estimated EF of 0.97% indicating that 0.97% of the applied nitrogen was emitted as NH3 throughout the experiment (Table 1).

The RF model fitted for NH3 had an OOB coefficient of determination (r2) value of 0.80. Permutation-based feature importance (Figure 4d) identified DAF (89.79%) as the dominant factor, with VAI importance being much smaller (10.21%). ICE plots showed that the addition of fertilizer (Figure S5(d.1)) had an early positive response on NH3 efflux, creating 2 peaks centered on days 1.5 and 4 after fertilizer addition, followed by stabilization after day 6. In contrast, VAI did not exhibit a response to NH3 fluxes (Figure S5(d.2)).

3.2.5. Net GHG Exchange and Global Warming Potential

At the end of the lettuce growing period, net GHG exchange (Table 1), NEE, and GWP (Table 2) varied significantly across treatments, reflecting the influence of plant presence and fertilizer application. The IP treatment acted as a net CO2 sink (Table 1), with negative NEE (Table 2), in contrast to the I and IPF treatments, which exhibited positive net CO2 exchange, and thus positive NEE. CH4 fluxes were negative across all treatments, indicating net uptake, though this was reduced in the IP treatment compared to the I and IPF treatments (Table 1). Despite these differences, CH4 contributed negligibly to the GWP in comparison to N2O, which dominated the global warming potential, particularly in the IPF treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (±SEM, n = 3) net ecosystem exchange (NEE), and the global warming potential (GWP) of CH4 (1 g of CH4 is equivalent to 25 g CO2 equivalents) and N2O (1 g of N2O is equivalent to 273 g CO2 equivalents) during the experimental lettuce cultivation across three treatments. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between the three treatments, and numbers in parentheses indicate the standard error of the mean.

Fertilizer application in the IPF treatment resulted in substantial N2O emissions, significantly higher than the near-zero exchange in the I and IP treatments (Table 2), underscoring the episodic yet impactful nature of N2O emissions on GWP (Table 2). Similarly, NH3 emissions were significantly elevated in the IPF treatment following fertilization, while the I and IP treatments showed negligible fluxes.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 fluxes exhibit distinct patterns depending on the presence, growth, and function of plants and fertilizer application. The IP treatment functioned as a net CO2 sink, with plant photosynthesis outweighing autotrophic and soil heterotrophic respiration (Figure 3 and Table 1). In contrast, the I and IPF treatments exhibited net CO2 emissions, driven by soil or vegetated soil respiration and, in the case of IPF, fertilizer application stimulation effect. CH4 fluxes revealed net uptake in all treatments, but the IP treatment showed reduced influxes, likely influenced by plant-induced effects (Figure 5 and Table 1). Fertilizer application in the IPF treatment caused marked, short-lived increases in N2O and NH3 emissions, underscoring the episodic nature of nitrogen-driven GHG emissions. Among all gases, N2O contributed substantially to the GWP, particularly for the IPF treatment, where it offset gains from CO2 uptake.

4.1. CO2 Dynamics

The CO2 dynamics observed in this study (Figure 3) highlight the complex interplay between plant canopy development and physiological function, soil and aerial conditions, and management practices. The Random Forest analysis identified VAI as the strongest predictor, underscoring the dominant role of plant canopy development and light interception in regulating NEE. This finding is consistent with the shift from diel efflux to influx observed in vegetated treatments, reflecting the balance between daytime net photosynthetic uptake and nighttime respiratory losses. The observed diel asymmetry, with daytime CO2 influx and nighttime efflux, closely reflects the interaction between canopy cover and incoming solar radiation. Because VAI integrates relative projected leaf area with light availability, it effectively captures the canopy’s potential for net photosynthesis. The strong predictive role of VAI in the Random Forest model is consistent with well-established light–response functions, where photosynthetic uptake increases with irradiance until saturation and is constrained by leaf area index [59]. In our system, the pronounced daytime influx in the IP treatment demonstrates efficient conversion of intercepted radiation into assimilation, whereas the delayed shift to influx in IPF reflects impaired canopy function under fertilizer stress. Thus, diel CO2 fluxes in semi-arid lettuce soils can be explained mechanistically by the balance between radiation-driven canopy photosynthesis during the day and temperature-modulated respiration at night.

Soil temperature and moisture further modulated CO2 fluxes, with efflux increasing between 29–35 °C and under intermediate WFPS (30–60%), conditions known to enhance heterotrophic respiration [60,61,62,63]. These baseline drivers were modified substantially once vegetation was introduced, as greater leaf area enhanced photosynthetic CO2 uptake and reduced net efflux, particularly in the non-fertilized IP treatment.

The slower and weaker transition to CO2 influx in the fertilized IPF treatment compared to IP indicates that NH4NO3 application may have imposed physiological stress on plants. Reduced relative projected leaf area and thus VAI, as well as high soil NH4+ levels after fertilizer application in IPF plants, support this interpretation, suggesting ammonium toxicity effects. Excessive NH4+ can disrupt ion homeostasis and photosynthetic efficiency, impair nutrient uptake, inhibit root, and thereafter shoot growth [64,65,66,67]. This stress response likely curtailed the plants’ ability to photosynthesize effectively, thereby limiting their capacity to act as a carbon sink and slowing the shift from efflux to influx compared to the non-fertilized IP treatment. These findings emphasize the role of excessive NH4NO3 in impairing plant photosynthetic efficiency, leading to a complex interplay of processes modulating net CO2 exchange in fertilized systems.

4.2. CH4 Dynamics

The CH4 flux dynamics observed in this study reveal a complex interplay of soil and environmental factors with both fertilizer application and plant presence. The RF model identified Tsoil, DAF, VAI, and WFPS as key drivers of CH4 fluxes (Figure 4b). Although CH4 influx appeared to respond to high WFPS values according to the ICE plots (Figure S5(b.4)), these high WFPS levels coincided with fertilizer application in the IPF treatment (Figure 2b), suggesting that the observed correlation between WFPS and CH4 flux may not indicate a causal relationship. This illustrates a broader challenge when interpreting ICE plots from RF models in systems with moderately correlated predictors or short-lived emission pulses, where collinearity and class imbalance may influence how driver importance is represented [68].

Before fertilizer application and lettuce planting, all treatments showed net CH4 influx, indicating that the soil acted as a net CH4 sink (Figure 5a,b). This observation highlights the dominance of soil CH4 oxidation (methanotrophy) over CH4 production (methanogenesis), since methanotrophs thrive in well-drained and aerated soils, whereas methanogens are favored under anaerobic conditions [69]. However, previous studies showed that aerobic upland cultivated soils are not considered the most active CH4 sinks (<0.1 mg CH4 m–2 h–1 [70]), and this is in accordance with the results presented in the current study.

Fertilizer application on day 14 triggered a short-lived within-day peak in CH4 influx in the IPF treatment, suggesting a temporary increase in CH4 uptake. This contrasts with the widely reported inhibitory effects of nitrogen on CH4 uptake [71,72]. However, both increases and decreases in soil CH4 uptake following nitrogen addition have been documented, with several studies reporting a unimodal response where low to moderate nitrogen availability can transiently enhance CH4 uptake before inhibition occurs at higher concentrations [73,74,75]. Our observation may reflect such short-term stimulation, potentially mediated by changes in substrate availability, microbial activity, or interactions with other factors, such as soil moisture. Nevertheless, the transient nature of the response, the short experimental duration, and the collinearity between fertilization and WFPS changes limit our ability to fully disentangle these drivers. Similar transient enhancements have been reported in upland soils, and recent syntheses confirm that nitrogen effects on CH4 uptake are context-dependent, shaped by methanotroph communities, soil aeration, and substrate availability, with responses varying across ecosystems and nitrogen status [71,76]. Further work integrating microbial data would be required to clarify the mechanisms underlying this response.

After lettuce planting, there was a gradual decline in CH4 influx, and towards the end, a shift to net efflux in plant-containing treatments, particularly in the IP treatment (Figure 5a,b). This shift resulted in significantly lower CH4 uptake in the IP treatment compared to the IPF and I treatments, highlighting the differential impact of plant presence and fertilizer application on CH4 fluxes (Table 1). The reduction in CH4 influx over time in the IP treatment may reflect a decline of methanotrophic activity or local changes in soil conditions that favor CH4 production over consumption. Interestingly, VAI showed a positive relationship with CH4 efflux, suggesting that increased plant growth and activity could enhance conditions that favor CH4 emissions (Figure S5(b.2)). Several mechanisms proposed in the literature could explain this pattern, including root exudates providing organic carbon substrates, localized rhizosphere hypoxia reducing O2 availability, and plant-mediated CH4 transport from the soil to the atmosphere (chimney effect) [23,77,78,79,80]. Species with larger root systems or higher transpiration rates may amplify these effects [23,79]. Even though our experiment did not directly measure root zone O2 levels or plant-mediated CH4 transport, the observed temporal trends are consistent with these mechanistic hypotheses. Further research combining high-frequency flux measurements with targeted microbial and plant physiological analyses is needed to quantify the relative contributions of these mechanisms in semi-arid agroecosystems.

4.3. N2O and NH3 Dynamics

In contrast to the complex flux dynamics observed for CO2 and CH4, the effluxes of N2O and NH3 in the current study were predominantly episodic and tightly coupled to fertilizer application (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The RF model identified DAF as a key driver of N2O and NH3 fluxes, with VAI contributing minimally (Figure 4c,d). Although ICE plots for VAI showed some fluctuation, the weak and temporally restricted signal suggests no direct causal relationship (Figure S5(c.2,d.2)). This is further supported by the relatively high correlation coefficient observed between DAF and VAI (Figure S6), reflecting the onset of plant presence and growth immediately following fertilizer application. Both gases exhibited similar emission trajectories: a sharp increase immediately after fertilizer application, followed by a gradual decline. Although the nitrogen released into the atmosphere was ten-fold greater for NH3 than for N2O, the NH3 efflux declined rapidly, ceasing after 6 days, while the N2O efflux persisted for 11 days. As Cameron and colleagues [5] describe, higher soil NH4+ concentrations (Figure S3a) result in greater potential NH3 emissions. NH3 volatilization is further enhanced under alkaline soil conditions (pH > 7; Figure S3c) and becomes more temperature sensitive at higher pH values [5,81,82,83]. The observed NH3 emission pulse and its strong diurnal pattern match earlier reports [5,81], reflecting the interactive effects of NH4+ concentration, soil pH, and temperature in regulating NH3 volatilization.

Although soil NH4+ concentration, soil pH, and mean diel Tsoil remained stable for several days after fertilizer application, NH3 emissions ceased within six days. This decline may reflect the effects of irrigation [84,85], high soil moisture [82], and reduced soil NH4+ availability, for example, due to adsorption onto cation exchange sites [84,85] or uptake by plant roots [5], and NH3 absorption by leaves [5,28,86,87]. In this study, the reduction in NH3 efflux did not coincide with a decline in soil NH4+ but rather with a gradual increase in CO2 influx, particularly in the IPF treatment, suggesting enhanced stomatal CO2 uptake. However, the observed increase in VAI was not associated with changes in NH3 flux. Further research is necessary to delineate the dynamics of NH3 flux in vegetated soils and the factors governing the interactions with plants and soil properties.

NH4NO3 application significantly increases N2O emissions by providing both NH4+ and NO3−, the primary substrates for nitrification and denitrification. Under aerobic conditions, nitrification leads to N2O production as a byproduct, particularly when oxygen availability fluctuates, limiting the complete oxidation of NH4+ [88,89]. In anaerobic microsites, denitrification reduces NO3− to N2O, with emissions persisting when oxygen diffusion is restricted, preventing full reduction to N2 [90,91]. The extended persistence of N2O emissions likely reflects dynamic shifts in soil moisture [92,93], microbial activity [94,95,96], and possible pH effects following fertilization [97,98,99,100]. Consistent with prior studies, the N2O emission factor (0.1%) in this semi-arid system is well below the IPCC Tier 1 default value of 1% [12,13,14,16,100,101]. In agricultural soils with low organic carbon and limited soil moisture, nitrogen cycling processes are strongly dependent on exogenous inputs, and emissions typically spike after fertilizer and irrigation events [100,101].

4.4. High-Frequency Flux Measurements

According to Maier and co-workers [38], the temporal resolution of measurements must account for the anticipated temporal variability of fluxes. A notable strength of our study is the use of high-frequency (16 measurements every 24 h [9]) flux measurements, which allowed us to capture transient and short-lived GHG and NH3 flux events that would likely be missed by traditional low-frequency sampling (e.g., daily or weekly measurements). Indeed, our data demonstrate that flux events in semi-arid cultivated soils occurred on timescales of hours rather than days or weeks. For instance, the sharp pulses of N2O and NH3 emissions (Figure 6 and Figure 7) rose and declined within less than 48 h, while the transient stimulation of CH4 uptake after NH4NO3 application reduced within a single day (Figure 5). Also, these dynamics indicate that conventional manual, low-frequency static chamber campaigns would have missed the majority of such events. Our results align with previous reports from other ecosystems showing that episodic fluxes disproportionately drive cumulative budgets when captured at high temporal resolution [17,18,19].

Moreover, high-frequency measurements also enhanced the temporal precision of diel CO2 and CH4 flux dynamics, revealing subtle treatment-dependent differences in net flux patterns, such as the shift from CH4 influx to efflux and from CO2 efflux to influx in the IP treatment. Random Forest analysis applied to instantaneous measurements, considering within-day patterns of potential explanatory variables (VAI, Tsoil, WFPS, and DAF), quantified the relative importance of these drivers and allowed a mechanistic interpretation of plant–fertilizer–soil interactions. Finally, high-frequency monitoring reduced the uncertainty in cumulative flux estimates, particularly for episodic events, improving confidence in the emission factors derived for both N2O (0.10%) and NH3 (0.97%). This demonstrates that high-frequency sampling is critical for accurately capturing the timing, magnitude, and variability of GHG and reactive nitrogen fluxes in semi-arid agroecosystems.

4.5. Integrated Role of Plant Function and Fertilizer Management in Regulating GHG and NH3 Emissions

The interaction between plant physiological function and nitrogen fertilization is central to understanding GHG and NH3 flux dynamics in semi-arid agroecosystems. While vegetation enhances CO2 uptake through photosynthesis, plant presence and activity can also modulate CH4, N2O, and NH3 emissions through complex and sometimes counteracting mechanisms. In this study, lettuce presence in the IP treatment resulted in net CO2 removal, highlighting the role of plant photosynthesis in offsetting both autotrophic and heterotrophic soil respiration. However, this beneficial effect was reduced in the fertilized vegetated treatment (IPF), where short-term excessive NH4NO3 application prior to planting delayed CO2 uptake and reduced relative projected leaf area (rPLA), suggesting plant stress. The fertilizer rate—intentionally selected above typical agronomic recommendations for lettuce in order to ensure measurable gaseous responses under high-frequency monitoring [36] may have exceeded the crop’s optimal nitrogen demand. While this experimental design allows mechanistic insights, the results should be interpreted as representing short-term dynamics rather than full-season behavior. Such stress may stem from NH4+ toxicity, which impairs nutrient uptake and photosynthetic capacity [102,103], thereby limiting the plant’s potential as a carbon sink. This outcome also indicates that lower nitrogen inputs, aligned with crop demand, could maintain lettuce productivity while reducing both N2O and NH3 losses.

In addition to CO2 dynamics, plant growth also influenced CH4 fluxes. While CH4 influxes were generally dominant, plant presence in the IP treatment was associated with a reduction in CH4 uptake and, eventually, a transition to net efflux. This suggests that root exudates, O2 consumption in the rhizosphere, or even plant-mediated transport may enhance methanogenic conditions [80,104]. Nevertheless, the magnitude of this shift was relatively small and did not offset the broader carbon uptake benefits provided by vegetation [105].

Fertilizer application had a dual and interlinked role. On one hand, it directly stimulated N2O and NH3 emissions by increasing the availability of NO3− and NH4+, which fuel microbial nitrification and volatilization pathways [101,106]. On the other hand, the same fertilizer application impaired plant performance, indirectly modulating emissions by reducing the uptake of reactive nitrogen. Under normal physiological conditions, plants reduce N2O and NH3 losses through active uptake of NO3− and NH4+, biological nitrification inhibition, or by promoting complete denitrification to N2 [26,107]. Disruption of this regulatory role due to fertilizer-induced plant stress therefore acts as a multiplier of emissions.

The Random Forest analysis further clarified these regulatory patterns by distinguishing plant-driven from management-driven controls. VAI outweighed soil variables in regulating CO2 fluxes, underscoring the dominant role of canopy development and light interception. By contrast, DAF emerged as the strongest predictor of both N2O and NH3 emissions, demonstrating the primacy of nitrogen input pulses over plant-related variables. CH4 fluxes showed a mixed control, with soil temperature and VAI both contributing, pointing to interactive effects between rhizosphere activity and environmental conditions. While the short duration of our dataset and moderate collinearity among predictors preclude strict causal inference, the RF analysis is valuable as a hypothesis-generating tool. It highlights how high-frequency flux monitoring, combined with machine-learning approaches, can disentangle the relative importance of plant function versus fertilizer management and direct future work toward targeted microbial and physiological measurements.

These findings reinforce the importance of context-specific nitrogen management strategies, which are extremely important for the design of subsidy schemes for preventing N-pollution. In semi-arid systems, where background emissions are relatively low, the type, amount, and timing of fertilizer strongly influence both direct emissions and plant-mediated regulation of gas fluxes [12,16,84]. Optimized fertilization—aligned with plant developmental stages and physiological needs—can reduce unnecessary nitrogen losses without compromising crop productivity [108,109,110,111]. While our experiment covers only short-term responses, the insights gained can inform Mediterranean and EU climate-smart agriculture policies by supporting practices to minimize GHG and reactive nitrogen emissions while maintaining productivity.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that both vegetation and nitrogen management shape GHG and NH3 flux dynamics in irrigated semi-arid agroecosystems. Vegetated soils act as net CO2 sinks; however, excessive or poorly timed NH4NO3 inputs can impair plant function delaying CO2 uptake and promoting N2O and NH3 losses. While all treatments functioned as CH4 sinks overall, plant presence reduced this capacity, with transient shifts to CH4 efflux in unfertilized vegetated soils. Short-lived CH4 and NH3 flux pulses following fertilization highlight important mechanistic questions, including the transient enhancement of CH4 uptake and the role of plant traits (e.g., root exudation, stomatal conductance, or NH4+ uptake) in modulating nitrogen emissions. These findings have direct implications for climate-smart agriculture policies in Cyprus and other Mediterranean countries. Practical recommendations include inter-allia the application of moderate NH4NO3 rates aligned with crop demand to sustain plant health while minimizing reactive nitrogen losses and ensuring that fertilizer is applied during active growth under favorable soil conditions to mitigate short-term N2O and NH3 flux pulses. At the policy level, integrating plant health, nutrient demand, and environmental conditions within management frameworks can support climate-smart strategies that reduce trade-offs between carbon sequestration and reactive nitrogen emissions in semi-arid cropping systems.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first high-frequency, multi-gas flux dataset from a semi-arid horticultural soil system in the Mediterranean. The novelty lies in demonstrating the sub-daily timing and magnitude of flux pulses that shape net GHG and NH3 balances. By capturing these rapid dynamics, our study shows how plant–fertilizer interactions alter emission trajectories in ways that would remain unresolved with conventional low-frequency approaches. This highlights the value of high-frequency monitoring for improving emission factor estimates and for informing Mediterranean- and EU-level MRV frameworks.

Future research should combine long-term, high-frequency flux monitoring with molecular and physiological analyses to unravel species-specific plant-microbe-soil feedback under varying fertilization regimes. Leveraging both temporal resolution and machine-learning approaches will improve the accuracy of cumulative flux estimates and enhance predictive models, guiding sustainable low-emission management strategies for semi-arid agroecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11111287/s1, Supplementary File S1: Random Forest Analysis [57,112,113,114,115,116,117], Supplementary File S2: Figure S1. Residual scatterplots of the pairwise treatment differences in daily soil temperature and soil water filled pore space vs. time. Figure S2. Relative projected leaf area vs. time scatterplot with fitted ordinary least squares regression models and scatterplots summarizing the effect of treatment each day. Figure S3. Soil NH4-N, NO3-N, and pH vs. time boxplots. Figure S4. Residual scatterplots of the pairwise treatment differences in diel CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 fluxes. Figure S5. ICE plots of predicted CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 fluxes in response to each predictor variable used in the corresponding Random Forest model. Figure S6. Correlation matrix (Kendall’s tau) plot for target (CO2, CH4, N2O, and NH3 instantaneous fluxes) and predictor variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O., A.M.S. and G.T.; methodology, A.M.S., G.T., K.P., M.P. and M.O.; formal analysis, G.T. and A.M.S.; investigation, A.M.S., K.P. and M.P.; resources, M.O.; data curation, A.M.S., G.T. and K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.S. and G.T.; writing—review and editing, A.M.S., G.T., M.O. and K.P.; visualization, A.M.S. and G.T.; supervision, M.O.; project administration, M.O.; funding acquisition, M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Cyprus through the project ‘Reduction and Monitoring of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Cyprus Agriculture’ (C2.1I8).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Explanation | Units |

| A | Chamber Surface Area | m2 |

| a-NSS | Automated Non-Steady-State Soil Chambers | - |

| AR6 | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report | - |

| C | Gas Concentration | ppm |

| CO2e | Carbon Dioxide Equivalent | - |

| DAF | Days After N Fertilization | days |

| F | Raw Flux Rate | ppm m s−1 |

| FC | Corrected Flux Rate | μmol m−2 s−1 |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas(es) | - |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential | g CO2e m−2 |

| NEE | Net Ecosystem Exchange | g CO2 m−2 |

| P | Chamber Pressure | Pa |

| R | Ideal Gas Constant | m3 Pa K−1 mol−1 |

| Rsolar | Solar Radiation | MJ m−2 s−1 |

| RF | Random Forest | - |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error | - |

| sd | Sample standard deviation | - |

| rPLA | Relative Projected Plant Leaf Area | % |

| SCAM | Shape Constrained Additive Model | - |

| T | Chamber Air Temperature | K |

| Tsoil | Soil Temperature | °C |

| t | time | s |

| V | Total System Volume | m3 |

| VAI | Vegetation Activity Index | Rsolar% |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor | - |

| W | Water of the Initial Gas Sample Drawn from the Chamber. | mol% |

| WFPS | Water Filled Pore Space | % |

References

- FAO Emissions Due to Agriculture. Global, Regional and Country Trends 200-2018. In FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Nabuurs, G.-J.; Mrabet, R.; Abu Hatab, A.; Bustamante, M.; Clark, H.; Havlik, P.; House, J.; Mbow, C.; Ninan, K.N.; Popp, A.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU). In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P., Skea, J., Slade, R., Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 747–860. ISBN 9781009157926. [Google Scholar]

- Myhre, G.; Shindell, D.; Bréon, F.; Collins, W.; Fuglestvedt, J.; Huang, J.; Koch, D.; Lamarque, J.; Lee, D.; Mendoza, B.; et al. Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, W.F.; Wiedmann, T.; Pongratz, J.; Andrew, R.; Crippa, M.; Olivier, J.G.J.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Mattioli, G.; Al Khourdajie, A.; House, J.; et al. A Review of Trends and Drivers of Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector from 1990 to 2018. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 073005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.C.; Di, H.J.; Moir, J.L. Nitrogen Losses from the Soil/Plant System: A Review. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013, 162, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, C.A. Paris Agreement. Int. Leg. Mater. 2016, 55, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A. Changing Views of Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agricultural Soil: Key Controlling Processes and Assessment at Different Spatial Scales. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Shakoor, S.; Rehman, A.; Ashraf, F.; Abdullah, M.; Shahzad, S.M.; Farooq, T.H.; Ashraf, M.; Manzoor, M.A.; Altaf, M.M.; et al. Effect of Animal Manure, Crop Type, Climate Zone, and Soil Attributes on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agricultural Soils—A Global Meta-Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themistokleous, G.; Savvides, A.M.; Philippou, K.; Ioannides, I.M.; Omirou, M. A High-Frequency Greenhouse Gas Flux Analysis Tool: Insights from Automated Non-Steady-State Transparent Soil Chambers. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellassen, V.; Stephan, N.; Afriat, M.; Alberola, E.; Barker, A.; Chang, J.-P.; Chiquet, C.; Cochran, I.; Deheza, M.; Dimopoulos, C.; et al. Monitoring, Reporting and Verifying Emissions in the Climate Economy. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F.; et al. Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omirou, M.; Anastopoulos, I.; Fasoula, D.A.; Ioannides, I.M. The Effect of Chemical and Organic N Inputs on N2O Emission from Rain-Fed Crops in Eastern Mediterranean. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, L.; Kiese, R.; Gatter, D.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Buck, R.; Hinz, C.; Murphy, D. V Nitrous Oxide Emissions from a Cropped Soil in a Semi-Arid Climate. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, L.; Murphy, D.V.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Soil Nitrous Oxide and Methane Fluxes Are Low from a Bioenergy Crop (Canola) Grown in a Semi-Arid Climate. GCB Bioenergy 2010, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, G.; Aguilera, E.; Vallejo, A.; Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; Cantero-Martínez, C.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Barton, L.; Volpi, I.; Ibáñez, M.Á. Contribution of the Postharvest Period to Soil N2O Emissions from Arable Mediterranean Crops. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 469, 143186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, M.L.; Aguilera, E.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Adams, D.C.; Abalos, D.; Barton, L.; Ryals, R.; Silver, W.L.; Alfaro, M.A.; Pappa, V.A.; et al. Direct Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Mediterranean Climate Cropping Systems: Emission Factors Based on a Meta-Analysis of Available Measurement Data. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 238, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alice Courtois, E.; Stahl, C.; Burban, B.; Van Den Berge, J.; Berveiller, D.; Bréchet, L.; Larned Soong, J.; Arriga, N.; Peñuelas, J.; August Janssens, I. Automatic High-Frequency Measurements of Full Soil Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in a Tropical Forest. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, J.; Poyatos, R.; Vargas, R. Automated Measurements of Greenhouse Gases Fluxes from Tree Stems and Soils: Magnitudes, Patterns and Drivers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenderfer, H.L.; Cullinan, V.I.; Borde, A.B.; Gunn, C.M.; Thom, R.M. High-Frequency Greenhouse Gas Flux Measurement System Detects Winter Storm Surge Effects on Salt Marsh. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 5961–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitz, F.; Gerdel, K.; Hammerle, A.; Laterza, T.; Spielmann, F.M.; Wohlfahrt, G. In Situ Soil COS Exchange of a Temperate Mountain Grassland under Simulated Drought. Oecologia 2017, 183, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonman, J.; Buzacott, A.J.V.; van den Berg, M.; van Huissteden, C.; van der Velde, Y. Transparent Automated CO2 Flux Chambers Reveal Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Net Carbon Fluxes from Managed Peatlands. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 164, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Wu, J. Gross Photosynthesis Explains the ‘Artificial Bias’ of Methane Fluxes by Static Chamber (Opaque versus Transparent) at the Hummocks in a Boreal Peatland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Korrensalo, A.; Laiho, R.; Kohl, L.; Lohila, A.; Pihlatie, M.; Li, X.; Laine, A.M.; Anttila, J.; Putkinen, A.; et al. Plant-Mediated CH4 Exchange in Wetlands: A Review of Mechanisms and Measurement Methods with Implications for Modelling. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Janzen, H.H.; Nakonechny, E.M.; Cho, C.M. Nitrous Oxide Emission through Plants. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1998, 62, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, A.; Bizimana, F.; Pandey, B.; Yadav, R.K.P.; Dong, W.; Hu, C. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Paddies: Understanding the Role of Rice Plants. Plants 2020, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timilsina, A.; Neupane, P.; Yao, J.; Raseduzzaman, M.; Bizimana, F.; Pandey, B.; Feyissa, A.; Li, X.; Dong, W.; Yadav, R.K.P.; et al. Plants Mitigate Ecosystem Nitrous Oxide Emissions Primarily through Reductions in Soil Nitrate Content: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.A.; Jarvis, S.C. Development of a Novel Method to Measure NH3 Fluxes from Grass Swards in a Controlled Laboratory Environment (a Mini-Tunnel System). Plant Soil 2001, 228, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Leith, I.D.; Raven, J.A.; Fowler, D.; Sutton, M.A.; Nemitz, E.; Cape, J.N.; Sheppard, L.J.; Smith, R.I. Concentration-Dependent NH3 Deposition Processes for Moorland Plant Species with and without Stomata. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 8980–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Gabrielli, P. Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in Agriculture: A Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversa, G.; Elia, A. Growth, Critical N Concentration and Crop N Demand in Butterhead and Crisphead Lettuce Grown under Mediterranean Conditions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartzas, G.; Zaharaki, D.; Komnitsas, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Open Field and Greenhouse Cultivation of Lettuce and Barley. Inf. Process. Agric. 2015, 2, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, M.C.; Soteriou, G.A.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. The Occurrence of Nitrate and Nitrite in Mediterranean Fresh Salad Vegetables and Its Modulation by Preharvest Practices and Postharvest Conditions. Food Chem. 2019, 285, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianquinto, G.; Muñoz, P.; Pardossi, A.; Ramazzotti, S.; Savvas, D. Soil Fertility and Plant Nutrition. In Good Agricultural Practices for Greenhouse Vegetable Crops—Principles for Mediterranean Climate Areas; Baudoin, W., Nono-Womdim, R., Lutaladio, N., Hodder, A., Castilla, N., Leonardi, C., De Pascale, S., Qaryouti, M., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 205–269. ISBN 9789251076491. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlangu, R.I.S.; Maboko, M.M.; Sivakumar, D.; Soundy, P.; Jifon, J. Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Growth, Yield and Quality Response to Nitrogen Fertilization in a Non-Circulating Hydroponic System. J. Plant Nutr. 2016, 39, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohura, P.; Kołota, E. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilization on the Yield and Quality of Field-Grown Leaf Lettuce for Spring Harvest. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 2009, 71, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, I.; Millar, N.; Robertson, G.P. Global Metaanalysis of the Nonlinear Response of Soil Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Emissions to Fertilizer Nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9199–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camera, C.; Zomeni, Z.; Noller, J.S.; Zissimos, A.M.; Christoforou, I.C.; Bruggeman, A. A High Resolution Map of Soil Types and Physical Properties for Cyprus: A Digital Soil Mapping Optimization. Geoderma 2017, 285, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.; Weber, T.K.D.; Fiedler, J.; Fuß, R.; Glatzel, S.; Huth, V.; Jordan, S.; Jurasinski, G.; Kutzbach, L.; Schäfer, K.; et al. Introduction of a Guideline for Measurements of Greenhouse Gas Fluxes from Soils Using Non-Steady-State Chambers. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2022, 185, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Kleineidam, K.; Bakken, L.; Berendt, J.; Bracken, C.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Cai, Z.; Chang, S.X.; Clough, T.; Dawar, K.; et al. Methodology for Measuring Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agricultural Soils Using Non-Isotopic Techniques. In Measuring Emission of Agricultural Greenhouse Gases and Developing Mitigation Options Using Nuclear and Related Techniques; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 11–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easa, S.M. Area of Irregular Region with Unequal Intervals. J. Surv. Eng. 1988, 114, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klein, C.A.M.; Alfaro, M.A.; Giltrap, D.; Topp, C.F.E.; Simon, P.L.; Noble, A.D.L.; van der Weerden, T.J. Global Research Alliance N2O Chamber Methodology Guidelines: Statistical Considerations, Emission Factor Calculation, and Data Reporting. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.; Storelvmo, T.; Armour, K.; Collins, W.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Frame, D.; Lunt, D.J.; Mauritsen, T.M.; Palmer, M.D.; Watanabe, M.; et al. The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks and Climate Sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 923–1054. ISBN 9781009157889. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvides, A.M.; Fotopoulos, V. Two Inexpensive and Non-Destructive Techniques to Correct for Smaller-Than-Gasket Leaf Area in Gas Exchange Measurements. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvides, A.M.; Velez-Ramirez, A.I.; Fotopoulos, V. Challenging the Water Stress Index Concept: Thermographic Assessment of Arabidopsis Transpiration. Physiol. Plant 2022, 174, e13762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, D.R.; Nelson, D.W. Nitrogen—Inorganic Forms. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 643–698. ISBN 9780891189770. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, D.G.; Kalra, Y.P.; Crumbaugh, J.A. Nitrate and Exchangeable Ammonium Nitrogen. In Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis; SSSA Book Series; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. ISBN 9780891188667. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer Method Improved for Making Particle Size Analyses of Soils. Agron. J. 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics; Hillel, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2003; ISBN 978-0-12-348655-4. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Wilcox, R.R. Introduction to Robust Estimation and Hypothesis Testing, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 9780128047330. [Google Scholar]

- Mundo, A.I.; Tipton, J.R.; Muldoon, T.J. Generalized Additive Models to Analyze Nonlinear Trends in Biomedical Longitudinal Data Using R: Beyond Repeated Measures ANOVA and Linear Mixed Models. Stat. Med. 2022, 41, 4266–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix, version 0.95; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Gómez, S.; Guenni, O.; Bravo de Guenni, L. Growth, Leaf Photosynthesis and Canopy Light Use Efficiency under Differing Irradiance and Soil N Supplies in the Forage Grass Brachiaria decumbens Stapf. Grass Forage Sci. 2013, 68, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, K.; Davidson, E.A.; Tang, J. Diel Patterns of Autotrophic and Heterotrophic Respiration among Phenological Stages. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, J.; Fóti, S.; Papp, M.; Pintér, K.; Nagy, Z. Separating the Effects of Temperature and Carbon Allocation on the Diel Pattern of Soil Respiration in the Different Phenological Stages in Dry Grasslands. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.A. Response of Microbial Communities to Water Stress in Irrigated and Drought-Prone Tallgrass Prairie Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 2750–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widanagamage, N.; Santos, E.; Rice, C.W.; Patrignani, A. Study of Soil Heterotrophic Respiration as a Function of Soil Moisture under Different Land Covers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 200, 109593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, K.S.; Craine, J.M.; Fierer, N. Nitrogen Fertilization Inhibits Soil Microbial Respiration Regardless of the Form of Nitrogen Applied. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2336–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. NH4+ Toxicity in Higher Plants: A Critical Review. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 159, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.M.; Ajwa, H.A.; Smith, R. Nitrite and Ammonium Toxicity on Lettuce Grown under Hydroponics. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2007, 39, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilpha, J.; Song, J.; Jeong, B.R. Ammonium Phytotoxicity and Tolerance: An Insight into Ammonium Nutrition to Improve Crop Productivity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Tian, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, S. A Novel Random Forest Integrated Model for Imbalanced Data Classification Problem. Knowl. Based Syst. 2022, 250, 109050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yao, Z.; Brüggemann, N.; Shen, Z.Y.; Wolf, B.; Dannenmann, M.; Zheng, X.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Effects of Soil Moisture and Temperature on CO2 and CH4 Soil–Atmosphere Exchange of Various Land Use/Cover Types in a Semi-Arid Grassland in Inner Mongolia, China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mer, J.; Roger, P. Production, Oxidation, Emission and Consumption of Methane by Soils: A Review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2001, 37, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cheng, X.; Xing, W.; Liu, G. Soil-Atmosphere Exchange of CH4 in Response to Nitrogen Addition in Diverse Upland and Wetland Ecosystems: A Meta-Analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 164, 108467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Feng, M.; Cui, Y.; Liu, G. The Impacts of Nitrogen Addition on Upland Soil Methane Uptake: A Global Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]