1. Introduction

“An apple a day keeps the doctor away”, as the old English saying goes. Apples are healthy and nutritious, but in many European countries, the level of apple consumption is falling (Fedrigotti and Fischer [

1]). The same is happening in Norway.

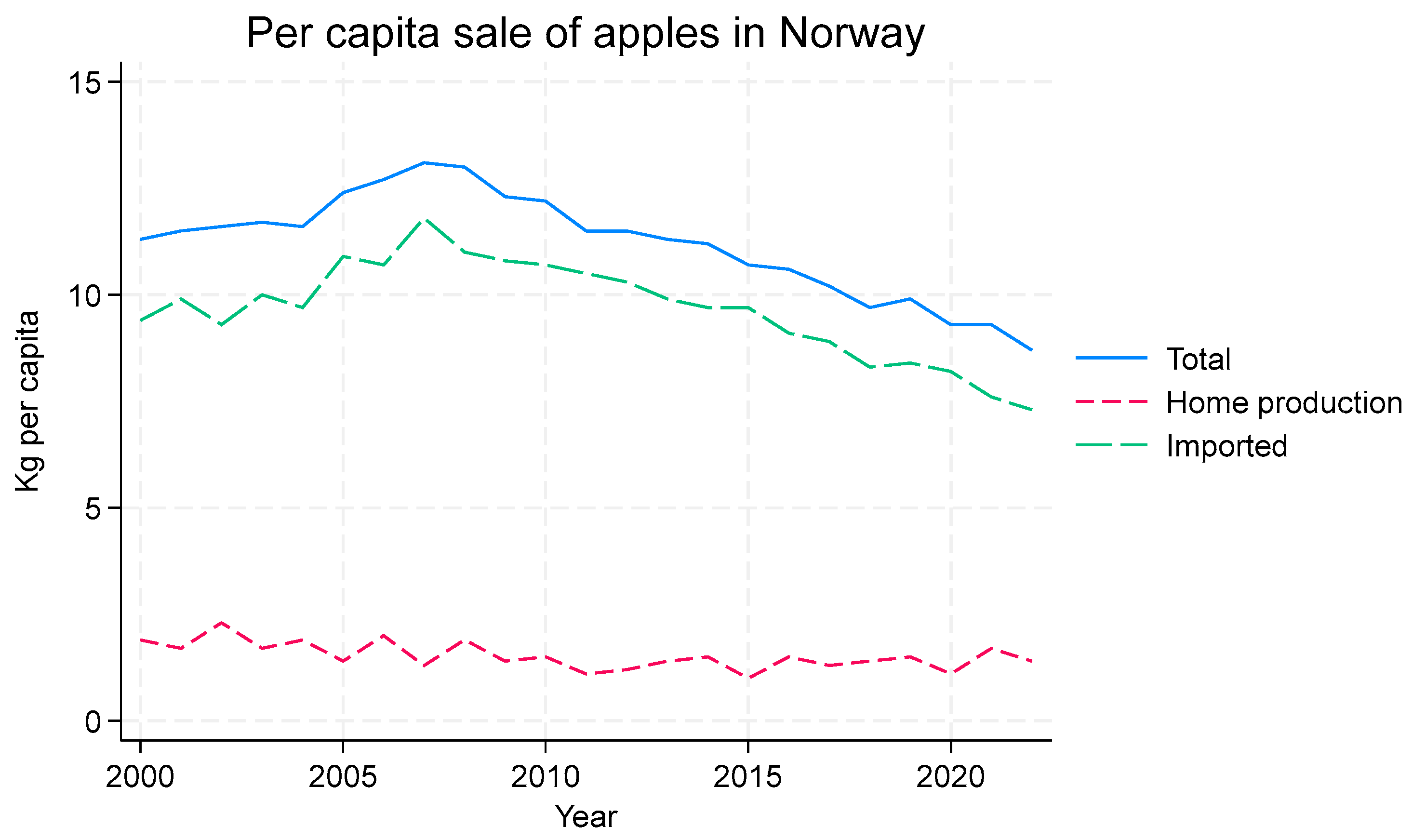

Figure 1 shows that the per capita sales of apples in Norway increased from 11.3 kg per capita in 2000 to 13.1 in 2007, but fell in the following years. In 2022, the quantity of apple sales was 8.7 kg per capita. Sales of imported apples fell proportional to the total sale, while sales of home-grown apples varied between 1 and 2 kg per capita during the whole period.

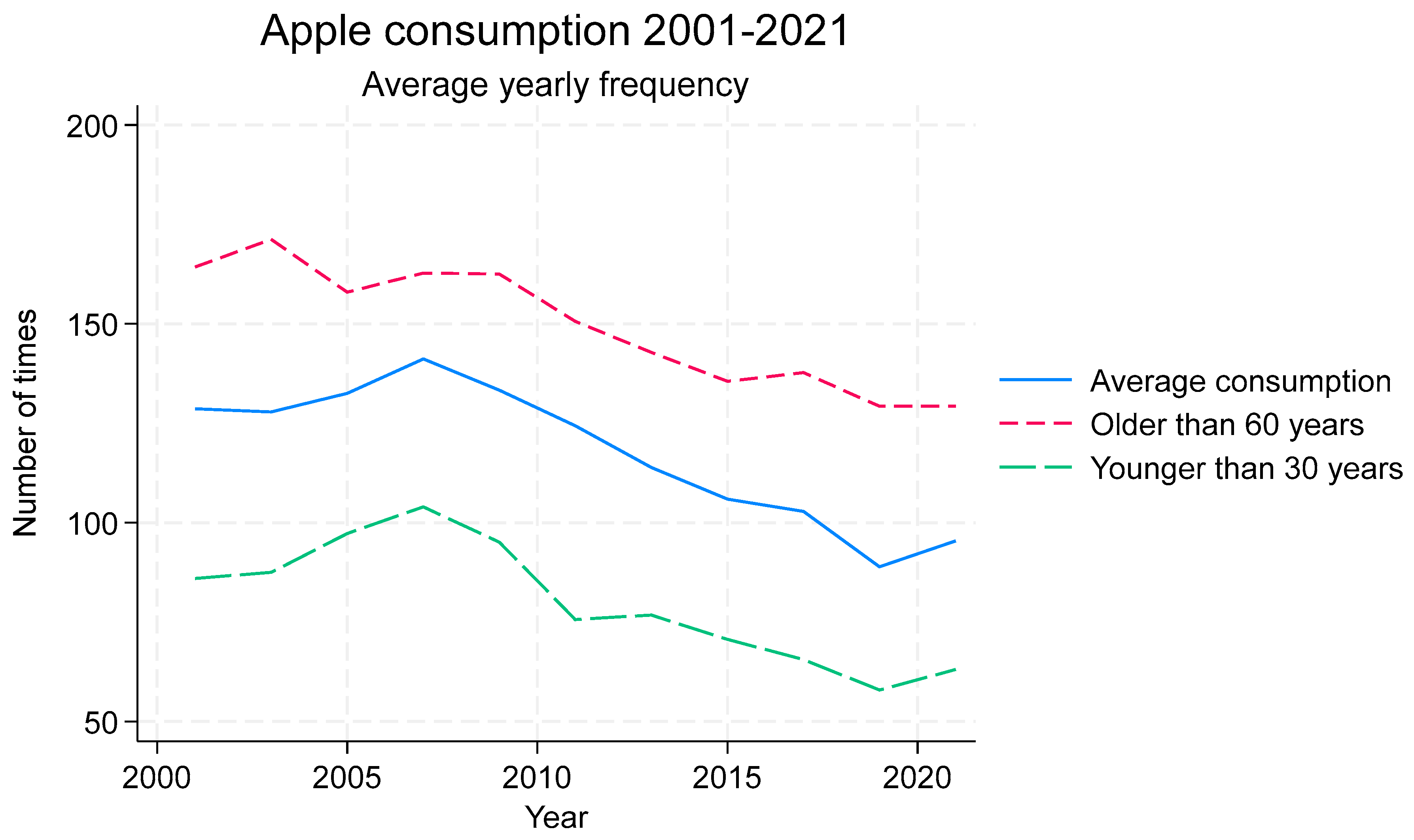

Figure 2 shows the same picture as

Figure 1. The frequency of apple consumption has fallen throughout the whole population, for older individuals (above 60 years) and younger individuals (below 30 years). A decrease in apple consumption has potential negative impacts on public health, given that the level of fruit and vegetable consumption in most countries is far lower than recommended by health authorities [

2]. Furthermore, apples are produced with a low carbon footprint [

3], and they are generally even more environmentally friendly when they are consumed in the country where they are produced, as this reduces the need for long-distance transport with corresponding greenhouse gas emissions and the risk of food loss [

4].

The apple sector in Norway, together with the farmers’ unions and agricultural authorities, has set an aim to increase the consumption and production of Norwegian fruit and vegetables by 50% by 2035 [

5]. In 2023, only 17% of the fresh apples consumed in Norway were domestically produced [

6], and this low figure is, to a large extent, due to the short season of Norwegian apples and a lack of investment in storage facilities. There is, however, a large potential to increase apple production in the country, and lately a large amount of new apple tree fields have been planted, which will increase the apple supply over the coming years [

7].

However, the falling consumer demand for apples is a challenge for the sector. According to a study by Fedrigotti and Fischer [

1], there are several possible explanations for the declining apple consumption experienced in many countries, including the increasing average age of consumers, higher apple prices, consumer dissatisfaction with the available apple varieties, and higher healthy nutrient levels in other fruits.

In Norway, due to the prevalence of generally small-scale production units and high labor costs, Norwegian apple producers face fierce competition with lower-priced imported apples. Strategies to overcome these challenges are being implemented: new apple varieties have been introduced to cater for consumers’ preferences [

8], and new storage facilities have been built to extend the season for selling Norwegian apples beyond the period with import protection from tariffs [

9]. The tariff on imported apples is NOK 4.83 per kilo in the period from May 1 to November 30; in this period, you can find Norwegian apples in the supermarket [

7]

Given the challenge of low-apple-consumption levels, there is need for research that sheds light on consumer preferences and apples’ attractiveness in general, and for Norwegian apples in particular. Consumers with different attitudes or demographic backgrounds have different tastes and preferences for apple varieties’ qualities [

1,

10,

11], and these may also differ between different countries [

12]. It is important to improve our understanding of these preferences to better be able to provide for each ones’ needs. The marketing of products is increasingly performed through social media, targeting different societal groups with different messages [

13]. It is therefore important to know what affects the preferences for apples for different groups in order to create an efficient marketing strategy for apples.

In this paper, we will look at the motivations for consuming apples. Our point of departure is Bazzani et al. [

14] who performed a study about food values in Norway and the US. Their study was based on a best–worst scaling approach. They found that the safety of food had the highest ranked value in Norway. This was followed by naturalness (that the food is made without modern food technologies like genetic engineering, hormone treatment, or food irradiation), taste, animal welfare, and nutrition. Factors like environmental impact or appearance had a low value.

Performing an online experiment might be expensive and time-consuming and require funding. When survey questions already exist, we suggest using a random effect ordered logistic regression model to range the food values among individuals and in different groups of individuals. This is a handy way to analyze and range the apple values. The advantage of reusing data has been described by many researchers (for example Pasquetto et al. [

15]), and it is highly recommended by public organizations (for example, the European Commission [

16]).

In this study, we use questions from a consumer survey, where many of the questions are similar to those in Bazzani et al.’s study, create a random effect ordered logistic model, and use the model to rank the factors of apple consumption by importance.

This is conducted to answer the following two research questions:

What are the most important values for people when they buy apples?

How do people with different demographic backgrounds and levels of trust rank these values?

In

Section 1, the data from the survey are presented. Then, the methods are described. The graded response model is used to construct a latent variable for trust in the apple producers and the food authority, and the ranking of the apple values is based on the random effect ordered logistic regression model. Following this, the results from the estimation are presented, and the predicted probabilities for the average apple consumer and different subgroups are shown. The results are discussed, and finally a conclusion is drawn.

2. Food Values and Fruits and Vegetables

Food values are meta preferences connected to food that may explain what is important when individuals purchase food. Lusk and Briggeman (2009) [

17] constructed 11 food specific values that may contribute to explaining why individuals purchase some food products, but not others. These values are naturalness (the extent to which the food is produced with modern technologies), taste, price, safety, convenience, nutrition, tradition, origin, fairness (that all the parts involved in the production of food equally benefit), appearance, and environmental impact. Lusk and Briggeman performed an online best–worst experiment in the US and used a mixed effect logistic regression model to range the values. Bazzani et al. (2018) [

14] used the same techniques as did Lusk and Briggeman, but they included novelty (the food is something new that you have not tried before) and animal welfare and excluded tradition. Linking food values to consumption of fruits and vegetables has been conducted in different ways. Best–worst experiments have been conducted with modified questions to find and range the values for fruits and vegetables [

18,

19], olive oil [

20], fresh-cut salads [

21], and avocados [

22], and Girgenti et al. [

23] have performed this for raspberries and blueberries.

Other methods have also been used to find food values and link them to the consumption of different fruits and vegetables. Ward et al. [

24] used a database of US individuals in which consumers were asked to rank 14 fruits and vegetable attributes as first, second, or third, while Spina et al. [

25] used a survey where food values were determined using Likert scale questions. Then, clusters were constructed and linked to mango consumption in Italy.

3. Data

A survey was conducted in January 2020 by the market research company Norstat, who operates with internet panels and provide respondent samples that are representative of the general population in terms of gender, age, and geographical distribution. Participants were randomly recruited and were compensated with gift cards or the opportunity to make donations. A description of the method for data collection can also be found in Milford et al. [

26]. One thousand and fifty-two individuals from 18 to 91 years and representative of the Norwegian population participated in the survey.

Table 1 shows the relative frequency of responses to our choice-based question, “How important are the following values to you when you are buying apples?”, in relation to 10 variables. The variables were the taste of the apple, the type of the apple, appearance, i.e., the look of the apple, price, the environmental impact of its production, the safety of eating the apple, if the apple is produced in Norway, or if the apple is produced in a particular region of Norway, if the wrapping contains the number of apples suitable for my consumption, and finally that no pesticides are used in production.

For each value, the individuals responded with one of the following: “Not important”, “Little important”, “Neither nor”, “Somewhat important”, “Very important”, or “Don’t know”. For each individual, their responses were used as the input to the random effect logistic regression model.

4. About Trust

Fruits and vegetables contain a lot of credence attributes. Most consumers do not know how the food is produced, the technology that is used in production, how the products are treated by the farmer, the wholesaler, the retailer, or in transportation. In addition, most of the apples in Norway are imported (see

Figure 1). Hence, trust in the value chain for apples will necessarily have an impact on some of the apple values, food safety in particular, and hereby apple consumption. A review of the literature about trust in the food system was conducted by Wu et al. [

27].

It is common for conventional (not organically certified) apple farmers to apply different types of pesticides to avoid the loss of yield due to various diseases or harmful insects. Applying pesticides requires farmer to abide to a set of regulations regarding which pesticides can be used, how much, how often, and how close to the harvesting time. In Norway, the Norwegian Food Safety Authorities oversee that the regulations are followed and that pesticides are applied safely. Nevertheless, consumers may still be worried about excessive amounts of pesticide being used in cultivation and pesticide residues on apples for sale on supermarket shelves. Believing that the apples are safe to eat and produced in a proper way is a question about trust. People who buy conventional apples have very few possibilities of knowing which types or quantities of pesticides are used in production, or what the effects are on health and the environment. To find out how trust in apple producers and food regulators influence apple values, we included a latent trust variable in our model. The trust variable was constructed by the graded response model [

28] using the eight choice-based questions in

Table 2.

The first two questions are about food authorities, the next five questions are about apple producers, and the last questions is about penalty for food producers not playing by the rule.

Table 2 shows that Norwegian consumers have a large degree of trust in food authorities and apple producers. For example, more than 60 percent think that food authorities do not authorize pesticides harming the environment or human health. Furthermore, more than 60 percent think that apple producers follow the rules for pesticides and that they try to minimize their use.

5. About the Centrality Index

To find out if there are differences concerning the food values between the individuals living in cities or central areas and the individuals living in rural areas, we included a measure of centrality. The centrality index from Statistics Norway [

29] is a code with values for each of the Norwegian counties, giving a measure for the centrality of the county. The value of the index is based on the travel time to workplaces and service functions in each of the 357 counties in Norway. The index has value from 0 (just possible in theory) to 1000 (Oslo) along a continuous scale. Along with the use of Statistics Norway to classify items according to centrality, the index was used by Mittenzwei et al. [

30] to study the rural–urban divide in the perceived effects of climate policy.

6. The Covariates

Table 3 shows the covariates (before standardization) used in the random effect ordered logistic model. The mean age in the survey is 46.9 years old. The value of the centrality index is 846, indicating that the average individual lives in a rather urbanized area. Furthermore, 48 percent of the sample consists of males, 53 percent have a university education, and 43 percent of the households have children below 18 years living at home. The household income per consumer unit is calculated as the gross household income divided by the square root of numbers of persons in the households, as recommended by Sarfati [

31]. The yearly average of this income is NOK 520,000. Trust is an index with a mean 0 and a standard deviation close to 1 by construction.

Everyday apple eaters differ somewhat from the average individual. They are younger on average and more likely to live in central areas, have a higher education level and a higher income, and are less likely to have children.

7. Methods

To construct the latent variables for trust in apple producers and food authorities, we used the graded response model suggested by Samejima [

28]. This model is well suited to construct latent variables out of discrete graded variables by comparing the items (questions) across alternatives and individuals. The latent variable for trust constructed by the 8 questions in

Table 2 is an index where individuals who have high degree of trust will have high value for the trust variable. The model can be defined as individual

j’s probability to choose alternative

k of K possible alternatives for item

i.

is the probability of each individual j answering question i to choose response k.

is a discrimination parameter for question i.

is a cutpoint parameter that identifies the boundaries between order outcomes.

is the latent variable of person j.

To construct our trust variable, we used the data described in

Table 2 with

K = 5 categories,

I = 8 questions, and

J = 1010 individuals.

In our trust questionnaire, j is one of the following alternatives: “I don’t think it is true”, “I think it might not be true”, “Neither nor”, “I think it might be true”, and “I think it is true”. is the latent variable which was estimated for each individual j. This continuous variable has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation close to 1 by construction. The higher the value of is, the higher the trust in food authorities and apple producers.

Equation (2) describes the ordered logistic regression model. Since our outcome variables are graded and categorical, we must use an estimation technique suited to analyze these variables. The ordered logistic regression model is an obvious choice. If

y is a variable indicating the individual’s choice of a category, c is a category,

x is a vector of covariates,

is a vector of parameters,

is the cut point between category

c and category

c + 1, and

C is the total number of categories, then the probability that the outcome is in category

c is

where

H is the cumulative distribution function.

If

yic is an indicator, it takes the value 1 if respondent

i is in category

c, and 0 otherwise. The likelihood function for the ordered logistic regression model is given by

where the

is the cutoff points, and

is a vector of parameters.

In our case, H is the logistic distribution function with the categories “Not important” (c = 1), “Slightly important” (c = 2), “Neither nor” (c = 3), “Somewhat important” (c = 4), and “Very important” (c = 5). “Don’t know” was treated as “Neither Nor” (c = 3).

Since we obtained ten statements, described in

Table 1, with potentially high correlation between the responses, we transformed the data to a panel structure to account for the covariances between the error terms in the ten equations.

The probability of observing outcome

c for statement

k and individual

i is given by

where the indicator variable

if statement

k is the focus, or 0 otherwise, and

vi is individual specific random variation that is assumed

iid ).

8. Results

Our survey consists of 1052 representative Norwegian individuals. Of those, 1010 individuals answered the questions in

Table 1. The procedure was as follows: First, using the data described in

Table 2, we estimated

, the latent variable for trust in the food authorities and in the apple producers. This was conducted with the procedure irt grm in Stata [

32]. Then, each of the continuous variables in

Table 3 were standardized (the mean was withdrawn, and the difference was divided by the standard deviation) to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation equal to one. All the continuous variables were then on the same scale, and the other variables were dummy variables with values 0 or 1. Hence, numerical problems were avoided, and it was possible to compare the estimated coefficients from the ordered logistic regression model. After standardization, all the covariates in

Table 3 were inserted into the model. The command xtologit in Stata was then used to estimate the random effect ordered logistic regression model. This model was also used by Mittenzwei et al. [

30]. The estimated parameters are shown in the

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Table 4 shows that women put more emphasis on the type of apple than men. The same is true for university-educated individuals compared to individuals without university education. When it comes to taste, men put more emphasis on taste than women, and taste is also more important for university-educated individuals than individuals without university education. Furthermore, taste is more important for individuals with children in the household. Appearance is more important when there are children in the household and for individuals with a high degree of trust in the apple producers and authorities. Not surprisingly, low-income individuals put more importance on price than high-income individuals. Older people find the environmentally friendly production of apples more important than younger people; it is also more important for women than men and for individuals with a low degree of trust.

Table 5 shows that safety (that the apple is safe to eat) is more important to individuals living in non-central areas, to men, and to university-educated individuals. Furthermore, it is more important for low-income people than for high-income people and for those in households with children. That the apple is produced in Norway is more important for older people and for women, and it is more important for people living in rural areas and for individuals living in households without children. We see nearly the same pattern for the region (that the apple is produced in a particular region in Norway). Which region the apple is produced in is an important value for individuals of an older age, women, individuals without university education, high-income people, and those in households without children. The importance of wrapping, that the apple wrapping contains a suitable number, is emphasized by people of a younger age, women, and those in households without children. Finally, the effects of pesticides, that no pesticides are used in production, is emphasized by individuals of an older age, women, and individuals with a low degree of trust in apple producers and food authorities.

The estimated parameters in

Table 4 and

Table 5 were inserted in Equation (4) to predict the probabilities of answering “somewhat” or “very” important to the questions in

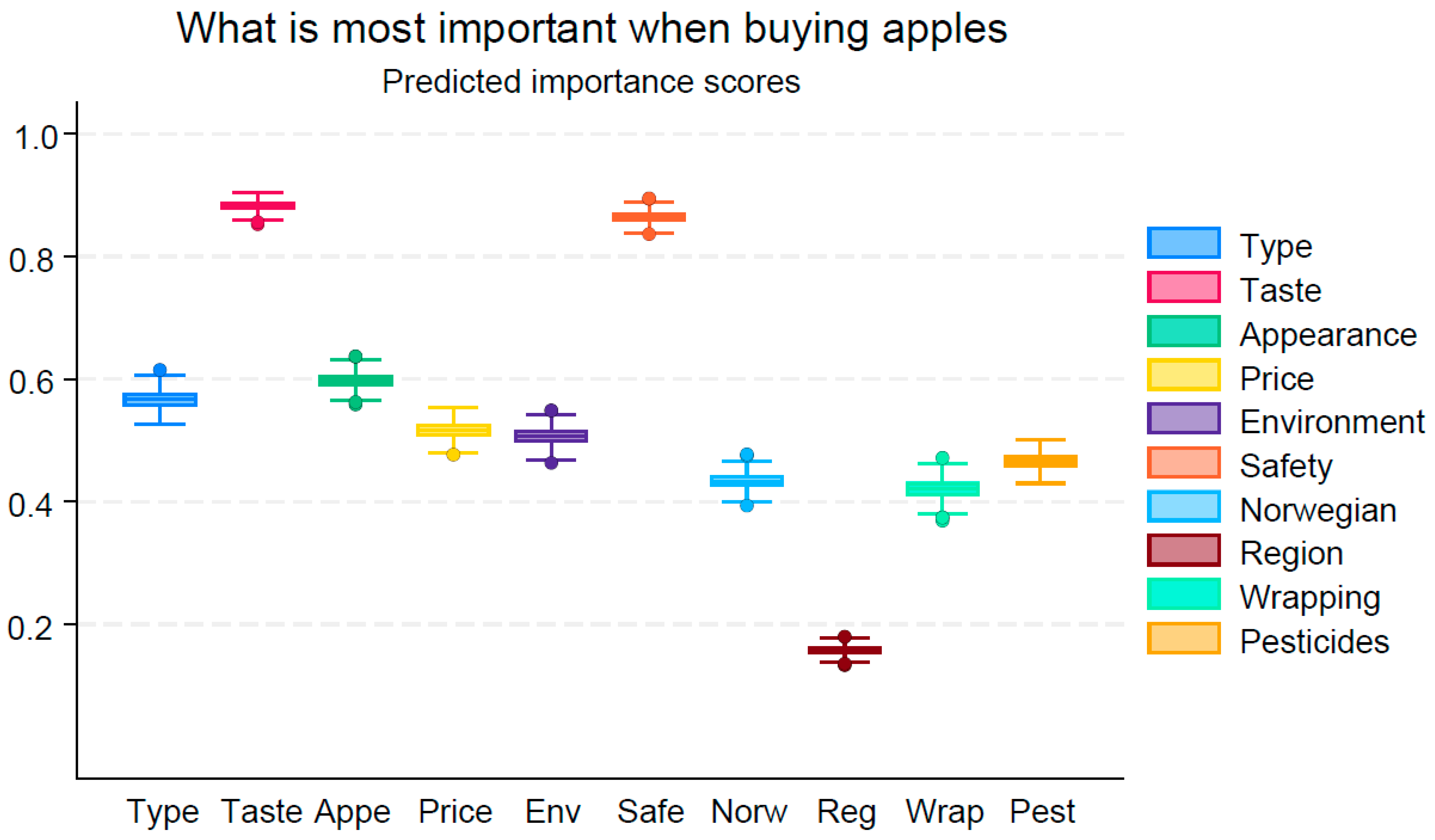

Table 1. This was conducted to produce our importance scale. First, we predicted the probabilities of answering “somewhat” or “very” important to the 10 questions when all the covariates were kept at the mean. For the subgroup “Everyday apple eaters”, the covariates were kept at the mean value of individuals who eat apples every day. After that, we used the model to predict the same probabilities for the rest of the different subgroups, keeping the focus variable at the focus value, and the other variables were held at their mean of the full sample. The subgroup “Old age” was constructed as the variable age was measured at the 90th quantile of the age distribution, and all the other variables were kept at the mean values. The subgroup “Young age” was constructed as age kept at the 10th quantile of the age distribution, and all the other variables were measured at their mean. The 90th and 10th quantiles of age correspond to 72 years and 23 years, respectively. The 90th quantile and the 10th quantile of the centrality variables are living in Oslo and rural areas, respectively. The subgroups “Males” and “Females” were constructed, keeping the dummy variable Male as 1 or 0, respectively, and all the other variables at their mean. The other subgroups were constructed accordingly. The groups “University”/“Not university” and “With children”/“Without children” were kept as the dummy variables at 1 and 0, and all the other variables were kept at their mean. For individuals with high and low incomes, the 90th quantile corresponds to NOK 813,000 and NOK 247,000 per consumer unit, respectively. The importance probabilities for individuals with high and low levels of trust were constructed as the 90th and 10th quantiles of the trust variable, and all the other variables were kept at their mean. This process was performed with 100 bootstrap iterations to construct the means and the standard deviations of the predictions. The predictions of the means of importance scores with 95% confidence intervals are shown in

Figure 3.

Table 6 shows the ranking of consumer importance of individuals when buying apples. Ranking was conducted in the following way: First, for the mean, , the highest importance probability was found. This was taste, so taste was placed as number one. Then, the second-highest importance probability from the same column was found, which was safety, and safety was more than one standard error lower than taste, so safety was placed as number two. Third was appearance, and forth was type. Fifth was price, but price was less than one standard error smaller than environment, so both price and environment were placed as number five, and so on. The value closest to the focus one was picked, if it was less than one standard error away from the focus one, it acquired the same ranking, and if it was more than one standard error away, it assumes one ranking lower.

At the mean and in all the subgroups, taste and safety were ranged as the top two importance factors. The subgroups everyday apple eaters, being younger, living in Oslo, being female, being university educated, having a high income, and living with and without children ranked taste before safety. For the other subgroups, taste and safety were both ranked as number one. For the everyday apple eaters, appearance and type were ranked third. Overall, in the subgroups between 71% and 94% think that taste is important when they buy their apples. Between 72% and 92% think that safety is important. Then, for the mean, the ranking is as follows: the appearance and type of apple were ranked as the third and fourth most important values, while environmental production and price were ranked fifth. The four least important factors are the use of pesticides, if the apple is produced in Norway, if the wrapping is suitable, and if the apple is produced in a particular region in Norway.

9. Discussion

Taste and safety are the apple values that are ranked highest for all the subgroups, which is in line with the other studies [

12,

14,

33]. Appearance is ranked as number three, but it is lower (fifth) for the consumers who are older and those with a low degree of trust. That appearance is less important for older consumers corresponds to the findings of Péneau et al. [

34], and one explanation could be that older consumers have not grown up with the “picture-perfect” apples supplied today. Consumers with a low degree of trust might be aware that pesticides, to a large extent, are used for cosmetic reasons [

35], and this could make them more skeptical to apples with a good appearance.

The relatively high ranking of the type of apple indicates that Norwegian apple eaters have good knowledge about and clear preferences for apple types. This factor is ranked higher for the daily apple eaters, who might be more conscious about their preferences.

The value environment, that the apple is produced in an environmentally acceptable way, is, on average, ranked fifth, and the relatively high importance of this value corroborates with another study of European consumers [

12]. However, environment is ranked lower (eight) for those with a high degree of trust and higher (third) for those with a low degree of trust. The same pattern is found for pesticides, which is ranked lower than the average for people with a high degree of trust (nineth), and higher for people with a low degree of trust (third). Pesticide use is probably the most important reason apple production may cause environmental degradation; hence, the two aspects are closely linked. In addition, people might avoid pesticides for health reasons, which is linked with the value “safety”. It is likely that those who do not trust that the producers and the public authorities take enough responsibility for pesticide use are more inclined to try to avoid food with pesticides. This is in line with findings by Yeh et al. [

11] and Milford et al. [

26], who both found that people with a low degree of trust are more inclined to buy organic apples.

Avoiding pesticides is also more important for individuals who eat apples every day than it is for the average. This makes sense as pesticide residues would potentially be more harmful for daily apple eaters than for individuals who seldomly eat apples. Compared with other food products, apples are products which may have a higher risk of pesticide residues [

36].

It is interesting to note that the environment and pesticides are more important to older than they are to younger consumers; this is not consistent with the previous studies finding that younger people are more environmentally concerned than older people [

37,

38]. This could indicate that apples are a special case that young people may not have much focus on. That females are more concerned with environment and pesticides is consistent with the literature [

38].

Price is ranked as number five for the average consumer, and this average importance corroborates with Fedrigotti and Fischer [

1]. However, it was ranked lower by the everyday apple eaters, which is likely to be because when you eat apples daily, it becomes a habit. And habits are difficult to change even when the price increases. Gustavsen and Rickertsen [

39] found that price changes had a larger impact on fruit consumption levels of households with low consumption of fruits than for households with high fruit consumption. Hence, when fruit prices increase, consumers with low fruit consumption will reduce their fruit consumption by more than the households with high-level fruit consumption. Price is also, unsurprisingly, ranked higher than average for low-income consumers and lower than average for high-income consumers. Furthermore, individuals that are older and living in rural areas rank price lower. That older consumers are less price-sensitive than younger consumers when measured at the same income level is consistent with Hurgobin et al. [

40]. Our results show that rural consumers rate other concerns such as Norwegian origin higher than price.

The value being Norwegian, that the apple is produced in Norway, is, on average, ranked as number eight. This low ranking contrasts the findings of previous studies from various countries [

41], as well as a survey made in Norway in 2021, where 69% of the respondents agreed with the statement “I prefer Norwegian fruit to fruit produced abroad” [

42]. The reason why Norwegian origin, in our study, is ranked lower than the other values could be that people prefer Norwegian apples because they are perceived to have attributes that are already covered and ranked higher, such as taste, safety, type, environmental friendliness, and reduced pesticide use. The preference for domestic food that is linked with these values is supported, for instance, by a recent literature review on the origin labelling of food [

41] and a study on the preference for Norwegian strawberries [

43]. Furthermore, Norwegian apples are generally only available for a few months of the year, which might partially explain the low ranking. The higher ranking of Norwegian apples by individuals living in rural areas is consistent with the existing literature on the preference for domestic food products [

44,

45]. One explanation could be the stronger support for domestic agriculture from this group, who might identify more strongly with, or even be themselves, farmers.

Lastly, we see that wrapping and region are the lowest ranked values. In Norway, most apples are sold loose, which means that people can choose themselves how many apples they want, which is a likely explanation for the low ranking of the value “wrapping”. The low ranking of region is in line with a study by Török et al. [

12], who found that the regional origin of fruits and vegetables was less important to Norwegian people than it was to other European consumers, and this finding could indicate that Norwegian apple-producing regions have been less successful in branding their products than those in other countries. However, this low ranking could also be explained by the same factors as for the value “Norwegian”, which is that the potential preference for apples from a particular region is linked with the aspects already covered by other values such as taste, appearance, and the type of apple. It is also possible that if the question instead had been about locally produced apples, the ranking would have been higher, as shown in the other studies [

41,

46].

10. Potential Limitations of This Study

As in all cross-sectional studies, this one also has its limitations. When a survey company is performing an online survey, they draw a sample of individuals from a panel that is representative of the population focused no with respect to some criteria, for example, age, gender, and the place of living. But the panel is not independent. The panel is recruited via the internet. Hence, the sample will suffer from selection bias [

47].

Another potential limitation of this study is the use of a survey instead of an experiment. In the survey, the participants did not assess the apple values against each other. When considering a few values, as in a best–worst experiment, individuals must make clear distinctions between the values. However, respondents may find it challenging to identify the best and the worst options.

Furthermore, when responding a survey, or participating in an online experiment about choices, the following question can be made: do individuals respond as they would do in real life? Jerolmack and Khan [

48] argue that what people say is often a poor predictor of what they do.

Lastly, the results for the subgroup everyday apple eaters are not directly comparable to the other subgroups. The other subgroups were evaluated at the mean value of the other covariates, except for the variable focused on. The everyday apple eaters, however, were evaluated at the mean values of the subsample everyday apple eaters, which were different from the sample means (see

Table 3). This was conducted to include that subgroup without estimating the model on a subset of the data segmented on an endogenous variable (the frequency of eating apples), which would have created selection bias.

Further research about apple values should use other data samples and other methods to replicate our results. Best–worst experiments can be performed, and values may be retrieved by mixed logit regressions or latent class models. Furthermore, survey data with questions regarding apple values may also be analyzed with other models for ordered categorical variables.

11. Conclusions

The results of this study may also have relevance for other markets and provide some indications regarding factors which may contribute to an increase in the demand for Norwegian apples or other food products if the information is used for, for instance, product development, package design, advertisement campaigns, or in policies relevant to the apple sector. It confirms the results of the previous studies, that taste and safety are important values for all apple consumers, regardless of their sociodemographic background. This means that providing and developing apple varieties with high-level taste qualities needs to be a priority. The high weight given to safety indicates that is it important to avoid risks such as pesticide residues that might damage Norwegian apples’ reputation as safe. The appearance and type of apples are also important apple values. Furthermore, we find that environmentally friendly production is important, and especially for older people and people with a low degree of trust. An emphasis on the environmental benefits of apples could be more important than what is often believed, both in terms of how they are produced, and communication around this aspect, especially for older consumers. A loss of trust in the environmental friendliness of Norwegian apples, for example if it were revealed to have a negative effect on local environments, could cause damage to the sector. This indicates that policies and regulations that ensure environmentally friendly production methods for apples are important.

Price is not rated as highly important, but it is ranked higher for low-income consumers, and increased price is likely to affect general sales and the apple intake of low-income groups. However, as apple prices in Norway over the last ten years have increased substantially compared to food prices in general [

49], the current food policies do not seem to be leading to development in the right direction.

Consumers’ preference for Norwegian apples, as found, for instance, in the Kantar survey [

42], seems to come largely from their reputation as being tasty, safe, and environmentally friendly. Hence, when marketing Norwegian apples, these aspects need to be emphasized, for all sociodemographic groups.