Valorization of Plant Biomass Through the Synthesis of Lignin-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

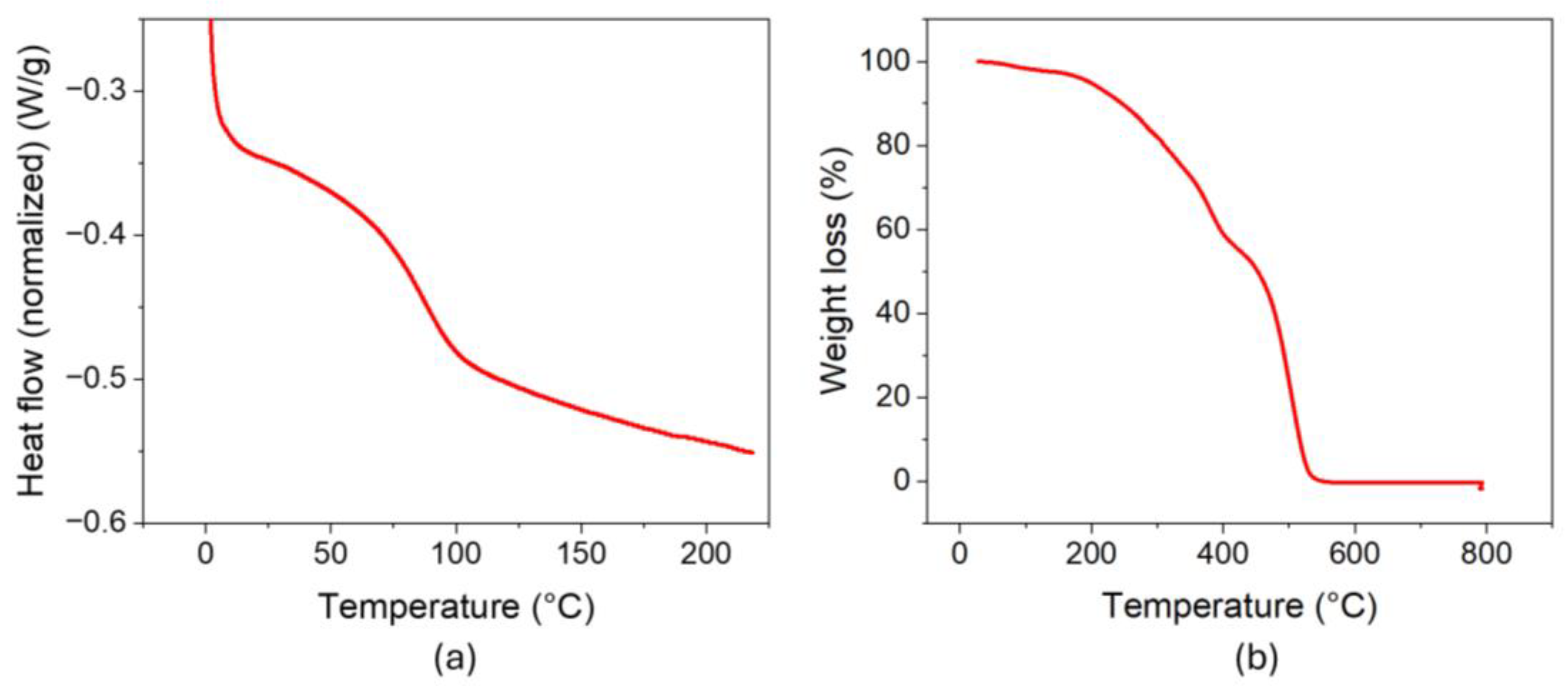

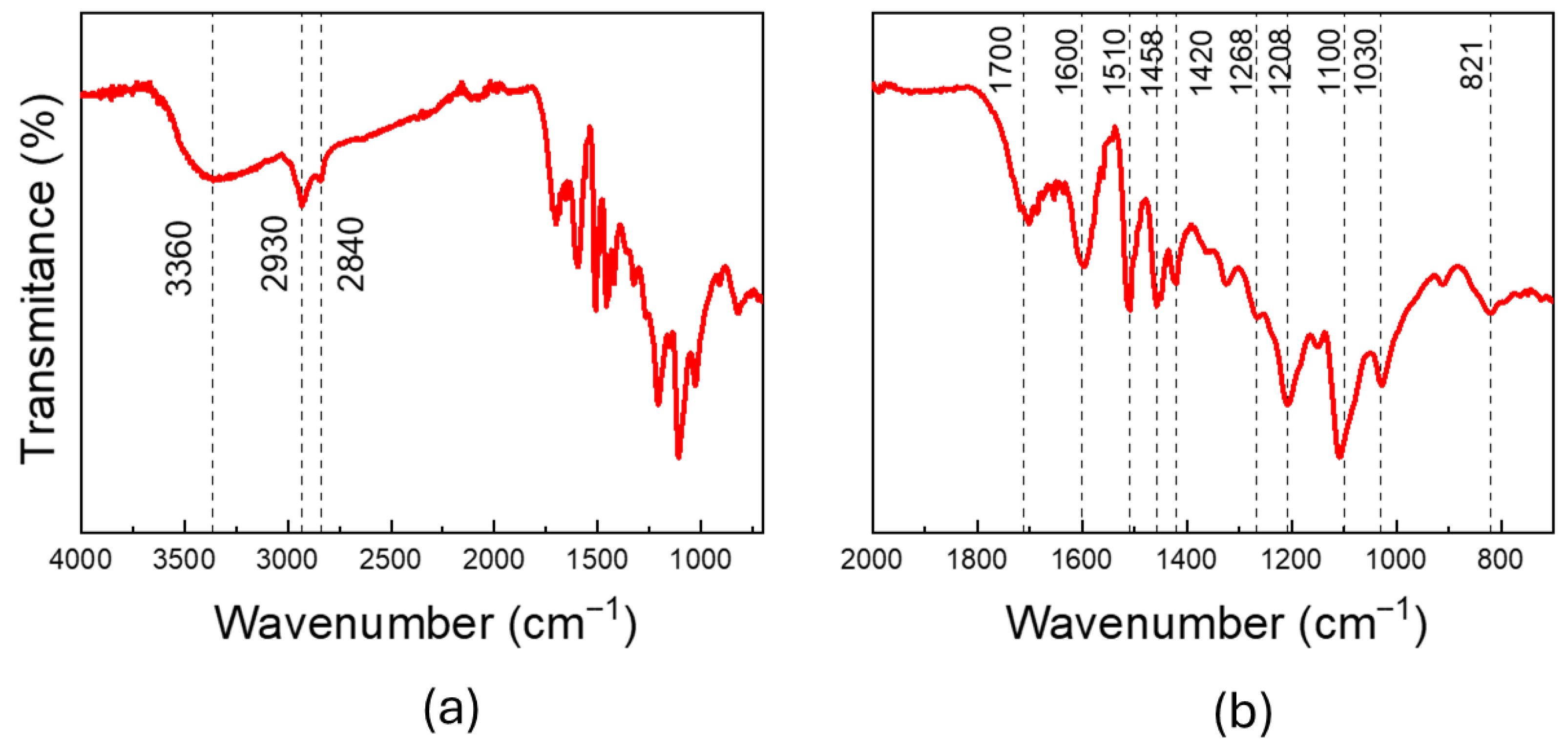

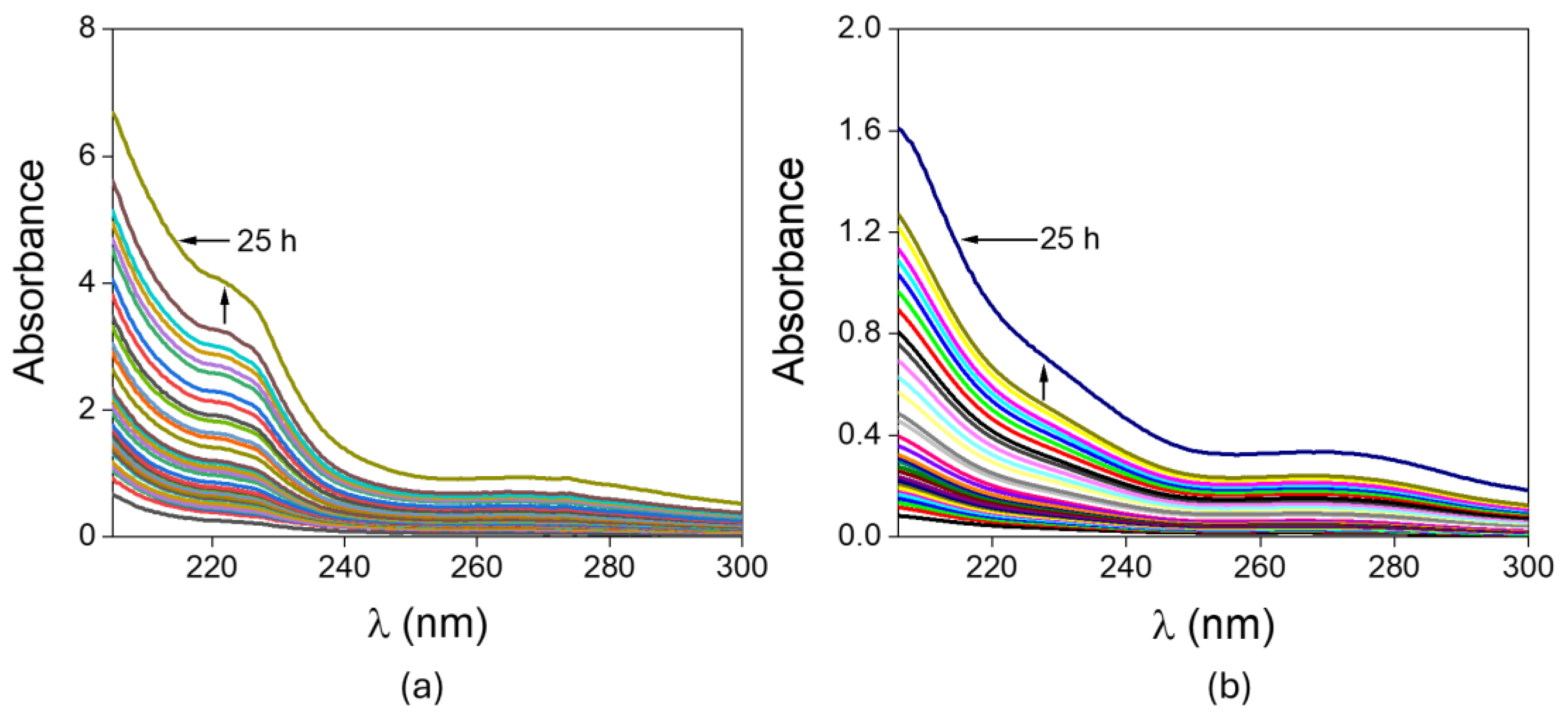

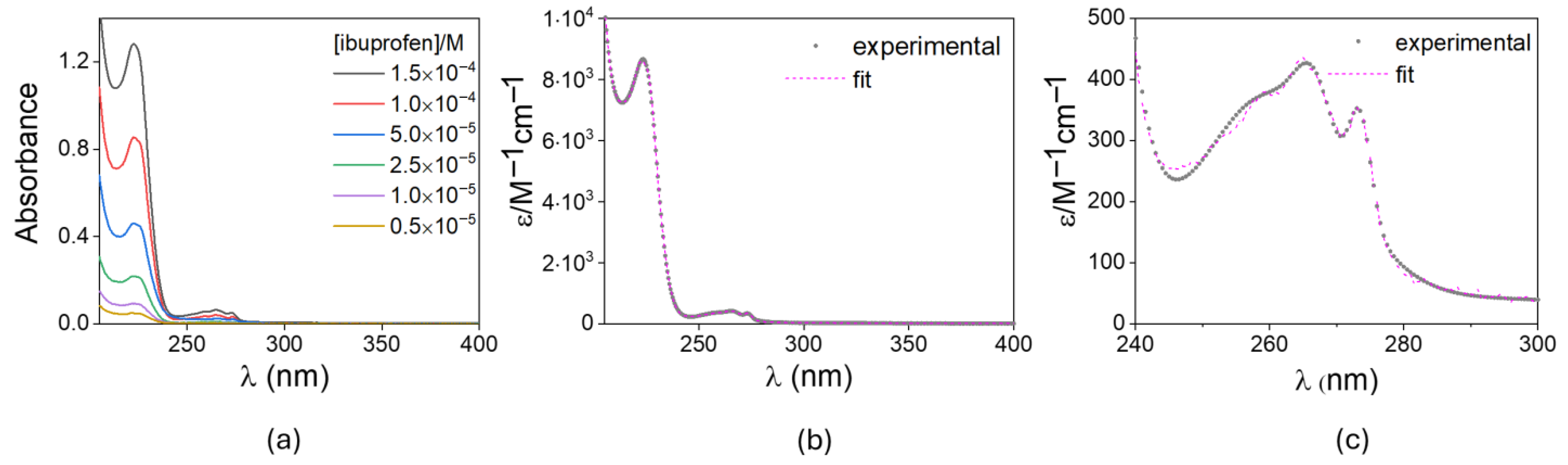

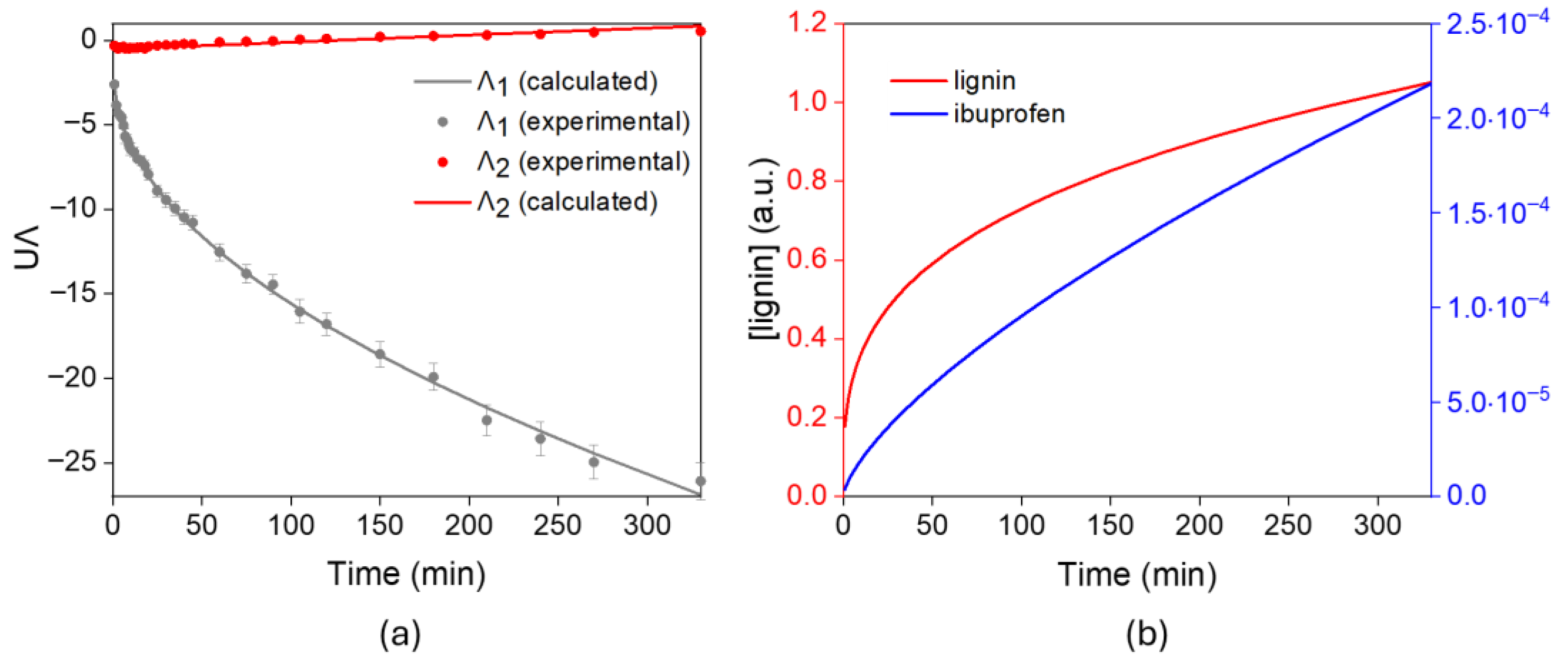

2. Results and Discussion

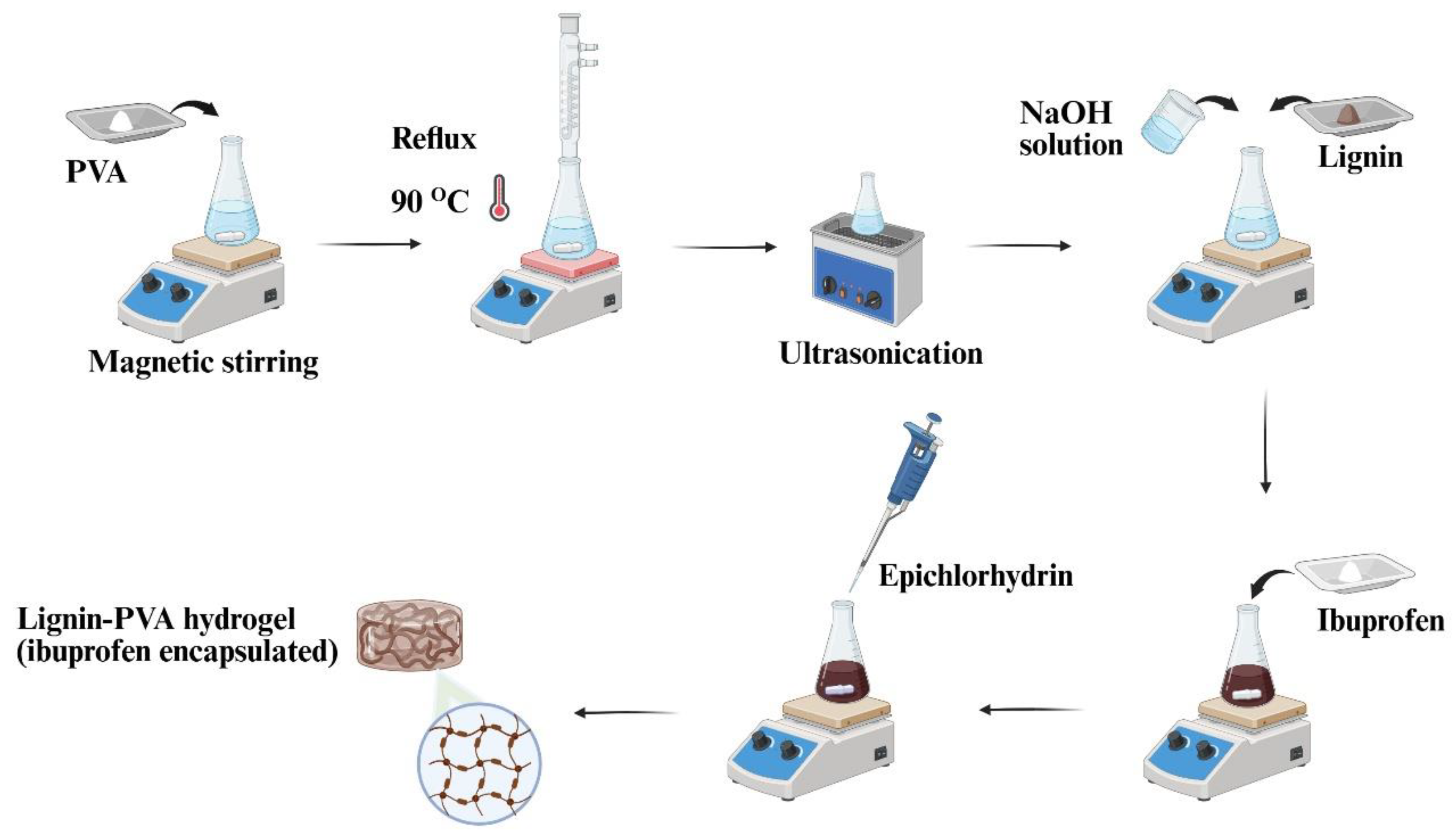

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Lignin Extraction

4.2. Extraction Percentage

4.3. Structural Characterization

4.4. Hydrogel Preparation

4.5. In Vitro Drug Release Study

4.6. Drug Quantification and Spectrophotometric Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| ECH | Epichlorohydrin |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| KP | Korsmeyer–Peppas |

| MCR | Multivariate curve resolution |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PVA | Poly(vinyl alcohol) |

| SVD | Singular value decomposition |

| Tg | Glass transition temperature |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| UV-VIS | Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy |

References

- Möslinger, M.; Ulpiani, G.; Vetters, N. Circular economy and waste management to empower a climate-neutral urban future. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, F.; Ugwuishiwu, B.; Nwakaire, J. Agricultural waste concept, generation, utilization and management. Niger. J. Technol. 2016, 35, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Vargas Garcia, M.; Rodriguez, F.J.A.; Fernandez Guelfo, L.A.; Fernandez Morales, F.J.; García-Morales, J.L.; Ramirez, R.M.; Herrero, R.M.; Casco, J.M.; Suárez, E.F. Residuos Agrícolas I.1. In De Residuo a Recurso: El Camino hacia la Sostenibilidad; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 13–98. [Google Scholar]

- Servicios Medioambientales de Valencia, S.L. La Importancia Del Tratamiento de Residuos Agrícolas. Available online: https://links.uv.es/8qmUZcm (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Ahmad, U.M.; Ji, N.; Li, H.; Wu, Q.; Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Ma, D.; Lu, X. Can lignin be transformed into agrochemicals? recent advances in the agricultural applications of lignin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionova, M.V.; Bozieva, A.M.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Leong, Y.K.; Lan, J.C.-W.; Veziroglu, A.; Veziroglu, T.N.; Tomo, T.; Chang, J.S.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. A comprehensive review on lignocellulosic biomass biorefinery for sustainable biofuel production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 1481–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Fraceto, L.F.; Fazeli, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Savassa, S.M.; de Medeiros, G.A.; do Espírito Santo Pereira, A.; Mancini, S.D.; Lipponen, J.; Vilaplana, F. Lignocellulosic biomass from agricultural waste to the circular economy: A review with focus on biofuels, biocomposites and bioplastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Li, R.; Xu, P.; Li, T.; Deng, R.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Q. the cornerstone of realizing lignin value-addition: Exploiting the native structure and properties of lignin by extraction methods. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 402, 126237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, S.C.; Nakasu, P.Y.S.; Scopel, E.; Araújo, M.F.; Cardoso, L.H.; Costa, A.C. da organosolv pretreatment for biorefineries: Current status, perspectives, and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norfarhana, A.S.; Ilyas, R.A.; Ngadi, N.; Othman, M.H.D.; Misenan, M.S.M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F. Revolutionizing lignocellulosic biomass: A review of harnessing the power of ionic liquids for sustainable utilization and extraction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakar, F.S.; Ragauskas, A.J. Review of current and future softwood kraft lignin process chemistry. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 20, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.; Nuruddin, M.; Hosur, M.; Tcherbi-Narteh, A.; Jeelani, S. Extraction and characterization of lignin from different biomass resources. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2015, 4, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, N.; Muddasar, M.; Nasiri, M.A.; Cantarero, A.; Gómez, C.M.; Muñoz-Espí, R.; Collins, M.N.; Culebras, M. Lignin-Derived ionic hydrogels for thermoelectric energy harvesting. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdocia, X.; Hernández-Ramos, F.; Morales, A.; Izaguirre, N.; de Hoyos-Martínez, P.L.; Labidi, J. Lignin Extraction and Isolation Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Deuss, P.J. The isolation of lignin with native-like structure. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 68, 108230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Sifontes, M.; Domine, M.E. Lignina, estructura y aplicaciones: Métodos de despolimerización para la obtención de derivados aromáticos de interés. Av. Cienc. Ing. 2013, 4, 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, F.G.C.; Soares, A.K.L.; Santaella, S.T.; Silva, L.M.A.E.; Canuto, K.M.; Cáceres, C.A.; de Freitas Rosa, M.; de Andrade Feitosa, J.P.; Leitão, R.C. Optimization of the acetosolv extraction of lignin from sugarcane bagasse for phenolic resin production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 96, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, N.-E.E. Despolimerización de Lignina para su Aprovechamiento en Adhesivos para Producir Tableros de Partículas; Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Tarragona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Shukla, A.; Tiwari, S.; Srivastava, M. A Review on delignification of lignocellulosic biomass for enhancement of ethanol production potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, C.H.; Réthoré, G.; Weiss, P.; Fatimi, A. sustainable biomass lignin-based hydrogels: A review on properties, formulation, and biomedical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, R.; Fardim, P. Lignin-based materials for emerging advanced applications. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 41, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukheja, Y.; Kaur, J.; Pathania, K.; Sah, S.P.; Salunke, D.B.; Sangamwar, A.T.; Pawar, S.V. Recent advances in pharmaceutical and biotechnological applications of lignin-based materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culebras, M.; Barrett, A.; Pishnamazi, M.; Walker, G.M.; Collins, M.N. Wood-derived hydrogels as a platform for drug-release systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.K.; Uddin, T.; Sujan, S.; Tang, Z.; Alemu, D.; Begum, H.A.; Li, J.; Huang, F.; Ni, Y. Preparation of lignin-based hydrogels, their properties and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 245, 125580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadem, E.; Ghafarzadeh, M.; Kharaziha, M.; Sun, F.; Zhang, X. Lignin derivatives-based hydrogels for biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, R.; Fardim, P. Lignin-Based Materials for Biomedical Applications; Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Zúniga, M.G.; Lee, S.K.; Oh, E.; Suhr, J. PH and temperature responsive uv curable lignin-based hydrogels with controllable and outstanding compressive properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 206, 117583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, F.; Muhamad, I.I.; Nazari, Z.; Mobini, P.; Khatir, N.M. Investigation of acyclovir-loaded, acrylamide-based hydrogels for potential use as vaginal ring. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 16, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E.; Arrebola, R.I.; Bascón-Villegas, I.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Domínguez-Robles, J.; Rodríguez, A. Industrial application of orange tree nanocellulose as papermaking reinforcement agent. Cellulose 2020, 27, 10781–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Alén, R.; Paleologou, M.; Kannangara, M.; Kihlman, J. Lignin recovery from spent alkaline pulping liquors using acidification, membrane separation, and related processing steps: A review. BioResources 2019, 14, 2300–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, F.S.; Jemaat, Z.; Khan, M.R.; Yunus, R.M.; Beg, M.D.H. Isolation and characterization of soda lignin from opefb and evaluation of its performance as wood adhesive. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 107, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaucamp, A.; Muddasar, M.; Amiinu, I.S.; Leite, M.M.; Culebras, M.; Latha, K.; Gutiérrez, M.C.; Rodriguez-Padron, D.; del Monte, F.; Kennedy, T.; et al. Lignin for energy applications—State of the art, life cycle, technoeconomic analysis and future trends. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 8193–8226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Toledano, A.; Andrés, M.Á.; Labidi, J. Study of the antioxidant capacity of miscanthus sinensis lignins. Process. Biochem. 2010, 45, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, K.A.; Belmont, S.R.; Enguita, J.M.; Sheehan, J.D. Polar aprotic solvent properties influence pulp characteristics and delignification kinetics of co2/organic base organosolv pretreatments of lignocellulosic biomass. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 288, 119808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, E.I.; Adeosun, S.O. Sustainable Lignin for Carbon Fibers: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, R.; Aspée, N.; Negrete-Vergara, C.; Venegas-Yazigi, D.; Gutiérrez-Cutiño, M.; Moya, S.A.; Zúñiga, C.; Cantero-López, P.; Luengo, J.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Solvent effects on the molecular structure of isolated lignins of eucalyptus nitens wood and oxidative depolymerization to phenolic chemicals. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 201, 109973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alriols, M.G.; Tejado, A.; Blanco, M.; Mondragon, I.; Labidi, J. Agricultural palm oil tree residues as raw material for cellulose, lignin and hemicelluloses production by ethylene glycol pulping process. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 148, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Sun, J.X.; Sun, R.; Fowler, P.; Baird, M.S. Comparative study of organosolv lignins from wheat straw. Ind. Crops Prod. 2006, 23, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Iram, F.; Atif, M.; Fatimah, N.E. Functionalization of arabinoxylan in chitosan based blends by periodate oxidation for drug release study. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.R.; Derry, S.; Straube, S.; Ireson-Paine, J.; Wiffen, P.J. Faster, higher, stronger? evidence for formulation and efficacy for ibuprofen in acute pain. Pain 2014, 155, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrgie, A.T.; Darge, H.F.; Mekonnen, T.W.; Birhan, Y.S.; Hanurry, E.Y.; Chou, H.Y.; Wang, C.F.; Tsai, H.C.; Yang, J.M.; Chang, Y.H. Ibuprofen-loaded heparin modified thermosensitive hydrogel for inhibiting excessive inflammation and promoting wound healing. Polymers 2020, 12, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-García, D.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Pérez-Alvarez, L.; Hernández-Olmos, S.L.; Guerrero-Ramírez, G.L.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L. Lignin-based hydrogels: Synthesis and applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavioun, P.; Doherty, W.O.S. Chemical and thermal properties of fractionated bagasse soda lignin. Ind Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Gómez, C.M.; Muñoz-Espí, R.; Cantarero, A.; Collins, M.N.; Culebras, M. Amine-functionalized lignin hydrogels for high-performance n-type ionic thermoelectric materials. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 8283–8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

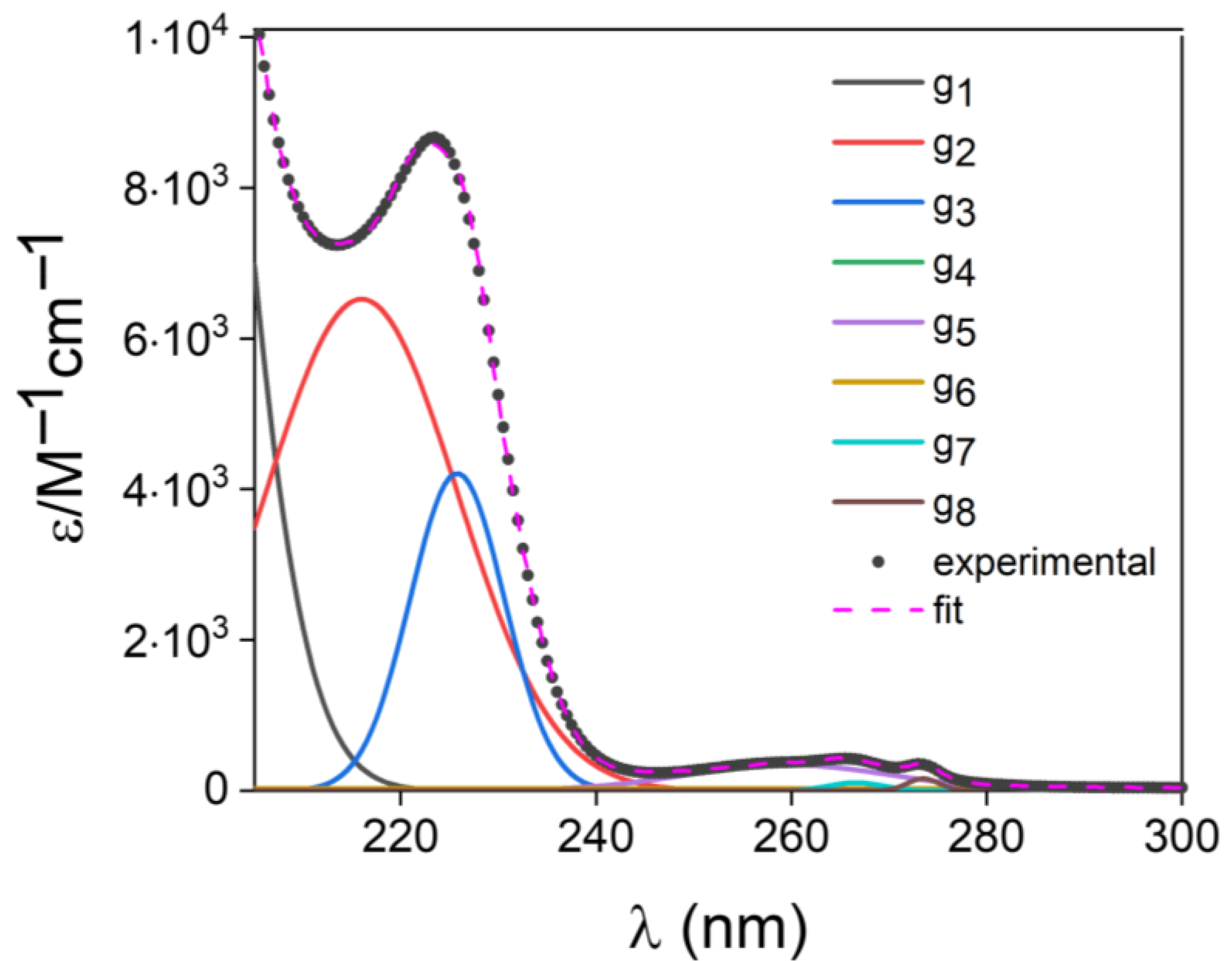

| i | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.129253 × 106 | 1.934617 × 102 | 7.721564 |

| 2 | 6.521756 × 103 | 2.159834 × 102 | 9.816513 |

| 3 | 4.210365 × 103 | 2.257779 × 102 | 4.814559 |

| 4 | 1.583795 × 102 | 2.905355 × 102 | 2.165994 × 101 |

| 5 | 3.418569 × 102 | 2.596958 × 102 | 1.056078 × 101 |

| 6 | 2.577380 × 101 | 2.650000 × 102 | 1.651721 × 102 |

| 7 | 1.072217 × 101 | 2.665899 × 102 | 2.747695 |

| 8 | 1.614182 × 101 | 2.735039 × 102 | 1.632219 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cárdenas-Vargas, N.; Jabeen, N.; Huerta-Recasens, J.; Pérez-Pla, F.; Gómez, C.M.; Collins, M.N.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Muñoz-Espí, R.; Culebras, M. Valorization of Plant Biomass Through the Synthesis of Lignin-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery. Gels 2026, 12, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020104

Cárdenas-Vargas N, Jabeen N, Huerta-Recasens J, Pérez-Pla F, Gómez CM, Collins MN, Ruiz-Rubio L, Muñoz-Espí R, Culebras M. Valorization of Plant Biomass Through the Synthesis of Lignin-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery. Gels. 2026; 12(2):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020104

Chicago/Turabian StyleCárdenas-Vargas, Natalia, Nazish Jabeen, Jose Huerta-Recasens, Francisco Pérez-Pla, Clara M. Gómez, Maurice N. Collins, Leire Ruiz-Rubio, Rafael Muñoz-Espí, and Mario Culebras. 2026. "Valorization of Plant Biomass Through the Synthesis of Lignin-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery" Gels 12, no. 2: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020104

APA StyleCárdenas-Vargas, N., Jabeen, N., Huerta-Recasens, J., Pérez-Pla, F., Gómez, C. M., Collins, M. N., Ruiz-Rubio, L., Muñoz-Espí, R., & Culebras, M. (2026). Valorization of Plant Biomass Through the Synthesis of Lignin-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery. Gels, 12(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020104