Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer as a Key Scaffold for Bone Regeneration: Synergistic Effects with Photobiomodulation and Membrane Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Histomorphometric Analysis

2.2. Collagen Fiber Birefringence Analysis

2.3. Histomorphometric and Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. 14 Days

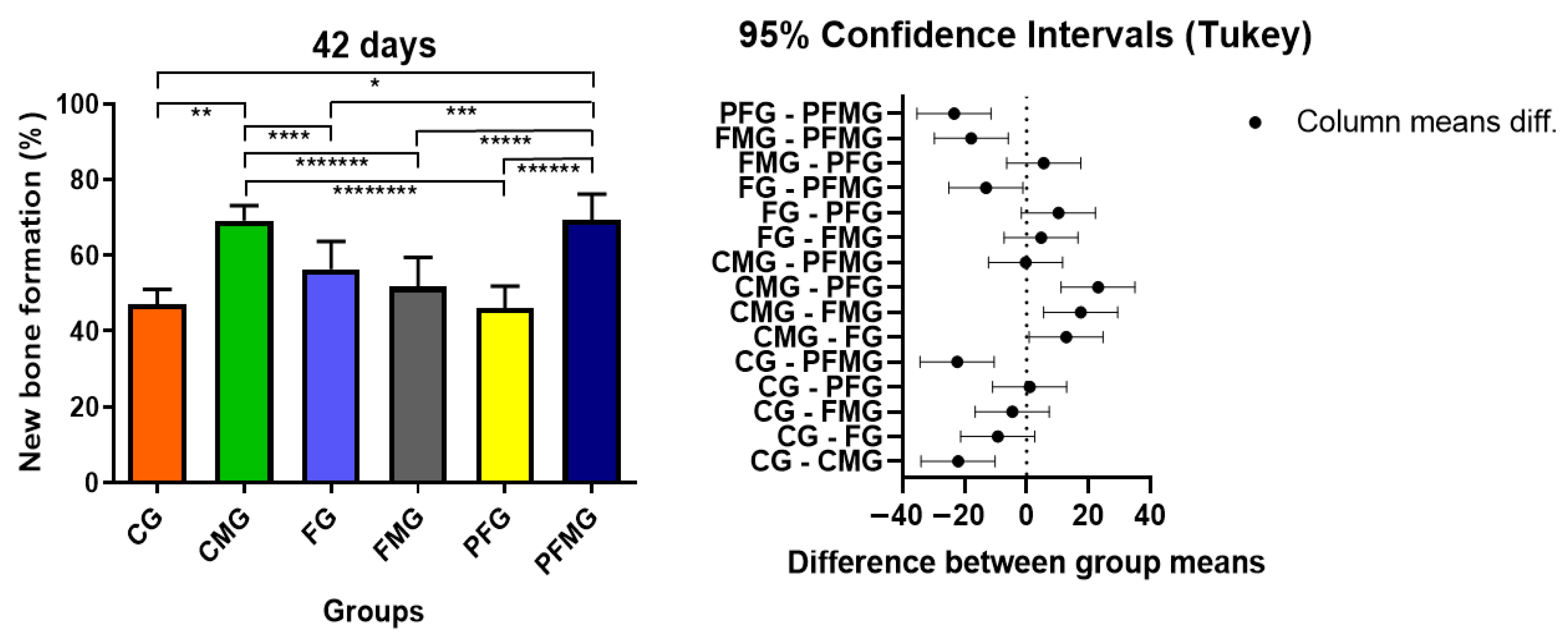

2.3.2. 42 Days

3. Conclusions

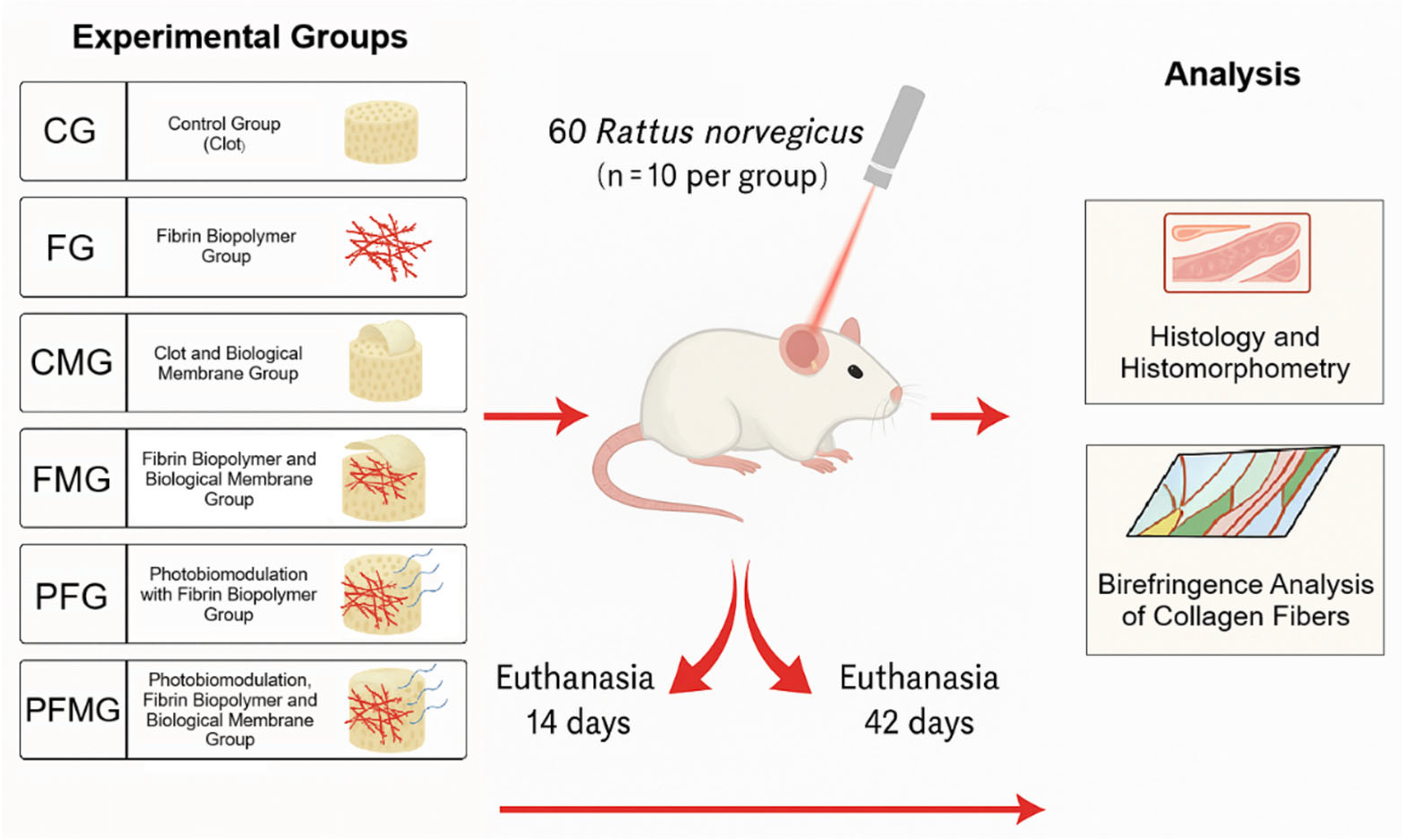

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Aspects

4.2. Selection and Maintenance of the Animals

4.3. Randomization of Experimental Groups and Materials Used

4.4. Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer

4.5. Bovine Bone Cortical Biological Membrane

4.6. Experimental Surgery

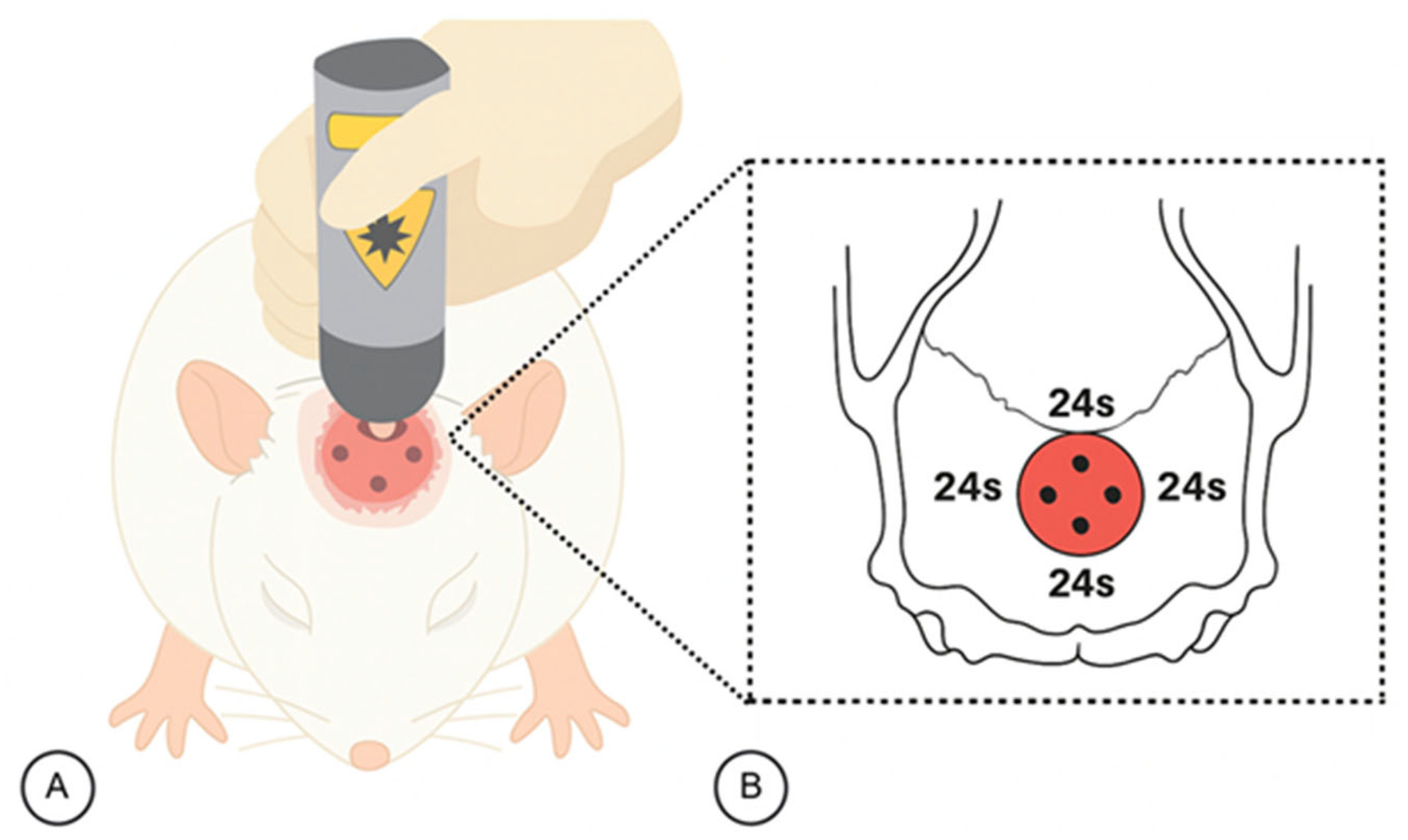

4.7. Protocol for Photobiomodulation Therapy (PBM)

4.8. Surgical Procedure for Tissue Extraction

4.9. Histotechnical Processing

4.10. Histomorphometric Analysis of Defects Stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin and Masson’s Trichrome

4.11. Analysis of the Birefringence of Collagen Content in Bone Defects

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Control group |

| CMG | Clot and membrane group |

| FG | Fibrin biopolymer group |

| FMG | Fibrin biopolymer and membrane group |

| PFG | Photobiomodulation and fibrin biopolymer group |

| PFMG | Photobiomodulation, fibrin biopolymer and membrane group |

| GBR | Guided bone regeneration |

| GaAlAs | Aluminum gallium arsenide diode |

| EDTA | Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid |

| M | Membrane |

| CB | Cortical bone |

| RT | Reaction tissue |

| b | Defect border |

| PBM | Photobiomodulation |

| LLLT | Low-level laser therapy |

References

- Buck, D.W.; Dumanian, G.A. Bone Biology and Physiology. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iaquinta, M.R.; Montesi, M.; Mazzoni, E. Advances in Bone Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecka-Czernik, B.; Rosen, C.J.; Napoli, N. The Role of Bone in Whole-Body Energy Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafage-Proust, M.-H.; Magne, D. Biology of Bone Mineralization and Ectopic Calcifications: The Same Actors for Different Plays. Arch. De Pédiatrie 2024, 31, 4S3–4S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, P.; Monier-Faugere, M.-C.; Geng, Z.; Cohen, D.; Malluche, H.H. Moderately High Consumption of Ethanol Suppresses Bone Resorption in Ovariectomized but Not in Sexually Intact Adult Female Rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1997, 21, 1150–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzalari, N.L. Bone Fracture and Bone Fracture Repair. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 2003–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, B.; Lombardi, G.; Duque, G. Bone and Muscle Crosstalk in Ageing and Disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherry, S.J. Calcium Balance: Considerations for the Bone Response to Exercise. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2024, 39, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Ogurkowska, M. Bone Health and Physical Activity—The Complex Mechanism. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 3400–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, D.M.B.; Figadoli, A.L.d.F.; Alcantara, P.L.; Pomini, K.T.; Santos German, I.J.; Reis, C.H.B.; Rosa Júnior, G.M.; Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Santos, P.S.d.S.; Zangrando, M.S.R.; et al. Biological Behavior of Xenogenic Scaffolds in Alcohol-Induced Rats: Histomorphometric and Picrosirius Red Staining Analysis. Polymers 2022, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos German, I.J.; Pomini, K.T.; Bighetti, A.C.C.; Andreo, J.C.; Reis, C.H.B.; Shinohara, A.L.; Rosa Júnior, G.M.; Teixeira, D.d.B.; Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Buchaim, D.V.; et al. Evaluation of the Use of an Inorganic Bone Matrix in the Repair of Bone Defects in Rats Submitted to Experimental Alcoholism. Materials 2020, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoudis, P.V.; Einhorn, T.A.; Marsh, D. Fracture Healing: The Diamond Concept. Injury 2007, 38, S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Győri, D.S. Research on Bone Cells in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, C.S.; Park, S.Y.; Ethiraj, L.P.; Singh, P.; Raj, G.; Quek, J.; Prasadh, S.; Choo, Y.; Goh, B.T. Role of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, J.W.; Palusińska, M.; Matak, D.; Pietrzak, D.; Nakielski, P.; Lewicki, S.; Grodzik, M.; Szymański, Ł. The Future of Bone Repair: Emerging Technologies and Biomaterials in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Kaur, T.; Chaugule, S.; Yang, Y.-S.; Mago, A.; Shim, J.-H.; John, A.A. Sensors in Bone: Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions. Sensors 2024, 24, 6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Pezeshgi, S.; Sadeghi, R.; Bayan, N.; Farrokhpour, H.; Amanollahi, M.; Bereimipour, A.; Abolghasemi Mahani, A. Clinical Application of Biomaterials in Orbital Implants: A Systematic Review. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisiol, C.H.; Turner, R.T.; Pfaff, J.E.; Hunter, J.C.; Menagh, P.J.; Hardin, K.; Ho, E.; Iwaniec, U.T. Impaired Osteoinduction in a Rat Model for Chronic Alcohol Abuse. Bone 2007, 41, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchaim, R.L.; Andreo, J.C.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Buchaim, D.V.; Dias, D.V.; Daré, L.R.; Roque, D.D.; Roque, J.S. The Action of Demineralized Bovine Bone Matrix on Bone Neoformation in Rats Submitted to Experimental Alcoholism. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2013, 65, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Oyadomari, A.T.; Pomini, K.T.; Della Coletta, B.B.; Shindo, J.V.T.C.; Ferreira Júnior, R.S.; Barraviera, B.; Cassaro, C.V.; Buchaim, D.V.; Teixeira, D.d.B.; et al. Photobiomodulation Therapy Associated with Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer and Bovine Bone Matrix Helps to Reconstruct Long Bones. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, D.M.B.; Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Buchaim, D.V.; Zangrando, M.S.R.; Buchaim, R.L. Update on the Use of 45S5 Bioactive Glass in the Treatment of Bone Defects in Regenerative Medicine. World J. Orthop. 2024, 15, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, H.; Campbell, C.D.; Stemberger, A.; Wriedt-Lübbe, I.; Blümel, G.; Replogle, R.L. Combined Application of Heterologous Collagen and Fibrin Sealant for Liver Injuries. J. Surg. Res. 1984, 36, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, R.J. Optimized Bone Grafting. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 94, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraschini, V.; Louro, R.S.; Son, A.; Calasans-Maia, M.D.; Sartoretto, S.C.; Shibli, J.A. Long-term Survival and Success Rate of Dental Implants Placed in Reconstructed Areas with Extraoral Autogenous Bone Grafts: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2024, 26, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tommasato, G.; Del Fabbro, M.; Oliva, N.; Khijmatgar, S.; Grusovin, M.G.; Sculean, A.; Canullo, L. Autogenous Graft versus Collagen Matrices for Peri-Implant Soft Tissue Augmentation. A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Develioglu, H.; Saraydın, S.; Kartal, Ü.; Taner, L. Evaluation of the Long-Term Results of Rat Cranial Bone Repair Using a Particular Xenograft. J. Oral Implantol. 2010, 36, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, R.; Demer, A.; Ochoa, S.; Arpey, C. Bovine Collagen Xenografts as Cost-Effective Adjuncts for Granulating Surgical Defects. Dermatol. Surg. 2024, 50, 884–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.S.B.; Trajkovski, B.; Zafiropoulos, G.-G. The Response of Human Osteoblasts on Bovine Xenografts with and without Hyaluronate Used in Bone Augmentation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 880–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Ding, M.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Yan, M.; Liu, L.; Ding, C.; Chen, X. Comparative Evaluation of Porcine and Bovine Bone Xenografts in Bone Grafting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2025, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Carroll, M.J. Guided Bone Regeneration Using Bone Grafts and Collagen Membranes. Quintessence Int. 2001, 32, 504–515. [Google Scholar]

- Ashfaq, R.; Kovács, A.; Berkó, S.; Budai-Szűcs, M. Developments in Alloplastic Bone Grafts and Barrier Membrane Biomaterials for Periodontal Guided Tissue and Bone Regeneration Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.D.; Rodriguez, E.; Zhao, K.; Kunda, N.; George, F. Complications Following Alloplastic Chin Augmentation. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2023, 90, S515–S520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrascal-Hernández, D.C.; Martínez-Cano, J.P.; Rodríguez Macías, J.D.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. Evolution in Bone Tissue Regeneration: From Grafts to Innovative Biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, H.J.; Lyngstadaas, S.P.; Rossi, F.; Perale, G. Bone Grafts: Which Is the Ideal Biomaterial? J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, C.; Linde, A.; Gottlow, J.; Nyman, S. Healing of Bone Defects by Guided Tissue Regeneration. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1988, 81, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, I.A.; Monje, A. Guided Bone Regeneration in Alveolar Bone Reconstruction. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 31, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, M.A.H.; Khaleque, M.A.; Kim, G.-H.; Yoo, W.-Y.; Kim, Y.-Y. The Role of Bioceramics for Bone Regeneration: History, Mechanisms, and Future Perspectives. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, M.; Wang, H.; Xie, H.; Song, H. Macrophages in Guided Bone Regeneration: Potential Roles and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1396759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.M.F.; Yassuda, D.H.; Sader, M.S.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Soares, G.D.A.; Granjeiro, J.M. Osteogenic Effect of Tricalcium Phosphate Substituted by Magnesium Associated with Genderm® Membrane in Rat Calvarial Defect Model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 61, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamadjaja, D.B.; Harijadi, A.; Soesilawati, P.; Wahyuni, E.; Maulidah, N.; Fauzi, A.; Rah Ayu, F.; Simanjuntak, R.; Soesanto, R.; Asmara, D.; et al. Demineralized Freeze-Dried Bovine Cortical Bone: Its Potential for Guided Bone Regeneration Membrane. Int. J. Dent. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, J.S.; Oliveira, A.C.; Bastos, A.R.; Fernandes, E.M.; Reis, R.L.; Correlo, V.M.; Shimano, A.C. Collagen Membrane from Bovine Pericardium for Treatment of Long Bone Defect. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2023, 111, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, V.G.; Dall Agnol, G.d.S.; Campista, C.C.C.; Bury, L.L.; Ervolino, E.; Longo, M.; Mulinari-Santos, G.; Levin, L.; Theodoro, L.H. Evaluation of Two Anorganic Bovine Xenogenous Grafts in Bone Healing of Critical Defect in Rats Calvaria. Braz. Dent. J. 2024, 35, e246119. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoro, L.H.; Campista, C.C.C.; Bury, L.L.; de Souza, R.G.B.; Muniz, Y.S.; Longo, M.; Mulinari-Santos, G.; Ervolino, E.; Levin, L.; Garcia, V.G. Comparison of Different Bone Substitutes in the Repair of Rat Calvaria Critical Size Defects: Questioning the Need for Alveolar Ridge Presentation. Quintessence Int. 2024, 55, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Mohd Noor, S.N.F.; Mohamad, H.; Ullah, F.; Javed, F.; Abdul Hamid, Z.A. Advances in Guided Bone Regeneration Membranes: A Comprehensive Review of Materials and Techniques. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2024, 10, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizraji, G.; Davidzohn, A.; Gursoy, M.; Gursoy, U.K.; Shapira, L.; Wilensky, A. Membrane Barriers for Guided Bone Regeneration: An Overview of Available Biomaterials. Periodontol. 2000 2023, 93, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumer. GenDerm. Available online: https://www.baumer.com.br/en/produtos/genderm (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Bighetti, A.C.C.; Cestari, T.M.; Paini, S.; Pomini, K.T.; Buchaim, D.V.; Ortiz, R.C.; Júnior, R.S.F.; Barraviera, B.; Bullen, I.R.F.R.; Garlet, G.P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a New Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer on Socket Bone Healing after Tooth Extraction: An Experimental Pre-clinical Study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.S., Jr.; Silva, D.A.F.d.; Biscola, N.P.; Sartori, M.M.P.; Denadai, J.C.; Jorge, A.M.; Santos, L.D.d.; Barraviera, B. Traceability of Animal Protein Byproducts in Ruminants by Multivariate Analysis of Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry to Prevent Transmission of Prion Diseases. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 25, e148718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pontes, L.G.; Cavassan, N.R.V.; de Barros, L.C.; Ferreira Junior, R.S.; Barraviera, B.; Santos, L.D. dos Plasma Proteome of Buffaloes. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2017, 11, 1600138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.S.S.B.S.; Barraviera, B.; Barraviera, S.R.C.S.; Abbade, L.P.F.; Caramori, C.A.; Ferreira, R.S. A Success in Toxinology Translational Research in Brazil: Bridging the Gap. Toxicon 2013, 69, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Soares, A.; Costa, F.; Rodrigues, V.; Fuly, A.; Giglio, J.; Gallacci, M.; Thomazini-Santos, I.; Barraviera, S.; Barraviera, B.; et al. Biochemical and Biological Evaluation of Gyroxin Isolated from Crotalus Durissus Terrificus Venom. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 17, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braud, S. Snake Venom Proteins Acting on Hemostasis. Biochimie 2000, 82, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiquito, G.C.M. Comparison between Suture and Fibrin Adhesive Derived from Snake Venom for Fixation of Connective Tissue Graft in Correction of Marginal Tissue Recession. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2007, 13, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotnitz, W.D. Fibrin Sealant: Past, Present, and Future: A Brief Review. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomazini-Santos, I.A.; Barraviera, S.R.C.S.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S.; Barraviera, B. Surgical Adhesives. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins 2001, 7, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomazini-Santos, I.A.; Giannini, M.J.S.M.; Toscano, E.; Machado, P.E.A.; Lima, C.R.G.; Barraviera, B. The evaluation of clotting time in bovine thrombin, Reptilase ®, and thrombin-like fraction of Crotalus durissus terrificus venom using bovine, equine, ovine, bubaline and human cryoprecipitates. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins 1998, 4, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbade, L.P.F.; Ferreira, R.S., Jr.; Santos, L.D.d.; Barraviera, B. Chronic Venous Ulcers: A Review on Treatment with Fibrin Sealant and Prognostic Advances Using Proteomic Strategies. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 26, e20190101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Gonçalves, J.B.; Buchaim, D.V.; de Souza Bueno, C.R.; Pomini, K.T.; Barraviera, B.; Júnior, R.S.F.; Andreo, J.C.; de Castro Rodrigues, A.; Cestari, T.M.; Buchaim, R.L. Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Autogenous Bone Graft Stabilized with a New Heterologous Fibrin Sealant. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 162, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.S.; de Barros, L.C.; Abbade, L.P.F.; Barraviera, S.R.C.S.; Silvares, M.R.C.; de Pontes, L.G.; dos Santos, L.D.; Barraviera, B. Heterologous Fibrin Sealant Derived from Snake Venom: From Bench to Bedside—An Overview. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troeltzsch, M.; Troeltzsch, M.; Kauffmann, P.; Gruber, R.; Brockmeyer, P.; Moser, N.; Rau, A.; Schliephake, H. Clinical Efficacy of Grafting Materials in Alveolar Ridge Augmentation: A Systematic Review. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 44, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchaim, D.V.; Rodrigues, A.d.C.; Buchaim, R.L.; Barraviera, B.; Junior, R.S.F.; Junior, G.M.R.; Bueno, C.R.d.S.; Roque, D.D.; Dias, D.V.; Dare, L.R.; et al. The New Heterologous Fibrin Sealant in Combination with Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) in the Repair of the Buccal Branch of the Facial Nerve. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.; Malekshahabi, T.; Shiari, R. Biological Effects of Low Level Laser Therapy. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2014, 5, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, F.N.H.; Gondim, J.O.; Neto, J.J.S.M.; dos Santos, P.C.F.; de Freitas Pontes, K.M.; Kurita, L.M.; de Araújo, M.W.A. Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Bone Regeneration of the Midpalatal Suture after Rapid Maxillary Expansion. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Buchaim, D.V.; Pomini, K.T.; Coletta, B.B.D.; Reis, C.H.B.; Pilon, J.P.G.; Duarte Júnior, G.; Buchaim, R.L. Photobiomodulation Therapy (PBMT) Applied in Bone Reconstructive Surgery Using Bovine Bone Grafts: A Systematic Review. Materials 2019, 12, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoro, L.H.; Caiado, R.C.; Longo, M.; Novaes, V.C.N.; Zanini, N.A.; Ervolino, E.; de Almeida, J.M.; Garcia, V.G. Effectiveness of the Diode Laser in the Treatment of Ligature-Induced Periodontitis in Rats: A Histopathological, Histometric, and Immunohistochemical Study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, F.; Shafaee, H.; Haghpanahi, M.; Bardideh, E. Low-Level Laser Therapy and Laser Acupuncture Therapy for Pain Relief after Initial Archwire Placement. J. Orofac. Orthop./Fortsch. Kieferorthopädie 2024, 85, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, L.C.; Kim, D.S.; Santana da Costa, D.; Fernandes Soutello, H.P.; Salata, T.R.; Sato, L.F.; Takahashi, N.I.; de Souza Gomes, V.; Kondo, P.T.; Lomonaco, G.G.; et al. The Role of Photobiomodulation in the Functional Recovery of Proximal Humerus Fractures: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Protocol. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Gröger, S.; Von Bremen, J.; Martins Marques, M.; Braun, A.; Chen, X.; Ruf, S.; Chen, Q. Photobiomodulation Therapy Assisted Orthodontic Tooth Movement: Potential Implications, Challenges, and New Perspectives. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2023, 24, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; George, R.; Love, R.; Ranjitkar, S. Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation in Reducing Pain and Producing Dental Analgesia: A Systematic Review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 3011–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, X.; Diamanti, E.; Trigas, G.C.; Kalyvas, D.; Kitraki, E. Bone Regeneration in Critical-Size Calvarial Defects Using Human Dental Pulp Cells in an Extracellular Matrix-Based Scaffold. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Fadel, R.; Samarani, R.; Chakar, C. Guided Bone Regeneration in Calvarial Critical Size Bony Defect Using a Double-Layer Resorbable Collagen Membrane Covering a Xenograft: A Histological and Histomorphometric Study in Rats. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, M.; Tahamtan, S.; Shavakhi, M.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Fekrazad, R. The Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Bone Regeneration of Oral and Craniofacial Defects. A Systematic Review of Animal, and in-Vitro Studies. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dan, X.; Chen, H.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Ju, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, L.; Fan, X. Developing Fibrin-Based Biomaterials/Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 40, 597–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori, A.; Ashrafi, S.J.; Vaez-Ghaemi, R.; Hatamian-Zaremi, A.; Webster, T.J. A Review of Fibrin and Fibrin Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 4937–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramires, G.A.D.; Helena, J.T.; Oliveira, J.C.S.D.; Faverani, L.P.; Bassi, A.P.F. Evaluation of Guided Bone Regeneration in Critical Defects Using Bovine and Porcine Collagen Membranes: Histomorphometric and Immunohistochemical Analyses. Int. J. Biomater. 2021, 2021, 8828194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titsinides, S.; Agrogiannis, G.; Karatzas, T. Bone Grafting Materials in Dentoalveolar Reconstruction: A Comprehensive Review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2019, 55, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzepi, M.; Donos, N. Guided Bone Regeneration: Biological Principle and Therapeutic Applications. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2010, 21, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, A.S.; Mikos, A.G. Tissue Engineering Strategies for Bone Regeneration. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2005, 94, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Zhang, Y.F. Osteoinduction. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiati, R.; Paes, J.V.; de Moraes, A.N.; Gava, A.; Agostini, M.; Masiero, A.V.; de Oliveira, M.G.; Pagnoncelli, R.M. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Incorporation of Block Allografts. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, V.J.; Arnabat, J.; Comesaña, R.; Kasem, K.; Ustrell, J.M.; Pasetto, S.; Segura, O.P.; ManzanaresCéspedes, M.C.; Carvalho-Lobato, P. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy after Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Clinical Investigation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, G.J.P.L.; Aroni, M.A.T.; Medeiros, M.C.; Marcantonio, E.; Marcantonio, R.A.C. Effect of Low-level Laser Therapy on the Healing of Sites Grafted with Coagulum, Deproteinized Bovine Bone, and Biphasic Ceramic Made of Hydroxyapatite and Β-tricalcium Phosphate. In Vivo Study in Rats. Lasers Surg. Med. 2018, 50, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, P.J.R.; Barros, P.A.G.; Montagner, P.G.; Provout, M.B.; Martinez, E.F.; Suzuki, S.S.; Garcez, A.S. Can Collagen Membrane on Bone Graft Interfere with Light Transmission and Influence Tissue Neoformation During Photobiomodulation? A Preliminary Study. Photobiomodul Photomed. Laser Surg. 2023, 41, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, N.R.d.; Guerrini, L.B.; Esper, L.A.; Sbrana, M.C.; Dalben, G.d.S.; Soares, S.; Almeida, A.L.P.F.d. Evaluation of Photobiomodulation Therapy Associated with Guided Bone Regeneration in Critical Size Defects. In Vivo Study. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2018, 26, e20170244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Coletta, B.B.; Jacob, T.B.; Moreira, L.A.d.C.; Pomini, K.T.; Buchaim, D.V.; Eleutério, R.G.; Pereira, E.d.S.B.M.; Roque, D.D.; Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Shindo, J.V.T.C.; et al. Photobiomodulation Therapy on the Guided Bone Regeneration Process in Defects Filled by Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Associated with Fibrin Biopolymer. Molecules 2021, 26, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufato, F.C.T.; de Sousa, L.G.; Scalize, P.H.; Gimenes, R.; Regalo, I.H.; Rosa, A.L.; Beloti, M.M.; de Oliveira, F.S.; Bombonato-Prado, K.F.; Regalo, S.C.H.; et al. Texturized P(VDF-TrFE)/BT Membrane Enhances Bone Neoformation in Calvaria Defects Regardless of the Association with Photobiomodulation Therapy in Ovariectomized Rats. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrem Doğan, G.; Demir, T.; Orbak, R. Effect of Low-Level Laser on Guided Tissue Regeneration Performed with Equine Bone and Membrane in the Treatment of İntrabony Defects: A Clinical Study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2014, 32, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, R.E.; Giuliani, A.; Mănescu, A.; Heredea, R.; Hoinoiu, B.; Constantin, G.D.; Duma, V.-F.; Todea, C.D. Osteogenic Potential of Bovine Bone Graft in Combination with Laser Photobiomodulation: An Ex Vivo Demonstrative Study in Wistar Rats by Cross-Linked Studies Based on Synchrotron Microtomography and Histology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, N.R.d.; Guerrini, L.B.; Esper, L.A.; Sbrana, M.C.; Santos, C.C.V.d.; Almeida, A.L.P.F.d. Photobiomodulation and Inorganic Bovine Bone in Guided Bone Regeneration: Histomorphometric Analysis in Rats. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.L.B.; Martinez Gerbi, M.E.; de Assis Limeira, F.; Carneiro Ponzi, E.A.; Marques, A.M.C.; Carvalho, C.M.; de Carneiro Santos, R.; Oliveira, P.C.; Nóia, M.; Ramalho, L.M.P. Bone Repair Following Bone Grafting Hydroxyapatite Guided Bone Regeneration and Infra-Red Laser Photobiomodulation: A Histological Study in a Rodent Model. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009, 24, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiari, S. Photobiomodulation and Lasers. Front. Oral. Biol. 2016, 18, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, R.C.; Ong, A.A.; Albasha, O.; Bass, K.; Arany, P. Photobiomodulation Therapy for Wound Care: A Potent, Noninvasive, Photoceutical Approach. Adv. Skin. Wound Care 2019, 32, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.d.C.A.; Limirio, J.P.J.O.; Zanatta, L.S.A.; Simamoto, V.R.N.; Dechichi, P.; Limirio, P.H.J.O. Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Human Bone Healing in Dentistry: A Systematic Review. Photobiomodul Photomed. Laser Surg. 2022, 40, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berni, M.; Brancato, A.M.; Torriani, C.; Bina, V.; Annunziata, S.; Cornella, E.; Trucchi, M.; Jannelli, E.; Mosconi, M.; Gastaldi, G.; et al. The Role of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Bone Healing: Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sella, V.R.G.; do Bomfim, F.R.C.; Machado, P.C.D.; da Silva Morsoleto, M.J.M.; Chohfi, M.; Plapler, H. Effect of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Bone Repair: A Randomized Controlled Experimental Study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Luna, C.A.; do Couto, M.F.N.; Alves, M.S.A.; de Andrade Hage, C.; de Figueiredo Chaves, R.H.; Guimarães, D.M. Photobiomodulation of Alveolar Bone Healing in Rats with Low-Level Laser and Light Emitting Diode Therapy. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, P.; Azadi, A.; Fekrazad, S.; Wang, H.-L.; Fekrazad, R. The Effect of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Fracture Healing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Animal Studies. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossini, P.S.; Rennó, A.C.M.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Fangel, R.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Lahoz, M.d.A.; Parizotto, N.A. Low Level Laser Therapy (830 nm) Improves Bone Repair in Osteoporotic Rats: Similar Outcomes at Two Different Dosages. Exp. Gerontol. 2012, 47, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim, C.R.; Bossini, P.S.; Kido, H.W.; Malavazi, I.; von Zeska Kress, M.R.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Rennó, A.C.; Parizotto, N.A. Low-Level Laser Therapy Induces an Upregulation of Collagen Gene Expression during the Initial Process of Bone Healing: A Microarray Analysis. J. Biomed. Opt. 2016, 21, 088001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim, C.R.; Bossini, P.S.; Kido, H.W.; Malavazi, I.; von Zeska Kress, M.R.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Parizotto, N.A.; Rennó, A.C. Effects of Low Level Laser Therapy on Inflammatory and Angiogenic Gene Expression during the Process of Bone Healing: A Microarray Analysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 154, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.L.S.; de Carvalho, F.M.d.A.; Pereira Filho, R.N.; Ribeiro, M.A.G.; de Albuquerque-Júnior, R.L.C. Effects of Different Protocols of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Collagen Deposition in Wound Healing. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, R.; Mataliotakis, G.I.; Calori, G.M.; Giannoudis, P. V The Role of Barrier Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration and Restoration of Large Bone Defects: Current Experimental and Clinical Evidence. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgali, I.; Omar, O.; Dahlin, C.; Thomsen, P. Guided Bone Regeneration: Materials and Biological Mechanisms Revisited. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 125, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Ye, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, N.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, H. Photobiomodulation Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Increases P-Akt Levels in Vitro. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magri, A.M.P.; Parisi, J.R.; de Andrade, A.L.M.; Rennó, A.C.M. Bone Substitutes and Photobiomodulation in Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review in Animal Experimental Studies. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2021, 109, 1765–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliar, M.F.R.; Marega, L.F.; Duarte, M.A.H.; Alcalde, M.P.; Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Ferreira Junior, R.S.; Barraviera, B.; Reis, C.H.B.; Buchaim, D.V.; Buchaim, R.L. Photobiomodulation Therapy Improves Repair of Bone Defects Filled by Inorganic Bone Matrix and Fibrin Heterologous Biopolymer. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, D.M.; Leitão, R.F.; Figueiró, S.D.; Góes, J.C.; Lima, V.; Silveira, C.O.; Brito, G.A. Guided Bone Regeneration Produced by New Mineralized and Reticulated Collagen Membranes in Critical-Sized Rat Calvarial Defects. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015, 240, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaroli, A.; Agas, D.; Laus, F.; Cuteri, V.; Hanna, R.; Sabbieti, M.G.; Benedicenti, S. The Effects of Photobiomodulation of 808 Nm Diode Laser Therapy at Higher Fluence on the in Vitro Osteogenic Differentiation of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, A.; Chellini, F.; Giannelli, M.; Nosi, D.; Zecchi-Orlandini, S.; Sassoli, C. Red (635 Nm), Near-Infrared (808 Nm) and Violet-Blue (405 Nm) Photobiomodulation Potentiality on Human Osteoblasts and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Morphological and Molecular In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, L.C.; Suárez, E.A.C.; Bernardo, D.V.; Pinto, I.L.R.; Mantovani, L.O.; Silva, T.I.L.; Jardini, M.A.N.; Santamaria, M.P.; De Marco, A.C. Bone Repair Assessment of Critical Size Defects in Rats Treated with Mineralized Bovine Bone (Bio-Oss®) and Photobiomodulation Therapy: A Histomorphometric and Immunohistochemical Study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjazi, A. A Collagen-Based Amniotic Membrane Scaffold Combined with Photobiomodulation Accelerates Wound Repair in Diabetic Rats through Modulation of Inflammation and Tissue Regeneration. Tissue Cell 2025, 97, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.R.; Abdollahi, S.; Etemadi, A.; Hakimiha, N. Investigating the Effect of Photobiomodulation Therapy With Different Wavelengths of Diode Lasers on the Proliferation and Adhesion of Human Gingival Fibroblast Cells to a Collagen Membrane: An In Vitro Study. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2024, 15, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmeli Baran, S.; Temmerman, A.; Salimov, F.; Ucak Turer, O.; Sapmaz, T.; Haytac, M.C.; Ozcan, M. The Effects of Photobiomodulation on Leukocyte and Platelet-Rich Fibrin as Barrier Membrane on Bone Regeneration: An Experimental Animal Study. Photobiomodul Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, F.A.M.; Marques, M.M.; Cavalcanti, S.C.S.X.B.; Pedroni, A.C.F.; Ferraz, E.P.; Miniello, T.G.; Moreira, M.S.; Jerônimo, T.; Deboni, M.C.Z.; Lascala, C.A. Photobiomodulation as Adjunctive Therapy for Guided Bone Regeneration. A MicroCT Study in Osteoporotic Rat Model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2020, 213, 112053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscatel, M.B.M.; Pagani, B.T.; Trazzi, B.F.d.M.; Reis, C.H.B.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Buchaim, D.V.; Buchaim, R.L. Effects of Photobiomodulation in Association with Biomaterials on the Process of Guided Bone Regeneration: An Integrative Review. Ceramics 2025, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh-Kader, A.; Houreld, N.N. Photobiomodulation, Cells of Connective Tissue and Repair Processes: A Look at In Vivo and In Vitro Studies on Bone, Cartilage and Tendon Cells. Photonics 2022, 9, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oury, F. A Crosstalk between Bone and Gonads. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2012, 1260, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venken, K.; Callewaert, F.; Boonen, S.; Vanderschueren, D. Sex Hormones, Their Receptors and Bone Health. Osteoporos. Int. 2008, 19, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis Limeira, F., Jr.; Barbosa Pinheiro, A.; Marquez de Martinez Gerbi, M.; Pedreira Ramalho, L.; Marzola, C.; Carneiro Ponzi, E.; Soares, A.; Bandeira de Carvalho, L.; Vieira Lima, H.; Oliveira Gonçalves, T.; et al. Assessment of bone repair following the use of anorganic bone graft and membrane associated or not to 830-nm laser light. Lasers Dent. IX 2003, 4950, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchaim, D.V.; Cassaro, C.V.; Shindo, J.V.T.C.; Coletta, B.B.D.; Pomini, K.T.; Rosso, M.P.d.O.; Campos, L.M.G.; Ferreira, R.S., Jr.; Barraviera, B.; Buchaim, R.L. Unique Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer with Hemostatic, Adhesive, Sealant, Scaffold and Drug Delivery Properties: A Systematic Review. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guéhennec, L.; Layrolle, P.; Daculsi, G. A Review of Bioceramics and Fibrin Sealant. Eur. Cell Mater. 2004, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.D.S.; Gregh, S.L.A.; Passanezi, E. Fibrin Adhesive Derived From Snake Venom in Periodontal Surgery. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 2026–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biscola, N.P.; Cartarozzi, L.P.; Ulian-Benitez, S.; Barbizan, R.; Castro, M.V.; Spejo, A.B.; Ferreira, R.S.; Barraviera, B.; Oliveira, A.L.R. Multiple Uses of Fibrin Sealant for Nervous System Treatment Following Injury and Disease. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, M.R.d.; Menezes, F.A.; Santos, G.R.d.; Pinto, C.A.L.; Barraviera, B.; Martins, V.d.C.A.; Plepis, A.M.d.G.; Ferreira Junior, R.S. Hydroxyapatite and a New Fibrin Sealant Derived from Snake Venom as Scaffold to Treatment of Cranial Defects in Rats. Mater. Res. 2015, 18, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. Reporting Animal Research: Explanation and Elaboration for the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, H.; Kawamura, I.; Tokumoto, H.; Tawaratsumida, H.; Ogura, T.; Kuroshima, T.; Ijiri, K.; Taniguchi, N. Fibrin Glue-Coated Collagen Matrix Is Superior to Fibrin Glue-Coated Polyglycolic Acid for Preventing Cerebral Spinal Fluid Leakage after Spinal Durotomy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardulli, M.C.; Lovecchio, J.; Parolini, O.; Giordano, E.; Maffulli, N.; Della Porta, G. Fibrin Scaffolds Perfused with Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 as an In Vitro Model to Study Healthy and Tendinopathic Human Tendon Stem/Progenitor Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, S.; Gabra, H.; Hall, N.J.; Flageole, H.; Illie, B.; Barnett, E.; Kocharian, R.; Sharif, K. A Study of Safety and Effectiveness of Evicel Fibrin Sealant as an Adjunctive Hemostat in Pediatric Surgery. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 34, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröger, S.-V.; Blatt, S.; Sagheb, K.; Al-Nawas, B.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Sagheb, K. Platelet-Rich Fibrin for Rehydration and Pre-Vascularization of an Acellular, Collagen Membrane of Porcine Origin. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PERIOD | CG | CMG | FG | FMG | PFG | PFMG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 days | 40.55 ± 11.25 Bb | 40.71 ± 6.33 Bb | 36.97 ± 5.15 Bb | 42.22 ± 7.85 Bb | 30.86 ± 6.52 Bb | 55.88 ± 2.88 Ba |

| 42 days | 47.13 ± 3.92 Ab | 69.22 ± 3.92 Aa | 56.42 ± 7.31 Ab | 51.68 ± 7.78 Ab | 46.10 ± 5.82 Ab | 69.49 ± 6.73 Aa |

| Experimental Groups | Blood Clot | Fibrin Biopolymer | Biological Membrane | Photobiomodulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG (Control group) | Yes | No | No | No |

| FG (Fibrin group) | No | Yes | No | No |

| CMG (Clot + membrane group) | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| FMG (Fibrin + membrane group) | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| PFG (PBM + fibrin group) | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| PFMG (PBM + fibrin + membrane group) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parameters | Specification |

|---|---|

| Light source | Low-level laser (GaAlAs) |

| Wavelength (nm) | 830 nm (near-infrared) |

| Emission mode | Continuous wave |

| Output power (mW) | 30 mW |

| Power density/Irradiance (mW/cm2) | 258.6 mW/cm2 |

| Energy density/Fluence (J/cm2) | 6 J/cm2 |

| Spot size/Beam area (cm2) | 0.116 cm2 |

| Application time per point (s) | 24 s |

| Number of irradiation points | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moscatel, M.B.M.; Pagani, B.T.; Trazzi, B.F.d.M.; Pascon, T.; Barraviera, B.; Ferreira Júnior, R.S.; Buchaim, D.V.; Eleutério, R.G.; Buchaim, R.L. Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer as a Key Scaffold for Bone Regeneration: Synergistic Effects with Photobiomodulation and Membrane Therapy. Gels 2026, 12, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010056

Moscatel MBM, Pagani BT, Trazzi BFdM, Pascon T, Barraviera B, Ferreira Júnior RS, Buchaim DV, Eleutério RG, Buchaim RL. Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer as a Key Scaffold for Bone Regeneration: Synergistic Effects with Photobiomodulation and Membrane Therapy. Gels. 2026; 12(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoscatel, Matheus Bento Medeiros, Bruna Trazzi Pagani, Beatriz Flávia de Moraes Trazzi, Tawana Pascon, Benedito Barraviera, Rui Seabra Ferreira Júnior, Daniela Vieira Buchaim, Rachel Gomes Eleutério, and Rogerio Leone Buchaim. 2026. "Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer as a Key Scaffold for Bone Regeneration: Synergistic Effects with Photobiomodulation and Membrane Therapy" Gels 12, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010056

APA StyleMoscatel, M. B. M., Pagani, B. T., Trazzi, B. F. d. M., Pascon, T., Barraviera, B., Ferreira Júnior, R. S., Buchaim, D. V., Eleutério, R. G., & Buchaim, R. L. (2026). Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer as a Key Scaffold for Bone Regeneration: Synergistic Effects with Photobiomodulation and Membrane Therapy. Gels, 12(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010056