The Potential of Wild Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Pine Canker Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

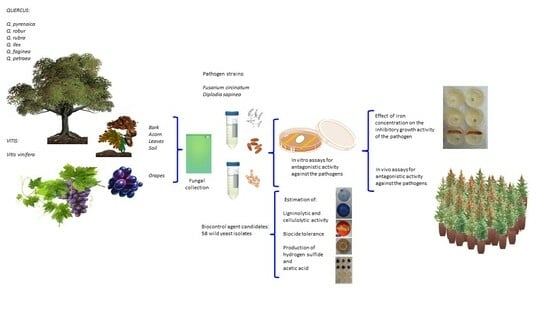

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms and Growth Conditions

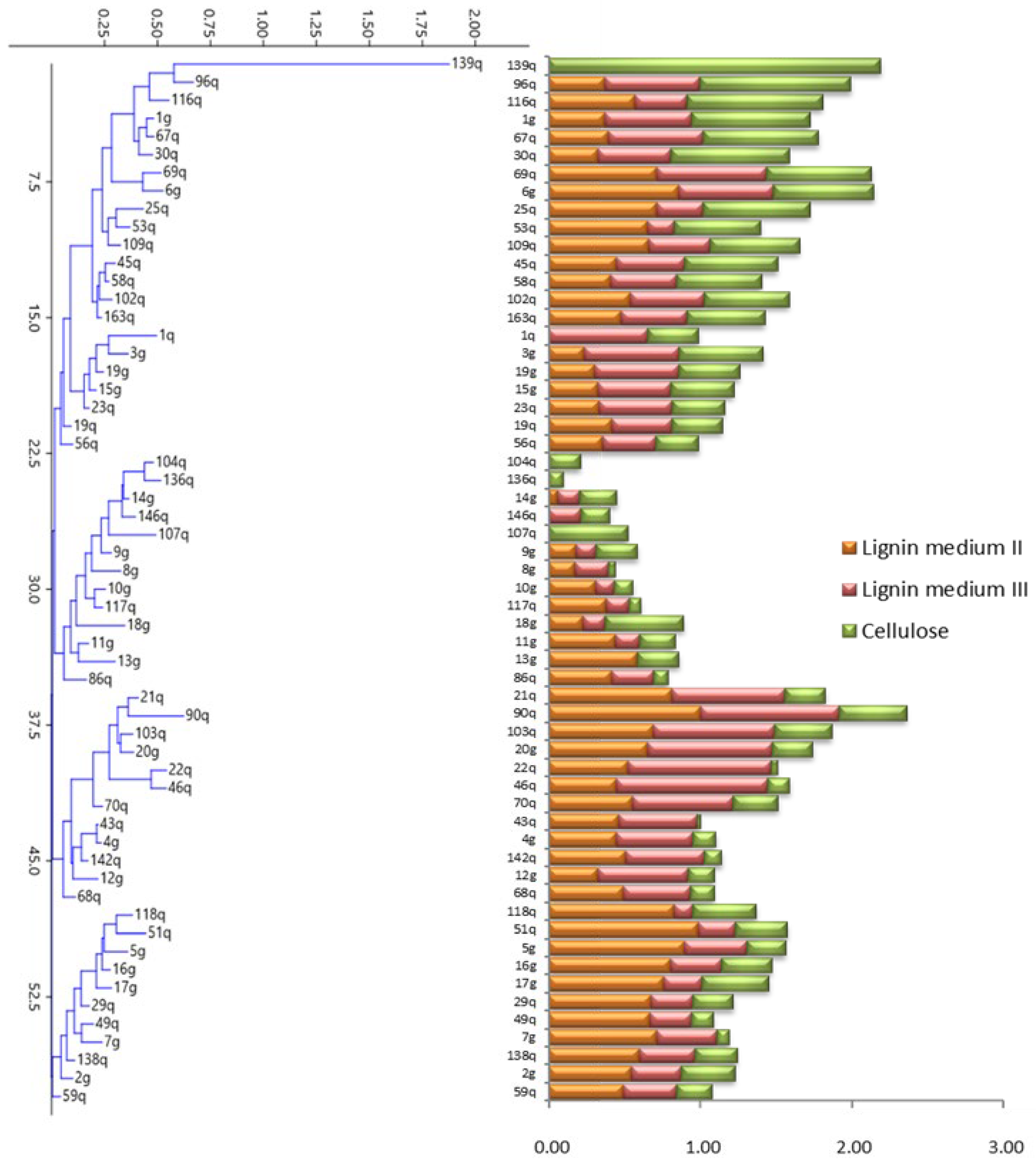

2.2. Estimation of Ligninolytic and Cellulolytic Enzyme Activities

- (i)

- Lignin medium I. Sodium lignosulfonate agar medium: 0.2% sodium lignosulfonate, 2 g of (NH4)2SO4, 1 g of K2HPO4, 1 g of KH2PO4, 0.2 g of MgSO4, 0.1 g of CaCl2, 0.05 g of FeSO4, 0.02 g of MnSO4, 20 g of agar, and 1 L of tap water (pH = 7.0).

- (ii)

- Lignin medium II. Aniline blue agar medium: 10 g of yeast extract, 20 g of glucose, 20 g of agar, 0.1 g of aniline blue, and 1 L of distilled water.

- (iii)

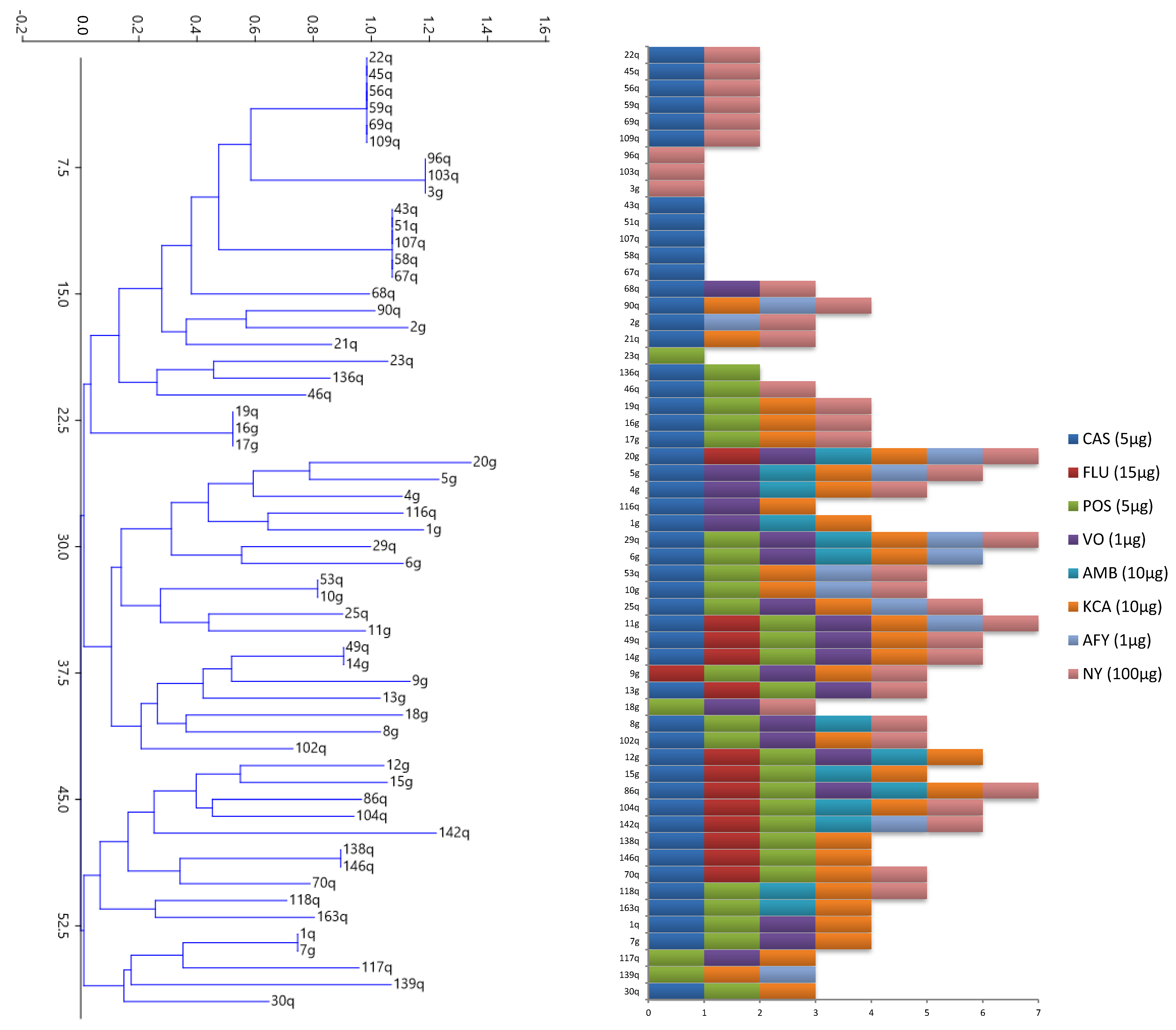

2.3. Determination of Biocide Effectiveness by Inhibition Assay

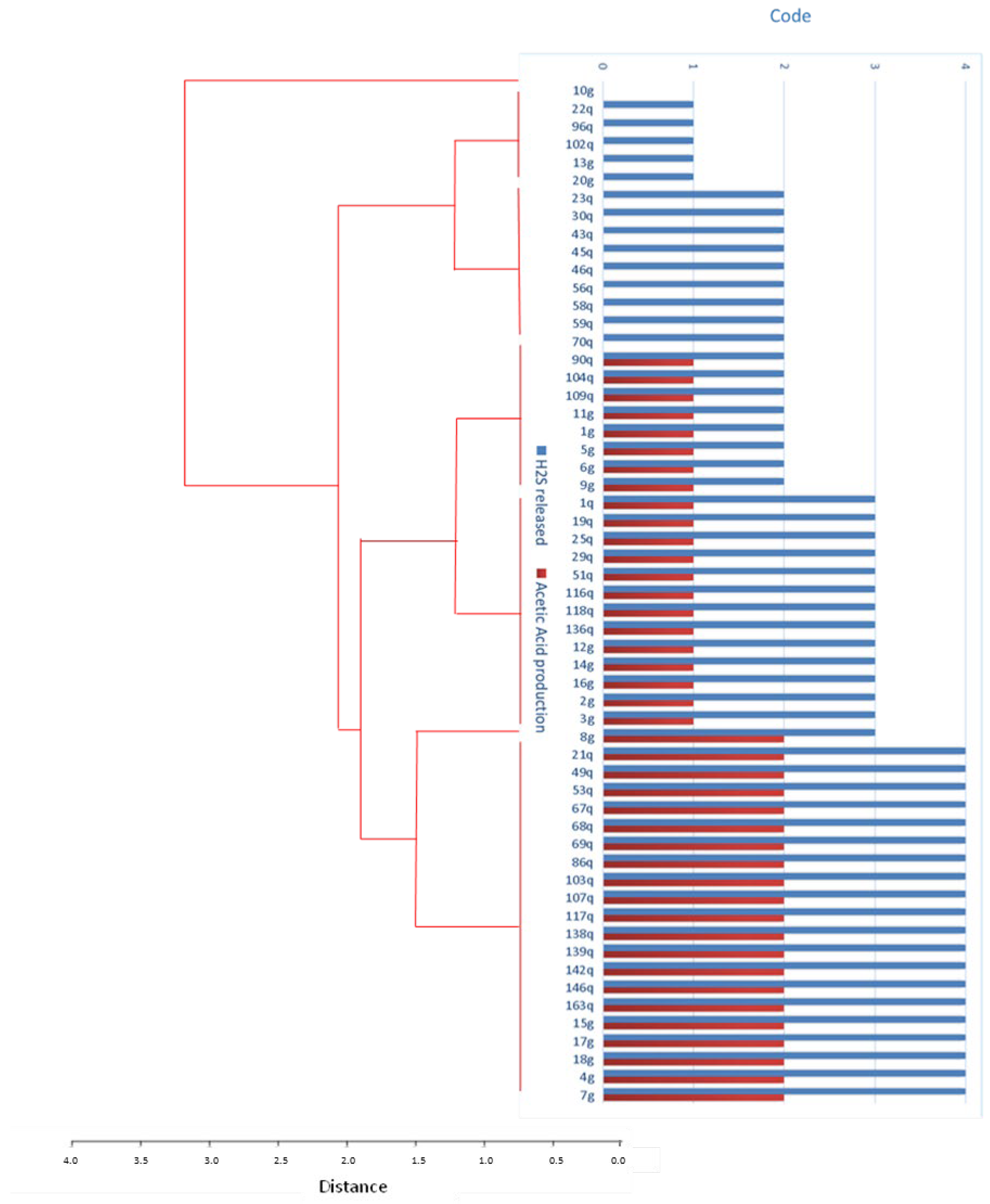

2.4. Yeast Production of Hydrogen Sulfide and Acetic Acid

2.5. In Vitro Assays for Antagonistic Activity

2.6. Effect of Iron Concentration on Yeast Inhibitory Activity

2.7. Phytopathogenicity Test on Plants

2.8. In Vivo Assays for Antagonistic Activity

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Determination of Ligninolytic and Cellulolytic Enzyme Activities

3.2. Determination of Biocide Effectiveness by the Inhibition Assay

3.3. Production of Acetic Acid and Hydrogen Sulfide

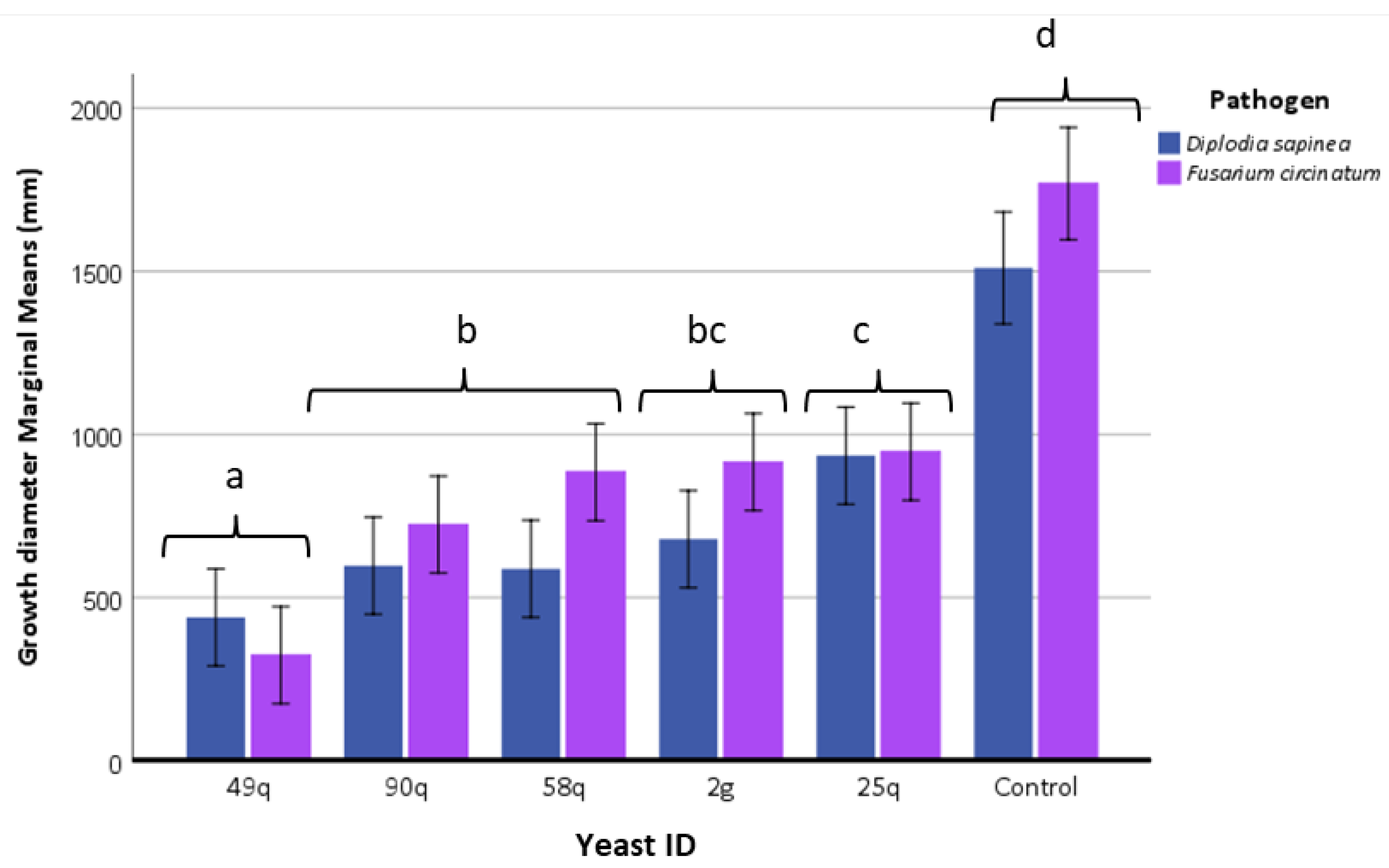

3.4. In Vitro Assays for Antagonistic Activity

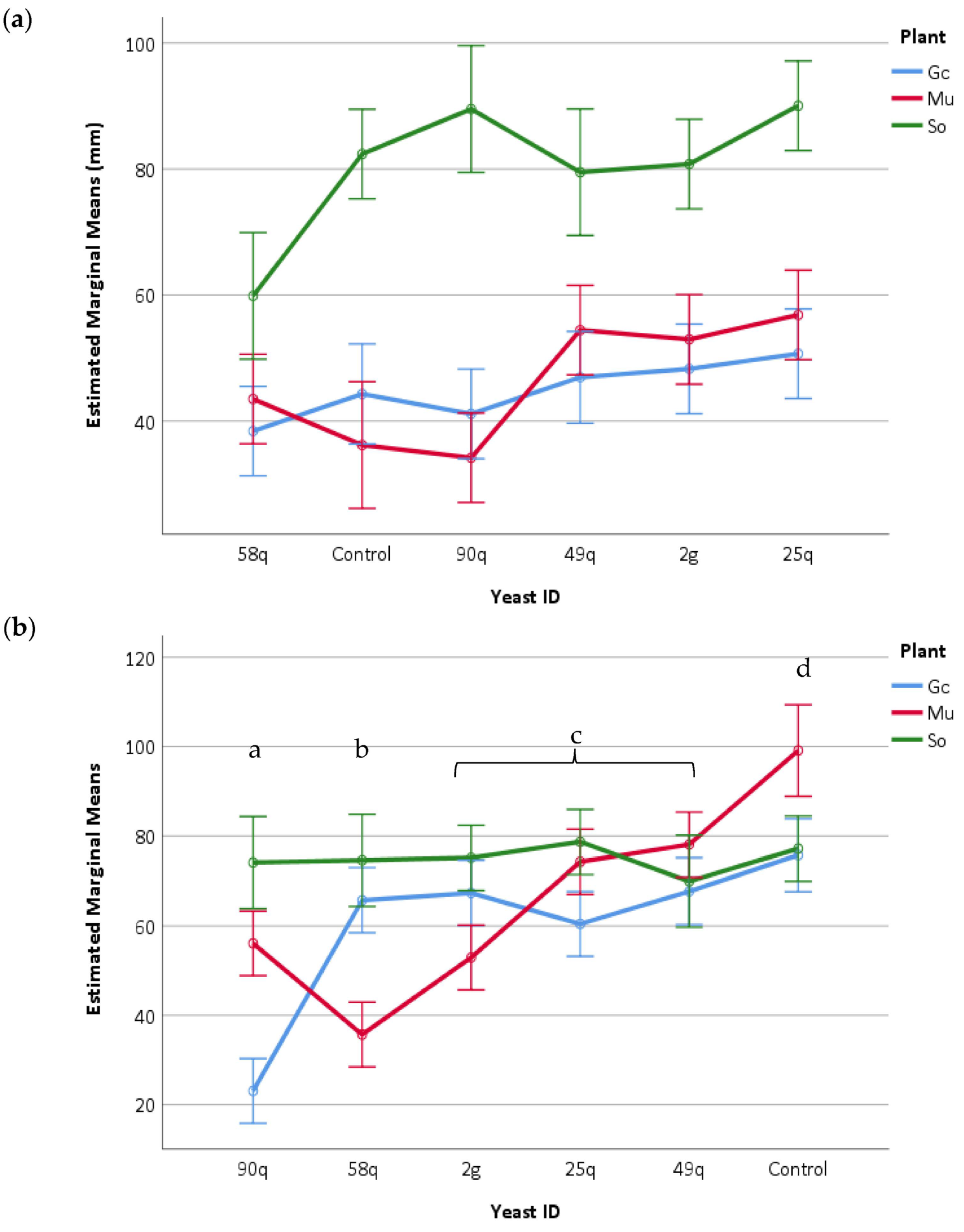

3.5. Phytopathogenicity Test on Higher Plants

3.6. In Vivo Assays for Antagonistic Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Freimoser, F.M.; Rueda-Mejia, M.P.; Tilocca, B.; Migheli, Q. Biocontrol yeasts: Mechanisms and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Text with EEA Relevance. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:309:0071:0086:en:PDF (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Helepciuc, F.E.; Todor, A. Improving the Authorization of Microbial Biological Control Products (MBCP) in the European Union within the EU Green Deal Framework. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataridas, A.; Kanatas, P.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Zannopoulos, S.; Travlos, I. Sustainable Crop and Weed Management in the Era of the EU Green Deal: A Survival Guide. Agronomy 2022, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Henk, D.A.; Briggs, C.J.; Brownstein, J.S.; Madoff, L.C.; McCraw, S.L.; Gurr, S.J. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature 2012, 484, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.C.; Gow, N.A.R.; Gurr, S.J. Tackling emerging fungal threats to animal health, food security and ecosystem resilience. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20160332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desprez-Loustau, M.L.; Robin, C.; Reynaud, G.; Déqué, M.; Badeau, V.; Piou, D.; Husson, C.; Marçais, B. Simulating the effects of a climate-change scenario on the geographical range and activity of forest-pathogenic fungi. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2007, 29, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg, H.I.; O’Donnell, K. New Fusarium species and combinations within the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 1998, 90, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.J.L.; Alves, A.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The Botryosphaeriaceae: Genera and species known from culture. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 76, 51–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvira-Recuenc, M.; Cacciola, S.O.; Sanz-Ros, A.V.; Garbelotto, M.; Aguayo, J.; Solla, A.; Mullett, M.; Drenkhan, T.; Oskay, F.; Aday Kaya, A.G.; et al. Potential Interactions between Invasive Fusarium circinatum and Other Pine Pathogens in Europe. Forests 2020, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturritxa, E.; Ganley, R.J.; Raposo, R.; García-Serna, I.; Mesanza, N.; Kirkpatrick, S.C.; Gordon, T.R. Resistance levels of Spanish conifers against Fusarium circinatum and Diplodia pinea. For. Pathol. 2013, 43, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Escribano, L.; Iturritxa, E.; Aragonés, A.; Mesanza, N.; Berbegal, M.; Raposo, R.; Elvira-Recuenco, M. Root Infection of Canker Pathogens, Fusarium circinatum and Diplodia sapinea, in Asymptomatic Trees in Pinus radiata and Pinus pinaster Plantations. Forests 2018, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday Kaya, A.G.; Yeltekin, Ş.; Lehtijärvi, T.D.; Lehtijärvi, A.; Woodward, S. Severity of Diplodia shoot blight (caused by Diplodia sapinea) was greatest on Pinus sylvestris and Pinus nigra in a plantation containing five pine species. Phytopathol. Mediter. 2019, 58, 1–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisig, O.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Coinfection of a Fungal Pathogen by Two Distinct Double-Stranded RNA Viruses. Virology 1998, 252, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Álvarez, P.; Vainio, E.J.; Botella, L.; Hantula, J.; Diez, J.J. Three mitovirus strains infecting a single isolate of Fusarium circinatum are the first putative members of the family Narnaviridae detected in a fungus of the genus Fusarium. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 2153–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iturritxa, E.; Trask, T.; Mesanza, N.; Raposo, R.; Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Patten, C.L. Biocontrol of Fusarium circinatum Infection of Young Pinus radiata Trees. Forests 2017, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.; Björkman, T.; Ondik, K.; Shoresh, M. Changing Paradigms on the Mode of Action and Uses of Trichoderma spp. for Biocontrol. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2008, 19, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, T.; Rincón, A.M.; Limón, M.C.; Codón, A.C. Mecanismos de biocontrol de cepas de Trichoderma. Int. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz, S.; Aldrete, A.; Alvarado-Rosales, D.; Cibrian, D.; Mendez-Montiel, J. Trichoderma harzianum Rifai as a biocontrol of Fusarium circinatum Nirenberg & O´Donnell in seedlings of Pinus greggii Engelm. ex Parl. in three substrates. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Ambiente 2019, 25, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín García, J.; Zas, R.; Solla, A.; Woodward, S.; Hantula, J.; Vainio, E.J.; Mullett, M.; Morales-Rodríguez, C.; Vannini, A.; Martínez-Álvarez, P.; et al. Environmentally friendly methods for controlling pine pitch canker. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousley, M.A.; Lynch, J.M.; Whipps, J.M. Effect of Trichoderma on plant growth: A balance between inhibition and growth promotion. Microb. Ecol. 1993, 26, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturritxa, E.; Desprez-Loustau, M.L.; García-Serna, I.; Quintana, E.; Mesanza, N.; Aitken, J. Effect of alternative disinfection treatments against fungal canker in seeds of Pinus radiata. Seed Technol. 2011, 33, 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Suzzi, G.; Romano, P.; Ponti, I.; Montuschi, C. Natural wine yeasts as biocontrol agents. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1995, 78, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafati, L.; Vitale, A.; Restuccia, C.; Cirvilleri, G. Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of food-isolated yeast strains against Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest bunch rot of table grape. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Shimon, M.; Yehuda, H.; Cohen, L.; Weiss, B.; Kobeshnikov, A.; Daus, A.; Goldway, M.; Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S. Characterization of extracellular lytic enzymes produced by the yeast biocontrol agent Candida oleophila. Curr. Genet. 2004, 45, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choińska, R.; Piasecka-Jóźwiak, K.; Chabłowska, B.; Dumka, J.; Łukaszewicz, A. Biocontrol ability and volatile organic compounds production as a putative mode of action of yeast strains isolated from organic grapes and rye grains. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipiczki, M. Overwintering of Vineyard Yeasts: Survival of Interacting Yeast Communities in Grapes Mummified on Vines. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00212 (accessed on 1 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Boukaew, S.; Petlamul, W.; Prasertsan, P. Comparison of the biocontrol efficacy of culture filtrate from Streptomyces philanthi RL-1-178 and acetic acid against Penicillium digitatum, in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 158, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturritxa, E.; Hill, A.; Torija, M. Profiling potential brewing yeast from forest and vineyard ecosystems. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 394, 110187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Bueso, G.; Mangieri, N.; Maghradze, D.; Foschino, R.; Valdetara, F.; Cantoral, J.M.; Vigentini, I. Wild Grape-Associated Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Vitis vinifera Fungal Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02025 (accessed on 1 June 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.J.; Gallo, C.R.; Alcarde, V.E.; Godoy, A.; Amorim, H.V. Metodos Para o Controle Microbiologico na Producao de Alcool e Acucar. Published online. 1996. Available online: https://repositorio.usp.br/item/000897338 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Iturritxa, E.; Ganley, R.J.; Wright, J.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Gordon, T.R.; Wingfield, M.J. A genetically homogenous population of Fusarium circinatum causes pitch canker of Pinus radiata in the Basque Country, Spain. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Serna, I. Diplodia Pinea (Desm.) Kickx y Fusarium Circinatum Niremberg & O’Donell, Principales Hongos de Chancro de las Masas Forestales de Pinus Radiata D. Don del País Vasco; Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatearen Argitalpen Zerbitzua: Leioa, Spain, 2011; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10810/12226 (accessed on 1 September 2011).

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Li, B.; Gu, X.; Zhang, X.; Boateng, N.S.; Zhang, H. Molecular dissection of defense response of pears induced by the biocontrol yeast, Wickerhamomyces anomalus using transcriptomics and proteomics approaches. Biol. Control 2020, 148, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Jia, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, H.; Jing, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, F.; Sun, M.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Bacterial and biodeterioration analysis of the waterlogged wooden lacquer plates from the Nanhai No. 1 Shipwreck. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, L.; Anagnostakis, S.L. Solid media containing carboxymethylcellulose to detect cx cellulase activity of microorganisms. Microbiology 1977, 98, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Nigar, S.; Shah, S.; Bashir, S.; Ali, J.; Yousaf, S.; Bangash, J.A. Isolation and identification of cellulose degrading bacteria from municipal waste and their screening for potential antimicrobial activity. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 27, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridi, A.; Cufari, J.A.; Ramondino, D. Isolation and clonal pre-selection of enological Saccharomyces. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 48, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.; Webster, J. Antagonistic properties of species-groups of Trichoderma: II. Production of volatile antibiotics. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1971, 57, 41-IN4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstein, K.; Bußkamp, J.; Langer, G.J.; Schlößer, R.; Parra Rojas, N.M.; Terhonen, E. Sphaeropsis sapinea and associated endophytes in Scots pine: Interactions and Effect on the Host Under Variable Water Content. Front. For. Glob. Change. 2021, 4, p. 655769. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2021.655769 (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Dobson, A. 1. The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms; Yadolah, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; p. 506. ISBN 0-19-850994-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J. Generalized Linear Models; SAGE Publications Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingham, P.J.; Arnst, E.A.; Clarkson, B.D.; Etherington, T.R.; Forester, L.J.; Shaw, W.B.; Sprague, R.; Wiser, S.K.; Peltzer, D.A. The right tree in the right place? A major economic tree species poses major ecological threats. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanyà, J.; Vallejo, V.R. Productivity of Pinus radiata plantations in Spain in response to climate and soil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 195, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CABI. Sphaeropsissapinea (Sphaeropsis blight). CABI Compendium, 16 November 2021; CABI Compendium:19160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Pando, V.; Berbegal, M.; Manzano Muñoz, A.; Iturritxa, E.; Raposo, R. Influence of temperature and moisture duration on pathogenic life history traits of predominant haplotypes of Fusarium circinatum on Pinus spp. in Spain. Phytopath 2021, 111, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Couso, R.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Rivas, R. Mechanisms of action of microbial biocontrol agents against Botrytis cinerea. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, D.; Droby, S. Development of biocontrol products for postharvest diseases of fruit: The importance of elucidating the mechanisms of action of yeast antagonists. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 47, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, P.J.; Zeikus, J.G. Fermentation of cellulose and cellobiose by Clostridium thermocellum in the absence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.K.; Ben-Bassat, A.; Zeikus, J.G. Ethanol production by thermophilic bacteria: Fermentation of cellulosic substrates by cocultures of Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1981, 41, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Haruta, S.; Cui, Z.; Ishii, M.; Igarashi, Y. Effective cellulose degradation by a mixed-culture system composed of a cellulolytic Clostridium and aerobic non-cellulolytic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 51, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Hernandez, S.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Chiquito-Contreras, R.G.; Rincon-Enriquez, G.; Cerdan-Cabrera, C.R.; Hernandez-Montiel, L.G. Biocontrol of postharvest fruit fungal diseases by bacterial antagonists: A review. Agronomy 2019, 9, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospero, S.; Botella, L.; Santini, A.; Robin, C. Biological control of emerging forest diseases: How can we move from dreams to reality? For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.; Pinto, G.; Flores-Pacheco, J.A.; Díez-Casero, J.J.; Cerqueira, A.; Monteiro, P.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Alves, A.; Martín-García, J. Effect of Trichoderma viride pre-inoculation in pine species with different levels of susceptibility to Fusarium circinatum: Physiological and hormonal responses. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NCBI | ID Code | Location | Sample | Host | NCBI | ID Code | Location | Sample | Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida molendinolei | 30q | ULLIVARRI ARRAZUA | Acorn | Qercus faginea | Pichia fermentans | 117q | ESKALMENDI | Bark | Q. ilex |

| Candida subhashii | 102q | ESKALMENDI | Soil | Q. robur | Pichia kudriavzevii | 142q | ESKALMENDI | Bark | Q. ilex |

| Hanseniaspora uvarum | 11g | RIOJA | Grapes | Vitis vinifera | 138q | ESKALMENDI | Acorn | Q. robur | |

| Hyphopichia pseudoburtonii | 6g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 146q | ESKALMENDI | Soil | Q. robur | |

| Kluyveromyces dobzhanskii | 109q | ESKALMENDI | Acorn | Q. ilex | 107q | ESKALMENDI | Bark | Q. ilex | |

| 67q | LANDA | Leaves | Q. robur | 7g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | ||

| 45q | MURGIA | Acorn | Q. robur | Pichia manshurica | 139q | ESKALMENDI | Soil | Q. petraea | |

| 63q | LANDA | Acorn | Q. robur | 136q | ESKALMENDI | Soil | Q. robur | ||

| 69q | LANDA | Acorn | Q. robur | Saccharomyces cariocanus | 56q | IZARRA | Bark | Q. robur | |

| 58q | IZARRA | Leaves | Q. robur | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 20g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | |

| Kluyveromyces marxianus | 23q | ULLIVARRI ARRAZUA | Bark | Q. faginea | Saccharomyces paradoxus | 19q | ESKALMENDI | Soil | Q. ilex |

| Lachancea thermotolerans | 104q | ESKALMENDI | Leaves | Q. faginea | 96q | ESKALMENDI | Soil | Q. petraea | |

| 118q | ESKALMENDI | Acorn | Q. robur | 46q | MURGIA | Soil | Q. robur | ||

| 51q | IZARRA | Soil | Q. robur | 29q | ULLIVARRI ARRAZUA | Leaves | Q. faginea | ||

| 8g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 21q | ULLIVARRI ARRAZUA | Soil | Q. faginea | ||

| 103q | ESKALMENDI | Acorn | Q. ilex | 25q | ULLIVARRI ARRAZUA | Soil | Q. faginea | ||

| 163q | IZKI | Bark | Q. pirenaica | 86q | SALINAS DE LENIZ | Bark | Q. petraea | ||

| 12g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 90q | SALINAS DE LENIZ | Soil | Q. petraea | ||

| 13g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 59q | LANDA | Acorn | Q. robur | ||

| 14g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 43q | MURGIA | Bark | Q. robur | ||

| 15g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 70q | LANDA | Bark | Q. robur | ||

| 16g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 49q | IZARRA | Leaves | Q. robur | ||

| 19g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 53q | IZARRA | Leaves | Q. robur | ||

| Metschnikowia fructicola | 18g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 68q | LANDA | Soil | Q. robur | |

| Metschnikowia pulcherrima | 9g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | Starmerella bacillaris | 4g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera |

| Meyerozyma caribbica | 116q | ESKALMENDI | Bark | Q. ilex | 10g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | |

| Naganishia albida | 5g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | Torulaspora delbrueckii | 22q | ULLIVARRI ARRAZUA | Bark | Q. faginea |

| Ogataea dorogensis | 1q | ARKAUTE | Leaves | Q. robur | 2g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | |

| Wickerhamomyces anomalus | 1g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera | 3g | RIOJA | Grapes | V. vinifera |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iturritxa, E.; Mesanza, N.; Torija, M.-J. The Potential of Wild Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Pine Canker Diseases. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9080840

Iturritxa E, Mesanza N, Torija M-J. The Potential of Wild Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Pine Canker Diseases. Journal of Fungi. 2023; 9(8):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9080840

Chicago/Turabian StyleIturritxa, Eugenia, Nebai Mesanza, and María-Jesús Torija. 2023. "The Potential of Wild Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Pine Canker Diseases" Journal of Fungi 9, no. 8: 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9080840

APA StyleIturritxa, E., Mesanza, N., & Torija, M.-J. (2023). The Potential of Wild Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Pine Canker Diseases. Journal of Fungi, 9(8), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9080840