Abstract

This review brings together the research efforts on salt marsh fungi, including their geographical distribution and host association. A total of 486 taxa associated with different hosts in salt marsh ecosystems are listed in this review. The taxa belong to three phyla wherein Ascomycota dominates the taxa from salt marsh ecosystems accounting for 95.27% (463 taxa). The Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota constitute 19 taxa and four taxa, respectively. Dothideomycetes has the highest number of taxa, which comprises 47.12% (229 taxa), followed by Sordariomycetes with 167 taxa (34.36%). Pleosporales is the largest order with 178 taxa recorded. Twenty-seven genera under 11 families of halophytes were reviewed for its fungal associates. Juncus roemerianus has been extensively studied for its associates with 162 documented taxa followed by Phragmites australis (137 taxa) and Spartina alterniflora (79 taxa). The highest number of salt marsh fungi have been recorded from Atlantic Ocean countries wherein the USA had the highest number of species recorded (232 taxa) followed by the UK (101 taxa), the Netherlands (74 taxa), and Argentina (51 taxa). China had the highest number of salt marsh fungi in the Pacific Ocean with 165 taxa reported, while in the Indian Ocean, India reported the highest taxa (16 taxa). Many salt marsh areas remain unexplored, especially those habitats in the Indian and Pacific Oceans areas that are hotspots of biodiversity and novel fungal taxa based on the exploration of various habitats.

1. Introduction

Salt marsh ecosystems are known for their high productivity, exceeding primary production estimates of species rich ecosystems (e.g., tropical rainforests, coral reefs) [1]. The flora in salt marsh ecosystems is mainly composed of grasses, herbs, and shrubs and these are terrestrial organisms variously adapted to, or tolerant of, a semi-marine environment. Halophytes are a diverse group of plants that have a worldwide distribution, and grow in different climatic regions, wherein soils have high salinity levels [2]. Halophytes are common in temperate and Mediterranean climates, and fewer both in the tropics and at high latitudes [3,4,5,6]. The vegetation in these ecosystems shows the vertical zonation of different communities as tidal submergence decreases with increasing elevation, and species tolerance to changing gradient conditions. Salt marsh vegetation generally increases the attenuation of both tidal currents and waves as they pass over the vegetated area and immobilize elements with their sediments. Furthermore, halophytes serve as a natural buffer, protecting other shoreline ecosystems from human impacts and disturbances. The area provides a habitat and nursery for marine organisms [7]. Worldwide, salt marshes cover an area of 5,495,089 hectare in 43 countries [8].

There are over 500 species of salt marsh plants worldwide [9]. The families Amaranthaceae (subfamilies Chenopodiaceae, Salicornieae), Poaceae, Juncaceae, and Cyperaceae are the major vegetation in salt marsh ecosystems, while the minor components are Plumbaginaceae and Frankeniaceae [3], and are represented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Salinity, latitude, region of the world, the frequency and duration of tidal flooding, substrate, oxygen and nutrient availability, surface elevation, competition among species, disturbance by wrack deposition are interacting factors that influence the species of halophytes in the salt marshes [10,11]. For example, Spartina alterniflora is a dominant grass from mid-tide to high-tide levels in temperate Eastern North America, while Puccinellia dominates in boreal and arctic marshes [10,11].

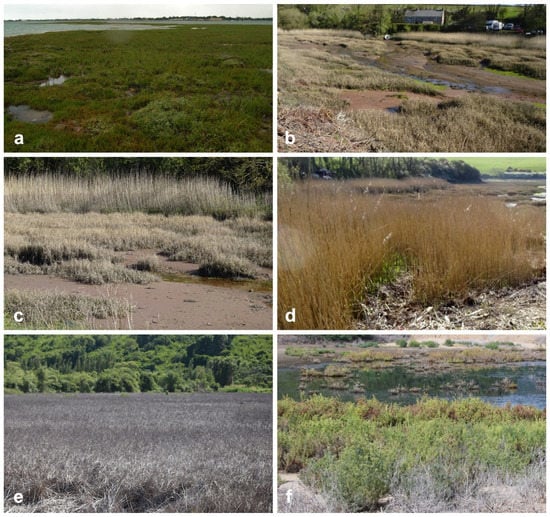

Figure 1.

Salt marsh ecosystems in UK (a–d) and Thailand (e–f). (b–d) Tidal grasses, Spartina townsendii (Poaceae) and Phragmites (Poaceae), dominate the salt marsh in UK (50°49′55.4″ N 0°58′25.1″ W; 51°43′03.1″ N 5°10′24.8″ W); (e) Spartina (Poaceae) (12°22′4.0″ N 99°59′6.7″ E) (f) and Suaeda (Amaranthaceae) (12°10′19.6″ N 99°58′20.3″ E) in tidal marsh areas in southern Thailand.

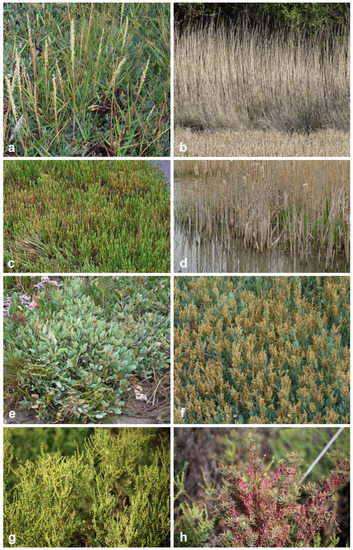

Figure 2.

Halophytes in salt marsh ecosystems: (a) flowering inflorescence of Spartina, (b) Phragmites, (c) Salicornia, (d) Typha, (e,f) Atriplex, and (g,h) Suaeda.

Major studies on halophytes focus on ecology and conservation [12,13,14]. One of these is the decomposition of vascular plant material wherein the detritus breakdown was reviewed in Pomeroy and Wiegert [15], Howarth and Hobbie [16], and Long and Mason [17]. The active decomposition processes in salt marsh ecosystems reflects to the relatively high rates of primary production. Three phases of plant decomposition were noted by Valiela et al. [18]. The early phase involves the leaching of soluble compounds, resulting in a fast rate of weight loss lasting for less than a month. Organic matter breakdown by microorganisms and continuous leaching of decayed products occurs in the second phase that lasts for a year. The last phase lasts for another year when there is a slow decay of refractory materials such as humates and fulvates [19].

The continuous breakdown of detritus into smaller fragments increases the surface-to-volume ratio and this is exposed to further microbial degradation. Bacteria and fungi are key decomposers in the salt marsh ecosystem that are essential for the transformation and recycling of nutrients through the environment. The colonization of fungi on standing dead halophytes commences during the early stages of decomposition before leaf fall to the salt marsh sediment surface [20,21]. The decomposition of the senescent tissues of halophytes by salt marsh fungi is brought about by the direct penetration of the host cell wall and the production of enzymes active in degrading lignocellulosic compounds, such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose [22,23,24,25,26]. Bacterial communities are the major decomposers in the latter stage of decomposition [27,28]. Studies in salt marsh ecosystems not only consider microbial activity and the recycling of nutrients, but also bacterial [29,30] and fungal diversity [20,31,32].

The present review compiles the published data of fungi from halophytes, including their geographical distribution and host association. When compared to other fungal groups, salt marsh fungi are underexplored, and this review brings together the research efforts on these undiscovered habitats and plants. The pertinent literature from bibliographic databases (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar) and published resources on salt marsh fungi documenting halophytes were compiled. Published works, wherein the documented fungal taxa were observed directly from halophytic substrates, are included (Table 1). The different host parts, living and dead, that are either partly or wholly submerged are documented, as well as drift plant portions washed up in salt marsh areas. Salt marsh fungi isolated using cultivation-dependent techniques were not included since it is not known if these fungi were actively growing and reproducing on the halophytes. The taxa were listed based on the recent outline of fungi and fungus-like taxa by Wijayawardene et al. [33]. Since previous works only listed the taxa and the hosts [34,35,36], here we include the plant parts where the fungus was observed, the location (country: state/province) where the host was collected, the life mode of the fungus, and the pertinent literature citations are included (Table 1). The accepted name of the host was based on the webpage of the World Flora Online consortium (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/; accessed on 10 May 2021), GrassBase (https://www.kew.org/data/grasses-db/sppindex.htm; accessed on 10 May 2021) and CRC World Dictionary of Grasses by Quattrocchi [37]. The graphs presented in the next sections summarizes the information from Table 1 and was developed using data visualization tools (Excel Office 365, Tableau Desktop Professional Edition 19.2.2).

Table 1.

Geographical distribution of salt marsh fungi recorded from various halophytes.

2. Taxonomic Classification of Salt Marsh Fungi

2.1. Phyla

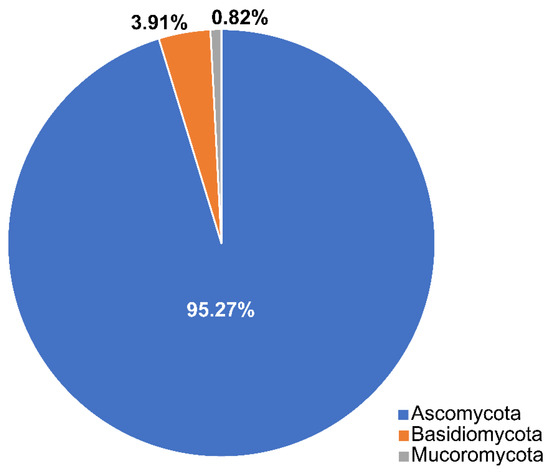

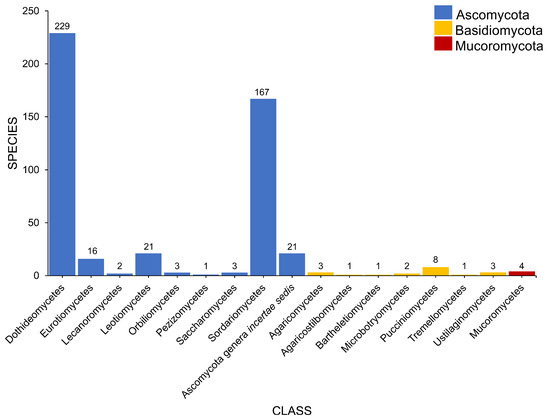

Calado and Barata [34] documented 332 taxa associated with Juncus roemerianus, Phragmites australis, and Spartina spp. In this review, we list 486 taxa that belong to three phyla (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mucoromoycota) (Table 1, Figure 3) and selected species are illustrated in Figure 4. Ascomycota dominates the taxa from salt marsh ecosystems, accounting for 95.27% (463 taxa). Nineteen species in twelve genera (Aecidium, Chaetospermum, Falmingomyces, Merismodes, Nia, Parvulago, Puccinia, Sporobolomyces, Stilbum, Tranzscheliella, Tremella, Uromyces) belong to Basidiomycota (3.91%), while Mucoromycota account for 0.82% (four species) of the salt marsh fungi.

Figure 3.

The distribution of salt marsh fungi among three fungal phyla.

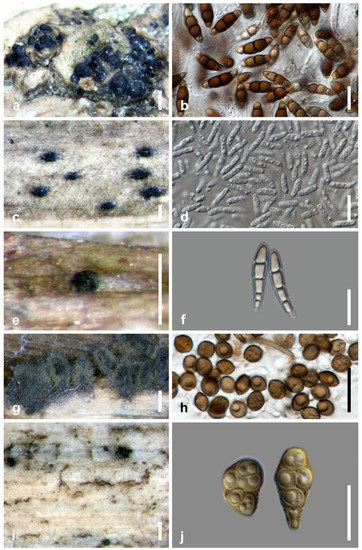

Figure 4.

Salt marsh fungi. (a,b) Halobyssothecium obiones from Atriplex portulacoides; (c,d) Halobyssothecium phragmites from culms of Phragmites sp.; (e,f) Buergenerula spartinae from culms of Spartina sp.; (g,h) Chaetomium sp. from stem of Typha sp.; (i,j) Alternaria sp. from culms of Spartina sp. Scale bars: (a,g) = 500 µm; (b,d,f,h,j) = 20 µm; (c,i) = 200 µm; (e) = 100 µm.

2.2. Class

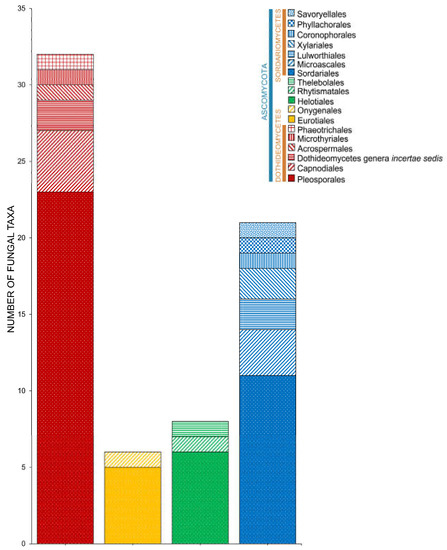

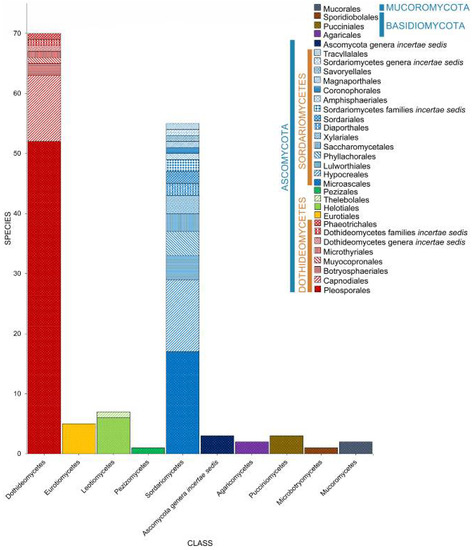

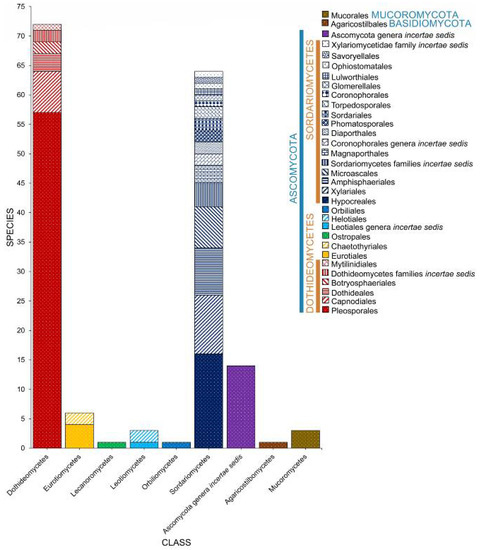

Salt marsh fungi are distributed into 17 classes (Table 1, Figure 5). Dothideomycetes has the highest number of taxa, which comprises 47.12% (229 taxa), followed by Sordariomycetes with 167 taxa (34.36%). Twenty-one species (in 20 genera) can be referred to as Ascomycota genera incertae sedis. The Ascomycetes with the least number of species include Leotiomycetes (21 species, 4.32%), Eurotiomycetes (16 species, 3.29%), Orbiliomycetes (3 species, 0.62%), Saccharomycetes (3 species, 0.62%), Lecanoromycetes (2 species, 0.41%), and Pezizomycetes (1 species, 0.21%).

Figure 5.

The distribution of salt marsh fungi in different fungal classes.

Seven classes represent the Basidiomycota (Figure 5). Puccinomycetes has the highest number of taxa documented (eight species, three genera) followed by Agaricomycetes (three species, two genera), Ustilaginomycetes (three species, three genera), and Microbotryomycetes (two taxa, one genus). Agaricostilbomycetes, Bartheletiomycetes, and Tremellomycetes have one representative taxon each.

The Mucoromoycota account for the taxa Blakeslea trispora, Mucor sp., Rhizopus stolonifera, and Syncephalastrum racemosum [43,48,49].

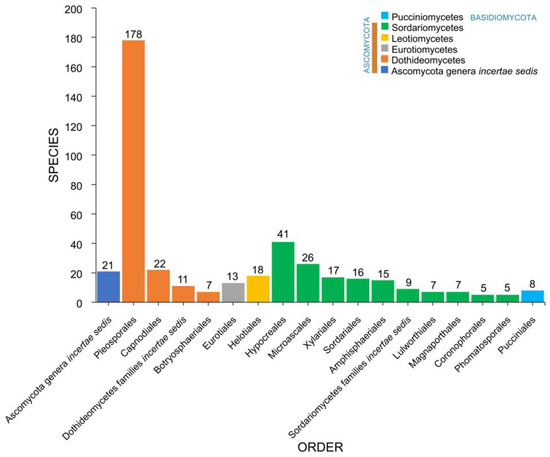

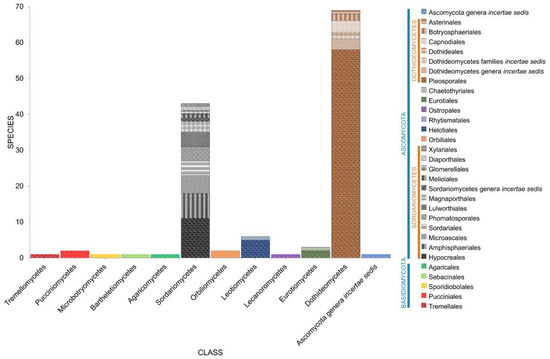

2.3. Orders

Salt marsh fungi recorded from different halophytes were distributed among 48 orders (Table 1, Figure 6). The Pleosporales is the largest order, with 178 taxa recorded followed by Hypocreales (41), Microascales (26), Capnodiales (22), Helotiales (18), Xylariales (17), Sordariales (16), Amphisphaeriales (15), and Eurotiales (13). The remaining 41 orders have less than 10 species (Table 1, Figure 5). Forty-two taxa belong to incertae sedis (Ascomycota genera incertae sedis: 21; Dothideomycetes families incertae sedis: 11; Sordariomycetes families incertae sedis: 9; Xylariomycetidae family incertae sedis: 1).

Figure 6.

The distribution of salt marsh fungi in major fungal orders.

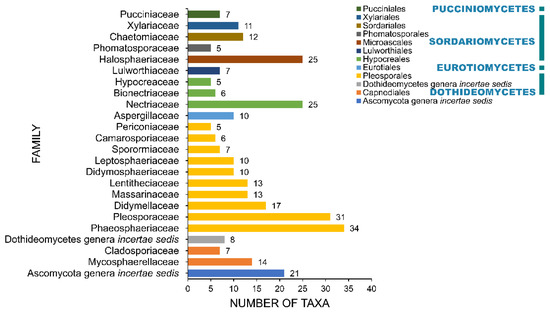

2.4. Families

A total of 108 families and 12 incertae sedis were recorded to be associated with salt marsh fungi (Table 1, Figure 7). Phaeosphaeriaceae and Pleosporaceae account for the largest families with 34 and 31 taxa recorded, respectively. Thirteen families have ten or more than taxa and include Nectriaceae (25), Halosphaeriaceae (25), Didymellaceae (17), Mycosphaerellaceae (14), Lentitheciaceae (13), Massarinaceae (13), Chaetomiaceae (12), Xylariaceae (11), Didymosphaeriaceae (10), Leptosphaeriaceae (10), and Aspergillaceae (10). The remaining 95 families have less than ten species recorded. Forty-four taxa are placed as incertae sedis, wherein 21 of these belong to Ascomycota genera incertae sedis.

Figure 7.

The distribution of salt marsh fungi among major fungal families.

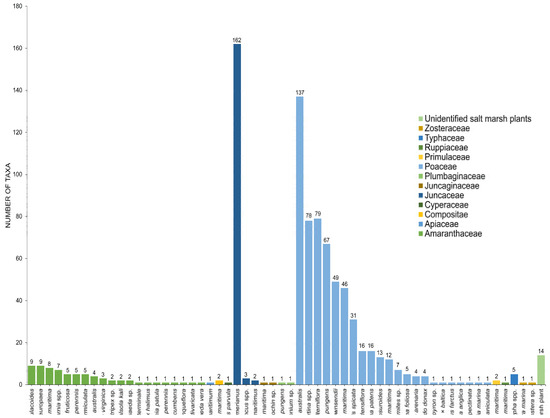

3. Diversity of Fungi in Halophytes

Twenty-seven genera under 11 families (Amaranthaceae, Apiaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Compositae, Juncaceae, Juncaginaceae, Plumbaginaceae, Poaceae, Poaceae, Primulaceae, Ruppiaceae, Typhaceae, Zosteraceae) of halophytes were reviewed for its fungal associates (Table 1, Figure 8). Halophytic species are represented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 8.

The number of taxa observed from different hosts in salt marsh ecosystems.

3.1. Amaranthaceae

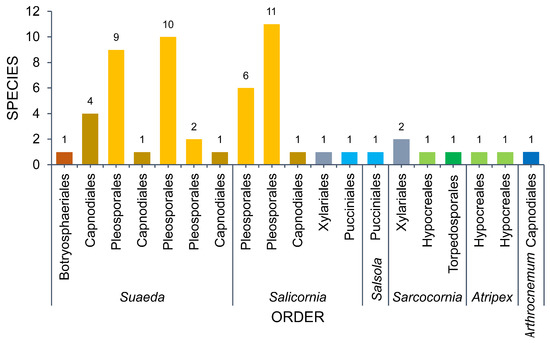

Six genera (Arthrocnemum, Atriplex, Salicornia, Salsola, Sarcocornia, Suaeda) represent the Amaranthaceae. Suaeda and Salicornia are the most studied hosts in Amaranthaceae. Ascomycota account for 96.30% of the 52 taxa recorded in Amaranthaceae (Figure 9, Table 1). Two Pucciniomycetes species, Aecidium suaedae [154] and Uromyces salicorniae [95], represent Basidiomycota. The taxa in Amaranthaceae represent three classes wherein Dothideomycetes accounts for 85.19% (46 taxa), followed by Sordariomycetes with six taxa reported.

Figure 9.

The number of taxa observed from Amaranthaceae.

Fungi associated with Suaeda total 18 taxa. Dothideomycetes was represented by 14 taxa (77.78%), while three taxa were Sordariomycetes (Cryptovalsa suaedicola [144], Fusarium fujikuroi [62], Moheitospora fruticosae [130]) and one taxon of Pucciniomycetes (Aecidium suaedae [154]).

A total of 14 taxa were documented in Salicornia. Eleven of these belong to Dothideomycetes (Pleosporales: 10; Capnodiales: 1), followed by Sordariomycetes (two taxa: Halocryptovalsa salicorniae [145], Tubercularia pulverulenta [35]), and Pucciniomycetes (one taxon: Uromyces salicorniae [95]).

Fungi from Atriplex total 11 taxa (10 genera) and all of these belong to Pleosporales (Dothideomycetes). Sarcocornia harbors seven taxa (six Dothideomycetes, one Sordariomycetes). Only two taxa (Alternaria spp., Stemphylium spp.) and a single taxon (Mycosphaerella salicorniae) were reported from Salsola [35] and Arthrocnemum [35], respectively.

3.2. Poaceae

The association of fungi with grasses have been documented and most of the host plants are members of Poaceae. Ten genera of salt marsh grasses under Poaceae are included in this review wherein Spartina is the most studied of halophytic hosts for direct observation of marine fungi. In addition to Spartina, salt marsh grasses such as Phragmites and Distichlis were well studied also for their fungal associates.

Salt marsh fungi are not well-documented from grasses such as Spartina anglica, S. pectinata, Spergularia marina, Uniola paniculata, Elymus farctus, × Ammocalamagrostis baltica, and Agropyron sp. with one taxon recorded for each host [35]. Furthermore, there are few studies on the fungal composition of Arundo donax (4 taxa) [35] and Ammophila arenaria (four taxa). Marram grass (Ammophila arenaria) is more common in sand dunes and supports quite a diverse fungal community [157,158], while arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) play a key role in the establishment, growth, and survival of plants [159].

3.2.1. Distichlis spicata

Ascomycota dominates the taxa associated with Distichlis spicata (93.55%) wherein 16 and 13 species are members of Dothideomycetes and Sordariomycetes, respectively. Pleosporalean taxa constitute the majority of fungi associated with D. spicata (14 species), followed by Hypocreales with nine species recorded. Puccinia distichlidis and Tranzscheliella distichlidis represent the Basidiomycota. A total of 26 genera were recorded as associates of D. spicata and were mostly observed on senescent and decaying leaves.

3.2.2. Elymus pungens

Sixty-seven taxa were recorded in Elymus pungens and belong to Ascomycota. Most of the taxa belong to Dothideomycetes (32 taxa), followed by Sordariomycetes (21 taxa), Leotiomycetes, and Eurotiomycetes (6 taxa) (Table 1, Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The distribution of fungal taxa associated with Elymus pungens.

3.2.3. Puccinellia maritima

A total of 12 taxa (six Sordariomycetes; the following five Dothideomycetes: Micronectriella agropyri, Lautitia danica, Leptosphaeria pelagica, Septoriella vagans, Paradendryphiella salina; one Leotiomycetes: Thelebolus crustaceus) were recorded in Puccinellia maritima [38]. All the taxa from Sordariomycetes belong to Sordariales (Chaetomium elatum, C. globosum, C. thermophilum, Corynascus sepedonium, Thermothielavioides terrestris, Sordaria fimicola) [38].

3.2.4. Spartina

A total of 149 taxa (141 Ascomycota, 6 Basidiomycota, 2 Mucoromycota) were recorded in Spartina. The majority of the taxa belong to Dothideomycetes (70 taxa), followed by Sordariomycetes (59 taxa). Pleosporaceae and Halosphaeriaceae dominate the fungi documented in Spartina with 19 and 17 taxa recorded, respectively. Spartina alterniflora, S. maritima, and Spartina × townsendii harbor 79, 46, and 49 taxa, respectively (Figure 11, Table 1). A total of 78 taxa were recorded in the unidentified Spartina species. The identification of the Spartina species can be challenging, wherein species are morphologically similar.

Figure 11.

The distribution of fungal taxa associated with Spartina.

Halobyssothecium obiones was recorded from six species of Spartina (S. alterniflora [20,35,52,61,71,74,80,81,82], S. cynosuroides [35], S. densiflora [64], S. maritima [31,54,59,63], S. patens [36], S. townsendii [49,65], and the unidentified Spartina sp. [32,35,36,58,84]), while six Spartina spp. harbors unidentified Mycosphaerella species. Six species (Leptosphaeria pelagica, Lulworthia spp., Phaeosphaeria halima, Phaeosphaeria spartinicola, Phoma spp., Stagonospora spp.) were recorded in five different hosts. The unidentified Spartina species harbors 28 unique species. Amongst the taxa found in Spartina, 32 species can only be found in S. alterniflora, while S. maritima harbors 21 unique species, the most intensively surveyed species.

3.2.5. Phragmites

A total of 138 taxa have been documented in Phragmites (Figure 12, Table 1). Most of the taxa belong to Ascomycota (131 taxa), while six taxa represent the Basidiomycota. Dothideomycetes dominates half of the taxa in Phragmites (71 taxa, 51.45%) followed by Sordariomycetes (44 taxa, 31.88%), Leotiomycetes (6 taxa, 4.35%), Ascomycota genera incertae sedis (5 taxa, 3.62%), Eurotiomycetes (3 taxa, 2.17%), Orbiliomycetes (2 taxon, 1.45%), and Pucciniomycetes (1 taxa, 1.45%). One taxon each were recorded to Agaricomycetes [40], Bartheletiomycetes [41], Lecanoromycetes [39], Microbotryomycetes [39,50], and Tremellomycetes [39,40]. Pleosporalean taxa accounts for the highest number of fungi associated with Phragmites (42.75%, 59 taxa).

Figure 12.

The distribution of fungal taxa associated with Phragmites.

Phragmites australis harbors diverse fungi that totals to 137 taxa (101 genera) [39,40,41,50,79,115]. Seven species (Arthrinium arundinis [62], Halazoon fuscus [87], Halobyssothecium phragmitis [85], Keissleriella linearis [85], Phomatospora dinemasporium [62], Remispora hamata [87], Setoseptoria phragmitis [87]) were recorded in unidentified Phragmites species.

3.3. Juncaceae

Juncus roemerianus, J. maritimus, and an unidentified Juncus species represent Juncaceae. Salt marsh fungi are diverse in Juncus and dominated by Ascomycota, which constitutes 97.58% of the 165 reported taxa (Figure 13, Table 1). Stilbum sp. represented the Basidiomycota, while three taxa (Blakeslea trispora, Mucor sp., Syncephalastrum racemosum) of Mucoromycota were recorded. Dothideomycetes and Sordariomycetes account for the highest number of Juncus-associated fungi with 72 (43.64%) and 64 (38.79%) taxa documented.

Figure 13.

The distribution of fungal taxa associated with Juncus.

Juncus roemerianus has been extensively studied for its associates with 162 documented taxa [32,42,43,60,66,76,77,78,97,98,104,105,110,116,117,118,135,147,148]. Few species were reported to Juncus maritimus that harbor only two taxa (Leptosphaeria albopunctata, Phaeosphaeria neomaritima) [35]. Phaeosphaeria neomaritima [36,52,71,80], P. spartinicola [52], and Monodictys pelagica [35] were observed in an unidentified species of Juncus.

Phragmites australis harbors diverse fungi that totals to 137 taxa (101 genera) [39,40,41,50,79,115]. Seven species (Arthrinium arundinis [62], Halazoon fuscus [87], Halobyssothecium phragmitis [85], Keissleriella linearis [85], Phomatospora dinemasporium [62], Remispora hamata [87], Setoseptoria phragmitis [87]) were recorded in unidentified Phragmites species.

3.4. Other Families

Few reports on salt marsh fungi are from the following hosts: Apiaceae: Crithmum maritimum (one taxon: Phoma sp.), Typhaceae: Typha spp. (five taxa: Arundellina typhae, Chaetomium sp., Magnisphaera spartinae, Pleospora pelagica, Remispora hamata); Compositae: Artemisia maritima (two taxon: Neocamarosporium artemisiae, N. maritimae); Caryophyllaceae: Spergularia marina (one taxon: Cladosporium algarum); Plumbaginaceae: Limonium sp. (one taxon: Mycosphaerella salicorniae); Armeria pungens (one taxon: Mycosphaerella staticicola); Juncaginaceae: Triglochin sp. and T. maritima (one taxon: Stemphylium triglochinicola); Primulaceae: Lysimachia maritima (two taxa: Leptosphaeria orae-maris, Stemphylium vesicarium); Ruppiaceae: Ruppia maritima (one taxon: Flamingomyces ruppiae); and Zosteraceae: Zostera marina (one taxon: Corollospora ramulosa) and Zostera sp. (Asteromyces cruciatus). Alva et al. [160] report Penicillium chrysogenum as an endophyte from Zostera japonica.

Fourteen taxa were documented from unidentified salt marsh plants. All of the taxa belong to Ascomycota (seven Dothideomycetes, five Sordariomycetes, one Eurotiomycetes). Pleosporalean taxa from six families account for half of the taxa (the following seven species: Camarosporium palliatum, C. roumeguerei, Coniothyrium obiones, Halobyssothecium obiones, Periconia sp., Loratospora aestuarii, Pleospora pelvetiae).

4. Geographical Distribution of Salt Marsh Fungi

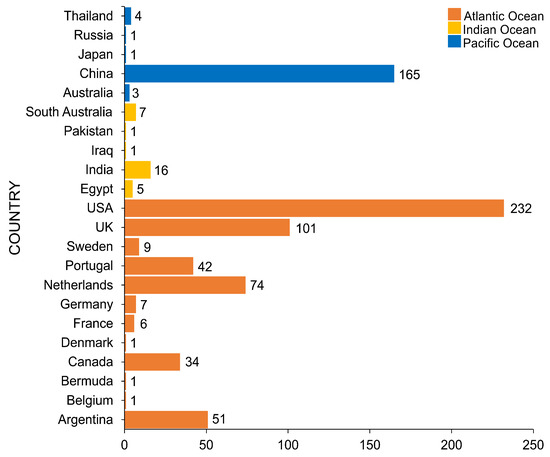

The salt marsh fungi reported are from countries of three major oceans, as documented in Figure 14. The Atlantic Ocean consists of 12 countries, wherein the USA had the highest number of species recorded (232 taxa) followed by the UK (101 taxa), the Netherlands (74 taxa), and Argentina (51 taxa). China had the highest number of salt marsh fungi in the Pacific Ocean with 165 taxa reported, while in the Indian Ocean, India reported the highest taxa (16 taxa). Most of the biodiversity studies documenting salt marsh fungi in the Atlantic Ocean are mostly from the USA and the UK and this reflects the high number of taxa [32,36,38,49,61]. China ranked second with the most number of salt marsh fungal taxa, mainly due to the biodiversity study in Phragmites australis conducted by Poon et al. [41].

Figure 14.

The number of salt marsh fungi reported in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.

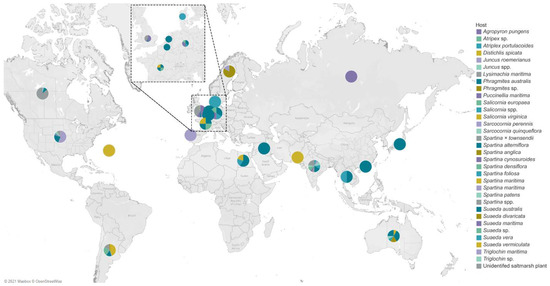

The geographical distribution of salt marsh fungi and the different halophytes are presented in Figure 15. The fungi associated with salt marsh grass Phragmites australis have been studied in different countries (Australia, Belgium, Egypt, France, Germany, China, Iraq, Japan, the Netherlands, South Australia, Thailand). Spartina alterniflora was recorded in countries along the Atlantic (Argentina, Canada, France, USA) and the Indian Ocean (India), but lacks data from countries in the Pacific Ocean.

Figure 15.

Map of countries showing the global distribution of fungal diversity studies in halophytes. The different color of each pie chart represents the hosts, and the angle measured the number of their fungal associates.

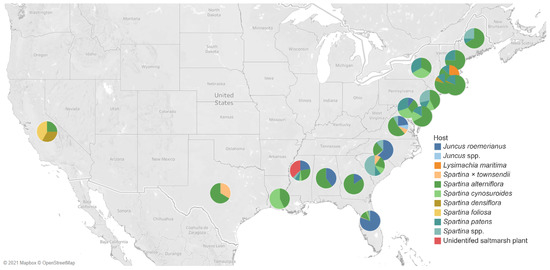

United States of America

Most of the studies of halophytes-associated fungi were concentrated on the United States of America (USA) (Figure 16). Table 1 lists the salt marsh fungi in 20 states. Florida has been the frequently studied, wherein seven hosts (Juncus roemerianus: 108 taxa; Spartina × townsendii: 1; Spartina alterniflora: 16; Spartina cynosuroides: 3; Spartina densiflora: 1; Spartina patens: 2; Spartina spp.: 3) were observed for salt marsh fungi. Six hosts were studied in North Carolina, wherein Juncus roemerianus harbored the highest number of fungi (48 taxa). In Rhode Island, Spartina alterniflora accounts for the highest number of fungi, with 41 taxa recorded.

Figure 16.

Map of the United States of America (USA) showing the distribution of fungal diversity studies of halophytes in different states. The different color of each pie chart represents the hosts, and the angle measured the number of their fungal associates.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Most studies of fungi on salt marsh plants are from Spartina, Juncus, and Phragmites, probably due to the huge biomass generated by these taxa. The mycota of less bulky halophytes (e.g., Limonium, Triglochin, Uniola) and litter from the surrounding sea grass beds washed off to marsh areas (e.g., Zostera japonica, Z. marina, Z. noltii) are also less represented, or these hosts are yet to be explored. The checklist presented in the current study updates the list of Calado and Barata [34] and the inclusion of fungi associated with rarely studied halophytes record 486 taxa worldwide. Ascomycota dominate the taxa (463 taxa) and are comprised mostly of Dothideomycetes with their ability to eject their ascospores forcibly and widely, spore type, the formation of ascomata or ascostromata under a clypeus or just immersed in thin leaves, and an ability to decompose lignocellulose substrates [57,161]. Meyers et al. [162] showed that salt marsh yeasts and the ascomycete, Buergenerula spartinae, produce degradative enzymes and utilize simple carbon and nitrogen compounds. The yeast, Pichia spartinae, produces β-glucosidase and other degradative enzymes. Gessner [74] demonstrated that a number of salt marsh fungi isolated from Spartina alterniflora, Zostera sp., and Z. marina produced enzymes capable of degrading cellulose, cellobiose, lipids, pectin, starch, tannic acid, and xylan and, thus, play a key role in the degradation of storage and structural compounds. Salt marsh fungi might possess high biotransformation and metabolic abilities, which could be related to their ecology.

Basidiomycota (19 taxa) and Mucoromycota (4 taxa) are poorly represented in salt marsh ecosystems as they are in other marine habitats [163]. There are no records of Chytridiomycota listed in the present work and only a few authors detected this group, and other basal fungal lineages, in salt marsh ecosystems using molecular analysis [164,165,166,167]. These groups are worth exploring to determine the overall fungal communities in the salt marsh ecosystems. Many chytrids and other basal fungi are more challenging to cultivate and require different isolation methods (e.g., baiting techniques in liquid culture) than the saprobes, methods that have rarely been applied in the study of saltmarsh plants. When appropriate techniques are used, chytrids and other zoosporic organisms have been reported. For example, the fungal-like organism Phytophthora inundata has been recovered from the halophilic plants Aster tripolium and Salicornia europaea, while P. gemini and P. chesapeakensis occur on Zostera marina, and Salisapilia nakagirii on the decaying litter of Spartina alterniflora (www.marinefungi.org; accessed on 10 May 2021, [163]). Marine chytrids have been isolated from substrates such as seaweeds and mangrove leaves [163].

The taxa listed are mostly saprobes and these can be attributed to the inclusion of salt marsh fungi observed directly from the different host parts, which are mostly submerged decaying substrates. When compared to saprobic fungi in halophytes, few studies have been carried out on the diversity of endophytes and pathogens and their interaction in the salt marsh ecosystems. Surveys on endophytic fungi from halophytes using cultivation-dependent methods coupled with molecular approaches, showed that endophytes were dominated by Ascomycota and a few belonged to Basidiomycota and Zygomycota [168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175]. Pathogenic fungi from salt marsh ecosystems are poorly documented but play a significant role in the dynamics of the ecosystem [176,177,178]. For example, Govers et al. [179] reported that the fungal-like organisms Phytophthora gemini and P. inundata caused widespread infection of the common seagrass species, Zostera marina (eelgrass), across the northern Atlantic and Mediterranean that threatened the conservation and restoration of vegetated marine coastal systems. Likewise, Claviceps purpurea affects the viability of Spartina townsedii in south coast UK salt marshes. Fisher et al. [180] noted that Cl. purpea in the Alabama and Mississippi coastlines rendered the seeds of one of the primary salt marsh grasses sterile. Raybold et al. [181] recorded epidemics of C. purpurea on Spartina anglica in Poole Harbor (UK) and that ergot growth was detrimental to seed production. These underexplored fungal groups are worthy to be explored for their ecological and biotechnological importance.

This shows how salt marsh fungal studies were concentrated in countries in the Atlantic Ocean specifically the USA (232 taxa) and the UK (101 taxa). Many salt marsh areas remain unexplored, especially those in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and these areas are hotspots of biodiversity and novel fungal taxa based on the exploration of various habitats [85,100,163,182,183,184,185,186,187]. Recently, novel species were isolated in halophytes [85,100,145] and further taxa remain to be discovered, isolated, and sequenced, while vast areas worldwide have yet to be surveyed. For example, salt marsh plants are immensely numerous, diverse, and common along the south-east coast of Australia, yet little is known of their fungal associates [188].

The salt marsh vegetation and its fungal associates are adapted to salt stress and inundation and are subjected to extreme environmental conditions such as being periodically wet to different lengths of time leading to drying out at low tides and exposure to high temperatures and drying out at midday. Many are well adapted to prevailing conditions by their fleshy leaves (Suaeda australis), others can tolerate high flooding.

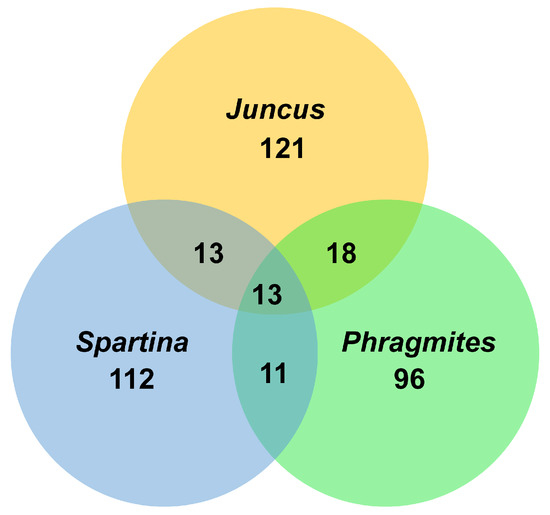

Few data are currently available on the specificity of fungi on their salt marsh hosts. Figure 17 shows the number of fungal taxa recorded from the three commonly studied hosts, Juncus, Phragmites, and Spartina, wherein there is little overlap in the species composition. One of the common species on Spartina plants is undoubtedly Halobyssothecium obiones, while Leptosphaeria pelagica is common. A common ascomycete on Atriplex portulacoides and Suaeda maritima is Decorospora gaudefroyi. Host plants that have been little surveyed for fungi are Limonium vulgare (sea lavender) and Atriplex portulacoides (sea purslane), yet they do support a number of taxa, e.g., Neocamarosporium obiones and Amarenomyces ammophilae. The fungal community reported on Juncus roemerianus in the salt marsh at North Carolina is significantly different from those on Spartina and Phragmites. It remains to be seen if this is due to the host plant or its geographical location.

Figure 17.

Venn diagram showing the association of salt marsh fungi from commonly studied halophytes.

Another groups of fungi that have not been fully studied in the salt marsh habitat are yeasts, as these also require specific techniques for their isolation from the water column or from plant tissue. Spencer et al. [189] recovered a number of yeasts from the vicinity of Spartina townsendii, as follows: very numerous Cryptococcus spp.; Trichosporon cutaneum; Trichosporon pullulans; the relatively rare species, Metschnikowia bicuspidata and Cryptococcus flavus; and Saturnospora ahearnii [190]. Although marine yeasts are common in sea water and deep seawater vents [163], their large-scale sampling in salt marshes remains a challenge for the future.

Currently, the salt marsh ecosystem has been threatened both by global warming and human activity. Sea-level rises brought about by climate change alter the location and character of the land–sea interface wherein salt marsh vegetation moves upward and inland. The increase in the sea level may not lead to the loss of coastal marshes, but the resiliency will depend on the ability of halophytes to migrate upland. Susceptible areas are organogenic marshes and areas where sediment is limited, potentially leading to catastrophic shifts and marsh loss. In this paper, a total of 57 plant taxa under 27 genera were reviewed for their fungal associates. The halophytes included here are only approximately 11% of the total number of species of salt marsh plants worldwide. Thus, many salt marsh fungi await discovery with wider host plant sampling and the use of a wider range techniques for their isolation. For this reason, it is imperative to study the halophytic fungi to document not just biodiversity but also to discover novel taxa restricted only to this kind of habitat.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.S.C., K.D.H. and E.B.G.J.; methodology: M.S.C., K.D.H. and E.B.G.J.; formal analysis and investigation: M.S.C., K.D.H. and E.B.G.J.; resources: K.D.H. and E.B.G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.C.; writing—review and editing, K.D.H., E.B.G.J. and I.P.; supervision, K.D.H. and E.B.G.J.; funding acquisition, K.D.H. and E.B.G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

K.D.H. thanks the Thailand Research Fund for the grant entitled “Impact of climate change on fungal diversity and biogeography in the Greater Mekong Subregion” (Grant No. RDG6130001). E.B.G.J. is supported under the Distinguished Scientist Fellowship Program (DSFP), King Saud University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

M.S.C. is grateful to the Mushroom Research Foundation and the Department of Science and Technology—Science Education Institute (Philippines). K.D.H. thanks Chiang Mai University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bertness, M.D. Atlantic Shorelines: Natural History and Ecology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, M.; Altay, V.; Altundağ, E.; Gücel, S. Halophytic plant diversity of unique habitats in Turkey: Salt mine caves of Çankırı and Iğdır. In Halophytes for Food Security in Dry Lands; Khan, M.A., Ozturk, M., Gul, B., Ahmed, M.Z., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, P. The saltmarsh biota. In Saltmarsh Ecology; Adam, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 72–145. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, K.B. Plant and animal communities of Pacific North American salt marshes. In Wet Coastal Formations; Chapman, V.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976; pp. 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Saenger, P.; Specht, M.M.; Specht, R.L.; Chapman, V.J. Mangal and coastal salt-marsh communities in Australasia. In Wet Coastal Ecosystems; Chapman, V.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; pp. 293–345. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, K.B. Coastal salt marsh. In Terrestrial Vegetation of California; Barbour, M.G., Major, J., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 263–294. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; D’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcowen, C.J.; Weatherdon, L.V.; Van Bochove, J.W.; Sullivan, E.; Blyth, S.; Zockler, C.; Stanwell-Smith, D.; Kingston, N.; Martin, C.S.; Spalding, M.; et al. A global map of saltmarshes. Biodivers. Data J. 2017, 5, 11764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silliman, B.R. Salt marshes. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R348–R350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teal, J.M. Salt marshes and mud flats. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences; Thorpe, S.A., Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, C.T. Salt marsh vegetation. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences; Thorpe, S.A., Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 2487–2490. [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt, A.; de Groot, A.; Smit, C.; Pétillon, J. European salt marshes: Ecology and conservation in a changing world. J. Coast. Conserv. 2017, 21, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, A.J. Development and structure of salt marshes: Community patterns in time and space. In Concepts and Controversies in Tidal Marsh Ecology; Weinstein, M.P., Kreeger, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, S.C.; Callaway, R.M. Salt marsh plant zonation: The relative importance of competition and physical factors. Ecology 1992, 73, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, L.R.; Darley, W.M.; Dunn, E.L.; Gallagher, J.L.; Haines, E.B.; Whitney, D.M. Primary production. In The Ecology of Salt Marsh; Pomeroy, L.R., Wiegert, R.G., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, R.W.; Hobbie, J.E. The Regulation of Decomposition and Heterotrophic Microbial Activity in Salt Marsh Soils: A Review; Kennedy, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Long, S.P.; Mason, C.F. Saltmarsh Ecology; Blackie: Glasgow, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Valiela, I.; Teal, J.M.; Allen, S.D.; Van Etten, R.; Goehringer, D.; Volkmann, S. Decomposition in salt marsh ecosystems: The phases and major factors affecting disappearance of above-ground organic matter. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1985, 89, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, L.R.; Imberger, J. The physical and chemical environment. In The Ecology of Salt Marsh; Pomeroy, L.R., Weigert, R.G., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gessner, R.V.; Goos, R.D. Fungi from decomposing Spartina alterniflora. Can. J. Bot. 1973, 51, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, R.V.; Goos, R.D.; Sieburth, J.M.N. The fungal microcosm of the internodes of Spartina alterniflora. Mar. Biol. 1972, 16, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, R.; Newell, S.Y.; Maccubbin, A.E.; Hodson, R.E. Relative contributions of bacteria and fungi to rates of degradation of lignocellulosic detritus in salt-marsh sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 48, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergbauer, M.; Newell, S.Y. Contribution to lignocellulose degradation and DOC formation from a salt marsh macrophyte by the ascomycete Phaeosphaeria spartinicola. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1992, 86, 34–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, R.; Maccubbin, A.E.; Hodson, R.E. Preparation, characterization, and microbial degradation of specifically radiolabeled [C] lignocelluloses from marine and freshwater macrophytes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 47, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.I.; Alber, M.; Hollibaugh, J.T. Ascomycete fungal communities associated with early decaying leaves of Spartina spp. from central California estuaries. Oecologia 2010, 162, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccubbin, A.E.; Hodson, R.E. Mineralization of detrital lignocelluloses by salt marsh sediment microflora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1980, 40, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.Y.; Porter, D. Microbial secondary production from salt marsh-grass shoots, and its known and potential fates. In Concepts and Controversies in Tidal Marsh Ecology; Weinstein, M.P., Kreeger, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, S.Y.; Fallon, R.D.; Miller, J.D. Decomposition and microbial dynamics for standing, naturally positioned leaves of the salt-marsh grass Spartina alterniflora. Mar. Biol. 1989, 101, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, E.G.; Baraza, E.; Smit, C.; Berg, M.P.; Salles, J.F. Salt marsh elevation drives root microbial composition of the native invasive grass Elytrigia atherica. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, E.; Liu, C.; Jousset, A.; Salles, J.F. Functionality of root-associated bacteria along a salt marsh primary succession. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calado, M.d.L.; Carvalho, L.; Barata, M.; Pang, K.L. Potential roles of marine fungi in the decomposition process of standing stems and leaves of Spartina maritima. Mycologia 2019, 111, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus and Spartina: New marine species of Anthostomella, with a list of marine fungi known on Spartina. Mycol. Res. 2002, 106, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Al-ani, L.K.T.; Tedersoo, L.; Haelewaters, D.; Rajeshkumar, K.C.; Zhao, R.; Aptroot, A.; Leontyev, D.V.; Ramesh, K.; et al. Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 1–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, M.d.L.; Barata, M. Salt marsh fungi. In Marine Fungi and Fungal-like Organisms; Jones, E.B.G., Pang, K.L., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 345–381. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. Marine Mycology: The Higher Fungi; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gessner, R.V.; Kohlmeyer, J. Geographical distribution and taxonomy of fungi from salt marsh Spartina. Can. J. Bot. 1976, 54, 2023–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchi, U. CRC World Dictionary of Grasses; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Apinis, A.E.; Chesters, C.G.C. Ascomycetes of some salt marshes and sand dunes. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1964, 47, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryckegem, G.; Verbeken, A. Fungal ecology and succession on Phragmites australis in a brackish tidal marsh. I. Leaf sheaths. Fungal Divers. 2005, 19, 157–187. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryckegem, G.; Verbeken, A. Fungal ecology and succession on Phragmites australis in a brackish tidal marsh. II. Stems. Fungal Divers. 2005, 20, 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, M.O.K.; Hyde, K.D. Biodiversity of intertidal estuarine fungi on Phragmites at Mai Po Marshes, Hong Kong. Bot. Mar. 1998, 41, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 7. Tiarosporella halmyra sp. nov. Mycotaxon 1996, 59, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, J.W.; Hunter, I.L. Fungi associated with the decomposition of the Black Rush, Juncus roemerianus, in South Florida. Mycologia 1979, 71, 322–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United State Department of Agriculture Crops Research Division. Index of Plant Diseases in the United States: Agriculture Handbook; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Brunaud, P. Champignons nouvellement obsrevés aux environs de Saintes, Charente-inférieure. J. Hist. Nat. Bord Sud. Oust. Bord. 1888, 7, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lobik, A.I. Materialen zur Mykoflora des Terskikreises. Morbi Plant. Leningr. 1928, 17, 157–199. [Google Scholar]

- Elíades, L.A.; Voget, C.E.; Arambarri, A.M.; Cabello, M.N. Fungal communities on decaying saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) in Buenos Aires province (Argentina). Sydowia 2007, 59, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.D.; Whitney, N.J. Fungi of the Bay of Fundy V: Fungi from living species of Spartina Schreber. Proc. Nov. Scotian Inst. Sci. 1983, 33, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, P.J. The possible role of pathogenic fungi in die-back of Spartina townsendii agg. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1959, 42, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryckegem, G.; Gessner, M.O.; Verbeken, A. Fungi on leaf blades of Phragmites australis in a brackish tidal marsh: Diversity, succession, and leaf decomposition. Microb. Ecol. 2007, 53, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus 12. Two new species of Mycosphaerella and Paraphaeosphaeria (Ascomycotina). Bot. Mar. 1999, 42, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borse, B.D.; Bhat, D.; Borse, K.; Tuwar, A.; Pawar, N. Marine fungi of India (Monograph); Broadway Book Centre: Panaji, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. Bermuda marine fungi. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1977, 68, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, M. Fungi on the halophyte Spartina maritima in salt marshes. In Fungi in Marine Environments; Hyde, K.D., Ed.; Fungal Diversity Press: Hong Kong, China, 2002; pp. 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.K.; Campbell, J. Marine fungal diversity: A comparison of natural and created salt marshes of the north-central Gulf of Mexico. Mycologia 2010, 102, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, A.; Newell, S.Y.; Moreta, J.I.L.; Moran, M.A. Analysis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of rRNA genes in fungal communities in a southeastern U.S. salt marsh. Microb. Ecol. 2002, 43, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, A.; Newell, S.Y.; Butler, M.; Biers, E.J.; Hollibaugh, J.T.; Moran, M.A. Dynamics of bacterial and fungal communities on decaying salt marsh grass. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6676–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.K. Marine Fungi of U.S. GULF of Mexico Barrier Island Beaches: Biodiversity and Sampling Strategy; The University of Southern Mississippi: Hattiesburg, MS, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Calado, M.d.L.; Carvalho, L.; Pang, K.L.; Barata, M. Diversity and ecological characterization of sporulating higher filamentous marine fungi associated with Spartina maritima (Curtis) Fernald in two Portuguese salt marshes. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 70, 612–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 11. More new ascomycetes. Can. J. Bot. 1998, 76, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, R.V.; Goos, R.D. Fungi from Spartina alterniflora in Rhode Island. Mycologia 1973, 65, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansford, C.G. Australian Fungi. II. New species and revisions. Proc. Linn. Soc. N. S. W. 1954, 79, 97–141. [Google Scholar]

- Barata, M. Marine fungi from Mira River salt marsh in Portugal. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2006, 23, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, N.I.; Arambarri, A.M. Hongos marinos lignícolas de la laguna costera de Mar Chiquita (provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina). L. Ascomycotina y Deuteromycotina sobre Spartina densiflora. Darwiniana 1998, 35, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.B.G. Marine fungi. I. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1962, 45, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 8. New bitunicate ascomycetes. Can. J. Bot. 1996, 74, 1830–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.W.; Hughes, G.C. Robillarda phragmitis Cunnell in estuarine waters. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1960, 43, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, A.B. Host Index of the Fungi of North America; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Saccardo, P.A. Fungi Gallici lecti a cl. viris P. Brunaud, Abb. Letendre, A. Malbranche, J. Therry, vel editi in Mycotheca Gallica C. Roumeguèri. Series II. Michelia 1880, 2, 39–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S. Contributions to the fungi of West Pakistan. VI. Biol. Lahore 1967, 13, 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.W.; Sparrow, F.K. Fungi in Oceans and Estuaries; Cramer: Weinheim, Germany, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.B.G. Marine fungi: II. Ascomycetes and deuteromycetes from submerged wood and drift Spartina. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, R.V. Seasonal occurrence and distribution of fungi associated with Spartina alterniflora from a Rhode Island estuary. Mycologia 1977, 69, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, R.V. Degradative enzyme production by salt-marsh fungi. Bot. Mar. 1980, 23, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaap, O. Weitere Beiträge zur Pilzflora der nordfriesischen Inseln. Schr. Des Nat. Ver. Für Schleswig-Holst. 1907, 14, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus 9. New obligate and facultative marine ascomycotina. Bot. Mar. 1997, 40, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. New marine and terrestrial ascomycetes. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus 2. New dictyosporous Ascomycetes. Bot. Mar. 1995, 38, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadatha, B.; Calabon, M.S.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G. Molecular data reveals a new holomorphic marine fungus, Halobyssothecium estuariae, and the asexual morph of Keissleriella phragmiticola. Mycology 2020, 11, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.W. Marine Fungi. I. Leptosphaeria and Pleospora. Mycologia 1956, 48, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D. Ecological studies on Leptospheria discors, a graminicolous fungus of salt marshes. Nov. Hedwig. 1969, 18, 383–396. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, E.E. Marine ascomycetes from New England. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1970, 97, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayarathne, M.C.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Jones, E.B.G.; Chomnunti, P.; Hyde, K.D. A novel marine genus, Halobyssothecium (Lentitheciaceae) and epitypification of Halobyssothecium obiones comb. nov. Mycol. Prog. 2018, 17, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccardo, P.A. Sylloge fungorum Omnium Hucusque Cognitorum; R. Friedländer & Sohn.: Berlin, Germany, 1883; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.B.G.; Hyde, K.D.; Boonmee, S.; Tibell, S.; Tibell, L.; Pang, K.L.; Phookamsak, R. Phylogenetic assessment and taxonomic revision of Halobyssothecium and Lentithecium (Lentitheciaceae, Pleosporales). Mycol. Prog. 2021, 20, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryckegem, G.; Aptroot, A. A new Massarina and a new Wettsteinina (Ascomycota) from freshwater and tidal reeds. Nov. Hedwig. 2001, 73, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibell, S.; Tibell, L.; Pang, K.L.; Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.B.G. Marine fungi of the Baltic Sea. Mycology 2020, 11, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.J.; Hyde, K.D.; Zhao, R.L.; Hongsanan, S.; Abdel-Aziz, F.A.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Alvarado, P.; Alves-Silva, G.; Ammirati, J.F.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 253–366: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2016, 78, 1–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.B.; Everhart, B.M. New Fungi. J. Mycol. 1885, 1, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.B.; Everhart, B.M. The North American Pyrenomycetes. A Contribution to Mycologic Botany; Ellis & Everhart: Newfield, NJ, USA, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, M.T. Culture studies on portuguese species of Leptosphaeria I. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, E.E. Fungi from a Massachusetts salt marsh. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 1966, 85, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, R.W.G. British Ascomycetes; J. Cramer: Lehre, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Poli, A.; Vizzini, A.; Prigione, V.; Varese, G.C. Basidiomycota isolated from the Mediterranean Sea—Phylogeny and putative ecological roles. Fungal Ecol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansford, C.G. Australian fungi IV. New species and revisions (cont’d). Proc. Linn. Soc. N. S. W. 1957, 82, 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K.D.; Hongsanan, S.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jones, E.B.G.; Phookamsak, R.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Boonmee, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 367–490: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2016, 80, 1–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 4. New marine ascomycetes. Mycologia 1995, 87, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 14. Three new coelomycetes, including Floricola, anam.-gen. nov. Bot. Mar. 2000, 43, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, H. Mycotheca germanica. Fasc. XX–XXI. Ann. Mycol. 1911, 9, 554–558. [Google Scholar]

- Dayarathne, M.; Jones, E.; Maharachchikumbura, S.; Devadatha, B.; Sarma, V.; Khongphinitbunjong, K.; Chomnunti, P.; Hyde, K. Morpho-molecular characterization of microfungi associated with marine based habitats. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 1–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Chaiwan, N.; Norphanphoun, C.; Boonmee, S.; Camporesi, E.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Dayarathne, M.C.; de Silva, N.I.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Ekanayaka, A.H.; et al. Mycosphere notes 169–224. Mycosphere 2018, 9, 271–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Crous, P.W.; Wijayawardene, N.N.; Jones, E.B.G.; Bhat, D.J.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Dayarathne, M.C.; et al. Phylogenetic revision of Camarosporium (Pleosporineae, Dothideomycetes) and allied genera. Stud. Mycol. 2017, 87, 207–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, W.B. British Stem- and Leaf-Fungi Vol. II; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Atrotorquata and Loratospora: New ascomycete genera on Juncus roemerianus. Syst. Ascomycetum 1993, 12, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Tsui, C.K.M. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 17. New ascomycetes and the hyphomycete genus Kolletes gen. nov. Bot. Mar. 2005, 48, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.; Moss, S.T.; Jones, E.B.G. Ascospore ultrastructure of Pleospora gaudefroyi (Pleosporaceae, Loculoascomycetes, Ascomycotina). Can. J. Bot. 1994, 72, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Lucas, M.T. Observations on British species of Pleospora. II. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1961, 44, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, B.C.; Pirozynski, K.A. Notes on British microfungi. I. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spegazzini, C. Mycetes Argentinenses. Series IV. An. del Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Buenos Aires. Ser. 3 1909, 12, 257–458. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 6. Glomerobolus gen. nov., the first ballistic member of Agonomycetales. Mycologia 1996, 88, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, S.A.; Hanlin, R.T.; Newell, S.Y. A new species of Lachnum on Spartina alterniflora. Mycotaxon 1996, 57, 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.B.; Everhart, B.M. New species of fungi from various localities. J. Mycol. 1888, 4, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Baral, H.-O.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 10. A new Orbilia with ingoldian anamorph. Mycologia 1998, 90, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaver, F.J. The North American Cup-Fungi (Inoperculates); Lancaster Press Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M.K.M.; Goh, T.K.; Hyde, K.D. A new species of Phragmitensis (ascomycetes) from senescent culms of Phragmites australis. Fungal Divers. 1999, 2, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann Kohlmeyer, B.; Eriksson, O.E. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 3. New ascomycetes. Bot. Mar. 1995, 38, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 16. More new coelomycetes, including Tetranacriella, gen. nov. Bot. Mar. 2001, 44, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Two new genera of Ascomycotina from saltmarsh Juncus. Syst. Ascomycetum 1993, 11, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Loveless, A.R.; Peach, J.M. Evidence from ascospores for host restriction in Claviceps purpurea. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1986, 86, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveless, A.R. Conidial evidence for host restriction in Claviceps purpurea. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1971, 56, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, R. Septoria disease of Gramineae in western United States. Oregon State Monogr. Stud. Bot. 1944, 6, 1–151. [Google Scholar]

- Spegazzini, C. Fungi Argentini additis nonnullis brasiliensibus montevidensibusque. An. la Soc. Cient. Argent. 1882, 13, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Peach, J.M.; Loveless, A.R. A comparison of two methods of inoculating Triticum aestivum with spore suspensions of Claviceps purpurea. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1975, 64, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleuterius, L.N.; Meyers, S.P. Claviceps purpurea on Spartina in coastal marshes. Mycologia 1974, 66, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, R. Diseases of Cereals and Grasses in North America: Fungi Except Smuts and Rusts; Ronald Press Company: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Mantle, P.G. Development of alkaloid production in vitro by a strain of Claviceps purpurea from Spartina townsendii. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1969, 52, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberley, D.G. Taxonomy and distribution of the genus Spartina. Iowa State J. Sci. 1956, 30, 471–574. [Google Scholar]

- Saccardo, P.A. Sylloge Fungorum Omnium Hucusque Cognitorum; R. Friedländer & Sohn.: Berlin, Germany, 1886; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, S.K.; Abdulkadder, M.A.; Goos, R.D. Basramyces marinus nom.nov. (hyphomycete) from southern marshes of Iraq. Int. J. Mycol. Lichenol. 1989, 4, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Pang, K.L.; Nagahama, T.; Abdel-Aziz, F.A.; Jones, E.B.G. Phylogenetic evaluation of anamorphic species of Cirrenalia and Cumulospora with the description of eight new genera and four new species. Mycol. Prog. 2010, 9, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.W. Marine Fungi. IV. Lulworthia and Ceriosporopsis. Mycologia 1958, 50, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, I.; Diehl, W.W. A new Ophiobolus on eelgrass. Can. J. Res. 1934, 11, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.W. Marine fungi. II. Ascomycetes and Deuteromycetes from submerged wood. Mycologia 1956, 48, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, L.S.; Wilson, I.M. Development of the perithecium in Lulworthia medusa (Ell. & Ev.) Cribb & Cribb, a saprophyte on Spartina townsendii. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1962, 45, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 1. Trichocladium medullare sp. nov. Mycotaxon 1995, 53, 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Kohlmeyer, J. A new Aniptodera (Ascomycotina) from saltmarsh Juncus. Bot. Mar. 1994, 37, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, R.V. Spartina alterniflora seed fungi. Can. J. Bot. 1978, 56, 2942–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. Icones Fungorum Maris. Fasc. 1–9; J. Cramer: Weinheim/Lehre, Germany, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.B.G. Haligena spartinae sp. nov., a pyrenomycete on Spartina townsendii. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1962, 45, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Bhat, D.J.; Boonmee, S.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Phookamsak, R.; Phukhamsakda, C.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 1–110: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal species. Fungal Divers. 2015, 72, 1–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, C.R. Graminicolous species of Phyllachora in North America. Mycologia 1944, 36, 18–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Octopodotus stupendus gen. & sp. nov. and Phyllachora paludicola sp. nov., two marine fungi from Spartina alterniflora. Mycologia 2003, 95, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Aropsiclus nom. nov. (Ascomycotina) to replace Sulcospora Kohlm. & Volk.-Kohlm. Syst. Ascomycetum 1994, 13, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner, B.M. New records and species of British microfungi. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1981, 76, 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayarathne, M.C.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Devadatha, B.; Abeywickrama, P.; Gareth Jones, E.B.; Chomnunti, P.; Sarma, V.V.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S.; Mckenzie, E.H.C. Modern taxonomic approaches to identifying diatrypaceous fungi from marine habitats, with a novel genus Halocryptovalsa Dayarathne & K.D.Hyde, gen. Nov. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2020, 41, 21–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.W.J.; Gold, H.S. Didymosamarospora, a new genus of fungi from fresh and marine waters. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 1957, 73, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus: New coelomycetes with notes on Dwayaangam junci. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. Fungi on Juncus roemerianus. 13. Hyphopolynema juncatile sp. nov. Mycotaxon 1999, 70, 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. Marine fungi from tropical America and Africa. Mycologia 1971, 63, 831–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. New marine fungi from mangroves and trees along eroding shorelines. Nov. Hedwig. 1965, 9, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.B.; Everhart, B.M. New species of North American fungi from various localities. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1893, 45, 128–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, G.B. The Rust Fungi of Cereals, Grasses and Bamboos; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Orton, C.R. Manual of the Rusts in United States and Canada; Purdue Research Foundation: Lafayette, IN, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- von Thümen, F. Fungi Egyptiaci, Ser. III. Flora (Regensbg.) 1880, 63, 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, D. The Smuts of Australia, Their Structure, Life History, Treatment, and Classification; Department of Agriculture of Victoria, Melbourn, Australia: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R.; Lutz, M.; Piatek, M.; Vánky, K.; Oberwinkler, F. Flamingomyces and Parvulago, new genera of marine smut fungi (Ustilaginomycotina). Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, R.W.G. Fungi of Ammophila arenaria in Europe. Rev. Biol. 1983, 12, 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Treigienė, A. Fungi associated with Ammophila arenaria in Lithuania and taxonomical notes on some species. Bot. Lith. 2011, 17, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Echeverría, S.; Hol, W.H.G.; Freitas, H.; Eason, W.R.; Cook, R. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi of Ammophila arenaria (L.) Link: Spore abundance and root colonisation in six locations of the European coast. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2008, 44, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, P.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Pointing, S.B.; Pena-Murala, R.; Hyde, K.D. Do sea grasses harbour endophytes? In Fungi in Marine Environments; Hyde, K.D., Ed.; Fungal Diversity Press: Hong Kong, China, 2002; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, D.T. Developmental morphology of Leptosphaeria discors (Saccardo and Ellis) Saccardo and Ellis. Nov. Hedwig. 1965, 9, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, S.P.; Ahearn, D.G.; Alexander, S.K.; Cook, W.L. Pichia spartinae, a dominant yeast of the Spartina salt marsh. Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 1975, 16, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.B.G.; Pang, K.L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Scholz, B.; Hyde, K.D.; Boekhout, T.; Ebel, R.; Rateb, M.E.; Henderson, L.; Sakayaroj, J.; et al. An online resource for marine fungi. Fungal Divers. 2019, 96, 347–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, D.J.; Martiny, J.B.H. Patterns of fungal diversity and composition along a salinity gradient. ISME J. 2011, 5, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeck, T.; Epstein, S. Novel eukaryotic lineages inferred from small-subunit rRNA analyses of oxygen-depleted marine environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 2657–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini-Andreote, F.; Pylro, V.S.; Baldrian, P.; Van Elsas, J.D.; Salles, J.F. Ecological succession reveals potential signatures of marine-terrestrial transition in salt marsh fungal communities. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1984–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’entremont, T.W. Saltmarsh Sediment Fungal Communities and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Sporobolus Pumilus (Roth) (Poaceae) (Spartina Patens) of the Minas Basin, Nova Scotia; Identification, Abundance and Role in Restoration. Ph.D. Thesis, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khalmuratova, I.; Kim, H.; Nam, Y.J.; Oh, Y.; Jeong, M.J.; Choi, H.R.; You, Y.H.; Choo, Y.S.; Lee, I.J.; Shin, J.H.; et al. Diversity and plant growth promoting capacity of endophytic fungi associated with halophytic plants from the west coast of Korea. Mycobiology 2015, 43, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.H.; Yoon, H.; Kang, S.M.; Shin, J.H.; Choo, Y.S.; Lee, I.J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, J.G. Fungal diversity and plant growth promotion of endophytic fungi from six halophytes in Suncheon Bay. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 22, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalmuratova, I.; Choi, D.H.; Woo, J.R.; Jeong, M.J.; Oh, Y.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, I.J.; Choo, Y.S.; Kim, J.G. Diversity and plant growth-promoting effects of fungal endophytes isolated from salt-tolerant plants. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandalepas, D.; Blum, M.J.; Van Bael, S.A. Shifts in symbiotic endophyte communities of a foundational salt marsh grass following oil exposure from the deepwater horizon oil spill. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciá-Vicente, J.G.; Jansson, H.B.; Abdullah, S.K.; Descals, E.; Salinas, J.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V. Fungal root endophytes from natural vegetation in Mediterranean environments with special reference to Fusarium spp. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 64, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.-H.; Yoon, H.-J.; Woo, J.-R.; Seo, Y.-G.; Kim, M.-A.; Lee, G.-M.; Kim, J.-G. Diversity of endophytic fungi from the roots of halophytes growing in Go-chang salt marsh. Korean J. Mycol. 2012, 40, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalmuratova, I.; Choi, D.H.; Yoon, H.J.; Yoon, T.M.; Kim, J.G. Diversity and plant growth promotion of fungal endophytes in five halophytes from the Buan salt marsh. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanasundaram, I.; Nagamuthu, J.; Muthukumaraswamy, S. Antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi isolated and identified from salt marsh plant in Vellar Estuary. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 7, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, W.H.; Marra, R.E. New species of Fusarium associated with dieback of Spartina alterniflora in Atlantic salt marshes. Mycologia 2011, 103, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alber, M.; Swenson, E.M.; Adamowicz, S.C.; Mendelssohn, I.A. Salt marsh dieback: An overview of recent events in the US. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 80, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, W.H. Pathogenic microfungi associated with Spartina in salt marshes. In Biology of Microfungi; Li, D.-W., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Cham: Switzerland, 2016; pp. 615–630. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, L.L.; in’T Veld, W.A.M.; Meffert, J.P.; Bouma, T.J.; van Rijswick, P.C.J.; Heusinkveld, J.H.T.; Orth, R.J.; van Katwijk, M.M.; van der Heide, T. Marine Phytophthora species can hamper conservation and restoration of vegetated coastal ecosystems. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20160812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, A.J.; DiTomaso, J.M.; Gordon, T.R.; Aegerter, B.J.; Ayres, D.R. Salt marsh Claviceps purpurea in native and invaded Spartina marshes in Northern California. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raybould, A.F.; Gray, A.J.; Clarke, R.T. The long-term epidemic of Claviceps purpurea on Spartina anglica in Poole Harbour: Pattern of infection, effects on seed production and the role of Fusarium Heterosporum. New Phytol. 1998, 138, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Norphanphoun, C.; Chen, J.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Doilom, M.; Hongsanan, S.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Jeewon, R.; Perera, R.H.; Thongbai, B.; et al. Thailand’s amazing diversity: Up to 96% of fungi in northern Thailand may be novel. Fungal Divers. 2018, 93, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadatha, B.; Jones, E.B.G.; Pang, K.L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Sakayaroj, J.; Bahkali, A.H.; Calabon, M.S.; Sarma, V.V.; Sutreong, S.; et al. Occurrence and geographical distribution of mangrove fungi. Fungal Divers. 2021, 106, 137–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, B.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Raja, H.A.; Tanaka, K.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Abdel-Aziz, F.A.; Doilom, M.; Phookamsak, R.; et al. Freshwater Dothideomycetes. Fungal Divers. 2020, 105, 319–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.L.; Hyde, K.D.; Liu, J.K.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Jeewon, R.; Bao, D.F.; Bhat, D.J.; Lin, C.G.; Li, W.L.; Yang, J.; et al. Freshwater Sordariomycetes. Fungal Divers. 2019, 99, 451–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Luangharn, T.; Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.B.G.; Hongsanan, S.; Lumyong, S. The rise of mycology in Asia. Sci. Asia 2020, 46, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.B.G.; Boonmee, S.; Doilom, M.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Five novel freshwater ascomycetes indicate high undiscovered diversity in lotic habitats in Thailand. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintilan, N. Biogeography of Australian saltmarsh plants. Austral Ecol. 2009, 34, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D.M.; Hickling, V.; Spencer, J.F.T. Yeasts from ponds, streams and salt marsh on the Gower Peninsula, Wales. In Advances in Biotechnology. Proceedings of the Fifth International Yeast Symposium Held in London, Canada, July 20–25; Stewart, G., Russell, I., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; pp. 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, C.P. Saturnospora ahearnii, a new salt marsh yeast from Louisiana. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1991, 60, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).