Abstract

Fungal pure cultures identified with both classical morphological methods and through barcoding sequences are a basic requirement for reliable reference sequences in public databases. Improved techniques for an accelerated DNA barcode reference library construction will result in considerably improved sequence databases covering a wider taxonomic range. Fast, cheap, and reliable methods for obtaining DNA sequences from fungal isolates are, therefore, a valuable tool for the scientific community. Direct colony PCR was already successfully established for yeasts, but has not been evaluated for a wide range of anamorphic soil fungi up to now, and a direct amplification protocol for hyphomycetes without tissue pre-treatment has not been published so far. Here, we present a colony PCR technique directly from fungal hyphae without previous DNA extraction or other prior manipulation. Seven hundred eighty-eight fungal strains from 48 genera were tested with a success rate of 86%. PCR success varied considerably: DNA of fungi belonging to the genera Cladosporium, Geomyces, Fusarium, and Mortierella could be amplified with high success. DNA of soil-borne yeasts was always successfully amplified. Absidia, Mucor, Trichoderma, and Penicillium isolates had noticeably lower PCR success.

Keywords:

soil fungi; direct PCR; barcoding; fungal isolates; yeasts; reference library construction 1. Introduction

Fungal pure cultures, identified with both classical morphological methods and through barcoding sequences are especially valuable for a reliable identification of environmental sequences and for comparative analyses, e.g., concerning the distribution and ecology of fungal taxa [1,2,3,4]. This, in turn, makes a fast, cheap, and reliable method for obtaining DNA sequences from fungal isolates a valuable tool.

Direct colony PCR is a fast technique, and is regularly applied for PCR amplification of bacterial cell cultures, cell lines, and yeast cultures. Moreover, direct colony PCR was also successfully established for other groups of organisms, e.g., Acanthamoeba [5,6], Chironomidae animals [7], fungus-like organisms, such as Oomycota [8], viruses [9], and plants [10]. Commercial direct PCR kits, e.g., for human tissue and blood, animals and plants, are already on the market. Yeasts and some other selected fungal taxa were successfully amplified with commercial direct PCR plant kits [10,11], but anamorphic soil fungi were not tested extensively for direct PCR success. As red yeasts have been shown to be problematic for direct PCR amplification, the method was optimized for them [12] and for selected human pathogenic yeasts, as well as for Aspergillus fumigatus [13]. Mutualistic Basidiomycota and Ascomycota were also successfully amplified directly from cleaned mycorrhized root tips without previous DNA extraction [14], and a direct PCR in combination with species-specific primers allowed for a fast identification of Tuber melanosporum fruiting bodies [15]. Fungal endophytes isolated from grapevines were successfully amplified directly from fungal colonies, but only after an intricate pre-treatment of the fungal tissue [16].

The main aim of the present study was to establish and test a modified direct colony PCR protocol for amplification of fungal tissue without laborious pre-treatment. Our second question was whether this direct colony PCR technique could be successfully applied to a wide range of important soil fungi. We, therefore, tested a wide taxonomic range of soil hyphomycetes and yeasts (123 species), and also tested for PCR reproducibility within species by including several isolates of one species in our tests.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 788 fungal pure cultures from the culture collection of the University Innsbruck were used for this study. Fungal cultures were isolated from soil [17,18,19] or from wood [20]. Pure cultures of 123 soil fungal taxa were deposited in the Jena Microbial Resource Collection (JMRC). A list of tested pure cultures with morphology-based identification, collection numbers, Genbank Accession numbers, and JMRC numbers are provided in Appendix Table A1. Direct colony PCR works independently of the cultivation media and of the amplified target region [10,12,15,16], but in order to allow for a meaningful comparison of PCR success, all fungal isolates were cultivated on 3% malt extract agar (MEA) and amplified with the primers ITS1F and ITS4.

2.1. Media and Cultivation

PCR amplification was carried out with fungal pure cultures cultivated on 3% MEA media without antibiotics. Pure cultures were usually incubated at 25 °C, with the exception of psychrophilic fungi, which were incubated at 10 °C.

2.2. Morphological Identification of Isolates

Morphological identification was based on growth characteristics of cultures and on morphological characters. Additional growth media, e.g., Czapek Yeast Extract Agar (CYA) and 25% Glycerol Nitrate Agar (G25N) for Penicillium [21], were used to assist with morphological identification when appropriate. The use of antibiotics in growth media was omitted to avoid changes in fungal morphology that might hamper morphological identification. The identification of fungal genera was based on general literature for soil fungi [22,23]. Whenever possible, exact species identification was carried out based on monographs on the respective genera [21,24].

2.3. Direct PCR of Fungal Cultures

Fungal tissue for amplification was taken directly from pure cultures that were about one week old. Heat-sterilized toothpicks or sterile syringe needles were used for transferring a pin point of fungal tissue directly into the already prepared and portioned PCR reaction mixture. Care was taken to transfer only minute amounts of fungal material.

The amplification of fungal rDNA-ITS-region was carried out using the primer pair ITS1F [25] and ITS4 [26]. PCR was conducted by a Primus 96 thermal cycler (VWR Life Science Competence Center, Erlangen, Germany) in a 25 µL volume reaction containing one-fold buffer S (1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM TrisHCl, 50 mM KCl), 2 mg/mL BSA, 400 nM of each primer, 200 nM for each dNTP, and 0.75 U of Taq DNA polymerase (VWR Life Science Competence Center, Erlangen, Germany). The amplification conditions were 10 min of initial denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension step of 72 °C for 7 min. (modified from [14]). 2 µL of PCR product from each reaction were mixed with 2 µL loading dye (six-fold diluted) and electrophoresed in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel with 10 μg/μL ethidium bromide. A GeneGenius Imaging system (Syngene, Cambridge, UK) with ultraviolet light was used for visualization. Clean-up and sequencing of PCR products was performed by MicroSynth AG (Balgach, Switzerland) with the primers ITS1 or ITS4.

2.4. Sequence Analysis and Data Handling

The generated rDNA ITS sequences were visualized in Sequencher (V.5.2.3; Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) followed by BLAST analyses in GenBank and UNITE. Sequences were assembled in Sequencher to form CONTIGS with a sequence homology of 99% and an overlap of 80%. Fungal cultures with ≥99% sequence identity were defined as one molecular operational taxonomic unit (MOTU). MOTUs were used because ITS regions are sometimes not reliable for morphological species delimitation. One representative sequence of each MOTU was submitted to GenBank. Sequences can be retrieved under the GenBank accession numbers KP714530–KP714713 (also listed in Appendix Table A1).

3. Results

PCR Success from Fungal Pure Cultures

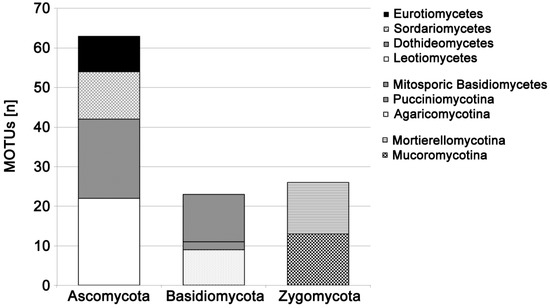

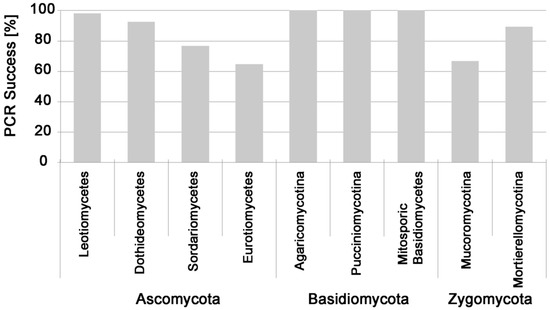

Soil fungi belonging to Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycotina, and Mucoromycotina were successfully tested (Figure 1). Direct PCR success was generally high: a total of 788 different fungal pure cultures were tested with an overall PCR success of 86%. Suitability for this direct PCR method varied between fungal groups: success was nearly 100% for soil-associated cultivable Basidiomycota, but only 67% for Mucoromycotina and 65% for Eurotiomycetes (Figure 2). This was mainly because direct PCR success of fungal cultures was characteristic for soil fungal genera: 91% of the 48 isolated genera of soil fungi had a very high (>90%, n = 41 genera) or high (>80%, n = 3 genera) PCR success, with exceptions of Absidia (0%), Mucor (58%), Penicillium (65%), and Trichoderma (36%) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Number of fungal MOTUs tested and successfully amplified with the colony PCR technique, sorted by taxonomic affiliation.

Figure 2.

Direct PCR success for pure cultures of soil fungi belonging to different fungal subphyla.

Table 1.

Relative direct PCR success for genera of soil fungi (in alphabetical order) with taxonomic affiliations, MOTUs obtained within the genus and number of fungal isolates tested.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Advantages of Direct Fungal Colony PCR

We found the direct fungal colony PCR technique presented here to be fast and easy to handle, allowing for DNA amplification directly from fungal tissue without prior manipulation or treatment; instead, the mycelium is recovered directly from culture plates or other substrates with a sterile needle or toothpick, and used for direct PCR. This method, thus, requires neither the use of expensive and specialized equipment, nor of special kits or reagents.

Our direct colony PCR technique worked for a wide range of soil hyphomycete taxa, and was also always very successful for yeasts. Compared to commercially available kits, this technique is cheaper, and can be carried out anywhere, also under circumstances where access to commercial kits is difficult or too expensive. In addition, we suggest that this technique may be a valuable tool for teaching courses, where the robustness of techniques used as well as time and money are of immediate concern.

The main advantage of this direct fungal colony PCR method compared to established direct PCR protocols for fungi is that it does not require time-consuming previous tissue manipulation or the use of expensive reagents such as proteinase K or other enzymes. The only additional reagent used for direct fungal colony PCR is bovine serum albumin (BSA). However, pre-treatment of fungal tissue, as earlier described by Pancher et al. [16], is still the most promising strategy for fungal colonies belonging to genera that could not be successfully (or at least reliably) amplified by direct fungal colony PCR, e.g., Trichoderma or Absidia spp. For this pre-treatment, fresh mycelium and the agar medium underneath are frozen at −80 °C and lysed mechanically. Then, sterile distilled water is added to the lysate, which is then mixed and centrifuged. Finally, the supernatant is used as a template [16]. Alternatively, fungal tissue could also be pre-treated with heat, buffers, microwave, and enzymes [12].

The direct colony PCR method discussed here proved very suitable to obtain sequences from a wide range of soil hyphomycete isolates belonging to different phylogenetic lineages (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Zygomycota), among them important and widespread genera of saprobial soil fungi like Geomyces/Pseudogymnoascus, Cladosporium, and Mortierella. The very high overall PCR success obtained in this study suggests broad applicability for this fast, cheap, and reliable technique. This direct PCR technique was established based on the excellent results obtained by direct PCR of ectomycorrhizal tissues [14,17] and was also successfully applied on pure cultures of a range of agaricoid and polyporous fungi [20]. This suggests that this PCR method would also work for other fungal groups, which were not included in the test e.g., food-borne fungi or plant-pathogenic fungi.

4.2. Factors Affecting Direct Colony PCR Success

Taxonomic affiliation affects direct colony PCR success: The direct PCR technique can be recommended for a cheap, high-throughput amplification technique for fungal cultures covering a wide taxonomic range, because overall PCR success was very high (86%). However, direct colony PCR success varied between genera of hyphomycetes. Most of the tested genera of soil-borne hyphomycetes like Cladosporium, Geomyces, Fusarium, and Mortierella could be amplified with high success, and soil-borne yeasts were always successfully amplified. Other fungal growth forms like coelomycetous or as sterile mycelia also appear to be very suitable for direct colony PCR. Mucor, Trichoderma, and Penicillium had noticeably lower PCR success in comparison with other fungal groups that were repeatedly tested, and DNA could not be amplified from Absidia isolates (seven different isolates, all repeatedly tested). A pre-treatment of fungal tissue or spores, e.g., as described by Pancher et al. [16] seems to be necessary for successful direct colony PCR of these fungal genera.

Failed PCR reactions could also be caused by excessive amounts of fungal template material added to the PCR master mix [14]. Transferring only miniscule amounts of fungal tissue into the reaction mixture is critical for success, but can prove challenging when working with isolates that show excessive sporulation (e.g., Penicillium) and/or extremely fast growth (Mucor and Absidia).

DNA template quality is usually good for fungal samples obtained from the growing edge of fungal colonies: DNA is neither fragmented nor degraded. However, DNA purity can be an important issue for PCR success, as shown for plants [27]. Polysaccharides and pigments impair DNA purity, and have been described as an important issue in PCR amplification of Trichoderma [28]. In these cases, DNA extraction and DNA purification are therefore essential steps for a successful PCR amplification.

Finally, primer choice can sometimes be crucial for PCR success [29], and potential primer bias is an issue also for fungi [30]. Multiple direct colony PCRs with different primer combinations or specific primers [31,32,33,34,35] could be carried out to solve this problem.

4.3. Potential Applications for Direct Fungal Colony PCR

This fast and cheap direct fungal colony PCR method can be used for many other applications apart from obtaining barcoding sequences from pure culture collections. Direct colony PCR products can also be used for cloning and thus allow e.g. for a direct amplification of fungi from the environment without prior cultivation. The use of other primers and primer combinations enables for a fast and easy amplification of other target genes. Direct fungal colony PCR also allows for a reliable screening of fungal isolates, e.g. for mutant strains. A faster and cheaper method for PCR amplification of fungal environmental isolates will also contribute to a better knowledge concerning the ecology and biogeography of fungi, and to the discovery of potentially novel fungal taxa.

5. Conclusions

Direct fungal colony PCR is a fast and reliable method for crude mycelium-based amplification of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region of the fungal ribosomal DNA cluster. PCR success rate is generally high. A broad application of this method should lead to a simplification of molecular taxonomic analyses, and will allow for more extensive, sequence-based analyses of fungal environmental isolates. Improved techniques for an accelerated DNA barcode reference library construction will result in considerably improved sequence databases covering a wider taxonomic range. Fast, cheap, and reliable methods for obtaining DNA sequences from fungal isolates are, therefore, a valuable tool for the scientific community.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project “Growth response of Pinus cembra to experimentally modified soil temperatures at the treeline” (Project No. P22836-B16), and by the Tiroler Wissenschaftsfond project (TWF P718017) “How to open a Treasure Box: Barcoding of the Mycological Collection IB”. We thank the Jena Microbial Resource Collection for deposition of cultures and Philipp Dresch for assistance in the laboratory.

Author Contributions

Ursula Peintner conceived and designed the experiments; Georg Walch, Georg Rainer and Maria Knapp performed the experiments and analysed the data; Ursula Peintner and Georg Walch wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| CYA | Czapek yeast extract agar |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| G25N | 25% glycerol nitrate agar |

| ITS | internal transcribed spacer |

| JMRC | Jena Microbial Resource Collection |

| MEA | malt extract agar |

| MOTU | molecular operational taxonomic unit |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

Appendix

Table A1.

List of MOTUs obtained with direct colony PCR from 788 fungal strains. GenBank accession numbers (ACCN) and collection numbers in the Jena Microbial Resource Collection (JMRC:SF:Nr) are provided. MOTUs are sorted alphabetically by description.

| MOTU ID | MOTU Description | GenBank ACCN | JMRC:SF:Nr |

|---|---|---|---|

| MK_42 | Aureobasidium sp. | KP714635 | JMRC:SF:12047 |

| GW_52 | Bjerkandera adusta | KP714580 | JMRC:SF:12006 |

| GW_54 | Botrytis sp. | KP714582 | JMRC:SF:12008 |

| GW_07 | Cladosporium sp. 1 | KP714536 | JMRC:SF:11967 |

| GW_17 | Cladosporium sp. 2 | KP714546 | JMRC:SF:11977 |

| GW_43 | Cladosporium sp. 3 | KP714571 | JMRC:SF:12000 |

| GW_59 | Cladosporium sp. 4 | KP714587 | JMRC:SF:12012 |

| MK_40 | Cladosporium sp. 5 | KP714642 | JMRC:SF:12052 |

| GW_40 | Cryptococcus aff. albidosimilis | KP714568 | JMRC:SF:11998 |

| GW_58 | Cryptococcus aff. victoriae | KP714586 | - |

| MK_35 | Cryptococcus friedmannii | KP714628 | JMRC:SF:12041 |

| GW_18 | Cryptococcus sp. 1 | KP714547 | JMRC:SF:11978 |

| GW_24 | Cryptococcus sp. 2 | KP714553 | JMRC:SF:11984 |

| GW_33 | Cryptococcus sp. 3 | KP714562 | JMRC:SF:11992 |

| GW_36 | Cryptococcus sp. 4 | KP714565 | JMRC:SF:11995 |

| MK_45 | Cryptococcus sp. 5 | KP714638 | JMRC:SF:12048 |

| MK_72 | Cryptococcus sp. 6 | KP714662 | JMRC:SF:12074 |

| GW_19 | Cryptococcus terricola | KP714548 | JMRC:SF:11979 |

| MK_53 | Cryptococcus victoriae | KP714646 | JMRC:SF:12056 |

| MK_75 | Cystofilobasidium infirmominiatum | KP714665 | JMRC:SF:12077 |

| MK_14 | Davidiella sp. 1 | KP714607 | JMRC:SF:12027 |

| MK_70 | Davidiella sp. 2 | KP714660 | JMRC:SF:12072 |

| MK_10 | Dioszegia sp. 1 | KP714603 | JMRC:SF:12024 |

| MK_57 | Dioszegia sp. 2 | KP714649 | JMRC:SF:12060 |

| GW_48 | Dothideomycetes unknown | KP714576 | JMRC:SF:12003 |

| GW_35 | Drechslera sp. | KP714564 | JMRC:SF:11994 |

| GW_63 | Epicoccum sp. | KP714591 | JMRC:SF:12016 |

| GW_09 | Fusarium sp. 1 | KP714538 | JMRC:SF:11969 |

| MK_24 | Fusarium sp. 2 | KP714617 | JMRC:SF:12032 |

| MK_06 | Geomyces aff. vinaceus | KP714599 | JMRC:SF:12022 |

| MK_05 | Geomyces pannorum 1 | KP714598 | JMRC:SF:12021 |

| MK_20 | Geomyces pannorum 2 | KP714613 | JMRC:SF:12030 |

| GW_02 | Geomyces sp. 1 | KP714531 | JMRC:SF:11962 |

| GW_03 | Geomyces sp. 2 | KP714532 | JMRC:SF:11963 |

| GW_53 | Geomyces sp. 3 | KP714581 | JMRC:SF:12007 |

| MK_61 | Geomyces sp. 4 | KP714653 | JMRC:SF:12064 |

| MK_38 | Guehomyces pullulans | KP714631 | JMRC:SF:12043 |

| GW_46 | Helgardia sp. | KP714574 | JMRC:SF:12001 |

| MK_09 | Helotiales unknown 1 | KP714602 | JMRC:SF:12023 |

| MK_39 | Helotiales unknown 2 | KP714632 | JMRC:SF:12044 |

| GW_42 | Herpotrichia juniperi 1 | KP714570 | - |

| MK_32 | Herpotrichia juniperi 2 | KP714625 | JMRC:SF:12038 |

| MK_46 | Herpotrichia juniperi 3 | KP714639 | JMRC:SF:12049 |

| GW_39 | Hormonema sp. | KP714567 | JMRC:SF:11997 |

| GW_65 | Ilyonectria sp. | KP714593 | JMRC:SF:12018 |

| MK_63 | Leptodontidium orchidicola | KP714654 | JMRC:SF:12066 |

| MK_01 | Leucosporidiella sp. | KP714594 | JMRC:SF:12019 |

| GW_34 | Leucosporidium sp. | KP714563 | JMRC:SF:11993 |

| GW_12 | Monographella aff. lycopodina | KP714541 | JMRC:SF:11972 |

| GW_50 | Monographella sp. | KP714578 | JMRC:SF:12005 |

| GW_13 | Mortierella aff. gamsii | KP714542 | JMRC:SF:11973 |

| MK_29 | Mortierella alpina 1 | KP714622 | JMRC:SF:12035 |

| MK_34 | Mortierella alpina 2 | KP714627 | JMRC:SF:12040 |

| MK_77 | Mortierella alpina 3 | KP714667 | JMRC:SF:12079 |

| MK_52 | Mortierella antarctica | KP714645 | JMRC:SF:12055 |

| MK_50 | Mortierella globulifera 1 | KP714643 | JMRC:SF:12053 |

| MK_54 | Mortierella globulifera 2 | KP714647 | JMRC:SF:12057 |

| GW_08 | Mortierella humilis | KP714537 | JMRC:SF:11968 |

| GW_29 | Mortierella macrocystis | KP714558 | JMRC:SF:11988 |

| GW_01 | Mortierella sp. 1 | KP714530 | JMRC:SF:11961 |

| GW_16 | Mortierella sp. 2 | KP714545 | JMRC:SF:11976 |

| GW_20 | Mortierella sp. 3 | KP714549 | JMRC:SF:11980 |

| GW_27 | Mortierella sp. 4 | KP714556 | - |

| MK_31 | Mrakia blollopsis | KP714624 | JMRC:SF:12037 |

| MK_41 | Mrakia sp. | KP714634 | JMRC:SF:12046 |

| MK_25 | Mrakiella aquatica | KP714618 | JMRC:SF:12033 |

| GW_44 | Mucor aff. abundans | KP714572 | - |

| GW_45 | Mucor flavus | KP714573 | - |

| GW_15 | Mucor hiemalis 1 | KP714544 | JMRC:SF:11975 |

| MK_15 | Mucor hiemalis 2 | KP714608 | JMRC:SF:12028 |

| MK_69 | Mucor hiemalis 3 | KP714659 | JMRC:SF:12071 |

| GW_47 | Mucor strictus | KP714575 | JMRC:SF:12002 |

| MK_27 | Nectriaceae unknown | KP714620 | JMRC:SF:12034 |

| GW_55 | Penicillium aff. brevicompactum | KP714583 | JMRC:SF:12009 |

| GW_14 | Penicillium aff. lividum | KP714543 | JMRC:SF:11974 |

| GW_31 | Penicillium aff. melinii | KP714560 | JMRC:SF:11990 |

| GW_10 | Penicillium aff. spinulosum | KP714539 | JMRC:SF:11970 |

| GW_25 | Penicillium aff. ubiquetum | KP714554 | JMRC:SF:11985 |

| GW_04 | Penicillium sp. 1 | KP714533 | JMRC:SF:11964 |

| GW_23 | Penicillium sp. 2 | KP714552 | JMRC:SF:11983 |

| GW_32 | Penicillium sp. 3 | KP714561 | JMRC:SF:11991 |

| GW_49 | Penicillium sp. 4 | KP714577 | JMRC:SF:12004 |

| GW_64 | Penicillium sp. 5 | KP714592 | JMRC:SF:12017 |

| MK_60 | Penicillium sp. 6 | KP714652 | JMRC:SF:12063 |

| GW_06 | Phacidium aff. pseudophacidioides | KP714535 | JMRC:SF:11966 |

| GW_05 | Phacidium aff. trichophori | KP714534 | JMRC:SF:11965 |

| GW_41 | Phaeosphaeria sp. | KP714569 | JMRC:SF:11999 |

| GW_56 | Pleosporales unknown 1 | KP714584 | JMRC:SF:12010 |

| MK_13 | Pleosporales unknown 2 | KP714606 | JMRC:SF:12026 |

| MK_36 | Pleosporales unknown 3 | KP714629 | JMRC:SF:12042 |

| MK_47 | Pleosporales unknown 4 | KP714640 | JMRC:SF:12050 |

| MK_30 | Pseudeurotiaceae sp. | KP714623 | JMRC:SF:12036 |

| MK_40 | Pseudogymnoascus destructans 1 | KP714633 | JMRC:SF:12045 |

| MK_51 | Pseudogymnoascus destructans 2 | KP714644 | JMRC:SF:12054 |

| MK_56 | Pseudogymnoascus destructans 3 | KP714648 | JMRC:SF:12059 |

| MK_33 | Rhodotorula colostri | KP714626 | JMRC:SF:12039 |

| GW_26 | Rhodotorula sp. | KP714555 | JMRC:SF:11986 |

| GW_51 | Stemphylium sp. | KP714579 | - |

| GW_57 | Stereum sanguinolentum | KP714585 | JMRC:SF:12011 |

| MK_21 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 1 | KP714614 | JMRC:SF:12031 |

| MK_59 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 2 | KP714651 | JMRC:SF:12062 |

| MK_65 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 3 | KP714655 | JMRC:SF:12067 |

| MK_66 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 4 | KP714656 | JMRC:SF:12068 |

| MK_73 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 5 | KP714663 | JMRC:SF:12075 |

| MK_74 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 6 | KP714664 | JMRC:SF:12076 |

| MK_76 | Sterile Mycelium (Ascomycete) 7 | KP714666 | JMRC:SF:12078 |

| MK_48 | Sterile Mycelium (Basidiomycete) 1 | KP714641 | JMRC:SF:12051 |

| MK_67 | Sterile Mycelium (Basidiomycete) 2 | KP714657 | JMRC:SF:12069 |

| MK_68 | Sterile Mycelium (Basidiomycete) 3 | KP714658 | JMRC:SF:12070 |

| MK_03 | Tetracladium sp. 1 | KP714596 | JMRC:SF:12020 |

| MK_17 | Tetracladium sp. 2 | KP714610 | JMRC:SF:12029 |

| MK_71 | Tetracladium sp. 3 | KP714661 | JMRC:SF:12073 |

| MK_58 | Thelebolus sp. | KP714650 | JMRC:SF:12061 |

| GW_22 | Trichoderma sp. 1 | KP714551 | JMRC:SF:11982 |

| GW_62 | Trichoderma sp. 2 | KP714590 | JMRC:SF:11996 |

| GW_38 | Trichoderma sp. 3 | KP714566 | JMRC:SF:12015 |

| MK_12 | Truncatella angustata | KP714605 | JMRC:SF:12025 |

| GW_11 | Umbelopsis sp. 1 | KP714540 | JMRC:SF:11971 |

| GW_21 | Umbelopsis sp. 2 | KP714550 | JMRC:SF:11981 |

| GW_28 | Umbelopsis sp. 3 | KP714557 | JMRC:SF:11987 |

| GW_30 | Umbelopsis sp. 4 | KP714559 | JMRC:SF:11989 |

| GW_60 | Umbelopsis sp. 5 | KP714588 | JMRC:SF:12013 |

| GW_61 | Umbelopsis sp. 6 | KP714589 | JMRC:SF:12014 |

References

- Schadt, C.W.; Martin, A.P.; Lipson, D.A.; Schmidt, S.K. Seasonal dynamics of previously unknown fungal lineages in tundra soils. Science 2003, 301, 1359–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganley, R.J.; Brunsfeld, S.J.; Newcombe, G. A community of unknown, endophytic fungi in western white pine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10107–10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarenkov, K.; Henrik Nilsson, R.; Larsson, K.-H.; Alexander, I.J.; Eberhardt, U.; Erland, S.; Høiland, K.; Kjøller, R.; Larsson, E.; Pennanen, T.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi—Recent updates and future perspectives. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, N.M.; Younis, M.S.; Elhamshary, A.M.; Abd-Elmaboud, A.I.; Kishik, S.M. Acanthamoeba DNA can be directly amplified from corneal scrapings. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 3267–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Zhai, H.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, S.; Liu, T.; Xie, L. Rapid and sensitive diagnosis of fungal keratitis with direct PCR without template DNA extraction. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, O776–O782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.H.; Tay, Y.C.; Puniamoorthy, J.; Balke, M.; Cranston, P.S.; Meier, R. “Direct PCR” optimization yields a rapid, cost-effective, nondestructive and efficient method for obtaining DNA barcodes without DNA extraction. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014, 14, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calmin, G.; Belbahri, L.; Lefort, F. Direct PCR for DNA barcoding in the genera Phytophopthora and Pythium. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2007, 21, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urayama, S.-I.; Katoh, Y.; Fukuhara, T.; Arie, T.; Moriyama, H.; Teraoka, T. Rapid detection of Magnaporthe oryzae chrysovirus 1-A from fungal colonies on agar plates and lesions of rice blast. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2015, 81, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, P.; Chum, P.Y. Thermo Scientific Phire Plant Direct PCR Kit: Plant genotyping and transgene detection without DNA purification. In Application Note; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Vantaa, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dudaite, N.; Navickaite, M.; Dinarina, A. Direct PCR from yeast cells. In Application Note; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Vantaa, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Z.K. Highly-efficient colony PCR method for red yeasts and its application to identify mutations within two leucine auxotroph mutants. Yeast 2012, 29, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Mitchell, T.G. Rapid identification of pathogenic fungi directly from cultures by using multiplex PCR. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2860–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotti, M.; Zambonelli, A. A quick and precise technique for identifying ectomycorrhizas by PCR. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonito, G. Fast DNA-based identification of the black truffle Tuber melanosporum with direct PCR and species-specific primers. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 301, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancher, M.; Ceol, M.; Corneo, P.E.; Longa, C.M.O.; Yousaf, S.; Pertot, I.; Campisano, A. Fungal endophytic communities in grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.) respond to crop management. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4308–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainer, G.; Kuhnert, R.; Unterholzer, M.; Dresch, P.; Gruber, A.; Peintner, U. Host-specialist dominated ectomycorrhizal communities of Pinus cembra are not affected by temperature manipulation. J. Fungi 2015, 1, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, M. Fungal Communities in snow-covered alpine soil: A comparison between molecular and cultivation-based techniques. Master’s Thesis, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert, R.; Oberkofler, I.; Peintner, U. Fungal growth and biomass development is boosted by plants in snow-covered soil. Microbial. Ecol. 2012, 64, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresch, P.; D’Aguanno, M.; Rosam, K.; Grienke, U.; Rollinger, J.; Peintner, U. Fungal strain matters: Colony growth and bioactivity of the European medicinal polypores Fomes fomentarius, Fomitopsis pinicola and Piptoporus betulinus. AMB Express 2015, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.I. A Laboratory Guide to Common Penicillium Species; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Division of Food Research: North Ryde, NSW, Australia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W.; Anderson, T.H. Compendium of Soil Fungi; IHW-Verlag: Eching, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, K.; Morgan-Jones, G.; Gams, W.; Kendrick, B. The Genera of Hyphomycetes; CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bensch, K.; Braun, U.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The genus Cladosporium. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 72, 1–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Michael, A.I., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Dong, W.; Shi, S.; Cheng, T.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, P.; Wu, H.; Gao, P.; Zhou, S. Accelerating plant DNA barcode reference library construction using herbarium specimens: Improved experimental techniques. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Angulo, J.C.; Mendez-Trujillo, V.; Gonzalez-Mendoza, D.; Morales-Trejo, A.; Grimaldo-Juarez, O.; Cervantes-Diaz, L. A rapid and inexpensive method for isolation of total DNA from Trichoderma spp. (Hypocreaceae). Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A. Improved selection of internal transcribed spacer-specific primers enables quantitative, ultra-high-throughput profiling of fungal communities. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2013, 79, 2519–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellemain, E.; Carlsen, T.; Brochmann, C.; Coissac, E.; Taberlet, P.; Kauserud, H. ITS as an environmental DNA barcode for fungi: An in silico approach reveals potential PCR biases. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, X.-R.; Blomquist, G. Evaluation of PCR primers and PCR conditions for specific detection of common airborne fungi. J. Environ. Monit. 2002, 4, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolcheva, L.G.; Bärlocher, F. Taxon-specific fungal primers reveal unexpectedly high diversity during leaf decomposition in a stream. Mycol. Prog. 2004, 3, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagn, A.; Wallisch, S.; Radl, V.; Charles Munch, J.; Schloter, M. A new cultivation independent approach to detect and monitor common Trichoderma species in soils. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2007, 69, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-N.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zheng, R.-Y. Umbelopsis changbaiensis sp. nov. from China and the typification of Mortierella vinacea. Mycol. Prog. 2014, 13, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, K.; Cigelnik, E.; O’Donnell, K. Phylogeny and PCR identification of clinically important zygomycetes based on nuclear ribosomal-DNA sequence data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 3957–3964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).