Comparative Mitogenomics Reveals Intron Dynamics and Mitochondrial Gene Expression Shifts in Domesticated and Wild Pleurotus ostreatus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Nucleic Acid Extractions, Sequencing and Assembly of Mitochondrial Genome

2.3. Gene Annotation and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Analysis of Gene Expression

2.5. Data Availability

3. Results

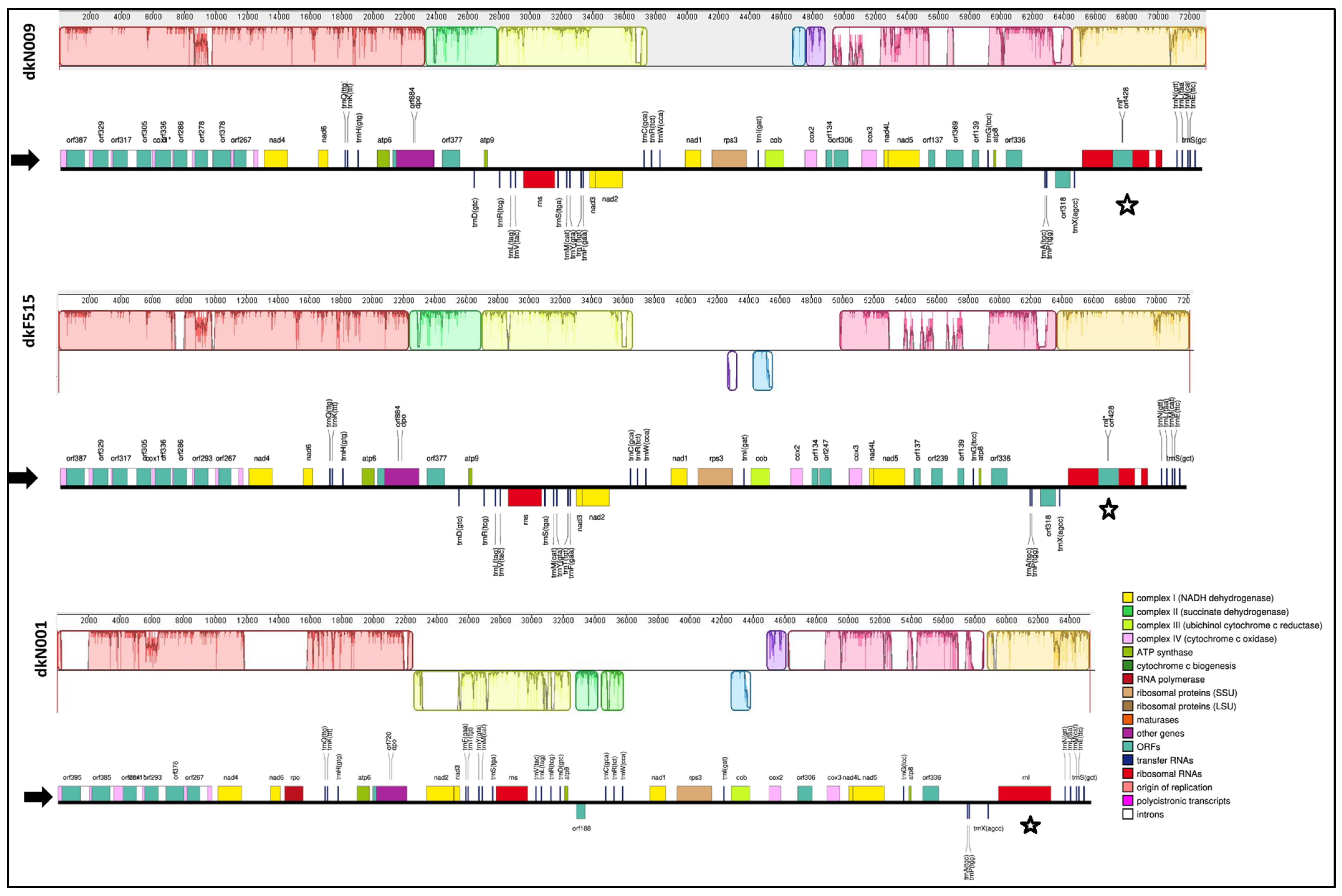

3.1. Mitochondrial Genome Overview of P. ostreatus dkN001, dkN009 and dkF515 Strains

3.2. Repetitive Elements in P. ostreatus Mitogenomes

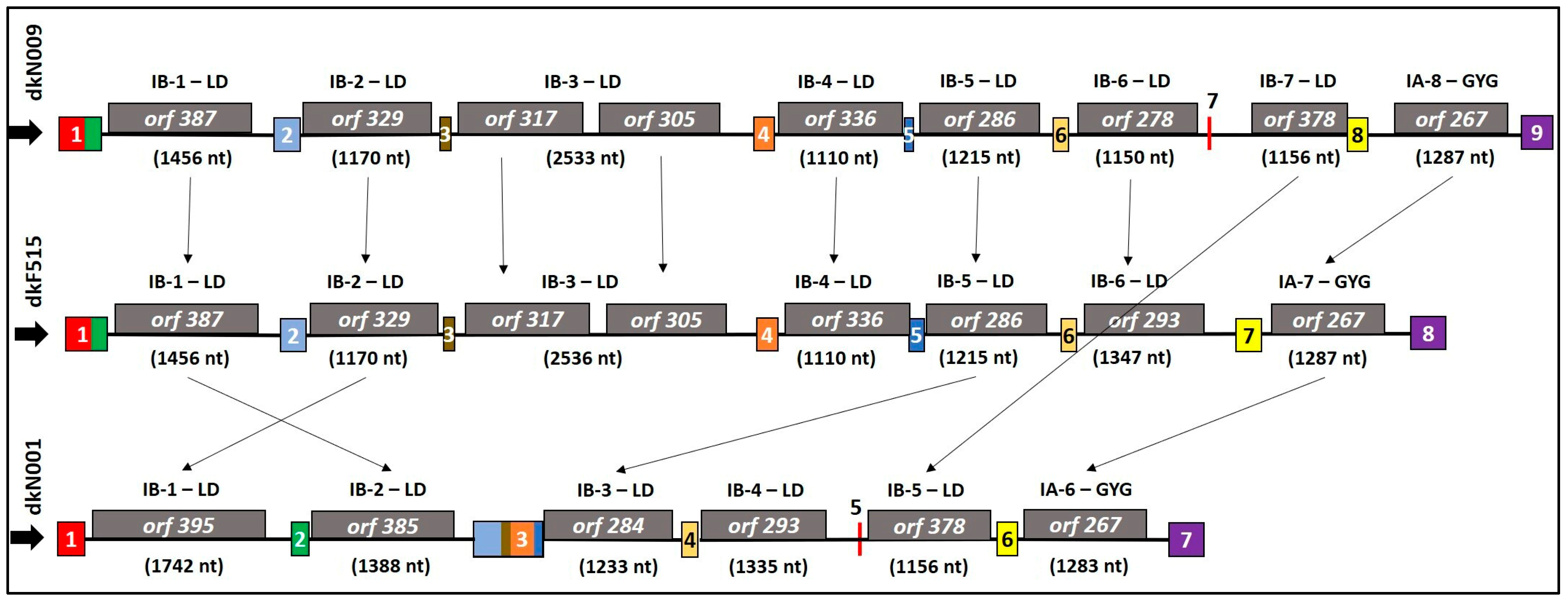

3.3. Dynamics of Introns and Intronic ORFs in cox1 and rnl Genes of P. ostreatus Strains

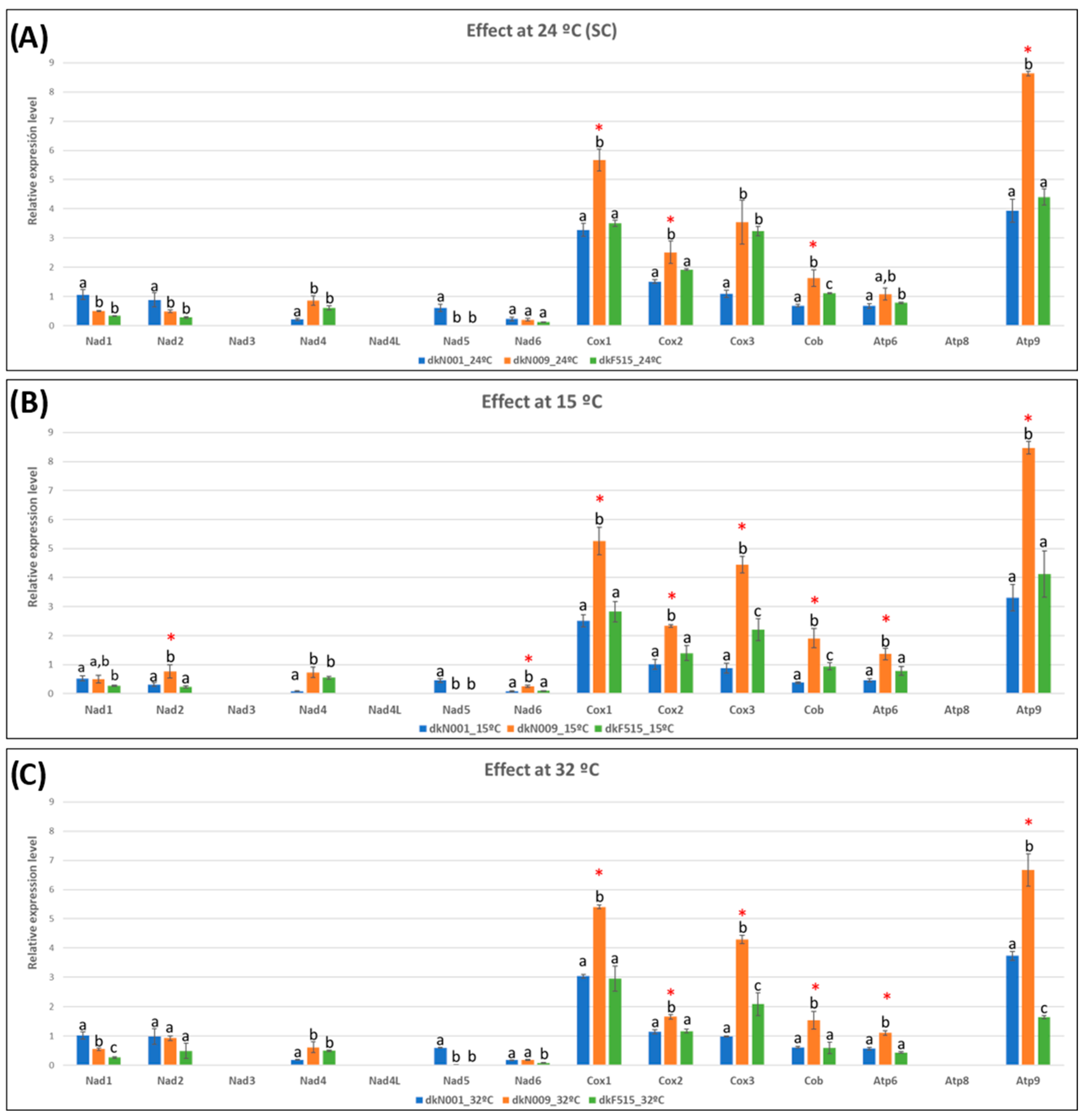

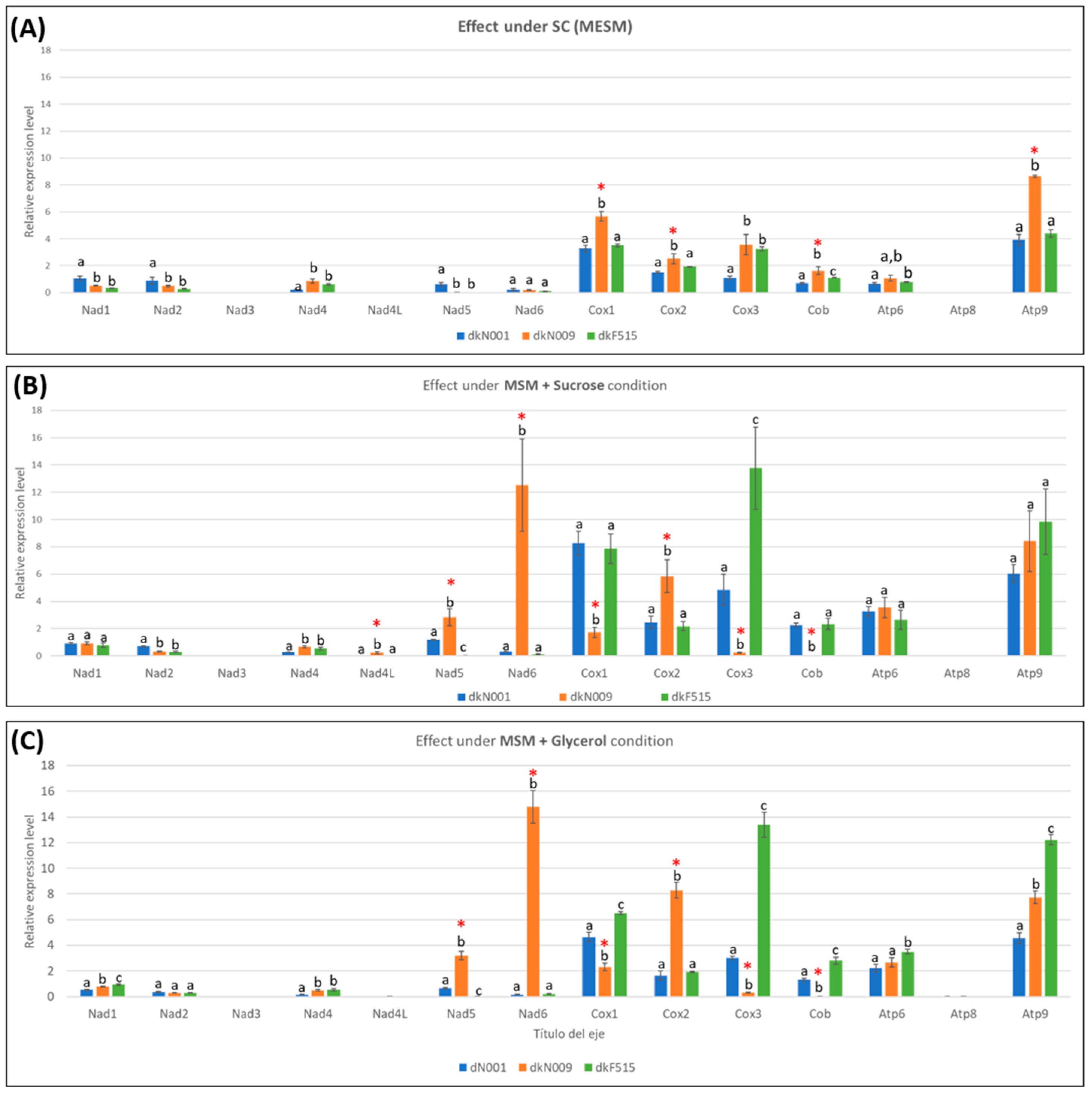

3.4. Effects of Environmental Stressors on Growth and Mitochondrial Gene Expression

3.4.1. Temperature Effects on Growth Rate and Mitochondrial Gene Transcription Levels

3.4.2. Carbon Sources Effects on Growth Rate and Mitochondrial Gene Transcription Levels

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osellame, L.D.; Blacker, T.S.; Duchen, M.R. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Function. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulik, T.; Van Diepeningen, A.D.; Hausner, G. Editorial: The Significance of Mitogenomics in Mycology. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 628579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurland, C.G.; Andersson, S.G.E. Origin and Evolution of the Mitochondrial Proteome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyton, R.O.; McEwen, J.E. Crosstalk Between Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 563–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, H.; Österman-Udd, J.; Mali, T.; Lundell, T. Basidiomycota Fungi and ROS: Genomic Perspective on Key Enzymes Involved in Generation and Mitigation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 837605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, Å.; Stenlid, J. Mitochondrial Control of Fungal Hybrid Virulence. Nature 2001, 411, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Mi, F.; Wang, R.; Mo, M.; Xu, J. Evidence for Persistent Heteroplasmy and Ancient Recombination in the Mitochondrial Genomes of the Edible Yellow Chanterelles from Southwestern China and Europe. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 699598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Shakya, V.P.S.; Idnurm, A. Exploring and Exploiting the Connection between Mitochondria and the Virulence of Human Pathogenic Fungi. Virulence 2018, 9, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavín, J.L.; Oguiza, J.A.; Ramírez, L.; Pisabarro, A.G. Comparative Genomics of the Oxidative Phosphorylation System in Fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008, 45, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malina, C.; Larsson, C.; Nielsen, J. Yeast Mitochondria: An Overview of Mitochondrial Biology and the Potential of Mitochondrial Systems Biology. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18, foy040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, L.; Xiang, D.; Wan, Y.; Wu, Q.; Huang, W.; Zhao, G. The Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Two Model Ectomycorrhizal Fungi (Laccaria): Features, Intron Dynamics and Phylogenetic Implications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, C.; Xiong, C.; Jin, X.; Chen, Z.; Huang, W. Comparative Mitogenomics Reveals Large-Scale Gene Rearrangements in the Mitochondrial Genome of Two Pleurotus Species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6143–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megarioti, A.H.; Kouvelis, V.N. The Coevolution of Fungal Mitochondrial Introns and Their Homing Endonucleases (GIY-YIG and LAGLIDADG). Genome Biol. Evol. 2020, 12, 1337–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Férandon, C.; Moukha, S.; Callac, P.; Benedetto, J.-P.; Castroviejo, M.; Barroso, G. The Agaricus bisporus Cox1 Gene: The Longest Mitochondrial Gene and the Largest Reservoir of Mitochondrial Group I Introns. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.-Y.; Deng, Y.-J.; Mukhtar, I.; Meng, G.-L.; Song, Y.-J.; Cheng, B.; Hao, J.-B.; Wu, X.-P. Mitochondrial Genome and Diverse Inheritance Patterns in Pleurotus pulmonarius. J. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jia, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, H.; Chen, M.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, N. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Medicinal Fungus Taiwanofungus camphoratus Reveals Gene Rearrangements and Intron Dynamics of Polyporales. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmay, Z.; Gorems, W.; Birhanu, G.; Zewdie, S. Growth and Yield Performance of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq. Fr.) Kumm (Oyster Mushroom) on Different Substrates. AMB Express 2016, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viriato, V.; Mäkelä, M.R.; Kowalczyk, J.E.; Ballarin, C.S.; Loiola, P.P.; Andrade, M.C.N. Organic Residues from Agricultural and Forest Companies in Brazil as Useful Substrates for Cultivation of the Edible Mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 74, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Kawauchi, M.; Otsuka, Y.; Han, J.; Koshi, D.; Schiphof, K.; Ramírez, L.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Honda, Y. Pleurotus ostreatus as a Model Mushroom in Genetics, Cell Biology, and Material Sciences. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafforov, Y.; Yamaç, M.; İnci, Ş.; Rapior, S.; Yarasheva, M.; Rašeta, M. Pleurotus Eryngii (DC.) Quél.; Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm.-PLEUROTACEAE. In Ethnobiology of Uzbekistan: Ethnomedicinal Knowledge of Mountain Communities; Khojimatov, O.K., Gafforov, Y., Bussmann, R.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1335–1388. ISBN 978-3-031-23031-8. [Google Scholar]

- Krupodorova, T.; Barshteyn, V.; Tsygankova, V.; Sevindik, M.; Blume, Y. Strain-Specific Features of Pleurotus ostreatus Growth in Vitro and Some of Its Biological Activities. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraya, L.; Peñas, M.M.; Pérez, G.; Santos, C.; Ritter, E.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Ramírez, L. Identification of Incompatibility Alleles and Characterisation of Molecular Markers Genetically Linked to the A Incompatibility Locus in the White Rot Fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Curr. Genet. 1999, 34, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larraya, L.M.; Pérez, G.; Iribarren, I.; Blanco, J.A.; Alfonso, M.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Ramírez, L. Relationship between Monokaryotic Growth Rate and Mating Type in the Edible Basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3385–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Chuina, E.; Ibañez-Vea, M.; Garde, E.; López-Llorca, L.V.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Ramírez, L. Strain Degeneration in Pleurotus ostreatus: A Genotype Dependent Oxidative Stress Process Which Triggers Oxidative Stress, Cellular Detoxifying and Cell Wall Reshaping Genes. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garde, E.; Pérez, G.; Jiménez, I.; Calvo, M.I.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Ramírez, L. Asymmetric Mitonuclear Interactions Trigger Transgressive Inheritance and Mitochondria-Dependent Heterosis in Hybrids of the Model System Pleurotus ostreatus. IMA Fungus 2025, 16, e165520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.F.; Latorre-Muro, P.; Puigserver, P. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Respiratory Adaptation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, M.R.; Thorgaard, G.H.; Narum, S.R. Differential Expression of Genes That Control Respiration Contribute to Thermal Adaptation in Redband Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri). Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhan, L.; Storey, K.B.; Zhang, J.; Yu, D. Differential Mitochondrial Genome Expression of Four Skink Species Under High-Temperature Stress and Selection Pressure Analyses in Scincidae. Animals 2025, 15, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Ming, C.; Li, Y.; Su, L.-Y.; Su, Y.-H.; Otecko, N.O.; Liu, H.-Q.; Wang, M.-S.; Yao, Y.-G.; Li, H.-P.; et al. Rapid Evolution of Genes Involved in Learning and Energy Metabolism for Domestication of the Laboratory Rat. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3148–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, C.; Bachmann, L.; Chevreux, B. Reconstructing Mitochondrial Genomes Directly from Genomic Next-Generation Sequencing Reads—A Baiting and Iterative Mapping Approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, B.F.; Beck, N.; Prince, S.; Sarrasin, M.; Rioux, P.; Burger, G. Mitochondrial Genome Annotation with MFannot: A Critical Analysis of Gene Identification and Gene Model Prediction. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1222186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Externbrink, F.; Florentz, C.; Fritzsch, G.; Pütz, J.; Middendorf, M.; Stadler, P.F. MITOS: Improved de Novo Metazoan Mitochondrial Genome Annotation. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Höner zu Siederdissen, C.; Tafer, H.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2011, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) Version 1.3.1: Expanded Toolkit for the Graphical Visualization of Organellar Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.C.E.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple Alignment of Conserved Genomic Sequence with Rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, G. Tandem Repeats Finder: A Program to Analyze DNA Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisano, H.; Tsujimura, M.; Yoshida, H.; Terachi, T.; Sato, K. Mitochondrial Genome Sequences from Wild and Cultivated Barley (Hordeum vulgare). BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-C.; Xie, T.-C.; Feng, X.-L.; Wang, Z.-X.; Lin, C.; Li, G.-M.; Li, X.-Z.; Qi, J. The First Five Mitochondrial Genomes for the Family Nidulariaceae Reveal Novel Gene Rearrangements, Intron Dynamics, and Phylogeny of Agaricales. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohany, O.; Gentles, A.J.; Hankus, L.; Jurka, J. Annotation, Submission and Screening of Repetitive Elements in Repbase: Repbase Submitter and Censor. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Kojima, K.K.; Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a Database of Repetitive Elements in Eukaryotic Genomes. Mob. DNA 2015, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, F.; Hon, C.C.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, F.C.C. The Mitochondrial Genome of the Basidiomycete Fungus Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster Mushroom). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 280, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Edible Mushroom Pleurotus giganteus (Agaricales, Pleurotus) and Insights into Its Phylogeny. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2022, 7, 1313–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Z.; Xu, J.-P.; Callac, P.; Chen, M.-Y.; Wu, Q.; Wach, M.; Mata, G.; Zhao, R.-L. Insight into the Evolutionary and Domesticated History of the Most Widely Cultivated Mushroom Agaricus bisporus via Mitogenome Sequences of 361 Global Strains. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hu, X.-D.; Yang, R.-H.; Hsiang, T.; Wang, K.; Liang, D.-Q.; Liang, F.; Cao, D.-M.; Zhou, F.; Wen, G.; et al. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Medicinal Fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada, L.; Pakala, S.B.; Fedorova, N.D.; Joardar, V.; Shabalina, S.A.; Hostetler, J.; Pakala, S.M.; Zafar, N.; Thomas, E.; Rodriguez-Carres, M.; et al. Mobile Elements and Mitochondrial Genome Expansion in the Soil Fungus and Potato Pathogen Rhizoctonia solani AG-3. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 352, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bágeľová Poláková, S.; Lichtner, Ž.; Szemes, T.; Smolejová, M.; Sulo, P. Mitochondrial DNA Duplication, Recombination, and Introgression during Interspecific Hybridization. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freel, K.C.; Friedrich, A.; Schacherer, J. Mitochondrial Genome Evolution in Yeasts: An All-Encompassing View. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, G.; Blesa, S.; Labarere, J. Wide Distribution of Mitochondrial Genome Rearrangements in Wild Strains of the Cultivated Basidiomycete Agrocybe aegerita. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, X.; Li, J.; Martin, F.M.; Peng, W.; Tan, H. Comparative Analyses of Pleurotus pulmonarius Mitochondrial Genomes Reveal Two Major Lineages of Mini Oyster Mushroom Cultivars. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, A.I.; Putintseva, Y.A.; Simonov, E.P.; Biriukov, V.V.; Oreshkova, N.V.; Pavlov, I.N.; Sharov, V.V.; Kuzmin, D.A.; Anderson, J.B.; Krutovsky, K.V. Mobile Genetic Elements Explain Size Variation in the Mitochondrial Genomes of Four Closely-Related Armillaria Species. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambowitz, A.M. Infectious Introns. Cell 1989, 56, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfort, M.; Roberts, R.J. Homing Endonucleases: Keeping the House in Order. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3379–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoda, C.S.; Keepers, K.G.; Nadiadi, A.Y.; Bailey, D.W.; Lendemer, J.C.; Tripp, E.A.; Kane, N.C. Genome Streamlining via Complete Loss of Introns Has Occurred Multiple Times in Lichenized Fungal Mitochondria. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 4245–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, J.; Hausner, G. Organellar Introns in Fungi, Algae, and Plants. Cells 2021, 10, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, B.L. Homing Endonucleases from Mobile Group I Introns: Discovery to Genome Engineering. Mob. DNA 2014, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonen, L.; Vogel, J. The Ins and Outs of Group II Introns. Trends Genet. 2001, 17, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Q.; Fu, R.; Wang, J.; Deng, G.; Chen, X.; Lu, D. Comparative Mitochondrial Genome Analysis Reveals Intron Dynamics and Gene Rearrangements in Two Trametes Species. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Bastide, P.Y.; Sonnenberg, A.; Van Griensven, L.; Anderson, J.B.; Horgen, P.A. Mitochondrial Haplotype Influences Mycelial Growth of Agaricus bisporus Heterokaryons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3426–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudan, M.; Bou Dib, P.; Musa, M.; Kanunnikau, M.; Sobočanec, S.; Rueda, D.; Warnecke, T.; Kriško, A. Normal Mitochondrial Function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Has Become Dependent on Inefficient Splicing. eLife 2018, 7, e35330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, D.J.; McNally, K.L.; Domenico, J.M.; Matsuura, E.T. The Complete DNA Sequence of the Mitochondrial Genome of Podospora anserina. Curr. Genet. 1990, 17, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.S.; Weinstein, B.N.; Roy, S.W.; Brown, C.M. Analysis of Fungal Genomes Reveals Commonalities of Intron Gain or Loss and Functions in Intron-Poor Species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4166–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West-Eberhard, M.J. Developmental Plasticity and the Origin of Species Differences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 6543–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alster, C.J.; Allison, S.D.; Johnson, N.G.; Glassman, S.I.; Treseder, K.K. Phenotypic Plasticity of Fungal Traits in Response to Moisture and Temperature. ISME Commun. 2021, 1, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliwal, S.; Fiumera, A.C.; Fiumera, H.L. Mitochondrial-Nuclear Epistasis Contributes to Phenotypic Variation and Coadaptation in Natural Isolates of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2014, 198, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.H.M.; Sondhi, S.; Ziesel, A.; Paliwal, S.; Fiumera, H.L. Mitochondrial-Nuclear Coadaptation Revealed through mtDNA Replacements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2020, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, L.; Sillo, F.; Garbelotto, M.; Gonthier, P. Mitonuclear Interactions May Contribute to Fitness of Fungal Hybrids. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, T.M.; Burton, R.S. Differential Gene Expression and Mitonuclear Incompatibilities in Fast- and Slow-Developing Interpopulation Tigriopus californicus Hybrids. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 3102–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Hu, F.; Wang, Z.; Lyu, J.; Wang, B.; Xiang, H.; Zhao, R.; Tian, Z.; et al. Decrease of Gene Expression Diversity during Domestication of Animals and Plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Ma, X.-B.; Han, B.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.-P.; Cao, B.; Ling, Z.-L.; He, M.-Q.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Zhao, R.-L. Pan-Genome Analysis Reveals Genomic Variations during Enoki Mushroom Domestication, with Emphasis on Genetic Signatures of Cap Color and Stipe Length. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 75, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Goyal, J.; Dillingham, M.E.; Bakerlee, C.W.; Humphrey, P.T.; Jagdish, T.; Jerison, E.R.; Kosheleva, K.; Lawrence, K.R.; et al. Phenotypic and Molecular Evolution across 10,000 Generations in Laboratory Budding Yeast Populations. eLife 2021, 10, e63910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallone, B.; Steensels, J.; Prahl, T.; Soriaga, L.; Saels, V.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Merlevede, A.; Roncoroni, M.; Voordeckers, K.; Miraglia, L.; et al. Domestication and Divergence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Beer Yeasts. Cell 2016, 166, 1397–1410.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strains | Gene | Intron Number | Intron Class a | Intron Length (bp) | Intronic ORF | Conserved Domain of HEGs | Number of Repeat Motifs (HEs) | Intronic Region in cox1 Gene (bp) | Coding Sequence (CDS) Region | Fisrt Amino Acid (CDS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dkN001 | cox1 | I1 | IB | 1742 | orf395 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 235–1976 | 235–1422 | K (Lysine) |

| cox1 | I2 | IB | 1391 | orf385 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 1 | 2123–3510 | 2124–3281 | L (Leucine) | |

| cox1 | I3 | IB | 1233 | orf284 | LAGLIDADG_2 | 1 | 4096–5328 | 4097–4951 | S (Serine) | |

| cox1 | I4 | IB | 1335 | orf293 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 5465–6799 | 5465–6346 | R (Arginine) | |

| cox1 | I5 | IB | 1156 | orf378 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 1 | 6818–7973 | 6818–7954 | Q (Glutamine) | |

| cox1 | I6 | IA | 1283 | orf267 | GIY-YIG | 1 | 8154–9436 | 8154–8957 | V (Valine) | |

| dkF515 | cox1 | I1 | IB | 1456 | orf387 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 381–1836 | 382–1545 | L (Leucine) |

| cox1 | I2 | IB | 1170 | orf329 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 2066–3235 | 2066–3055 | K (Lysine) | |

| cox1 | I3 | IB | 2536 | orf317 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 3341–5876 | 3341–4294 | I (Isoleucine) | |

| cox1 | I3 | IB | 2536 | orf305 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 1 | 3341–5876 | 4882–5799 | M (Methionine) | |

| cox1 | I4 | IB | 1110 | orf336 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 6057–7166 | 6057–7067 | R (Arginine) | |

| cox1 | I5 | IB | 1215 | orf286 | LAGLIDADG_2 | 1 | 7238–8452 | 7239–8099 | S (Serine) | |

| cox1 | I6 | IB | 1347 | orf293 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 1 | 8589–9935 | 8589–9470 | R (Arginine) | |

| cox1 | I7 | IA | 1287 | orf267 | GIY-YIG | 1 | 10,134–11,420 | 10,134–10,937 | V (Valine) | |

| dkN009 | cox1 | I1 | IB | 1456 | orf387 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 381–1836 | 382–1545 | L (Leucine) |

| cox1 | I2 | IB | 1170 | orf329 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 2066–3235 | 2066–3055 | K (Lysine) | |

| cox1 | I3 | IB | 2533 | orf317 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 3341–5873 | 3341–4294 | I (Isoleucine) | |

| cox1 | I3 | IB | 2533 | orf305 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 1 | 3341–5873 | 4880–5797 | M (Methionine) | |

| cox1 | I4 | IB | 1110 | orf336 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 6054–7163 | 6054–7064 | R (Arginine) | |

| cox1 | I5 | IB | 1215 | orf286 | LAGLIDADG_2 | 1 | 7235–8449 | 7236–8096 | S (Serine) | |

| cox1 | I6 | IB | 1150 | orf278 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 2 | 8586–9735 | 8586–9422 | T (Threonine) | |

| cox1 | I7 | IB | 1156 | orf378 | LAGLIDADG_1 | 1 | 9754–10,909 | 9754–10,890 | Q (Glutamine) | |

| cox1 | I8 | IA | 1287 | orf267 | GIY-YIG | 1 | 11,090–12,376 | 11,090–11,893 | V (Valine) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pérez, G.; Jiménez, I.; Garde, E.; Ramírez, L.; Pisabarro, A.G. Comparative Mitogenomics Reveals Intron Dynamics and Mitochondrial Gene Expression Shifts in Domesticated and Wild Pleurotus ostreatus. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010075

Pérez G, Jiménez I, Garde E, Ramírez L, Pisabarro AG. Comparative Mitogenomics Reveals Intron Dynamics and Mitochondrial Gene Expression Shifts in Domesticated and Wild Pleurotus ostreatus. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010075

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez, Gumer, Idoia Jiménez, Edurne Garde, Lucía Ramírez, and Antonio G. Pisabarro. 2026. "Comparative Mitogenomics Reveals Intron Dynamics and Mitochondrial Gene Expression Shifts in Domesticated and Wild Pleurotus ostreatus" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010075

APA StylePérez, G., Jiménez, I., Garde, E., Ramírez, L., & Pisabarro, A. G. (2026). Comparative Mitogenomics Reveals Intron Dynamics and Mitochondrial Gene Expression Shifts in Domesticated and Wild Pleurotus ostreatus. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010075