Chromoblastomycosis in French Guiana: Epidemiology and Practices, 1955–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

- Mild (single plaque or nodule less than 5 cm);

- Moderate (one or more nodular lesions, plaque or verrucous less than 15 cm in one or two adjacent areas);

- Severe (lesion larger than 15 cm or several non-adjacent areas). Species identification was based on their morphological characters on positive fungal culture.

3. Results

3.1. Demography

3.2. Clinical Presentation

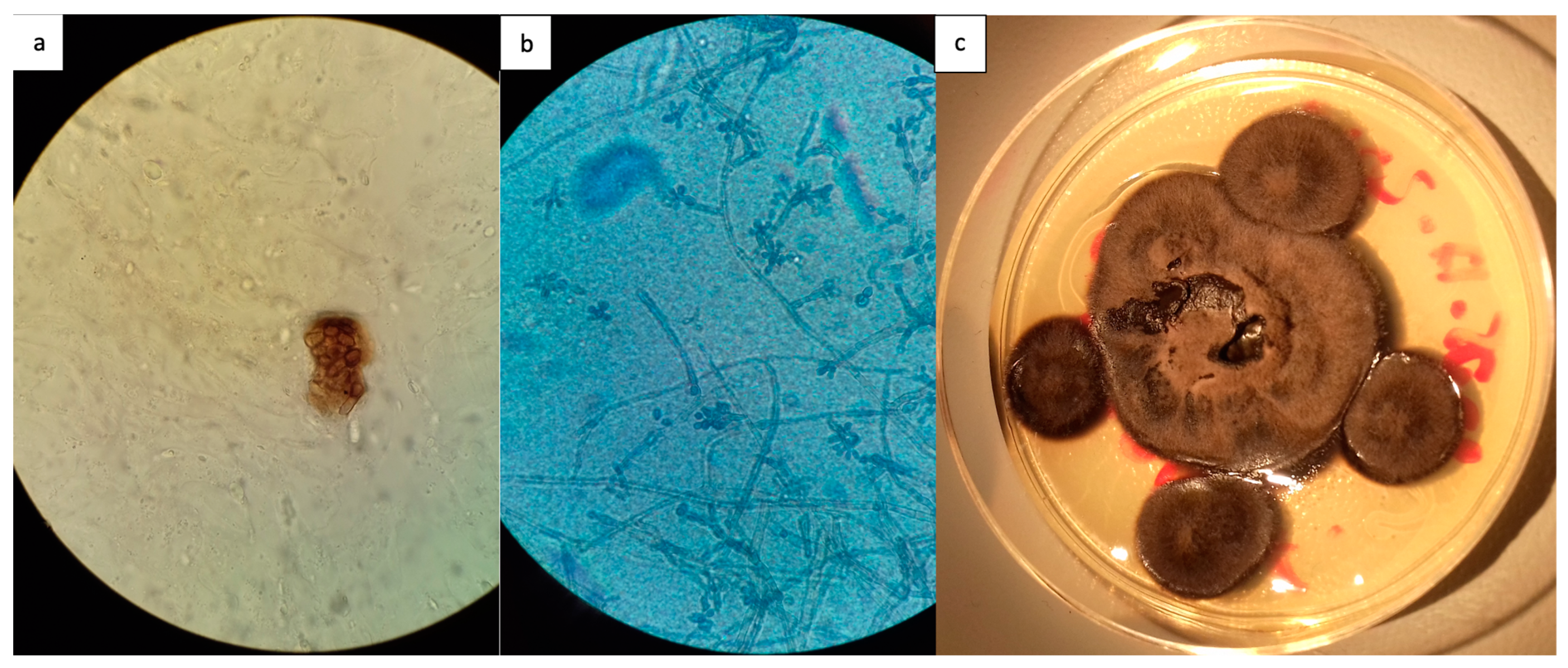

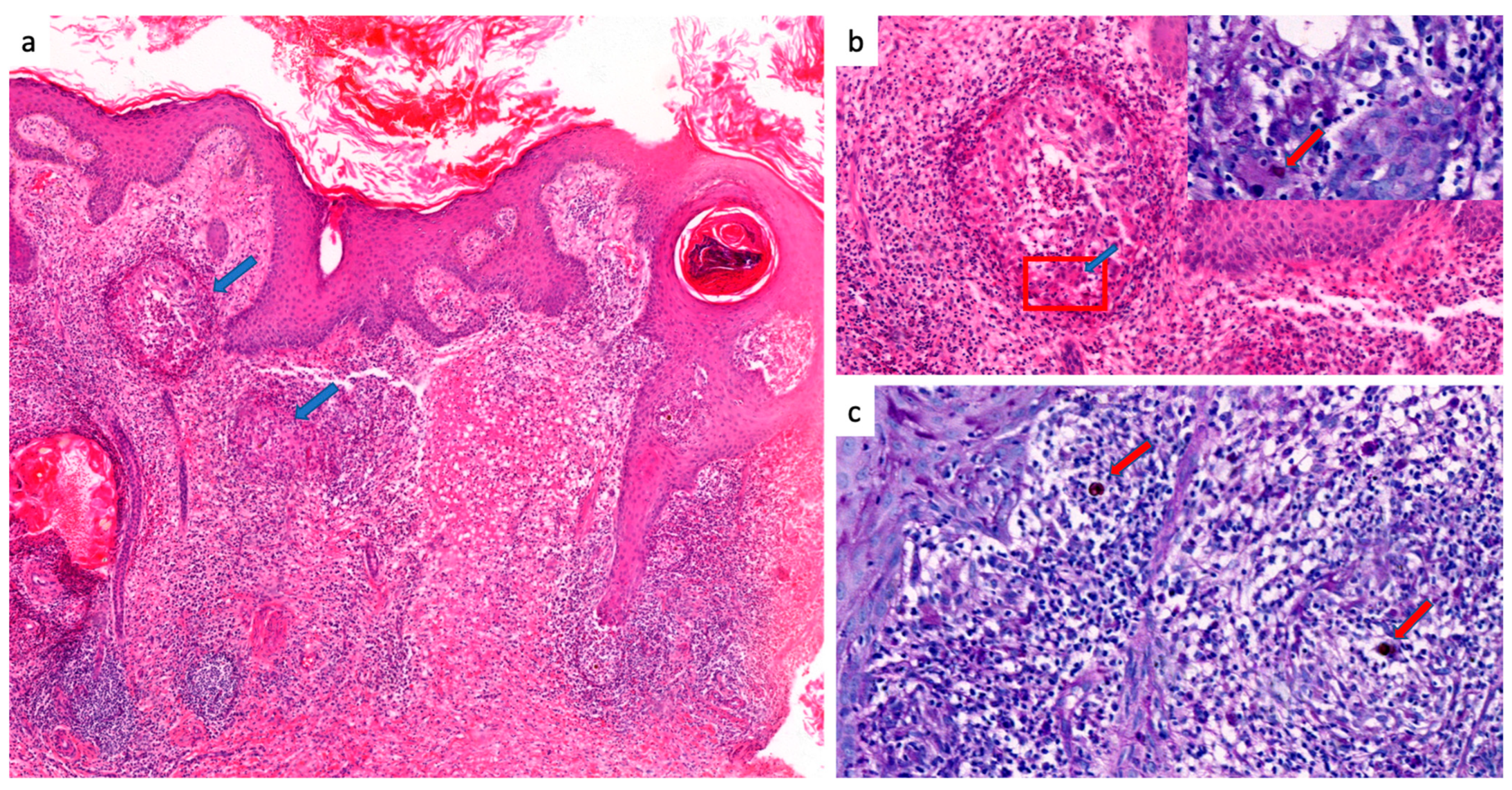

3.3. Laboratory Tests

3.4. Therapeutic Regimen

3.5. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Queiroz-Telles, F.; Fahal, A.H.; Falci, D.R.; Caceres, D.H.; Chiller, T.; Pasqualotto, A.C. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e367–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Telles, F.; Esterre, P.; Perez-Blanco, M.; Vitale, R.G.; Salgado, C.G.; Bonifaz, A. Chromoblastomycosis: An overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M. Chromoblastomycosis: Clinical presentation and management. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.W.C.L.; de Azevedo, C.d.M.P.E.S.; Vicente, V.A.; Queiroz-Telles, F.; Rodrigues, A.M.; de Hoog, G.S.; Denning, D.W.; Colombo, A.L. The global burden of chromoblastomycosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brito, A.C.; Bittencourt, M.d.J.S. Chromoblastomycosis: An etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2018, 93, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuneto, L.T.; Arce-Gomez, B.; Petzl-Erler, M.L.; Queiroz-Telles, F. HLA-A29 and genetic susceptibility to chromoblastomycosis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 1989, 27, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Y.; Song, Y.; Wan, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, R. CARD9 deficiency predisposing chromoblastomycosis: A case report and comparative transcriptome study. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 984093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhi, H.; Shen, H.; Lv, W.; Sang, B.; Li, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xia, X. Chromoblastomycosis: A case series from Eastern China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendrasoa, F.A.; Ratovonjanahary, V.T.; Rasamoelina, T.; Ramarozatovo, L.S.; Rapelanoro Rabenja, F. Treatment responses in patients with chromoblastomycosis to itraconazole in Madagascar. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Telles, F.; de Hoog, S.; Santos, D.W.C.L.; Salgado, C.G.; Vicente, V.A.; Bonifaz, A.; Roilides, E.; Xi, L.; Azevedo, C.d.M.P.E.S.; da Silva, M.B.; et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 233–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Liu, W.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, D. Muriform Cells Can Reproduce by Dividing in an Athymic Murine Model of Chromoblastomycosis due to Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Telles, F.; Santos, D.W.C.L. Chromoblastomycosis in the Clinical Practice. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2012, 6, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, A.; Gomes, J. Sobre quatro casos de dermatite verrucosa produzida por Phialophora verrucosa. Paul. Med. Cir. 1920, 11, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Clyti, E.; Couppie, P.; Heid, E.; Sainte Marie, D.; Pradinaud, R. [Keratosic knee nodule]. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001, 128, 549–550. [Google Scholar]

- Pradinaud, R.; Joly, F.; Basset, M.; Basset, A.; Grosshans, E. [Chromomycosis and Jorge Lobo disease in French Guiana]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1969, 62, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Silverie, R.; Ravisse, P. [On 2 cases of chromomycosis observed in French Guiana]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1962, 55, 751–752. [Google Scholar]

- Pradinaud, R. [Letter: Treatment of 6 chromomycoses by 5 fluoro-cytosine in French Guyana]. Nouv. Presse Med. 1974, 3, 1955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lupi, O.; Tyring, S.K.; McGinnis, M.R. Tropical dermatology: Fungal tropical diseases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 53, 931–951, quiz 952–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.W.C.L.; Vicente, V.A.; Weiss, V.A.; de Hoog, G.S.; Gomes, R.R.; Batista, E.M.M.; Marques, S.G.; de Queiroz-Telles, F.; Colombo, A.L.; De Azevedo, C.d.M.P.E.S. Chromoblastomycosis in an Endemic Area of Brazil: A Clinical-Epidemiological Analysis and a Worldwide Haplotype Network. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrame, A.; Danesi, P.; Farina, C.; Orza, P.; Perandin, F.; Zanardello, C.; Rodari, P.; Staffolani, S.; Bisoffi, Z. Case Report: Molecular Confirmation of Lobomycosis in an Italian Traveler Acquired in the Amazon Region of Venezuela. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 1757–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P.; Jindal, R.; Shirazi, N. Dermoscopy of Chromoblastomycosis. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2019, 10, 759–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.; Denning, D.W.; Bonifaz, A.; Queiroz-Telles, F.; Beer, K.; Bustamante, B.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chavez-Lopez, M.d.G.; Chiller, T.; Cornet, M.; et al. The Diagnosis of Fungal Neglected Tropical Diseases (Fungal NTDs) and the Role of Investigation and Laboratory Tests: An Expert Consensus Report. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, A.; Nery, A.F.; de Souza Carvalho Melhem, M.; Bonfietti, L.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Hagen, F.; de Carvalho, J.A.; de Camargo, Z.P.; de Souza Lima, B.J.F.; Vicente, V.A.; et al. Molecular epidemiology and clinical-laboratory aspects of chromoblastomycosis in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mycoses 2022, 65, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe-J, F.; Zuluaga, A.I.; Leon, W.; Restrepo, A. Histopathology of chromoblastomycosis. Mycopathologia 1989, 105, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienvenu, A.-L.; Picot, S. Mycetoma and Chromoblastomycosis: Perspective for Diagnosis Improvement Using Biomarkers. Molecules 2020, 25, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maubon, D.; Garnaud, C.; Ramarozatovo, L.S.; Fahafahantsoa, R.R.; Cornet, M.; Rasamoelina, T. Molecular Diagnosis of Two Major Implantation Mycoses: Chromoblastomycosis and Sporotrichosis. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, M.S.M.; Castro, L.G.M.; Cavalcante, S.C.; Lacaz, C.S. Highly specific and sensitive, immunoblot-detected 54 kDa antigen from Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Med. Mycol. 2004, 42, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heleine, M.; Blaizot, R.; Cissé, H.; Labaudinière, A.; Guerin, M.; Demar, M.; Blanchet, D.; Couppie, P. A case of disseminated paracoccidioidomycosis associated with cutaneous lobomycosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e18–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidakey, G.P.; Snow, S.N.; Mohs, F.E. Chromoblastomycosis treated by Mohs micrographic surgery. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1986, 12, 1073–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, G.; Oliveira, A.d.S.; Verde, S.F.; Martins, O.; Picoto, A.d.S. Chromomycosis: Report of a case and management by cryosurgery, topical chemotherapy, and conventional surgery. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1980, 6, 576–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.A.; Brito-Santos, F.; Figueiredo-Carvalho, M.H.G.; Silva, J.V.D.S.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; do Valle, A.C.F.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; Trilles, L.; Meyer, W.; Freitas, D.F.S.; et al. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of clinical strains of Fonsecaea spp. isolated from patients with chromoblastomycosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daboit, T.C.; Massotti Magagnin, C.; Heidrich, D.; Czekster Antochevis, L.; Vigolo, S.; Collares Meirelles, L.; Alves, K.; Scroferneker, M.L. In vitro susceptibility of chromoblastomycosis agents to five antifungal drugs and to the combination of terbinafine and amphotericin B. Mycoses 2014, 57, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Taborda, P.R.; Sanzovo, A.D. Alternate week and combination itraconazole and terbinafine therapy for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea pedrosoi in Brazil. Med. Mycol. 2002, 40, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroni, R.; Tobón, A.; Bustamante, B.; Shikanai-Yasuda, M.A.; Patino, H.; Restrepo, A. Posaconazole treatment of refractory eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2005, 47, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, M.d.G.T.; Belda, W.; Spina, R.; Lota, P.R.; Valente, N.S.; Brown, G.D.; Criado, P.R.; Benard, G. Topical application of imiquimod as a treatment for chromoblastomycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1734–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, V.F.; Kneipp, L.F.; Rozental, S.; Alviano, C.S.; Santos, A.L.S. Beneficial effects of HIV peptidase inhibitors on Fonsecaea pedrosoi: Promising compounds to arrest key fungal biological processes and virulence. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vf, P.; Frv, G.; Mq, G.; Ds, A.; Cs, A.; Lf, K.; Als, S. Fonsecaea pedrosoi Sclerotic Cells: Secretion of Aspartic-Type Peptidase and Susceptibility to Peptidase Inhibitors. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, J.P.; Moreira, L.M.; de Carvalho, V.S.D.; dos Santos, F.V.; de Lima, C.J.; de Resende, M.A. In vitro photodynamic therapy against Foncecaea pedrosoi and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses 2013, 56, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qi, X.; Sun, H.; Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, K.; Yang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Photodynamic therapy combined with antifungal drugs against chromoblastomycosis and the effect of ALA-PDT on Fonsecaea in vitro. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J. Retinoid combined with photodynamic therapy against hyperkeratotic chromoblastomycosis: A case report and literature review. Mycoses 2021, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number of Patients n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender ● Female ● Male | ● 3 (13) ● 20 (87) |

| Median age at diagnosis | 60 (43–74) |

| Ethnicity ● Creole ● Haitian ● Surinamese ● Maroon ● Brazilian ● French (mainland) ● Saint-Lucian ● Unknown | ● 11 (47.8) ● 3 (13) ● 2 (8.7) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 3 (13) |

| Occupation ● Farmer ● Gold digger ● Warehouseman a ● Forestry worker ● Gardener ● Hunter ● Ornithologist ● Mason ● Unknown | ● 10 (43.3) ● 2 (8.7) ● 2 (8.7) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 4 (17.4) |

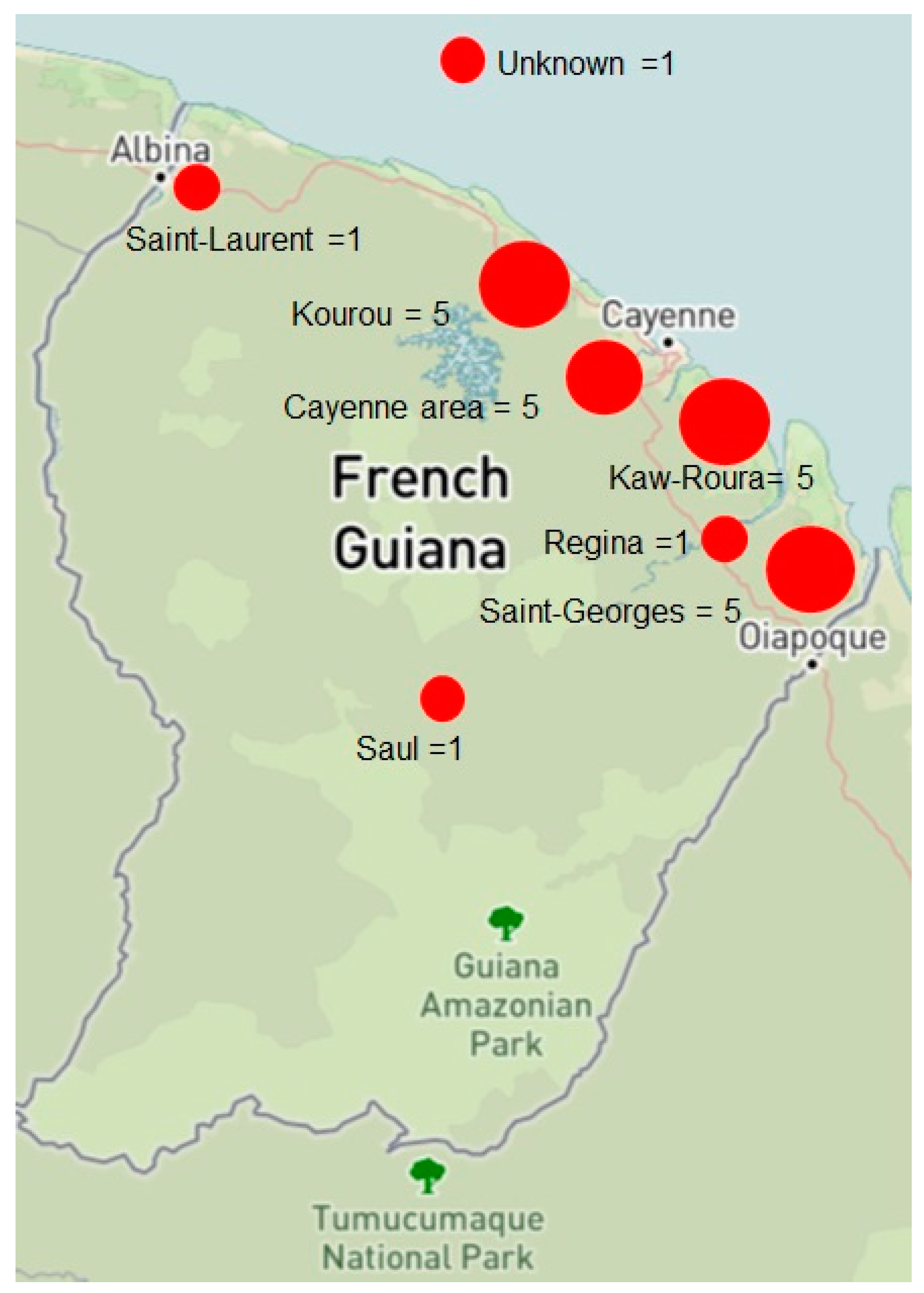

| Likely place of contamination ● Kaw and Roura ● Kourou area (Montsinéry) ● Saint-Georges-de-l’Oyapock ● Cayenne urban area (Matoury, Macouria) ● Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni ● Saül ● Regina ● Unknown | ● 5 (21.7) ● 5 (21.7) ● 5 (21.7) ● 4 (17.4) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) |

| Underlying condition ● Digestive parasitosis b ● Cutaneous leishmaniasis ● Vascular (high blood pressure, stroke) ● Prostate carcinoma ● None ● Unknown | ● 6 (26.1) ● 2 (8.7) ● 2 (8.7) ● 1 (4.3) ● 3 (13) ● 11 (47.8) |

| Clinical Presentation | Number of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Lesion type ● Cicatricial ● Verrucous ● Nodular ● Tumoral ● Plaque ● Mixed | ● 5 (21.7) ● 5 (21.7) ● 3 (13) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) ● 8 (34.8) |

| Clinical severity ● Mild ● Moderate ● Severe | ● 3 (13) ● 12 (52.2) ● 7 (30.4) |

| Associated symptoms ● Pruritus ● Pain ● Edema ● Lymphadenitis ● Functional limitation | ● 5 (26.1) ● 4 (17.4) ● 2 (8.7) ● 1 (4.3) ● 1 (4.3) |

| Outcome | Antifungals Alone n = 13 | Antifungals + Surgical Excision (n = 3) | Antifungals + Cryotherapy (n = 3) | Unknown (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cured | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (66.7%) | - |

| Partially cured | 5 (38.5%) | - | 1 (33.3%) | - |

| Not cured | 1 (7.7%) | - | - | - |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (33.3%) | - | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valentin, J.; Grotta, G.; Muller, T.; Bourgeois, P.; Drak Alsibai, K.; Demar, M.; Couppie, P.; Blaizot, R. Chromoblastomycosis in French Guiana: Epidemiology and Practices, 1955–2023. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10030168

Valentin J, Grotta G, Muller T, Bourgeois P, Drak Alsibai K, Demar M, Couppie P, Blaizot R. Chromoblastomycosis in French Guiana: Epidemiology and Practices, 1955–2023. Journal of Fungi. 2024; 10(3):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10030168

Chicago/Turabian StyleValentin, Julie, Geoffrey Grotta, Thibaut Muller, Pieter Bourgeois, Kinan Drak Alsibai, Magalie Demar, Pierre Couppie, and Romain Blaizot. 2024. "Chromoblastomycosis in French Guiana: Epidemiology and Practices, 1955–2023" Journal of Fungi 10, no. 3: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10030168

APA StyleValentin, J., Grotta, G., Muller, T., Bourgeois, P., Drak Alsibai, K., Demar, M., Couppie, P., & Blaizot, R. (2024). Chromoblastomycosis in French Guiana: Epidemiology and Practices, 1955–2023. Journal of Fungi, 10(3), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10030168