Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential of Human Cardiomyocyte Proliferation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Models of Heart Regeneration

2.1. Non-Human Models

2.1.1. Zebrafish

2.1.2. Mice

2.1.3. Pigs

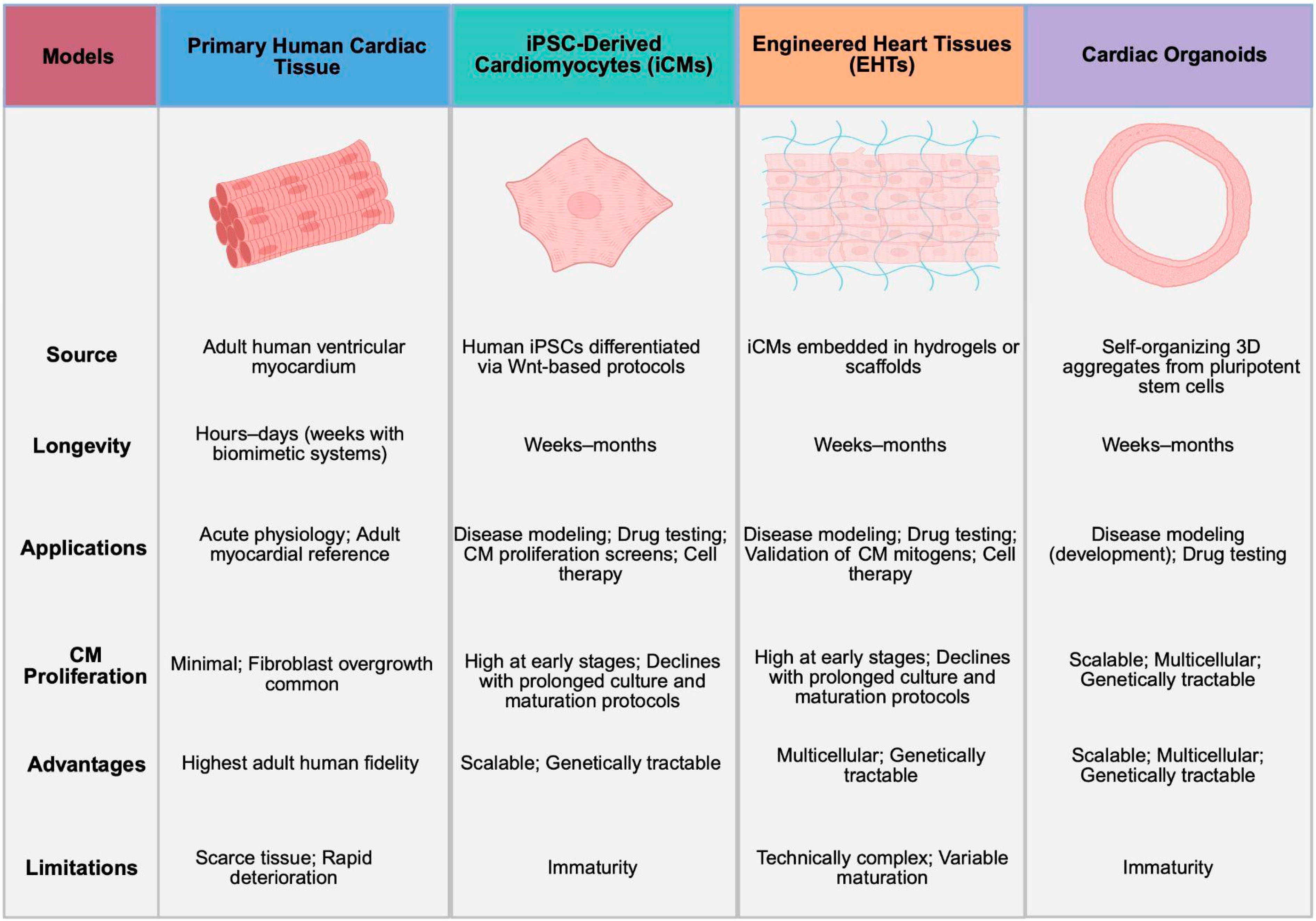

2.2. Human Models

2.2.1. Primary Human Cardiac Tissue

2.2.2. iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes (iCMs)

2.2.3. Engineered Heart Tissues (EHTs)

2.2.4. Cardiac Organoids

2.2.5. Current Controversies and Limitations

3. Cardiomyocyte Proliferation in the Human Heart

3.1. Developmental Cardiomyocyte Proliferation

3.2. Postnatal Cardiomyocyte Proliferation

4. Therapeutic Heart Regeneration

4.1. Cardiac Recovery in Neonatal Humans

4.2. Cardiac Recovery with Mechanical Unloading

4.3. Emerging Regenerative Therapeutics

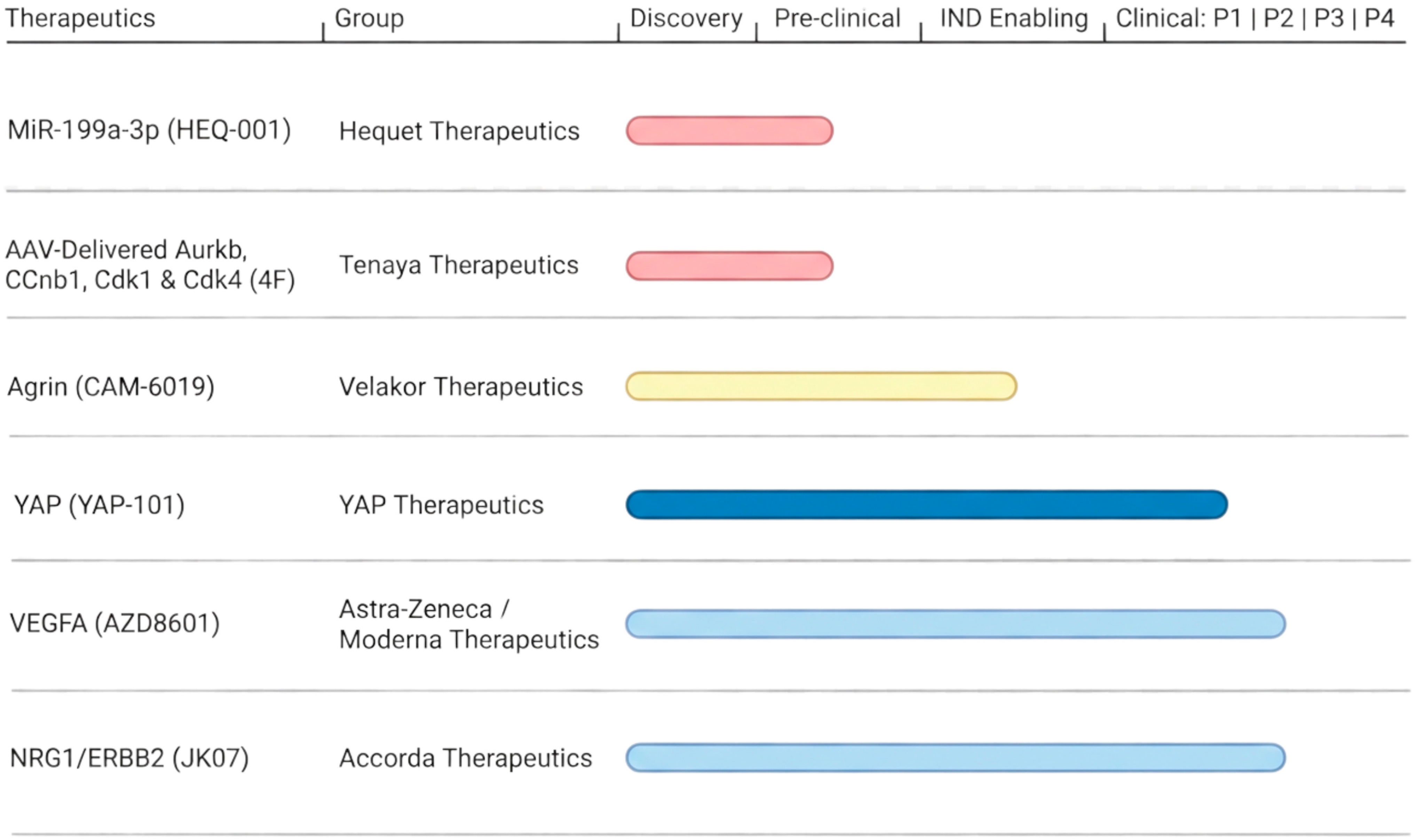

4.3.1. MicroRNAs

4.3.2. Transient Cell Cycle Activators

4.3.3. Agrin

4.3.4. VEGFA

4.3.5. NRG1/ERBB Signaling

4.3.6. Hippo/YAP Signaling

5. Challenges for Therapeutic Heart Regeneration

5.1. Arrhythmic Risk

5.2. Gene Delivery

5.3. Oncogenic Risk

5.4. Trial Design

6. Future Directions in Cardiac Regeneration

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CM | Cardiomyocyte |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EHTs | Engineered heart tissues |

| iCMs | Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

| LVAD | Left ventricular assist device |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MIMS | Multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| modRNA | Modified messenger RNA |

| PSC | Pluripotent stem cell |

| ToF | Tetralogy of Fallot |

| wpc | Weeks post-conception |

References

- Writing Committee Members. HF STATS 2025: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics An Updated 2025 Report from the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Opsha, Y.; Sandhu, A.T.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Warraich, H.J.; HFSA Scientific Statement Committee Members Chair. Economic Issues in Heart Failure in the United States. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kirk, J.; Fudim, M.; Green, C.L.; Karra, R. Heterogeneous outcomes of heart failure with better ejection fraction. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2019, 13, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, J.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; Ardehali, H.; Bonow, R.O.; Butler, J.; Sauer, A.J.; Epstein, S.E.; Khan, S.S.; Kim, R.J.; Sabbah, H.N.; et al. “Targeting the Heart” in Heart Failure: Myocardial Recovery in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberpriller, J.; Oberpriller, J.C. Mitosis in adult newt ventricle. J. Cell Biol. 1971, 49, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberpriller, J.O.; Oberpriller, J.C. Response of the adult newt ventricle to injury. J. Exp. Zool. 1974, 187, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poss, K.D.; Wilson, L.G.; Keating, M.T. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science 2002, 298, 2188–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Holdway, J.E.; Werdich, A.A.; Anderson, R.M.; Fang, Y.; Egnaczyk, G.F.; Evans, T.; Macrae, C.A.; Stainier, D.Y.; Poss, K.D. Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4(+) cardiomyocytes. Nature 2010, 464, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jopling, C.; Sleep, E.; Raya, M.; Marti, M.; Raya, A.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature 2010, 464, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrello, E.R.; Mahmoud, A.I.; Simpson, E.; Hill, J.A.; Richardson, J.A.; Olson, E.N.; Sadek, H.A. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science 2011, 331, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Karra, R.; Dickson, A.L.; Poss, K.D. Fibronectin is deposited by injury-activated epicardial cells and is necessary for zebrafish heart regeneration. Dev. Biol. 2013, 382, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chablais, F.; Veit, J.; Rainer, G.; Jazwinska, A. The zebrafish heart regenerates after cryoinjury-induced myocardial infarction. BMC Dev. Biol. 2011, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rosa, J.M.; Mercader, N. Cryoinjury as a myocardial infarction model for the study of cardiac regeneration in the zebrafish. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.E.; Bakovic, M.; Karra, R. Endothelial Contributions to Zebrafish Heart Regeneration. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2018, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, R.; Foglia, M.J.; Choi, W.Y.; Belliveau, C.; DeBenedittis, P.; Poss, K.D. Vegfaa instructs cardiac muscle hyperplasia in adult zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8805–8810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemberling, M.; Karra, R.; Dickson, A.L.; Poss, K.D. Nrg1 is an injury-induced cardiomyocyte mitogen for the endogenous heart regeneration program in zebrafish. Elife 2015, 4, e05871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.P.; Sheng, D.Z.; Sugimoto, K.; Gonzalez-Rajal, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Hesselson, D.; Kikuchi, K. Zebrafish Regulatory T Cells Mediate Organ-Specific Regenerative Programs. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 659–672 e655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iranzo, H.; Galardi-Castilla, M.; Minguillon, C.; Sanz-Morejon, A.; Gonzalez-Rosa, J.M.; Felker, A.; Ernst, A.; Guzman-Martinez, G.; Mosimann, C.; Mercader, N. Tbx5a lineage tracing shows cardiomyocyte plasticity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, R.; Knecht, A.K.; Kikuchi, K.; Poss, K.D. Myocardial NF-kappaB activation is essential for zebrafish heart regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13255–13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Hu, J.; Karra, R.; Dickson, A.L.; Tornini, V.A.; Nachtrab, G.; Gemberling, M.; Goldman, J.A.; Black, B.L.; Poss, K.D. Modulation of tissue repair by regeneration enhancer elements. Nature 2016, 532, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkoop, H.; de Bakker, D.E.; Aharonov, A.; Kruse, F.; Shakked, A.; Nguyen, P.D.; de Heus, C.; Garric, L.; Muraro, M.J.; Shoffner, A. Single-cell analysis uncovers that metabolic reprogramming by ErbB2 signaling is essential for cardiomyocyte proliferation in the regenerating heart. Elife 2019, 8, e50163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, M.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Gao, J.; Xu, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. An organ-wide spatiotemporal transcriptomic and cellular atlas of the regenerating zebrafish heart. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Rosa, J.M.; Sharpe, M.; Field, D.; Soonpaa, M.H.; Field, L.J.; Burns, C.E.; Burns, C.G. Myocardial polyploidization creates a barrier to heart regeneration in zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 433–446. e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturzu, A.C.; Rajarajan, K.; Passer, D.; Plonowska, K.; Riley, A.; Tan, T.C.; Sharma, A.; Xu, A.F.; Engels, M.C.; Feistritzer, R.; et al. Fetal Mammalian Heart Generates a Robust Compensatory Response to Cell Loss. Circulation 2015, 132, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrello, E.R.; Mahmoud, A.I.; Simpson, E.; Johnson, B.A.; Grinsfelder, D.; Canseco, D.; Mammen, P.P.; Rothermel, B.A.; Olson, E.N.; Sadek, H.A. Regulation of neonatal and adult mammalian heart regeneration by the miR-15 family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBenedittis, P.; Karpurapu, A.; Henry, A.; Thomas, M.C.; McCord, T.J.; Brezitski, K.; Prasad, A.; Baker, C.E.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shah, S.H. Coupled myovascular expansion directs cardiac growth and regeneration. Development 2022, 149, dev200654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.; Barske, L.; Van Handel, B.; Rau, C.D.; Gan, P.; Sharma, A.; Parikh, S.; Denholtz, M.; Huang, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; et al. Frequency of mononuclear diploid cardiomyocytes underlies natural variation in heart regeneration. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurora, A.B.; Porrello, E.R.; Tan, W.; Mahmoud, A.I.; Hill, J.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Sadek, H.A.; Olson, E.N. Macrophages are required for neonatal heart regeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, T.; van Rooij, E. Molecular gatekeepers of endogenous adult mammalian cardiomyocyte proliferation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 857–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenhagen, T.; Bolli, R.; Braun, T.; Field, L.J.; Fleischmann, B.K.; Frisen, J.; Giacca, M.; Hare, J.M.; Houser, S.; Lee, R.T.; et al. Cardiomyocyte Regeneration: A Consensus Statement. Circulation 2017, 136, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Uva, G.; Aharonov, A.; Lauriola, M.; Kain, D.; Yahalom-Ronen, Y.; Carvalho, S.; Weisinger, K.; Bassat, E.; Rajchman, D.; Yifa, O.; et al. ERBB2 triggers mammalian heart regeneration by promoting cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; D’Agostino, G.; Loo, S.J.; Wang, C.X.; Su, L.P.; Tan, S.H.; Tee, G.Z.; Pua, C.J.; Pena, E.M.; Cheng, R.B.; et al. Early Regenerative Capacity in the Porcine Heart. Circulation 2018, 138, 2798–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, E.; Zhao, M.; Chong, Z.; Fan, C.; Tang, Y.; Hunter, J.D.; Borovjagin, A.V.; Walcott, G.P.; Chen, J.Y.; et al. Regenerative Potential of Neonatal Porcine Hearts. Circulation 2018, 138, 2809–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.D.; Ranjan, A.K.; Kawase, Y.; Cheng, R.K.; Kara, R.J.; Bhattacharya, R.; Guzman-Martinez, G.; Sanz, J.; Garcia, M.J.; Chaudhry, H.W. Cyclin A2 induces cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction through cytokinesis of adult cardiomyocytes. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, K.; Wagner Florencio, L.; Tang, L.; Heallen, T.R.; Leach, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Grisanti, F.; Willerson, J.T.; Perin, E.C.; et al. Gene therapy knockdown of Hippo signaling induces cardiomyocyte renewal in pigs after myocardial infarction. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehr, A.; Umansky, K.B.; Bassat, E.; Jurisch, V.; Klett, K.; Bozoglu, T.; Hornaschewitz, N.; Solyanik, O.; Kain, D.; Ferraro, B.; et al. Agrin Promotes Coordinated Therapeutic Processes Leading to Improved Cardiac Repair in Pigs. Circulation 2020, 142, 868–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabisonia, K.; Prosdocimo, G.; Aquaro, G.D.; Carlucci, L.; Zentilin, L.; Secco, I.; Ali, H.; Braga, L.; Gorgodze, N.; Bernini, F.; et al. MicroRNA therapy stimulates uncontrolled cardiac repair after myocardial infarction in pigs. Nature 2019, 569, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, W.; Bergmann, O. Polyploidy in Cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, S.K.; Purdy, A.L.; Kolell, M.E.; Andresen, K.G.; Lahue, C.; Buddell, T.; Akins, K.A.; Rau, C.D.; O’Meara, C.C.; Patterson, M. Cardiomyocyte ploidy is dynamic during postnatal development and varies across genetic backgrounds. Development 2023, 150, dev201318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglen, T.; Kaplow, I.M.; Choi, B.; Dewars, E.; Perelli, R.M.; Hagy, K.T.; Tran, D.; Ramaker, M.E.; Shah, S.H.; Jung, I.; et al. A gene regulatory element modulates myosin expression and controls cardiomyocyte response to stress. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 2418–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.J.; Song, K.; Luo, X.; Daniel, E.; Lambeth, K.; West, K.; Hill, J.A.; DiMaio, J.M.; Baker, L.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; et al. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward a cardiac fate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5588–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, K.; Jones-Tabah, J.; Pétrin, D.; Martin, R.D.; Tanny, J.C.; Hébert, T.E. Comparing the signaling and transcriptome profiling landscapes of human iPSC-derived and primary rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.M.; Nesti, C.; Palenzuela, L.; Walker, W.F.; Hernandez, E.; Protas, L.; Hirano, M.; Isaac, N.D. Novel cell lines derived from adult human ventricular cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2005, 39, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geest, J.S.A.; de Boer, T.P.; Terracciano, C.M.; Thum, T.; Dendorfer, A.; Doevendans, P.A.; van Laake, L.W.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Sampaio-Pinto, V. Living myocardial slices: Walking the path towards standardization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.A.; Duff, J.; Bardi, I.; Zabielska, M.; Atanur, S.S.; Jabbour, R.J.; Simon, A.; Tomas, A.; Smolenski, R.T.; Harding, S.E.; et al. Biomimetic electromechanical stimulation to maintain adult myocardial slices in vitro. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Q.; Jacobson, Z.; Abouleisa, R.R.; Tang, X.-L.; Hindi, S.M.; Kumar, A.; Ivey, K.N.; Giridharan, G.; El-Baz, A.; Brittian, K. Physiological biomimetic culture system for pig and human heart slices. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.; Milting, H.; Fein, E.; Reiser, E.; Lu, K.; Seidel, T.; Schinner, C.; Schwarzmayr, T.; Schramm, R.; Tomasi, R.; et al. Long-term functional and structural preservation of precision-cut human myocardium under continuous electromechanical stimulation in vitro. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyra-Leite, D.M.; Gutierrez-Gutierrez, O.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Cyganek, L.; Burridge, P.W. A review of protocols for human iPSC culture, cardiac differentiation, subtype-specification, maturation, and direct reprogramming. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, P.W.; Matsa, E.; Shukla, P.; Lin, Z.C.; Churko, J.M.; Ebert, A.D.; Lan, F.; Diecke, S.; Huber, B.; Mordwinkin, N.M.; et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, X.; Bao, X.; Zilberter, M.; Westman, M.; Fisahn, A.; Hsiao, C.; Hazeltine, L.B.; Dunn, K.K.; Kamp, T.J.; Palecek, S.P. Chemically defined, albumin-free human cardiomyocyte generation. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Hsiao, C.; Wilson, G.; Zhu, K.; Hazeltine, L.B.; Azarin, S.M.; Raval, K.K.; Zhang, J.; Kamp, T.J.; Palecek, S.P. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E1848–E1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakikes, I.; Ameen, M.; Termglinchan, V.; Wu, J.C. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: Insights into molecular, cellular, and functional phenotypes. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, L.; Karra, R. The (Pluri)Potential of Cell Therapy for Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neininger, A.C.; Long, J.H.; Baillargeon, S.M.; Burnette, D.T. A simple and flexible high-throughput method for the study of cardiomyocyte proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renikunta, H.V.; Lazarow, K.; Gong, Y.; Shukla, P.C.; Nageswaran, V.; Giral, H.; Kratzer, A.; Opitz, L.; Engel, F.B.; Haghikia, A.; et al. Large-scale microRNA functional high-throughput screening identifies miR-515-3p and miR-519e-3p as inducers of human cardiomyocyte proliferation. iScience 2023, 26, 106593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titmarsh, D.M.; Glass, N.R.; Mills, R.J.; Hidalgo, A.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Porrello, E.R.; Hudson, J.E.; Cooper-White, J.J. Induction of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte proliferation revealed by combinatorial screening in high density microbioreactor arrays. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murganti, F.; Derks, W.; Baniol, M.; Simonova, I.; Trus, P.; Neumann, K.; Khattak, S.; Guan, K.; Bergmann, O. FUCCI-Based Live Imaging Platform Reveals Cell Cycle Dynamics and Identifies Pro-proliferative Compounds in Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 840147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintruba, K.L.; Wolf, M.J.; van Berlo, J.H.; Saucerman, J.J. Advances in Drug Discovery for Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 27, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, L.A.; Tkachenko, S.; Ding, M.; Plowright, A.T.; Engkvist, O.; Andersson, H.; Drowley, L.; Barrett, I.; Firth, M.; Akerblad, P.; et al. High-content phenotypic assay for proliferation of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes identifies L-type calcium channels as targets. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 127, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, D.; Drowley, L.; Wang, Q.-D.; Plowright, A.T.; Greber, B. Phenotypic screen identifies FOXO inhibitor to counteract maturation and promote expansion of human iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 116782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Bradley, L.A.; Farrar, E.; Bilcheck, H.O.; Tkachenko, S.; Saucerman, J.J.; Bekiranov, S.; Wolf, M.J. Inhibition of DYRK1a Enhances Cardiomyocyte Cycling After Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, F.; Günther, S.; Looso, M.; Kuenne, C.; Zhang, T.; Wiesnet, M.; Klatt, S.; Zukunft, S.; Fleming, I.; et al. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation enables heart regeneration in adult mice. Nature 2023, 622, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buikema, J.W.; Lee, S.; Goodyer, W.R.; Maas, R.G.; Chirikian, O.; Li, G.; Miao, Y.; Paige, S.L.; Lee, D.; Wu, H.; et al. Wnt Activation and Reduced Cell-Cell Contact Synergistically Induce Massive Expansion of Functional Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 50–63.e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snir, M.; Kehat, I.; Gepstein, A.; Coleman, R.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Livne, E.; Gepstein, L. Assessment of the ultrastructural and proliferative properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003, 285, H2355–H2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satin, J.; Itzhaki, I.; Rapoport, S.; Schroder, E.A.; Izu, L.; Arbel, G.; Beyar, R.; Balke, C.W.; Schiller, J.; Gepstein, L. Calcium handling in human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokhan, I.; Blum, T.S.; Campbell, S.G. Engineered heart tissue: Design considerations and the state of the art. Biophys. Rev. 2024, 5, 021308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskary, A.R.; Hudson, J.E.; Porrello, E.R. Designing multicellular cardiac tissue engineering technologies for clinical translation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 171, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliley, J.M.; Vermeer, M.C.S.C.; Duffy, R.M.; Batalov, I.; Kramer, D.; Tashman, J.W.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Lee, A.; Teplenin, A.S.; Volkers, L.; et al. Dynamic loading of human engineered heart tissue enhances contractile function and drives a desmosome-linked disease phenotype. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, D.S.; Lam, L.; Taylor, M.R.; Wang, L.; Teekakirikul, P.; Christodoulou, D.; Conner, L.; DePalma, S.R.; McDonough, B.; Sparks, E.; et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voges, H.K.; Mills, R.J.; Elliott, D.A.; Parton, R.G.; Porrello, E.R.; Hudson, J.E. Development of a human cardiac organoid injury model reveals innate regenerative potential. Development 2017, 144, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.N.; Yucel, D.; Garay, B.I.; Tolkacheva, E.G.; Kyba, M.; Perlingeiro, R.C.R.; van Berlo, J.H.; Ogle, B.M. Proliferation and Maturation: Janus and the Art of Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.J.; Titmarsh, D.M.; Koenig, X.; Parker, B.L.; Ryall, J.G.; Quaife-Ryan, G.A.; Voges, H.K.; Hodson, M.P.; Ferguson, C.; Drowley, L.; et al. Functional screening in human cardiac organoids reveals a metabolic mechanism for cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8372–E8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselbarth, R.; Esser, T.U.; Roshanbinfar, K.; Struefer, S.; Schubert, D.W.; Engel, F.B. Enhancement of engineered cardiac tissues by promotion of hiPSC-cardiomyocyte proliferation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, ehab724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, N.L.; Muskheli, V.; Razumova, M.V.; Korte, F.S.; Regnier, M.; Hauch, K.D.; Pabon, L.; Reinecke, H.; Murry, C.E. Growth of Engineered Human Myocardium With Mechanical Loading and Vascular Coculture. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, O.; Lesman, A.; Basevitch, Y.; Gepstein, A.; Arbel, G.; Habib, I.H.; Gepstein, L.; Levenberg, S. Tissue engineering of vascularized cardiac muscle from human embryonic stem cells. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, R.J.; Parker, B.L.; Quaife-Ryan, G.A.; Voges, H.K.; Needham, E.J.; Bornot, A.; Ding, M.; Andersson, H.; Polla, M.; Elliott, D.A.; et al. Drug Screening in Human PSC-Cardiac Organoids Identifies Pro-proliferative Compounds Acting via the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 895–907.E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escopete, S.; Arzt, M.; Mozneb, M.; Moses, J.; Sharma, A. Human cardiac organoids for disease modeling and drug discovery. Trends Mol. Med. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Loskill, P.; Huebsch, N.; Koo, S.; Svedlund, F.L.; Marks, N.C.; Hua, E.W.; Grigoropoulos, C.P.; Conklin, B.R.; et al. Self-organizing human cardiac microchambers mediated by geometric confinement. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, P.; Jahnel, S.M.; Papai, N.; Giesshammer, M.; Deyett, A.; Schmidt, C.; Penc, M.; Tavernini, K.; Grdseloff, N.; Meledeth, C.; et al. Cardioids reveal self-organizing principles of human cardiogenesis. Cell 2021, 184, 3299–3317 e3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakhlis, L.; Biswanath, S.; Farr, C.M.; Lupanow, V.; Teske, J.; Ritzenhoff, K.; Franke, A.; Manstein, F.; Bolesani, E.; Kempf, H.; et al. Human heart-forming organoids recapitulate early heart and foregut development. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Deyett, A.; Ilmer, T.; Haendeler, S.; Torres Caballero, A.; Novatchkova, M.; Netzer, M.A.; Ceci Ginistrelli, L.; Mancheno Juncosa, E.; Bhattacharya, T.; et al. Multi-chamber cardioids unravel human heart development and cardiac defects. Cell 2023, 186, 5587–5605.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Israeli, Y.R.; Wasserman, A.H.; Gabalski, M.A.; Volmert, B.D.; Ming, Y.; Ball, K.A.; Yang, W.; Zou, J.; Ni, G.; Pajares, N.; et al. Self-assembling human heart organoids for the modeling of cardiac development and congenital heart disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, P.; Tampakakis, E.; Jimenez, D.V.; Kannan, S.; Miyamoto, M.; Shin, H.K.; Saberi, A.; Murphy, S.; Sulistio, E.; Chelko, S.P.; et al. Precardiac organoids form two heart fields via Bmp/Wnt signaling. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auchampach, J.; Han, L.; Huang, G.N.; Kühn, B.; Lough, J.W.; O’Meara, C.C.; Payumo, A.Y.; Rosenthal, N.A.; Sucov, H.M.; Yutzey, K.E.; et al. Measuring cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activity and proliferation in the age of heart regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2022, 322, H579–H596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.L.; Shenje, L.T.; Reuter, S.; Soonpaa, M.H.; Rubart, M.; Field, L.J.; Galinanes, M. Limitations of conventional approaches to identify myocyte nuclei in histologic sections of the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010, 298, C1603–C1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpurapu, A.; Williams, H.A.; DeBenedittis, P.; Baker, C.E.; Ren, B.; Thomas, M.C.; Beard, A.J.; Devlin, G.; Harrington, J.; Parker, L.E.; et al. Deep Learning Resolved Myovascular Dynamics in the Failing Human Heart. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.R.; Nguyen, D.; Wang, B.; Jiang, S.; Sadek, H.A. Deep Learning Identifies Cardiomyocyte Nuclei With High Precision. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L.A.; Young, A.; Li, H.; Billcheck, H.O.; Wolf, M.J. Loss of Endogenously Cycling Adult Cardiomyocytes Worsens Myocardial Function. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Hippenmeyer, S.; Saadat, L.V.; Luo, L.; Weissman, I.L.; Ardehali, R. Existing cardiomyocytes generate cardiomyocytes at a low rate after birth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8850–8855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pu, W.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Huang, X.; Weng, W.; Wang, Q.D.; et al. Cell proliferation fate mapping reveals regional cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activity in subendocardial muscle of left ventricle. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, T.M.A.; Ang, Y.S.; Radzinsky, E.; Zhou, P.; Huang, Y.; Elfenbein, A.; Foley, A.; Magnitsky, S.; Srivastava, D. Regulation of Cell Cycle to Stimulate Adult Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cardiac Regeneration. Cell 2018, 173, 104–116.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereti, K.-I.; Nguyen, N.B.; Kamran, P.; Zhao, P.; Ranjbarvaziri, S.; Park, S.; Sabri, S.; Engel, J.L.; Sung, K.; Kulkarni, R.P. Analysis of cardiomyocyte clonal expansion during mouse heart development and injury. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakovic, M.; Thakkar, D.; DeBenedittis, P.; Chong, D.C.; Thomas, M.C.; Iversen, E.S.; Karra, R. Clonal Analysis of the Neonatal Mouse Heart using Nearest Neighbor Modeling. J. Vis. Exp. Jove 2020, 162, e61656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bakker, B.S.; de Jong, K.H.; Hagoort, J.; de Bree, K.; Besselink, C.T.; de Kanter, F.E.C.; Veldhuis, T.; Bais, B.; Schildmeijer, R.; Ruijter, J.M.; et al. An interactive three-dimensional digital atlas and quantitative database of human development. Science 2016, 354, aag0053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, C.F.A.; Cavoretto, P.; Csapo, B.; Falcon, O.; Nicolaides, K.H. Lung and heart volumes by three-dimensional ultrasound in normal fetuses at 12–32 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 27, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizarov, A.; Ya, J.; de Boer, B.A.; Lamers, W.H.; Christoffels, V.M.; Moorman, A.F.M. Formation of the Building Plan of the Human Heart. Circulation 2011, 123, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-P.; Li, H.-R.; Cao, X.-M.; Wang, Q.-X.; Qiao, C.-J.; Ya, J. Second heart field and the development of the outflow tract in human embryonic heart. Dev. Growth Differ. 2013, 55, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissman, N.J. Cell multiplication rates during development of the primitive cardiac tube in the chick embryo. Nature 1966, 210, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.; Meilhac, S.; Zaffran, S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, G.; Abu-Issa, R.; de Boer, B.A.; Hutson, M.R.; de Boer, P.A.; Soufan, A.T.; Ruijter, J.M.; Kirby, M.L.; van den Hoff, M.J.; Moorman, A.F. A caudal proliferating growth center contributes to both poles of the forming heart tube. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, B.A.; van den Berg, G.; de Boer, P.A.; Moorman, A.F.; Ruijter, J.M. Growth of the developing mouse heart: An interactive qualitative and quantitative 3D atlas. Dev. Biol. 2012, 368, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, E.N.; Hu, R.K.; Kern, C.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, T.Y.; Ma, Q.; Tran, S.; Zhang, B.; Carlin, D.; Monell, A.; et al. Spatially organized cellular communities form the developing human heart. Nature 2024, 627, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Samtani, R.; Dhanantwari, P.; Lee, E.; Yamada, S.; Shiota, K.; Donofrio, M.T.; Leatherbury, L.; Lo, C.W. A detailed comparison of mouse and human cardiac development. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 76, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, O.; Zdunek, S.; Felker, A.; Salehpour, M.; Alkass, K.; Bernard, S.; Sjostrom, S.L.; Szewczykowska, M.; Jackowska, T.; Dos Remedios, C.; et al. Dynamics of Cell Generation and Turnover in the Human Heart. Cell 2015, 161, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, O.; Bhardwaj, R.D.; Bernard, S.; Zdunek, S.; Barnabe-Heider, F.; Walsh, S.; Zupicich, J.; Alkass, K.; Buchholz, B.A.; Druid, H.; et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 2009, 324, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollova, M.; Bersell, K.; Walsh, S.; Savla, J.; Das, L.T.; Park, S.Y.; Silberstein, L.E.; Dos Remedios, C.G.; Graham, D.; Colan, S.; et al. Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, D.G.; Kitzman, D.W.; Hagen, P.T.; Ilstrup, D.M.; Edwards, W.D. Age-related changes in normal human hearts during the first 10 decades of life. Part I (Growth): A quantitative anatomic study of 200 specimens from subjects from birth to 19 years old. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1988, 63, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, J.A.; Margulies, K.B. Hybrid mathematical model of cardiomyocyte turnover in the adult human heart. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, C.H.; Ammanamanchi, N.; Suresh, S.; Lewarchik, C.; Rao, K.; Uys, G.M.; Han, L.; Abrial, M.; Yimlamai, D.; et al. Control of cytokinesis by beta-adrenergic receptors indicates an approach for regulating cardiomyocyte endowment. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoudary, S.R.; Fabio, A.; Yester, J.W.; Steinhauser, M.L.; Christopher, A.B.; Gyngard, F.; Adams, P.S.; Morell, V.O.; Viegas, M.; Da Silva, J.P.; et al. Design and rationale of a clinical trial to increase cardiomyocyte division in infants with tetralogy of Fallot. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 339, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.; Bhushan, S.; Fan, Q.; Tang, M. Midterm outcome after surgical correction of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiary, F.; Mohr, F.W.; Kostelka, M. Midterm outcome after surgical correction of anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2011, 2, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, C.B.; Balzer, D.T.; Mendeloff, E.N. Repair of anomalous left main coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery in infants: Long-term impact on the mitral valve. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001, 71, 1985–1988; discussion 1988–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubner, B.J.; Schneider, J.; Schweigmann, U.; Schuetz, T.; Dichtl, W.; Velik-Salchner, C.; Stein, J.I.; Penninger, J.M. Functional Recovery of a Human Neonatal Heart After Severe Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhoff, D.; Topkara, V.K.; Sayer, G.; Uriel, N. Reverse Remodeling With Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1594–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, E.; Rame, J.E.; Yin, M.; Patel, S.R.; Lowes, B.; Selzman, C.; Trivedi, J.; Laughter, M.; Atluri, P.; Goldstein, D.; et al. Long Term Post Explant Outcomes from RESTAGE-HF: A Prospective Multi-Center Study of Myocardial Recovery Using LVADs. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2021, 40, S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, C.; Mandawat, A.; Sun, J.L.; Triana, T.; Chiswell, K.; Karra, R. Recovery of left ventricular function is associated with improved outcomes in LVAD recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canseco, D.C.; Kimura, W.; Garg, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Abdisalaam, S.; Das, S.; Asaithamby, A.; Mammen, P.P.; Sadek, H.A. Human ventricular unloading induces cardiomyocyte proliferation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, W.; Rode, J.; Collin, S.; Rost, F.; Heinke, P.; Hariharan, A.; Pickel, L.; Simonova, I.; Lázár, E.; Graham, E.; et al. A Latent Cardiomyocyte Regeneration Potential in Human Heart Disease. Circulation 2025, 151, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pana, T.A.; Savla, J.; Kepinski, I.; Fairbourn, A.; Afzal, A.; Mammen, P.; Drazner, M.; Subramaniam, R.M.; Xing, C.; Morton, K.A.; et al. Bidirectional Changes in Myocardial 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake After Human Ventricular Unloading. Circulation 2022, 145, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Skali, H.; Rivero, J.; Campbell, P.; Griffin, L.; Smith, C.; Foster, C.; Claggett, B.; Glynn, R.J.; Couper, G. Assessment of myocardial viability and left ventricular function in patients supported by a left ventricular assist device. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2014, 33, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakos, N.A. Ventricular assist device implantation corrects myocardial metabolic derangements in advanced heart failure. Circulation 2014, 125, 2844–2853. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.L.; Fermin, D.R.; Birks, E.J.; Barton, P.J.; Slaughter, M.; Eckman, P.; Baba, H.A.; Wohlschlaeger, J.; Miller, L.W. Clinical, molecular, and genomic changes in response to a left ventricular assist device. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogletree, M.L. Duration of left ventricular assist device support: Effects on abnormal calcium handling in heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010, 29, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eulalio, A.; Mano, M.; Dal Ferro, M.; Zentilin, L.; Sinagra, G.; Zacchigna, S.; Giacca, M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature 2012, 492, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacak, C.A.; Mah, C.S.; Thattaliyath, B.D.; Conlon, T.J.; Lewis, M.A.; Cloutier, D.E.; Zolotukhin, I.; Tarantal, A.F.; Byrne, B.J. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 9 Leads to Preferential Cardiac Transduction In Vivo. Circ. Res. 2006, 99, e3–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesizza, P.; Prosdocimo, G.; Martinelli, V.; Sinagra, G.; Zacchigna, S.; Giacca, M. Single-Dose Intracardiac Injection of Pro-Regenerative MicroRNAs Improves Cardiac Function After Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrini, C.; Cubero, R.J.; Dirkx, E.; Braga, L.; Ali, H.; Prosdocimo, G.; Gutierrez, M.I.; Collesi, C.; Licastro, D.; Zentilin, L.; et al. Common Regulatory Pathways Mediate Activity of MicroRNAs Inducing Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 2759–2771.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heqet Therapeutics. Pipeline. Available online: https://www.heqettherapeutics.com/pipeline/ (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Abouleisa, R.R.E.; Salama, A.B.M.; Ou, Q.; Tang, X.-L.; Solanki, M.; Guo, Y.; Nong, Y.; McNally, L.; Lorkiewicz, P.K.; Kassem, K.M.; et al. Transient Cell Cycle Induction in Cardiomyocytes to Treat Subacute Ischemic Heart Failure. Circulation 2022, 145, 1339–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therapeutics Tenaya. Our Programs: Pipeline. Available online: https://www.tenayatherapeutics.com/our-programs/#pipeline (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Bassat, E.; Mutlak, Y.E.; Genzelinakh, A.; Shadrin, I.Y.; Umansky, K.B.; Yifa, O.; Kain, D.; Rajchman, D.; Leach, J.; Bassat, D.R. The extracellular matrix protein agrin promotes heart regeneration in mice. Nature 2017, 547, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Elkahal, J.; Wang, T.; Rimmer, R.; Genzelinakh, A.; Bassat, E.; Wang, J.; Perez, D.; Kain, D.; Lendengolts, D.; et al. Egr1 regulates regenerative senescence and cardiac repair. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VelaKOR Bio. Available online: https://www.velakorbio.com/ (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Marin-Juez, R.; Marass, M.; Gauvrit, S.; Rossi, A.; Lai, S.L.; Materna, S.C.; Black, B.L.; Stainier, D.Y. Fast revascularization of the injured area is essential to support zebrafish heart regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11237–11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Juez, R.; El-Sammak, H.; Helker, C.S.M.; Kamezaki, A.; Mullapuli, S.T.; Bibli, S.I.; Foglia, M.J.; Fleming, I.; Poss, K.D.; Stainier, D.Y.R. Coronary Revascularization During Heart Regeneration Is Regulated by Epicardial and Endocardial Cues and Forms a Scaffold for Cardiomyocyte Repopulation. Dev. Cell 2019, 51, 503–515.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Goldstone, A.B.; Wang, H.; Farry, J.; D’Amato, G.; Paulsen, M.J.; Eskandari, A.; Hironaka, C.E.; Phansalkar, R.; Sharma, B.; et al. A Unique Collateral Artery Development Program Promotes Neonatal Heart Regeneration. Cell 2019, 176, 1128–1142.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, J.; Nixon, A.B.; Daubert, M.A.; Yow, E.; Januzzi, J.; Fiuzat, M.; Whellan, D.J.; O’Connor, C.M.; Ezekowitz, J.; Pina, I.L.; et al. Circulating Angiokines Are Associated With Reverse Remodeling and Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimeh, Z.; Loughran, J.; Birks, E.J.; Bolli, R. Vascular endothelial growth factor in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacca, M.; Zacchigna, S. VEGF gene therapy: Therapeutic angiogenesis in the clinic and beyond. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangi, L.; Lui, K.O.; von Gise, A.; Ma, Q.; Ebina, W.; Ptaszek, L.M.; Spater, D.; Xu, H.; Tabebordbar, M.; Gorbatov, R.; et al. Modified mRNA directs the fate of heart progenitor cells and induces vascular regeneration after myocardial infarction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.; Clarke, J.C.; Yen, C.; Gregoire, F.; Albery, T.; Billger, M.; Egnell, A.-C.; Gan, L.-M.; Jennbacken, K.; Johansson, E. Biocompatible, purified VEGF-A mRNA improves cardiac function after intracardiac injection 1 week post-myocardial infarction in swine. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 9, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttila, V.; Saraste, A.; Knuuti, J.; Hedman, M.; Jaakkola, P.; Laugwitz, K.L.; Krane, M.; Jeppsson, A.; Sillanmaki, S.; Rosenmeier, J.; et al. Direct intramyocardial injection of VEGF mRNA in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttila, V.; Saraste, A.; Knuuti, J.; Jaakkola, P.; Hedman, M.; Svedlund, S.; Lagerstrom-Fermer, M.; Kjaer, M.; Jeppsson, A.; Gan, L.M. Synthetic mRNA Encoding VEGF-A in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Design of a Phase 2a Clinical Trial. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.F.; Simon, H.; Chen, H.; Bates, B.; Hung, M.C.; Hauser, C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature 1995, 378, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, M.; Casagranda, F.; Orioli, D.; Simon, H.; Lai, C.; Klein, R.; Lemke, G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature 1995, 378, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersell, K.; Arab, S.; Haring, B.; Kuhn, B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell 2009, 138, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Yin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, L.; Liu, J. ErbB2 is required for cardiomyocyte proliferation in murine neonatal hearts. Gene 2016, 592, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, B.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Xin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y. Neuregulin-1 suppresses cardiomyocyte apoptosis by activating PI3K/Akt and inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2012, 370, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedhli, N.; Huang, Q.; Kalinowski, A.; Palmeri, M.; Hu, X.; Russell, R.R.; Russell, K.S. Endothelium-derived neuregulin protects the heart against ischemic injury. Circulation 2011, 123, 2254–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan, D.J.; Anderson, S.A.; Lenneman, C.G.; Brittain, E.; Muldowney, J.A.S., 3rd; Mendes, L.; Zhao, P.Z.; Iaci, J.; Frohwein, S.; Zolty, R.; et al. A Phase I, Single Ascending Dose Study of Cimaglermin Alfa (Neuregulin 1beta3) in Patients With Systolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2016, 1, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Steiner, J.; Kassi, M.; Wheeler, M.T.; Spahillari, A.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Grodin, J.L.; Solomon, N.; Singhal, S.; McEwen, A.M.G.; et al. Single Ascending-Dose Study of Selective ErbB4 Agonist JK07 in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2025, 10, 101352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heallen, T.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Bonilla-Claudio, M.; Klysik, E.; Johnson, R.L.; Martin, J.F. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science 2011, 332, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gise, A.; Lin, Z.; Schlegelmilch, K.; Honor, L.B.; Pan, G.M.; Buck, J.N.; Ma, Q.; Ishiwata, T.; Zhou, B.; Camargo, F.D. YAP1, the nuclear target of Hippo signaling, stimulates heart growth through cardiomyocyte proliferation but not hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2394–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Kim, Y.; Sutherland, L.B.; Qi, X.; McAnally, J.; Schwartz, R.J.; Richardson, J.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor signaling by Yap governs cardiomyocyte proliferation and embryonic heart size. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, ra70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, J.P.; Heallen, T.; Zhang, M.; Rahmani, M.; Morikawa, Y.; Hill, M.C.; Segura, A.; Willerson, J.T.; Martin, J.F. Hippo pathway deficiency reverses systolic heart failure after infarction. Nature 2017, 550, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heallen, T.; Morikawa, Y.; Leach, J.; Tao, G.; Willerson, J.T.; Johnson, R.L.; Martin, J.F. Hippo signaling impedes adult heart regeneration. Development 2013, 140, 4683–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; von Gise, A.; Zhou, P.; Gu, F.; Ma, Q.; Jiang, J.; Yau, A.L.; Buck, J.N.; Gouin, K.A.; van Gorp, P.R. Cardiac-specific YAP activation improves cardiac function and survival in an experimental murine MI model. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroe, T.O.; Hill, M.C.; Morikawa, Y.; Leach, J.P.; Heallen, T.; Cao, S.; Krijger, P.H.L.; de Laat, W.; Wehrens, X.H.T.; Rodney, G.G.; et al. YAP Partially Reprograms Chromatin Accessibility to Directly Induce Adult Cardiogenesis In Vivo. Dev. Cell 2019, 48, 765–779.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Li, R.G.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Deshmukh, V.; Hill, M.C.; Martin, J.F. YAP Overcomes Mechanical Barriers to Induce Mitotic Rounding and Adult Cardiomyocyte Division. Circulation 2025, 151, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study Record: NCT06831825. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06831825 (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Martin Heart Lab. YAP101 Passes First Safety Milestone in Clinical Trial. Available online: https://www.jfmartinlab.com/blog/yap101-passes-first-safety-milestone-in-clinical-trial (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Nguyen, P.D.; Gooijers, I.; Campostrini, G.; Verkerk, A.O.; Honkoop, H.; Bouwman, M.; de Bakker, D.E.M.; Koopmans, T.; Vink, A.; Lamers, G.E.M.; et al. Interplay between calcium and sarcomeres directs cardiomyocyte maturation during regeneration. Science 2023, 380, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Neidig, L.E.; Yang, X.; Weber, G.J.; El-Nachef, D.; Tsuchida, H.; Dupras, S.; Kalucki, F.A.; Jayabalu, A.; Futakuchi-Tsuchida, A.; et al. Pharmacologic therapy for engraftment arrhythmia induced by transplantation of human cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 2473–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadum, A.; Singh, N.; Kurian, A.A.; Munir, I.; Mehmood, T.; Brown, K.; Sharkar, M.T.K.; Chepurko, E.; Sassi, Y.; Oh, J.G.; et al. Pkm2 Regulates Cardiomyocyte Cell Cycle and Promotes Cardiac Regeneration. Circulation 2020, 141, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadum, A.; Kurian, A.A.; Chepurko, E.; Sassi, Y.; Hajjar, R.J.; Zangi, L. Specific Modified mRNA Translation System. Circulation 2020, 142, 2485–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wu, Y.; Adjmi, M.; Matthews, R.C.; Kurian, A.A.; Zak, M.M.; Yoo, J.; Mainkar, G.; Lawless, H.; Lu, Y.A.; et al. Transient overexpression of hPKM2 in porcine cardiomyocytes prevents heart failure after myocardial infarction. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, J.A.; Kuzu, G.; Lee, N.; Karasik, J.; Gemberling, M.; Foglia, M.J.; Karra, R.; Dickson, A.L.; Sun, F.; Tolstorukov, M.Y.; et al. Resolving Heart Regeneration by Replacement Histone Profiling. Dev. Cell 2017, 40, 392–404 e395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Cigliola, V.; Oonk, K.A.; Petrover, Z.; DeLuca, S.; Wolfson, D.W.; Vekstein, A.; Mendiola, M.A.; Devlin, G.; Bishawi, M.; et al. An enhancer-based gene-therapy strategy for spatiotemporal control of cargoes during tissue repair. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 96–111 e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Steimle, J.D.; Straight, E.; Li, R.G.; Morikawa, Y.; Iqbal, Z.; Xie, B.; Wang, J.; Paltzer, W.G.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Gene therapy CM-YAPon protects the mouse heart from myocardial infarction. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 4, 1616–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bish, L.T.; Morine, K.; Sleeper, M.M.; Sanmiguel, J.; Wu, D.; Gao, G.; Wilson, J.M.; Sweeney, H.L. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 provides global cardiac gene transfer superior to AAV1, AAV6, AAV7, and AAV8 in the mouse and rat. Hum. Gene Ther. 2008, 19, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.J.; Simon, K.E.; Blondel, L.O.; Fanous, M.M.; Roger, A.L.; Maysonet, M.S.; Devlin, G.W.; Smith, T.J.; Oh, D.K.; Havlik, L.P.; et al. Cross-species evolution of a highly potent AAV variant for therapeutic gene transfer and genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeissler, D.; Busch, M.; Grieskamp, S.; Meinhardt, E.; Wurzer, H.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Schrattel, A.K.; Molter, S.; Kehr, D.; Qatato, M.; et al. Novel Human Heart-Derived Natural Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Combines Cardiospecificity With Cardiotropism In Vivo. Circulation 2025, 152, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabebordbar, M.; Lagerborg, K.A.; Stanton, A.; King, E.M.; Ye, S.; Tellez, L.; Krunnfusz, A.; Tavakoli, S.; Widrick, J.J.; Messemer, K.A.; et al. Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Cell 2021, 184, 4919–4938.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.J.; Flanigan, K.M.; Matesanz, S.E.; Finkel, R.S.; Waldrop, M.A.; D’Ambrosio, E.S.; Johnson, N.E.; Smith, B.K.; Bönnemann, C.; Carrig, S.; et al. Current clinical applications of AAV-mediated gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 2479–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvaev, V.V.; Tam, Y.K.; Lee, B.W.; Myerson, J.W.; Herbst, A.; Kiseleva, R.Y.; Glassman, P.M.; Parhiz, H.; Alameh, M.G.; Pardi, N.; et al. Systemic delivery of biotherapeutic RNA to the myocardium transiently modulates cardiac contractility in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2409266122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

McLane, R.D.; Cheruku, A.; Williams, A.B.; Karra, R. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential of Human Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13020074

McLane RD, Cheruku A, Williams AB, Karra R. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential of Human Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(2):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13020074

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcLane, Richard D., Abhay Cheruku, Ashley B. Williams, and Ravi Karra. 2026. "Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential of Human Cardiomyocyte Proliferation" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 2: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13020074

APA StyleMcLane, R. D., Cheruku, A., Williams, A. B., & Karra, R. (2026). Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential of Human Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(2), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13020074