Unveiling the Hidden Risk: Ticagrelor-Induced Bradyarrhythmias and Conduction Complications in ACS Patients—Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Case Presentation

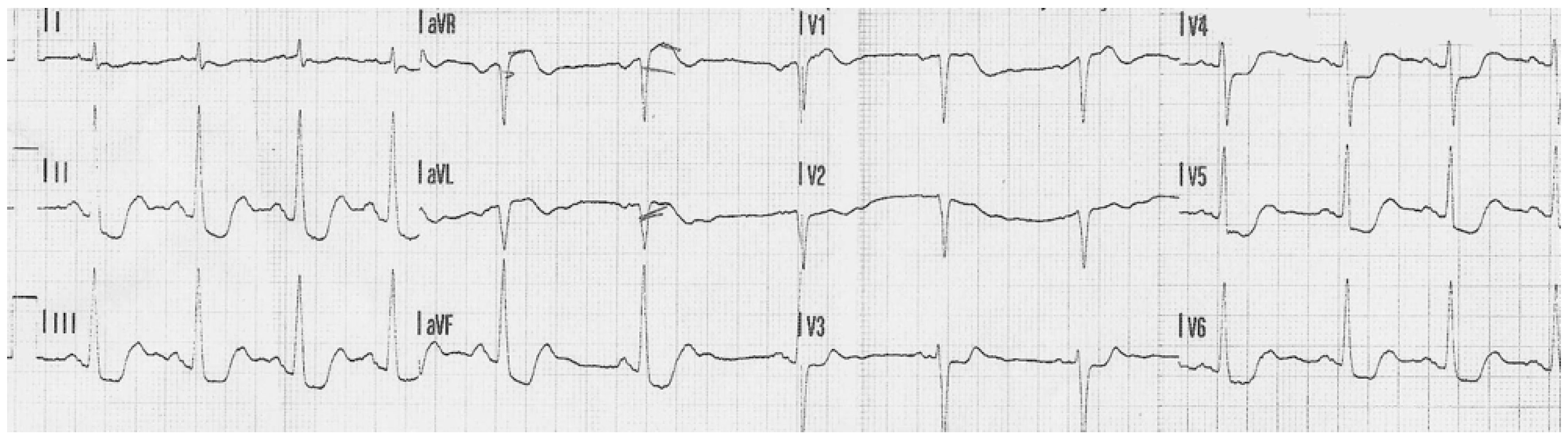

3.1. Case 1

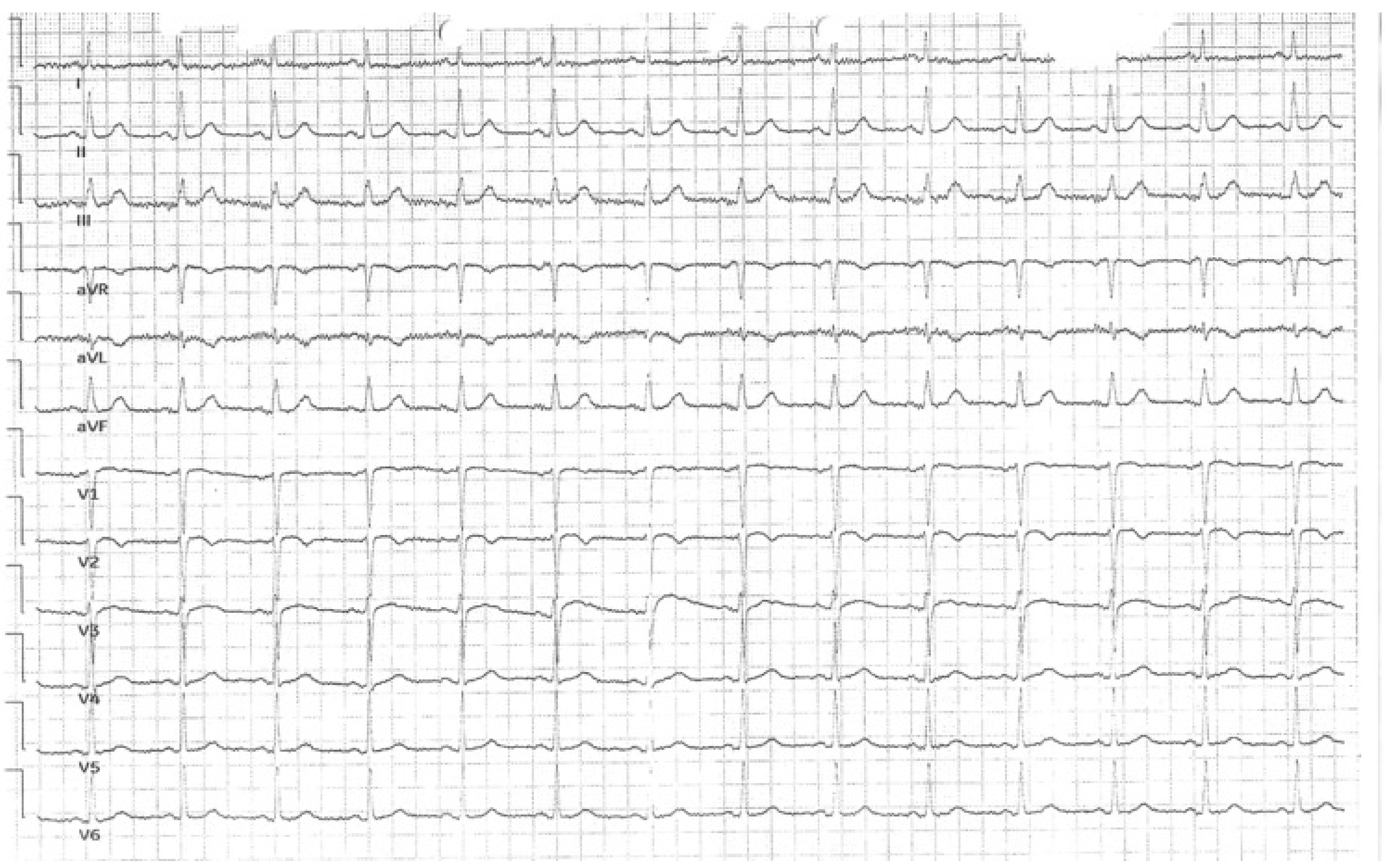

3.2. Case 2

4. Discussion

4.1. Ticagrelor—Principal Mechanism of Action

4.2. Adverse Reactions to Ticagrelor

4.3. Management of Ticagrelor-Induced Pauses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Low, A.; Leong, K.; Sharma, A.; Oqueli, E. Ticagrelor-associated ventricular pauses: A case report and literature review. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2018, 3, yty156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.; Wiseman, K.; Udongwo, N.; Ajam, F.; Hansalia, R.; Apolito, R. Heart block caused by ticagrelor use in a patient who underwent adenosine diastolic fractional reserve assessment: A case report. J. Med. Cases 2021, 12, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, S.; Van Giezen, J.J.J. Ticagrelor: The first reversibly binding oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2009, 27, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buske, M.; Feistritzer, H.J.; Jobs, A.; Thiele, H. Management of acute coronary syndrome: ESC guidelines 2023. Herz 2024, 49, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirica, B.M.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Michelson, E.L.; Harrington, R.A.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; Pais, P.; Raev, D.; et al. Incidence of bradyarrhythmias and clinical bradyarrhythmic events in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel in the PLATO trial: Results of the continuous electrocardiographic assessment substudy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, P.; Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Cao, B. Progress in the clinical effects and adverse reactions of ticagrelor. Thromb. J. 2024, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylander, S.; Femia, E.A.; Scavone, M.; Berntsson, P.; Asztély, A.K.; Nelander, K.; Löfgren, L.; Nilsson, R.G.; Cattaneo, M. Ticagrelor inhibits human platelet aggregation via adenosine in addition to P2Y12 antagonism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, N.T.; Shah, A.; Khan, M.; Jaiswal, V.; Mattumpuram, J. A case of ticagrelor-induced sinus pause. Cureus 2023, 15, e42791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakowiak, A.; Kuleta, J.; Plech, I.; Zarębiński, M.; Wojciechowska, M.; Wretowski, D.; Cudnoch-Jędrzejewska, A. Ticagrelor-related severe dyspnoea: Mechanisms, characteristic features, differential diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Med. Insights Case Rep. 2020, 13, 1179547620956634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Silverstein, B.V.; Jansen, M.; Bray, C.L.; Lee, A.C. Sinoatrial arrest caused by ticagrelor after angioplasty in a 62-year-old woman with acute coronary syndrome. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2019, 46, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk, H.U.H.; Escobar, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Bates, E.R.; Khalid, U.; Jneid, H.; Birnbaum, Y.; Levine, G.N.; Smith, S.C.; Krittanawong, C. Dual antiplatelet therapy: A concise review for clinicians. Life 2023, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, M.; Deblaise, J.; Choussat, R.; Dubourg, O.; Mansencal, N. Side effects of ticagrelor: Sinus node dysfunction with ventricular pause. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 191, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, E.; Borghi, A.; Modonesi, L.; Cappelli, S. Ticagrelor therapy and atrioventricular block: Do we need to worry? World J. Clin. Cases 2017, 5, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarini, D.; Muraca, I.; Berteotti, M.; Gori, A.M.; Sorrentino, A.; Bertelli, A.; Marcucci, R.; Valenti, R. Pathophysiological and molecular basis of the side effects of ticagrelor: Lessons from a case report. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobesh, P.P.; Oestreich, J.H. Ticagrelor: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical efficacy, and safety. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Doe, A.; Brown, R. Arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction: Incidence and management. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 31, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, A.; Patel, M. Study of bradyarrhythmias in acute myocardial infarction patients and clinical implications. Eur. J. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 14, 420–428. [Google Scholar]

- Arioti, M.; Sirianni, G.; Laudisa, M.L.; De Cesare, N.B. A rare but serious complication of ticagrelor therapy: A case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2020, 4, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahhal, A.; Aljundi, A.; Ibrahim Mohamed, S.S.; Arif, M.A.; Arabi, A.R. Prolonged ventricular pause associated with ticagrelor use: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e05017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, D.A.N. Ticagrelor-associated heart block: The need for close and continued monitoring. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2017, 2017, 5074891. [Google Scholar]

- Brignole, M.; Moya, A.; De Lange, F.J.; Deharo, J.C.; Elliott, P.M.; Fanciulli, A.; Fedorowski, A.; Furlan, R.; Kenny, R.A.; Martín, A.; et al. 2018 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1883–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Laboratory Parameter | Reference Range | Hospitalization |

|---|---|---|

| Red Blood Cells (T/L) | 3.85–5.2 | 4.56 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.8–15.8 | 14.2 |

| Platelets (G/L) | 160.0–370.0 | 279.0 |

| White Blood Cells (G/L) | 3.6–10.5 | 16.86 |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein (mg/dL) | <55 | 280 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 136–145 | 128 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.5–5.1 | 3.1 |

| Ultrasensitive troponin I (µg/L) | <0.0156 | 0.1770 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.50–1.20 | 0.97 |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (mlU/L) | 0.35–4.94 | 2.24 |

| N-terminal pro B-type Natriuretic Peptide (pg/mL) | <125.00 | 733.20 |

| Laboratory Parameter | Reference Range | Hospitalization |

|---|---|---|

| Red Blood Cells (T/L) | 4.0–5.65 | 5.13 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.5–17.2 | 15.6 |

| Platelets (G/L) | 160.0–370.0 | 211.0 |

| White Blood Cells (G/L) | 3.6–10.5 | 10.0 |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein (mg/dL) | <55 | 145 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 136–145 | 137 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.5–5.1 | 4.1 |

| Ultrasensitive troponin I (µg/L) | <0.0342 | 13.8980 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.70–1.30 | 0.70 |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (mg/dL) | 0.35–4.94 | 1.05 |

| Cause | Estimated Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Ischemia of infarction of conduction system (e.g., AV node, His bundle) | 30–40% |

| Increased vagal tone (especially in inferior MI) | 15–25% |

| Electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hyperkalemia) | 5–10% |

| Use of AV nodal blocking drugs (e.g., beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin) | 10–20% |

| Reperfusion injury (e.g., transient AV block after PCI) | 5–10% |

| Age-related degeneration (fibrosis of conduction system) | 5–10% |

| Ticagrelor-induced sinus pauses | <6% |

| Hypothyroidism | <2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gorzynska-Schulz, A.; Stencelewski, D.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L.; Lica-Gorzynska, M.; Firkowska, A.; Wabich, E. Unveiling the Hidden Risk: Ticagrelor-Induced Bradyarrhythmias and Conduction Complications in ACS Patients—Case Series. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010007

Gorzynska-Schulz A, Stencelewski D, Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz L, Lica-Gorzynska M, Firkowska A, Wabich E. Unveiling the Hidden Risk: Ticagrelor-Induced Bradyarrhythmias and Conduction Complications in ACS Patients—Case Series. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorzynska-Schulz, Aleksandra, Damian Stencelewski, Ludmiła Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, Monika Lica-Gorzynska, Agata Firkowska, and Elżbieta Wabich. 2026. "Unveiling the Hidden Risk: Ticagrelor-Induced Bradyarrhythmias and Conduction Complications in ACS Patients—Case Series" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010007

APA StyleGorzynska-Schulz, A., Stencelewski, D., Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L., Lica-Gorzynska, M., Firkowska, A., & Wabich, E. (2026). Unveiling the Hidden Risk: Ticagrelor-Induced Bradyarrhythmias and Conduction Complications in ACS Patients—Case Series. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010007