Clinical Outcomes After Immediate Coronary Angiography in Elderly Versus Younger Patients Suffering from Acute Coronary Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Admission with ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA).

- Underwent coronary angiography within 6 h of admission.

- Age ≥ 18 years.

- ▪

- No ACS diagnosis.

- ▪

- Killip class IV at admission.

- ▪

- Requirement for mechanical circulatory support (intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella micro-axial pump), and/or mechanical ventilation.

- ▪

- Significant valvular disease or prior valve surgery.

- ▪

- Major in-hospital bleeding requiring surgery or transfusion.

- ▪

- Anticipated life expectancy < 1 year due to non-cardiac conditions.

- ▪

- Vital status,

- ▪

- Ischemic events (MI, CVI, repeat PCI),

- ▪

- Hospitalizations for cardiac causes,

- ▪

- Adherence to antiplatelet therapy.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Damluji, A.A.; Forman, D.E.; Wang, T.Y.; Chikwe, J.; Kunadian, V.; Rich, M.W.; Young, B.A.; Page, R.L., 2nd; DeVon, H.A.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Older Adult Population: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e32–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826, Erratum in: Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 148, e9–e119, Erratum in: Circulation 2023, 148, e148; Erratum in: Circulation 2023, 148, e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillinger, J.G.; Laine, M.; Bouajila, S.; Paganelli, F.; Henry, P.; Bonello, L. Antithrombotic strategies in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Arch. Cardiovasc Dis. 2021, 114, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, P.; Mehran, R.; Colleran, R.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Byrne, R.A.; Capodanno, D.; Cuisset, T.; Cutlip, D.; Eerdmans, P.; Eikelboom, J.; et al. Defining high bleeding risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A consensus document from the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2632–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehilli, J.; Presbitero, P. Coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome in women. Heart 2020, 106, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, W.T.; Khan, M.R.; Deshotels, M.R.; Jneid, H. Challenges and Controversies in the Management of ACS in Elderly Patients. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, C.B. Predictors of Hospital Mortality in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulvenstam, A.; Graipe, A.; Irewall, A.L.; Söderström, L.; Mooe, T. Incidence and predictors of cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome in a population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.N.; Pocock, S.; Kaul, P.; Owen, R.; Goodman, S.G.; Granger, C.B.; Nicolau, J.C.; Simon, T.; Westermann, D.; Yasuda, S.; et al. Comparing the long-term outcomes in chronic coronary syndrome patients with prior ST-segment and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Findings from the TIGRIS registry. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihatov, N.; Mosarla, R.C.; Kirtane, A.J.; Parikh, S.A.; Rosenfield, K.; Chen, S.; Secemsky, E.A. Outcomes Associated with Peripheral Artery Disease in Myocardial Infarction with Cardiogenic Shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotanidis, C.P.; Mills, G.B.; Bendz, B.; Berg, E.S.; Hildick-Smith, D.; Hirlekar, G.; Milasinovic, D.; Morici, N.; Myat, A.; Tegn, N.; et al. Invasive vs. conservative management of older patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wyk, G.W.; Berkovsky, S.; Fraile Navarro, D.; Coiera, E. Comparing health outcomes between coronary interventions in frail patients aged 75 years or older with acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, G.; Chen, X.H.; Li, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.K.; Gong, W.; Yan, Y.; Nie, S.P.; Henriques, J.P. Effect of complete revascularization in acute coronary syndrome after 75 years old: Insights from the BleeMACS registry. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rout, A.; Moumneh, M.B.; Kalra, K.; Singh, S.; Garg, A.; Kunadian, V.; Biscaglia, S.; Alkhouli, M.A.; Rymer, J.A.; Batchelor, W.B.; et al. Invasive Versus Conservative Strategy in Older Adults ≥75 Years of Age With Non-ST-segment-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e036151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampka, Z.; Drabczyk, M.; Żak, M.; Mizia-Stec, K.; Wybraniec, M.T. Prognostic significance of small vessel coronary artery disease in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with percutaneous coronary interventions. Postep. Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2023, 19, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xing, Y.L.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Miao, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, K.; Li, H.W.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H. Invasive treatment strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 12, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quintana, H.K.; Janszky, I.; Kanar, A.; Gigante, B.; Druid, H.; Ahlbom, A.; de Faire, U.; Hallqvist, J.; Leander, K. Comorbidities in relation to fatality of first myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2018, 32, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kureshi, F.; Shafiq, A.; Arnold, S.V.; Gosch, K.; Breeding, T.; Kumar, A.S.; Jones, P.G.; Spertus, J.A. The prevalence and management of angina among patients with chronic coronary artery disease across US outpatient cardiology practices: Insights from the Angina Prevalence and Provider Evaluation of Angina Relief (APPEAR) study. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, H.B.; Arsanjani, R.; Sung, J.M.; Heo, R.; Lee, B.K.; Lin, F.Y.; Hadamitzky, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Conte, E.; Andreini, D.; et al. Impact of statins based on high-risk plaque features on coronary plaque progression in mild stenosis lesions: Results from the PARADIGM study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 24, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, M.T.; Armstrong, P.W.; Fox, K.A.; White, H.D.; Prabhakaran, D.; Goodman, S.G.; Cornel, J.H.; Bhatt, D.L.; Clemmensen, P.; TRILOGY ACS Investigators; et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes without revascularization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadafora, L.; Betti, M.; D’Ascenzo, F.; De Ferrari, G.; De Filippo, O.; Gaudio, C.; Collet, C.; Sabouret, P.; Agostoni, P.; Zivelonghi, C.; et al. Impact of In-Hospital Bleeding on Postdischarge Therapies and Prognosis in Acute Coronary Syndromes. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 85, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, J.S.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Bischoff, J.M.; Bittl, J.A.; Cohen, M.G.; DiMaio, J.M.; Don, C.W.; et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e4–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savonitto, S.; Ferri, L.A.; Piatti, L.; Grosseto, D.; Piovaccari, G.; Morici, N.; Bossi, I.; Sganzerla, P.; Tortorella, G.; Cacucci, M.; et al. Comparison of Reduced-Dose Prasugrel and Standard-Dose Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Early Percutaneous Revascularization. Circulation 2018, 137, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szummer, K.; Montez-Rath, M.E.; Alfredsson, J.; Erlinge, D.; Lindahl, B.; Hofmann, R.; Ravn-Fischer, A.; Svensson, P.; Jernberg, T. Comparison Between Ticagrelor and Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients with an Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation 2020, 142, 1700–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; de Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Tjon Joe Gin, M.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | O75 n = 203 | Y75 n = 1643 | OR [95%CI] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 80 ± 4 | 59 ± 9 | ----- | |

| Male n (%) | 110 (54) | 1003 (61) | 0.758 [0.546–1.478] | 0.256 |

| Heredity n (%) | 42 (21) | 624 (38) | 0.426 [0.299–0.607] | <0.001 |

| Hypertension n (%) | 162 (80) | 1199 (73) | 1.462 [1.020–2.094] | 0.037 |

| Diabetes mellitus n (%) | 55 (27) | 328 (20) | 1.490 [1.069–2.077] | 0.022 |

| Insulin-dependent DM (%) | 16 (8) | 164 (10) | 0.946 [0.754–1.120] | 0.321 |

| Dyslipidemia n (%) | 88 (43) | 644 (39) | 1.188 [0.885–1.596] | 0.254 |

| PAD n (%) | 19 (9) | 68 (4) | 2.392 [1.407–4.070] | <0.001 |

| Smoking n (%) | 36 (18) | 793 (48) | 0.514 [0.209–0.734] | <0.001 |

| Previous MI n (%) | 42 (21) | 341 (21) | 1.915 [0.787–1.189] | 0.940 |

| Previous CVI n (%) | 20 (10) | 93 (6) | 1.821 [1.097–3.024] | 0.019 |

| Previous PCI n (%) | 30 (15) | 206 (12) | 1.076 [0.742–1.965] | 0.631 |

| Previous CABG n (%) | 14 (7) | 57 (3) | 1.045 [0.850–1.745] | 0.054 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 ± 4 | 28 ± 7 | 2.549 [1.473–3.626] | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 36 ± 10 | 41 ± 14 | 4.275 [2.138–6.413] | <0.001 |

| Variable | O75 n = 1643 | Y75 n = 203 | OR [95%CI] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable angina n (%) | 8 (4) | 81 (5) | 0.792 [0.377–1.662] | 0.256 |

| STEMI n (%) | 168 (83) | 1358 (83) | 1.007 [0.684–1.481] | 0.256 |

| NSTEMI n (%) | 24 (12) | 180 (11) | 1.091 [0.693–1.716] | 0.256 |

| CABG during hosp. n (%) | 2 (1) | 10 (0.6) | 1.626 [0.354–7.473] | 0.256 |

| No treatment n (%) | 28 (14) | 258 (16) | 0.860 [0.564–1.309] | 0.256 |

| Days in hospital (days) | 4 ± 8 | 3 ± 3 | 1.248 [0.692–1.805] | 0.256 |

| Maximum hs troponin (ng) | 49,469 ± 63,934 | 49,874 ± 77,997 | −454 [−11,911–11,001] | 0.256 |

| Death during hosp. n (%) | 9 (4.4) | 10 (0.6) | 7.580 [3.043–18.884] | <0.001 |

| Variable | O75 n = 1643 | Y75 n = 203 | OR [95%CI] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVD n (%) | 114 (56) | 727 (44) | 1.854 [1.106–3.458] | 0.004 |

| * Vessels treated | ||||

| LAD n (%) | 105 (52) | 684 (41) | 1.500 [1.120–2.009] | 0.006 |

| Cx n (%) | 71 (35) | 457 (28) | 1.056 [0.754–1.743] | 0.099 |

| RCA n (%) | 97 (48) | 699 (42) | 1.237 [0.924–1.657] | 0.155 |

| SVG n (%) | 7 (3) | 33 (2) | 1.744 [0.761–3.994] | 0.184 |

| Radial access n (%) | 148 (73) | 1417 (86) | 0.429 [0.305–0.602] | < 0.001 |

| Multivessel PCI n (%) | 37 (18) | 280 (17) | 1.086 [0.743–1.586] | 0.673 |

| LM PCI n (%) (ng) | 12 (6) | 49 (3) | 2.044 [1.068–3.911] | 0.028 |

| Bifurcation PCI n (%) | 151 (12) | 203 (12) | 0.991 [0.636–1.545] | 0.987 |

| More than one stent n (%) | 77 (38) | 616 (37) | 1.087 [0.879–1.245] | 0.942 |

| Stent diameter < 3.0 mm n (%) | 72 (35) | 448 (27) | 1.426 [1.007–1.843] | 0.031 |

| Variable | O75 n = 1643 | Y75 n = 203 | OR [95% CI] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

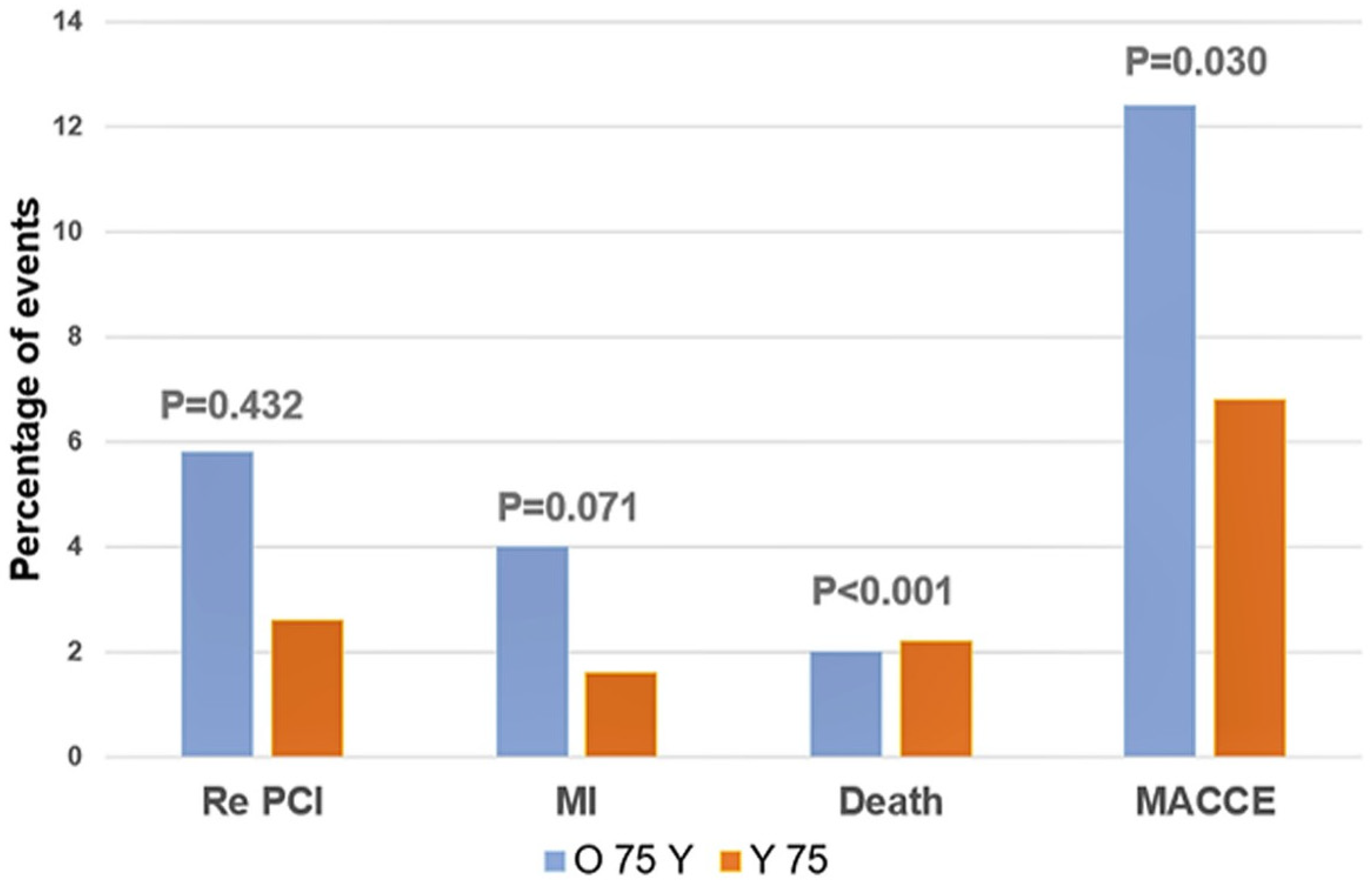

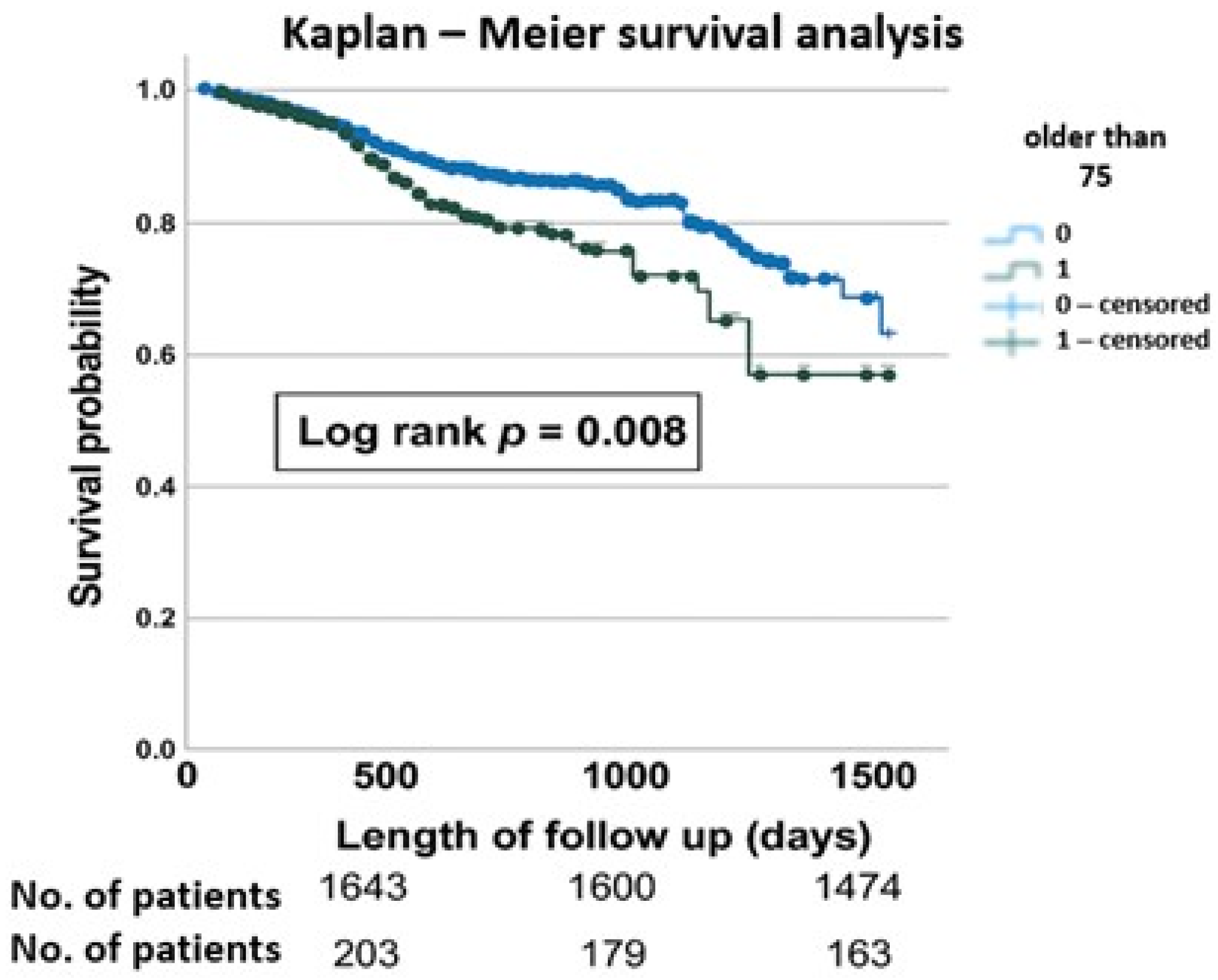

| Death n (%) | 14 (6.9) | 27 (1.6) | 4.436 [2.286–8.608] | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction n (%) | 11 (5.4) | 54 (3.3) | 0.502 [0.067–3.794] | 0.071 |

| CVI n (%) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (0.1) | 1.017 [0.984–1.052] | <0.001 |

| Repeated PCI n (%) | 10 (2.0) | 76 (4.6) | 0.353 [0.047–2.634] | 0.432 |

| CABG n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 10 (0.7) | 0.994 [0.988–1.000] | 0.550 |

| MACCE n (%) | 40 (19.7) | 169 (10.3) | 1.711 [1.146–2.554] | 0.030 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | p Value | HR [95% CI] | p Value | |

| Age greater than 75 | 1.065 [1.065–2.300] | 0.023 | 1.493 [0.984–2.265] | 0.060 |

| Diabetes | 1.207 [0.857–1.700] | 0.281 | - - - | - - - |

| LVEF | 0.991 [0.977–1.005] | 0.220 | - - - | - - - |

| NSTEMI | 1.235 [0.800–1.904] | 0.341 | - - - | - - - |

| Multivessel disease | 1.451 [1.085–1.940] | 0.012 | 1.411 [1.052–1.893] | 0.022 |

| Chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL/min/m2) | 1.776 [0.850–3.710] | 0.126 | 1.521 [0.717–3.227] | 0.274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radunovic, A.; Ilic, I.; Matic, M.; Ostojic, M.; Kojic, D.; Golocevac, A.; Lazarevic, N.; Mandic, A.; Tomovic, M.; Otasevic, P. Clinical Outcomes After Immediate Coronary Angiography in Elderly Versus Younger Patients Suffering from Acute Coronary Syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090362

Radunovic A, Ilic I, Matic M, Ostojic M, Kojic D, Golocevac A, Lazarevic N, Mandic A, Tomovic M, Otasevic P. Clinical Outcomes After Immediate Coronary Angiography in Elderly Versus Younger Patients Suffering from Acute Coronary Syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(9):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090362

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadunovic, Anja, Ivan Ilic, Milica Matic, Miljana Ostojic, Dejan Kojic, Ana Golocevac, Nikola Lazarevic, Aleksandar Mandic, Milosav Tomovic, and Petar Otasevic. 2025. "Clinical Outcomes After Immediate Coronary Angiography in Elderly Versus Younger Patients Suffering from Acute Coronary Syndrome" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 9: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090362

APA StyleRadunovic, A., Ilic, I., Matic, M., Ostojic, M., Kojic, D., Golocevac, A., Lazarevic, N., Mandic, A., Tomovic, M., & Otasevic, P. (2025). Clinical Outcomes After Immediate Coronary Angiography in Elderly Versus Younger Patients Suffering from Acute Coronary Syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(9), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090362