Gastrointestinal Bleeding During Long-Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: External Validation of UTAH Bleeding Risk Score

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Risk Stratification

- (1)

- The HAS-BLED score evaluates the 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation and is calculated by assigning 1 point for each of the following factors: hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 160 mmHg), abnormal renal (creatinine ≥ 2.26 mg/dL, dialysis, or kidney transplant) or liver function (cirrhosis or significant hepatic impairment), stroke history, previous major bleeding or predisposition, labile INR (unstable or high INR if on warfarin), age ≥ 65 years, the use of drugs (antiplatelets and NSAIDs), or excessive alcohol consumption. The total score ranges from 0 to 9, classifying patients into low risk (0–2 points) and high risk (≥3 points), the latter indicating an increased likelihood of major bleeding events requiring closer monitoring [11].

- (2)

- The ARC-HBR (Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk) classification identifies patients at high risk of bleeding, particularly in those undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Patients are considered at a high bleeding risk if they meet at least one major criterion or two minor criteria. Major criteria include previous major bleeding within six months or recurrent bleeding, severe anemia (Hb < 11 g/dL) or transfusion dependency, thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/μL), chronic kidney disease (CrCl < 30 mL/min), active malignancy with a bleeding risk, and stroke with hemorrhagic transformation or severe disability. Minor criteria include age ≥ 75 years, moderate anemia (Hb 11–12.9 g/dL in men, 11–11.9 g/dL in women), chronic kidney disease (CrCl 30–59 mL/min), long-term oral anticoagulation therapy, a history of recurrent or spontaneous gastrointestinal bleeding, and moderate thrombocytopenia (100,000–149,000/μL) [10].

- (3)

- The UBRS (UTAH bleeding risk score) is calculated by attributing 1 or 2 points to specific variables: age > 54 years (1 point), coronary artery disease (1 point), chronic kidney disease (1 point), severe right ventricular (RV) dysfunction (1 point), mean pulmonary artery pressure < 18 mmHg (2 points), glucose > 107 mg/dL (1 point), and a history of previous bleeding (2 points). Based on the total score (ranging from 0 to 9), patients are stratified into low risk (0–1 point), intermediate risk (2–4 points), and high risk (5–9 points) [8].

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Definitions

2.4. Antithrombotic Therapy

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Procedural Characteristics

3.3. Bleeding Risk Stratification

- a.

- HASBLED score: A total of 73 (97.3%) of 75 patients had a HASBLED score ≤ 2. More precisely, 60 patients had a HASBLED value between zero and one, and 13 patients had a HASBLED score equal to two. The remaining two patients had a HASBLED score equal to three. None of the two patients with a score ≥ 3 developed a GIB, whereas 19 patients out of 73 with a score ≤ 2 (25%) had a GIB (p = 0.4). Therefore, the HASBLED score showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.52 (95% CI, 0.37–0.68) (Figure 1A).

- b.

- ARC-HBR score: Eight patients (10.6%) were ranked as low risk, and sixty-seven patients (89.4%) had a high-risk ARC-HBR profile. GIB occurred in 18 of 67 (27%) high-risk patients and in one of the 8 (12.5%) low-risk patients (p = 0.3). Furthermore, out of the 56 patients who did not have GIB, 49 (87.5%) were ranked as high risk. Therefore, the ARC-HBR showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.61 (95% CI, 0.47–0.75) (Figure 1B).

- c.

- UBRS: A total of 19 patients (25.3%) were ranked as low risk, 48 patients (64%) as intermediate risk, and 8 patients (10.7%) as high-risk, respectively. All eight patients classified as high risk had a GIB, whereas none of the nineteen patients classified as low risk had a GIB (p < 0.001). Out of the 48 patients classified as intermediate risk, 11 patients (23%) had a GIB, and 37 patients (77%) did not (p < 0.001). Finally, the performance of UBRS showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.76–0.95) (Figure 1C).

3.4. Clinical Follow-Up

3.5. Bleeding Complications and Outcome

4. Discussion

- The UBRS was effective at predicting the GIB risk of LVAD recipients, while the ARC-HBR and HASBLED scores were not.

- Patients on long-term VAD support showed a dual, dramatically high risk of developing MAEs and major bleeding complications.

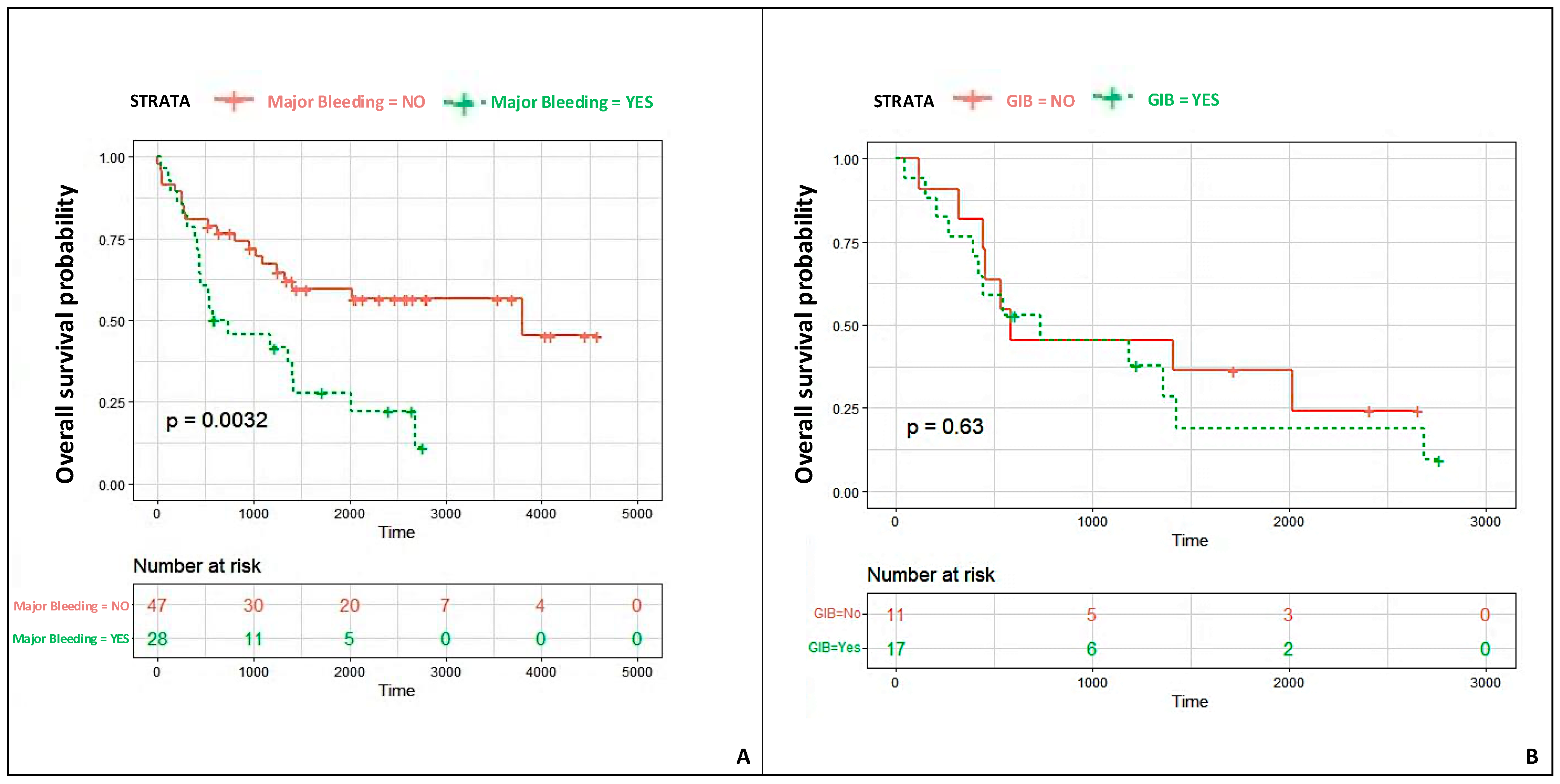

- Most major bleeding events were gastrointestinal and were associated with a significantly lower patient survival probability.

4.1. UBRS Validation and Applicability of Other Scores

4.2. Bleeding Events and Outcomes

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rose, E.A.; Gelijns, A.C.; Moskowitz, A.J.; Heitjan, D.F.; Stevenson, L.W.; Dembitsky, W.; Long, J.W.; Ascheim, D.D.; Tierney, A.R.; Levitan, R.G.; et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirklin, J.K.; Pagani, F.D.; Kormos, R.L.; Stevenson, L.W.; Blume, E.D.; Myers, S.L.; Miller, M.A.; Baldwin, J.T.; Young, J.B.; Naftel, D.C. Eighth annual INTERMACS report: Special focus on framing the impact of adverse events. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2017, 36, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, N.S.; Cool, J.; Karas, M.G.; Boehme, A.K.; Kamel, H. Stroke Risk and Mortality in Patients with Ventricular Assist Devices. Stroke 2016, 47, 2702–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maltais, S.; Kilic, A.; Nathan, S.; Keebler, M.; Emani, S.; Ransom, J.; Katz, J.N.; Sheridan, B.; Brieke, A.; Egnaczyk, G.; et al. PREVENtion of HeartMate II Pump Thrombosis Through Clinical Management: The PREVENT multi-center study. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2017, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, M.R.; Naka, Y.; Uriel, N.; Goldstein, D.J.; Cleveland JCJr Colombo, P.C.; Walsh, M.N.; Milano, C.A.; Patel, C.B.; Jorde, U.P.; Pagani, F.D.; et al. A Fully Magnetically Levitated Circulatory Pump for Advanced Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnesi, M.; Sammartino, A.M.; Chiarito, M.; Stolfo, D.; Baldetti, L.; Adamo, M.; Maggi, G.; Inciardi, R.M.; Tomasoni, D.; Loiacono, F.; et al. Clinical and prognostic implications of heart failure hospitalization in patients with advanced heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, V.; Amarelli, C.; Mattucci, I.; Bigazzi, M.C.; Cacciatore, F.; Maiello, C.; Golino, P. Predicting major events in ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure awaiting heart transplantation: A pilot study. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, M.Y.; Ruckel, S.; Kfoury, A.G.; McKellar, S.H.; Taleb, I.; Gilbert, E.M.; Nativi-Nicolau, J.; Stehlik, J.; Reid, B.B.; Koliopoulou, A.; et al. Novel Model to Predict Gastrointestinal Bleeding During Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. Circ. Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e005267, Erratum in Circ. Heart Fail. 2019, 12, e000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peivandi, A.; Welp, H.; Scherer, M.; Sindermann, J.R.; Wagner, N.M.; Dell’Aquila, A.M. An external validation study of the Utah Bleeding Risk Score. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezab572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, P.; Mehran, R.; Colleran, R.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Byrne, R.A.; Capodanno, D.; Cuisset, T.; Cutlip, D.; Eerdmans, P.; Eikelboom, J.; et al. Defining high bleeding risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A consensus document from the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2632–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, W.; He, W.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Hong, K. The HASBLED Score for Predicting Major Bleeding Risk in Anticoagulated Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2015, 38, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehran, R.; Rao, S.V.; Bhatt, D.L.; Gibson, C.M.; Caixeta, A.; Eikelboom, J.; Kaul, S.; Wiviott, S.D.; Menon, V.; Nikolsky, E.; et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: A consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation 2011, 123, 2736–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.J.; John, R.; Salerno, C.; Silvestry, S.; Moazami, N.; Horstmanshof, D.; Adamson, R.; Boyle, A.; Zucker, M.; Rogers, J.; et al. Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of suspected pump thrombus. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2013, 32, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, A.J.; Jorde, U.P.; Sun, B.; Park, S.J.; Milano, C.A.; Frazier, O.H.; Sundareswaran, K.S.; Farrar, D.J.; Russell, S.D.; HeartMate II Clinical Investigators. Pre-operative risk factors of bleeding and stroke during left ventricular assist device support: An analysis of more than 900 HeartMate II outpatients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, P.S.; Kumar, G.; Guddati, A.K.; Bhama, J.K.; Cadaret, L.M. Risk factors and outcomes of gastrointestinal bleeding in left ventricular assist device recipients. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 117, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, A.C.; Chen, C.W.; Chung, J.J.; Han, J.; Bermudez, C.A.; Wald, J.; Atluri, P. Is there a difference in bleeding after left ventricular assist device implant: Centrifugal versus axial? J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jabbar, H.R.; Abbas, A.; Ahmed, M.; Klodell, C.T.; Chang, M.; Dai, Y.; Draganov, P.V. The incidence, predictors and outcomes of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 3697–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, J.; Dogan, G.; Mariani, S.; Deniz, E.; Merzah, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Haverich, A.; Schmitto, J.D. Effect of artificial pulse and pulsatility on gastrointestinal bleeding rates after left ventricular assist device implantation. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 68 (Suppl. S01), S1–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moady, G.; Ben Avraham, B.; Aviv, S.; Ben Zadok, O.I.; Atar, S.; Abu Akel, M.; Ben Gal, T. The safety of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in patients with left ventricular assist device—A single center experience. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, E.J.; Shah, P.; Kiernan, M.S.; Cornwell WK 3rd Copeland, H.; Takeda, K.; Fernandez, F.G.; Badhwar, V.; Habib, R.H.; Jacobs, J.P.; Koehl, D.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2020 Annual Report. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 111, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.G.; Pagani, F.D.; Tatooles, A.J.; Bhat, G.; Slaughter, M.S.; Birks, E.J.; Boyce, S.W.; Najjar, S.S.; Jeevanandam, V.; Anderson, A.S.; et al. Intrapericardial Left Ventricular Assist Device for Advanced Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stulak, J.M.; Lee, D.; Haft, J.W.; Romano, M.A.; Cowger, J.A.; Park, S.J.; Aaronson, K.D.; Pagani, F.D. Gastrointestinal bleeding and subsequent risk of thromboembolic events during support with a left ventricular assist device. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2014, 33, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erriquez, A.; Campo, G.; Guiducci, V.; Escaned, J.; Moreno, R.; Casella, G.; Menozzi, M.; Cerrato, E.; Sacchetta, G.; Menozzi, A.; et al. Complete vs Culprit-Only Revascularization in Older Patients with Myocardial Infarction and High Bleeding Risk: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jennings, D.L.; Rimsans, J.; Connors, J.M. Prothrombin Complex Concentrate for Warfarin Reversal in Patients with Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices: A Narrative Review. ASAIO J. 2020, 66, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadalà, G.; Galassi, A.R.; Werner, G.S.; Sianos, G.; Boudou, N.; Garbo, R.; Maniscalco, L.; Bufe, A.; Avran, A.; Gasparini, G.L.; et al. Contemporary outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention in Europe: The ERCTO registry. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e185–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Overall (n = 75) | No GIB (n = 54) | GIB (n = 21) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.8 ± 8.87 | 56.8 ± 9.7 | 60.2 ± 5.5 | 0.344 |

| Female | 7 (9.3) | 7 (12.9) | 0 | N.S. |

| Hypertension | 45 (60.0) | 34 (63.0) | 11 (52.0) | 0.4 |

| Hypercolesterolemia | 36 (48.0) | 25 (46.0) | 11 (52.0) | 0.6 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 32 (43.0) | 20 (37.0) | 12 (57.0) | 0.11 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) | 42 (56.0) | 28 (52.0) | 14 (67.0) | 0.2 |

| Coronary Artery disease (CAD) | 36 (48.0) | 25 (46.0) | 11 (52.0) | 0.6 |

| NYHA class | ||||

| III | 44 (59.0) | 34 (63.0) | 10 (48.0) | 0.2 |

| IV | 31 (41.0) | 20 (37.0) | 11 (52.0) | 0.2 |

| INTERMACS patient profile | ||||

| 1 | 8 (10.6) | 6 (11.1) | 2 (9.5) | 0.815 |

| 2 | 32 (42.6) | 22 (40.7) | 10 (47.6) | |

| 3 | 20 (26.6) | 16 (29.6) | 4 (19.0) | |

| 4 | 15 (20.0) | 10 (18.5) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Etiology of heart failure | ||||

| Ischemic | 36 (48.0) | 25 (46.3) | 11 (52.4) | 0.828 |

| Dilatative Cardiomyopathy | 29 (38.6) | 21 (38.9) | 8 (38.1) | 1 |

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy | 5 (6.6) | 4 (7.4) | 1 (4.8) | 1 |

| Chemotherapy Induced Cardiomyopathy | 3 (4.0) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (4.8) | 1 |

| Myocarditis | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | N.S. |

| Valvular Cardiopathy | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | N.S. |

| Indication | ||||

| Bridge to Transplant (BTT) | 35 (46.6) | 26 (48.1) | 9 (42.8) | 0.942 |

| Bridge to Candidacy (BTC) | 26 (34.8) | 18 (33.3) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Destination Therapy (DT) | 14 (18.6) | 10 (18.5) | 4 (19.1) | |

| Overall (n = 75) | No GIB (n = 54) | GIB (n = 21) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device Type | ||||

| HeartWare (HVAD) | 70 (93.0) | 51 (94.4) | 19 (90.5) | 0.615 |

| HeartMate III (HM III) | 5 (7.0) | 3 (5.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Inotropes/vasopressor | ||||

| Epinephrine | 72 (96.0) | 53 (95.0) | 19 (100.0) | 0.991 |

| Norepinephrine | 60 (80.0) | 46 (82.0) | 14 (74.0) | 0.429 |

| Dobutamine | 16 (21.3) | 13 (23.0) | 3 (16.0) | 0.497 |

| Milrinone | 32 (43.0) | 23 (41.0) | 9 (47.0) | 0.631 |

| Enoximone | 2 (2.6) | 2 (3.6) | 0 | N.S. |

| Vasopressin | 6 (8.0) | 3 (5.0) | 3 (16.0) | 0.166 |

| Mechanical Circulatory Support | ||||

| IAPB | 36 (48.0) | 25 (44.6) | 11 (57.9) | 0.259 |

| ECMO | 2 (2.6) | 2 (3.6) | 0 | N.S. |

| Transfusion of blood products | 42 (56.0) | 28 (52.0) | 14 (67.0) | 0.2 |

| RBCs (n° of units) | 3.1 ± 3.5 | 2.3 ± 3.4 | 2,4 ± 2.7 | 0.866 |

| PLTs (n° of units) | 2 ± 4.5 | 1.4 ± 3 | 3.6 ± 7 | 0.117 |

| FFP (n° of units) | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.838 |

| Blood samples | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.2 ± 2 | 11.4 ± 2 | 10.9 ± 2 | 0.350 |

| Platelets (×103/uL) | 229 ± 87 | 227 ± 84 | 233 ± 95 | 0.802 |

| eGFR, CKD-EPI (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 67.8 ± 23 | 66 ± 21 | 72.6 ± 28.5 | 0.301 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 6835 ± 9430 | 7527 ± 10,475 | 4798 ± 4700 | 0.317 |

| Renal Replacement Therapy | 26 (35.0) | 18 (32.1) | 8 (38.0) | 0.697 |

| Overall (n = 75) | No GIB (n = 54) | GIB (n = 21) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up duration (days) | 1598 ± 1107 | 1955 ± 1119 | 951 ± 1468 | 0.062 |

| Duration of VAD support (days) | 905.9 ± 724 | 881 ± 688 | 968 ± 825 | <0.001 |

| Transplant | 22 (29.3) | 18 (33.3) | 4 (19.0) | 0.269 |

| Total number of MAEs | 100 | 68 | 29 | 0.480 |

| Patients with MAE | 58 (77.3) | 42 (77.7) | 16 (76.2) | 0.989 |

| Patients with multiple MAEs | 27 (36) | 17 (31.5) | 10 (47.6) | 0.191 |

| MAEs/patients | 1.72 | 1.62 | 1.81 | 0.480 |

| Death | 41 (54.6) | 28 (51.8) | 13 (61.9) | 0.598 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 3 (4) | 3 (5) | - | N.S. |

| Ischemic stroke | 16 (21.3) | 11 (20.3) | 5 (23.8) | 0.759 |

| Hospitalization for right ventricular failure | 16 (21.3) | 10 (18.5) | 6 (28.5) | 0.340 |

| Hospitalization for VAD failure | 16 (21.3) | 12 (22) | 4 (19) | 0.763 |

| VAD thrombosis | 8 (10.6) | 6 (11.1) | 2 (9.5) | 1 |

| Total number of major bleeding events | 39 | 13 | 26 | |

| Patients with major bleeding | 28 (37.3) | 11 (20.3) | 17 (81) | <0.001 |

| Patients with multiple major bleeding events | 12 (16) | 3 (5.5) | 9 (43) | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding events/patient | 1.43 | 1.18 | 1.53 | <0.001 |

| GIB | 17 (43.5) | 0 | 17 (65) | <0.001 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 13 (33.3) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (23) | 0.054 |

| Hemothorax | 3 (7.7) | 2 (15.3) | 1 (3.8) | 0.202 |

| Nasopharyngeal hemorrhage | 5 (12.8) | 3 (23) | 2 (7.7) | 0.175 |

| Colonstomy bleeding | 1 (2.6) | 1 (7.7) | - | 0.151 |

| Other complications | ||||

| VAD driveline infection | 13 (17.3) | 8 (14.8) | 5 (23.8) | 0.497 |

| Sepsis | 18 (24) | 14 (25.9) | 4 (19) | 0.558 |

| Wound dehiscence | 17 (22.6) | 15 (27.7) | 2 (9.5) | 0.124 |

| Pneumonia | 6 (8) | 4 (7.4) | 2 (9.5) | 1 |

| Pleural effusion | 5 (6.7) | 4 (7.4) | 1 (4.7) | 1 |

| Acute renal failure | 5 (6.7) | 4 (7.4) | 1 (4.7) | 1 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 2 (2.6) | 2 (3.7) | - | N.S. |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.8) | - | N.S. |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | 1 (1.3) | - | 1 (4.7) | N.S. |

| Cognitive impairment | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.7) | 0.501 |

| Pneumothorax | 2 (2.6) | 2 (3.7) | - | N.S. |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.8) | - | N.S. |

| Endocarditis | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.8) | - | N.S. |

| SARS-CoV 2 infection | 3 (4) | 3 (5.6) | - | N.S. |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 20 (26.6) | 14 (25.9) | 6 (28.5) | 0.563 |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.8) | - | N.S. |

| Vascular access bleeding | 1 (14.2) | 1 (33.3) | - | N.S. |

| Nasopharyngeal hemorrhages | 1 (14.2) | 1 (33.3) | - | N.S. |

| Hemothorax | 1 (14.2) | 1 (33.3) | - | N.S. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vadalà, G.; Madaudo, C.; Fontana, A.; Sucato, V.; Bicelli, G.; Maniscalco, L.; Parlati, A.L.M.; Panarello, G.; Sciacca, S.; Pilato, M.; et al. Gastrointestinal Bleeding During Long-Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: External Validation of UTAH Bleeding Risk Score. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12030105

Vadalà G, Madaudo C, Fontana A, Sucato V, Bicelli G, Maniscalco L, Parlati ALM, Panarello G, Sciacca S, Pilato M, et al. Gastrointestinal Bleeding During Long-Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: External Validation of UTAH Bleeding Risk Score. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(3):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12030105

Chicago/Turabian StyleVadalà, Giuseppe, Cristina Madaudo, Alessandra Fontana, Vincenzo Sucato, Gioele Bicelli, Laura Maniscalco, Antonio Luca Maria Parlati, Giovanna Panarello, Sergio Sciacca, Michele Pilato, and et al. 2025. "Gastrointestinal Bleeding During Long-Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: External Validation of UTAH Bleeding Risk Score" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 3: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12030105

APA StyleVadalà, G., Madaudo, C., Fontana, A., Sucato, V., Bicelli, G., Maniscalco, L., Parlati, A. L. M., Panarello, G., Sciacca, S., Pilato, M., Cipriani, M., & Galassi, A. R. (2025). Gastrointestinal Bleeding During Long-Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: External Validation of UTAH Bleeding Risk Score. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(3), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12030105