Contaminant Metals and Cardiovascular Health

Abstract

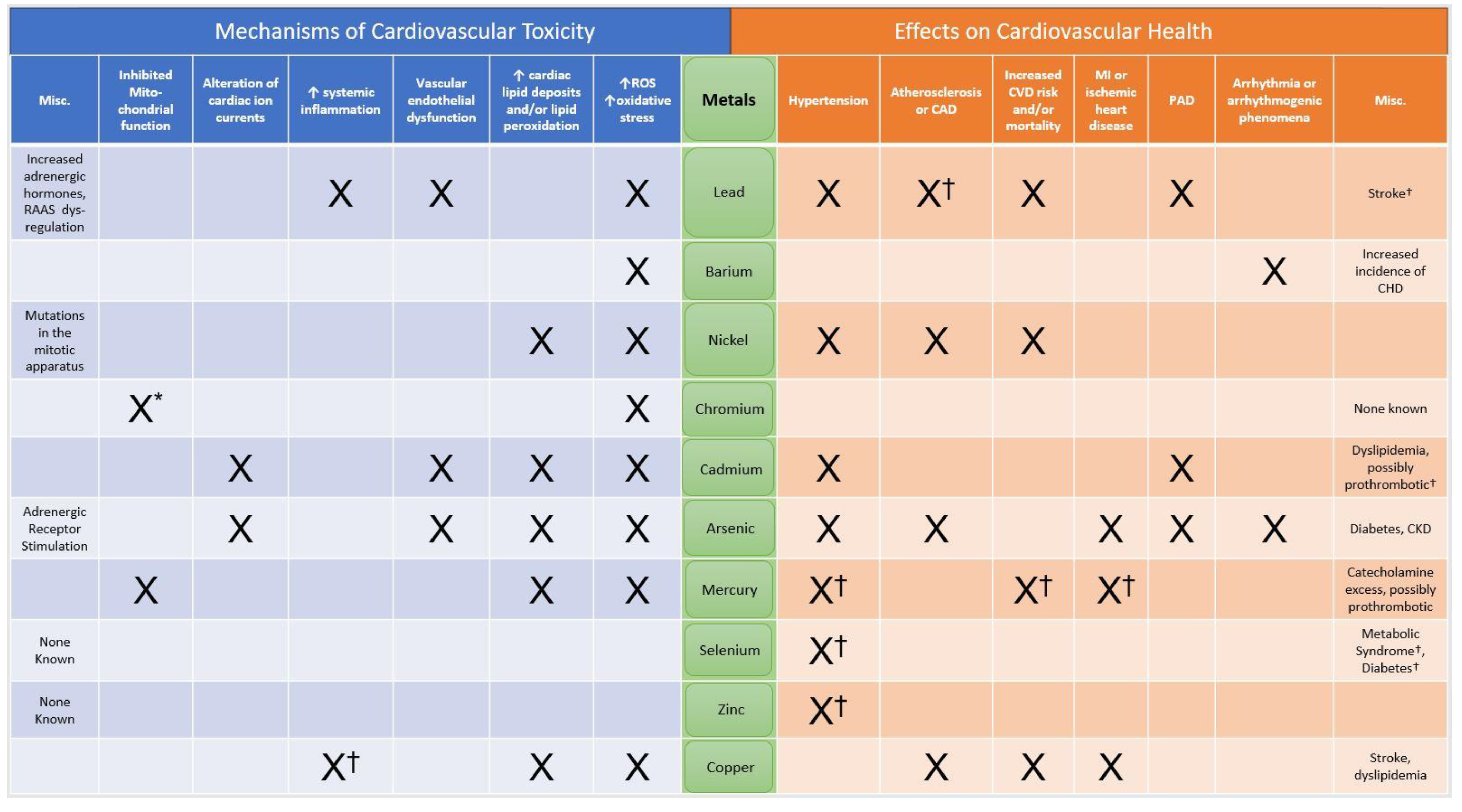

1. Introduction

2. Lead

3. Barium

4. Nickel

5. Chromium

6. Cadmium

7. Arsenic

8. Mercury

9. Selenium

10. Zinc

11. Copper

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ap-1 | activator protein 1 |

| As | Arsenic |

| AV | atrioventricular |

| Ba | Barium |

| BFD | Blackfoot disease |

| BKMR | Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| CHD | congenital heart disease |

| CI | confidence interval |

| Co | Cobalt |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Cu | Copper |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| COMT | catecholamine-O-methyltransferase |

| CYP450 | cytochrome p450 |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| DMT | divalent metal transporter |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| ET-1 | endothelin 1 |

| Fe | Iron |

| GTF | glucose tolerance factor |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| HF | heart failure |

| Hg | Mercury |

| HOMA-IR | homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance |

| HTN | hypertension |

| ICM | ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| IDCM | idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy |

| IHD | ischemic heart disease |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LF | low frequency |

| LOX-1 | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 |

| MACE | major adverse cardiovascular event |

| MAPK38 | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MeHg | methylmercury |

| mRNA | messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NF-kB | nuclear factor-kB |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| Ni | Nickel |

| NK-1 | neurokinin 1 |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NOS | nitric oxide synthase |

| Nox2 | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| PAD | peripheral artery disease |

| Pb | Lead |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| PM | particular matter |

| RAAS | renin–angiotensinogen–aldosterone |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SDNN | standard deviation of RR intervals |

| Se | Selenium |

| SERCA2 | sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase 2 |

| SES | socioeconomic status |

| SMD | standard mean difference |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TPN | total parenteral nutrition |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion protein 1 |

| VLDL | very-low-density lipoprotein |

| Zn | zinc |

References

- Krittanawong, C.; Qadeer, Y.K.; Hayes, R.B.; Wang, Z.; Virani, S.; Thurston, G.D.; Lavie, C.J. PM2.5 and Cardiovascular Health Risks. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haar, G.T. Lead in the Environment—Origins, Pathways and Sinks. Environ. Qual. Safety. Suppl. 1975, 2, 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng-Gyasi, E. Sources of Lead Exposure in Various Countries. Rev. Environ. Health 2019, 34, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Harrison, D.G. Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases: The Role of Oxidant Stress. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, B. Mechanisms of Disease: Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Hypertension. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2006, 2, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonick, H.C.; Ding, Y.; Bondy, S.C.; Ni, Z.; Vaziri, N.D. Lead-Induced Hypertension: Interplay of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species. Hypertension 1997, 30, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, C.M.; Newton, A.C. The Life and Death of Protein Kinase C. Curr. Drug Targets 2008, 9, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.W.; Chai, S.; Webb, R.C. Lead Acetate-Induced Contraction in Rabbit Mesenteric Artery: Interaction with Calcium and Protein Kinase C. Toxicology 1995, 99, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Hong, J.T. Roles of NF-κB in Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases and Their Therapeutic Approaches. Cells 2016, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Sindhu, R.K.; Quiroz, Y.; Vaziri, N.D. Chronic Exposure to Low Doses of Lead Results in Renal Infiltration of Immune Cells, NF-kappaB Activation, and Overexpression of Tubulointerstitial Angiotensin II. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005, 7, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, Y.; Quiroz, Y.; Ferrebuz, A.; Vaziri, N.D.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, B. Mycophenolate Mofetil Administration Reduces Renal Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Arterial Pressure in Rats with Lead-Induced Hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2007, 293, F616–F623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.R.; Chen, S.S.; Chen, T.J.; Ho, C.H.; Chiang, H.C.; Yu, H.S. Lymphocyte Beta2-Adrenergic Receptors and Plasma Catecholamine Levels in Lead-Exposed Workers. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1996, 139, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil-Manesh, F.; Gonick, H.C.; Weiler, E.W.; Prins, B.; Weber, M.A.; Purdy, R.E. Lead-Induced Hypertension: Possible Role of Endothelial Factors. Am. J. Hypertens 1993, 6, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffrin, E.L. Role of Endothelin-1 in Hypertension and Vascular Disease. Am. J. Hypertens 2001, 14 Pt 2, 83S–89S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander, A.J. Chronic Effects of Lead on the Renin-Angiotensin System. Environ. Health Perspect. 1988, 78, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustberg, M.; Silbergeld, E. Blood Lead Levels and Mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 2443–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, S.E.; Mirel, L.B.; Graubard, B.I.; Brody, D.J.; Flegal, K.M. Blood Lead Levels and Death from All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: Results from the NHANES III Mortality Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntner, P.; Menke, A.; DeSalvo, K.B.; Rabito, F.A.; Batuman, V. Continued Decline in Blood Lead Levels among Adults in the United States: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 2155–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Acien, A.; Selvin, E.; Sharrett, A.R.; Calderon-Aranda, E.; Silbergeld, E.; Guallar, E. Lead, Cadmium, Smoking, and Increased Risk of Peripheral Arterial Disease. Circulation 2004, 109, 3196–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, S.J.; Shaper, A.G.; Ashby, D.; Delves, H.T.; Clayton, B.E. The Relationship between Blood Lead, Blood Pressure, Stroke, and Heart Attacks in Middle-Aged British Men. Environ. Health Perspect. 1988, 78, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromhout, D. Blood Lead and Coronary Heart Disease Risk among Elderly Men in Zutphen, The Netherlands. Environ. Health Perspect. 1988, 78, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, L.; Kristensen, T.S. Blood Lead as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 136, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Schwartz, J.; Vokonas, P.S.; Weiss, S.T.; Aro, A.; Hu, H. Electrocardiographic Conduction Disturbances in Association with Low-Level Lead Exposure (the Normative Aging Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 82, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas-Acien, A.; Guallar, E.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Rothenberg, S.J. Lead Exposure and Cardiovascular Disease—A Systematic Review. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, B.T.P.; Almeida, M.G.D.; Rezende, C.E.D. Barium and Its Importance as an Indicator of (Paleo)Productivity. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2016, 88, 2093–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, M.; Medici, S.; Dadar, M.; Zoroddu, M.A.; Pelucelli, A.; Chasapis, C.T.; Bjørklund, G. Environmental Barium: Potential Exposure and Health-Hazards. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 2605–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoelan, B.S.; Stevering, C.H.; van der Boog, A.T.J.; van der Heyden, M.a.G. Barium Toxicity and the Role of the Potassium Inward Rectifier Current. Clin. Toxicol. 2014, 52, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wones, R.G.; Stadler, B.L.; Frohman, L.A. Lack of Effect of Drinking Water Barium on Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Environ. Health Perspect. 1990, 85, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, H.M.; Kopp, S.J.; Perry, E.F.; Erlanger, M.W. Hypertension and Associated Cardiovascular Abnormalities Induced by Chronic Barium Feeding. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 1989, 28, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenniman, G.R.; Namekata, T.; Kojola, W.H.; Carnow, B.W.; Levy, P.S. Cardiovascular Disease Death Rates in Communities with Elevated Levels of Barium in Drinking Water. Environ. Res. 1979, 20, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barium|Public Health Statement|ATSDR. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=325&toxid=57 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Barceloux, D.G. Nickel. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genchi, G.; Carocci, A.; Lauria, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Catalano, A. Nickel: Human Health and Environmental Toxicology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, E.L.B.; Diniz, Y.S.; Machado, T.; ProenÇa, V.; TibiriÇÁ, T.; Faine, L.; Ribas, B.O.; Almeida, J.A. Toxic Mechanism of Nickel Exposure on Cardiac Tissue. Toxic Subst. Mech. 2000, 19, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.-L.; Guo, Y.-X.; Li, N.; Lin, Y.; Yu, P.; Liu, Z.; et al. Metal Nickel Exposure Increase the Risk of Congenital Heart Defects Occurrence in Offspring: A Case-Control Study in China. Medicine 2019, 98, e15352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Buchner, V.; Tchounwou, P.B. Exploring the Molecular Mechanisms of Nickel-Induced Genotoxicity and Carcinogenicity: A Literature Review. Rev. Environ. Health 2011, 26, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, J.E.; Costa, M. Epigenetics and the Environment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 983, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Verma, U.N.; Costa, M.; Huang, C. Soluble and Insoluble Nickel Compounds Exert a Differential Inhibitory Effect on Cell Growth through IKKalpha-Dependent Cyclin D1 down-Regulation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2009, 218, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheek, J.; Fox, S.S.; Lehmler, H.-J.; Titcomb, T.J. Environmental Nickel Exposure and Cardiovascular Disease in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Expo. Health 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, P.M.; Olsén, L.; Lind, L. Circulating Levels of Metals Are Related to Carotid Atherosclerosis in Elderly. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 416, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Liu, S.; Xia, X.; Qian, J.; Jing, H.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Identification of the Hormetic Dose-Response and Regulatory Network of Multiple Metals Co-Exposure-Related Hypertension via Integration of Metallomics and Adverse Outcome Pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 153039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Nickel. US EPA. Available online: https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/wqc/ambient-water-quality-criteria-nickel (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Zayed, A.M.; Terry, N. Chromium in the Environment: Factors Affecting Biological Remediation. Plant Soil 2003, 249, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillrud, S.N.; Epstein, D.; Ross, J.M.; Sax, S.N.; Pederson, D.; Spengler, J.D.; Kinney, P.L. Elevated Airborne Exposures of Teenagers to Manganese, Chromium, and Iron from Steel Dust and New York City’s Subway System. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chillrud, S.N.; Grass, D.; Ross, J.M.; Coulibaly, D.; Slavkovich, V.; Epstein, D.; Sax, S.N.; Pederson, D.; Johnson, D.; Spengler, J.D.; et al. Steel Dust in the New York City Subway System as a Source of Manganese, Chromium, and Iron Exposures for Transit Workers. J. Urban Health 2005, 82, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, M.; Standl, E.; Schnell, O. Chromium in Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease. Horm. Metab. Res. 2007, 39, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonoff, M. Chromium Deficiency and Cardiovascular Risk. Cardiovasc. Res. 1984, 18, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Xun, P.; Morris, S.; Jacobs, D.R.; Liu, K.; He, K. Chromium Exposure and Incidence of Metabolic Syndrome among American Young Adults over a 23-Year Follow-up: The CARDIA Trace Element Study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kan, M.; Ratnasekera, P.; Deol, L.K.; Thakkar, V.; Davison, K.M. Blood Chromium Levels and Their Association with Cardiovascular Diseases, Diabetes, and Depression: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2015–2016. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Muñoz-Bravo, C.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Mariscal, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Fito, M.; et al. Chromium Exposure and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in High Cardiovascular Risk Subjects—Nested Case-Control Study in the Prevention With Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED) Study. Circ. J. 2017, 81, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, H.A.; Leighton, R.F.; Lanese, R.R.; Freedland, N.A. Serum Chromium and Angiographically Determined Coronary Artery Disease. Clin. Chem. 1978, 24, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guallar, E.; Jiménez, F.J.; van ’t Veer, P.; Bode, P.; Riemersma, R.A.; Gómez-Aracena, J.; Kark, J.D.; Arab, L.; Kok, F.J.; Martín-Moreno, J.M.; et al. Low Toenail Chromium Concentration and Increased Risk of Nonfatal Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 162, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeback, J.R.; Hla, K.M.; Chambless, L.E.; Fletcher, R.H. Effects of Chromium Supplementation on Serum High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Men Taking Beta-Blockers. A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 115, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price Evans, D.A.; Tariq, M.; Dafterdar, R.; Al Hussaini, H.; Sobki, S.H. Chromium Chloride Administration Causes a Substantial Reduction of Coronary Lipid Deposits, Aortic Lipid Deposits, and Serum Cholesterol Concentration in Rabbits. Biol Trace Elem. Res. 2009, 130, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, H.A.; balassa, J.J. Influence of chromium, cadmium, and lead on rat aortic lipids and circulating cholesterol. Am. J. Physiol. 1965, 209, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnama-Moghadam, S.; Hillis, L.D.; Lange, R.A. Chapter 3—Environmental Toxins and the Heart. In The Heart and Toxins; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhitkovich, A. Chromium in Drinking Water: Sources, Metabolism, and Cancer Risks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Bharagava, R.N. Toxic and Genotoxic Effects of Hexavalent Chromium in Environment and Its Bioremediation Strategies. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 2016, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, E.; Derazon, H.; Eisenberg, Y.; Natalia, B. Suicide by Ingestion of a CCA Wood Preservative. J. Emerg. Med. 2000, 19, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, J.; Gao, H.; Yang, X.; Fu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, D. Hexavalent Chromium Causes Apoptosis and Autophagy by Inducing Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Broiler Cardiomyocytes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 2866–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Baker, J.R.; Urbenjapol, S.; Haswell-Elkins, M.; Reilly, P.E.B.; Williams, D.J.; Moore, M.R. A Global Perspective on Cadmium Pollution and Toxicity in Non-Occupationally Exposed Population. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 137, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezynska, M.; Brzóska, M.M. Environmental Exposure to Cadmium-a Risk for Health of the General Population in Industrialized Countries and Preventive Strategies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 3211–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verougstraete, V.; Lison, D.; Hotz, P. Cadmium, Lung and Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review of Recent Epidemiological Data. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2003, 6, 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, A.; Muntner, P.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Platz, E.A.; Guallar, E. Cadmium Levels in Urine and Mortality among U.S. Adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, B.; Bernhard, D. Cadmium and Cardiovascular Diseases: Cell Biology, Pathophysiology, and Epidemiological Relevance. Biometals 2010, 23, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouhamed, M.; Wolff, N.A.; Lee, W.-K.; Smith, C.P.; Thévenod, F. Knockdown of Endosomal/Lysosomal Divalent Metal Transporter 1 by RNA Interference Prevents Cadmium-Metallothionein-1 Cytotoxicity in Renal Proximal Tubule Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2007, 293, F705–F712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, N.A.; Lee, W.-K.; Abouhamed, M.; Thévenod, F. Role of ARF6 in Internalization of Metal-Binding Proteins, Metallothionein and Transferrin, and Cadmium-Metallothionein Toxicity in Kidney Proximal Tubule Cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 230, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffensen, I.L.; Mesna, O.J.; Andruchow, E.; Namork, E.; Hylland, K.; Andersen, R.A. Cytotoxicity and Accumulation of Hg, Ag, Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn in Human Peripheral T and B Lymphocytes and Monocytes in Vitro. Gen. Pharmacol. 1994, 25, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prozialeck, W.C.; Edwards, J.R.; Woods, J.M. The Vascular Endothelium as a Target of Cadmium Toxicity. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hayyeh, S.; Sian, M.; Jones, K.G.; Manuel, A.; Powell, J.T. Cadmium Accumulation in Aortas of Smokers. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, T.; Yamamoto, C.; Tsubaki, S.; Ohkawara, S.; Sakamoto, M.; Sato, M.; Kozuka, H. Metallothionein Induction by Cadmium, Cytokines, Thrombin and Endothelin-1 in Cultured Vascular Endothelial Cells. Life Sci. 1993, 53, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, D.; Rossmann, A.; Henderson, B.; Kind, M.; Seubert, A.; Wick, G. Increased Serum Cadmium and Strontium Levels in Young Smokers: Effects on Arterial Endothelial Cell Gene Transcription. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.M.; Leone, M.; Klosowska, K.; Lamar, P.C.; Shaknovsky, T.J.; Prozialeck, W.C. Direct Antiangiogenic Actions of Cadmium on Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2008, 22, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, B.; Knoflach, M.; Seubert, A.; Ritsch, A.; Pfaller, K.; Henderson, B.; Shen, Y.H.; Zeller, I.; Willeit, J.; Laufer, G.; et al. Cadmium Is a Novel and Independent Risk Factor for Early Atherosclerosis Mechanisms and in Vivo Relevance. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.-S.; Jeong, E.-M.; Park, E.K.; Kim, Y.-M.; Sohn, S.; Lee, S.H.; Baik, E.J.; Moon, C.-H. Cadmium Induces Apoptotic Cell Death through P38 MAPK in Brain Microvessel Endothelial Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 578, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, H.; Nishijo, M. Environmental Cadmium Exposure, Hypertension and Cardiovascular Risk. J. Cardiovasc. Risk 1996, 3, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eum, K.-D.; Lee, M.-S.; Paek, D. Cadmium in Blood and Hypertension. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 407, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellez-Plaza, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Crainiceanu, C.M.; Guallar, E. Cadmium Exposure and Hypertension in the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-Y.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lim, K.-M.; Chung, S.-M.; Bae, O.-N.; Kim, H.; Lee, C.-R.; Park, J.-D.; Chung, J.-H. Inorganic Arsenite Potentiates Vasoconstriction through Calcium Sensitization in Vascular Smooth Muscle. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Ge, J.; Zhang, C.; Lv, M.-W.; Zhang, Q.; Talukder, M.; Li, J.-L. `Cadmium Induced Cardiac Inflammation in Chicken (Gallus gallus) via Modulating Cytochrome P450 Systems and Nrf2 Mediated Antioxidant Defense. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 125858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.L.; Kabir, R.; Ebenebe, O.V.; Taube, N.; Garbus, H.; Sinha, P.; Wang, N.; Mishra, S.; Lin, B.L.; Muller, G.K.; et al. Cadmium Exposure Induces a Sex-Dependent Decline in Left Ventricular Cardiac Function. Life Sci. 2023, 324, 121712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalska, J.; Brzóska, M.M.; Roszczenko, A.; Moniuszko-Jakoniuk, J. Enhanced Zinc Consumption Prevents Cadmium-Induced Alterations in Lipid Metabolism in Male Rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 177, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluranti, O.I.; Agboola, E.A.; Fubara, N.E.; Ajayi, M.O.; Michael, O.S. Cadmium Exposure Induces Cardiac Glucometabolic Dysregulation and Lipid Accumulation Independent of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Activity. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Zhang, S.-L.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Tian, Y.; Sun, Q. Cadmium Toxicity Induces ER Stress and Apoptosis via Impairing Energy Homoeostasis in Cardiomyocytes. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35, e00214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, H. Cadmium Induced Cardiac Toxicology in Developing Japanese Quail (Coturnix japonica): Histopathological Damages, Oxidative Stress and Myocardial Muscle Fiber Formation Disorder. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 250, 109168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, I.M.; Buyukakilli, B.; Balli, E.; Cimen, B.; Gunes, S.; Erdogan, S. Determination of Acute and Chronic Effects of Cadmium on the Cardiovascular System of Rats. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2009, 19, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverinen, J.; Badr, A.; Vornanen, M. Cardiac Toxicity of Cadmium Involves Complex Interactions Among Multiple Ion Currents in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Ventricular Myocytes. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 2874–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.B.; Jiang, B.; Pappano, A.J. Comparison of L-Type Calcium Channel Blockade by Nifedipine and/or Cadmium in Guinea Pig Ventricular Myocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 294, 562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Follmer, C.H.; Lodge, N.J.; Cullinan, C.A.; Colatsky, T.J. Modulation of the Delayed Rectifier, IK, by Cadmium in Cat Ventricular Myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1992, 262 Pt 1, C75–C83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, B.A. Monitoring of Human Populations for Early Markers of Cadmium Toxicity: A Review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 238, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M. Arsenic Poisoning through Ages: Victims of Venom. In Arsenic in Groundwater; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garbinski, L.D.; Rosen, B.P.; Chen, J. Pathways of Arsenic Uptake and Efflux. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, T.-C.; Yeh, S.C.; Tsai, E.-M.; Tsai, F.-Y.; Chao, H.-R.; Chang, L.W. Arsenite Enhances Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha-Induced Expression of Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 209, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinsworth, D.C. Arsenic, Reactive Oxygen, and Endothelial Dysfunction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2015, 353, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuntharatanapong, N.; Chen, K.; Sinhaseni, P.; Keaney, J.F. EGF Receptor-Dependent JNK Activation Is Involved in Arsenite-Induced p21Cip1/Waf1 Upregulation and Endothelial Apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H99–H107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Tsai, M.-H.; Wang, H.-J.; Yu, H.-S.; Chang, L.W. Involvement of Substance P and Neurogenic Inflammation in Arsenic-Induced Early Vascular Dysfunction. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 95, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakumar, P.; Kaur, J. Arsenic Exposure and Cardiovascular Disorders: An Overview. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2009, 9, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.; Hsieh, F.-I.; Lien, L.-M.; Chou, Y.-L.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-J. Risk of Carotid Atherosclerosis Associated with Genetic Polymorphisms of Apolipoprotein E and Inflammatory Genes among Arsenic Exposed Residents in Taiwan. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 227, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Wu, M.-M.; Hong, C.-T.; Lien, L.-M.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Tseng, H.-P.; Chang, S.-F.; Su, C.-L.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-J. Effects of Arsenic Exposure and Genetic Polymorphisms of P53, Glutathione S-Transferase M1, T1, and P1 on the Risk of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Taiwan. Atherosclerosis 2007, 192, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, J.; Yamauchi, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Sun, G.; Yoshida, T.; Aikawa, H.; Hopenhayn-Rich, C.; Shimojo, N. Evidence for Induction of Oxidative Stress Caused by Chronic Exposure of Chinese Residents to Arsenic Contained in Drinking Water. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, E.; Ota, A.; Karnan, S.; Damdindorj, L.; Takahashi, M.; Konishi, Y.; Konishi, H.; Hosokawa, Y. Arsenic Augments the Uptake of Oxidized LDL by Upregulating the Expression of Lectin-like Oxidized LDL Receptor in Mouse Aortic Endothelial Cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 273, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Ramachandra, C.J. 20—Arsenic and Cardiovascular System. In Handbook of Arsenic Toxicology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 517–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmignani, M.; Boscolo, P.; Castellino, N. Metabolic Fate and Cardiovascular Effects of Arsenic in Rats and Rabbits Chronically Exposed to Trivalent and Pentavalent Arsenic. Arch. Toxicol. Suppl. 1985, 8, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soucy, N.V.; Mayka, D.; Klei, L.R.; Nemec, A.A.; Bauer, J.A.; Barchowsky, A. Neovascularization and Angiogenic Gene Expression Following Chronic Arsenic Exposure in Mice. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2005, 5, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmignani, M.; Boscolo, P.; Iannaccone, A. Effects of Chronic Exposure to Arsenate on the Cardiovascular Function of Rats. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1983, 40, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Shan, H.; Zhao, J.; Hong, Y.; Bai, Y.; Sun, I.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Du, Z. L-Type Calcium Current (ICa,L) and Inward Rectifier Potassium Current (IK1) Are Involved in QT Prolongation Induced by Arsenic Trioxide in Rat. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 26, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbey, J.T.; Pezzullo, J.C.; Soignet, S.L. Effect of Arsenic Trioxide on QT Interval in Patients with Advanced Malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3609–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumford, J.L.; Wu, K.; Xia, Y.; Kwok, R.; Yang, Z.; Foster, J.; Sanders, W.E. Chronic Arsenic Exposure and Cardiac Repolarization Abnormalities with QT Interval Prolongation in a Population-Based Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.-H.; Chong, C.-K.; Tseng, C.-P.; Hsueh, Y.-M.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Tseng, C.-C.; Chen, C.-J. Long-Term Arsenic Exposure and Ischemic Heart Disease in Arseniasis-Hyperendemic Villages in Taiwan. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 137, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Chiou, H.Y.; Chiang, M.H.; Lin, L.J.; Tai, T.Y. Dose-Response Relationship between Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality and Long-Term Arsenic Exposure. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, P.; Sinha, M.; Sil, P.C. Arsenic-Induced Oxidative Myocardial Injury: Protective Role of Arjunolic Acid. Arch. Toxicol. 2008, 82, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Han, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ma, W.; Ding, F.; Zhang, L.; Yu, M.; Liu, S.; et al. Arsenic Trioxide Blocked Proliferation and Cardiomyocyte Differentiation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Implication in Cardiac Developmental Toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 309, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Wang, S.-L.; Chiou, J.-M.; Tseng, C.-H.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Hsueh, Y.-M.; Chen, S.-Y.; Wu, M.-M.; Lai, M.-S. Arsenic and Diabetes and Hypertension in Human Populations: A Review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007, 222, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.Y.; Umans, J.G.; Yeh, F.; Francesconi, K.A.; Goessler, W.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Guallar, E.; Howard, B.V.; Weaver, V.M.; et al. The Association of Urine Arsenic with Prevalent and Incident Chronic Kidney Disease: Evidence from the Strong Heart Study. Epidemiology 2015, 26, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.A.; Cassano, V.A.; Murray, C.; ACOEM Task Force on Arsenic Exposure. Arsenic Exposure, Assessment, Toxicity, Diagnosis, and Management: Guidance for Occupational and Environmental Physicians. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e634–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, N. (Ed.) Introduction to Remediation of Arsenic Toxicity: Application of Biological Treatment Methods for Remediation of Arsenic Toxicity from Groundwaters. In Arsenic Toxicity; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Cai, Y.; O’Driscoll, N.; Liu, G.; Cai, Y.; O’Driscoll, N. Overview of Mercury in the Environment. In Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology of Mercury; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Feng, X.; Li, P.; Yin, R.; Yu, B.; Sonke, J.E.; Guinot, B.; Anderson, C.W.N.; Maurice, L. Use of Mercury Isotopes to Quantify Mercury Exposure Sources in Inland Populations, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5407–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D. Fish, Mercury, Selenium and Cardiovascular Risk: Current Evidence and Unanswered Questions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 1894–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.F.; Lowe, M.; Chan, H.M. Mercury Exposure, Cardiovascular Disease, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downer, M.K.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Stampfer, M.; Warnberg, J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Ros, E.; Fitó, M.; et al. Mercury Exposure and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Nested Case-Control Study in the PREDIMED (PREvention with MEDiterranean Diet) Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Shi, P.; Morris, J.S.; Spiegelman, D.; Grandjean, P.; Siscovick, D.S.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B. Mercury Exposure and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Two U.S. Cohorts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M.C. Role of Mercury Toxicity in Hypertension, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2011, 13, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Bi, K.-D.; Fan, Y.-M.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhang, J.-W.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, F.-L.; Dong, J.-X. In Vitro Modulation of Mercury-Induced Rat Liver Mitochondria Dysfunction. Toxicol. Res. 2018, 7, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobal, A.B.; Horvat, M.; Prezelj, M.; Briski, A.S.; Krsnik, M.; Dizdarevic, T.; Mazej, D.; Falnoga, I.; Stibilj, V.; Arneric, N.; et al. The Impact of Long-Term Past Exposure to Elemental Mercury on Antioxidative Capacity and Lipid Peroxidation in Mercury Miners. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2004, 17, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppänen, K.; Soininen, P.; Salonen, J.T.; Lötjönen, S.; Laatikainen, R. Does Mercury Promote Lipid Peroxidation? An In Vitro Study Concerning Mercury, Copper, and Iron in Peroxidation of Low-Density Lipoprotein. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004, 101, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Afshari, R.; Mehrpour, O.; Samarghandian, S. Mercury and Atherosclerosis: Cell Biology, Pathophysiology, and Epidemiological Studies. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 196, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, J.T.; Seppänen, K.; Lakka, T.A.; Salonen, R.; Kaplan, G.A. Mercury Accumulation and Accelerated Progression of Carotid Atherosclerosis: A Population-Based Prospective 4-Year Follow-up Study in Men in Eastern Finland. Atherosclerosis 2000, 148, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbi, S.; Oberholzer, H.M.; Van Rooy, M.J.; Venter, C.; Bester, M.J. Effects of Chronic Exposure to Mercury and Cadmium Alone and in Combination on the Coagulation System of Sprague-Dawley Rats. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2017, 41, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, V.G. Lethal Concentrations of Mercury or Lead Do Not Affect Coagulation Kinetics in Human Plasma. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2019, 48, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, E.M.; Vassallo, D.V. Effects of Mercury on the Contractility of Isolated Rat Cardiac Muscle. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1992, 25, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, B.; Dewailly, E.; Poirier, P.; Counil, E.; Suhas, E. Influence of Mercury Exposure on Blood Pressure, Resting Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability in French Polynesians: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health 2011, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillion, M.; Mergler, D.; Sousa Passos, C.J.; Larribe, F.; Lemire, M.; Guimarães, J.R.D. A Preliminary Study of Mercury Exposure and Blood Pressure in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Health 2006, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, B.; Dewailly, E.; Poirier, P. Cardiac Autonomic Activity and Blood Pressure among Nunavik Inuit Adults Exposed to Environmental Mercury: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Health 2008, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Lee, S.; Basu, N.; Franzblau, A. Associations of Blood and Urinary Mercury with Hypertension in U.S. Adults: The NHANES 2003–2006. Environ. Res. 2013, 123, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, M.; Strömberg, U.; Bergdahl, I.A.; Jansson, J.-H.; Kauhanen, J.; Norberg, M.; Salonen, J.T.; Skerfving, S.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Vessby, B.; et al. Myocardial Infarction in Relation to Mercury and Fatty Acids from Fish: A Risk-Benefit Analysis Based on Pooled Finnish and Swedish Data in Men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guallar, E.; Sanz-Gallardo, M.I.; van’t Veer, P.; Bode, P.; Aro, A.; Gómez-Aracena, J.; Kark, J.D.; Riemersma, R.A.; Martín-Moreno, J.M.; Kok, F.J.; et al. Mercury, Fish Oils, and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Rimm, E.B. Fish Intake, Contaminants, and Human Health: Evaluating the Risks and the Benefits. JAMA 2006, 296, 1885–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M.C. The Role of Mercury and Cadmium in Cardiovascular Disease, Hypertension, and Stroke. In Metal Ion in Stroke; Springer Series in Translational Stroke Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.D.; Rai, A.N.; Hardiek, M.L. Mercury Intoxication and Arterial Hypertension: Report of Two Patients and Review of the Literature. Pediatrics 2000, 105, E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etteieb, S.; Magdouli, S.; Zolfaghari, M.; Brar, S. Monitoring and Analysis of Selenium as an Emerging Contaminant in Mining Industry: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mateo, G.; Navas-Acien, A.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Guallar, E. Selenium and Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomer, N.; Grote Beverborg, N.; Hoes, M.F.; Streng, K.W.; Vermeer, M.; Dokter, M.M.; IJmker, J.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Hillege, H.L.; et al. Selenium and Outcome in Heart Failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mubarak, A.A.; Grote Beverborg, N.; Suthahar, N.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Touw, D.J.; de Boer, R.A.; van der Meer, P.; Bomer, N. High Selenium Levels Associate with Reduced Risk of Mortality and New-Onset Heart Failure: Data from PREVEND. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Guo, K.; Zhang, C.; Talukder, M.; Lv, M.-W.; Li, J.-Y.; Li, J.-L. Comparison of Nanoparticle-Selenium, Selenium-Enriched Yeast and Sodium Selenite on the Alleviation of Cadmium-Induced Inflammation via NF-kB/IκB Pathway in Heart. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-W.; Chang, H.-H.; Yang, K.-C.; Chiang, C.-H.; Yao, C.-A.; Huang, K.-C. Gender Differences with Dose− Response Relationship between Serum Selenium Levels and Metabolic Syndrome-A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retondario, A.; Fernandes, R.; Rockenbach, G.; Alves, M. de A.; Bricarello, L.P.; de Moraes Trindade, E.B.S.; de Assis Guedes de Vasconcelos, F. Selenium Intake and Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastola, M.M.; Locatis, C.; Maisiak, R.; Fontelo, P. Selenium, Copper, Zinc and Hypertension: An Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011–2016). BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, P.M.; Adams, W.J.; Brooks, M. Ecological Assessment of Selenium in the Aquatic Environment; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafadeen Amuda, O.; Olanrewaju Alade, A.; Hung, Y.-T.; Wang, L.K.; Sung Wang, M.-H. Toxicity, Sources, and Control of Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), Molybdenum (Mo), Silver (Ag), and Rare Earth Elements in the Environment. In Handbook of Advanced Industrial and Hazardous Wastes Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, H.; Wessler, J.D.; Gupta, A.; Maurer, M.S.; Bikdeli, B. Zinc Deficiency and Heart Failure: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Yao, W.; Wu, X.; Huang, J.; Bian, B. The Relationship between Serum Zinc Level and Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2739014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efeovbokhan, N.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Ahokas, R.A.; Sun, Y.; Guntaka, R.V.; Gerling, I.C.; Weber, K.T. Zinc and the Prooxidant Heart Failure Phenotype. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 64, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannam, M.; Abdelhalim, M.; Moussa, S.; AL-Mohy, Y.; Al-Ayed, M. Ultraviolet-Visible and Fluorescence Spectroscopy Techniques Are Important Diagnostic Tools during the Progression of Atherosclerosis: Diet Zinc Supplementation Retarded or Delayed Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, e121–e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, Y.; Wang, T. Investigating the Role of Zinc in Atherosclerosis: A Review. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Laukkanen, J.A. Serum Zinc Concentrations and Incident Hypertension: New Findings from a Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.R.; Mistry, M.; Cheriyan, A.M.; Williams, J.M.; Naraine, M.K.; Ellis, C.L.; Mallick, R.; Mistry, A.C.; Gooch, J.L.; Ko, B.; et al. Zinc Deficiency Induces Hypertension by Promoting Renal Na+ Reabsorption. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 316, F646–F653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Man, Q.; Song, P.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, L. Association of Whole Blood Copper, Magnesium and Zinc Levels with Metabolic Syndrome Components in 6-12-Year-Old Rural Chinese Children: 2010-2012 China National Nutrition and Health Survey. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruz, M.; Carrasco, F.; Rojas, P.; Basfi-Fer, K.; Hernández, M.C.; Pérez, A. Nutritional Effects of Zinc on Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: Mechanisms and Main Findings in Human Studies. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 188, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Nejdl, L.; Gumulec, J.; Zitka, O.; Masarik, M.; Eckschlager, T.; Stiborova, M.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R. The Role of Metallothionein in Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6044–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetke, L.M.; Chow, C.K. Copper Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidant Nutrients. Toxicology 2003, 189, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, F.J.; van Duijn, C.M.; Hofman, a.; van Der Voet, G.B.; de Wolff, F.A.; Paays, C.H.C.; Valkenburg, H.A. Serum copper and zinc and the risk of death from cancer and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1988, 128, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wu, Y.; Hartiala, J.; Fan, Y.; Stewart, A.F.R.; Roberts, R.; McPherson, R.; Fox, P.L.; Allayee, H.; Hazen, S.L. Clinical and Genetic Association of Serum Ceruloplasmin with Cardiovascular Risk. Arterioscler. Thromb Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, N.; Courbon, D.; Ducimetiere, P.; Zureik, M. Zinc, Copper, and Magnesium and Risks for All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality. Epidemiology 2006, 17, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S. Serum Copper Concentration and Coronary Heart Disease among US Adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Sarkar, P.D.; Paneri, S.; Lohokare, R.; Agrawal, T.; Manyal, R. Elevated Serum Ceruloplasmin Level in Patients of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2022, 32 (Suppl. S1), S115. [Google Scholar]

- Reunanen, A.; Knekt, P.; Aaran, R.K. Serum Ceruloplasmin Level and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Stroke. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 136, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Hanć, A.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Rodzki, M.; Witkowska, A.; Michalak, M.; Perek, B.; Haneya, A.; Jemielity, M. Serum Copper Concentration Reflect Inflammatory Activation in the Complex Coronary Artery Disease—A Pilot Study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2022, 74, 127064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, B.; Aslan, S.; Bedir, A.; Alvur, M. The Interaction between Copper and Coronary Risk Indicators. Jpn. Heart J. 2001, 42, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aneja, A.; Tang, W.H.W.; Bansilal, S.; Garcia, M.J.; Farkouh, M.E. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Insights into Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Challenges, and Therapeutic Options. Am. J. Med. 2008, 121, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Pontré, B.; Pickup, S.; Choong, S.Y.; Li, M.; Xu, H.; Gamble, G.D.; Phillips, A.R.J.; Cowan, B.R.; Young, A.A.; et al. Treatment with a Copper-Selective Chelator Causes Substantive Improvement in Cardiac Function of Diabetic Rats with Left-Ventricular Impairment. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2013, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koşar, F.; Sahin, I.; Taşkapan, C.; Küçükbay, Z.; Güllü, H.; Taşkapan, H.; Cehreli, S. Trace Element Status (Se, Zn, Cu) in Heart Failure. Anadolu Kardiyol. Derg. 2006, 6, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Shokrzadeh, M.; Ghaemian, A.; Salehifar, E.; Aliakbari, S.; Saravi, S.S.S.; Ebrahimi, P. Serum Zinc and Copper Levels in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Biol Trace Elem Res 2009, 127, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Málek, F.; Dvorák, J.; Jiresová, E.; Spacek, R. Difference of Baseline Serum Copper Levels between Groups of Patients with Different One Year Mortality and Morbidity and Chronic Heart Failure. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2003, 11, 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Shen, R.; Huang, L.; Yu, J.; Rong, H. Association between Serum Copper and Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 28, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.J.; Hill, J.A. Copper Futures: Ceruloplasmin and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1678–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastoulis, E.; Karakasi, M.V.; Couvaris, C.M.; Kapetanakis, S.; Fiska, A.; Pavlidis, P. Greenish-Blue Gastric Content: Literature Review and Case Report on Acute Copper Sulphate Poisoning. Forensic Sci. Rev. 2017, 29, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

| Metals | Sources | Prevention Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Lead | House paint, gasoline, cosmetics and medications, lead glazed ceramics, lead utensils, lead water pipes | Routine blood lead monitoring in vulnerable communities, lead pipe and paint replacement, regulations improving lead levels requirements in gasoline, improving awareness and manufacturing processes to avoid using lead |

| Barium | Water contamination. Ingestion of contaminated food. | Improved studies to determine appropriate thresholds for barium toxicity |

| Nickel | Drinking water, food, and soil contamination. Environmental pollution in fuels, industry, and waste products. | EPA monitoring of occupational nickel and water nickel exposure. More studies to determine toxicity |

| Chromium | Natural trace amounts in most living creatures. Leather tanning, textile dying, paint pigmenting, wood preservation, and metal plating whose waste products cause water, soil, and food contamination. Low level airborne exposure in subway systems and the above occupations. | Improvement of occupational safety standards and improved waste disposal standards. Soil–plant barriers near dumping sites that use chromium avid plants to absorb and reduce chromium into less toxic forms. |

| Cadmium | Zinc and lead ores. Phosphate fertilizers. Ingested through contamination of food and water. Occupational exposure in smelting, battery, and pigment production industries. Cigarette smoke. | Smoking/tobacco use reduction. Aggressive strategies to monitor of food and water sources and prevention of use of contaminated sources. Aggressive regulation to prevent cadmium dumping in associated industries. |

| Arsenic | Drinking water contaminated through natural processes such as weathering or volcanic eruption, and through smelting, mining, or the use of pesticides and herbicides. | Groundwater cleansing through microfiltration, the use of plants to accumulate toxin, or processes involving adsorption of biologically generated iron and manganese oxides. Increasing awareness and limiting use of contaminated water sources. Decreased use of tobacco products. |

| Mercury | Natural occurrence through volcanic activity, geothermal activity, volatilization of oceanic mercury, and emissions from soil with naturally elevated mercury. Gold smelting, cement production, and waste incineration. Most human exposure through consumption of plants and animals, especially fish, in which the toxin has accumulated. | Improved industrial processes and waste handling to limit mercury contamination of the environment. Close monitoring of dietary lead levels and increased public awareness and avoidance of contaminated food sources. |

| Selenium | Contaminate of sulfur containing minerals released naturally through volcanic activity and weathering. Anthropogenic sources include mining, fossil fuel refinement, and agricultural irrigation. | Improved mining and agricultural runoff management. |

| Zinc | Widely dispersed in food, water, and air. Metal coating, battery cells, and pennies. Mining and refining, coal burning, and burning of waste products. | Occupational safety standards, monitoring of food and water supplies for excess zinc, and enhanced recycling processes. |

| Copper | Coins, wiring, pipes, ceramics, glaze, glass works, electronics, fungicides/herbicides, lumber preservation, textiles, tanned goods. Soil and water contamination through smelting, incinerating, powerplants, and water treatment to remove algae. Prolonged TPN, hemodialysis. | Improved filtration and recycling techniques, improved regulation of the use of fungicides and herbicide, and improved runoff management. Close monitoring of copper in certain patient’s such as those on hemodialysis or undergoing prolonged TPN use are especially useful. |

| Lead | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study Population | Findings | Limitations |

| Schober SE, Mirel LB, Graubard BI, Brody DJ, Flegal KM. from ref. [17] | Cohort | 9757 participants 40+ years old from the NHANES study | “Using blood lead levels < 5 µg/dL as the referent, we determined that the relative risk of mortality from all causes was 1.24 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.05–1.48] for those with blood levels of 5–9 µg/dL and 1.59 (95% CI, 1.28–1.98) for those with blood levels ≥ 10 µg/dL (p for trend < 0.001). For all ages combined, the estimated relative risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease was 1.20 (95% CI, 0.93–1.55) for those with blood lead levels of 5–9 μg/dL and 1.55 (95% CI, 1.16–2.07) for those with blood lead levels of ≥10 μg/dL (test for trend, p < 0.01)” | Observational study, Population restricted USA, only one lead level used (not able to differentiate acute from chronic/continuous exposure), socioeconomic status (SES) confounders may not be fully accounted for (study used education and family income) |

| Navas-Acien A, Selvin E, Sharrett AR, Calderon-Aranda E, Silbergeld E, Guallar E. from ref. [19] | Cross Sectional | 2125 participants 40+ years old in the 1999–2000 NHANES survey | “After adjustment for demographic and cardiovascular risk factors, the Odds ratios (ORs) of peripheral arterial disease comparing quartiles 2 to 4 of lead with the lowest quartile were 1.63 (95% CI, 0.51 to 5.15), 1.92 (95% CI, 0.62 to 9.47), and 2.88 (95% CI, 0.87 to 9.47), respectively (p for trend = 0.02). The corresponding ORs for cadmium were 1.07 (95% CI, 0.44 to 2.60), 1.30 (95% CI, 0.69 to 2.44), and 2.82 (95% CI, 1.36 to 5.85), respectively (p for trend = 0.01). The OR of peripheral arterial disease for current smokers compared with never smokers was 4.13. Adjustment for lead reduced this OR to 3.38, and adjustment for cadmium reduced it to 1.84.” | Observational Study, Population restricted to US, possible confounding by SES or other unmeasured pollutants, single blood measurements were used for lead and cadmium, study only able to assess prevalent, not incident cases of PAD |

| Pocock SJ, Shaper AG, Ashby D, Delves HT, Clayton BE. from ref. [20] | Cross Sectional + Cohort | 7371 men aged 40–59 from 24 British towns | “Cross-sectional data indicate that an estimated mean increase of 1.45 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure occurs for every doubling of blood lead concentration with a 95% confidence interval of 0.47 to 2.43 mm Hg. After 6 years of follow-up, 316 of these men had major ischemic heart disease, and 66 had a stroke. After allowance for the confounding effects of cigarette smoking and town of residence there is no evidence that blood lead is a risk factor for these cardiovascular events.” | Observational study, population restricted to British men, not all confounders possibly accounted for. |

| Cheng Y, Schwartz J, Vokonas PS, Weiss ST, Aro A, Hu H. from ref. [23] | Cross Sectional | 775 men who participated in the Normative Aging Study (age 48–93) | “Bone lead levels were found to be positively associated with heart rate– corrected QT and QRS intervals, especially in younger men. Specifically, in men < 65 years of age, a 10 μg/g increase in tibia lead was associated with an increase in the QT interval of 5.03 ms (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.83 to 9.22) and with an increase in the QRS interval of 4.83 ms (95% CI, 1.83 to 7.83) in multivariate regression models. In addition, an elevated bone lead level was found to be positively associated with an increased risk of intraventricular block in men < 65 years of age and with an increased risk of atrioventricular (AV) block in men ≥ 65 years of age. After adjustment for age and for serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level, a 10 μg/g increase in tibia lead was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.23 (95% CI, 1.28 to 3.90) for intraventricular block in men < 65 years of age and with an OR of 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.47) for AV block in men ≥ 65 years of age. Blood lead level was not associated with any of the electrocardiogram (ECG) outcomes examined.” | Observational Study, population restricted to men from the Boston area (USA), only 1 cumulative bone-lead measurement taken |

| Navas-Acien A, Guallar E, Silbergeld EK, Rothenberg SJ. from ref. [24] | Systematic Review | 12 studies of lead and CVD in general populations, 18 studies of lead and CVD mortality in occupational populations, and 5 studies of lead and intermediate cardiovascular outcomes | “A positive association of lead exposure with blood pressure has been identified in numerous studies in different settings, including prospective studies and in relatively homogeneous socioeconomic status groups. Several studies have identified a dose-response relationship. Although the magnitude of this association is modest, it may be underestimated by measurement error. The hypertensive effects of lead have been confirmed in experimental models. Beyond hypertension, studies in general populations have identified a positive association of lead exposure with clinical cardiovascular outcomes (cardiovascular, coronary heart disease, and stroke mortality; and peripheral arterial disease), but the number of studies is small. In some studies these associations were observed at blood lead levels < 5 µg/dL.” | Largely based on observational studies, quantitative analysis limited |

| Barium | ||||

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study population | Findings | Limitations |

| Wones RG, Stadler BL, Frohman LA. from ref. [28] | Experimental Trial | 11 men | “There were no changes in morning or evening systolic or diastolic blood pressures, plasma cholesterol or lipoprotein or apolipoprotein levels, serum potassium or glucose levels, or urine catecholamine levels. There were no arrythmias related to barium exposure detected on continuous electrocardiographic monitoring. A trend was seen toward increased total serum calcium levels with exposure to barium, which was of borderline statistical significance and of doubtful clinical significance. In summary, drinking water barium at levels of 5 and 10 ppm did not appear to affect any of the known modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.” | Extremely small sample size, no control group, barium-only study at very dilute exposure concentrations over very short period of time, subjects allowed to drink infinite distilled water after completing daily dose of barium-laced water |

| Perry HM Jr, Kopp SJ, Perry EF, Erlanger MW. from ref. [29] | Experimental animal study | 195 Long–Evans rats | “Average systolic pressure increased significantly after exposure to 100 ppm barium for 1 mo or longer and after exposure to 10 ppm barium for 8 mo or longer. After 4 or 76 mo, barium exposure failed to alter organ weights or tissue concentrations of calcium, magnesium, sodium, or potassium; however, both 10 and 100 ppm barium resulted in significant increases in tissue barium. Rats exposed to 100 ppm Ba for 16 mo exhibited depressed rates of cardiac contraction and depressed electrical excitability in the heart. Hearts from these maximally exposed rats also had significantly lower ATP content and phosphorylation potential, as measured by 31 P NMR spectros-copy.” | Animal study, relatively small sample size |

| Brenniman GR, Namekata T, Kojola WH, Carnow BW, Levy PS. from ref. [30] | Retrospective cohort | Communities in Illinois between 1971–1975 | “Results of this mortality study revealed that the high barium communities had significantly higher (p < 0.05) death rates for “all cardiovascular diseases” and “heart disease” compared to the low barium communities. | Observational study, population restricted to Illinois cities, many possible confounders that were not controlled for (e.g., differentials in population change, water softener use, etc.) |

| Nickel | ||||

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study population | Findings | Limitations |

| Zhang N, Chen M, Li J, Deng Y, Li SL, Guo YX, Li N, Lin Y, Yu P, Liu Z, Zhu J. from ref. [35] | Case-Control | 399 cases (pregnant women with fetal congenital heart disease (CHD)) and 490 controls (pregnant females without fetal CHD) | The median concentrations of nickel were 0.629 ng/mg, p < 0.05 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.326; 95% CI, 1.003–1.757) and 0.178 ng/mg, p < 0.05 (aOR, 2.204; 95% CI, 0.783–6.206), in maternal hair and in fetal placental tissue in the CHD group, respectively. Significant differences in the level of nickel in hair were also found in the different CHD subtypes including septal defects (p < 0.05), conotruncal defects (p < 0.05), right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (p < 0.01), and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (p < 0.05). Dramatically different nickel concentrations in fetal placenta tissue were found in cases with other heart defects (p < 0.05).” | Observational study, Restricted to Chinese women, unknown how well placental or maternal hair nickel levels actually correspond to fetal exposure, possible confounding with toxic effects from other metals |

| Cheek, J., Fox, S.S., Lehmler, HJ. et al. from ref. [39] | Cross Sectional | 2739 adults 18+ years old from the NHANES 2017–20 | “Urinary nickel concentrations were higher in individuals with CVD (weighted median 1.34 μg/L) compared to those without CVD (1.08 μg/L). After adjustment for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and other risk factors for CVD, the ORs (95% CIs) for CVD compared with the lowest quartile of urinary nickel were 3.57 (1.73–7.36) for the second quartile, 3.61 (1.83–7.13) for the third quartile, and 2.40 (1.03–5.59) for the fourth quartile. Cubic spline regression revealed a non-monotonic, inverse U-shaped, association between urinary nickel and CVD (Pnonlinearity < 0.001).” | Observational study, population restricted to US adults, only used one spot urinary nickel sample |

| Lind, P. M., Olsén, L., and Lind, L. from ref. [40] | Cross Sectional | 1016 adults aged 70 in the Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study | “Nickel levels were related to the number of carotid arteries with plaques in an inverted U-shaped manner after multiple adjustment for gender, waist circumference, body mass index, fasting blood glucose, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL and LDL cholesterol, serum triglycerides, smoking, antihypertensive treatment and statin use (p = 0.026).” | Observational study, population limited to Caucasians from the PIVUS study aged 70, study had a moderate participation rate that may have led to some mild bias |

| Shi, P., Liu, S., Xia, X., Qian, J., Jing, H., Yuan, J., Zhao, H., Wang, F., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, X., He, M., and Xi, S. from ref. [41] | Cross Sectional | 865 participants from 6 factories in northeastern China | “A Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression indicated a hormetic triphasic dose-response relationship between eight urinary metals (Co, Cr, Ni, Cd, As, Fe, Zn, and Pb) and hypertension.” | Observational Study, population restricted to male factory workers in one region of northeastern China, only one urinary metal measurement was performed, hypertension status based on self-report and single laboratory measurement, antihypertensive medication use not considered |

| Chromium | ||||

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study population | Findings | Limitations |

| Bai, J., Xun, P., Morris, S., Jacobs, J., Liu, K., and He, K. from ref. [48] | Retrospective Cohort | 3648 adults from CARDIA study, age 20–32 years | “multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval [CI]) of metabolic syndrome comparing the highest to the lowest quartiles of toenail chromium levels was 0.80 (0.66–0.98; Plinear trend = 0.006). The adjusted HRs were 0.82 (0.68–0.98; Ptrend = 0.045) for having abnormal triglycerides levels and 0.75 (0.64–0.88; Ptrend = 0.030) for having abnormal HDL cholesterol levels.” | Observational study, chromium only measured once at beginning of study, population recruited from urban areas of the USA |

| Chen, J., Kan, M., Ratnasekera, P., Deol, L. K., Thakkar, V., and Davison, K. from ref. [49] | Cross Sectional | 2982 adults 40+ years of age from 2016 NHES survey | “The odds of CVDs were 1.89 times higher for males who had blood chromium levels < 0.7 μg/L (aOR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.24–2.90) compared to those who had levels within the normal range. Males who had low blood chromium levels (aOR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.21–0.74) had lower odds of depression compared to those with normal blood chromium levels. The odds of diabetes mellitus (DM) was 2.58 times higher for males and 1.99 times higher for females with low blood chromium levels compared to those with normal blood chromium levels (aOR = 2.58 (male), 1.99 (female), p’s < 0.001).” | Observational study, no longitudinal data, population restricted to noninstitutionalized civilian resident population of USA |

| Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M., Martínez-González, M. Á., Muñoz-Bravo, C., Ruiz-Canela, M., Mariscal, A., Salas-Salvadó, J., Estruch, R., Corella, D., Arós, F., Fito, M., Lapetra, J., Serra-Majem, L., Pintó, X., Alonso-Gómez, Á., Portoles, O., Fiol, M., Bulló, M., Castañer, O., Ros, E., and Gómez-Gracia, E. from ref. [50] | Nested Case-Control | 147 Cases with CVD, 271 Controls | “The fully adjusted OR for the highest vs. lowest quartile of toenail Cr was 0.54 (95% CI: 0.26–1.14; Ptrend = 0.189) for the nested case-control study. On stratification for diabetes mellitus (DM), OR was 1.37 (95% CI: 0.54–3.46; Ptrend = 0.364) for the DM group, and 0.25 (95% CI: 0.08–0.80; Ptrend = 0.030) for the non-DM group (p for interaction = 0.078).” | Observational Study, chromium only measured once at beginning of study, population restricted to Spanish Adults aged 55–80, sample size relatively small |

| Guallar, E., Jiménez, F. J., van ’t Veer, P., Bode, P., Riemersma, R. A., Gómez-Aracena, J., Kark, J. D., Arab, L., Kok, F. J., and Martín-Moreno, J. M. from ref. [52] | Case-Control Study | 684 male cases with first time MI, 724 male controls | “Average toenail chromium concentrations were 1.10 μg/g in cases (95% confidence interval: 1.01, 1.18) and 1.30 μg/g in controls (95% CI: 1.21, 1.40). Multivariate odds ratios for quintiles 2–5 were 0.82 (95% CI: 0.52, 1.31), 0.68 (95% CI: 0.43, 1.08), 0.60 (95% CI: 0.37, 0.97), and 0.59 (95% CI: 0.37, 0.95).” | Observational Study, Males studied only, chromium measured only once at the start of the study, population restricted to men form 8 European countries and Israel, only studied nonfatal MI |

| ROEBACK, J. R., HLA, K. M., CHAMBLESS, L. E., and FLETCHER, R. H. from ref. [53] | Randomized Control Trial | 72 men receiving beta blockers (63, 88%, completed the study) | “After 8-week treatment phase of total daily chromium dose of 600 micrograms in 3 daily doses, mean baseline levels of HDL and total cholesterol (±SD) were 0.93 ± 0.28 mmol/L and 6.0 ± 1.0 mmol/L (36 ± 11.1 mg/dL and 232 ± 38.5 mg/dL), respectively. The difference between groups in adjusted mean change in HDL cholesterol levels, accounting for baseline HDL cholesterol levels, age, weight change, and baseline total cholesterol levels, was 0.15 mmol/L (5.8 mg/dL) (p = 0.01) with a 95% Cl showing that the treatment effect was greater than +0.04 mmol/L (+1.4 mg/dL). Mean total cholesterol, triglycerides and body weight did not change significantly during treatment for either group. Compliance as measured by pill count was 85%, and few side effects were reported. Two months after the end of treatment, the between-group difference in adjusted mean change from baseline to end of post-treatment follow-up was −0.003 mmol/L (−0.1 mg/dL).” | Restricted to males on beta blockers at a single VA medical center (Durham VAMC). Some significant differences in treatment vs. placebo group (e.g., 49% of placebo reported alcohol use compared to just 29% in treatment group; 26% of treatment group was post-MI vs. just 11% of placebo group) |

| Price Evans, D. A., Tariq, M., Dafterdar, R., Al Hussaini, H., and Sobki, S. H. from ref. [54] | Randomized control trial–Animal Study | 20 male adult New Zealand white Rabbits (4 normal diet, 8 high cholesterol diet w/IM NaCl, 8 with high cholesterol diet w/IM CrCl3) | “The size of lipid deposits in the coronary vasculature of the hypercholesterolemic rabbits were greatly reduced after intramuscular chromium chloride injections. Lipid deposits in the ascending aorta were similarly reduced, as well as the serum cholesterol concentrations. The terminal serum chromium concentrations in the chromium-treated group were in the range of 3258–4513 μg/L, whereas, in the untreated animals, the concentrations were 3.2 to 6.3 μg/L. The general condition of the chromium-treated animals was good and they were continuing to gain weight up to the time they were killed. Liver function tests had become abnormal even though there was no evidence of hepatic histopathological lesions specifically affecting the chromium-treated group. The kidney function tests and histopathology were normal.” | Animal study, very small sample size |

| Cadmium | ||||

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study population | Findings | Limitations |

| Menke, A., Muntner, P., Silbergeld, E. K., Platz, E. A., and Guallar, E. from ref. [64] | Retrospective Cohort | 13,958 NHANES III participants | “After multivariable adjustment, the hazard ratios [95% confidence interval (CI)] for all-cause, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease mortality associated with a 2-fold higher creatinine-corrected urinary cadmium were, respectively, 1.28 (95% CI, 1.15–1.43), 1.55 (95% CI, 1.21–1.98), 1.21 (95% CI, 1.07–1.36), and 1.36 (95% CI, 1.11–1.66) for men and 1.06 (95% CI, 0.96–1.16), 1.07 (95% CI, 0.85–1.35), 0.93 (95% CI, 0.84–1.04), and 0.82 (95% CI, 0.76–0.89) for women.” | Observational study, Population restricted to civilian noninstitutionalized adults in the USA, use of single spot urine cadmium samples, possible confounding by smoking status (though adjusted for smoking status and pack years and results were similar for the subgroup analysis of never-smoking men) |

| Messner, B., Knoflach, M., Seubert, A., Ritsch, A., Pfaller, K., Henderson, B., Shen, Y. H., Zeller, I., Willeit, J., Laufer, G., Wick, G., Kiechl, S., and Bernhard, D. from ref. [74] | Human Cross Sectional and Animal Randomized Control Trial | 195 healthy women age 18–22 in the Atherosclerosis Risk Factors in Female Youngsters (ARFY) study; Female ApoE KO mice (number not stated) | “In the young women, cadmium (Cd) level was independently associated with early atherosclerotic vessel wall thickening (intima-media thickness exceeding the 90th percentile of the distribution; multivariable OR 1.6 [1.1.–2.3], p = 0.016). In line, Cd-fed Apolipoprotein E knockout mice yielded a significantly increased aortic plaque surface compared to controls (9.5 versus 26.0 mm, p < 0.004).” | Smaller sample size, human part of study observational, only females tested, clinical significance of findings uncertain as patient outcomes were not charted over time |

| Eum, K.-D., Lee, M.-S., and Paek, D. from ref. [78] | Cross Sectional | 958 men and 944 women in the 2005 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) | “After adjusting for covariates, the odds ratio of hypertension comparing the highest to the lowest tertile of cadmium in blood was 1.51 (95% confidence interval 1.13 to 2.05), and a dose–response relationship was observed. Systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure were all positively associated with blood cadmium level, and this effect of cadmium on blood pressure was markedly stronger when the kidney function was reduced.” | Observational Study, Population restricted to Korean adults, only a single measurement of cadmium was taken at one point in time. |

| Maria Tellez-Plaza, Navas-Acien, A., Crainiceanu, C. M., and Guallar, E. from ref. [79] | Cross Sectional | US adults NHANES participants with blood (n = 10,991) and urine (n = 3496) cadmium levels recorded | “After multivariable adjustment, the average differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure comparing participants in the 90th vs. 10th percentile of the blood cadmium distribution were 1.36 mmHg [95% confidence interval (CI), −0.28 to 3.00] and 1.68 mmHg (95% CI, 0.57–2.78), respectively. The corresponding differences were 2.35 mmHg and 3.27 mmHg among never smokers, 1.69 mmHg and 1.55 mmHg among former smokers, and 0.02 mmHg and 0.69 mmHg among current smokers. No association was observed for urine cadmium with blood pressure levels, or for blood and urine cadmium with the prevalence of hypertension.” | Observational study, restricted to US adults >20 years, only single blood and urine measurements of cadmium were made, most participants had blood cadmium levels close to the limit of detection |

| Arsenic | ||||

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study population | Findings | Limitations |

| Hsieh, Y.-C., Hsieh, F.-I., Lien, L.-M., Chou, Y.-L., Chiou, H.-Y., and Chen, C.-J. from ref. [98] | Case-Control | 479 residents (235 cases, 244 controls) from Noretheastern Taiwan | “Significant crude and age-and-gender adjusted odds ratios [CI] for Atherosclerosis in those exposed to elevated concentrations of Arsenic > 50 μg/L in well water (crude: 2.0 [1.1–3.8] Ptrend = 0.0054, adjusted 2.4 [1.2–4.6] Ptrend = 0.0049) and for those with cumulative arsenic exposure > 1.1 mg/L/year (crude: 1.6 [1.0–26], adjusted 1.9 [1.1–3.1]).” | Observational study, family history of stroke and CVD not included, used arsenic in well water instead of direct urinary/serum arsenic measurements, population restricted to Taiwanese citizens, did not norm exposures by body weight |

| Wang, Y.-H., Wu, M.-M., Hong, C.-T., Lien, L.-M., Hsieh, Y.-C., Tseng, H.-P., Chang, S.-F., Su, C.-L., Chiou, H.-Y., and Chen, C.-J. from ref. [99] | Case-Control | 605 resident (289 men, 316 women) from Northeastern Taiwan | “A significant age-and gender-adjusted odds ratio of 3.3 for the development of carotid atherosclerosis was observed among the high-arsenic exposure group who drank well water containing arsenic at levels > 50 μg/L.” | Observational Study, population restricted to Taiwanese citizens, info on familial history of stroke, CVD, and LDL were not collected, used arsenic in well water instead of direct urinary/serum arsenic measurements |

| Mumford, J. L., Kegong Wu, Xia, Y., Richard Kwok, Zhihui Yang, Foster, J., and William E. Sanders Jr. from ref. [108] | Cross Sectional | 313 residents from Ba Men, Inner Mongolia | “The prevalence rates of QT prolongation and water arsenic concentrations showed a dose-dependent relationship (p = 0.001). The prevalence rates of QTc prolongation were 3.9, 11.1, 20.6% for low, medium, and high arsenic exposure, respectively. QTc prolongation was also associated with sex (p < 0.0001) but not age (p = 0.486) or smoking (p = 0.1018). Females were more susceptible to QT prolongation than males.” | Observational study, Population restricted to Inner Mongolia, relatively small sample size, analysis for some confounding factors, such as medication use, not performed |

| Chen, C.-J., Chiou, H.-Y., Chiang, M.-H., Lin, L.-J., and Tai, T.-Y. from ref. [110] | Cohort | Residents in 60 villages of the area of Taiwan with Endemic Arseniasis (1,355,915 person-years) | “Based on 1 355 915 person-years and 217 ischemic heart disease (IHD) deaths, the cumulative IHD mortalities from birth to age 79 years were 3.4%, 3.5%, 4.7%, and 6.6%, respectively, for residents who lived in villages in which the median arsenic concentrations in drinking water were <0.1, 0.1 to 0.34, 0.35 to 0.59, and greater or equal to 0.6 mg/L. A cohort of 263 patients affected with blackfoot disease (BFD), a unique arsenic-related peripheral vascular disease, and 2293 non-BFD residents in the endemic area of arseniasis were recruited and followed up for an average period of 5.0 years. There was a monotonous biological gradient relationship between cumulative arsenic exposure through drinking artesian well water and IHD mortality. The relative risks were 2.5, 4.0, and 6.5, respectively, for those who had a cumulative arsenic exposure of 0.1 to 9.9, 10.0 to 19.9, and greater or equal to 20.0 mg/L-years compared with those without the arsenic exposure after adjustment for age, sex, cigarette smoking, body mass index, serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and disease status for hypertension and diabetes through proportional-hazards regression analysis. BFD patients were found to have a significantly higher ISHD mortality than non-BFD residents, showing a multivariate-adjusted relative risk of 2.5 (95% CI, 1.1 to 5.4).” | Obserational Study, Restricted to Taiwanese populations in area with endemic high exposure (e.g., areas with “blackfoot disease”) |

| Zheng, L. Y., Umans, J. G., Yeh, F., Francesconi, K. A., Goessler, W., Silbergeld, E. K., Bandeen-Roche, K., Guallar, E., Howard, B. V., Weaver, V. M., and Navas-Aciena, A. from ref. [114] | American Indian adults age 45–74 in the Strong Heart Study (3851 in cross sectional analysis, 3119 in rospective analysis) | “The adjusted odds ratio (OR; 95% confidence interval) of prevalent CKD for an interquartile range in total arsenic was 0.7 (0.6, 0.8), mostly due to an inverse association with inorganic arsenic (OR 0.4 [0.3, 0.4]). Monomethylarsonate and dimethylarsinate were positively associated with prevalent CKD after adjustment for inorganic arsenic (OR 3.8 and 1.8). The adjusted hazard ratio of incident CKD for an IQR in sum of inorganic and methylated arsenic was 1.2 (1.03, 1.41). The corresponding HRs for inorganic arsenic, monomethylarsonate, and dimethylarsinate were 1.0 (0.9, 1.2), 1.2 (1.00, 1.3), and 1.2 (1.0, 1.4).” | Observational study, Population restricted to mostly rural American Indians, eGFR limited to 3 measurements during study, population has high prevalence of comorbidities (including CKD, obesity, and diabetes) | |

| Mercury | ||||

| Study/Authors/Year | Study Type | Study population | Findings | Limitations |

| Hu, X. F., Lowe, M., and Chan, H. M. from ref. [120] | Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review | 14 studies with more than 34,000 participants in 17 countries | “Hg exposure was associated with an increase in nonfatal ischemic heart disease (relative risk (RR): 1.21 (0.98, 1.50)), all-cause mortality (RR: 1.21 (0.90, 1.62)), CVD mortality (RR: 1.68 (1.15, 2.45)), and mortality due to other heart diseases (RR: 1.50 (1.07, 2.11)). No association was observed between Hg exposure and stroke. A heterogeneous relationship was found between studies reporting fatal and nonfatal outcomes and between cohort and non-cohort studies. A J-shaped relationship between Hg exposure and different fatal/nonfatal outcomes was observed, with turning points at hair Hg concentrations of 1 μg/g for IHD and 2 μg/g for stroke and all CVD.” | Study populations mainly Caucasian, combined cohort and non-cohort studies when comparing nonfatal CVD events, did not include protective effects of certain nutrients (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids) that were part of the analysis in some studies |

| Downer, M. K., Martínez-González, M. A., Gea, A., Stampfer, M., Warnberg, J., Ruiz-Canela, M., Salas-Salvadó, J., Corella, D., Ros, E., Fitó, M., Estruch, R., Arós, F., Fiol, M., Lapetra, J., Serra-Majem, L., Bullo, M., Sorli, J. V., Muñoz, M. A., García-Rodriguez, A., … Gómez-Gracia, E. from ref. [121] | Nested Case-Control | 7477 participants in the PREDIMED trial at high risk for CVD at baseline | “Mean (±SD) toenail mercury concentrations (μg per gram) did not significantly differ between cases (0.63 (±0.53)) and controls (0.67 (±0.49)). Mercury concentration was not associated with cardiovascular disease in any analysis, and neither was fish consumption or n-3 fatty acids. The fully-adjusted relative risks for the highest versus lowest quartile of mercury concentration were 0.71 (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 0.34, 1.14; p = 0.37) for the nested case-control study, 0.74 (95% CI, 0.32, 1.76; p = 0.43) within the Mediterranean diet intervention group, and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.13, 1.96; p = 0.41) within the control arm of the trial.” | Observational study, only used one measure of toenail mercury, possible negative confounding by association of omega-3 fatty acid with fish take, population restricted to adults enrolled in PREDIMED trial in Spain |

| Mozaffarian, D., Shi, P., Morris, J. S., Spiegelman, D., Grandjean, P., Siscovick, D. S., Willett, W. C., and Rimm, E. B. from ref. [122] | Prospective cohort | 3427 participants with matched risk-set-sample controls according to age, sex, race, and smoking status | “0.23 μg per gram (interdecile range, 0.06 to 0.94) in the case participants and 0.25 μg per gram (interdecile range, 0.07 to 0.97) in the controls. In multivariate analyses, participants with higher mercury exposures did not have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. For comparisons of the fifth quintile of mercury exposure with the first quintile, the relative risks were as follows: coronary heart disease, 0.85 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69 to 1.04; p = 0.10 for trend); stroke, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.62 to 1.14; p = 0.27 for trend); and total cardiovascular disease, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.72 to 1.01; p = 0.06 for trend). Findings were similar in analyses of participants with low selenium concentrations or low overall fish consumption and in several additional sensitivity analyses.” | Observational Study, population restricted to United states, only used one measure of toenail mercury, possible negative confounding by association of omega-3 fatty acid with fish take |