Treating Depression in Dementia Patients: A Risk or Remedy—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

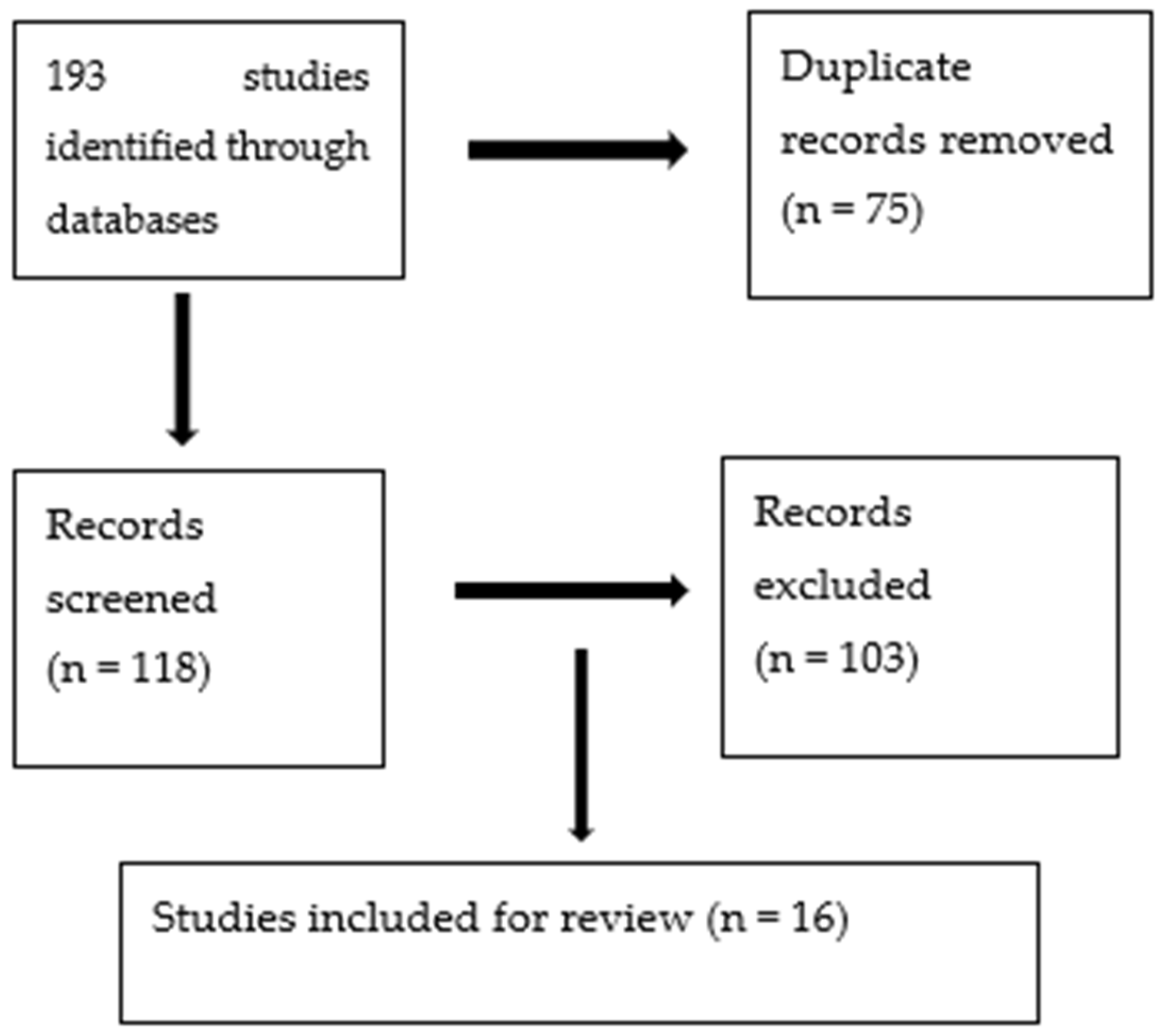

2. Method

2.1. Type of Review

2.2. Studies Considered for This Review

3. Results

3.1. Evidence of Antidepressant Effectiveness in Dementia Patients with Depression through Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

| First Author/Year | Type of Participants | Treatment | Duration | Outcome Measure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petracca et al., 1996 [25] | NINCDS-ADRDA for probable AD; mean MMSE = 21.5; Hachinski ischemic score < 4; DSM-III-R MDD; HAM-D > 10. | Clomipramine 25 mg to 100 mg, n = 11; placebo, n = 10 | 6 weeks. | HDRS, MMSE, FIM score. | Significant improvement in depression scores in clomipramine group, no difference in MMSE scores. |

| Roth et al., 1996 [24] | DSM-III for dementia and depression; mean MMSE = 20.2; GDS ≥ 5; HAM-D > 14. | Moclobemide 400 mg/day or placebo, N = 694 | 6 weeks. | HDRS, MMSE. | Moclobemide was superior to the placebo in improving depression score (p = 0.001). |

| Petracca et al., 2001 [21] | NINCDS-ADRDA for probable dementia and DSM-IV for MDD and minor depression; HAM-D >14; Hachinski ischemic score < 4; mean MMSE = 23.2. | Fluoxetine 10–40 mg, n = 20; placebo, N = 21. | 6 weeks. | HDRS, MMSE, FIM score. | The fluoxetine group did not differ significantly from the placebo group. |

| Lyketsos et al., 2003 (DIAD) [26] | NINCDS-ADRDA for probable AD; DSM-IV for major depressive episode; mean MMSE = 16.9. | Sertraline 95 mg/day, N = 24; placebo, n = 20. | 12 weeks. | CSDD, HDRS. | Sertraline significantly improves CSDD score (p = 0.02) and HDRS score (p = 0.01), compared to placebo. |

| de Vasconcelos et al., 2007 [22] | DSM-IV for probable dementia and MDD; MMSE = 10–24. | Venlafaxine 75 mg/day, n = 11; placebo, n = 12. | 6 weeks. | MADRS CGI. | No significant effect in MADRS CGI scores in venlafaxine group compared to placebo. |

| Rosenberg et al., 2010 [23] | DSM-IV for AD; mean MMSE = 20; Olin’s provisional diagnostic criteria for depression. | Sertraline 25–125 mg/day, n = 67; placebo, n = 64. | 12 weeks. | CSDD. | No significant difference in CSDD scores between groups; sertraline group reported more adverse events. |

| Weintraub et al., 2010 [28] | DSM-IV dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease; mean MMSE = 20; Olin’s provisional diagnostic criteria for depression. | Sertraline 25–125 mg per day, n = 67; placebo, n = 64. | 24 weeks. | CSDD. | No significant difference in improvement in CSDD score between groups. |

| Drye L.T. et al., 2011 DIAD-2 [29] | NINCDS-ADRDA for probable AD (MMSE = 10–26). | Sertraline (100 mg/day) vs. placebo, n = 131. | 24 weeks. | mADCS-CGIC; CSDD. | No significant difference between CSDD and mADCS-CGIC scores between groups; significantly more side effects in the treatment group. |

| Banerjee S, et al., 2011 [30] and 2013 [31] (HTA-SADD) [32] | NINCDS-ADRDA for probable AD; mean MMSE = 18.1; Olin’s criteria for depression in AD l; CSDD > 8. |

Sertraline 150 mg/day, n = 107; mirtazapine 45 mg/day, n = 108; placebo, n = 111. | 13 weeks, 39 weeks. | CSDD. | Differences in CSDD scores at 13 weeks from an adjusted linear mixed model: mean difference (95% CI) placebo–sertraline 1.17 (−0.23 to 2.78; p = 0.102); placebo–mirtazapine 0.01 (−1.37 to 1.38; p = 0.991); and mirtazapine–sertraline 1.16 (−0.27 to 2.60; p = 0.112). Placebo group had fewer side effects than treatment group. |

| Romeo R. et al., 2013 [40] | Dementia: probable or possible AD; BPSD: depression lasting ≥4 weeks; CSDD > 8. | Sertraline 150 mg/day, n = 107; mirtazapine 45 mg/day, n = 108; placebo, n = 111. | 13 weeks, 39 weeks. | CSDD. | Mirtazapine and sertraline were not cost-effective for treating depression in dementia (p > 0.05). |

| An H. et al., 2017 [33] | Dementia: probable or possible AD; MMSE score = 10–26; depression defined by Olin’s provisional diagnostic criteria; GDS > 5. |

Escitalopram 15 mg/day, n = 27; placebo, n = 33. | 12 weeks. | CSDD. | No significant change in CSDD scores between the two groups (p = 0.76); no difference in adverse effect between groups (p = 0.83). |

| Zuidersma M. et al., 2019 [27] | Dementia: probable or possible AD; BPSD: depression lasting ≥4 weeks; CSDD > 8. |

Sertraline 150 mg/day, n = 107; mirtazapine 45 mg/day, n = 108; placebo, n = 111. | 13 weeks, 39 weeks. | LCA of CSDD yielded the following four subgroups: 1. Severe; 2. Psychological; 3. Affective; 4. Somatic. | Symptom-based subgroup analysis revealed that mirtazapine was more effective in the psychological symptoms subgroup at 13 weeks (adjusted estimate: −2.77 [standard error (SE) 1.16; 95% confidence interval: −5.09 to −0.46]), which remained, but lost statistical significance at week 39 (adjusted estimate −2.97 [SE 1.59; 95% confidence interval: −6.15 to 0.20]). |

| Takemoto et al., 2020 [41] | Dementia: probable or possible AD; GDS > 5. |

Sertraline 31.8 mg, n = 11; placebo, N = 11; escitalopram 7.3 mg, N = 13; placebo, n = 11. | 12 weeks. | GDS. | Sertraline was not better than the placebo, but the escitalopram group showed a significant improvement in GDS score from the baseline (8.2 ± 3.5) to 3 M (5.7 ± 2.6, p = 0.04). |

| Banerjee S et al., 2021 (SYMBAD) [34] | Dementia: probable or possible AD; CMAI score of >45. | Mirtazapine 45 mg/day, n = 102; placebo, n = 102. | 12 weeks. | CMAI. | No benefit of mirtazapine compared with placebo (adjusted mean difference −1.74, 95% CI −7.17 to 3.69; p = 0.53). Potentially higher mortality with use of mirtazapine (p = 0.065). |

| Jeong H.W. et al., 2022 [39] | AD diagnosis using NINCDS-ADRDA criteria; MMSE score = 10–26; depression defined by Olin’s provisional diagnostic criteria; GDS > 5. | Vortioxetine 20 mg/day, n = 49; placebo, n = 51. | 12 weeks. | CSDD, GDS. | No benefit of vortioxetine over placebo (p > 0.05). Adverse events similar in both groups (p > 0.05). |

3.2. Evidence of Antidepressant Effectiveness in Dementia Patients with Depression through Meta-Analysis

| First Author/Year | Studies Included | Intervention (Drug vs. Placebo) | Mean Duration | Outcome Measure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bains et al. (Cochrane review), 2002 [17] | Seven RCTs; only four were entered into meta-analysis; N = 137. | Imipramine (Reifler, 1989); clomipramine (Petracca, 1996); fluoxetine (Petracca, 2001); Sertraline (DIADS, 2003). | 6–12 weeks. | Change in HDRS and CSDD. | Inconclusive. Out of all studies, only Lyketsos et al. [26] showed significant improvement in depression with sertraline. Adverse effects were significantly less frequent in the placebo group. |

| Thompson et al., 2007 [44] | Five RCTs; N = 165. | Imipramine (Reifler, 1989); clomipramine (Petracca, 1996); sertraline (Magai, 2001); fluoxetine (Petracca, 2001); sertraline (DIADS, 2003). | 6–12 weeks. | Response (↓ ≥50%); remission HDRS ≤ 7. | AD was superior to placebo for both treatment response (odds ratio [OR] 2.32; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04 to 5.16) and remission of depression (OR 2.75; 95% CI, 1.13 to 6.65). There were no significant differences between the two groups for change in cognition (weighted mean difference −0.71, 95% CI, −3.20 to 1.79), overall dropouts (OR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.29 to 1.66), or dropout due to AEs (OR 1.41; 95% CI 0.36 to 5.54). |

| Nelson et al. (2011) [16] | Seven RCTs; N = 330. | Imipramine (Reifler, 1989); clomipramine (Petracca, 1996); sertraline (Magai, 2001); fluoxetine (Petracca, 2001); sertraline (DIADS, 2003); venlafaxine (de Vas, 2007); sertraline (DIADS-2, 2010). | 6–12 Weeks. | Response (↓ ≥50%); remission (HDRS ≤ 7, CSDD ≤ 6, MADRS ≤ 10). | AD was NOT superior to placebo for both treatment response (odds ratio OR = 2.12 (95% confidence interval (CI) 5 0.95–4.70) and remission of depression (OR 1.97 (95% CI 5 0.85–4.55). No increases in discontinuation rate and adverse event frequency were observed in the treatment group. |

| Sepehry et al., 2012 [42] | 12 RCTs, 5 included in meta-analysis; n = 598. | 12 weeks. | Change in HDRS and CSDD. | No significant effects of SSRIs in two depression nested analyses, including CSDD and HDRS (p > 0.05). | |

| Ortego et al., 2017 [43] | Seven RCTs; n = 311. | Sertraline and mirtazapine (Banerjee, 2011); three studies of sertraline (Lyketsos, 2003, Rosenberg, 2010, and Magai et al., 2000); clomipramine (Petracca, 1996); fluoxetine (Petracca, 2001); imipramine (Reifler, 1989). | 13 weeks, 39 weeks. | Change in HDRS, CSDD, and MADRS. | No significant drug/placebo differences for depressive symptoms (SMD −0.13; 95% CI −0.49 to 0.24). |

| Dudas et al. (Cochrane review), 2018 [45] | 10 RCTs; n = 15,928; eight studies entered into meta-analysis. | Escitalopram (An, 2017); sertraline and mirtazapine (Banerjee, 2011); venlafaxine (de Vasconcelos, 2007); sertraline (Rosenberg, 2010 and Weintraub, 2010); maprotiline (Fuchs, 1993); moclobemide (Roth, 1996); sertraline (Lyketsos, 2003); clomipramine (Petracca, 1996); fluoxetine (Petracca, 2001). | 13 weeks 39 weeks | Response (↓ ≥50% on HDRS, mADCS-CGI rating of 2 or <); remission (HDRS ≤ 7, CSDD ≤ 6, MADRS ≤ 10) | No difference in scores on depression symptom rating scales between the antidepressant and placebo treated groups at 6 to 13 weeks (SMD −0.10, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.26 to 0.06 No difference at 24 to 39 weeks (MD = 0.59, 95% CI −1.12 to 2.3); subgroup analyses of various types of AD did not indicate a difference in efficacy; treatment group was significantly more likely to experience AEs; no differences in measures of cognitive function or activities of daily living and quality of life between antidepressant and placebo groups were found; AEs occurred more in participants given antidepressants compared to those on placebos. |

| Zhang, J. et al., 2023 (HTA-SADD) [48] | 15 RCTs; one prospective cohort; n = 510. | Three studies of escitalopram; one study of citalopram; three studies of fluoxetine; one study of paroxetine; seven studies of sertraline. | 12 weeks. | Change in CSDD, HDRS, MADRS, and GDS. | Escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline significantly alleviated depressive symptoms in AD patients (0.813 SMD, 95% CI, 0.207 to 1.419, p = 0.009, 1.244 SMD, 95% CI, 0.939 to 1.548, p < 0.000, and 0.818 SMD, 95% CI, 0.274 to 1.362, p < 0.000). |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AChEIs | acetylcholinesterase inhibitors |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CMAI | Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory |

| CDR | Clinical Dementia Rating Scale |

| CSDD | Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia |

| DIAD | depression in Alzheimer’s disease |

| DSM-IVTR | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition, text revision) |

| GDS | Geriatric Depression Scale |

| HDRS | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HTA-SADD | health technology assessment study of the use of antidepressants for depression in dementia |

| mADCS-CGI | modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change |

| MAOIs | monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| NPI-M | Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Mood |

| NaSSA | noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant |

| NINCDS-ADRDA | National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association |

| PDRS | Psychogeriatric Depression Rating Scale—activities of daily living subscale |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| TCAs | tricyclic antidepressants |

| SMD | standardized mean difference |

| SYMBAD | study of mirtazapine for agitated behaviors in dementia trial |

References

- Asmer, M.S.; Kirkham, J.; Newton, H.; Ismail, Z.; Elbayoumi, H.; Leung, R.H.; Seitz, D.P. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of major depressive disorder among older adults with dementia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 79, 15460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, H.; Roiser, J.P.; Howard, R. Antidepressant medications in dementia: Evidence and potential mechanisms of treatment-resistance. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.J. Evidence-based pharmacological management and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry Resid. J. 2019, 14, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyhe, T.; Reynolds, C.F.; Melcher, T.; Linnemann, C.; Klöppel, S.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Dubois, B.; Lista, S.; Hampel, H. A common challenge in older adults: Classification, overlap, and therapy of depression and dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 13, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.L.; Raue, P.; Halpert, K.D.; Adams, S.; Titler, M.G. Detection of depression in older adults with dementia. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Noh, G.O.; Kim, K. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and family caregiver burden: A path analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, M.S.; Werner, P.; Davidson, M.; Noy, S. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 17, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelis, S.M.; Wu, Y.T.; Matthews, F.E.; Martyr, A.; Quinn, C.; Rippon, I.; Rusted, J.; Thom, J.M.; Kopelman, M.D.; Hindle, J.V.; et al. The impact of co-morbidity on the quality of life of people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL study. Age Aging 2019, 48, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olin, J.T.; Schneider, L.S.; Katz, I.R. Provisional Diagnostic Criteria for Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 10, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settle, E.C., Jr. Antidepressant drugs: Disturbing and dangerous adverse events. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59 (Suppl. S16), 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman, A.H.; Bigger, J.T., Jr. Cardiovascular effects of therapeutic doses of tricyclic antidepressants: A review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1981, 38, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srifuengfung, M.; Pennington, B.R.T.; Lenze, E.J. Optimizing treatment for older adults with depression. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 13, 20451253231212327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobieraj, D.M.; Martinez, B.K.; Hernandez, A.V.; Coleman, C.I.; Ross, J.S.; Berg, K.M.; Steffens, D.C.; Baker, W.L. Adverse Effects of Pharmacologic Treatments of Major Depression in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabins, P.V.; Blacker, D.; Rovner, B.W.; Rummans, T.; Schneider, L.S.; Tariot, P.N.; Blass, D.M.; McIntyre, J.S.; Charles, S.C.; Anzia, D.J.; et al. American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, second edition. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164 (Suppl. S12), 5–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.C.; Devanand, D.P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled antidepressant studies in people with depression and dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bains, J.; Birks, J.; Dening, T. Antidepressants for treating depression in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, 4, CD003944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, N.; McCleary, L.; Freiheit, E.; Molnar, F.; Dalziel, W.; Cohen, C.; Turner, D.; Miyagishima, R.; Silvius, J. Antidepressant and antipsychotic prescribing in primary care for people with dementia. Can. Fam. Physician 2018, 64, e488–e497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinez, C.; Jones, R.W.; Rietbrock, S. Trends in the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias including those treated with antidementia drugs in the community in the UK: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracca, G.M.; Chemerinski, E.; Starkstein, S.E. A double-blind, placebocontrolled study of fluoxetine in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. IPA 2001, 13, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vasconcelos Cunha, U.G.; Lopes Rocha, F.; Avila de Melo, R.; Alves Valle, E.; de Souza Neto, J.J.; Mendes Brega, R.; Magalhães Scoralick, F.; Araújo Silva, S.; Martins de Oliveira, F.; da Costa Júnior, A.L.; et al. A placebocontrolled double-blind randomized study of venlafaxine in the treatment of depression in dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007, 24, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, P.B.; Martin, B.K.; Frangakis, C.; Mintzer, J.E.; Weintraub, D.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Schneider, L.S.; Rabins, P.V.; Munro, C.A.; Meinert, C.L.; et al. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.; Mountjoy, C.Q.; Amrein, R. Moclobemide in elderly patients with cognitive decline and depression: An international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 1996, 168, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracca, G.; Tesón, A.; Chemerinski, E.; Leiguarda, R.; Starkstein, S.E. A doubleblind placebo-controlled study of clomipramine in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1996, 8, 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos, C.G.; Del Campo, L.; Steinberg, M.; Miles, Q.; Steele, C.D.; Munro, C.; Baker, A.S.; Sheppard, J.M.; Frangakis, C.; Brandt, J.; et al. Treating depression in alzheimer disease: Efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: The DIADS. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidersma, M.; Chua, K.C.; Hellier, J.; Voshaar, R.O.; Banerjee, S. HTA-SADD Investigator Group. Sertraline and Mirtazapine Versus Placebo in Subgroups of Depression in Dementia: Findings From the HTA-SADD Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weintraub, D.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Drye, L.T.; Martin, B.K.; Frangakis, C.; Mintzer, J.E.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Schneider, L.S.; Rabins, P.V.; Munro, C.A.; et al. DIADS-2 Research group. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in alzheimer disease: Week-24 outcomes. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drye, L.T.; Martin, B.K.; Frangakis, C.E.; Meinert, C.L.; Mintzer, J.E.; Munro, C.A.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Rabins, P.V.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Schneider, L.S.; et al. Do treatment effects vary among differing baseline depression criteria in depression in Alzheimer’s disease study ± 2 (DIADS-2)? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Hellier, J.; Dewey, M.; Romeo, R.; Ballard, C.; Baldwin, R.; Bentham, P.; Fox, C.; Holmes, C.; Katona, C.; et al. Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): A randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Hellier, J.; Romeo, R.; Dewey, M.; Knapp, M.; Ballard, C.; Baldwin, R.; Bentham, P.; Fox, C.; Holmes, C.; et al. Study of the use of antidepressants for depression in dementia: The HTA-SADD trial—A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and costeffectiveness of sertraline and mirtazapine. Health Technol. Assess. Winch. Engl. 2013, 17, 1–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, S.; McKay, R.; Looi, J. Limited antidepressant efficacy in the context of limited evidence. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2012, 46, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, H.; Choi, B.; Park, K.W.; Kim, D.H.; Yang, D.W.; Hong, C.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, S.H. The effect of escitalopram on mood and cognition in depressive Alzheimer’s disease subjects. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 2, 727–735. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; High, J.; Stirling, S.; Shepstone, L.; Swart, A.M.; Telling, T.; Henderson, C.; Ballard, C.; Bentham, P.; Burns, A.; et al. Study of mirtazapine for agitated behaviours in dementia (SYMBAD): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iovieno, N.; Papakostas, G.I.; Feeney, A.; Fava, M.; Mathew, S.J.; Iosifescu, D.I.; Murrough, J.W.; Macaluso, M.; Hock, R.S.; Jha, M.K. Vortioxetine versus placebo for major depressive disorder: A comprehensive analysis of the clinical trial dataset. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 34253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, M.M.; Fixen, D.R.; Linnebur, S.A.; Pearson, S.M. Cognitive effects of vortioxetine in older adults: A systematic review. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 11, 20451253211026796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumbo, E.; Cumbo, S.; Torregrossa, S.; Migliore, D. Treatment effects of vortioxetine on cognitive functions in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients with depressive symptoms: A 12 month, open-label, observational study. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 6, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumbo, E.; Adair, M.; Åstrom, D.O.; Christensen, M.C. Effectiveness of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid Alzheimer’s disease in routine clinical practice: An analysis of a post-marketing surveillance study in South Korea. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 14, 1037816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.W.; Yoon, K.H.; Lee, C.H.; Moon, Y.S.; Kim, D.H. Vortioxetine Treatment for Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2022, 20, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, R.; Knapp, M.; Hellier, J.; Dewey, M.; Ballard, C.; Baldwin, R.; Bentham, P.; Burns, A.; Fox, C.; Holmes, C.; et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses for mirtazapine and sertraline in dementia: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ Psychiatry 2013, 202, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, M.; Ohta, Y.; Hishikawa, N.; Yamashita, T.; Nomura, E.; Tsunoda, K.; Sasaki, R.; Tadokoro, K.; Matsumoto, N.; Omote, Y.; et al. The Efficacy of Sertraline, Escitalopram, and Nicergoline in the Treatment of Depression and Apathy in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Okayama Depression and Apathy Project (ODAP). J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 76, 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepehry, A.A.; Lee, P.E.; Hsiung, G.Y.; Beattie, B.L.; Jacova, C. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease with comorbid depression: A meta-analysis of depression and cognitive outcomes. Drugs Aging 2012, 29, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgeta, V.; Tabet, N.; Nilforooshan, R.; Howard, R. Efficacy of Antidepressants for depression in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 58, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; Herrmann, N.; Rapoport, M.J.; Lanctôt, K.L. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants for treatment of depression in Alzheimer’s disease: A metaanalysis. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2007, 52, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudas, R.; Malouf, R.; McCleery, J.; Dening, T. Antidepressants for treating depression in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD003944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, A.; Lawlor, B.; Craig, S. Rating Scales in Old Age Psychiatry. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magai, C.; Kennedy, G.; Cohen, C.I.; Gomberg, D.A. A controlled clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of depression in nursing home patients with late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2000, 8, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, Z. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy outcomes of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression in Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2023, 23, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyth, A.L.; Gottfries, C.G. The clinical efficacy of citalopram in treatment of emotional disturbances in dementia disorders. A Nordic multicentre study. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 1990, 157, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taragano, F.E.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Mangone, C.A.; Allegri, R.F.; Comesaña-Diaz, E. A double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose trial of fluoxetine vs. amitriptyline in the treatment of major depression complicating Alzheimer’s disease. Psychosomatics 1997, 38, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katona, C.L.E.; Hunter, B.N.; Bray, J. A double-blind comparison of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine and imipramine in the treatment of depression with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1998, 13, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.; Spiro, J.R.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Lee, H.B.; Rosenblatt, A.; Lyketsos, C.G. An open-label study of escitalopram (Lexapro) for the treatment of ‘Depression of Alzheimer’s disease’ (dAD). Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowla, A.; Mosavinasab, M.; Haghshenas, H.; Haghighi, A.B. Does serotonin augmentation have any effect on cognition and activities of daily living in Alzheimer’s dementia?: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, R.; Manera, V.; Fabre, R.; Pradier, C.; Robert, P.; Tifratene, K. Evolution of the antidepressant prescribing in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders between 2010 and 2014: Results from the French National Database on Alzheimer’s Disease (BNA). J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 53, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhber, N.; Abdollahian, E.; Soltanifar, A.; Samadi, R.; Saghebi, A.; Haghighi, M.B.; Azarpazhooh, A. Comparison of sertraline, venlafaxine and desipramine eIects on depression, cognition and the daily living activities in alzheimer patients. Pharmacopsychiatry 2014, 47, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Johnell, K.; Jonasdottir Bergman, G.; Fastbom, J.; Danielsson, B.; Borg, N.; Salmi, P. Psychotropic drugs and the risk of fall injuries, hospitalisations and mortality among older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laitinen, M.L.; Lönnroos, E.; Bell, J.S.; Lavikainen, P.; Sulkava, R.; Hartikainen, S. Use of antidepressants among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: A nationwide register-based study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puranen, A.; Taipale, H.; Koponen, M.; Tanskanen, A.; Tolppanen, A.M.; Tiihonen, J.; Hartikainen, S. Incidence of antidepressant use in community-dwelling persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease: 13-year follow-up. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, T.; Barbui, C.; Clark, N.; Fleischmann, A.; Poznyak, V.; van Ommeren, M.; Yasamy, M.T.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Birbeck, G.L.; Drummond, C.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: Summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzhiemer’s disease and other dementias, Second ed. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 148, 370–378. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers. London: The British Psychological Society & Gaskell The Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2018. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng9 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Gauthier, S.; Patterson, C.; Chertkow, H.; Gordon, M.; Herrmann, N.; Rockwood, K.; Rosa-Neto, P.; Soucy, J.P. Recommendations of the 4th Canadian consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia (CCCDTD4). Can. Geriatr. J. 2012, 15, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguera-Ortiz, L.; Garcia-Ramos, R.; Grandas Perez, F.J.; López-Álvarez, J.; Montes Rodríguez, J.M.; Olazarán Rodríguez, F.J.; Olivera Pueyo, J.; Pelegrin Valero, C.; Porta-Etessam, J. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: A Delphi consensus on etiology, risk factors, and clinical management. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 638651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, A.L.; Yaffe, K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 7, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, V.; Federico, G.; Mele, G.; Garramone, F.; Esposito, M.; Aiello, M.; Salvatore, M.; Cavaliere, C. Brain Networks Involved in Depression in Patients with Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinson’s Disease: An Exploratory Resting-State Functional Connectivity MRI Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.; Fricker, A.D.; Devi, L.A.; Gomes, I. Mechanisms of action of antidepressants: From neurotransmitter systems to signaling pathways. Cell Signal. 2005, 17, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, N.; Morrell, L.; Banerjee, S. What is the therapeutic value of antidepressants in dementia? A narrative review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuka, S. Depression and Dementia in Older Adults: A Neuropsychological Review. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, N. Locus Coeruleus Malfunction Is Linked to Psychopathology in Prodromal Dementia With Lewy Bodies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 641101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubenko, G.; Moossy, J.; Kopp, U. Neurochemical correlates of major depression in primary dementia. Arch. Neurol. 1990, 47, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Outcome | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Nyth et al., 1990 [49] | Citalopram showed a significant improvement in emotional bluntness, anxiety, and depressed mood. | Combined double-blind and open techniques; looked at the effect of citalopram on emotional disturbance in patients with various subtypes of dementia; patients were not diagnosed with depression according to any recognized criteria. |

| Tarango et al., 1997 [50] | Fluoxetine and amitriptyline were equally effective but fluoxetine was better tolerated. | Randomized trial of amitriptyline vs. fluoxetine, for patients with probable AD and major depressive disorder, but it was not placebo-controlled. |

| Katona et al., 1998 [51] | Paroxetine and imipramine were both effective in the treatment of dAD. | Not a placebo-controlled trial; imipramine was compared with paroxetine in cognitively impaired and depressed patients. |

| Lyketsos et al., 2003 [25] | Sertraline was superior to the placebo. | Recruitment of patients from specialty clinic; strict criteria applied for diagnosis of dementia and MDD, so these findings may not apply for mild mood disturbances and other types of dementias. |

| Rao et al., 2006 [52] | Escitalopram was efficacious and safe for the treatment of dAD. | Open labelled study design; small size; no blinding or allocation concealment. |

| Mowla et al., 2007 [53] | Concomitant use of SSRI and Ach-I reported improved global functioning. | The patients were not diagnosed with depression; outcome was improvement in daily activity. |

| Mokhber et al., 2014 [54] | Sertraline better for treating depression than venlafaxine and desipramine. | No placebo group; small size; use of HDRS. |

| Takemoto et al., 2020 [41] | Serotonin had better efficacy than escitalopram. | Randomized single-blind prospective observational study; no placebo; small study; used GDS to measure depression. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sultan, S. Treating Depression in Dementia Patients: A Risk or Remedy—A Narrative Review. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9030064

Sultan S. Treating Depression in Dementia Patients: A Risk or Remedy—A Narrative Review. Geriatrics. 2024; 9(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9030064

Chicago/Turabian StyleSultan, Sadia. 2024. "Treating Depression in Dementia Patients: A Risk or Remedy—A Narrative Review" Geriatrics 9, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9030064

APA StyleSultan, S. (2024). Treating Depression in Dementia Patients: A Risk or Remedy—A Narrative Review. Geriatrics, 9(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9030064