1. Introduction

The desire to live in a familiar place is a universal aspiration [

1,

2]. This is also the central concept of living in a community, and the idea of “ageing in place” [

3,

4]. Residing in a familiar community helps maintain and enhance a person’s independence, dignity, and quality of life [

5]. However, this ability is influenced by several factors, such as disasters and disease. Despite the significance of this aspiration, adequate measures to address it are not often implemented during emergencies. Determining whether appropriate measures can be implemented under such circumstances, for the realisation of ageing in place, is an important public health issue.

Achieving ageing in a place during a disaster can be a challenging situation, due to various factors [

6,

7]. One such factor is the tendency of younger generations to establish new lives in evacuation destinations, whereas older generations prefer to remain in places where they have lived for many years [

8,

9]. This creates concerns about the emotional distress experienced by residents when they must relocate and adapt to new environments, leading to lifestyle changes [

10]. Furthermore, post-disaster areas often face rapid population decline and ageing [

11,

12], which has garnered national and international attention regarding the preservation of residents’ quality of life [

13]. Although countermeasures are crucial in disaster situations, the implementation of strategies to support ageing in place remains insufficient.

On 11 March 2011, a catastrophic event occurred, when the Great East Japan Earthquake struck with a magnitude of 9.0. Within an hour, a devastating tsunami occurred. Owing to these events, Units 1, 3, and 4 of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP), operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company, lost power. The loss of power rendered the reactors unable to cool, leading to explosions caused by the hydrogen generated at high temperatures [

14]. Consequently, radioactive material was released and dispersed outside the power plant, in the northwest direction. In response, the Japanese government declared a nuclear emergency, and issued an evacuation order for residents within 30 km of the reactor. Residents were promptly evacuated following the order. Subsequently, the evacuation order was gradually and partially lifted over time. However, many residents were unable to return to their original homes [

15]. Some of them decided to reside in the places where they had sought refuge during the evacuation.

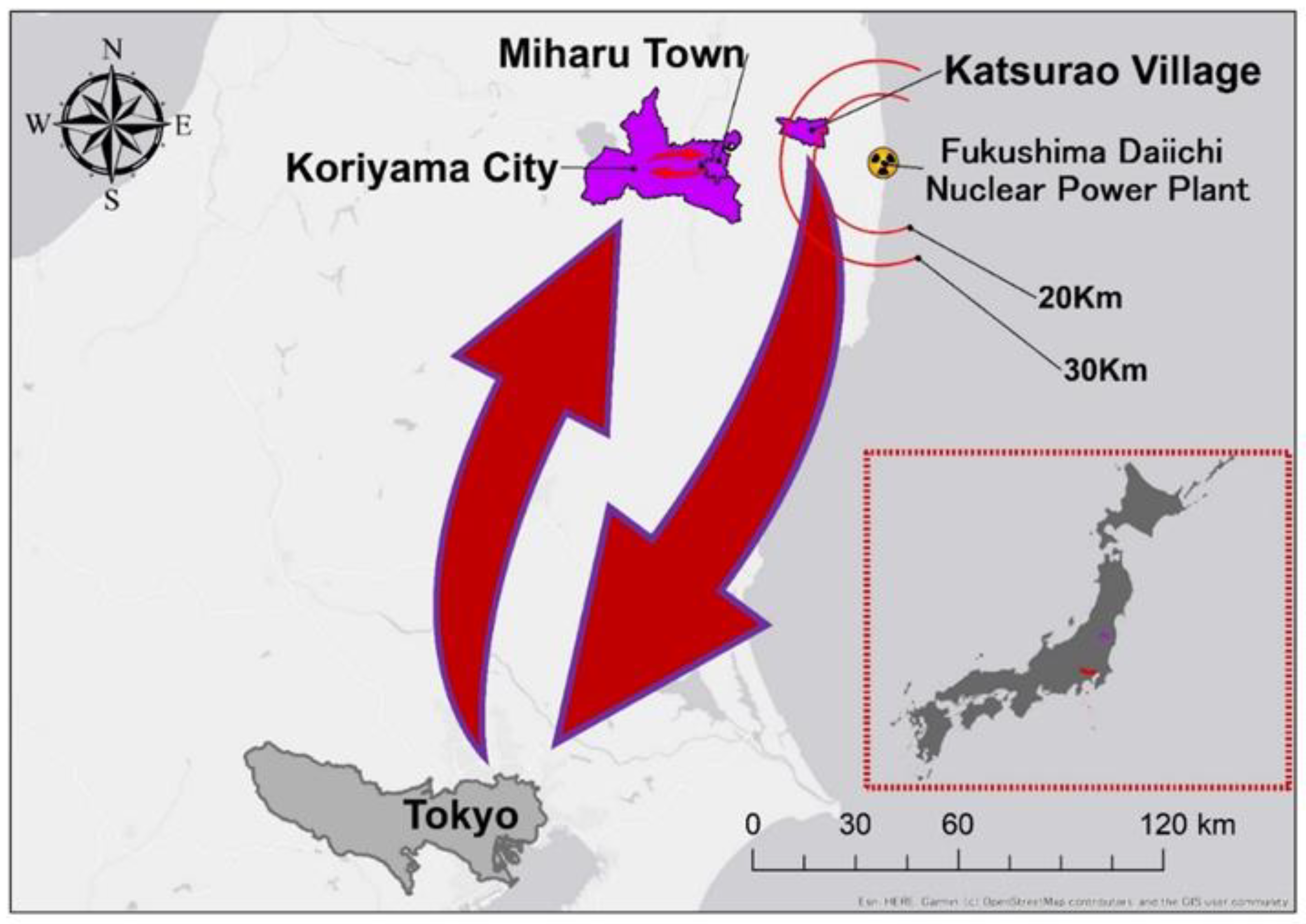

Katsurao Village, located approximately 20–30 km from the FDNPP, is a mountainous village with a population of approximately 1400. When the disaster struck, most residents evacuated to Miharu Town and Koriyama City. In the same year, temporary housing complexes were constructed in Miharu Town (

Figure 1). People living away from their home village began to show various secondary health effects [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Meanwhile, the evacuation order for Katsurao Village was lifted on a large scale in June 2016, and the residents have gradually been returning home. Presently, the number of returnees in the village is 324 (an ageing rate of 57%), representing 25.2% of the village’s registered population (1298 as of 1 May 2023). As many residents continue to stay at the evacuation site [

20,

21], an understanding of the situation of these evacuated residents is crucial to Japan’s return policy [

22,

23]. Since the lifting of the evacuation order in 2016, the village has implemented various measures to assist residents in rebuilding their lives [

24]. Nevertheless, many individuals maintain a multisite lifestyle, which includes their original house in the village, and a new house at an evacuation site.

The multisite lifestyle (living) in this report refers to a lifestyle involving living at multiple sites following a nuclear incident. Few studies have described situations in which large numbers of residents feel compelled to maintain their residences in multiple locations, amidst the ongoing return policies [

25]. Why do so many people maintain multiple sites of residence after a nuclear accident? The aim of this report is to provide insights into the present situation, and challenges associated with the multisite lifestyle experienced by residents after a nuclear incident. This is to gain a better understanding of the current conditions and difficulties they encounter and, subsequently, utilise these findings to support promotion of the health of residents experiencing evacuation.

2. Methodology and Data Collection

This case report was based on interviews, following observations and the selection of residents, to capture real-life social phenomena, and enhance the internal validity of the study [

26].

To clarify our research questions, we believe that conducting interviews is the best approach to bring forth the real voice of the residents. Although a questionnaire can also be useful, it cannot bring out the actual thoughts of the residents. Therefore, we carried out interviews with individual residents who were executing multisite living. The interviewees were selected via the following procedure.

The first author was engaged in cooperation with Katsurao Village as a public health nurse, to undertake health check-ups and home visits to acquire the health information of residents. Indeed, the first author participated in regional healthcare meetings once a month, to share health information, and discuss how to provide public health support. The first author studied the living situation of individual residents through observations, including daily conversations related to health maintenance at health check-up sites and home visits, and information shared at the meeting. As a result, the first author noticed and recognised the multisite living practised by Katsurao residents. Based on the research questions, the first author started interviewing residents who continued multisite living (20 of a total 200 residents). Among the 20 individuals whom we interviewed, we identified a woman representing a typical case of an older person living in multiple locations after the nuclear incident.

The interview was held face-to-face at the resident’s home, over three sessions in two months. The interview questions were as follows:

- (i)

How did you evacuate after the nuclear accident and up to the present?

- (ii)

How has your life changed with the evacuation and relocation?

- (iii)

The evacuation order has been lifted, but why don’t you return to Katsurao Village?

- (iv)

What are the good things and problems of living in multiple locations?

- (v)

Do you have any health concerns?

- (vi)

Are you satisfied with your current lifestyle?

We analysed the interview responses, and the results are summarised in the case presentation section.

Egenokoshi Housing Complex in Miharu Town (

Figure 1) is a public reconstruction housing for residents of Katsurao Village who were evacuated after the nuclear incident. The move-in began in April 2016. Seventy houses in the complex are occupied by 135 residents, and thirty-six houses are vacant. Among the 135 residents, 57 are aged 65 years and older (ageing rate: 42.2%). There are 22 elderly people living alone (22 houses), and 10 houses where only older people live (data as of 1 June 2022).

A staff member of the Katsurao Village office is stationed in a unit of the complex, and visits all the houses every day.

3. Case Presentation

A woman in her 90s lived in Katsurao Village with her husband before the incident in 2011. After the nuclear plant incident, her son, who resided in Tokyo, rushed to pick them up immediately. They evacuated from their village to a distant location, they then resided as evacuees in municipal housing in Tokyo for the following 8 years (

Figure 2). Because all three of their children lived in Tokyo, it was convenient for the couple to live there and receive support from their children. They made up their mind not to return to their village, because she and her husband were afraid of radiation exposure, derived from radioactive materials which scattered from the Fukushima nuclear power plant and covered their village. Their participation in anti-nuclear action provided the inspiration for the notion stated above.

After 8 years had passed in Tokyo since their evacuation, they purchased a new house in Koriyama City, and moved there (

Figure 2). Their reason for the purchase was to live close to the graves of their ancestors, which are located in their village where her former home had already been deconstructed. Two years after the movement, her husband died from illness, and she became alone. Although she was able to live physically independently, she felt alone because there were no communities she belonged to at the new location, as they were different from those in her original village. Concerned about her wellbeing, her children let her move to a residence in a public reconstruction housing for Katsurao Village residents located in Miharu Town—the Egenokoshi Housing Complex (

Figure 2). Fortunately, there was a vacant unit next to her sister’s residence in the complex, allowing her to move immediately. Consequently, she was able to build a relationship with the neighbours, including her sister. These relationships form the base of the local community network.

Currently, she lives in two locations, mainly in Miharu Town, while maintaining her home in Koriyama City. The reconstruction public housing where she moved was built to provide housing for Katsurao residents after the evacuation order was lifted. Her daughter who lived in Tokyo came to Fukushima prefecture to take care of her. During her 10-day stay, they travelled back and forth between Koriyama and Miharu. After her daughter left, the elderly woman continued living in Miharu. On her life there, she says, “I feel at ease here because there are people from the village”; “I feel reassured that people check on me every day”; and “Rental fee is cheap, less than JPY 10,000 (app. USD 70), good for a pensioner”. Recently, she was certified as a person requiring long-term care, and she attends daycare once a week. She talks about her life in Miharu Town as follows: “It is good for me that the daycare service car picks me up”; “I can still do things around me”; and “I want to live here for the rest of my life”.

Judging from her comments about her life in Miharu Town, she appears satisfied with her living circumstances and lifestyle; in particular, she feels comfortable with her relationship with her neighbours. Indeed, she accepts moving between two locations. As she wants to live in Miharu Town, she will not return to her original village.

4. Discussion

Text analysis was performed on the interview that we conducted. Text analysis includes not only the text itself, but also the context related to the situations the participant had faced, and her background.

This case is typical of nuclear disasters, where multiple sites continue to be maintained, including evacuation centres and places of origin. Nuclear disasters differ significantly from others, such as tsunamis and typhoons; they involve concerns about radioactive contamination, which leads evacuees to leave their original residence for a long period [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The evacuation order described here lasted longer than the evacuees’ expectation. Therefore, evacuees searched for houses at the evacuation sites, as compensation for nuclear disaster evacuees and housing subsidies were paid [

31]. Indeed, as they thought that they would never be able to go back to their original land, many residents continued to live at their evacuation site even after the evacuation order had been lifted [

32]. In another aspect, the special law for nuclear disaster evacuees helped to establish life at evacuation sites [

33]. However, many of the evacuees still miss their original land, which has the same landscape as before. Therefore, they commute back to their original homes for work, maintain them, and restart their customs at their original site. That is why evacuees still carry out multisite living, 12 years after the nuclear incident occurred.

In addition to the description above, the following multiple challenges faced by an elderly woman resulted in multisite living: firstly, she was forced to relocate during her old age due to the nuclear incident. Secondly, her husband passed away, which led to her living alone. Leaving a familiar place of residence in old age, and the death of a companion, often lead to social isolation [

34]. In other words, it is difficult for elderly people to build a community relationship after relocation. Indeed, it is possible that older people may migrate to seek social resources, such as medical, nursing, and preventive care, in line with the health problems they face. As a result of seeking a place to improve their quality of life, they opt to maintain multiple bases, such as the original place, the evacuation site, and the nursing home [

25].

Over the course of repeated displacement, the follow-up and social support for residents’ health problems can be lacking [

35,

36]. In this case, however, public housing for disaster victims has made it possible for the elderly to build new relationships with familiar people, and to live close to the affected areas [

37,

38,

39]. Intangible support, such as life support staff calls, informal support among residents, and shuttle buses to and from hospitals have been very helpful. Therefore, it is possible to bring about a happy and independent life, even if it is not in one’s original home [

40].

This study has some limitations. The case report described here is only one of the 20 cases in Katsurao Village that we have encountered, and it is limited to the older population. To address these limitations, we believe that the study should be expanded to include surrounding areas and different age groups.

5. Conclusions

Our findings, through an interview, are the results of the forced relocation of victims after the nuclear incident, subsequent recovery, and local measures under the national return policy. The immediate challenges, including the health problems seen among the survivors, led residents to live in multiple locations, and the post-disaster social security policy made this possible. Reconstruction housing complexes led older people to settle, and allowed them to develop relationships with neighbours from the same village, which helped them to restart their lives in a familiar community after the disaster. This is applicable not only to disaster preparedness, but also in normal settings with rapid ageing.

Regarding the difficulties encountered, this region is advanced because of the population’s rapid aging and decline. We think that the findings of our research can provide a number of recommendations for global concerns with a similar regional component.

Author Contributions

N.I., I.A., P.S. and S.M. conducted field surveys; N.I., I.A., P.S., S.M. and M.S. drafted the manuscript; N.M., H.S., T.A., A.F., M.S., T.Z. and C.Y. revised the manuscript; and N.I. and M.T. supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant number MO22K11233) and Research Project on the Health Effects of Radiation organised by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Fukushima Medical University Ethics Committee (Approval #2022-054; date: 20 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the residents and officials of Katsurao Village for their cooperation in conducting this study. We also thank the research assistant Rika Ishizuka (Office for Diversity and Inclusion at Fukushima Medical University) for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ivry, J. Aging in place: The role of geriatric social work. Fam. Soc. 1995, 76, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelen, J.; Griffiths, K.A. Housing for the aged: New roles for social work. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1983, 16, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynoos, J. Public policy and aging in place: Identifying the problems and potential solutions. In Aging in Place: Supporting the Frail Elderly in Residential Environments; Scott Foresman & Company: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 167–208. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, J.T. Living independently with neighbors who care: Strategies to facilitate aging in place. In Aging in Place: Supporting the Frail Elderly in Residential Environments; Scott Foresman & Company: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tilson, D. Aging in Place: Supporting the Frail Elderly in Residential Environments; Scott Foresman & Company: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Löfqvist, C.; Granbom, M.; Himmelsbach, I.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F.; Haak, M. Voices on Relocation and Aging in Place in Very Old Age—A Complex and Ambivalent Matter. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, R.A.; Acosta, J.D.; Chen, E.K.; Carbone, E.G.; Xenakis, L.; Adamson, D.M.; Chandra, A. Improving Disaster Resilience Among Older Adults: Insights from Public Health Departments and Aging-in-Place Efforts. Rand Health Q. 2018, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Kinoshita, Y.; Morita, T.; Tsubokura, M. Promoting independent living and preventing lonely death in an older adult: Soma Idobata-Nagaya after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e243117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, N.; Morita, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kobashi, Y.; Murakami, M.; Ozaki, A.; Nonaka, S.; Sawano, T.; Oikawa, T.; Tsubokura, M. Association of Living in Evacuation Areas with Long-Term Care Need after the Fukushima Accident. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 111–116.e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Tsubokura, M. Lower Psychological Distress Levels among Returnees Compared with Evacuees after the Fukushima Nuclear Accident. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2019, 247, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, T.; Leppold, C.; Tsubokura, M.; Nemoto, T.; Kanazawa, Y. The increase in long-term care public expenditure following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Nomura, S.; Furutani, T.; Leppold, C.; Tsubokura, M.; Ozaki, A.; Ochi, S.; Kami, M.; Kato, S.; Oikawa, T. Demographic transition and factors associated with remaining in place after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster and related evacuation orders. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, V.; Kaufman, S.R.; van Hattum, T.; Moody, S. Aging disaster: Mortality, vulnerability, and long-term recovery among Katrina survivors. Med. Anthropol. 2011, 30, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielen, H. The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Accident—An Overview. Health Phys. 2012, 103, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima_Revitalization_Station. Number of Evacuees. Available online: https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal/hinansya.html (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Tsubokura, M. Secondary health issues associated with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, based on the experiences of Soma and Minamisoma Cities. J. Natl. Inst. Public Health 2018, 67, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Nomura, S.; Tsubokura, M.; Leppold, C.; Gilmour, S.; Ochi, S.; Ozaki, A.; Shimada, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Inoue, M.; et al. Excess mortality due to indirect health effects of the 2011 triple disaster in Fukushima, Japan: A retrospective observational study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumura, S.; Goto, A.; Yamazaki, S.; Reich, M.J. Excess mortality among relocated institutionalized elderly after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Public Health 2013, 127, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Yasumura, S.; Satoh, H.; Suzuki, H.; Sakai, A.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Ozasa, K.; et al. Effect of Evacuation on Body Weight After the Great East Japan Earthquake. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KatsuraoVillage. Status of Return and Evacuation of Katsurao Village. Available online: https://www.katsurao.org/soshiki/2/kison.html (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Reconstruction Agency in Japan. Katsurao Village Resident Return Survey. Available online: https://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat1/sub-cat1-4/ikoucyousa/r3_houkokusyo_katsurao.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Kobashi, Y.; Nishikawa, Y.; Morita, T.; Omata, F.; Ito, N.; Tsubokura, M. Demographic Change of the Kawauchi Special Nursing Home Occupants in a Former Evacuation Area After the Nuclear Power Plant Accident: A Retrospective Observational Study. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 17, e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobashi, Y.; Morita, T.; Ozaki, A.; Sawano, T.; Moriyama, N.; Ito, N.; Tsubokura, M. Long-term Care Utilization Discrepancy Among the Elderly in Former Evacuation Areas, Fukushima. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 892–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Moriyama, N.; Ito, N.; Abe, T.; Morita, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Tsubokura, M. Long-term care issues in a municipality affected by the great East Japan earthquake: A case of Katsurao Village, Fukushima prefecture. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Moriyama, N.; Furuyama, A.; Saito, H.; Sawano, T.; Amir, I.; Sato, M.; Kobashi, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yamamoto, C.; et al. Why Do They Not Come Home? Three Cases of Fukushima Nuclear Accident Evacuees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, H.; Orita, M.; Iyama, K.; Sato, N.; Aso, S.; Tateishi, F.; Taira, Y.; Kudo, T.; Yamashita, S.; Takamura, N. Intention to return to the town of Tomioka in residents 7 years after the accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station: A cross-sectional study. J. Radiat. Res. 2019, 60, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, F.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.L.; Chen, J. To stay or to move? Investigation on residents’ migration intention under frequent secondary disasters in Wenchuan earthquake-stricken area. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 920233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Chou, C.; Mostafavi, A. Specifying evacuation return and home-switch stability during short-term disaster recovery using location-based data. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussell, E.; Sastry, N.; Vanlandingham, M. Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Popul. Environ. 2010, 31, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TEPCO. Compensation for Nuclear Damages. Available online: https://www.tepco.co.jp/en/hd/responsibility/revitalization/compensation-e.html (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Boss, P.; Ishii, C. Trauma and Ambiguous Loss: The Lingering Presence of the Physically Absent. In Traumatic Stress and Long-Term Recovery: Coping with Disasters and Other Negative Life Events; Cherry, K.E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. Act on Special Measures for the Reconstruction and Revitalization of Fukushima (Act No. 25 of 2012). Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000192368.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Freak-Poli, R.; Kung, C.S.J.; Ryan, J.; Shields, M.A. Social Isolation, Social Support, and Loneliness Profiles Before and After Spousal Death and the Buffering Role of Financial Resources. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2022, 77, 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawano, T.; Kambe, T.; Seno, Y.; Konoe, R.; Nishikawa, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Shimada, Y.; Morita, T.; Saito, H.; Tsubokura, M. High internal radiation exposure associated with low socio-economic status six years after the Fukushima nuclear disaster: A case report. Medicine 2019, 98, e17989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawano, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Leppold, C.; Takiguchi, M.; Saito, H.; Shimada, Y.; Morita, T.; Tsukada, M.; Ohira, H.; et al. Premature death associated with long-term evacuation among a vulnerable population after the Fukushima nuclear disaster: A case report. Medicine 2019, 98, e16162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Kinoshita, Y.; Morita, T.; Fujioka, S.; Tsubokura, M. Older adult living independently in a public rowhouse project after the 2011 Fukushima earthquake: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Y.; Nakayama, C.; Ito, N.; Moriyama, N.; Iwasa, H.; Yasumura, S. Subjective Wellbeing and Related Factors of Older Adults Nine and a Half Years after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Coastal Area of Soma City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, A.; Morita, T.; Yoshida, I.; Tsubokura, M. Enhancement of PTSD treatment through social support in Idobata-Nagaya community housing after Fukushima’s triple disaster. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, 224935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikichi, H.; Sawada, Y.; Tsuboya, T.; Aida, J.; Kondo, K.; Koyama, S.; Kawachi, I. Residential relocation and change in social capital: A natural experiment from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).