Geriatric Oncology in Portugal: Where We Are and What Comes Next—A Survey of Healthcare Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Development and Setting

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

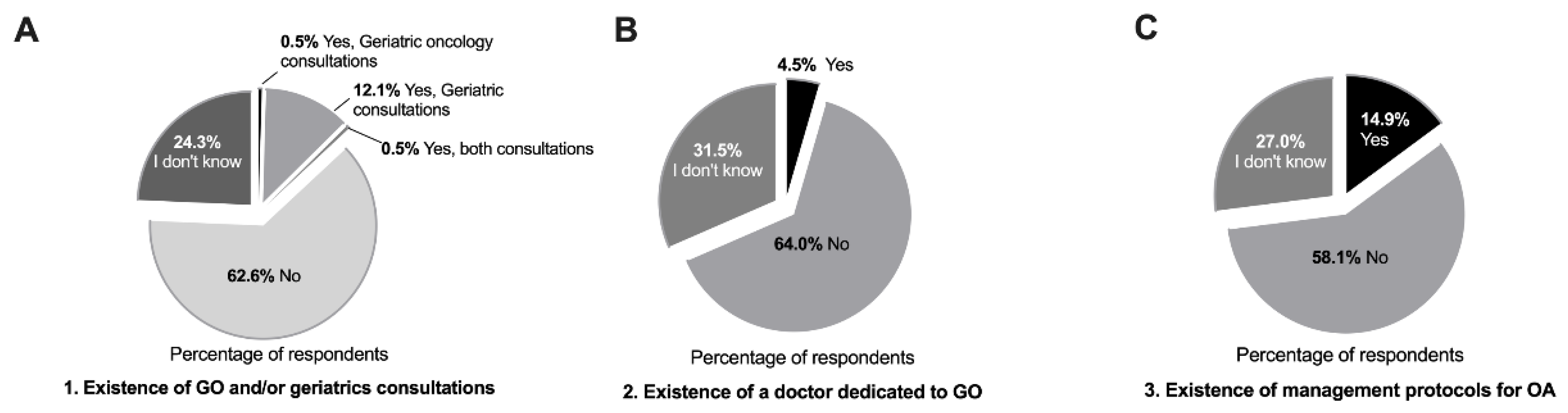

3.1. Facts and Figures—Policies for Older Adults with Cancer

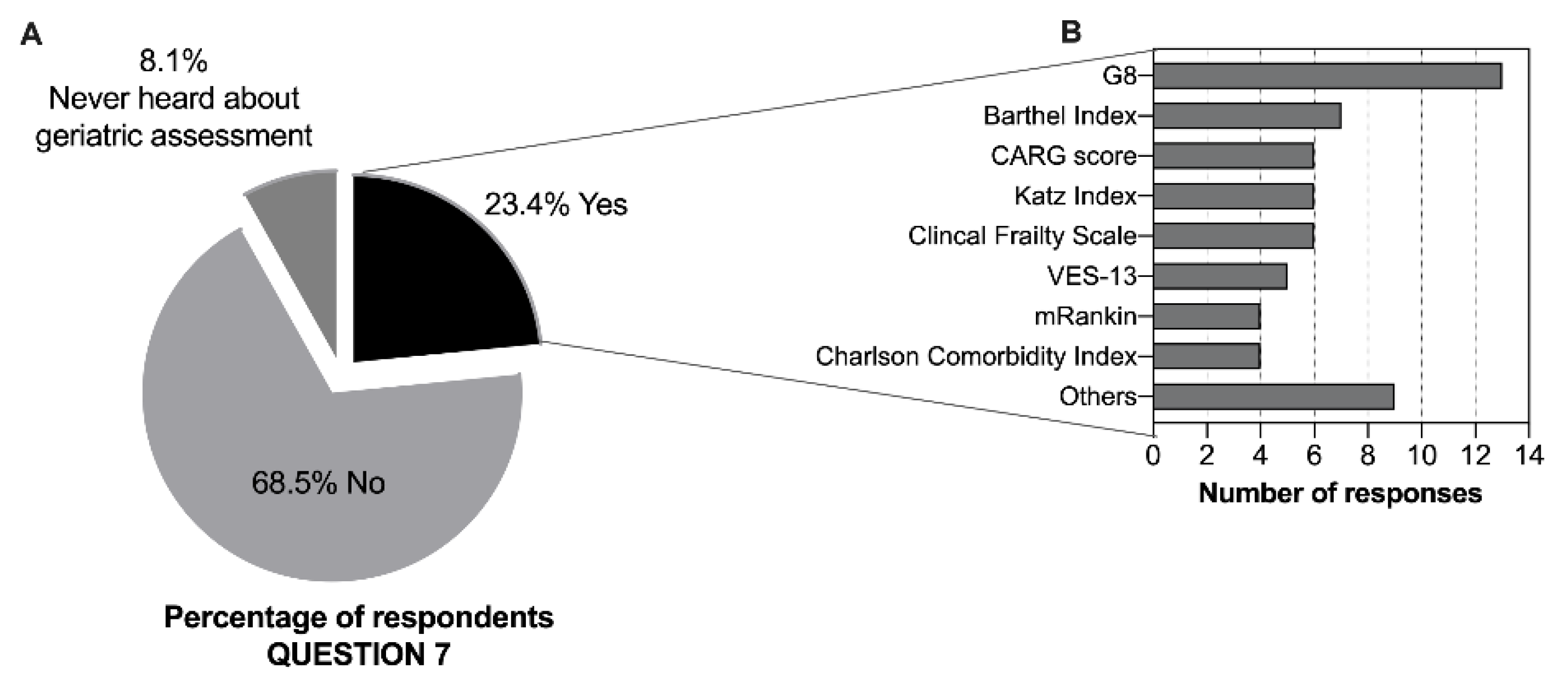

3.2. Geriatric Assessment and Screening

3.3. Decision-Making and Active Aging Initiatives and Policies

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanesvaran, R.; Mohile, S.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Singh, H. The Globalization of Geriatric Oncology: From Data to Practice. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2020, 40, e107–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; de Glas, N.A.; Hsu, T.; Kanesvaran, R.; Steer, C.; Navarrete-Reyes, A.P.; Battisti, N.M.L.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; O’Donovan, A.; Avila-Funes, J.A.; et al. Global geriatric oncology: Achievements and challenges. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2017, 8, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, W.; Williams, G.R.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Maggiore, R.J.; Merrill, J.K.; Katta, S.; Smith, K.T.; Klepin, H.D. How Is Geriatric Assessment Used in Clinical Practice for Older Adults With Cancer? A Survey of Cancer Providers by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. JCO Oncol. Pr. 2021, 17, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.E.; Elias, R.; Plotkin, E.; Lowenstein, L.M.; Swartz, K. Models of Care in Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2195–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, K.P.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Hsu, T.; De Glas, N.A.; Battisti, N.M.L.; Baldini, C.; Rodrigues, M.; Lichtman, S.M.; Wildiers, H. What Every Oncologist Should Know About Geriatric Assessment for Older Patients With Cancer: Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology Position Paper. J. Oncol. Pr. 2018, 14, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Hurria, A. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology Summary. J. Oncol. Pr. 2018, 14, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outlaw, D.; Abdallah, M.; A Gil-Jr, L.; Giri, S.; Hsu, T.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Liposits, G.; Madureira, T.; Marinho, J.; Subbiah, I.M.; et al. The Evolution of Geriatric Oncology and Geriatric Assessment over the Past Decade. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 32, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Hurria, A. Geriatric Assessment and Tools for Predicting Treatment Toxicity in Older Adults With Cancer. Cancer J. 2017, 23, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.M.; Vistisen, K.K.; Olsen, A.P.; Bardal, P.; Schultz, M.; Dolin, T.G.; Rønholt, F.; Johansen, J.S.; Nielsen, D.L. The effect of geriatric intervention in frail older patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: A randomised trial (GERICO). Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, W.-K.; King, M.; Pope, A.; Parente, P.; Darzins, P.; Davis, I.D. Integrated geriatric assessment and treatment (INTEGERATE) in older people with cancer planned for systemic anticancer therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Qian, C.L.; Knight, H.P.; Ferrone, C.R.; Kunitake, H.; Castillo, C.F.-D.; Lanuti, M.; Qadan, M.; Ricciardi, R.; Lillemoe, K.D.; et al. Effects of a perioperative geriatric intervention for older adults with Cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Mohamed, M.R.; Xu, H.; Culakova, E.; Loh, K.P.; Magnuson, A.; A Flannery, M.; Obrecht, S.; Gilmore, N.; Ramsdale, E.; et al. Evaluation of geriatric assessment and management on the toxic effects of cancer treatment (GAP70+): A cluster-randomised study. Lancet 2021, 398, 1894–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, C.-L.; Kim, H.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Chung, V.; Koczywas, M.; Fakih, M.; Chao, J.; Chien, L.C.; Charles, K.; et al. Geriatric Assessment–Driven Intervention (GAIN) on Chemotherapy-Related Toxic Effects in Older Adults With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, e214158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R.; Weaver, K.E.; Lesser, G.J.; Dressler, E.; Winkfield, K.M.; Neuman, H.B.; Kazak, A.E.; Carlos, R.; Gansauer, L.J.; Kamen, C.S.; et al. Capacity to Provide Geriatric Specialty Care for Older Adults in Community Oncology Practices. Oncologist 2020, 25, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EuGMS—European Geriatric Medicine Society. Available online: https://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/portugal.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Bellera, C.A.; Rainfray, M.; Mathoulin-Pélissier, S.; Mertens, C.; Delva, F.; Fonck, M.; Soubeyran, P.L. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, F.; Sousa, N.; Azevedo, L.; Saliba, D. Vulnerability in elderly patients with gastrointestinal cancer—translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the European Portuguese version of the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13). BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, D.; Elliott, M.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; Solomon, D.H.; Young, R.T.; Kamberg, C.J.; Roth, R.C.; MacLean, C.H.; Shekelle, P.G.; Sloss, E.M.; et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: A Tool for Identifying Vulnerable Older People in the Community. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduzco-Aguirre, H.C.; Guerra, L.M.B.; Culakova, E.; Chargoy, J.M.; Martínez-Said, H.; Beulo, G.Q.; Mohile, S.G.; Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E. Barriers and Facilitators for the Implementation of Geriatric Oncology Principles in Mexico: A Mixed-Methods Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e2100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironés, R.; On behalf of the Spanish Working Group on Geriatric Oncology of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM); Morilla, I.; Guillen-Ponce, C.; Torregrosa, M.D.; Paredero, I.; Bustamante, E.; del Barco, S.; Soler, G.; Losada, B.; et al. Geriatric oncology in Spain: Survey results and analysis of the current situation. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 20, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, T.H.; Soo, W.K.; Lane, H.; Khattak, A.; Steer, C.; Devitt, B.; Dhillon, H.M.; Booms, A.; Phillips, J. Utilisation of geriatric assessment in oncology—A survey of Australian medical oncologists. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Perez-De-Celis, E.; Cordoba, R.; Gironés, R.; Karnakis, T.; Paredero, I.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Navarrete-Reyes, A.P.; Avila-Funes, J.A. Cancer and aging in Ibero-America. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 20, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuGMS—European Geriatric Medicine Society. Available online: https://www.eugms.org/our-members/national-societies/spain-segg.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- INE. Censos: INE Statistics Portugal. 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/scripts/db_censos_2021.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Hamaker, M.; Lund, C.; Molder, M.T.; Soubeyran, P.; Wildiers, H.; van Huis, L.; Rostoft, S. Geriatric assessment in the management of older patients with cancer—A systematic review (update). J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, J.; Smorenburg, C.; Schiphorst, A.; Van Rixtel, B.; Portielje, J.; Hamaker, M. Geriatric oncology in the Netherlands: A survey of medical oncology specialists and oncology nursing specialists. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 23, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extermann, M.; Brain, E.; Canin, B.; Cherian, M.N.; Cheung, K.-L.; de Glas, N.; Devi, B.; Hamaker, M.; Kanesvaran, R.; Karnakis, T.; et al. Priorities for the global advancement of care for older adults with cancer: An update of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Priorities Initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e29–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumontier, C.; Loh, K.P.; Bain, P.A.; Silliman, R.A.; Hshieh, T.; Abel, G.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Driver, J.A.; Dale, W. Defining Undertreatment and Overtreatment in Older Adults With Cancer: A Scoping Literature Review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2558–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, C.; Brain, E.; Rostoft, S.; Biganzoli, L.; Goede, V.; Kanesvaran, R.; Quoix, E.; Steer, C.; Papamichael, D.; Wildiers, H. 1827P European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)/International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Joint Working Group (WG) survey on management of older patients with cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S1237–S1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguese Oncology Society. Available online: https://www.sponcologia.pt/pt/grupos-de-trabalho/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

| 1. Does the hospital where you work offer any geriatric oncology and/or geriatrics consultations? |

| 2. In the medical oncology service of the hospital where you work, is there a doctor specifically dedicated to geriatric oncology? |

| 3. Does the hospital where you work have specific management protocols for elderly cancer patients? |

| 4. From your clinical practice, do you perceive that the number of elderly cancer patients (>70 years) has increased? |

| 5. In your opinion, do elderly cancer patients need more specific care when compared to younger patients? |

| 6. Do you feel the need for assessment scales for elderly cancer patients, in addition to ECOG-Performance status and Karnofsky, to help you make treatment decisions? |

| 7. In your clinical practice, do you use any geriatric assessment/screening to evaluate the elderly cancer patients (even if they are not validated for Portuguese language)? |

| 8. Do you think that more information and training in geriatric oncology is needed? |

| 9. How do you think geriatric assessment could help you in your clinical practice? You can choose more than one option. |

| 10. What do you think is important to develop in the field of geriatric oncology in Portugal? You can choose more than one option. |

| Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Number of participants, n | 222 |

| Age, median (years), (min–max) | 36 (78–24) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 151 (68.0) |

| Male | 71 (32.0) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| North | 140 (63.1) |

| Center | 28 (12.6) |

| South | 50 (22.5) |

| Islands (Azores and Madeira) | 4 (1.8) |

| Specialties | |

| Medical oncologist | 119 (53.6) |

| Surgical specialty | 31 (14.0) |

| Internal medicine | 27 (12.2) |

| Radiation oncologists | 12 (5.4) |

| Other specialties | 33 (14.9) |

| Characteristic | Use of GA Tools | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Location, n (%) | ||

| South | 18/50 (36.0) | 0.054 |

| Other locations | 34/172 (19.8) | |

| Specialty | ||

| Medical specialties * | 18/58 (31.0) | 0.009 |

| Medical oncology/Onco-hematology | 18/58 (31.0) | |

| Surgical specialties # | 2/32 (6.3) | |

| Radiation oncologists | 0/12 (0.0) | |

| Responses to Questions 9 and 10 # | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Q9. How do you think geriatric assessment could help you in your clinical practice? | |

| To define a treatment strategy | 189 (85.1) |

| To detect frailty | 172 (77.5) |

| To predict toxicity | 163 (73.4) |

| To improve quality of life | 163 (73.4) |

| To predict survival | 83 (37.4) |

| I do not think GA would help in my clinical practice | 1 (0.5) |

| Q10. What do you think is important to develop in the field of geriatric oncology in Portugal? | |

| Systematic GA in oncology services | 178 (80.2) |

| Invest in training in geriatrics both at the undergraduate and postgraduate level | 156 (70.3) |

| Geriatricians to be part of multidisciplinary teams | 106 (47.7) |

| Creation of study groups in geriatric oncology | 102 (45.9) |

| Creation of geriatric oncology units | 68 (30.6) |

| I do not believe anything is necessary | 1 (0.5) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marinho, J.; Custódio, S. Geriatric Oncology in Portugal: Where We Are and What Comes Next—A Survey of Healthcare Professionals. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050091

Marinho J, Custódio S. Geriatric Oncology in Portugal: Where We Are and What Comes Next—A Survey of Healthcare Professionals. Geriatrics. 2022; 7(5):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarinho, Joana, and Sandra Custódio. 2022. "Geriatric Oncology in Portugal: Where We Are and What Comes Next—A Survey of Healthcare Professionals" Geriatrics 7, no. 5: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050091

APA StyleMarinho, J., & Custódio, S. (2022). Geriatric Oncology in Portugal: Where We Are and What Comes Next—A Survey of Healthcare Professionals. Geriatrics, 7(5), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7050091