Interventions against Social Isolation of Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature and Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

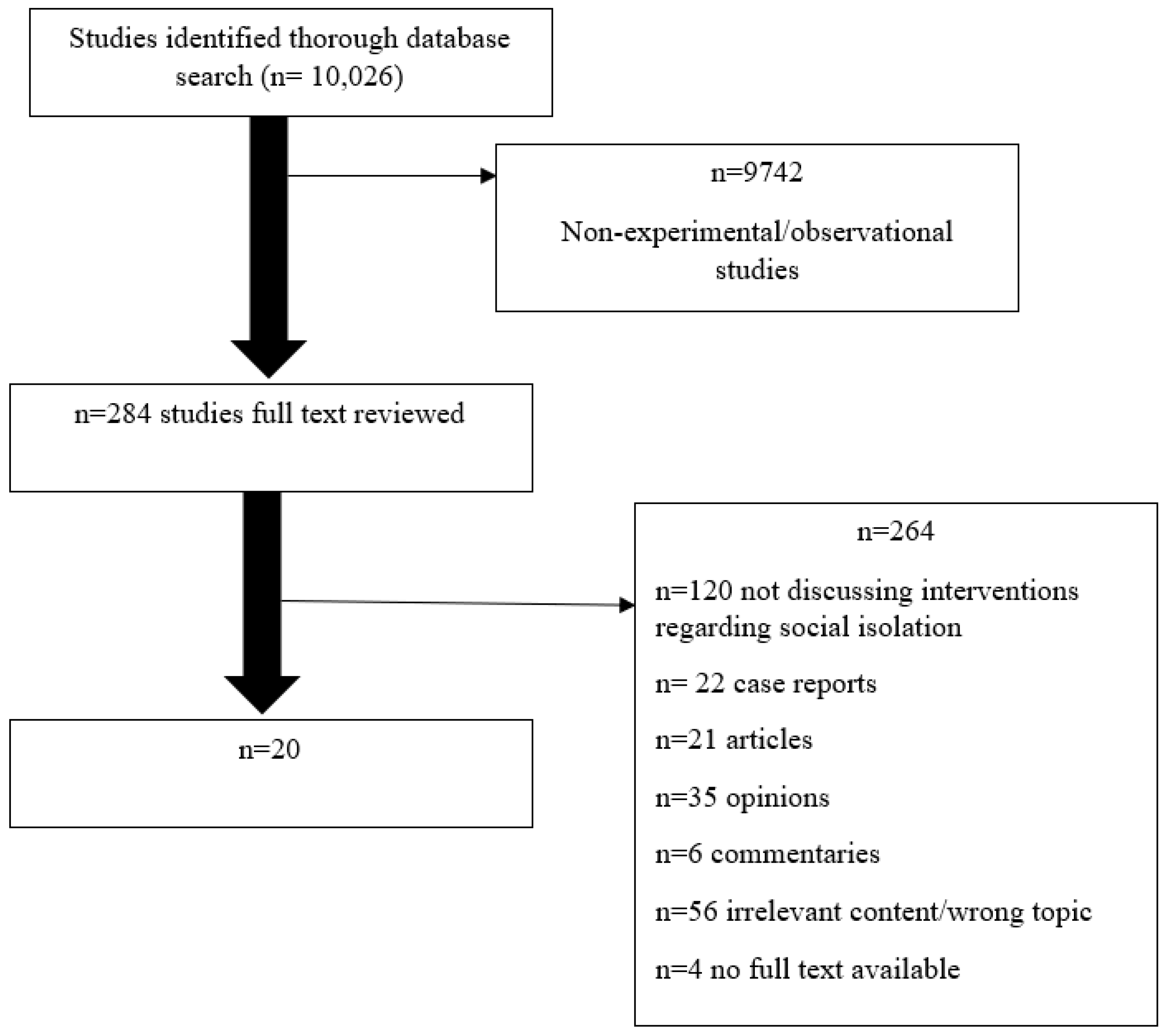

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Search

2.2. Study Selection

- The study was related to older adults above the age of 50 in some way.

- The interventions were targeted towards older adults experiencing loneliness, and a method was proposed to combat isolation.

- The studies recorded an outcome from participants in a study addressing interventions to alleviate social isolation, and outcomes were reported to analyze treatment impacts

- The articles were published in English

- The articles consisted of quasi-experimental, observational or randomized clinical trial studies.

- Community-based approach;

- Psychosocial groups/rehab;

- Friendship enrichment clubs;

- Experimental study on social isolation and interventions;

- Early retirement;

- One-on-one interventions;

- Volunteering.

2.3. Quality Assessment of Studies Included

3. Results

| Intervention Authors, Year | JBI Score | Intervention Effect on Social Isolation/Loneliness Score | Overall Health/Life Satisfaction | Long Term Effectiveness | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteering | |||||

| [14] | 4 | Volunteer increases happiness | Volunteering increase this in men. | Religious volunteering positively impacts female happiness and male life satisfaction. | Gender may affect the effectiveness of volunteering |

| [15] | 9 | N/A | Volunteering decreased cognitive issues and dementia treatment likelihood | Consistent volunteer work is an effective intervention | Intervention effective if consistent |

| Group Interventions | |||||

| [16] | 5 | Life satisfaction, showed insignificant increase | Insignificant increase in overall mental and life satisfaction | Network building showed insignificant increases in quality of life, health. | Insignificant differences, so network building moderate effect. |

| [17] | 5 | Loneliness and isolation scores insignificantly lower than pretest. | Insignificant increases in total support satisfaction, positive affect and decreases in total support needed, and negative affect. | No significant long-term differences. | Insignificant effects in alleviating loneliness. |

| [18] | 6 | Loneliness alleviated and persisted 3 months later. | Groups socially activated participants. | Experiencing things together promoted the sharing of feelings. | Group intervention is effective. |

| [19] | 3 | Improvements shown in mastery, stress and loneliness | Improvements shown in stress, so overall health quality better. | Participants with highest education, significant difference from all but low level. | Community based intervention promote health and independence. |

| [20] | 9 | Meetings positively impact the social support | No improvements shown | No effect on other aspects of social support/loneliness. | Helps with social support but not isolation. |

| [21] | 5 | Social activation increased in the experimental group | Plasma level of testosterone, dehydroepiandosterone & estradiol increased & Hemoglobin A1C decreased. | Larger increase in the first 3 months, but still shows positive changes in 6 months. | Potentially effective program to reduce isolation but can have physiological effects. |

| [22] | 6 | Significantly lower loneliness and higher number of confidants and satisfaction scores | No measures of overall health, but more confidants and satisfaction in experimental groups. | The experimental group had impacts on alleviating loneliness. | This psychosocial group intervention is successful |

| [23] | 9 | Group without intervention experienced a decrease in perceived social support and an increase in perceived loneliness. | No implications on overall health. | Intervention did not improve loneliness in experimental group. | Not most effective intervention, but may increase cognitive functioning, and decrease depression |

| [10] | 7 | Improvement in well being lasts at least 3 months | Improvement in health and life satisfaction | Need to study long term effects, no data to support it. | Seems beneficial intervention, but need long-term studies |

| [12] | 7 | Participants gained social support | Mean subjective well-being scores higher for intervention group | Loneliness scale score decreased after the program and 6 months later | Community based programs allowing shared experiences have potential for success |

| Friendship Centred Interventions | |||||

| [24] | 7 | Older people value being in a community and independence to make connections. | Improved well-being, social Relations, mental/physical health | Friendship clubs address all areas, but need more research | Friendship clubs beneficial, but observational, so researcher influence |

| [25] | 6 | Overall alleviates immediate loneliness, but no decline over course. | Social and emotional loneliness, declined over study course | Immediate benefit but no loneliness decline long term. | Overall, help alleviate loneliness, no direct decline. |

| Person Centred/One-on-One Intervention | |||||

| [13] | 7 | Associated with feeling of control related to loneliness – older adults with more control may be able to cope with social isolation. | Life satisfaction is related to the psychosocial needs of residents | May have long term effects if given control and choice over their schedule. | Fulfilling preferences are an appropriate intervention for social isolation. |

| [26] | 7 | Some improvement in mental health scores, statistically insignificant. | Some form of improvement in mental health. | No statistical difference between intervention and control groups. | Peer telephone dyads were not an effective intervention |

| [11] | 6 | Participants receiving a friendly visitor showed a statistically significant difference in satisfaction | Clinical improvements occurred in the level of health. | Extensive research needed to verify program effectiveness. | Seems effective intervention but need long term research. |

| [27] | 8 | Significantly better health after visits only in the subgroup with poor health at baseline. | Benefits can be gained from home visits if health problems already present | Need long term research; effective for those with pre-existing conditions. | Only beneficial to those with pre-existing problems, can’t generalize. |

| Health Promoting/Social Support Interventions | |||||

| [28] | 9 | Positive effect of health-promoting interventions on older adults’ lifestyle. | Significant difference in total average scores of lifestyle between intervention and control groups. | Improvement in lifestyle conditions predicted to be long term but need to investigate further. | Beneficial intervention to improve lifestyle of older adults |

| [29] | 6 | Significantly less loneliness and more social support and well-being at 6 months, but no statistically significant difference at 12 months | Increase in computer comfort, efficacy and proficiency. | No statistically significant difference at 12 months, so long term effects minimal. | PRISM is a good tool for social connectivity but may only be a short term intervention. |

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simard, J.; Volicer, L. Loneliness and isolation in long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 966–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R.L.; Cassells, J.S. Social isolation among older individuals: The relationship to mortality and morbidity. In The Second Fifty Years: Promoting Health and Preventing Disability; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, N.R. A review of social isolation: An important but underassessed condition in older adults. J. Prim. Prev. 2012, 33, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Colaço Harmand, M.; Meillon, C.; Rullier, L.; Avila-Funes, J.A.; Bergua, V.; Dartigues, J.F.; Amieva, H. Cognitive decline after entering a nursing home: A 22-year follow-up study of institutionalized and noninstitutionalized elderly people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Mao, F.; Zhang, W.; Towne, S.D., Jr.; Wang, P.; Fang, Y. The Association Between Loneliness and Cognitive Impairment among Older Men and Women in China: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Loyola, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.; Perez-Rodriguez, P.; Ganz, F.; Torralba, R.; Oliveira, D.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://joannabriggs.org/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Lökk, J. Emotional and social effects of a controlled intervention study in a day-care unit for elderly patients. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 1990, 8, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, I.; Corradetti, P.; Roberts, J.; Browne, G.; Watt, S.; Lane, A. Pilot study of a visitor volunteer programme for community elderly people receiving home health care. Health Soc. Care Community 1999, 7, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Kai, I.; Takizawa, A. Effects of a program to prevent social isolation on loneliness, depression, and subjective well-being of older adults: A randomized trial among older migrants in Japan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 55, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, N.; Meeks, S. Fulfilled preferences, perceived control, life satisfaction, and loneliness in elderly long-term care residents. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Lacruz, M.; Saz-Gil, M.I.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I. Benefits of Older Volunteering on Wellbeing: An International Comparison. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griep, Y.; Hanson, L.M.; Vantilborgh, T.; Janssens, L.; Jones, S.K.; Hyde, M. Can volunteering in later life reduce the risk of dementia? A 5-year longitudinal study among volunteering and non-volunteering retired seniors. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogat, G.A.; Jason, L.A. An evaluation of two visiting programs for elderly community residents. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1983, 17, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Craig, D.; MacPherson, K.; Alexander, S. Promoting positive affect and diminishing loneliness of widowed seniors through a support intervention. Public Health Nurs. 2001, 18, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savikko, N.; Routasalo, P.; Tilvis, R.; Pitkälä, K. Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: Favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2010, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, C.C.; Benedict, J. Evaluation of a Community-based Health Promotion Program for the Elderly: Lessons from Seniors CAN. Am. J. Health Promot. 2006, 21, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, S.; Berglund, H.; Faronbi, J.; Barenfeld, E.; Ottenvall Hammar, I. Minor positive effects of health-promoting senior meetings for older community-dwelling persons on loneliness, social network, and social support. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, B.B.; Theorell, T.; Levi, L.; Kallner, A.; Eneroth, P. An experimental study of social isolation of elderly people: Psychoendocrine and metabolic effects. Psychosom. Med. 1983, 45, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, S.; Koike, M.; Ooba, A.; Uchitomi, Y. The effect of a psychosocial group intervention on loneliness and social support for Japanese women with primary breast cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2003, 30, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winningham, R.; Pike, N.L. A cognitive intervention to enhance institutionalized older adults’ social support networks and decrease loneliness. Aging Ment. Health 2007, 11, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, A.; Jack, E. Reducing social isolation and promoting well being in older people. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2013, 14, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, T.E.; Aartsen, M.J.; van Tilburg, T.G.; Stevens, N.L. Does stimulating various coping strategies alleviate loneliness? Results from an online friendship enrichment program. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 34, 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K.; Thompson, M.G.; Trueba, P.E.; Hogg, J.R.; Vlachos-Weber, I. Peer support telephone dyads for elderly women: Was this the wrong intervention? Am. J. Community Psychol. 1991, 19, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rossum, E.; Frederiks, C.; Philipsen, H.; Portengen, K.; Wiskerke, J.; Knipschild, P. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people. Br. Med. J. 1993, 307, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi Foroushani, A.; Estebsari, F.; Mostafaei, D.; Eftekhar Ardebili, H.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Dastoorpour, M.; Jamshidi, E.; Taghdisi, M.H. The effect of health promoting intervention on healthy lifestyle and social support in elders: A clinical trial study. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e18399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, S.J.; Boot, W.R.; Charness, N.; Rogers, W.A.; Sharit, J. Improving Social Support for Older Adults Through Technology: Findings From the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office, E.E.; Rodenstein, M.S.; Merchant, T.S.; Pendergrast, T.R.; Lindquist, L.A. Reducing Social Isolation of Seniors during COVID-19 through Medical Student Telephone Contact. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manjunath, J.; Manoj, N.; Alchalabi, T. Interventions against Social Isolation of Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature and Interventions. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6030082

Manjunath J, Manoj N, Alchalabi T. Interventions against Social Isolation of Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature and Interventions. Geriatrics. 2021; 6(3):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6030082

Chicago/Turabian StyleManjunath, Jaya, Nandita Manoj, and Tania Alchalabi. 2021. "Interventions against Social Isolation of Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature and Interventions" Geriatrics 6, no. 3: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6030082

APA StyleManjunath, J., Manoj, N., & Alchalabi, T. (2021). Interventions against Social Isolation of Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature and Interventions. Geriatrics, 6(3), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6030082