Prevalence of Swallowing and Eating Difficulties in an Elderly Postoperative Hip Fracture Population—A Multi-Center-Based Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

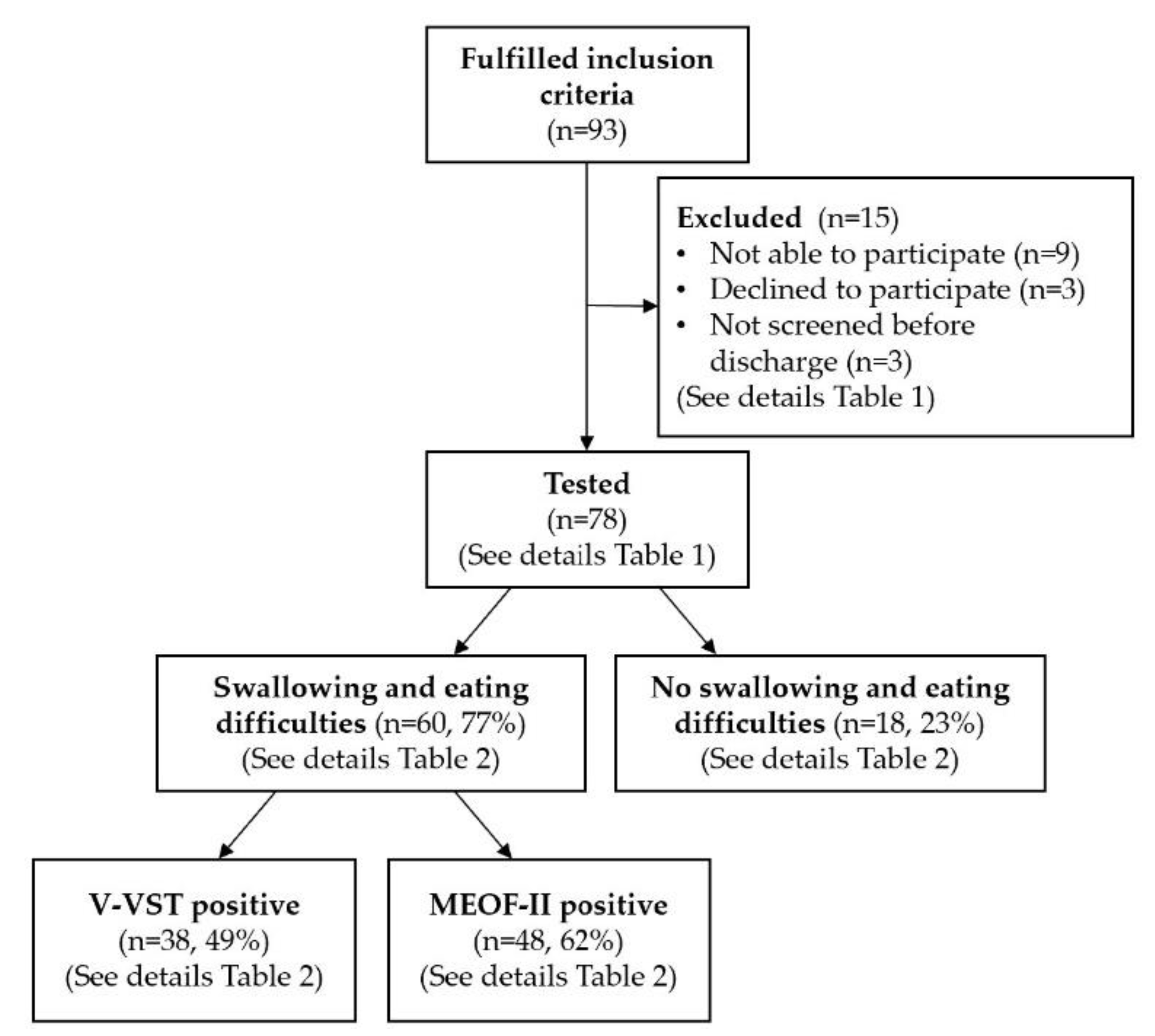

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Patient Sample

2.2. Swallowing and Eating Assessment

2.3. Other Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Baijens, L.W.; Clave, P.; Cras, P.; Ekberg, O.; Forster, A.; Kolb, G.F.; Leners, J.C.; Masiero, S.; Mateos-Nozal, J.; Ortega, O.; et al. European Society for Swallowing Disorders—European Union Geriatric Medicine Society white paper: Oropharyngeal dysphagia as a geriatric syndrome. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1403–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Kjaersgaard, A.; Faber, J. Measuring elderly dysphagic patients’ performance in eating—A review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 1931–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westergren, A.; Lindholm, C.; Mattsson, A.; Ulander, K. Minimal eating observation form: Reliability and validity. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, B.R.; Lagaay, A.M.; van Beek, W.; Haan, J.; Roos, R.A.; Wintzen, A.R. Prevalence of subjective dysphagia in community residents aged over 87. BMJ 1990, 300, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaro-Moreira, N.C.; Krausch-Hofmann, S.; Matthys, C.; Vereecken, C.; Vanhauwaert, E.; Declercq, A.; Bekkering, G.E.; Duyck, J. Risk Factors for Malnutrition in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature Based on Longitudinal Data. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmore, S.E.; Terpenning, M.S.; Schork, A.; Chen, Y.; Murray, J.T.; Lopatin, D.; Loesche, W.J. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: How important is dysphagia? Dysphagia 1998, 13, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgaard, D.; Rodrigo-Domingo, M.; Mørch, M.M. The Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Acute Geriatric Patients. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.M.; Maribo, T.; Westergren, A.; Melgaard, D. Associations between eating difficulties, nutritional status and activity of daily living in acute geriatric patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2018, 25, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Prat, M.; Hinojosa, G.; Lopez, D.; Juan, M.; Fabre, E.; Voss, D.S.; Calvo, M.; Marta, V.; Ribo, L.; Palomera, E.; et al. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia and impaired safety and efficacy of swallow in independently living older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. National Klinisk Retningslinje for øvre Dysfagi—Opsporing, Udredning og Udvalgte Indsatser. 2015. Available online: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2015/~/media/7E4C638B32204D5F97BCB9805D12C32F.ashx (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Barczi, S.R.; Sullivan, P.A.; Robbins, J. How should dysphagia care of older adults differ? Establishing optimal practice patterns. Semin Speech Lang. 2000, 21, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, D.W. Neurogenic dysphagia: What is the cause when the cause is not obvious? Dysphagia 1994, 9, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, I.J. Oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 38, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, P.; Drinnan, M.J.; Ford, G.A.; Wilson, J.A. Swallow respiratory patterns and aging: Presbyphagia or dysphagia? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2005, 60, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Logemann, J.A.; Curro, F.A.; Pauloski, B.; Gensler, G. Aging effects on oropharyngeal swallow and the role of dental care in oropharyngeal dysphagia. Oral Dis. 2013, 19, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ney, D.M.; Weiss, J.M.; Kind, A.J.; Robbins, J. Senescent swallowing: Impact, strategies, and interventions. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2009, 24, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofes, L.; Arreola, V.; Romea, M.; Palomera, E.; Almirall, J.; Cabre, M.; Serra-Prat, M.; Clave, P. Pathophysiology of oropharyngeal dysphagia in the frail elderly. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrion, S.; Cabre, M.; Monteis, R.; Roca, M.; Palomera, E.; Serra-Prat, M.; Rofes, L.; Clave, P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a prevalent risk factor for malnutrition in a cohort of older patients admitted with an acute disease to a general hospital. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslick, G.D.; Talley, N.J. Dysphagia: Epidemiology, risk factors and impact on quality of life-a population-based study. Aliment. Pharm. Ther. 2008, 27, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melgaard, D.; Baandrup, U.; Bøgsted, M.; Bendtsen, M.D.; Hansen, T. Rehospitalisation and mortality after hospitalisation for orapharyngeal dysphagia and community-acquired pneumonia: A 1-year follow-up study. Cogent Med. 2017, 4, 1417668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puisieux, F.; D’Andrea, C.; Baconnier, P.; Bui-Dinh, D.; Castaings-Pelet, S.; Crestani, B.; Desrues, B.; Ferron, C.; Franco, A.; Gaillat, J.; et al. Swallowing disorders, pneumonia and respiratory tract infectious disease in the elderly. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2011, 28, e76–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maarel-Wierink, C.D.; Vanobbergen, J.N.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Schols, J.M.; de Baat, C. Meta-analysis of dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia in frail elders. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, K.W.; Yu, G.P.; Schaefer, S.D. Consequence of dysphagia in the hospitalized patient: Impact on prognosis and hospital resources. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 136, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westmark, S.; Melgaard, D.; Rethmeier, L.O.; Ehlers, L.H. The cost of dysphagia in geriatric patients. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2018, 10, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Maggi, S. Epidemiology and social costs of hip fracture. Injury 2018, 49, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansk Tværfagligt Register for Hoftenære Lårbensbrud. National Årsrapport. 2018. Available online: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/62/4662_dansk-tvaerfaglig-register-for-hoftenaere-laarbensbrud.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Hu, F.; Jiang, C.; Shen, J.; Tang, P.; Wang, Y. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2012, 43, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Hossain, F.S.; Ahmed, I.; Muthukumar, N.; Mohsen, A. Predictors of early mortality after hip fracture surgery. Int. Orthop. 2013, 37, 2119–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, H.Q.; Hossain, F.S.; Aqil, A.; Akinbamijo, B.; Mushtaq, V.; Kapoor, H. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Causes and Predictors of 30-Day Mortality Following Hip Fracture Surgery. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 9, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, B.; van Staa, T.; Ariely, R.; Olson, M.; Cooper, C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: A systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.A.; Moller, A.M.; Wetterslev, J.; Lundstrom, L.H. Organizational factors and long-term mortality after hip fracture surgery. A cohort study of 6143 consecutive patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Konig, H.H.; Rapp, K.; Becker, C.; Rothenbacher, D.; Buchele, G. Analysis of mortality after hip fracture on patient, hospital, and regional level in Germany. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, S.L.; Behrend, C.; Mendelson, D.A.; Cram, P.; Friedman, S.M. Hospital readmission after hip fracture. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2015, 135, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Hossain, F.S.; Dashti, Z.; Muthukumar, N. Causes and predictors of early re-admission after surgery for a fracture of the hip. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2012, 94, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizaur-Utrilla, A.; Serna-Berna, R.; Lopez-Prats, F.A.; Gil-Guillen, V. Early rehospitalization after hip fracture in elderly patients: Risk factors and prognosis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2015, 135, 1663–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgaard, D.; Baandrup, U.; Bøgsted, M.; Bendtsen, M.D.; Hansen, T. The Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Danish Patients Hospitalised with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beric, E.; Smith, R.; Phillips, K.; Patterson, C.; Pain, T. Swallowing disorders in an older fractured hip population. Aust. J. Rural Health 2019, 27, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.E.; Kwon, K.B.; Kim, S.H.; Lim, S.J. The prevalence, risk factors and prognostic implications of dysphagia in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery in Korea. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.L.; Cornwell, P.L.; Whitehouse, S.L. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in an elderly post-operative hip fracture population: A prospective cohort study. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meals, C.; Roy, S.; Medvedev, G.; Wallace, M.; Neviaser, R.J.; O’Brien, J. Identifying the Risk of Swallowing-Related Pulmonary Complications in Older Patients with Hip Fracture. Orthopedics 2016, 39, e93–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clave, P.; Arreola, V.; Romea, M.; Medina, L.; Palomera, E.; Serra-Prat, M. Accuracy of the volume-viscosity swallow test for clinical screening of oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, L.W.; Søndergaard, K.; Melgaard, D.; Warming, S. Interrater reliability of the Volume-Viscosity Swallow Test; screening for dysphagia among hospitalized elderly medical patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 22, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofes, L.; Arreola, V.; Mukherjee, R.; Clave, P. Sensitivity and specificity of the Eating Assessment Tool and the Volume-Viscosity Swallow Test for clinical evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westergren, A. The Minimal Eating Observation Form-Version II Revisited: Validity and Reliability. J. Nurs. Meas. 2019, 27, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westergren, A.; Melgaard, D. The Minimal Eating Observation Form-II Danish Version: Psychometric and Metrological Aspects. J. Nurs. Meas. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrink, E.; Jildenstal, P.; Oddby, E.; Jakobsson, J.G. Post-operative nausea and vomiting: Update on predicting the probability and ways to minimize its occurrence, with focus on ambulatory surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 15, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga-Gil, L.; Pueyo, J.; Lopez-Olaondo, L. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: Physiopathology, risk factors, prophylaxis and treatment. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2017, 64, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.T.; Bandholm, T.; Foss, N.B.; Ekdahl, C.; Kehlet, H. High inter-tester reliability of the new mobility score in patients with hip fracture. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M.; Greenwood, C.; Ens, I.; Robertson, C.; Seidman-Carlson, R. Mealtime difficulties in a home for the aged: Not just dysphagia. Dysphagia 1997, 12, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, C.; Wolter, S.; Schauer, T.; Nahrstaedt, H.; Seidl, R.O. Effect of body position on coordination of breathing and swallowing. HNO 2015, 63, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Zafar, H.; Al-Eisa, E.S.; Iqbal, Z.A. Effect of posture on swallowing. Afr. Health Sci. 2017, 17, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo-Cadavid, L.F.; Leal-Leano, L.R.; Leon-Basantes, G.A.; Bastidas, A.R.; Garcia, R.; Ovalle, S.; Abondano-Garavito, J.E. Accuracy of endoscopic and videofluoroscopic evaluations of swallowing for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertscher, B.; Speyer, R.; Palmieri, M.; Plant, C. Bedside screening to detect oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with neurological disorders: An updated systematic review. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bours, G.J.; Speyer, R.; Lemmens, J.; Limburg, M.; de Wit, R. Bedside screening tests vs. videofluoroscopy or fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing to detect dysphagia in patients with neurological disorders: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, D.; Smithard, D.; Kalra, L. Silent aspiration: What do we know? Dysphagia 2005, 20, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly-Pettersson, P.; Samuelsson, B.; Muren, O.; Unbeck, M.; Gordon, M.; Stark, A.; Sköldenberg, O.; Kristensen, M.T.; Jakobsen, T.L.; Nielsen, J.W.; et al. Waiting time to surgery is correlated with an increased risk of serious adverse events during hospital stay in patients with hip-fracture: A cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 69, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.T.; Jakobsen, T.L.; Nielsen, J.W.; Jørgensen, L.M.; Nienhuis, R.J.; Jønsson, L.R. Cumulated Ambulation Score to evaluate mobility is feasible in geriatric patients and in patients with hip fracture. Dan. Med. J. 2012, 59, A4464. [Google Scholar]

| Population Variable | Patients Screened (n = 78) | Patients Not Screened (n = 15) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.484 | ||

| Male | 24 (30.8) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Female | 54 (69.2) | 9 (60.0) | |

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 81.4 (7.8) | 82.7 (10.9) | 0.592 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 166.7 (10.6) | 169.1 (10.4) | 0.416 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 67.5 (14.9) | 65.8 (12.6) | 0.695 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 24.3 (4.3) | 23.0 (4.3) | 0.320 |

| Habitual housing form | 0.048 | ||

| Own residence | 62 (79.5) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Nursing home | 16 (20.5) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Neurological comorbidity | 27 (34.6) | 8 (53.3) | 0.244 |

| Respiratory comorbidity | 19 (24.4) | 4 (26.7) | 1.000 |

| Cardiac comorbidity | 47 (60.3) | 5 (33.3) | 0.087 |

| Ear, nose, or throat comorbidity | 6 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 1.000 |

| Other comorbidity | 69 (88.5) | 13 (86.7) | 1.000 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score | 0.360 | ||

| ASA I | 2 (3.3) | 1 (12.5) | |

| ASA II | 27 (45.0) | 3 (37.5) | |

| ASA III | 29 (48.3) | 4 (50.0) | |

| ASA IV | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.7) | 0.557 |

| Delirium | 0.024 | ||

| Yes | 1 (5.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

| No | 19 (95.0) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Habitual New Mobility Score | 0.394 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 | 3 (6.8) | 1 (33.3) | |

| 3 | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 6 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 5 | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 6 | 7 (15.9) | 2 (66.7) | |

| 7 | 5 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 8 | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 9 | 13 (29.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.0 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.3) | 0.385 |

| Habitual swallowing difficulties | 0.112 | ||

| Yes | 3 (4.4) | 1 (10.0) | |

| No | 65 (95.6) | 9 (90.0) | |

| Fracture type | 0.157 | ||

| Pertrochanteric | 36 (46.2) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Subtrochanteric | 5 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Collum | 37 (47.4) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Time from admission to surgery (hours), mean (SD) | 12.7 (9.8) | 18.9 (10.8) | 0.030 |

| Type of anesthesia | 0.006 | ||

| General | 36 (46.2) | 9 (60.0) | |

| Spinal | 40 (51.3) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Other kind/unknown | 2 (2.6) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Surgery type | 0.342 | ||

| Arthroplasty | 25 (32.1) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Intramedullary nail | 17 (21.8) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Dynamic hip screw | 29 (37.2) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Splint | 7 (9.0) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Time from surgery to swallowing and eating assessment (hours), mean (SD) | 30.4 (19.0) | ||

| Cumulated Ambulation Score day 1 after surgery | 0.003 | ||

| 0 | 1 (1.5) | 2 (20.0) | |

| 1 | 2 (2.9) | 1 (10.0) | |

| 2 | 23 (33.8) | 2 (20.0) | |

| 3 | 27 (39.7) | 1 (10.0) | |

| 4 | 5 (7.4) | 2 (20.0) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | |

| 6 | 10 (14.7) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.4) | 2.7 (2.1) | 0.467 |

| Population Variable | Swallowing and Eating Difficulties (n = 60) | No Swallowing and Eating Difficulties (n = 18) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.754 | ||

| Male | 19 (31.7) | 5 (27.8) | |

| Female | 41 (68.3) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 81.1 (8.2) | 82.4 (6.5) | 0.544 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 166.2 (10.8) | 168.3 (10.1) | 0.483 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 66.7 (16.0) | 69.8 (10.9) | 0.442 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 24.0 (4.4) | 25.3 (4.0) | 0.267 |

| Habitual housing form | 0.014 | ||

| Own residence | 44 (73.3) | 18 (100.0) | |

| Nursing home | 16 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Volume-Viscosity swallow test | 38 (63.3) | ||

| Impaired safety | 17 (28.3) | ||

| Impaired efficacy | 32 (53.3) | ||

| Minimal Eating Observation Form-II | 48 (80.0) | ||

| Ingestion | 48 (80.0) | ||

| Sitting position | 38 (63.3) | ||

| Manipulation of food on the plate | 23 (38.3) | ||

| Transport of food to the mouth | 22 (36.7) | ||

| Deglutition | 38 (63.3) | ||

| Manipulation of food in the mouth | 22 (36.7) | ||

| Swallowing | 27 (45.0) | ||

| Ability to chew | 30 (50.0) | ||

| Energy/appetite a | 19 (31.7) | ||

| Comorbidity | |||

| Neurological comorbidity | 24 (40.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0.068 |

| Respiratory comorbidity | 16 (26.7) | 3 (16.7) | 0.386 |

| Cardiac comorbidity | 32 (53.3) | 15 (83.3) | 0.023 |

| Ear, nose, or throat comorbidity | 5 (8.3) | 1 (5.6) | 0.698 |

| Other comorbidity | 55 (91.7) | 14 (77.8) | 0.106 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score | 0.489 | ||

| ASA I | 1 (2.3) | 1 (6.3) | |

| ASA II | 18 (40.9) | 9 (56.3) | |

| ASA III | 23 (52.3) | 6 (37.5) | |

| ASA IV | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) | 0.128 |

| Delirium | 0.532 | ||

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 16 (94.1) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Habitual New Mobility Score | 0.320 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 3 | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 4 (12.5) | 2 (16.7) | |

| 5 | 2 (6.3) | 1 (8.3) | |

| 6 | 6 (18.8) | 1 (8.3) | |

| 7 | 4 (12.5) | 1 (8.3) | |

| 8 | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 9 | 6 (18.8) | 7 (58.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.5) | 7.4 (2.1) | 0.018 |

| Habitual swallowing difficulties | 0.595 | ||

| Yes | 3 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 49 (94.2) | 16 (100.0) | |

| Fracture type | 0.964 | ||

| Pertrochanteric | 28 (46.7) | 8 (44.4) | |

| Subtrochanteric | 4 (6.7) | 1 (5.6) | |

| Collum | 28 (46.7) | 9 (50.0) | |

| Time from admission to surgery (hours), mean (SD) | 13.2 (9.8) | 11.1 (9.7) | 0.422 |

| Type of anesthesia | 0.520 | ||

| General | 29 (48.3) | 7 (38.9) | |

| Spinal | 29 (48.3) | 11 (61.1) | |

| Other kind/unknown | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Surgery type | 0.285 | ||

| Arthroplasty | 20 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | |

| Intramedullary nail | 15 (25.0) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Dynamic hip screw | 19 (31.7) | 10 (55.6) | |

| Splint | 6 (10.0) | 1 (5.6) | |

| Time from surgery to swallowing and | 30.5 (19.5) | 29.8 (22.4) | 0.894 |

| eating assessment (hours), mean (SD) | |||

| Cumulated Ambulation Score day 1 after surgery | 0.933 | ||

| 0 | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 | 18 (34.6) | 5 (31.3) | |

| 3 | 20 (38.5) | 7 (43.8) | |

| 4 | 4 (7.7) | 1 (6.3) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 6 | 7 (13.5) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.5) | 0.445 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madsen, G.; Kristoffersen, S.M.; Westergaard, M.R.; Gjødvad, V.; Jessen, M.M.; Melgaard, D. Prevalence of Swallowing and Eating Difficulties in an Elderly Postoperative Hip Fracture Population—A Multi-Center-Based Pilot Study. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics5030052

Madsen G, Kristoffersen SM, Westergaard MR, Gjødvad V, Jessen MM, Melgaard D. Prevalence of Swallowing and Eating Difficulties in an Elderly Postoperative Hip Fracture Population—A Multi-Center-Based Pilot Study. Geriatrics. 2020; 5(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics5030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadsen, Gitte, Stine M. Kristoffersen, Mark R. Westergaard, Vivi Gjødvad, Merete M. Jessen, and Dorte Melgaard. 2020. "Prevalence of Swallowing and Eating Difficulties in an Elderly Postoperative Hip Fracture Population—A Multi-Center-Based Pilot Study" Geriatrics 5, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics5030052

APA StyleMadsen, G., Kristoffersen, S. M., Westergaard, M. R., Gjødvad, V., Jessen, M. M., & Melgaard, D. (2020). Prevalence of Swallowing and Eating Difficulties in an Elderly Postoperative Hip Fracture Population—A Multi-Center-Based Pilot Study. Geriatrics, 5(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics5030052