1. Introduction

Obesity has rapidly increased, particularly among lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups in many low and middle-income countries [

1]. While a substantial amount of literature relates obesity to cardiometabolic disease risk in low and middle-income countries, relatively little attention has been paid to how obesity relates to functional outcomes and well-being in these settings. For example, in several systematic reviews that identified numerous prospective studies relating obesity to physical disability, all but one of the cited studies were from high income countries [

2,

3].

Longitudinal studies in high income settings among older adults have found that overweight and obesity are associated with increased odds of developing disabilities. For example, obesity and high WC increased the odds of six-year disability incidence in Dutch adults aged 55 and older [

4] and in the US Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Cohort, obesity at age 25 was associated with increased odds of functional limitations and ADL and IADL impairments later in life [

5]. In the Health ABC study, an 8-fold higher risk of incident mobility limitations after age 70 was reported among individuals who were obese since age 25 [

6]. In a systematic review, Vincent et al., it was reported that mobility disability (walking, stair climbing, and chair rise ability) was more prevalent with obesity in adults 60 years old and above, and in particular, when BMI exceeded 35 kg/m

2 [

7]. Rejeski and colleagues in their review [

2] also noted non-linear effects of BMI, which emphasize the need for studies to examine BMI or high WC categories.

There are several pathways through which obesity may affect physical functioning [

2,

3]. Excess body weight may directly affect joints and increase risk of osteoarthritis, or alter movement dynamics, postural control, and pain and thus influence mobility [

3,

6]. The combination of obesity and muscle weakness also relates to functional limitations [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Obesity may also increase risk of disability indirectly through its well-known association with chronic diseases, with well-documented associations of diabetes with disability [

10,

12,

13,

14,

15].

At the same time, physical/mobility limitations may contribute to a more sedentary lifestyle, which, in turn, may lead to weight gain. The relationship of obesity to functional limitations is therefore difficult to understand without using high quality longitudinal data to address the direction of associations and pathways.

Since 1983, the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey (CLHNS) has collected detailed data from a community-based cohort of women and an index offspring [

16]. The CLHNS includes residents of cities and contiguous peri-urban and rural areas that comprise Metro Cebu, the second largest metropolitan area of the Philippines. Metro Cebu exemplifies current demographic and health trends in Asia, where populations are aggregating into rapidly expanding urban centers, levels of economic growth are high, and cardiovascular and related diseases have become the leading cause of mortality. According to 2016 data, heart disease, stroke, and diabetes were the top three conditions responsible for death and disability in the Philippines [

17]. Our past research in the CLHNS sample documented a dramatic 7-fold increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI > 25 kg/m

2) from 1986 to 2002 (from 6.5% to 42% of adult women), and a doubling of hypertension prevalence (SBP ≥ 140 or DBP ≥ 90) from 19% to 38% between 1998 and 2007 [

18].

Here, we aimed to investigate how overweight and obesity relate to physical capacity (grip strength and timed up-and-go) and to the development of self-reported physical/mobility limitations, activities of daily living (ADLs), and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) using data from repeated surveys in the CLHNS cohort. Since the CLHNS includes women across a wide age range, we also assess how these relationships differ by age and over time. We test whether self-reported chronic disease morbidity (elevated blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis, cancer, and heart disease) may mediate a hypothesized association of obesity with disabilities. Moreover, many studies of functional status focus on the elderly and ignore the early development of functional limitations among younger adults.

4. Discussion

Owing to their relatively young age in 1994, CLHNS participants had a low initial incidence and prevalence of disabilities, but following them for more than 20 years, we were able to observe incident functional limitations associated with age, time, urbanicity, and central obesity. Incident functional limitations increased most sharply after age 60. Physical/mobility limitations were the most prevalent, and among the ADL and IADL tasks, those that required some physical effort (standing, child care, using public transportation) were more prevalent than those requiring less physical effort.

Our repeated measures design and focus on recurrent and incident functional limitations are a key strength of our study. Since having a mobility limitation may decrease physical activity, which in turn contributes to overweight and obesity, our use of lagged measures avoids the potential bias associated with the use of concurrently measured exposures and outcomes.

We found that lagged WC was associated with increased likelihood of any incident physical/mobility limitations across all age groups. Thus, central obesity is an important risk factor for development of mild disability regardless of age. We defined incident disability as reporting a disability at the current survey, but not in the prior one. This allows us to examine recurrent cases as women gain weight and waist circumference over time.

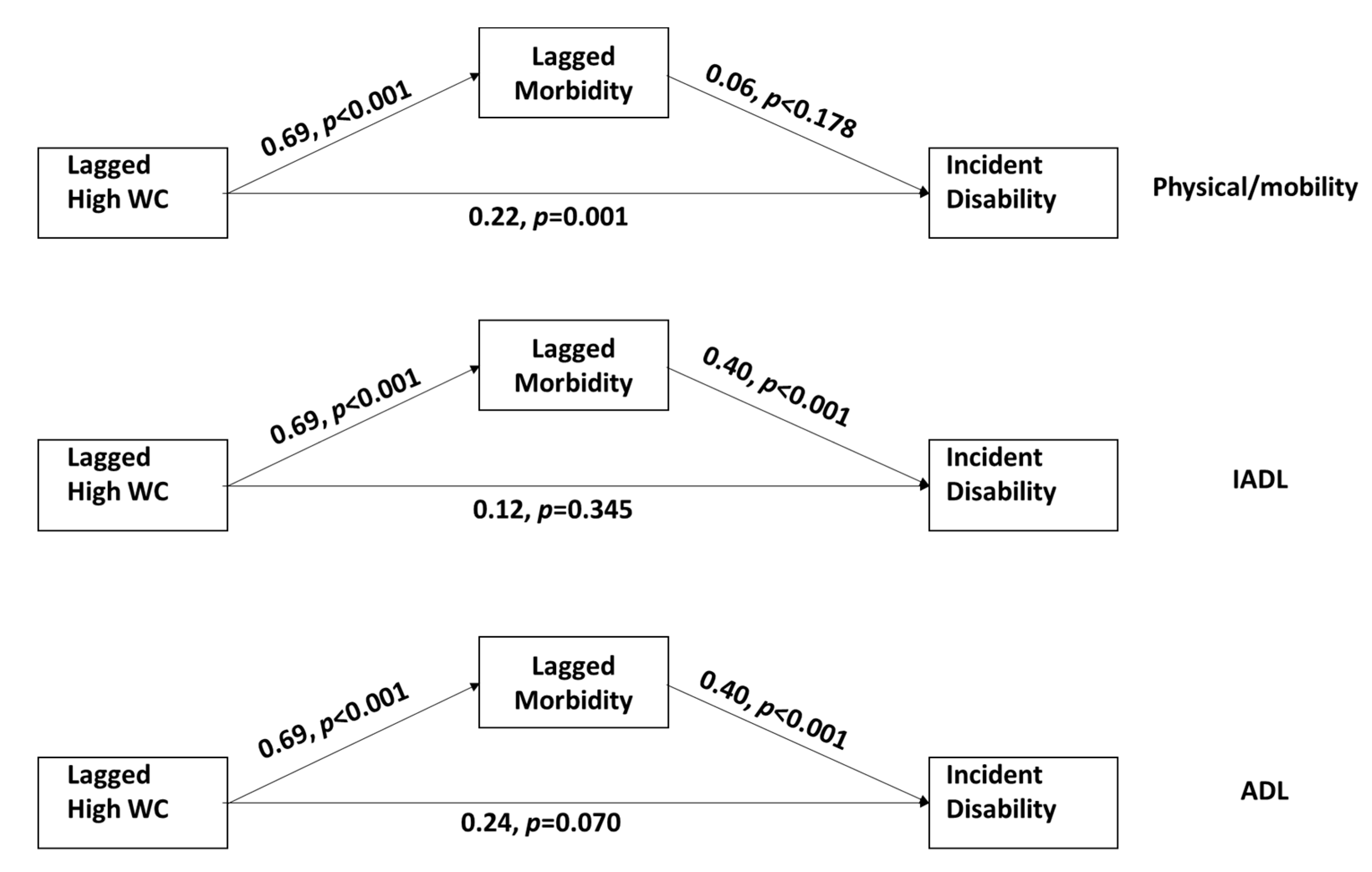

Our mediation analysis showed a significant direct effect of central obesity on incident physical/mobility limitations, even after accounting for the morbidity pathway. This suggests a direct physical effect of excess body weight on ability to perform these types of tasks, even in younger women.

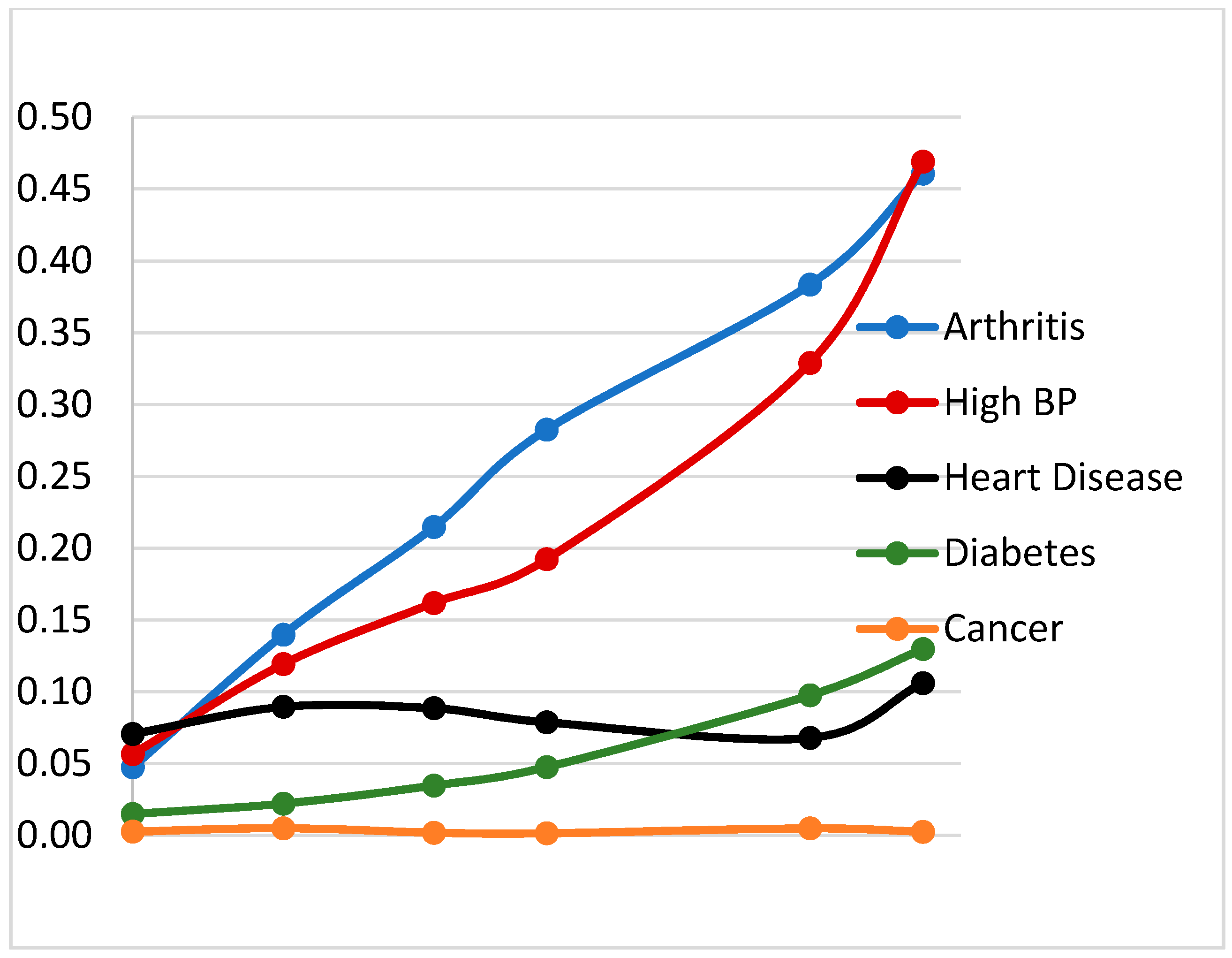

In contrast, lagged high WC was most strongly related to ADL and IADL limitations older women (those >60 at our last survey year). The mediation analysis showed that the influence of central obesity on these limitations is mostly indirect, operating through chronic disease morbidity. However, given the complexity of the ADL and IADL tasks, there may be other pathways related to upper limb function and dexterity not captured in our mediation models.

Central obesity is a well-known risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases [

26,

27] and our analysis both confirms this and shows the role of such diseases in incident ADL and IADL limitations. In addition, a study in China found waist circumference to be a better predictor than BMI among elderly in Beijing [

28]. Our observation that, without accounting for morbidity, central obesity relates to increased likelihood of ADL, IADL, or physical/mobility limitations is consistent with other studies that have explored obesity [

29]. In a cross sectional analysis of data from Guatemalan adults >50 years of age, Yount et al. [

24] found that overweight was not significantly associated with gross motor disability in women combined after adjustment for physician diagnosed illnesses.

We used two objective measures of physical function: timed up-and-go and grip strength. Women with overweight and obesity, particularly those who were older, had longer timed up-and-go. A study among Indian men and women in a similar age group found that timed up-and-go was not significantly associated with weight (r = 0.009) or BMI (r = 0.058) based on simple correlations [

30]. Among Cebu women, the simple correlations (r = 0.019 for weight and r = 0.044 for BMI) were similar to those in the India study [

30], but our analysis focused on more extreme values of BMI represented as overweight and obesity.

Among CLHNS participants, grip strength was strongly related to BMI, and women with overweight and obesity having higher grip strength. Based on estimates from bioelectric impedance analysis, the correlation of BMI with muscle mass in out CLHNS participants is 0.71. This may explain the observed positive association. In contrast, a study in South Africa [

31] found no association of grip strength with weight status and an Australian study found an inverse association of grip strength with BMI with grip strength in participants between 30 and 70 years of age [

32].

Most CLHNS participants are of low SES, and about 75–80% live in highly urban environments. Survey years covered a period of rapid economic change associated with the nutrition transition [

33] exemplified by rapid increases in overweight and obesity over the two decades covered in the current analysis. We found that living in a more urban environment was associated with increased incidence of all types of functional limitations. A higher level of urbanization in Cebu is associated with less occupational physical activity, and higher fat, lower quality diets, and these factors contribute to increased BMI and prevalence of overweight and obesity [

18]. Women living more traditional lives in rural areas appear to be more protected against these risks.

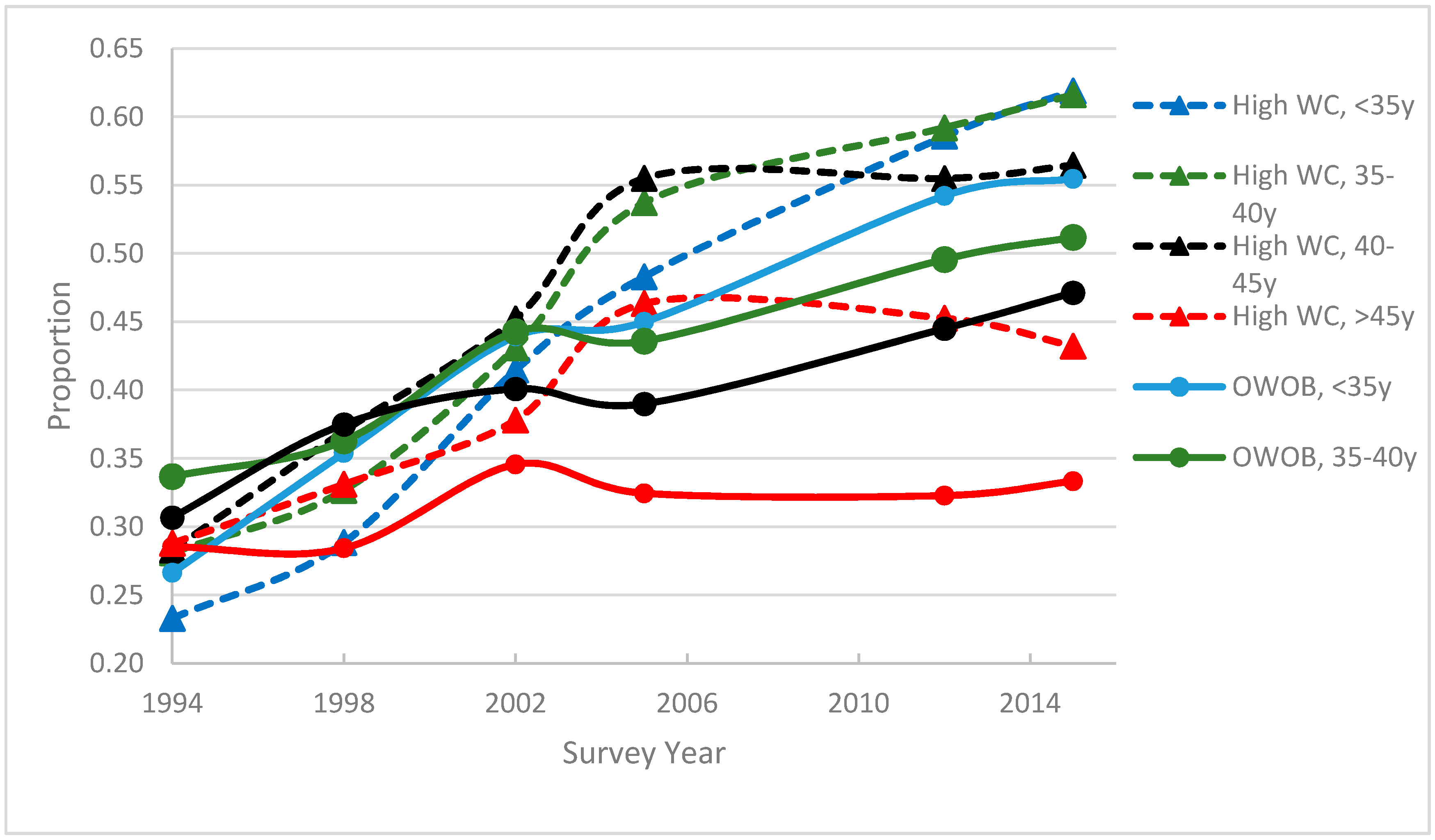

By 2015, about 60% of CLHNS participants across all ages had a WC > 80 cm, putting them at risk for functional limitations as well as cardiometabolic diseases. Increases in overweight and obesity and high WC were greatest among younger women, while rates leveled off over time in the oldest group. This suggests that the current generation of women who were still 45–60 years of age in 2015 could be facing rapidly increasing morbidity and functional limitations as they age. The lack of association of education, household income, and assets with incident disability suggests that obesity prevention efforts are needed across all SES groups.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used self-reported morbidity data. As this was not a clinical study, we do not have verified diagnoses of arthritis, heart disease, and cancer. Our measured blood pressure and HbA1c data suggest under-reporting of these conditions, likely because they are undiagnosed because of lack of regular screening. Thus, our morbidity score may not have fully captured true disease, and we may have underestimated the effects of morbidity on functional limitations in our mediation analysis. Second, the incidence of severe ADL limitations was quite low, particularly among groups representing high WC and age. Thus, we were not able to estimate that model. Third, as with any long-running cohort study, the CLHNS sample suffered considerable attrition over time. We noted that the retained sample generally had lower SES but lower morbidity and fewer functional limitations than women lost to follow-up. However, our use of inverse probability weighting suggested no attrition bias, meaning that the relationship of overweight, obesity, and high WC to functional limitations was not different in the retained sample and those lost to follow-up.