Cardiometabolic Index, BMI, Waist Circumference, and Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity Risk in Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Exposures, Covariates, and Outcome

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

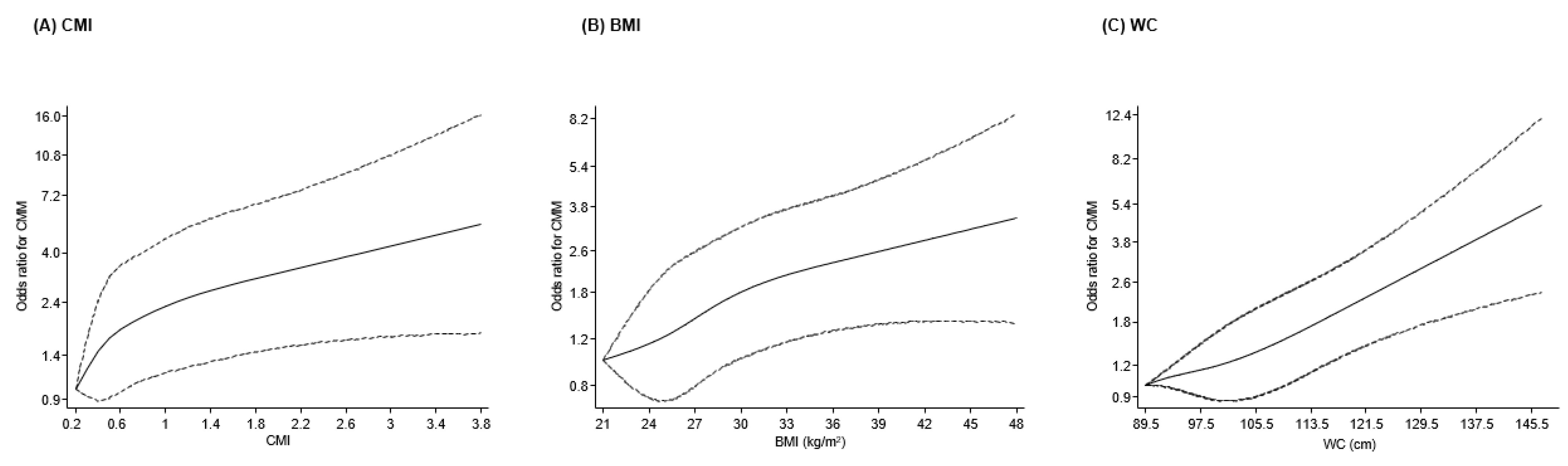

3.2. Associations of CMI, BMI, and WC with CMM

3.3. Risk Prediction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CMI | Cardiometabolic index |

| CMM | Cardiometabolic multimorbidity |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| ELSA | English Longitudinal Study of Ageing |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HGS | Handgrip strength |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| WC | Waist circumference |

References

- Eroglu, T.; Capone, F.; Schiattarella, G.G. The evolving landscape of cardiometabolic diseases. EBioMedicine 2024, 109, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen-Telders, C.; Schlaich, M.; Schutte, A.E.; Stergiou, G.; Poulter, N.R.; Beaney, T.; Investigators, M.M.M. Risk factors for cardiometabolic multimorbidity: An analysis of 4 million participants from May Measurement Month 2017–2019. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae666.2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parto, P.; Lavie, C.J. Obesity and Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2017, 42, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.; Guo, J.; Marseglia, A.; Fastbom, J.; Vetrano, D.L.; Fratiglioni, L.; Pedersen, N.L.; Xu, W. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity and incident dementia: The Swedish twin registry. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Franca, D.G.; Caruzzo, N.M.; Batista, S.R.R.; de Oliveira, C.; Nunes, B.P.; Silveira, E.A. Multimorbidity patterns and hospitalisation occurrence in adults and older adults aged 50 years or over. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Ambrosi, J.; Silva, C.; Galofre, J.C.; Escalada, J.; Santos, S.; Millan, D.; Vila, N.; Ibanez, P.; Gil, M.J.; Valenti, V.; et al. Body mass index classification misses subjects with increased cardiometabolic risk factors related to elevated adiposity. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevill, A.M.; Stewart, A.D.; Olds, T.; Holder, R. Relationship between adiposity and body size reveals limitations of BMI. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2006, 129, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Allison, D.B.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Kelley, D.E.; Leibel, R.L.; Nonas, C.; Kahn, R. Waist Circumference and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Consensus Statement from Shaping America’s Health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Obesity 2007, 15, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008; Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer, N.Y.; Krakauer, J.C. A new body shape index predicts mortality hazard independently of body mass index. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.M.; Bredlau, C.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Mueller, M.; Shen, W.; Gallagher, D.; Maeda, Y.; McDougall, A.; Peterson, C.M.; Ravussin, E.; et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity 2013, 21, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.C.; Giordano, C.; Galia, M.; Criscimanna, A.; Vitabile, S.; Midiri, M.; Galluzzo, A.; AlkaMeSy Study, G. Visceral Adiposity Index: A reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, N.H.; Kwon, T.Y.; Kim, S.G. A novel adiposity index as an integrated predictor of cardiometabolic disease morbidity and mortality. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, H.S. The “lipid accumulation product” performs better than the body mass index for recognizing cardiovascular risk: A population-based comparison. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2005, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcott, O.O.; Bergman, R.N. Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage horizontal line A cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R. A simple model-based index of abdominal adiposity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1991, 44, 955–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Jae, S.Y.; Dey, R.S.; Laukkanen, J.A. Comparative evaluation of relative fat mass and body mass index in predicting cardiometabolic multimorbidity in older adults: Results from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Geroscience 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.I.; Liu, C.S.; Lin, C.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Li, T.C.; Lin, C.C. Association of body indices and risk of mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2023, 11, e003474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Y. Weight-adjusted waist index as a practical predictor for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and non-accidental mortality risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 2498–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Jae, S.Y.; Laukkanen, J.A. A Paradoxical Association Between A Body Shape Index and Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Jae, S.Y.; Laukkanen, J.A. Association between weight-adjusted waist index and cardiometabolic multimorbidity in older adults: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Geroscience 2025, 47, 6429–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, I.; Daimon, T. The “cardiometabolic index” as a new marker determined by adiposity and blood lipids for discrimination of diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 438, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xu, J. Relationship Between Cardiometabolic Index and Insulin Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Jin, H.; Yin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Association of cardiometabolic index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged and elderly populations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Yi, Q.; Li, S.; Sun, W.; Ren, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xia, W.; Song, P. Transition of cardiometabolic status and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged and older Chinese: A national cohort study. J. Diabetes Investig. 2022, 13, 1426–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzer, S.; D’Alleva, M.; Isola, M.; De Martino, M.; Caroli, D.; Bondesan, A.; Marra, A.; Sartorio, A. Cardiometabolic Index (CMI) and Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) Highlight a Higher Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in Women with Severe Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.R.; Wang, H.Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, X.F.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.X. Estimate of prevalent diabetes from cardiometabolic index in general Chinese population: A community-based study. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Breeze, E.; Banks, J.; Nazroo, J. Cohort profile: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillari, L.; Frank, P.; Cadar, D. Systemic inflammation, lifestyle behaviours and dementia: A 10-year follow-up investigation. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 38, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chang, Z.; Song, C.; Cui, K.; Yuan, S.; Qiao, Z.; Bian, X.; Gao, Y.; Dou, K. Association of sleep quality, its change and sleep duration with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2023, 39, e3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounkpatin, H.; Islam, N.; Stuart, B.; Santer, M.; Farmer, A.; Dambha-Miller, H. The association of loneliness and social isolation with multimorbidity over 14 years in older adults in England: A population-based cohort study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 131, 105763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.B.; Zaninotto, P.; Steel, N.; Mindell, J. Undiagnosed diabetes-data from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Diabet. Med. 2009, 26, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Sun, S.; Tian, H.; Li, S.; Wu, Y. Sex Differences in the Associations of Handgrip Strength and Asymmetry With Multimorbidity: Evidence From the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 493–498.e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glymour, M.M.; Avendano, M. Can self-reported strokes be used to study stroke incidence and risk factors?: Evidence from the health and retirement study. Stroke 2009, 40, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Durrleman, S.; Simon, R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat. Med. 1989, 8, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajulu, U.S.; Spiegelman, D.; Thurston, S.W.; Ganguli, B.; Eisen, E.A. Comparing smoothing techniques in Cox models for exposure-response relationships. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 3735–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Laukkanen, J.A. Sleep duration and quality, physical activity and cardiometabolic multimorbidity: Findings from the English Longitudinal study of Ageing. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2025, 59, 2550279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation 2007, 115, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yin, Z.; Li, X.; Sheng, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, D.; Xue, Y. Cardiometabolic index predicts cardiovascular events in aging population: A machine learning-based risk prediction framework from a large-scale longitudinal study. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1551779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, L.; Lai, M.; Wan, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, R. Cardiometabolic index and the risk of new-onset chronic diseases: Results of a national prospective longitudinal study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1446276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarboo, A.; Fallahtafti, P.; Jalali, S.; Khanmohammadi, S.; Eslami, M.; Pourghazi, F.; Saadaeijahromi, H. The association between cardiometabolic index (CMI) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Xie, Y.; Gong, Y. Association between cardiometabolic index and cardiometabolic multimorbidity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: Evidence from a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.H.; Lim, J.P.; Lim, W.S.; Gao, F.; Teo, L.L.Y.; Ewe, S.H.; Keng, B.M.H.; Tan, R.S.; Koh, W.P.; Koh, A.S. Obesity in Older Adults and Associations with Cardiovascular Structure and Function. Obes. Facts 2022, 15, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Neeland, I.J.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; Cuevas, A.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streja, E.; Feingold, K.R. Evaluation and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in the Elderly. In Endotext [Internet]; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G.P., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. Updated 1 April 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279133/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Ponti, F.; Santoro, A.; Mercatelli, D.; Gasperini, C.; Conte, M.; Martucci, M.; Sangiorgi, L.; Franceschi, C.; Bazzocchi, A. Aging and Imaging Assessment of Body Composition: From Fat to Facts. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, J.A.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Yates, T.; Willeit, P.; Kujala, U.M.; Khan, H.; Zaccardi, F. Prognostic Relevance of Cardiorespiratory Fitness as Assessed by Submaximal Exercise Testing for All-Cause Mortality: A UK Biobank Prospective Study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, T.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Ma, X. Contribution of low skeletal muscle mass in predicting cardiovascular events: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 114, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2008, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Isiozor, N.M.; Khan, H.; Laukkanen, J.A. Handgrip strength-A risk indicator for type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2021, 37, e3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 3348) | No CMM (N = 3151) | Yes CMM (N = 197) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), Median (Q1–Q3), or n (%) | Mean (SD), Median (Q1–Q3), or n (%) | Mean (SD), Median (Q1–Q3), or n (%) | ||

| Cardiometabolic index | 0.70 (0.59) | 0.69 (0.57) | 0.95 (0.74) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.6 (4.9) | 27.4 (4.8) | 29.8 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 95.0 (13.3) | 94.6 (13.0) | 101.8 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 166.7 (9.5) | 166.6 (9.5) | 168.1 (9.6) | 0.028 |

| Weight, kg | 76.7 (15.6) | 76.2 (15.4) | 84.3 (18.1) | <0.001 |

| Age, yrs | 63.5 (8.5) | 63.5 (8.6) | 62.6 (6.5) | 0.13 |

| Sex | 0.10 | |||

| Male | 1510 (45.1%) | 1410 (44.7%) | 100 (50.8%) | |

| Female | 1838 (54.9%) | 1741 (55.3%) | 97 (49.2%) | |

| Current smoker | 0.034 | |||

| No | 2873 (85.8%) | 2714 (86.1%) | 159 (80.7%) | |

| Yes | 475 (14.2%) | 437 (13.9%) | 38 (19.3%) | |

| Alcohol categories | 0.85 | |||

| None | 1121 (33.5%) | 1051 (33.4%) | 70 (35.5%) | |

| 1–2 times/wk | 843 (25.2%) | 797 (25.3%) | 46 (23.4%) | |

| 3–4 times/wk | 636 (19.0%) | 601 (19.1%) | 35 (17.8%) | |

| 5 or more times/wk | 748 (22.3%) | 702 (22.3%) | 46 (23.4%) | |

| Handgrip strength, kg | 31.0 (11.4) | 30.9 (11.3) | 32.7 (11.9) | 0.028 |

| SBP, mmHg | 130 (17) | 130 (17) | 137 (17) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.84 (1.14) | 5.85 (1.13) | 5.59 (1.20) | 0.002 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.59 (0.42) | 1.60 (0.42) | 1.45 (0.41) | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.40 (1.00, 2.00) | 1.40 (1.00, 2.00) | 1.70 (1.20, 2.50) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity level | 0.18 | |||

| Physically inactive | 91 (2.7%) | 85 (2.7%) | 6 (3.0%) | |

| Low | 593 (17.7%) | 547 (17.4%) | 46 (23.4%) | |

| Moderate | 1810 (54.1%) | 1710 (54.3%) | 100 (50.8%) | |

| High | 854 (25.5%) | 809 (25.7%) | 45 (22.8%) |

| Exposure | Events/ Total | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Cardiometabolic index | |||||||

| Per 1 SD increase | 197/3348 | 1.36 (1.21–1.51) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.09–1.45) | 0.002 | 1.25 (1.08–1.44) | 0.003 |

| Tertile 1 (0.06–0.37) | 37/1116 | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Tertile 2 (0.38–0.72) | 63/1116 | 1.75 (1.15–2.66) | 0.009 | 1.44 (0.90–2.29) | 0.13 | 1.40 (0.88–2.24) | 0.16 |

| Tertile 3 (0.73–6.40) | 97/1116 | 2.75 (1.85–4.09) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.15–3.41) | 0.013 | 1.88 (1.09–3.25) | 0.023 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||||||

| Per 1 SD increase | 197/3348 | 1.47 (1.30–1.66) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.14–1.49) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.12–1.47) | <0.001 |

| Tertile 1 (15.1–25.2) | 39/1125 | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Tertile 2 (25.3–28.8) | 60/1135 | 1.51 (0.99–2.28) | 0.053 | 1.31 (0.85–2.01) | 0.22 | 1.30 (0.85–2.00) | 0.23 |

| Tertile 3 (≥28.9) | 98/1088 | 2.69 (1.84–3.94) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.29–2.95) | 0.001 | 1.88 (1.24–2.85) | 0.003 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||||||

| Per 1 SD increase | 197/3348 | 1.69 (1.47–1.94) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.28–1.73) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.25–1.71) | <0.001 |

| Tertile 1 (60.5–88.8) | 33/1122 | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Tertile 2 (88.9–100.3) | 69/1119 | 2.31 (1.49–3.59) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.24–3.04) | 0.004 | 1.91 (1.22–2.99) | 0.005 |

| Tertile 3 (≥100.4) | 95/1107 | 3.36 (2.17–5.18) | <0.001 | 2.27 (1.43–3.60) | 0.001 | 2.16 (1.35–3.44) | 0.001 |

| Measure of Discrimination | CMI | BMI | WC |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-index (95% CI): established risk factors | 0.6892 (0.6500, 0.7285) | 0.6892 (0.6500, 0.7285) | 0.6892 (0.6500, 0.7285) |

| C-index (95% CI): established risk factors plus exposure | 0.6924 (0.6528, 0.7319) | 0.6941 (0.6551, 0.7331) | 0.6992 (0.6603, 0.7382) |

| C-index change (p-value) | 0.0032 (0.55) | 0.0049 (0.46) | 0.0100 (0.24) |

| p-value for difference in −2 log likelihood | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kunutsor, S.K.; Laukkanen, J.A. Cardiometabolic Index, BMI, Waist Circumference, and Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity Risk in Older Adults. Geriatrics 2026, 11, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010004

Kunutsor SK, Laukkanen JA. Cardiometabolic Index, BMI, Waist Circumference, and Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity Risk in Older Adults. Geriatrics. 2026; 11(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleKunutsor, Setor K., and Jari A. Laukkanen. 2026. "Cardiometabolic Index, BMI, Waist Circumference, and Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity Risk in Older Adults" Geriatrics 11, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010004

APA StyleKunutsor, S. K., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2026). Cardiometabolic Index, BMI, Waist Circumference, and Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity Risk in Older Adults. Geriatrics, 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010004