Cooled Radiofrequency at Five Revised Targets for Short-Term Pain and Physical Performance Improvement in Elderly Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Four-Case Reports

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Concerns

2.2. Participants

2.3. Therapeutic Intervention

2.4. Data Monitoring

3. Study Cases Presentation

4. Discussion

5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A-P | anterior–posterior |

| CRF | cooled radiofrequency |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| RF | radiofrequency |

| SUS | Brazil’s Unified Health System |

| UNIFAL-MG | Federal University of Alfenas |

| USD | American dollar |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| YLDs | Years lived with disability |

References

- Brandt, K.D.; Radin, E.L.; Dieppe, P.A.; van de Putte, L. Yet more evidence that osteoarthritis is not a cartilage disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006, 65, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Robbins, S.R.; McDougall, J.J. Osteoarthritis: The genesis of pain. Rheumatology 2018, 57, iv43–iv50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, I.B.; Plapler, P.G.; de Campos, G.C. Generating evidence and understanding the treatment of osteoarthritis in Brazil: A study through Delphi methodology. Clinics 2019, 74, e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, G.M.; Tol, A.W.; Bergink, A.P.; Belo, J.N.; Bernsen, R.M.D.; Reijman, M.; Pols, H.A.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driban, J.B.; Hootman, J.M.; Sitler, M.R.; Harris, K.P.; Cattano, N.M. Is Participation in Certain Sports Associated With Knee Osteoarthritis? A Systematic Review. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, A.M.; Li, L.C. Occupational Physical Loading Tasks and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review of the Evidence. Physiother. Can. 2014, 66, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øiestad, B.E.; Juhl, C.B.; Eitzen, I.; Thorlund, J.B. Knee extensor muscle weakness is a risk factor for development of knee osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runhaar, J.; van Middelkoop, M.; Reijman, M.; Vroegindeweij, D.; Oei, E.H.G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. Malalignment: A possible target for prevention of incident knee osteoarthritis in overweight and obese women. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 1618–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1745–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.; De Santis, V.; Tafuro, L. Reliability of the Ahlbäck classification of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2003, 11, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Kendzerska, T.; Stanaitis, I.; Hawker, G. The relationship between knee pain characteristics and symptom state acceptability in people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlone, A.G.; Grothaus, O.; Jacobs, C.; Duncan, S.T. Is Cooled Radiofrequency Genicular Nerve Block and Ablation a Viable Option for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis? Arthroplast. Today 2021, 7, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, F.M. Cooled Radiofrequency Genicular Neurotomy. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 23, 100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.J.; Hwang, S.J.; Song, J.G.; Leem, J.G.; Kang, Y.U.; Park, P.H.; Shin, J.W. Radiofrequency treatment relieves chronic knee osteoarthritis pain: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Pain 2011, 152, 1933–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.; Loudermilk, E.; DePalma, M.; Hunter, C.; Lindley, D.; Patel, N.; Choi, D.; Soloman, M.; Gupta, A.; Desai, M.; et al. Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized, Crossover Clinical Trial Comparing the Safety and Effectiveness of Cooled Radiofrequency Ablation With Corticosteroid Injection in the Management of Knee Pain From Osteoarthritis. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2018, 43, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyman, J.; Khalouf, F.; Zora, K.; DePalma, M.; Loudermilk, E.; Guiguis, M.; Beall, D.; Kohan, L.; Chen, A.F. Cooled radiofrequency ablation of genicular nerves provides 24-Month durability in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain: Outcomes from a prospective, multicenter, randomized trial. Pain Pract. 2022, 22, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhi, A.J.; Hamal, P.K.; Yadav, R.K.; Pokhrel, N.; Paudel, P.; Paudel, S.C.; Dhungel, B.K. Clinical Outcome of Cooled Radiofrequency Ablation in Chronic Knee Pain Osteoarthritis: An Initial Experience from Nepal. J. Nepal. Health Res. Counc. 2021, 19, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkoue, L.; Behets, C.W.; Steyaert, A.; Kouassi, J.E.K.; Detrembleur, C.; De Waroux, B.L.P.; Cornu, O. Accuracy of fluoroscopic-guided genicular nerve blockade: A need for revisiting anatomical landmarks. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 44, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkoué, L.; Behets, C.; Kouassi, J.É.K.; Coyette, M.; Detrembleur, C.; Thienpont, E.; Cornu, O. Distribution of sensory nerves supplying the knee joint capsule and implications for genicular blockade and radiofrequency ablation: An anatomical study. Sur. Radiol. Anat. 2019, 41, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkoue, L.; Behets, C.W.; Steyaert, A.; Kouassi, J.E.K.; Detrembleur, C.; De Waroux, B.L.; Cornu, O. Current versus revised anatomical targets for genicular nerve blockade and radiofrequency ablation: Evidence from a cadaveric model. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 45, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonkoue, L.; Behets, C.W.; Steyaert, A.; Kouassi, J.E.K.; Detrembleur, C.; Cornu, O. Anatomical evidence supporting the revision of classical landmarks for genicular nerve ablation. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 45, 672–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, J.; Peng, P.W.H.; Lam, K.; Baig, E.; Agur, A.M.R.; Gofeld, M. Anatomical Study of the Innervation of Anterior Knee Joint Capsule. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2018, 43, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkoue, L.; Steyaert, A.; Kouame, J.E.K.; Bandolo, E.; Lebleu, J.; Fossoh, H.; Behets, C.; Detrembleur, C.; Cornu, O. A Comparison of Genicular Nerve Blockade With Corticosteroids Using Either Classical Anatomical Targets vs Revised Targets for Pain and Function in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.M.; González, D.A. Radiofrequency of genicular nerves to relieve osteoarthritis knee pain. MOJ Orthop. Rheumatol. 2019, 11, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Liu, B.; Sima, L. Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation for chronic osteoarthritis knee pain in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Physician 2024, 27, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, F. The Aging Population in Brazil. 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26539997_The_aging_population_in_Brazil (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Travassos, G.F.; Coelho, A.B.; Arends-Kuenning, M.P. The elderly in Brazil: Demographic transition, profile, and socioeconomic condition. Rev. Bras. De Estud. De Popul. 2020, 37, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil (Ministry of Health). Protocol for Safe Surgery. 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/centraisdeconteudo/publicacoes/servicosdesaude/publicacoes/protocolo-de-cirurgia-segura (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Simons, D.G.; Travell, J.G.; Simons, L.S. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, 2nd ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, F.C.K.; West, D.W.D.; Linde, L.D.; Hassan, S.; Kumbhare, D.A. Re-examining myofascial pain syndrome: Toward biomarker development and mechanism-based diagnostic criteria. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasuo, H.; Ishiki, H.; Matsuoka, H.; Fukunaga, M. Clinical characteristics of myofascial pain syndrome with psychological stress in patients with cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, T.; Allen, C.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, A.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1545–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifer, V.P.; Katz, J.N.; Losina, E. The burden of OA-health services and economics. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacca, D.M.; De-Campos, G.C.; Zorzi, A.R.; Chaim, E.A.; De-Miranda, J.B. Prevalence of joint pain and osteoarthritis in obese brazilian population. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2018, 31, e1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, M.R.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C.A. The evolving role of obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2010, 22, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Blas, J.A.; Castañeda, S.; Largo, R.; Herrero-Beaumont, G. Osteoarthritis associated with estrogen deficiency. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellgren, J.H.; Lawrence, J.S. Radiological Assessment of Osteo-Arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mündermann, A.; Dyrby, C.O.; Andriacchi, T.P. Secondary gait changes in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: Increased load at the ankle, knee, and hip during walking. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2835–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Cui, R.; Zhang, X. The Link between Depression and Chronic Pain: Neural Mechanisms in the Brain. Neural Plast. 2017, 2017, 9724371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corallo, F.P.; De Salvo, S.; Floridia, D.; Bonanno, L.; Muscarà, N.; Cerra, F.; Cannistraci, C.; Di Cara, M.; Buono, V.L.; Bramanti, P.; et al. Assessment of spinal cord stimulation and radiofrequency: Chronic pain and psychological impact. Medicine 2020, 99, e18633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Anastopoulou, G.G.; Bruna, J. Inconclusive evidence to support the use of minimally-invasive radiofrequency denervation against chronic low back pain. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, A.V.; Shilova, L.N.; Aleksandrova, N.V.; Alekhina, I.Y.; Aleksandrova, N.P. Ab0289 depression and metabolic disorders prevent remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 1270–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G.R.; Bernardo, A.F.B.; Faria, A.L.B.M.; Vanderlei, F.M.; Masseli, M.R.; Vanderlei, L.C.M. Automedicação em indivíduos com osteoartrose atendidos em uma unidade básica de saúde. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Saúde 2015, 19, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.M.F.N.; Silveira, M.R.; Acurcio, F.D.A.; Guerra Junior, A.A.; Guibu, I.A.; Costa, K.S.; Karnikowski, M.G.D.O.; Soeiro, O.M.; Leite, S.N.; Costa, E.A.; et al. Use of medicines by patients of the primary health care of the Brazilian Unified Health System. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 18s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Netto, I.F.; De Sousa, L.C.A.; Ferreira, B.R.; Tassara, K.R.; Silva, I.C.; Wastowski, I.J. O papel do farmacêutico na automedicação da “farmácia” caseira. Rev. Foco 2023, 16, e1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveza, L.A. UpToDate. Overview of the Management of Osteoarthritis. 2024. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-management-of-osteoarthritis (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Medication Without Harm. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- UN Brazil. About Our Work to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in Brazil. 2025. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/sdgs (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Karm, M.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.W.; Choi, S.S. Cooled radiofrequency ablation of genicular nerves for knee osteoarthritis. Korean J. Pain 2024, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.D.; Gonçalves, M.C.K.; Grando, S.T.; Grando, S.; de Lima Cintra, T.L.; Pinto, D.M.; Gonçalves, R.K. Indicações da neurotomia dos nervos geniculares por radiofrequência para o tratamento da osteoartrite do joelho: Uma revisão de literatura. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2019, 54, 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Oladeji, L.; Cook, J. Cooled Radio Frequency Ablation for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis-Related Knee Pain: Evidence, Indications, and Outcomes. J. Knee Surg. 2019, 32, 065–071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshi, E.; Meiling, J.B.; Conger, A.M.; McCormick, Z.L.; Burnham, T.R. Long-term clinical outcomes of genicular nerve radiofrequency ablation for chronic knee pain using a three-tined electrode for expanded nerve capture. Interv. Pain Med. 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kose, S.G.; Kose, H.C.; Celikel, F.; Akkaya, O. Predictive factors associated with successful response to utrasound guided genicular radiofrequency ablation. Korean J. Pain 2022, 35, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, M.S. Mechanisms of Myofascial Pain. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, 523924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Bajaj, P.; Graven-Nielsen, T.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Trigger Points in Patients with Lower Limb Osteoarthritis. J. Musculoskelet. Pain 2001, 9, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.; Cahill, C.M.; Wood, G.; Hroch, J.; Wilson, R.; Cupido, T.; VanDenKerkhof, E. Myofascial Pain in Patients Waitlisted for Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain Res. Manag. 2012, 17, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Age (Year) | Gender | Comorbidity | Knee of Procedure | Functional Status Before CRF | Functional Status After CRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 64 | Male | None | Left | Moderate to significant limitation | Good functional performance |

| B | 84 | Female | None | Left | Significant limitation | Significant functional limitation, limited improvement |

| C | 72 | Female | Depression | Right | Severe limitation | Moderate to significant limitation, with joint improvement, but still significant impact on mobility |

| D | 75 | Female | Depression, Metabolic disorder (diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia) | Right | Severe limitation | Good articulation, but functional limitation |

| Patient | VAS (Before) | Interpretation (Before) | VAS (After) | Interpretation (Before) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 10 | Worst pain possible | 1 | Mild pain |

| B | 10 | Worst pain possible | 10 | Worst pain possible |

| C | 10 | Worst pain possible | 7 | Very severe pain |

| D | 5 | Moderate pain | 1 | Mild pain |

| Patient | TUG Before CRF | TUG After CRF |

|---|---|---|

| A | 21.6 s | 13.2 s |

| B | 22.5 s | 22.0 s |

| C | 26.3 s | 23.4 s |

| D | 27.6 s | 22.4 s |

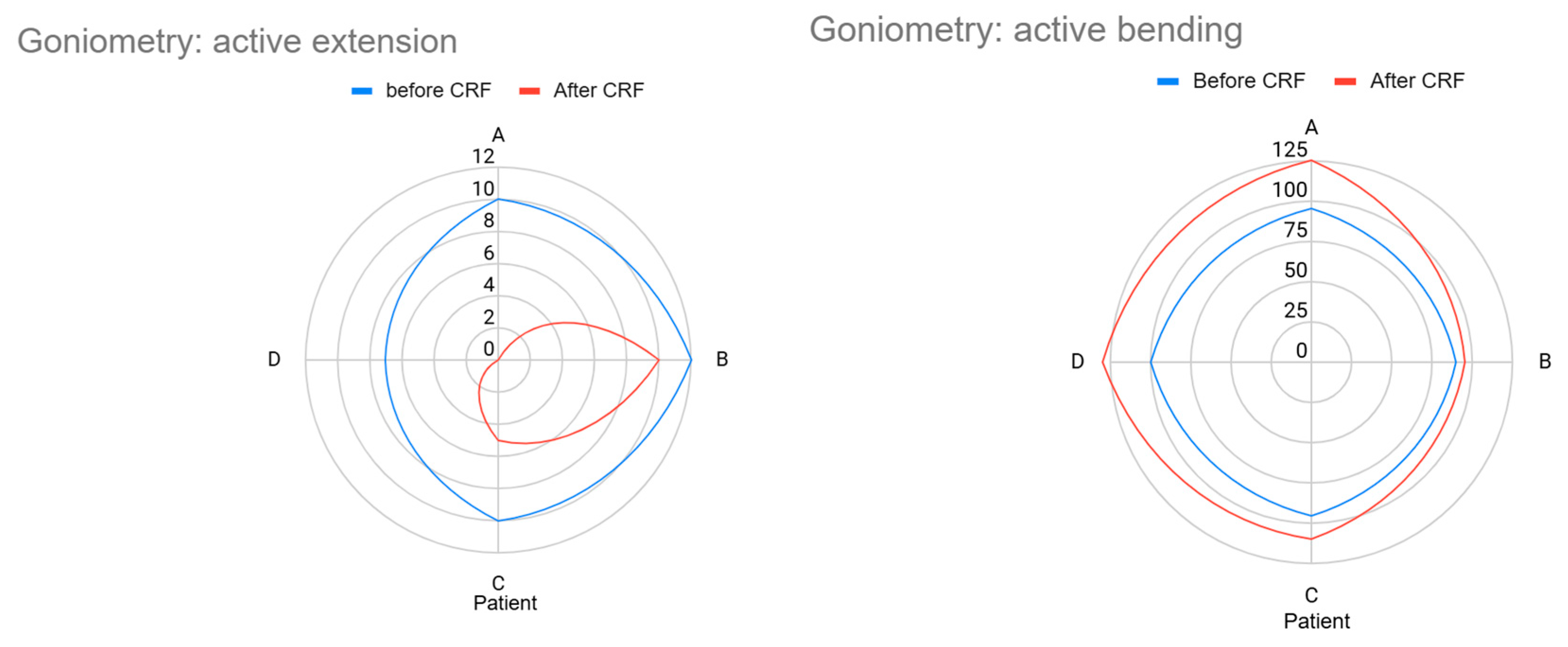

| Patient | Goniometry | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before CRF | After CRF | |||

| Active Extension | Active Bending | Active Extension | Active Bending | |

| A | 10° (flexion) | 95° | 0° | 125° |

| B | 12° (flexion) | 90° | 10° (holds flexion) | 95° |

| C | 10° (flexion) | 95° | 5° (still limited) | 110° |

| D | 7° (light flexion) | 100° | 0° | 130° |

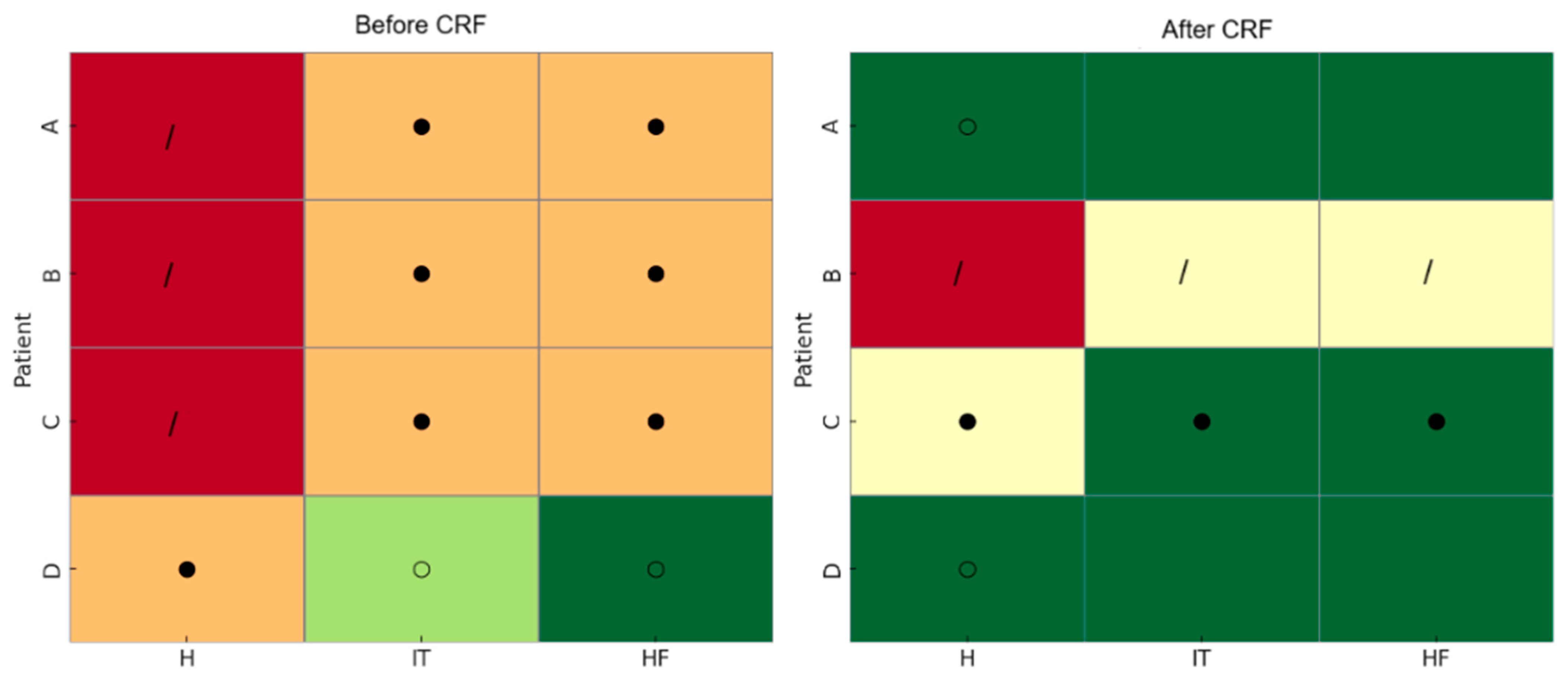

| Patient | Before CRF | After CRF | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palpated Muscles | ||||||||

| Q | IT | MG | H | Q | IT | MG | H | |

| A | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| B | * | - | - | - | *** | ** | *° | * |

| C | * | - | - | * | ** | * | - | * |

| D | */ | - | - | * | - | - | - | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, R.F.; de Barros, C.M.; Lima, A.A.V.; Vilela, F.T.; Boralli, V.B. Cooled Radiofrequency at Five Revised Targets for Short-Term Pain and Physical Performance Improvement in Elderly Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Four-Case Reports. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060170

Rodrigues RF, de Barros CM, Lima AAV, Vilela FT, Boralli VB. Cooled Radiofrequency at Five Revised Targets for Short-Term Pain and Physical Performance Improvement in Elderly Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Four-Case Reports. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(6):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060170

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Rafaela F., Carlos Marcelo de Barros, André A. V. Lima, Felipe T. Vilela, and Vanessa B. Boralli. 2025. "Cooled Radiofrequency at Five Revised Targets for Short-Term Pain and Physical Performance Improvement in Elderly Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Four-Case Reports" Geriatrics 10, no. 6: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060170

APA StyleRodrigues, R. F., de Barros, C. M., Lima, A. A. V., Vilela, F. T., & Boralli, V. B. (2025). Cooled Radiofrequency at Five Revised Targets for Short-Term Pain and Physical Performance Improvement in Elderly Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Four-Case Reports. Geriatrics, 10(6), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060170