Pet Ownership, Pet Attachment, and Longitudinal Changes in Psychological Health—Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Pet Ownership and Psychological Health

1.2. Pet Attachment and Psychological Health

1.3. Dog Walking and Psychological Health

1.4. Aims

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Participants

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Psychological Health Outcomes with Aging

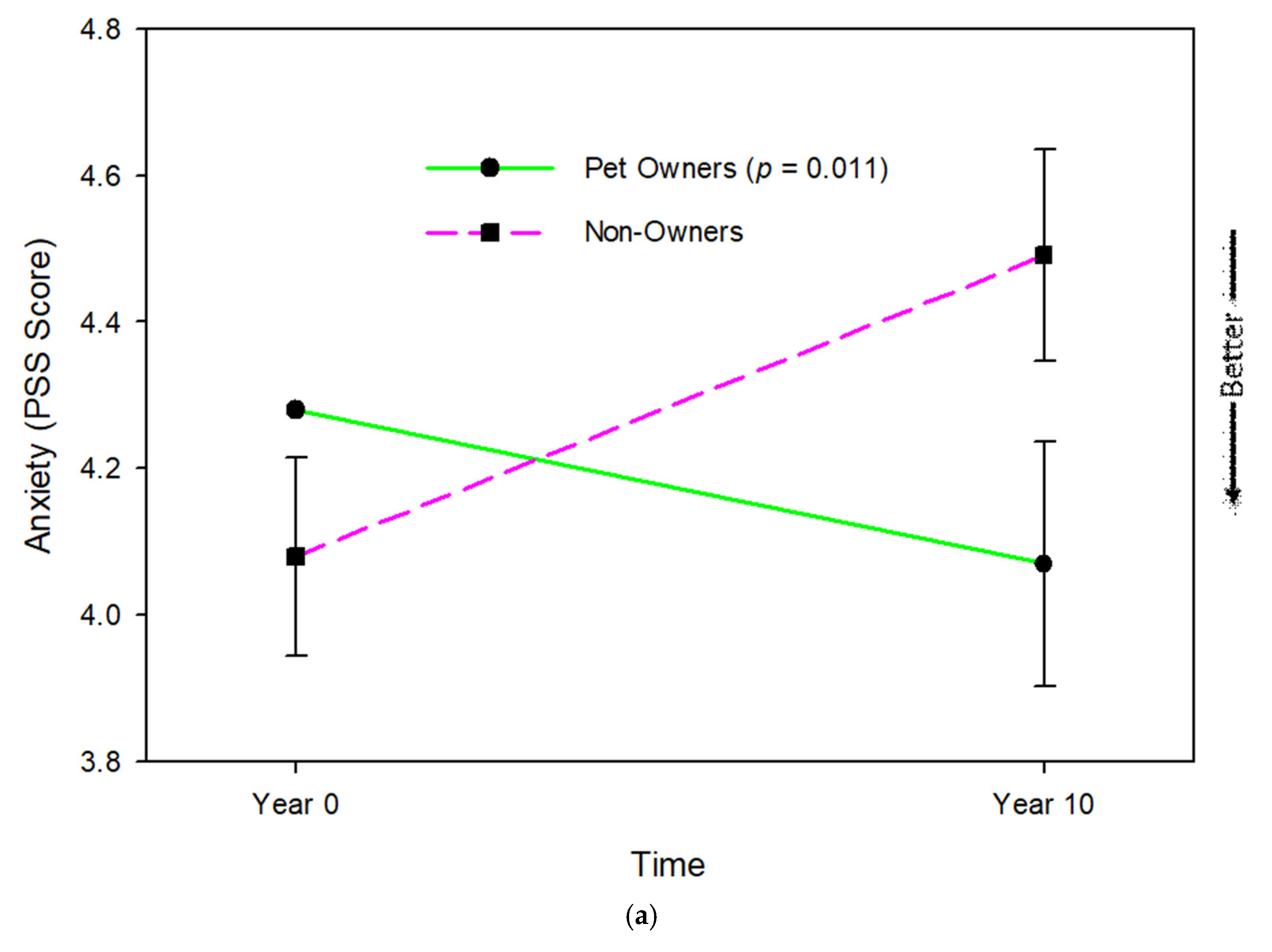

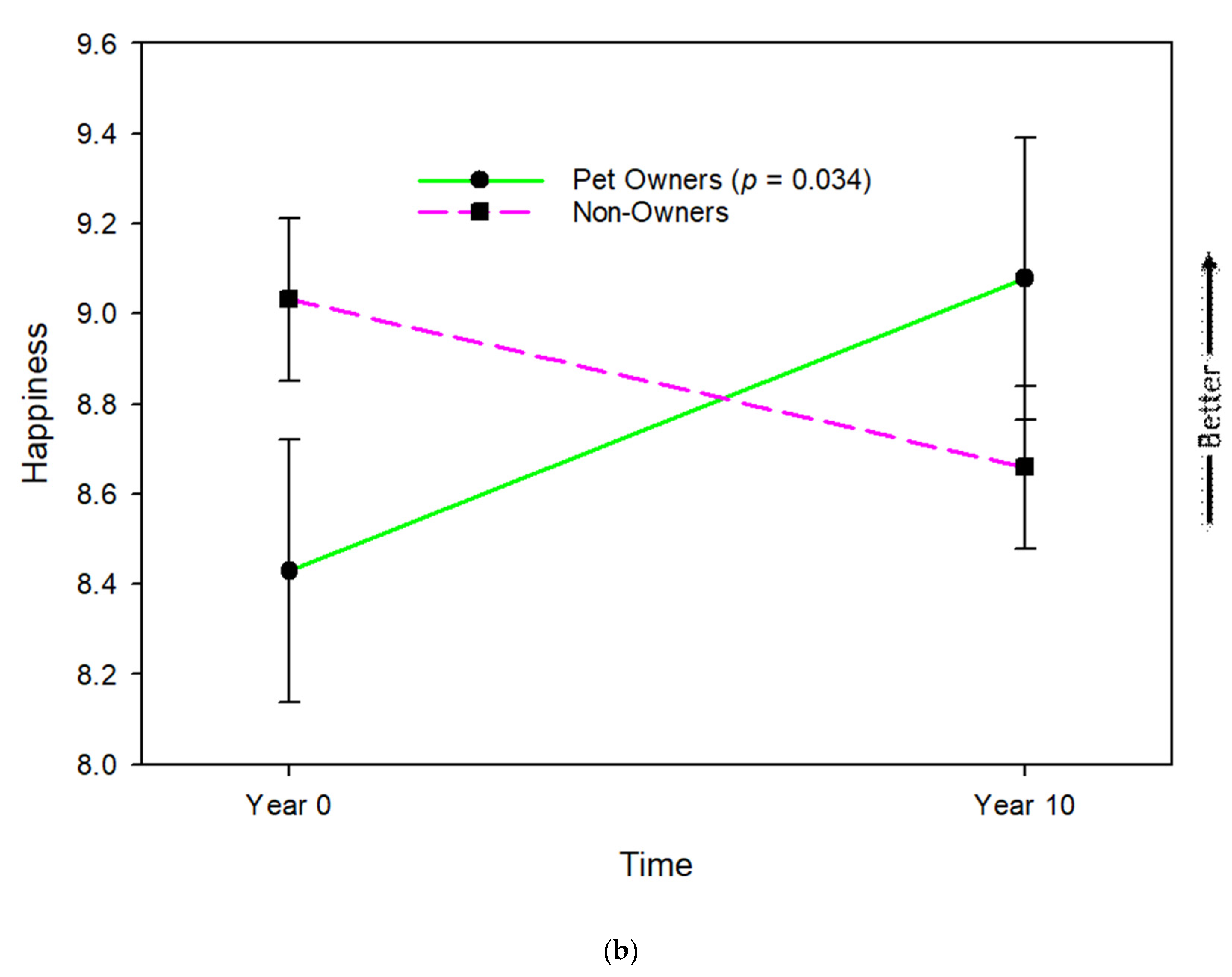

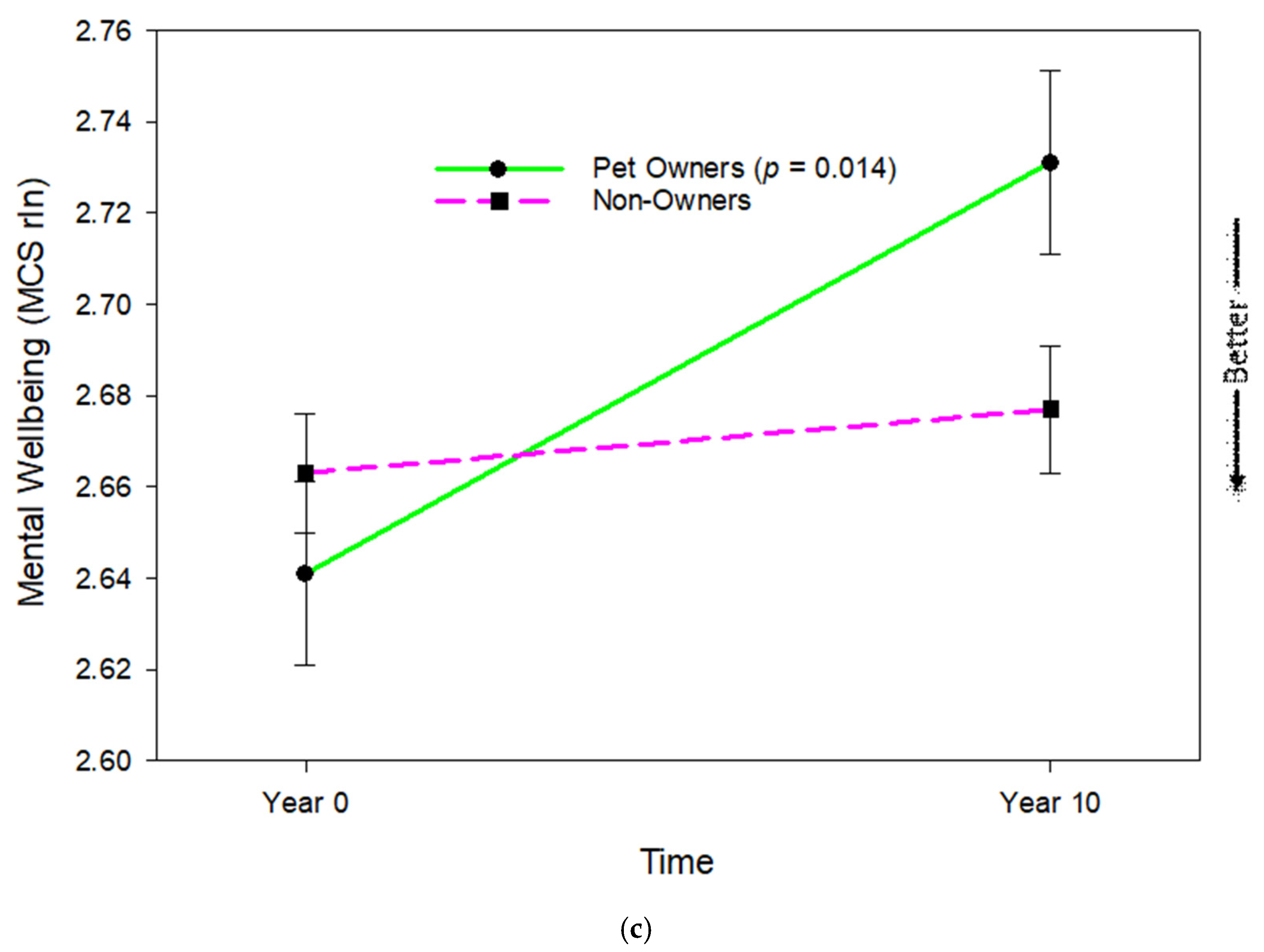

3.2. Moderation of Changes in Psychological Health by Pet Ownership

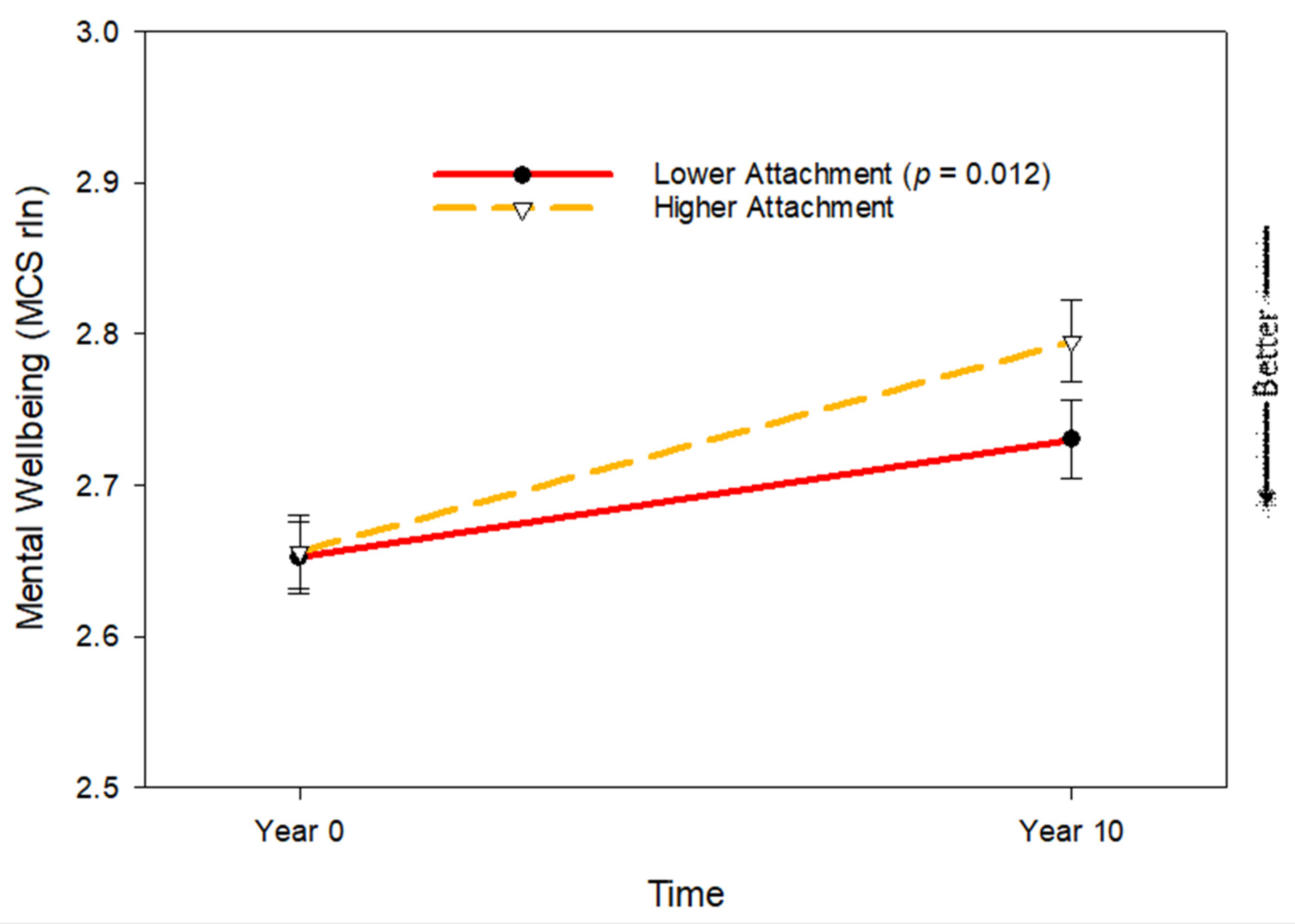

3.3. Pet Attachment and Changes in Pet Owners’ Psychological Health with Aging

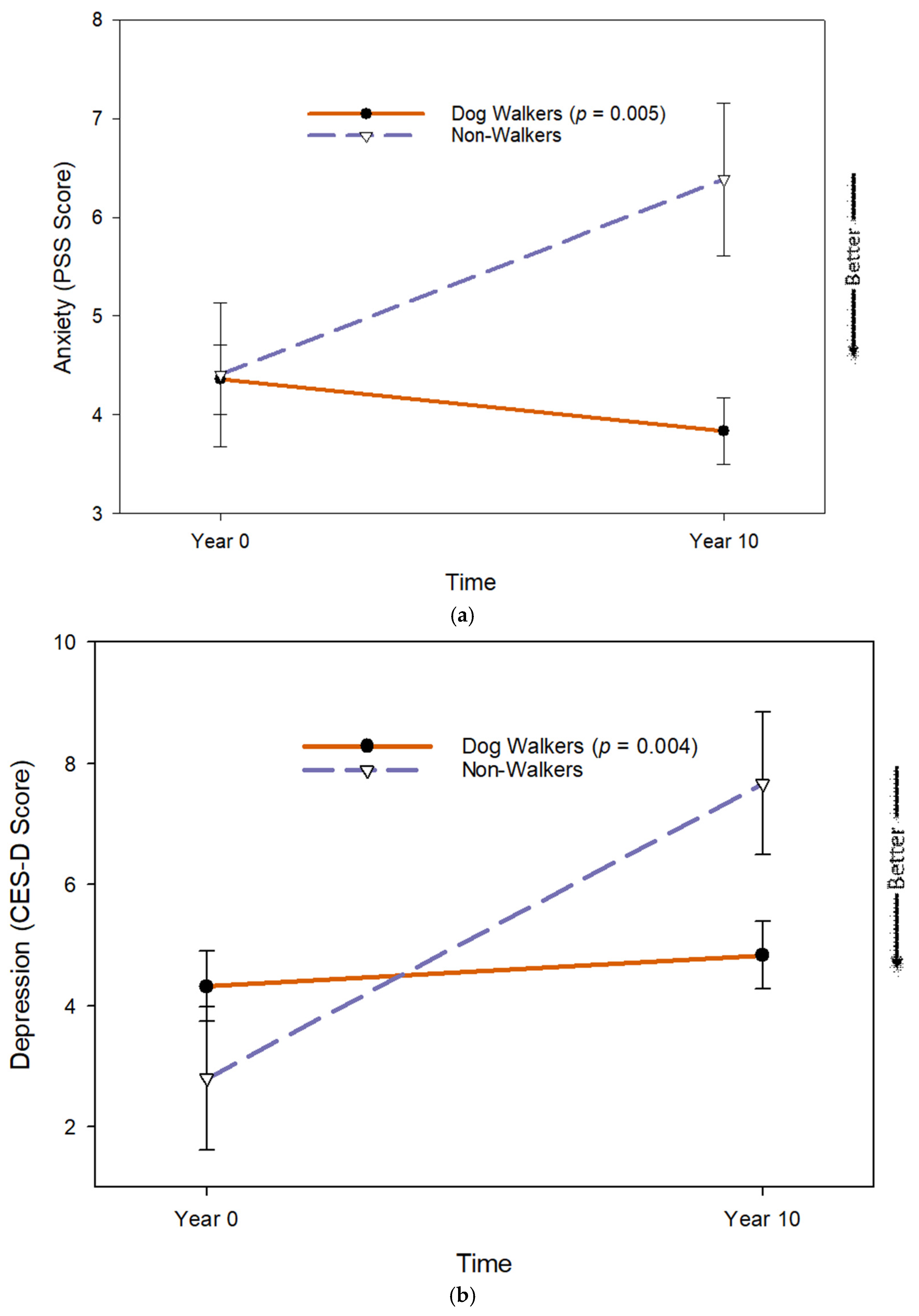

3.4. Dog Walking and Changes in Dog Owners’ Psychological Health with Aging

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vespa, J. The Greying of America: More Older Adults than Kids by 2035. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/03/graying-america.html (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Harmell, A.L.; Jeste, D.; Depp, C. Strategies for successful aging: A research update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, G.L. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. J. Med. Philos. 1981, 6, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albright, A.E.; Cui, R.; Allen, R.S. Pet ownership and mental and physical health in older White and Black males and females. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 5655. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, E. The Animal-human bond: Health and wellness. In Handbook on Animal Assisted Therapy, Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice; Fine, A.H., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Simonsick, E.M.; Barr, E.; Resnick, B.; Werthman, E.; Adesanya, I. Pet ownership and maintenance of physical function in older adults–Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). Innov. Aging 2023, 7, igac080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kitner-Triolo, M.H.; Resnick, B.; Adesanya, I.; Koodaly, L.; Gurlu, M. Pet ownership and maintenance of cognitive function in community-residing older adults: Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kitner-Triolo, M.H.; Resnick, B.; Gurlu, M.; Shim, S.; Adesanya, I. Pet attachment and maintenance of physical and cognitive function in community-residing older adults: Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). Anthrozoös 2025, 38, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2: Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2016. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-2.1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bolstad, C.J.; Porter, B.; Brown, C.J.; Kennedy, R.E.; Nadorff, M.R. The relation between pet ownership, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in late life: Propensity score matched analyses. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.C.; Trigg, J.L.; Godber, T.; Brown, C. An experience sampling approach to investigating associations between pet presence and indicators of psychological wellbeing and mood in older Australians. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parslow, R.A.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Jacomb, P. Pet ownership and health in older adults: Findings from a survey of 2,551 community-based Australians aged 60–64. Gerontology 2005, 51, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Shykoff, B.E.; Izzo, J.L., Jr. Pet ownership, but not ACE inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension 2001, 38, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L.F.; Marx, M.B.; Johnson, T.P. Pet ownership and attachment as supportive factors in the health of the elderly. Anthrozoös 1989, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, S.M.; Boss, L.; Padhye, N.S.; Gee, N.R.; Trötscher, T.T. Biopsychosocial factors and cognitive function in cat ownership and attachment in community-dwelling older adults. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.K.; Gee, N.R.; Bures, R.M. Human-animal interaction as a social determinant of health: Descriptive findings from the health and retirement study. BMC Public. Health 2018, 18, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branson, S.; Boss, L.; Cron, S.; Kang, D.-H. Examining differences between homebound older adult pet owners and non-pet owners in depression, systemic inflammation, and executive function. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, C.; Veronese, N.; Smith, L.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; Bitsika, V.; Demurtas, J.; Celotto, S.; Noventa, V.; Soysal, P.; Isik, A.T.; et al. Pet ownership and symptoms of depression: A prospective study of older adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, K.J.; Schreer, G. Pets and Happiness: Examining the Association between Pet Ownership and Wellbeing. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.T.G.; Hernández, R.L. Benefits of dog ownership: Comparative study of equivalent samples. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Simonsick, E.M.; Studenski, S.; Resnick, B.; Barr, E.; Kitner-Triolo, M.; Hackney, A. Pet ownership patterns and successful aging outcomes in community dwelling older adults. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Chi, L.K.; Luo, J. The effect of pets on happiness: A large-scale multi-factor analysis using social multimedia. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkljačić, T.; Sučić, I.; Lučić, L.; Tkalić, R.G.; Lipovčan, L.K. The Beginning, the End, and All the Happiness in Between: Pet Owners’ Wellbeing from Pet Acquisition to Death. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.T.; Thomas, S.J. Psychological mechanisms predicting wellbeing in pet owners: Rogers’ core conditions versus Bowlby’s attachment. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajfoner, D.; Ke, G.N.; Wong, R.M.M. The effect of pets on human mental health and wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia. Animals 2021, 11, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, J. Examining the role of pets in cancer survivors’ physical and mental wellbeing. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2022, 40, 834–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, M.; Eshuis, J.; Peeters, S.; Lataster, J.; Reijnders, J.; Enders-Slegers, M.-J.; Jacobs, N. The pet-effect in daily life: An experience sampling study on emotional wellbeing in pet owners. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, C.A. The mediating effect of pet attachment support between loneliness and general health in older females living in the community. J. Community Health Nurs. 2008, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. In Attachment Across the Life Cycle; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.; Stanton, S.C.E.; Hawkins, R.D.; Loughnan, S. The link between the nature of the human–companion animal relationship and well-being outcomes in companion animal owners. Animals 2024, 14, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, J.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Winefield, H. Mental health implications of human attachment to companion animals. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 68, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltiades, H.; Shearer, J. Attachment to pet dogs and depression in rural older adults. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, C.A. Pet ownership and older women: The relationships among loneliness, pet attachment support, human social support, and depressed mood. Geriatr. Nurs. 2012, 33, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winefield, H.R.; Black, A.; Chur-Hansen, A. Health effects of ownership of and attachment to companion animals in an older population. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budge, R.C.; Spicer, J.; Jones, B.; St. George, R. Health correlates of compatibility and attachment in human-companion animal relationships. Soc. Anim. 1998, 6, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Lloyd, E.P.; Humphrey, B.T. We are family: Viewing pets as family members improves wellbeing. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, R.M.; Reynolds, C.F. Management of depression in older adults: A review. JAMA 2017, 317, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J.L.-T.; Sotos, J.R. Effectiveness of physical exercise in older adults with mild to moderate depression. Ann. Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragina, I.; Voelcker-Rehage, C. The exercise effect on psychological well-being in older adults—A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2018, 48, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. The facilitation of social interactions by domestic dogs. Anthrozoös 2004, 17, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Smith, C.M.; Tumilty, S.; Cameron, C.; Treharne, G.J. How does dog-walking influence perceptions of health and wellbeing in healthy adults?A qualitative dog-walk-along study. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric Evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Terracciano, A.; Milaneschi, Y.; An, Y.; Ferrucci, L.; Zonderman, A.B. The trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult life span. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T.D.; Prina, M.; Stubbs, B.; Wu, Y.-T. Reliability and Validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in a Population-Based Cohort of Middle-Aged U.S. Adults. J. Nurs. Meas. 2017, 25, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2006, 34, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandek, B.; Ware, J.E.; Aaronson, N.K.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S.; Leplege, A.; Prieto, L.; et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, C.H.; Brown, J.D. Reliability and validity of the short-form 12 item version 2 (SF− 12v2) health-related quality of life survey and disutilities associated with relevant conditions in the US older adult population. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Guo, Y.; Shenkman, E.; Muller, K. Assessing the reliability of the short form 12 (SF-12) health survey in adults with mental health conditions: A report from the wellness incentive and navigation (WIN) study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.C.; Butterworth, P.; Rodgers, B.; Mackinnon, A. Validity of the mental health component scale of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (MCS-12) as measure of common mental disorders in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 152, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L.S.; Gamst, G.; Guarino, A. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Eltantawy, M.; Cole, S. A systematic review of pet attachment and health outcomes in older adults. University of Maryland School of Nursing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2025; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, L.H.; Schindler-Gmelch, L.; Rogge, L.; Berking, M. Walking the Black Dog: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effect of Walking Interventions on Depressive Symptoms. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 26, 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M. The pet connection: Pets as a conduit for social capital? Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Martin, K.; Christian, H.; Houghton, S.; Kawachi, I.; Vallesi, S.; McCune, S. Social capital and pet ownership–a tale of four cities. SSM-Popul. Health 2017, 3, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders-Slegers, M.-J.; Hediger, K. Pet ownership and human-animal interaction in an aging population: Rewards and challenges. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.M.; Underwood, L.; Carr, E.; Gross, D.P.; Kane, M.; Miciak, M.; Wallace, J.E.; Brown, C.A. Older women’s experiences of companion animal death: Impacts on well-being and aging-in-place. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, S.; Planchon, L.; Templer, D.; Keller, J. Death of a companion cat or dog and human bereavement: Psychosocial variables. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (N = 596) | Non-Pet Owner (n = 418) | Pet Owner (n = 178) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N or M | (%) or (SD) | N or M | (%) or (SD) | N or M | (%) or (SD) | p† |

| Dog owner, N (%) | 78 | (13.1) | 0 | n/a | 78 | (43.8) | |

| Cat owner, N (%) | 65 | (10.9) | 0 | n/a | 65 | (36.5) | |

| Age in years, M (SD) | 67.6 | (9.5) | 68.8 | (9.6) | 64.8 | (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Race: Black or African American, N (%) | 166 | (27.9) | 138 | (33.0) | 28 | (15.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex: Female, N (%) | 337 | (56.5) | 234 | (56.0) | 103 | (57.9) | 0.671 |

| BMI, M (SD) | 26.9 | (4.5) | 26.93 | (4.5) | 26.70 | (4.6) | 0.570 |

| Comorbidities, M (SD) | 0.9 | (1.2) | 0.98 | (1.1) | 0.80 | (1.2) | 0.079 |

| Education: < College Graduate, N (%) | 72 | (2.1) | 59 | (14.2) | 13 | (7.3) | 0.211 |

| Married or partnered, N (%) | 40 0 | (67.1) | 263 | (62.9) | 137 | (77.0) | <0.001 |

| Lives alone, N (%) | 150 | (25.2) | 119 | (28.5) | 31 | (17.4) | 0.005 |

| Single-family housing, N (%) | 493 | (82.7) | 325 | (77.8) | 168 | (94.4) | <0.001 |

| Family income exceeds USD 50K, N (%) | 482 | (80.9) | 329 | (78.7) | 159 | (85.48) | 0.127 |

| Anxiety (PSS), M (SD) | 4.5 | (3.0) | 4.3 | (3.0) | 4.8 | (3.2) | 0.087 |

| Depression (CES-D), M (SD) | 4.6 | (4.4) | 4.8 | (4.4) | 4.4 | (4.5) | 0.352 |

| Happiness, M (SD) | 8.9 | (5.6) | 9.1 | (6.6) | 8.4 | (1.4) | 0.163 |

| Mental Wellbeing (MCS), M (SD) | 55.6 | (5.6) | 55.5 | (5.6) | 55.8 | (5.4) | 0.574 |

| Outcome | Unstandardized Beta | Standard Error of Beta | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0.062 | 0.024 | 0.011 |

| Depression | 0.036 | 0.038 | 0.322 |

| Happiness | −0.102 | 0.048 | 0.037 |

| Mental Wellbeing † | −0.008 | 0.003 | 0.007 |

| Outcome | Unstandardized Beta | Standard Error of Beta | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | −0.0002 | −0.001 | 0.908 |

| Depression | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.952 |

| Happiness | 0.0019 | 0.002 | 0.338 |

| Mental Wellbeing † | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Friedmann, E.; Gee, N.R.; Simonsick, E.M.; Resnick, B.; Gurlu, M.; Adesanya, I.; Shim, S. Pet Ownership, Pet Attachment, and Longitudinal Changes in Psychological Health—Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060156

Friedmann E, Gee NR, Simonsick EM, Resnick B, Gurlu M, Adesanya I, Shim S. Pet Ownership, Pet Attachment, and Longitudinal Changes in Psychological Health—Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(6):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060156

Chicago/Turabian StyleFriedmann, Erika, Nancy R. Gee, Eleanor M. Simonsick, Barbara Resnick, Merve Gurlu, Ikmat Adesanya, and Soyeon Shim. 2025. "Pet Ownership, Pet Attachment, and Longitudinal Changes in Psychological Health—Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging" Geriatrics 10, no. 6: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060156

APA StyleFriedmann, E., Gee, N. R., Simonsick, E. M., Resnick, B., Gurlu, M., Adesanya, I., & Shim, S. (2025). Pet Ownership, Pet Attachment, and Longitudinal Changes in Psychological Health—Evidence from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Geriatrics, 10(6), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060156