Perceptions of Aging and Control Beliefs: A Study on Older Patients’ Views of Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. ZASSA Cohort

2.1.2. DEAS Cohort

2.2. Variables of Interest

2.3. Covariates

- Age (years, metric), sex (male/female, dichotomous);

- Marital state (single/married/widowed/separated, multinominal);

- Living situation (alone/with partner or family/assisted living/nursing home/others, multinominal);

- Cognitive function measured by Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) screens orientation, memory, attention, calculation, and language ability with a maximum of 30 points [18], and higher scores indicate better cognitive function;

- Geriatric depression screening scale (GDS): 15 items assessing emotion and behavior towards life [19], with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

- Linear models with robust standard errors.

- 2.

- Ordinal cumulative logit models.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Cohort

3.2. Locus of Control

3.3. Views on Aging

3.4. Association Between Locus of Control and Views on Aging

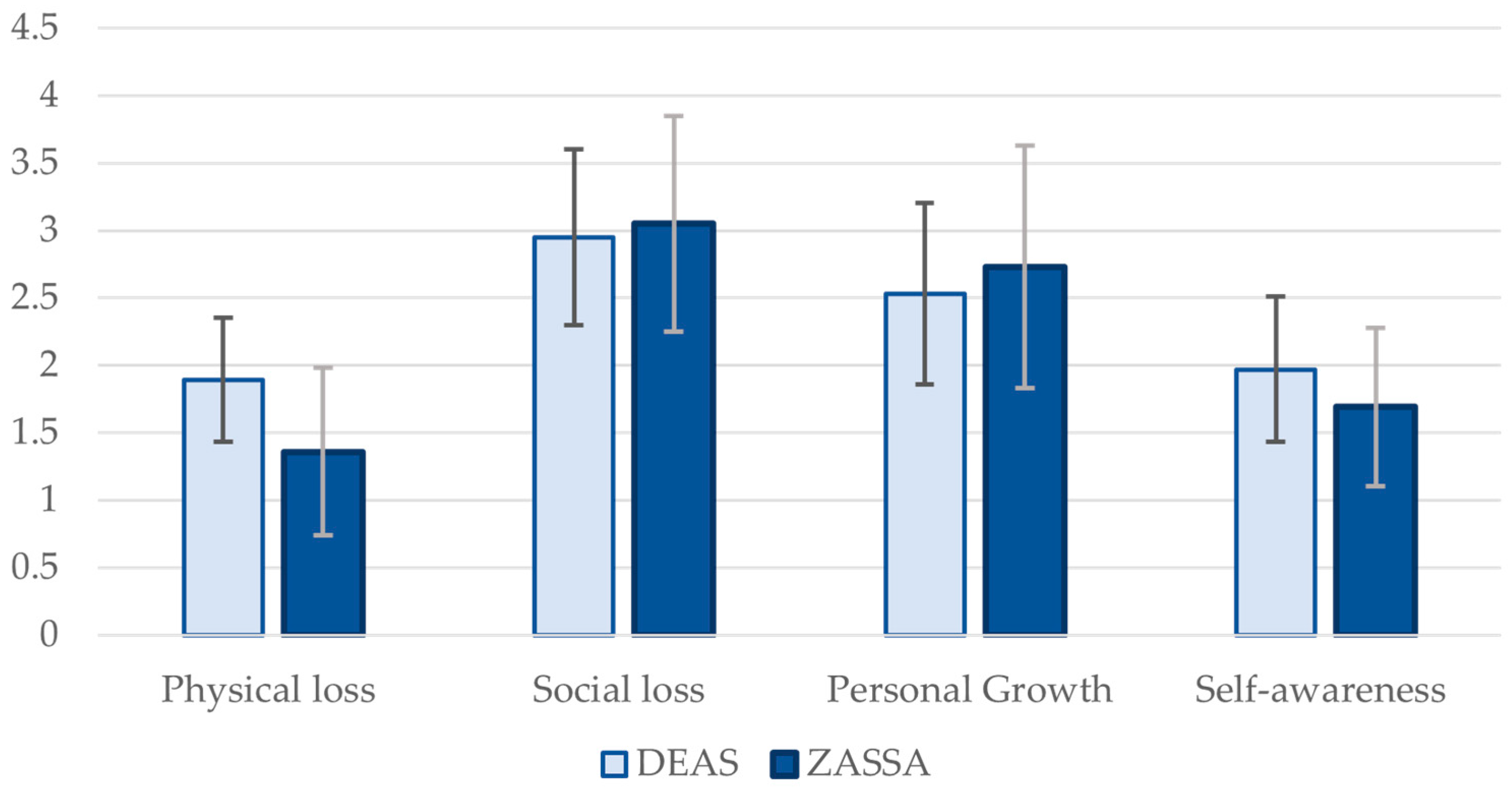

3.5. Comparison with the DEAS Cohort

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg (false discovery rate procedure) |

| CI | Confidence Interval (e.g., 95% CI) |

| CLM | Cumulative Link Model (proportional-odds ordinal regression) |

| DEAS | German Ageing Survey |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GDS | Geriatric Depression Scale |

| HC3 | Heteroskedasticity-Consistent (Type 3) covariance estimator |

| HS | Health Satisfaction |

| IE-4 | Internal–External Locus of Control short scale (4 items) |

| LoC | Locus of Control (internal, external) |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| VoA | Views on Aging |

| ZASSA | (Name of the hospital cohort; acute geriatric rehabilitation sample) |

References

- Diehl, M.; Wettstein, M.; Spuling, S.M.; Wurm, S. Age-related change in self-perceptions of aging: Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of change. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornadt, A.E.; Kessler, E.M.; Wurm, S.; Bowen, C.E.; Gabrian, M.; Klusmann, V. Views on ageing: A lifespan perspective. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneed, J.R.; Whitbourne, S.K. Models of the Aging Self. J. Soc. Issues 2005, 61, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully-Wilson, C.; Bojack, R.; Millear, P.M.; Stallman, H.M.; Allen, A.; Mason, J. Self-perceptions of aging: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmoth, K.; Tarrant, M.; Abraham, C.; Lang, I.A. Older adults’ perceptions of ageing and their health and functioning: A systematic review of observational studies. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 21, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, S.; Diehl, M.; Kornadt, A.E.; Westerhof, G.J.; Wahl, H.W. How do views on aging affect health outcomes in adulthood and late life? Explanations for an established connection. Dev. Rev. 2017, 46, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, R.A. Stereotypes of Aging: Their Effects on the Health of Older Adults. J. Geriatr. 2015, 2015, 954027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Bei, B.; Gilson, K.; Komiti, A.; Jackson, H.; Judd, F. The relationship between attitudes to aging and physical and mental health in older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Kim, H. Ageism and Psychological Well-Being Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 8, 23337214221087023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachman, M.E.; Neupert, S.D.; Agrigoroaei, S. Chapter 11—The Relevance of Control Beliefs for Health and Aging. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, 7th ed.; Schaie, K.W., Willis, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen, J.; Schulz, R. A life-span theory of control. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandtstädter, J.; Greve, W. The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Dev. Rev. 1994, 14, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashian, H.; Caskie, G. The Role of Aging Anxiety, Ageism, and Health Locus of Control on Middle-Aged Adults Health Outcomes and Behaviors. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, 604–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimrich, K.G.; Schönenberg, A.; Mendorf, S.; Lehmann, T.; Prell, T. Predictors of Functional Improvement During Comprehensive Geriatric Care in Germany: A 10-Year Monocentric Retrospective Analysis. Sage Open Aging 2025, 11, 30495334251346941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovaleva, A.; Beierlein, C.; Kemper, C.J.; Rammstedt, B. Eine Kurzskala zur Messung von Kontrollüberzeugung: Die Skala Internale-Externale-Kontrollüberzeugung-4 (IE-4); Working Papers; GESIS: Mannheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lübke, N.; Meinck, M.; Von Renteln-Kruse, W. The Barthel Index in geriatrics. A context analysis for the Hamburg Classification Manual. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2004, 37, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, S.; Schäfer, S.K. Gain- but not loss-related self-perceptions of aging predict mortality over a period of 23 years: A multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 123, 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbourne, S.K.; Collins, K.J. Identity processes and perceptions of physical functioning in adults: Theoretical and clinical implications. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1998, 35, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingtier, J.A.; Neupert, S.D. Feeling Young and in Control: Daily Control Beliefs Are Associated With Younger Subjective Ages. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, e13–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D. On the Inevitability of Aging: Essentialist Beliefs Moderate the Impact of Negative Age Stereotypes on Older Adults’ Memory Performance and Physiological Reactivity. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2016, 73, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliberti, S.M.; Capunzo, M. The Power of Environment: A Comprehensive Review of the Exposome’s Role in Healthy Aging, Longevity, and Preventive Medicine-Lessons from Blue Zones and Cilento. Nutrients 2025, 17, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Miche, M.; Brothers, A.F.; Barrett, A.E.; Diehl, M.; Montepare, J.M.; Wahl, H.W.; Wurm, S. The influence of subjective aging on health and longevity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Wurm, S. Subjective Aging and Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 82.38 ± 5.34 | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale, mean ± SD | 2.86 ± 2.85 | |

| Mini-Mental-Status-Examination, mean ± SD | 26.97 ± 2.74 | |

| Barthel index sum score, mean ± SD | 34.85 ± 11.62 | |

| VoA—Physical Losses, mean ± SD | 1.36 ±0.62 | |

| VoA Social Losses, mean ± SD | 3.05 ± 0.80 | |

| VoA Personal Growth, mean ± SD | 2.73 ± 0.90 | |

| VoA Gains, mean ± SD | 1.69 ± 0.59 | |

| LoC Internal, mean ± SD | 4.29 ± 0.83 | |

| LoC External, mean ± SD | 2.44 ± 1.02 | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 63 (61.2) |

| Male | 40 (38.8) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | Single | 2 (2.0) |

| Married | 29 (28.4) | |

| Widowed/Separated | 71 (69.6) | |

| Living situation, n (%) | Alone | 56 (56.0) |

| With Partner/Family | 37 (37.0) | |

| Others | 7 (7.0) | |

| LoC = Locus of Control, VOA = Views on Ageing | ||

| VoA Domain (Higher = More Positive) | Internal LoC—OLS β (95% CI), FDR-p | External LoC—OLS β (95% CI), FDR-p | Internal LoC—CLM OR (95% CI) | External LoC—CLM OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Loss | 0.133 (0.043–0.223), 0.035 | −0.165 (−0.285 to −0.045), 0.035 | 3.52 (1.31–13.10) | 0.274 (0.10–0.65) |

| Social Loss | 0.067 (−0.078–0.213), 0.539 | −0.149 (−0.314–0.016), 0.217 | 1.24 (0.83–1.89) | 0.649 (0.418–0.991) |

| Personal Growth (reversed) | 0.154 (−0.036–0.345), 0.231 | 0.021 (−0.208–0.249), 0.858 | 1.64 (1.04–2.72) | 1.05 (0.67–1.64) |

| Gains (reversed) | 0.054 (−0.093–0.202), 0.539 | −0.069 (−0.233–0.095), 0.539 | 1.25 (0.84–1.85) | 0.759 (0.51–1.14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schönenberg, A.; Kobus, C.; Günther, M.; Umfermann, L.; Prell, T. Perceptions of Aging and Control Beliefs: A Study on Older Patients’ Views of Aging. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060148

Schönenberg A, Kobus C, Günther M, Umfermann L, Prell T. Perceptions of Aging and Control Beliefs: A Study on Older Patients’ Views of Aging. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(6):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060148

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchönenberg, Aline, Charlotte Kobus, Marlene Günther, Luise Umfermann, and Tino Prell. 2025. "Perceptions of Aging and Control Beliefs: A Study on Older Patients’ Views of Aging" Geriatrics 10, no. 6: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060148

APA StyleSchönenberg, A., Kobus, C., Günther, M., Umfermann, L., & Prell, T. (2025). Perceptions of Aging and Control Beliefs: A Study on Older Patients’ Views of Aging. Geriatrics, 10(6), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060148