An Optimal Beneficiary Profile to Ensure Focused Interventions for Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

- I.

- Quantitative group: A total of 50 hospitalized older adults who completed standardized assessment tools. Sampling was non-probabilistic, with participants recruited from the “Ana Aslan” National Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics (NIGG).

- II.

- Qualitative group: Four focus-groups consisting of 17 participants (10 subjects from NIGG “Ana Aslan” and 7 subjects from GNSPY).

- For the quantitative group: age, level of education, cognitive function (assessed by CASE-SF), mobility status (categorized as independent, requiring a cane, or requiring a walker), and use of assistive devices (hearing aids, glasses, mobility aids).

- For the qualitative group: age distribution, educational attainment, history of yoga practice, cognitive function, mobility status, and perceived physical limitations.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- A.

- Demographic variable:

- Adults over the age of 65 years;

- Living in underserved areas of Bucharest (areas in which public transportation is not easy to access);

- Low incomes (pensions under RON 3000/month).

- B.

- Social variable:

- Loneliness (widower, single, divorced);

- Physical deficiencies, such as arthrosis, rheumatism, and reduced mobility;

- Mental dysfunctions, such as anxiety, depression, fear of aging, and impaired cognitive abilities.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Severe cognitive impairment (e.g., diagnosed dementia);

- Severe mobility limitations (e.g., bedridden individuals or those requiring full assistance for movement);

- Uncontrolled chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, advanced heart failure);

- Recent major surgeries (within the past three months);

- Severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, severe bipolar disorder);

- Lack of informed consent due to cognitive or legal incapacity.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Measures

- WHOQoL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale—Short Form):

- CASE-SF (Clinical Assessmenr Scales for the Elderly—Short Form):It assesses anxiety, depression, somatization, fear of aging, and cognitive competence. Each subscale score is derived by summing the individual item scores and normalizing them to a standardized scale, where higher scores indicate greater impairment [37].

- Subjective reports:Medical diagnoses were extracted from clinical records, not self-reported by participants. These diagnoses were not used as a numerical score but rather as contextual health information for participant profiling.

- Focus Groups:Explored perceptions, barriers, and motivational factors regarding yoga participation were measured. The 17 individuals in the focus groups were not part of the quantitative sample but were selected separately to assess their interest in yoga before any exposure to the intervention.

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Quantitative Data Collection

2.4.2. Qualitative Data Collection

2.4.3. Ethical and Confidentiality Considerations

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Analysis

2.5.2. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

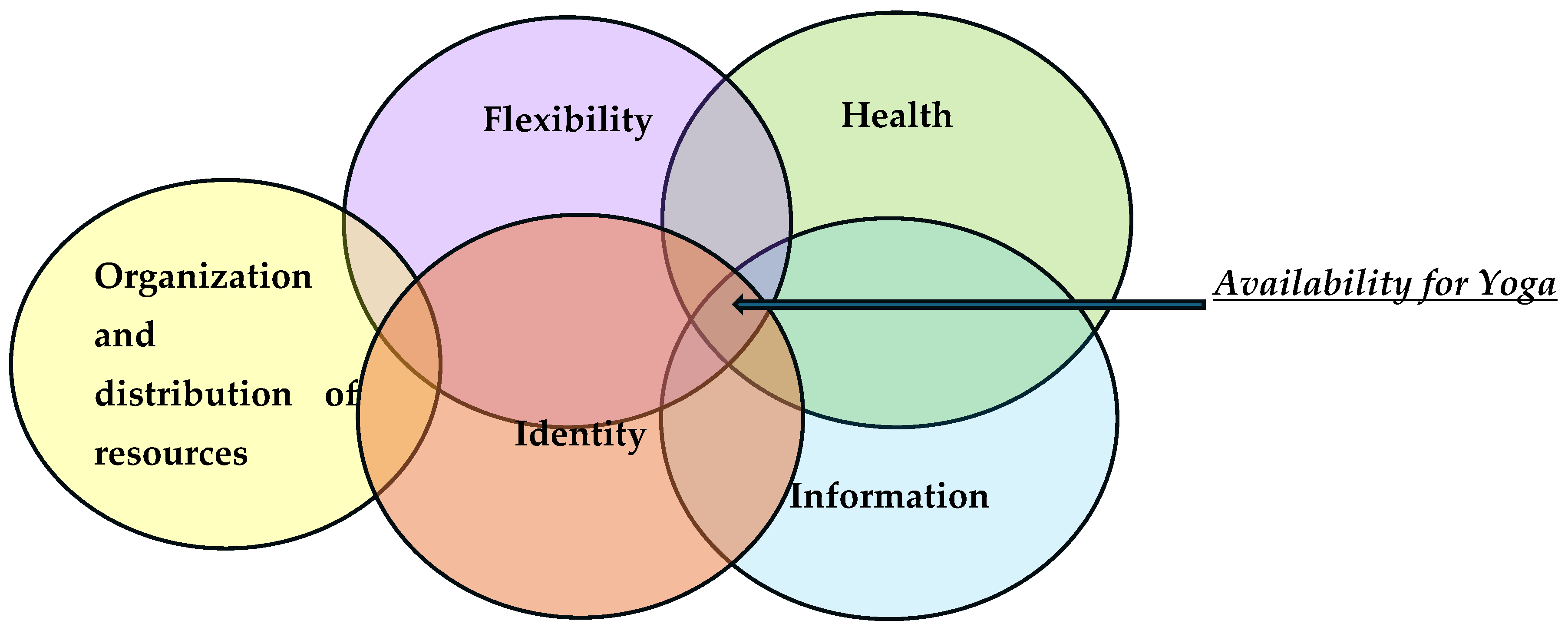

- (1)

- The Health theme includes a series of codes on three significant levels, namely physical, cognitive, and social.On a physical level, the subjects associate the idea of yoga with benefits in the sense of acquiring extra energy, protection against diseases, and performing slow movement adapted to the needs of older people. Codes with a negative role refer to the existence of a severe pathology with a disabling role. At the cognitive level, the idea of obtaining an improvement in mnesic and prosexic functions was identified. At the social level, the reasons are related to the opportunity for interaction and the inclusion of older people in groups.

- (2)

- The Information theme contains a series of reasons regarding the roles that information had when potential beneficiaries chose to participate. These roles both reinforce and block willingness to participate.As a positive impact, the thematic codes center around the idea that yoga includes varied and different forms, some of which are adapted to the dynamics of an older person and the support of participation from family and/or friends in this endeavor. As a blocking role, the information held is related to the sexualization of the concept of yoga and, as a consequence, to the presence of stereotypes and prejudices.

- (3)

- The Flexibility theme includes the reasons related to certain personality traits with the role of increasing the willingness to participate or cancel this openness.Thematic motifs that positively impact the willingness to participate in yoga classes refer to traits such as openness to the new, curiosity, not caring what others might say, and putting oneself first. Traits with a negative impact include resistance to change, convenience, and reluctance to new experiences [39].

- (4)

- The Organization and Distribution of Resources theme includes thematic reasons with a rather negative role in openness to participation.Within this theme, responsibility and roles in the extended family, a certain dynamic of personal life, limited financial resources, and reduced physical and spatical accessibility were identified as the general reasons that impact the willingness to participate in yoga classes. How a person is defined and how they relate to their roles lead to a certain identity and can have both positive and negative impacts.

- (5)

- The theme of Identity refers to those leitmotifs that describe certain attitudes and behaviors arising from personal history.

- The extent to which the goals of the older person are associated with the goals of the project:

- The way in which an older person’s motivations are associated with the specific elements of the project, namely the development of the competence of awareness of one’s own body, breathing, emotions, and thoughts, is adapted from yoga techniques in order to increase the quality of life.

- Identifying the general attitude about yoga by exploring existing stereotypes:

- Identifying the degree of mental flexibility, openness, and availability to new things:

3.3. Profile of the Optimal Beneficiary

- (1)

- Socio-demographic characteristics

- A single person: divorced, widower, single;

- A person with physical dysfunctions: arthrosis, rheumatism, impaired mobility;

- A person who does not have mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, moderate-major cognitive impairment;

- A person from the urban environment from insufficiently served peripheral areas;

- Older people: over 65 years.

- (2)

- Psychological characteristics

- A person who has an impaired quality of life and/or wishes to increase it;

- A person who has formed a perception and belief about yoga based on correct, undistorted information;

- A person who has received strengthening information about yoga over time from adjacent sources, such as family, friends, teachers;

- A person who checked their existing stereotypes through an informed check and who did not overgeneralize a negative event;

- A person who presents moderate mental flexibility;

- A person who shows openness to new things;

- A person who focuses on the present;

- A person with a spiritual identity that does oppose to yoga practices.

4. Discussion

Strenghts and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CASE-SF | Clinical Assessment Scales for the Elderly—Short Form |

| GNSPY | Grupul National de Studiu si Practica Yoga |

| NIGG | National Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire—Short Form |

References

- Kulik, C.; Ryan, S.; Harper, S.; George, G. Aging Populations and Management. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, S.M.; Annuar, N.; Rahman, N.L.A.; Musairah, S.K.; Mutalib, H.A.; Subagja, I.K. Major Trends in Ageing Population Research: A Bibliometric Analysis from 2001 to 2021. Proceedings 2022, 82, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, V.-R.; Iftimoaoei, C.; Baciu, I.-C. Population Ageing. Rom. Eur. Context Rom. J. Popul. Stud. 2022, 16, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/demography-2024 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Göthberg, H.; Skoog, I.; Tengstrand, T.; Magnusson, L.; Hoff, M.; Rosenhall, U.; Sadeghi, A. Pathophysiological and Clinical Aspects of Hearing Loss Among 85-Year-Olds. Am. J. Audiol. 2023, 32, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.G.; Hong, C.; Deal, J.A.; Bettcher, B.M.; Pelak, V.S.; Gross, A.; Jiang, K.; Swenor, B.; Wittich, W. Are cognitive researchers ignoring their senses? The problem of sensory deficit in cognitive aging research. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Li, Y.-Z.; Ou, Y.-N.; Yang, L.; Chen, S.-D.; Dong, Q.; Feng, J.-F.; Cheng, W.; Tan, L.; et al. Cataract, cataract surgery, and risk of incident dementia: A prospective cohort study of 300,823 participants. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Honvo, G.; Bruyère, O.; Rizzoli, R.; Barbagallo, M.; Maggi, S.; Smith, L.; Sabico, S.; Al-Daghri, N.; Cooper, C.; et al. Knee osteoarthritis and adverse health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 35, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, N.E. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194 (Suppl. S2), S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easter, M.; Bollenbecker, S.; Barnes, J.W.; Krick, S. Targeting aging pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Foundation. Diabetes Facts and Figures. 2022. Available online: https://www.idf.org/about-diabetes/facts-figures/ (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Choi, S.H.; Tanzi, R.E. Adult neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus 2023, 33, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noale, M.; Limongi, F.; Maggi, S. Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases in the Elderly. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1216, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, R.I.; Monte, M.J.; Serrano, M.A.; González-Santiago, J.M.; Martín-Arribas, I.; Simão, A.L.; Castro, R.E.; González-Gallego, J.; Mauriz, J.L.; Marin, J.J. Impact of aging on primary liver cancer: Epidemiology, pathogenesis and therapeutics. Aging 2021, 13, 23416–23434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntley, C.; Torr, B.; Sud, A.; Rowlands, C.F.; Way, R.; Snape, K.; Hanson, H.; Swanton, C.; Broggio, J.; Lucassen, A.; et al. Utility of polygenic risk scores in UK cancer screening: A modelling analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintas, S.; Loewenthal, J.V. Integrating Geriatrics and Lifestyle Medicine: Paving the Path to Healthy Aging. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2024, 19, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garfinkel, M.; Schumacher, H.R. YOGA. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2000, 26, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, J.; Singleton, M. Roots of Yoga; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Osth, J.; Diwan, V.; Jirwe, M.; Diwan, V.; Choudhary, A.; Mahadik, V.K.; Pascoe, M.; Hallgren, M. Effects of yoga on well-being and healthy ageing: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (FitForAge). BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallath, N. Perspectives on yoga inputs in the management of chronic pain. Indian J. Palliat Care 2010, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Deshpandae, A.; Joshi, S.R. Therapeutic Role of Yoga in Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 33, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.A.; Van Puymbroeck, M.; Altenburger, P.A.; Schalk, N.L.; Dierks, T.A.; Miller, K.K.; Damush, T.M.; Bravata, D.M.; Williams, L.S. Poststroke balance improves with yoga: A pilot study. Stroke 2012, 43, 2402–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koncz, A.; Nagy, E.; Csala, B.; Körmendi, J.; Gál, V.; Suhaj, C.; Selmeci, C.; Bogdán, Á.S.; Boros, S.; Köteles, F. The effects of a complex yoga-based intervention on healthy psychological functioning. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1120992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Youkhana, S.; Dean, C.M.; Wolff, M.; Sherrington, C.; Tiedemann, A. Yoga-based exercise improves balance and mobility in people aged 60 and over: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, G.A.; Howsam, J.; Hardy, M.; Bissell, L. Adapted yoga to improve physical function and health-related quality of life in physically-inactive older adults: A randomised controlled pilot trial. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Rudrauf, D.; Feinstein, J.S.; Tranel, D. The pathways of interoceptive awareness. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1494–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bornemann, B.; Herbert, B.M.; Mehling, W.E.; Singer, T. Differential changes in self-reported aspects of interoceptive awareness through 3 months of contemplative training. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eurich, T. What self-awareness really is (and how to cultivate it). Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt, J.; Adlin, T. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-12-566251-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. The Challenges of Intersectionality in the Lives of Older Adults Living in Rural Areas with Limited Financial Resources. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211009363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mustaquim, M.M. A Study of Universal Design in Everyday Life of Elderly Adults. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 67, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinsante, S.; Strazza, A.; Dobre, C.; Bajenaru, L.; Mavromoustakis, C.X.; Batalla, J.M.; Krawiec, P.; Georgescu, G.; Molan, G.; Gonzalez-Velez, H.; et al. Integrated Consumer Technologies for Older Adults’ Quality of Life Improvement: The vINCI Project. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Consumer Technologies (ISCT), Ancona, Italy, 19–21 June 2019; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băjenaru, L.; Marinescu, I.A.; Dobre, C.; Drăghici, R.; Herghelegiu, A.M.; Rusu, A. Identifying the needs of older people for personalized assistive solutions in Romanian healthcare system. Stud. Inform. Control 2020, 29, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Steinbüchel, N.; Lischetzke, T.; Gurny, M.; Eid, M. Assessing quality of life in older people: Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF. Eur. J. Ageing 2006, 3, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Drăghici, R.; Rusu, A.; Prada, G.I.; Herghelegiu, A.M.; Bajenaru, L.; Dobre, C.; Mavromoustakis, C.X.; Spinsante, S.; Batalla, J.M.; Gonzalez-Velez, H. Acceptability of Digital Quality of Life Questionnaire Corroborated with Data from Tracking Devices. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 24th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD), Limassol, Cyprus, 11–13 September 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băjenaru, L.; Marinescu, I.A.; Tomescu, M.; Drăghici, R. Assessing elderly satisfaction in using smart assisted living technologies: VINCI case study. Rom. J. Inf. Technol. Autom. Control 2022, 32, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Bigler, E.D. CASE™-SF Clinical Assessment Scales for the Elderly™ Short Form. Available online: https://www.parinc.com/products/CASE-SF (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schnepf, S.V.; d’Hombres, B.; Mauri, C. Loneliness in Europe. Determinants, Risks and Interventions; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Source of Data: Kantar Romania. Studiul “Explorarea si Masurarea Singuratatii la Persoanele Varstnice din Romania”, Asociatia “Niciodata Singur—Prietenii Varstnicilor”, 27 Sept.–12 Oct. 2021. Available online: www.mediafax.ro/social/singuratatea-afecteaza-1-din-4-varstnici-din-romania (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Eurostat. Overall Life Satisfaction by Sex, Age and Educational Attainmen; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, E.; Freeman, H.; Vladagina, N.F.; Brems, C. Popular Media Images of Yoga: Limiting Perceived Access to a Beneficial Practice. Media Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Šorytė, R. The Swedish Asylum Case of Gregorian Bivolaru, 2005. J. CESNUR 2022, 6, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.L.; Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Groessl, E.J.; Elwy, A.R.; Lee, S.Y. Exploring how different types of yoga change psychological resources and emotional well-being across a single session. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R.; Dassel, K.; Felsted, K.F.; Towsley, G.; Edelman, L. Yoga for seniors: Understanding their beliefs and barriers to participation. Educ. Gerontol. 2020, 46, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertman, A. An Exploration into Pathways, Motivations, Barriers and Experiences of Yoga Among Middle-Aged and Older Adult. Gerontology Thesis 2013. Available online: https://summit.sfu.ca/person/34989 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Patel, N.K.; Akkihebbalu, S.; Espinoza, S.E.; Chiodo, L.K. Perceptions of a Community-Based Yoga Intervention for Older Adults. Act. Adapt. Aging 2011, 35, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| I. Introduction and Welcome |

| Ethics and confidentiality; |

| Purpose and theme presentation; |

| The story of the name; |

| Group rules. |

| II. Introduction Questions |

| Objective: The debate initiation and participants familiarization with the dynamics of the interaction. |

|

|

|

| III. Key questions |

| Objective 1: Identification of participants opinion about yoga. |

|

|

|

| Objective 2: Determination of the usefulness level of a yoga program for increasing and promoting well-being and inclusion stimulation. |

|

|

| Objective 3: Identification of reasons why participants would or would not follow a yoga program. |

|

|

| M | SD | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.06 | 5.63 | −0.07 | −1.66 | 0.105 |

| Anxiety CASE-SF | 38.42 | 10.75 | −0.04 | −1.42 | 0.164 |

| Depression CASE-SF | 40.86 | 9.88 | −0.05 | −1.13 | 0.267 |

| Somatization CASE-SF | 38.86 | 9.10 | −0.02 | −0.36 | 0.720 |

| Fear of Aging CASE-SF | 41.21 | 13.36 | 0.06 | 1.58 | 0.122 |

| Cognition CASE-SF | 44.90 | 13.28 | −0.05 | −1.21 | 0.232 |

| WHOQOL-BREF | 99.32 | 15.38 | −0.04 | −1.92 | 0.061 |

| M | SD | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical diagnosis | 0.12 | 0.33 | 1.65 | 2.73 | 0.009 |

| Mental diagnosis | 0.78 | 0.42 | −1.12 | −2.36 | 0.023 |

| Theme | Codes | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Health | Positive: Acquiring extra energy Protection against diseases Physical exercise Social inclusion of elderly people Opportunity for social interaction Negative: Severe debilitating pathologies | “Being several people we communicate, it’s different than sitting alone and thinking, you communicate, one says one thing, one says another...” |

| “Socialization, yoga sessions open your horizons a bit and you socialize better... And the brain, you still have contact with one, with another. If you stay locked in a room being old, not having contact with so-and-so, you don’t talk to anyone anymore...” | ||

| “I felt that I entered a community. So it was a matter of emotional compatibility, so I say that the spiritual part also worked a lot for me...” | ||

| “An inclusion in a community that has maintained and developed beautifully and even supports me in times of trouble…” | ||

| “Me because I have a tumultuous life, I have friends, I have children, I have children who take special care of me, my life is not static, not “oh, is someone calling me?”, it seems to me that it would be the same with socializing…” | ||

| “It relaxes the mind, the body, and at our age I think it’s very good...” | ||

| “And for mind, because the body has aged, the mind has also aged, you no longer think like you did when you were young, you used to think seven, now one and you remember after I don’t know how long and for memory more would be...” | ||

| “For the benefit of the memory, I’m sure that the meditations there helped a lot the memory, any meditation helps a lot the memory...” | ||

| “I think it’s good for the health, it balances the psyche and it’s also a pleasure after all...” | ||

| “I noticed that I felt better, I wasn’t so dizzy anymore, I didn’t trust my legs anymore, they were shaking. Now these symptoms have started to disappear...” | ||

| “I think that during these years, it was what balanced me and supported me because I needed something like that and so it was, not only physical, that I always liked to move, so I enjoyed what I did of...” | ||

| “I was going to work mentally, to understand something from this life that basically we all have, a search and there was also another family...” | ||

| “I learned a lot from yoga to be observant, to observe yourself, so that was essential in life. There were some life criteria that guided me later...” | ||

| “It gave me a balance here and this attention to myself and to those around me helped me a lot...” | ||

| “For me it meant a great awareness, the very first time I realized that I need to be aware of some things both physically and psychologically. Social really meant that too, an inclusion in a community that has maintained and developed beautifully and even supports the times when I’m in trouble...” | ||

| “I would get up in the morning, do my yoga routine, and suddenly I was a different person. I had energy, I had how to say, power and mental.” | ||

| 2. Information | Positive: Varied and different forms of yoga Support from family and friends Negative: Sexualisation of yoga Stereotypes Prejudices | “About yoga, I was left with a bitter taste, why, I received the information that this Mr. Bivolaru was recruiting young people, raping them, forcing them to be there, this was the message I received...” |

| “I remembered that I was talking with a colleague about yoga and the first thing she said was “oh, I’m not going, because it seems like I’m having group sex!”. Speaking of Bivolaru. So the world was left with a negative perception...” | ||

| “If they hear about Bivolaru and you say you do yoga, the world can say—who knows what he did over there, that’s why he went—Romanian mentality!...” | ||

| “I heard about yoga when there was that conversation with... Guru, what does he call it...” | ||

| “In the area where I live, there was Bivolaru, in a tall house with one floor, there were always blinds shot, all the time, people said at the beginning it was prostitution, people said they were making some sexy videos, but no one knew what was going on there...” | ||

| “I first heard from my children about it, they had a teacher who went at this classes, he liked it, went...” | ||

| 3. Flexibility | Positive: Openness to new experiences Curiosity Prioritizing oneself Not caring what others say Negative: Resistence to change Convenience Rigidity to new experiences | “It’s a matter of laziness and fear to start something...” |

| “For me, for example, it’s a necessity. For us, the necessity is in the family, we live in a group, with the grandparents, so basically you allocate your time in what you are actually attracted and of course you feel good too, I mean each of us has this job of doing something for others... I didn’t have this and I turned to yoga...” | ||

| “There are some habits, I made my schedule, I drink my coffee, I have to go to the toilet and only after that do I start my schedule at a certain time. So it’s those habits we get into that we don’t want to get out of...” | ||

| “I didn’t agree with yoga because I personally have a slightly different body than the majority. I have some stuff that doesn’t fit the standard. And I focused on religious thinking...” | ||

| “I am going to parallel and to the church and coming and in yoga, I think I found the meaning more on the other side, and here I found support and balance...” | ||

| 4. Organization and distribution of resources | Positive: Roles within the extended family Negative: Limited financial resources Reduced accessibility | “I don’t know if my health would allow me. I have problems: with my heart, with my gland, with my liver, if I make ten steps faster, my blood pressure goes up. And then I don’t know if I could participate in any classes...” |

| “I might not be able to do certain things and that’s the only reason that would stop me...” | ||

| “I’ve talked to some people who consider themselves too old, so 72-year-olds who already think they’re no longer capable, to do something...” | ||

| “There are also financial aspects that would impact...” | ||

| “The lack of correct information. That is, when they see that there are only ads with sexy girls, without... and they don’t see people moving either a little more...” | ||

| 5. Identity | Positive: Willingness to evolve Need for belonging Need for a paradigm shift Resilience resources Negative: Rigid religious beliefs | “Since I also go to church, I think I find more meaning there, while here I found my support and balance...” |

| “For me it started from a personal need. Traditionally, this need is fulfilled within the family, where we live as a group—with grandparents, nephews, and so you are basically necessary. Therefore you allocate your time to something that attracts you and makes you feel good, so each of us has this need to do something for others... I did not have that, therefore I started doing yoga...” | ||

| “I did not agree with participating in yoga activities, because I have a bit of a different body when compared to the great majority of people. I have some traits that do not fit the standard. As a result, I centred myself on religious thinking...” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bălan, D.-C.; Drăghici, R.; Găiculescu, I.; Rusu, A.; Stan, A.-E.; Stan, P. An Optimal Beneficiary Profile to Ensure Focused Interventions for Older Adults. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10020059

Bălan D-C, Drăghici R, Găiculescu I, Rusu A, Stan A-E, Stan P. An Optimal Beneficiary Profile to Ensure Focused Interventions for Older Adults. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(2):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10020059

Chicago/Turabian StyleBălan, Dorina-Claudia, Rozeta Drăghici, Ioana Găiculescu, Alexandra Rusu, Andrada-Elena Stan, and Polixenia Stan. 2025. "An Optimal Beneficiary Profile to Ensure Focused Interventions for Older Adults" Geriatrics 10, no. 2: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10020059

APA StyleBălan, D.-C., Drăghici, R., Găiculescu, I., Rusu, A., Stan, A.-E., & Stan, P. (2025). An Optimal Beneficiary Profile to Ensure Focused Interventions for Older Adults. Geriatrics, 10(2), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10020059