Investigation and Correlation Analysis of Pathogens Carried by Ticks and Cattle in Tumen River Basin, China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

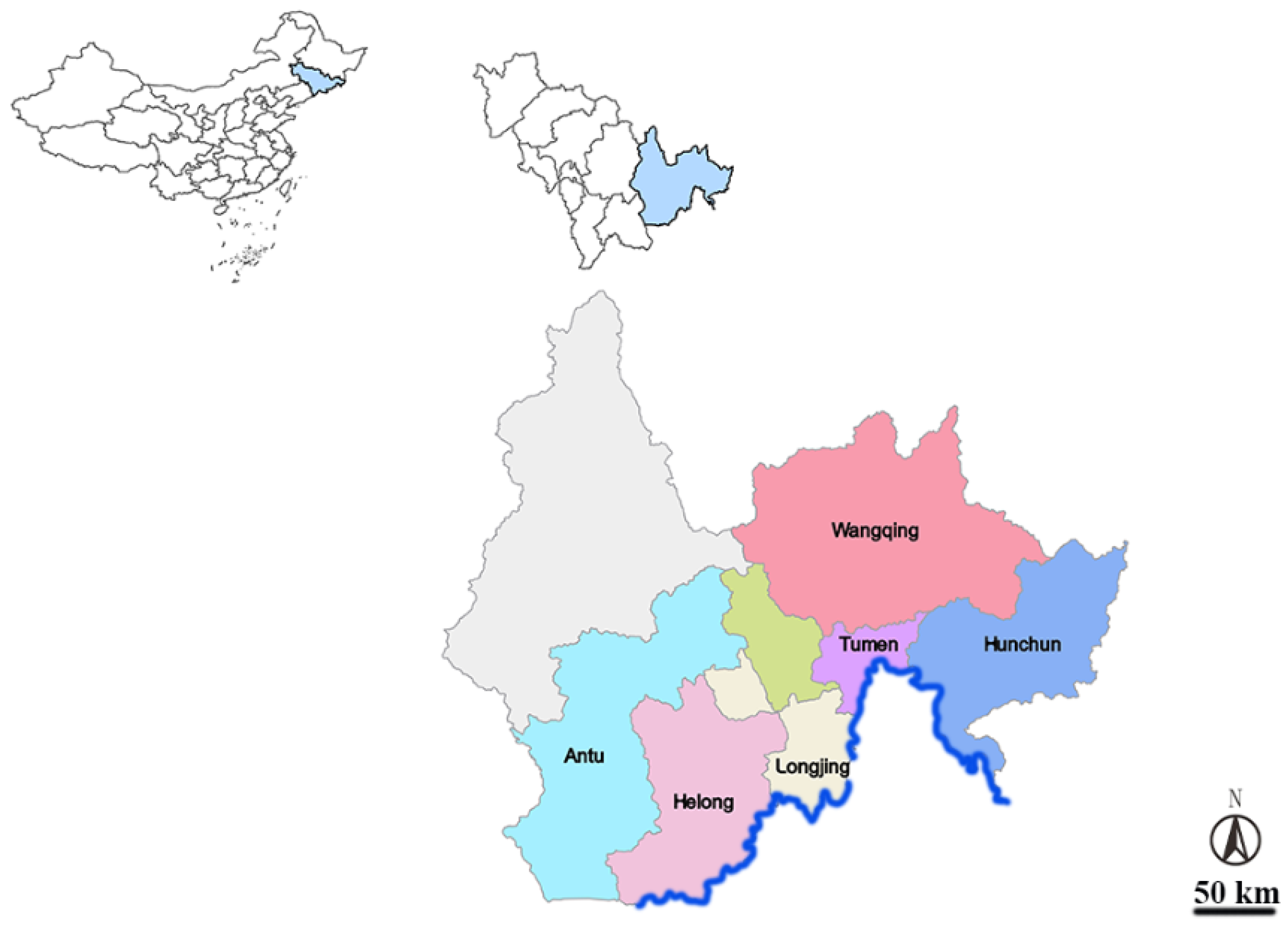

2.1. Sample Collection

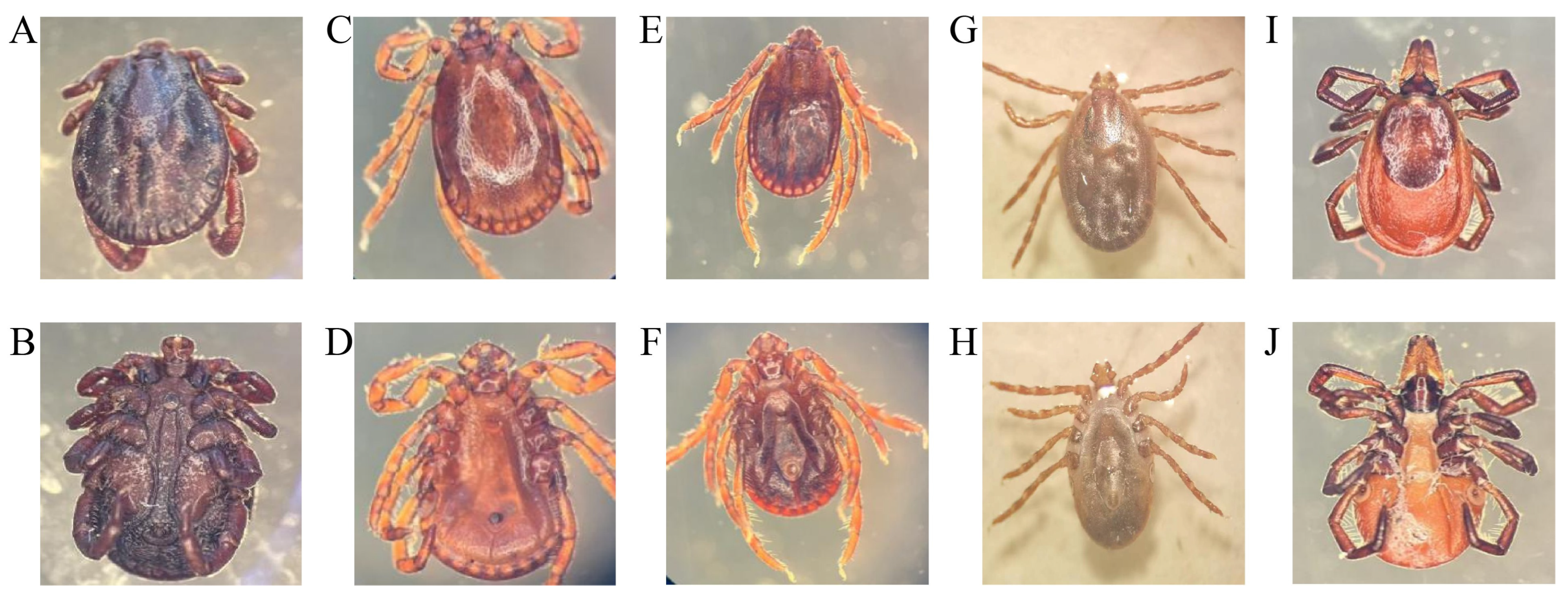

2.2. Tick Classification and Nucleic Acid Extraction

2.3. Bovine Blood Nucleic Acid Extractio

2.4. Detection of Pathogens in Ticks and Bovine Blood

2.5. Sequence Identity and Phylogenetic Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tick Species Survey Results

3.2. Results of Pathogen Investigation

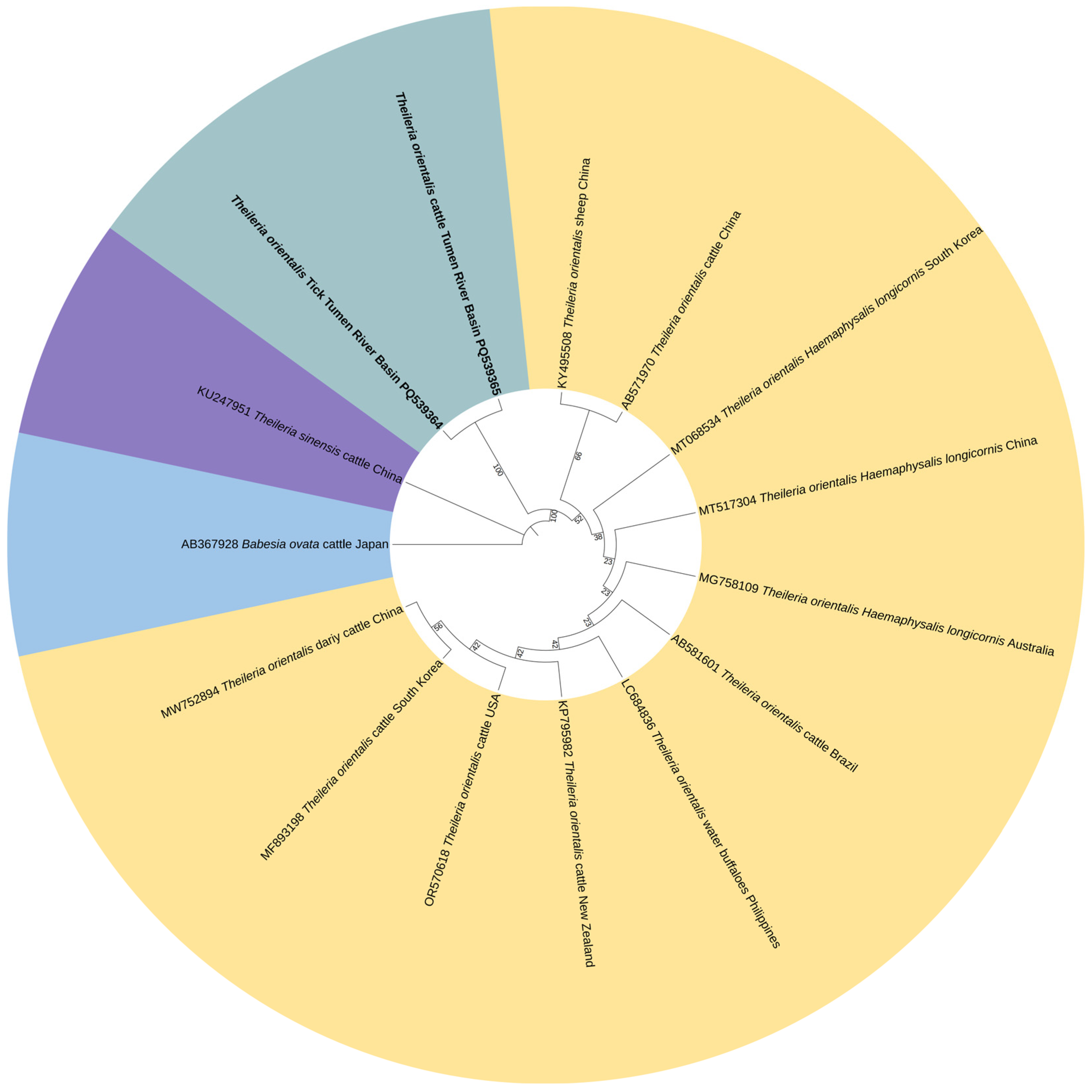

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of Pathogen

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hornok, S.; Abichu, G.; Meli, M.L.; Tanczos, B.; Sulyok, K.M.; Gyuranecz, M.; Gonczi, E.; Farkas, R.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Influence of the biotope on the tick infestation of cattle and on the tick-borne pathogen repertoire of cattle ticks in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongejan, F.; Uilenberg, G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology 2004, 129, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.F.; Magnarelli, L.A. Biology of ticks. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 22, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beati, L.; Klompen, H. Phylogeography of Ticks (Acari: Ixodida). Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Y.; Rojas, M.; Gershwin, M.E.; Anaya, J.M. Tick-borne diseases and autoimmunity: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 88, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffle, M.; Littwin, N.; Muders, S.V.; Petney, T.N. The ecology of tick-borne diseases. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 1059–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, D.D.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Otranto, D. Vector-borne parasitic zoonoses: Emerging scenarios and new perspectives. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 182, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L. The Impacts of Climate Change on Ticks and Tick-Borne Disease Risk. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.P.; Wang, Y.X.; Fan, Z.W.; Ji, Y.; Liu, M.J.; Zhang, W.H.; Li, X.L.; Zhou, S.X.; Li, H.; Liang, S.; et al. Mapping ticks and tick-borne pathogens in China. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, P.; Raoult, D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: An emerging infectious threat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 897–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.; Kahl, O.; Zintl, A. Pathogens transmitted by Ixodes ricinus. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2024, 15, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uilenberg, G. Babesia—A historical overview. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 138, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, G.; Lyu, C.; Hu, Y.; An, Q.; Qiu, H.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, C.R. Prevalence of Theileria in cattle in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 162, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Tsuchiya, K.; Zhu, W.; Okuro, T. Vegetation dynamics of abandoned paddy fields and surrounding wetlands in the lower Tumen River Basin, Northeast China. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda, J.; Hernandez-Silva, D.J.; Ueti, M.W.; Cruz-Resendiz, A.; Marquez-Cervantez, R.; Valdez-Espinoza, U.M.; Dang-Trinh, M.A.; Nguyen, T.T.; Camacho-Nuez, M.; Mercado-Uriostegui, M.A.; et al. Spherical Body Protein 4 from Babesia bigemina: A Novel Gene That Contains Conserved B-Cell Epitopes and Induces Cross-Reactive Neutralizing Antibodies in Babesia ovata. Pathogens 2023, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, N.; Mizuno, D.; Kuboki, N.; Igarashi, I.; Nakamura, Y.; Yamashina, H.; Hanzaike, T.; Fujii, K.; Onoe, S.; Hata, H.; et al. Epidemiological survey of Theileria orientalis infection in grazing cattle in the eastern part of Hokkaido, Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009, 71, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Guan, G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Leblanc, N.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Ma, M.; Niu, Q.; Ren, Q.; et al. Detecting and differentiating Theileria sergenti and Theileria sinensis in cattle and yaks by PCR based on major piroplasm surface protein (MPSP). Exp. Parasitol. 2010, 126, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Dang-Trinh, M.A.; Higuchi, L.; Mosqueda, J.; Hakimi, H.; Asada, M.; Yamagishi, J.; Umemiya-Shirafuji, R.; Kawazu, S.I. Initiated Babesia ovata Sexual Stages under In Vitro Conditions Were Recognized by Anti-CCp2 Antibodies, Showing Changes in the DNA Content by Imaging Flow Cytometry. Pathogens 2019, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemiya-Shirafuji, R.; Hatta, T.; Okubo, K.; Sato, M.; Maeda, H.; Kume, A.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I.; Tsuji, N.; Fujisaki, K.; et al. Transovarial persistence of Babesia ovata DNA in a hard tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, in a semi-artificial mouse skin membrane feeding system. Acta Parasitol. 2018, 63, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Hatta, T.; Alim, M.A.; Tsubokawa, D.; Mikami, F.; Kusakisako, K.; Matsubayashi, M.; Umemiya-Shirafuji, R.; Tsuji, N.; Tanaka, T. Initial development of Babesia ovata in the tick midgut. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 233, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, K.R.; Saravanan, B.C.; Jeeva, K.; Chandra, D.; Singh, K.P.; Ghosh, S.; Tewari, A.K. Oriental theileriosis associated with a new genotype of Theileria orientalis in buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) calves in Uttar Pradesh, India. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.T.; Garrett, K.B.; Kirchgessner, M.; Ruder, M.G.; Yabsley, M.J. A survey of piroplasms in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the southeastern United States to determine their possible role as Theileria orientalis hosts. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2022, 18, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.; Attia, K.; AlKahtani, M.D.F.; Albohairy, F.M.; Shoulah, S. Molecular epidemiology and genetic characterization of Theileria orientalis in cattle. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agina, O.A.; Cheah, K.T.; Sayuti, N.S.A.; Shaari, M.R.; Isa, N.M.M.; Ajat, M.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Mazlan, M.; Hamzah, H. High Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor to Interleukin 10 Ratio and Marked Antioxidant Enzyme Activities Predominate in Symptomatic Cattle Naturally Infected with Candidatus Mycoplasma haemobos, Theileria orientalis, Theileria sinensis and Trypanosoma evansi. Animals 2021, 11, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhao, S.; Xie, S.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S. Molecular prevalence of Theileria infections in cattle in Yanbian, north-eastern China. Parasite 2020, 27, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Han, S.; Yuan, G.; Wang, S.; He, H. The Common Occurrence of Theileria ovis in Tibetan Sheep and the First Report of Theileria sinensis in Yaks from Southern Qinghai, China. Acta Parasitol. 2021, 66, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M.F.; Meshnick, S.R. Pilot study assessing the effectiveness of long-lasting permethrin-impregnated clothing for the prevention of tick bites. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011, 11, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, V.B.; Miller, J.A.; Hadfield, T.; Burge, R.; Schech, J.M.; Pound, J.M. Control of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) with topical self-application of permethrin by white-tailed deer inhabiting NASA, Beltsville, Maryland. J. Vector Ecol. 2003, 28, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jordan, R.A.; Schulze, T.L.; Dolan, M.C. Efficacy of plant-derived and synthetic compounds on clothing as repellents against Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2012, 49, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostfeld, R.S.; Keesing, F. Does Experimental Reduction of Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes scapularis) Abundance Reduce Lyme Disease Incidence? Pathogens 2023, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grear, J.S.; Koethe, R.; Hoskins, B.; Hillger, R.; Dapsis, L.; Pongsiri, M. The effectiveness of permethrin-treated deer stations for control of the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis on Cape Cod and the islands: A five-year experiment. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Vicente, S.; Tokarz, R. Tick-Borne Co-Infections: Challenges in Molecular and Serologic Diagnoses. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarz, R.; Lipkin, W.I. Discovery and Surveillance of Tick-Borne Pathogens. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vicente, S.; Tagliafierro, T.; Coleman, J.L.; Benach, J.L.; Tokarz, R. Polymicrobial Nature of Tick-Borne Diseases. mBio 2019, 10, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathogen Gene | Primer Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. ovata CCTeta | P1 | GCCCGCAGGTCATCATAAAGT | 1008 | [15] |

| P2 | CATTTTGTGCCAGCGTTTTG | |||

| T. orientalis MPSP | P3 | CCAAGTTCACCCCAACTGTCG | 499 | [16] |

| P4 | GCACTGTTCATGGCGTGCAAA | |||

| T. sinensis MPSP | P5 | CACTGCTATGTTGTCCAAGAGATATT | 887 | [17] |

| P6 | AATGCGCCTAAAGATAGTAGAAAAC |

| Pathogen Gene | Pre-Denaturation Temperature (°C) /Time (s) | Denaturation Temperature (°C) /Time (s) | Annealing Temperature (°C) /Time (s) | Stretching Temperature (°C) /Time (s) | Temperature of Re-Extension (°C) /Time (s) | Cycle | Storage Temperature (°C) /Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. ovata CCTeta | 95/300 | 95/30 | 51.4/30 | 72/30 | 72/480 | 35 | 4 |

| T. orientalis MPSP | 94/300 | 94/60 | 58/60 | 72/60 | 72/420 | 35 | 4 |

| T. sinensis MPSP | 94/300 | 94/60 | 56/60 | 72/60 | 72/420 | 35 | 4 |

| Location | Haemaphysalis longicornis | Ixodes persulcatus | Haemaphysalis japonica | Dermacentor silvarum | Haemaphysalis concinna | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Constituent Ratio (%) | Quantity | Constituent Ratio (%) | Quantity | Constituent Ratio (%) | Quantity | Constituent Ratio (%) | Quantity | Constituent Ratio (%) | Quantity | Constituent Ratio (%) | |

| Hunchun | 136 | 55.97 | 7 | 2.88 | 8 | 3.29 | 63 | 25.93 | 29 | 11.93 | 243 | 100.00 |

| Tumen | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 3.39 | 47 | 79.66 | 10 | 16.95 | 59 | 100.00 |

| Yanji | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 33 | 15.00 | 165 | 75.00 | 22 | 10.00 | 220 | 100.00 |

| Helong | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 19 | 76.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 24.00 | 25 | 100.00 |

| Longjing | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 3.11 | 31 | 16.06 | 59 | 30.57 | 97 | 50.26 | 193 | 100.00 |

| Antu | 12 | 8.45 | 20 | 14.09 | 34 | 23.94 | 76 | 53.52 | 0 | 0.00 | 142 | 100.00 |

| Wangqing | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 19.35 | 25 | 80.65 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 31 | 100.00 |

| Total | 148 | 16.21 | 39 | 4.27 | 152 | 16.65 | 410 | 44.91 | 164 | 17.96 | 913 | 100.00 |

| Variable | Babesia ovata Positive Rate (%) | Theileria orientalis Positive Rate (%) | Theileria sinensis Positive Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||

| Hunchun | 11.11 | 25.11 | 2.88 |

| Tumen | 3.39 | 1.69 | 0.00 |

| Yanji | 2.72 | 5.45 | 0.00 |

| Helong | 8.00 | 28.00 | 4.00 |

| Longjing | 3.10 | 3.62 | 0.00 |

| Antu | 2.81 | 9.85 | 0.00 |

| Wangqing | 19.35 | 20.58 | 0.00 |

| Type | |||

| Haemaphysalis longicornis | 18.91 | 42.56 | 2.70 |

| Ixodes persulcatus | 5.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Haemaphysalis japonica | 11.25 | 12.12 | 2.64 |

| Dermacentor silvarum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Haemaphysalis concinna | 1.21 | 11.51 | 0.00 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5.83 | 13.70 | 0.00 |

| Female | 6.40 | 11.60 | 1.37 |

| Nymph | 0.00 | 6.50 | 0.16 |

| Ambient | |||

| Forest | 5.10 | 11.60 | 0.00 |

| Grass | 6.41 | 13.27 | 0.88 |

| Body surface | 5.70 | 4.20 | 5.71 |

| Variable | Babesia ovata Positive Rate (%) | Theileria orientalis Positive Rate (%) | Theileria sinensis Positive Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||

| Hunchun | 26.75 | 54.65 | 31.39 |

| Yanji | 0.00 | 10.81 | 18.92 |

| Helong | 7.89 | 31.57 | 63.15 |

| Longjing | 38.09 | 16.67 | 40.47 |

| Antu | 45.45 | 38.63 | 20.45 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24.49 | 38.46 | 32.87 |

| Female | 25.96 | 30.77 | 35.58 |

| Management | |||

| Graze | 27.38 | 35.71 | 36.9 |

| Farm | 20.25 | 34.18 | 27.85 |

| Age | |||

| <1 years old | 26.92 | 40.38 | 32.69 |

| 1–2 years old | 25.00 | 31.67 | 35.83 |

| >2 years old | 24.00 | 37.33 | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Min, P.; Song, J.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lin, S.; Zhao, F.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; et al. Investigation and Correlation Analysis of Pathogens Carried by Ticks and Cattle in Tumen River Basin, China. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010078

Min P, Song J, Meng Y, Zhao S, Tang Z, Wang Z, Lin S, Zhao F, Liu M, Wang L, et al. Investigation and Correlation Analysis of Pathogens Carried by Ticks and Cattle in Tumen River Basin, China. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Pengfei, Jianchen Song, Yinbiao Meng, Shaowei Zhao, Zeyu Tang, Zhenyu Wang, Sicheng Lin, Fanglin Zhao, Meng Liu, Longsheng Wang, and et al. 2026. "Investigation and Correlation Analysis of Pathogens Carried by Ticks and Cattle in Tumen River Basin, China" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010078

APA StyleMin, P., Song, J., Meng, Y., Zhao, S., Tang, Z., Wang, Z., Lin, S., Zhao, F., Liu, M., Wang, L., & Jia, L. (2026). Investigation and Correlation Analysis of Pathogens Carried by Ticks and Cattle in Tumen River Basin, China. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010078