Analysis of 2.0 and 3.5 mm Cortical Bone Screw Dimensions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

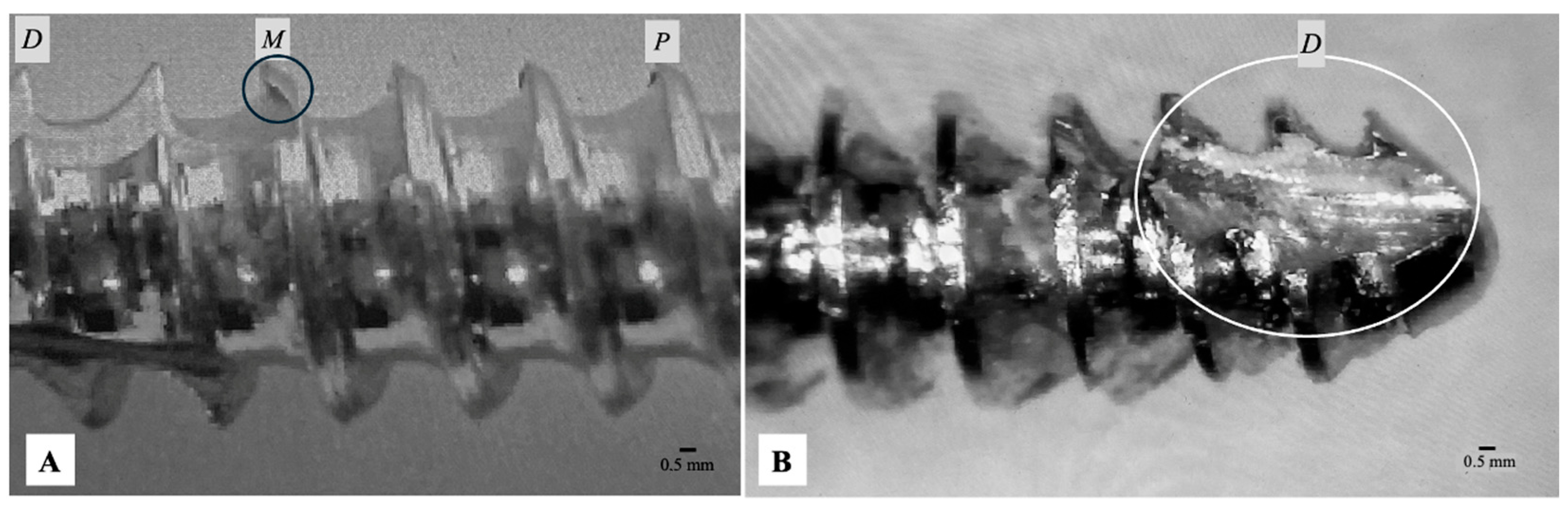

2.1. Screw Selection and Measurement Equipment

2.2. Calibration and Measurement Accuracy

2.3. Measurement Protocol

- Major (outer) diameter

- Thread pitch

2.4. Tolerance Reference

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tolerance Compliance and Detailed Dimensional Statistics

3.2. Inferential Statistical Comparisons

3.3. Operator Accuracy Variance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASTM | ASTM International |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CE | Conformité Européenne (or European Conformity) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| CV% | Coefficient of Variation |

| EDM | Electric Discharge Machining |

| EU MDR | European Union Medical Device Regulation |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| ICC | Intra-class Correlation |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| ISM | Insize Measuring (as in ISM-PM200SA microscope/software) |

| LVM | Low Vacuum Melting (as in 316LVM stainless steel) |

| mm | Millimeter |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| µm | Micrometer |

References

- Tönshoff, H.K. Basics of Cutting and Abrasive Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmac, A. Electropolishing stainless steels. Mater. Appl. Ser. 2010, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, E.F. Manufacturing of Orthopedic Plates and Screws for the Internal Fixation of Bone Fractures. Ph.D Thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.; Gupta, V.; Singh, J. Additive manufacturing-based design approaches and challenges for orthopedic bone screws: A state of the art review. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, W.; Liegey, A.; MacDonald, B.; Comiskey, D.; Galvin, E. Carbon composition analysis of 12 selected stainless steel veterinary orthopaedic implants: A preliminary report. Vet. Rec. 2013, 172, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM F86; Standard Practice for Surface Preparation and Marking of Metallic Surgical Implants. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013. Available online: http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/resolver.cgi?F86-13 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ASTM A380/A380M; Standard Practice for Cleaning, Descaling, and Passivation of Stainless Steel Parts, Equipment, and Systems. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/resolver.cgi?A380A380M-17 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ASTM A967/A967M; Standard Specification for Chemical Passivation Treatments for Stainless Steel Parts. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/resolver.cgi?A967A967M-17 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ISO/TC 150/SC 5. ISO 9585; Implants for surgery—Determination of Bending Strength and Stiffness of Bone Plates. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/17351.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ISO/TC 150/SC 5. ISO 6475; Implants for surgery—Metal Bone Screws with Asymmetrical 60° Thread and Spherical Under-Surface—Mechanical Requirements and Test Methods. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/12838.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ISO/TC 150/SC 5. ISO 5835; Implants for Surgery—Metal Bone Screws with Hexagonal Drive Connection, Spherical Under-Surface of Head, Asymmetrical Thread—Dimensions. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/12001.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ISO 19227:2018; Implants for Surgery—Cleanliness of Orthopedic Implants—General Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66817.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Zhang, Q.H.; Tan, S.H.; Chou, S.M. Investigation of fixation screw pullout strength on human spine. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausepohl, T.; Möhring, R.; Penning, D.; Koebke, J. Fine thread versus coarse thread: A comparison of the maximum holding power. Injury 2001, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, A. Computational simulations of stress shielding and bone resorption around existing and computer-designed orthopedic screws. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2002, 40, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevimay, M.; Turhan, F.; Kilicarslan, M.A.; Eskitascioglu, G. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of the effect of different bone quality on stress distribution in an implant-supported crown. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2005, 93, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, K.; Dehua, L.; Hongzhi, Z.; Ziyan, W.; Baolin, L. Selection of the implant thread pitch for optimal biomechanical properties: A three-dimensional finite element analysis. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2009, 40, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, A. Optimizing the biomechanical compatibility of orthopedic screws for bone fracture fixation. Med. Eng. Phys. 2002, 24, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidermann, W.; Gerlach, K.L.; Grobel, K.H.; Köllner, H.G. Influence of different pilot hole sizes on torque measurements and pullout analysis of osteosynthesis screws. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 26, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battula, S.; Schoenfeld, A.; Sahai, V.; Vrabec, G.; Tank, J.; Njus, G. The effect of pilot hole size on the insertion torque and pullout strength of self-tapping cortical bone screws in osteoporotic bone. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2008, 64, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.N.; Jordan, B.A. The mechanical properties of surgical bone screws and some aspects of insertion practice. Injury 1972, 4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.H.; Bell, W.H.; Schneiderman, E.D.; Ashma, B.A. Biomechanical properties of small bone screws. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 52, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleek, T.; Reynolds, K.; Hearn, T. Effect of screw torque level on cortical bone pullout strength. J. Orthop. Trauma 2007, 21, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugas, A.T.; Aloj, D.C.; Santoro, D.; Civilini, V.; Borrelli, S.; Bignardi, C. Cortical bone screws constructive characteristics—A comparative study. Int. J. Comput. Methods Exp. Meas. 2012, 9, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornetta, P.; Petteys, T.; Gerlach, D.; Cartner, J.; Walker, Z.; Russell, T. A comparison of screw insertion torque and pullout strength. J. Orthop. Trauma 2010, 24, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Tissue reaction to metals—The influence of surface finish. J. Bone Jt. Surgery. Am. Vol. 1961, 43, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, E.M.; Salaorno, M.; Grasso, G.; Audenino, A.L. Parametric analysis of orthopedic screws in relation to bone density. Open Med. Inform. J. 2009, 3, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhthoff, H.K. Mechanical factors influencing the holding power of screws in compact bone. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 1973, 55, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haje, D.P.; Volpon, J.B. Bovine bone screws development: Machining method and metrological study with profile projector. Acta Ortopédica Bras. 2006, 14, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, H.L.; Nagy, K.; Luongo, F.; Luongo, G.; Adnakin, O.; Mangano, F.G. Tolerances in the production of six different implant scan bodies: A comparative study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Screw Size | Parameter | Location | Compliance (n/N) | Compliance (%) (95% CI) | Mean (mm) | SD (mm) | CV% | Intra-Screw Variation (Out of Tolerance %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 mm | Major Diameter | Overall | 33/60 | 55% (42%, 68%) | 2.029 | 0.052 | 2.57% | 45% (27/60) |

| Proximal | 2.029 | 0.052 | 2.57% | |||||

| Middle | 2.028 | 0.057 | 2.80% | |||||

| Distal | 2.030 | 0.046 | 2.27% | |||||

| Pitch | Overall | 14/60 | 23% (13%, 36%) | 0.488 | 0.045 | 9.22% | 77% (46/60) | |

| Proximal | 0.490 | 0.046 | 9.40% | |||||

| Middle | 0.489 | 0.044 | 9.00% | |||||

| Distal | 0.485 | 0.045 | 9.29% | |||||

| 3.5 mm | Major Diameter | Overall | 33/60 | 55% (42%, 68%) | 3.571 | 0.104 | 2.91% | 45% (27/60) |

| Proximal | 3.560 | 0.106 | 2.98% | |||||

| Middle | 3.593 | 0.101 | 2.80% | |||||

| Distal | 3.561 | 0.104 | 2.91% | |||||

| Pitch | Overall | 7/60 | 12% (5%, 23%) | 1.186 | 0.146 | 12.35% | 88% (53/60) | |

| Proximal | 1.182 | 0.147 | 12.44% | |||||

| Middle | 1.189 | 0.144 | 12.14% | |||||

| Distal | 1.186 | 0.146 | 12.35% |

| Comparison Type | Test Performed | Parameter | Comparison Groups | p-Value | Conclusion/Direction of Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion Compliant (Between Screw Sizes) | Fisher’s Exact Test | Major Diameter | 2.0 mm vs. 3.5 mm | 0.999 | No significant difference in major diameter compliance between screw sizes. |

| Pitch | 2.0 mm vs. 3.5 mm | 0.045 | 2.0 mm screws show significantly higher pitch compliance than 3.5 mm screws. | ||

| Intra-Screw Variability (Major Diameter vs. Pitch) | t-test/Mann–Whitney U | Intra-Screw Range | 2.0 mm: MD vs. Pitch | <0.001 | For 2.0 mm screws, intra-screw variability (range) is significantly higher for pitch than for major diameter. |

| 3.5 mm: MD vs. Pitch | 0.003 | For 3.5 mm screws, intra-screw variability (range) is significantly higher for pitch than for major diameter. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

McCartney, W.T.; Ober, C.; Donald, B.J.M.; Yiapanis, C. Analysis of 2.0 and 3.5 mm Cortical Bone Screw Dimensions. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010038

McCartney WT, Ober C, Donald BJM, Yiapanis C. Analysis of 2.0 and 3.5 mm Cortical Bone Screw Dimensions. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCartney, William T., Ciprian Ober, Bryan J. Mac Donald, and Christos Yiapanis. 2026. "Analysis of 2.0 and 3.5 mm Cortical Bone Screw Dimensions" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010038

APA StyleMcCartney, W. T., Ober, C., Donald, B. J. M., & Yiapanis, C. (2026). Analysis of 2.0 and 3.5 mm Cortical Bone Screw Dimensions. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010038