Structural and Functional Analysis of Porcine CR1-like Proteins in C4b-Mediated Immune Responses

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Strains

2.2. Detection of Changes in Serum C4 Activity

2.3. C4b in EM Detection of RBC-PRRSV Adhesion

2.4. Pig CR1-like-C4b Domain Prediction

2.5. Construction of Recombinant Plasmid

2.6. Self-Activation Detection and Toxicity Test

2.7. Identification of CR1-like Active Fragment Combined with C4b Yeast Two-Hybrid

2.8. Homology Modeling

2.9. Molecular Docking and Kinetic Simulation

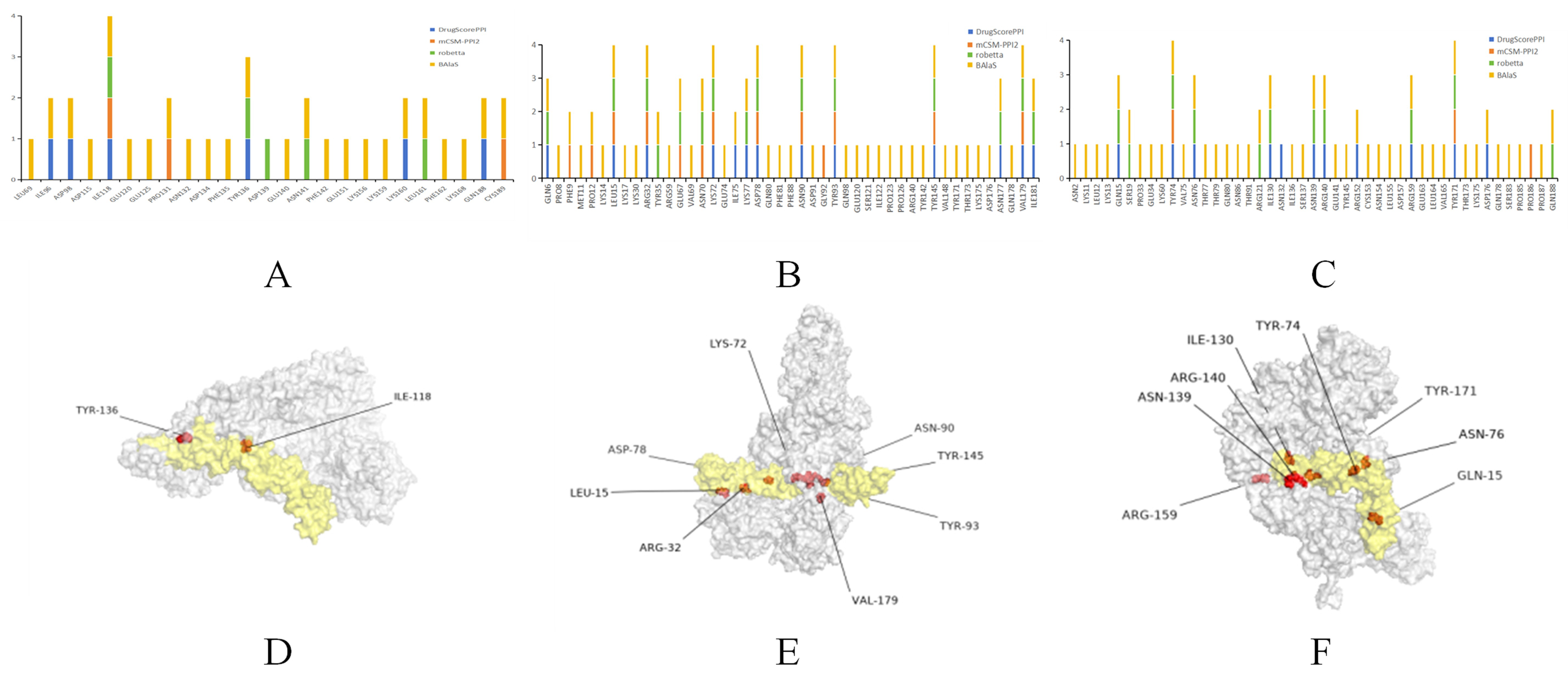

2.10. Prediction of Key Amino Acids in CR1-like-C4b Interactions

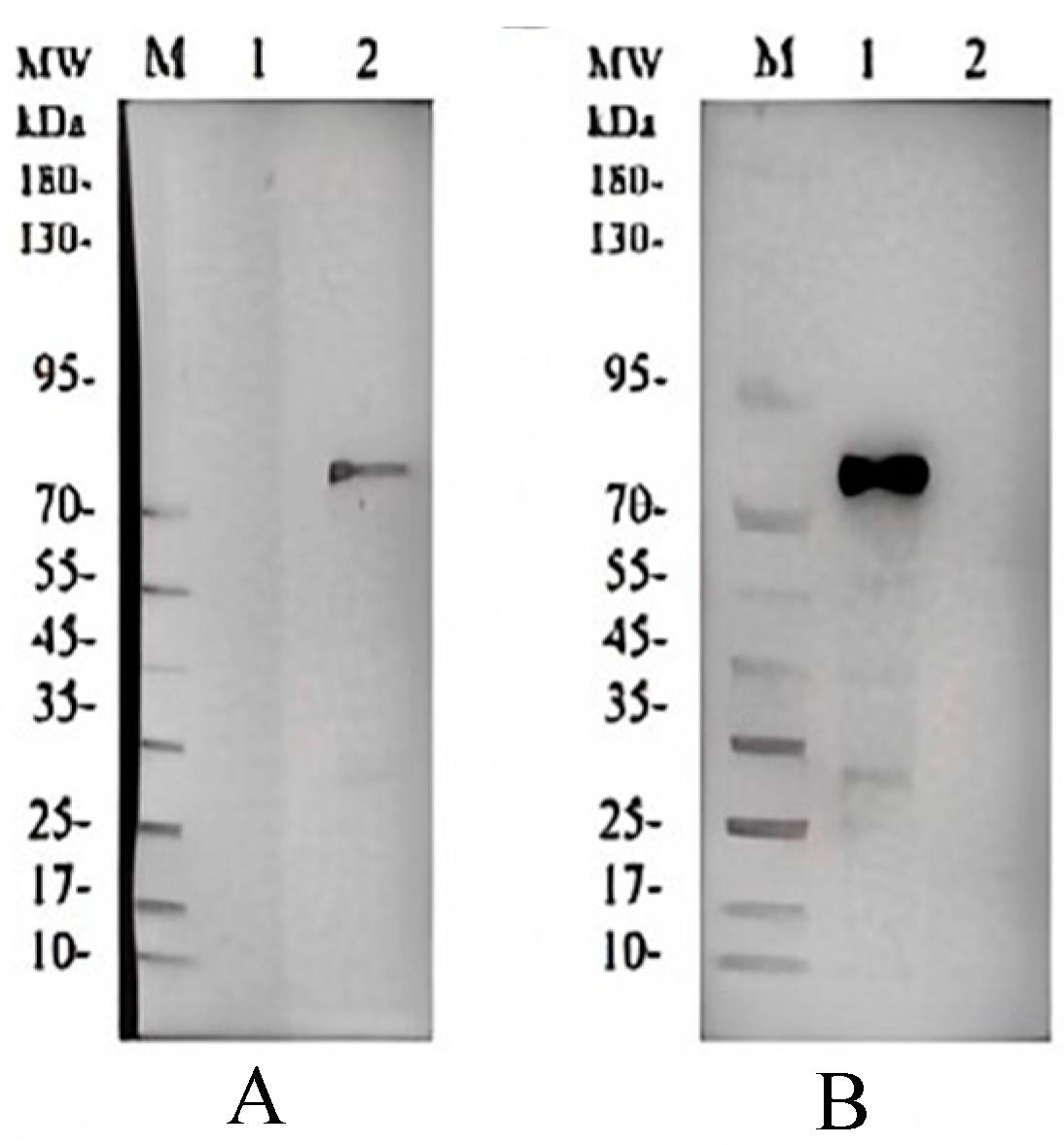

2.11. C4b Is Expressed in the Large Intestine Expression System

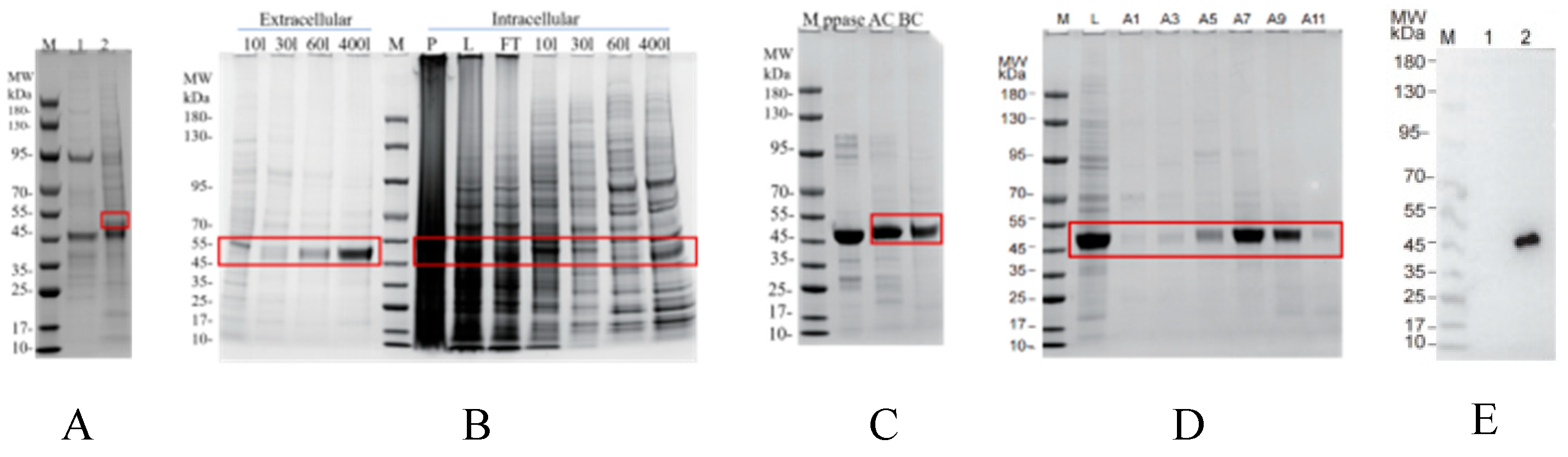

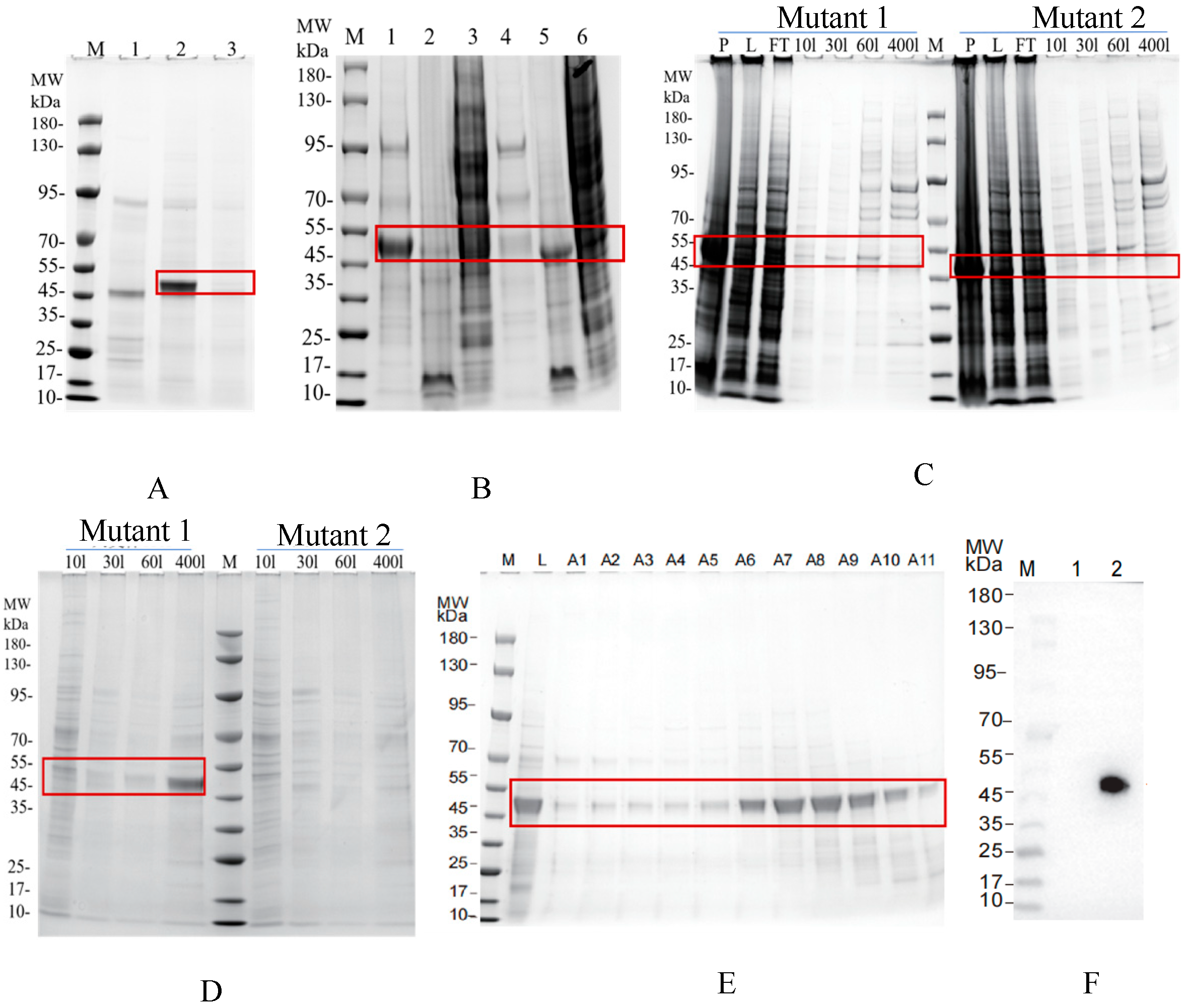

2.12. CR1-like Fragments and Their Mutants Are Expressed in Insect Cells

2.13. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Detection

3. Results

3.1. PRRSV Activates C4 and C4b Mediates RBC-PRRSV Immune Adhesion

3.2. Bioinformatics Prediction of CR1-like-C4b Interaction Domains

3.3. Yeast Two-Hybrid Validation of CR1-like-C4b Interaction

3.4. Molecular Simulation of CR1-like-C4b Interaction and Key Amino Acid Prediction

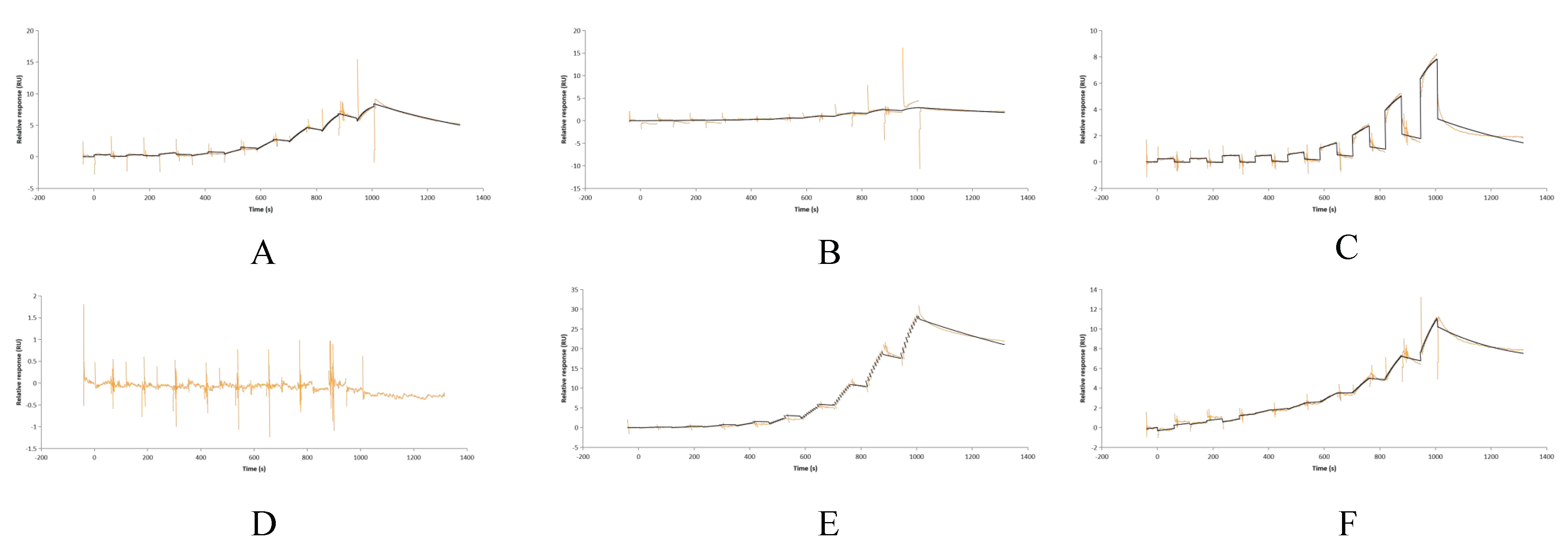

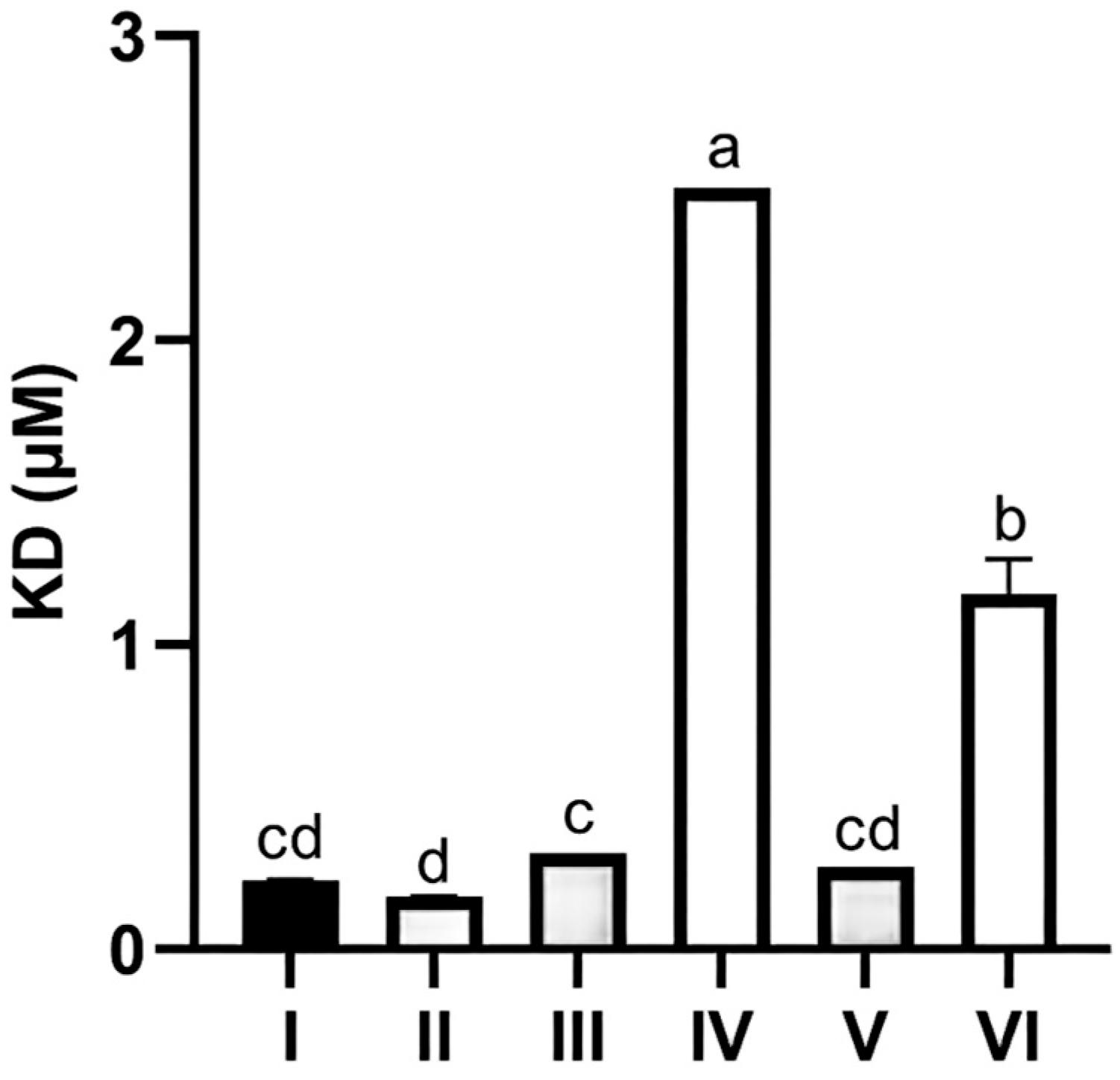

3.5. Recombinant Protein Expression and SPR Validation of CR1-like-C4b Binding Affinity

4. Discussion

4.1. Functional Mechanisms of CR1-like-C4b Interaction in Complement Regulation and Immune Adhesion

4.2. Roles of RBC-PRRSV Adhesion in PRRSV Pathogenesis and Immune Evasion

4.2.1. Facilitation of PRRSV Pathogenesis via RBC-Mediated Viral Dissemination

4.2.2. Contribution to PRRSV Immune Evasion via Antigen Masking and Complement Modulation

4.3. Technical Challenges and Optimization Strategies in Experimental Processes

4.4. Future Research Directions to Validate In Vivo Functions

4.5. Translational Implications: Therapeutic Potential Targeting the CR1-like-C4b Axis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coss, S.L.; Zhou, D.; Chua, G.T.; Aziz, R.A.; Hoffman, R.P.; Wu, Y.L.; Ardoin, S.P.; Atkinson, J.P.; Yu, C.Y. The complement system and human autoimmune diseases. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 137, 102979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallionpää, H.; Elo, L.L.; Laajala, E.; Mykkänen, J.; Ricaño-Ponce, I.; Vaarma, M.; Laajala, T.D.; Hyöty, H.; Ilonen, J.; Veijola, R.; et al. Innate immune activity is detected prior to seroconversion in children with HLA-conferred type 1 diabetes susceptibility. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2402–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.K.; Dodds, A.W. The internal thioester and the covalent binding properties of the complement proteins C3 and C4. Protein Sci. 1997, 6, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, R.B.; Sim, E. Autolytic fragmentation of complement components C3 and C4 and its relationship to covalent binding activity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1983, 421, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, R.; Mitchell, D.A.; Schmid, R.; Schwaeble, W.J.; Keeble, A.H. Paths reunited: Initiation of the classical and lectin pathways of complement activation. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilely, K.; Skjoedt, M.O.; Nielsen, C.; Andersen, T.E.; Louise Aabom, A.; Vitved, L.; Koch, C.; Skjødt, K.; Palarasah, Y. A specific assay for quantification of human C4c by use of an anti-C4c monoclonal antibody. J. Immunol. Methods 2014, 405, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilla-LaBarca, M.L.; Liszewski, M.K.; Lambris, J.D.; Hourcade, D.; Atkinson, J.P. Role of membrane cofactor protein (CD46) in regulation of C4b and C3b deposited on cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 6298–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, M.; Francisci, T.; Lackner, D.; Buerckstuemmer, T.; Wasner, K.; Eilenberg, W.; Stift, A.; Wahrmann, M.; Böhmig, G.A.; Grillari, J.; et al. CD46 knock-out using CRISPR/Cas9 editing of hTERT immortalized human cells modulates complement activation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, M. Complement C4, Infections, and Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 694928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.S.; Do, Y.; Lee, H.K.; Park, S.H.; Cheong, C.; Lynch, R.M.; Loeffler, J.M.; Steinman, R.M.; Park, C.G. A dominant complement fixation pathway for pneumococcal polysaccharides initiated by SIGN-R1 interacting with C1q. Cell 2006, 125, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammani, R.D.; Leyva, M.A.; Jennings, R.N.; Haas, K.M. C4 Deficiency is a predisposing factor for Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced autoantibody production. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 5434–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, J.A.; Blanco, E.A.; Morell, C.; Lencz, T.; Malhotra, A.K. Complement component C4 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, K.; Jiang, M.; Xie, F.; Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Yin, X. High plasma complement C4 levels as a novel predictor of clinical outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, F.; Teles, E.S.A.L.; Gomes, A.K.S.; Magdalon, J.; de Souza, J.S.; Griesi-Oliveira, K.; Passos-Bueno, M.R.; Sertié, A.L. Complement C4 Is Reduced in iPSC-Derived Astrocytes of Autism Spectrum Disorder Subjects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comer, A.L.; Jinadasa, T.; Sriram, B.; Phadke, R.A.; Kretsge, L.N.; Nguyen, T.P.H.; Antognetti, G.; Gilbert, J.P.; Lee, J.; Newmark, E.R.; et al. Increased expression of schizophrenia-associated gene C4 leads to hypoconnectivity of prefrontal cortex and reduced social interaction. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giussani, S.; Pietrocola, G.; Donnarumma, D.; Norais, N.; Speziale, P.; Fabbrini, M.; Margarit, I. The Streptococcus agalactiae complement interfering protein combines multiple complement-inhibitory mechanisms by interacting with both C4 and C3 ligands. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 4448–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovingh, E.S.; van den Broek, B.; Kuipers, B.; Pinelli, E.; Rooijakkers, S.H.M.; Jongerius, I. Acquisition of C1 inhibitor by Bordetella pertussis virulence associated gene 8 results in C2 and C4 consumption away from the bacterial surface. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottermann, M.; Foss, S.; Caddy, S.L.; Clift, D.; van Tienen, L.M.; Vaysburd, M.; Cruickshank, J.; O’Connell, K.; Clark, J.; Mayes, K.; et al. Complement C4 Prevents Viral Infection through Capsid Inactivation. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 617–629.e617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, D.T. Identification of the membrane glycoprotein that is the C3b receptor of the human erythrocyte, polymorphonuclear leukocyte, B lymphocyte, and monocyte. J. Exp. Med. 1980, 152, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, G.D.; Lambris, J.D. Identification of a C3bi-specific membrane complement receptor that is expressed on lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and erythrocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1982, 155, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricklin, D.; Hajishengallis, G.; Yang, K.; Lambris, J.D. Complement: A key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangburn, M.K. Initiation of the alternative pathway of complement and the history of “tickover”. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 313, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M.P.; Mansour, M.; Rowe, T.; Wymann, S. The Molecular Mechanisms of Complement Receptor 1-It Is Complicated. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, P.B.; Huang, C.Y.; Ihyembe, D.; Hammond, R.A.; Marsh, H.C.; Perkins, S.J. The partly folded back solution structure arrangement of the 30 SCR domains in human complement receptor type 1 (CR1) permits access to its C3b and C4b ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 375, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Niu, Z.X. The structure, genetic polymorphisms, expression and biological functions of complement receptor type 1 (CR1/CD35). Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2009, 31, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.O.; Mallin, R.L.; Krych-Goldberg, M.; Wang, X.; Hauhart, R.E.; Bromek, K.; Uhrin, D.; Atkinson, J.P.; Barlow, P.N. Structure of the C3b binding site of CR1 (CD35), the immune adherence receptor. Cell 2002, 108, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gíslason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Pedersen, M.D.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; Winther, O. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. BioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Rullmannn, J.A.; MacArthur, M.W.; Kaptein, R.; Thornton, J.M. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 1996, 8, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederstein, M.; Sippl, M.J. ProSA-web: Interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W407–W410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Yin, W.; Hao, Z.; Fan, K.; Sun, N.; Sun, P.; Li, H. Molecular Simulation Study on the Interaction between Porcine CR1-like and C3b. Molecules 2023, 28, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dauzhenka, T.; Kundrotas, P.J.; Sternberg, M.J.E.; Vakser, I.A. Application of docking methodologies to modeled proteins. Proteins 2020, 88, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.C.; Rodrigues, J.P.; Kastritis, P.L.; Bonvin, A.M.; Vangone, A. PRODIGY: A web server for predicting the binding affinity of protein-protein complexes. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3676–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, D.M.; Gohlke, H. DrugScorePPI webserver: Fast and accurate in silico alanine scanning for scoring protein-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W480–W486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.H.M.; Myung, Y.; Pires, D.E.V.; Ascher, D.B. mCSM-PPI2: Predicting the effects of mutations on protein-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W338–W344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortemme, T.; Kim, D.E.; Baker, D. Computational alanine scanning of protein-protein interfaces. Sci. STKE 2004, 2004, l2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.W.; Ibarra, A.A.; Bartlett, G.J.; Wilson, A.J.; Woolfson, D.N.; Sessions, R.B. BAlaS: Fast, interactive and accessible computational alanine-scanning using BudeAlaScan. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2917–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, A.A.; Bartlett, G.J.; Hegedüs, Z.; Dutt, S.; Hobor, F.; Horner, K.A.; Hetherington, K.; Spence, K.; Nelson, A.; Edwards, T.A.; et al. Predicting and Experimentally Validating Hot-Spot Residues at Protein-Protein Interfaces. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 2252–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bait Vector | Bait Fragment | Prey Vector | Prey Fragment | SD/-Leu Growth | SD/-Trp Growth | DDO Growth (SD/-Leu/-Trp) | DDO/X Growth (SD/-Leu/-Trp/X-α-Gal) | DDO/X/A Growth (SD/-Leu/-Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGBKT7-53 | Positive control insert | pGADT7-T | Positive control insert | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Positive control; validates assay system |

| pGBKT7-Lam | Negative control insert | pGADT7-T | Positive control insert | − | − | − | − | − | Negative control; excludes non-specific interactions |

| pGBKT7 | Empty vector | pGADT7 | Empty vector | + | + | + | + (Blue) | − | No self-activation; negative control for vectors |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 1-3 | pGADT7-C4b | α chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Vigorous growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 1-3 | pGADT7-C4b | β chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 1-3 | pGADT7-C4b | γ chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 12-14 | pGADT7-C4b | α chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 12-14 | pGADT7-C4b | β chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Vigorous growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 12-14 | pGADT7-C4b | γ chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 19-21 | pGADT7-C4b | α chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 19-21 | pGADT7-C4b | β chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

| pGBKT7-CR1-like | CCPs 19-21 | pGADT7-C4b | γ chain | + | + | + | + (Blue) | + (Blue) | Slightly weaker growth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, W.; Wang, N.; Li, J.; Yao, H.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Fan, K.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, N.; et al. Structural and Functional Analysis of Porcine CR1-like Proteins in C4b-Mediated Immune Responses. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010033

Yin W, Wang N, Li J, Yao H, Li Q, Li H, Fan K, Zhong J, Zhang Z, Sun N, et al. Structural and Functional Analysis of Porcine CR1-like Proteins in C4b-Mediated Immune Responses. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Wei, Nan Wang, Jingze Li, Haoxiang Yao, Qiongyu Li, Hongquan Li, Kuohai Fan, Jia Zhong, Zhenbiao Zhang, Na Sun, and et al. 2026. "Structural and Functional Analysis of Porcine CR1-like Proteins in C4b-Mediated Immune Responses" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010033

APA StyleYin, W., Wang, N., Li, J., Yao, H., Li, Q., Li, H., Fan, K., Zhong, J., Zhang, Z., Sun, N., Sun, P., Yang, H., Wang, J., & Sun, Y. (2026). Structural and Functional Analysis of Porcine CR1-like Proteins in C4b-Mediated Immune Responses. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010033