Suspected Japanese Pieris (Pieris japonica) Poisoning in an Alpaca (Vicugna pacos)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

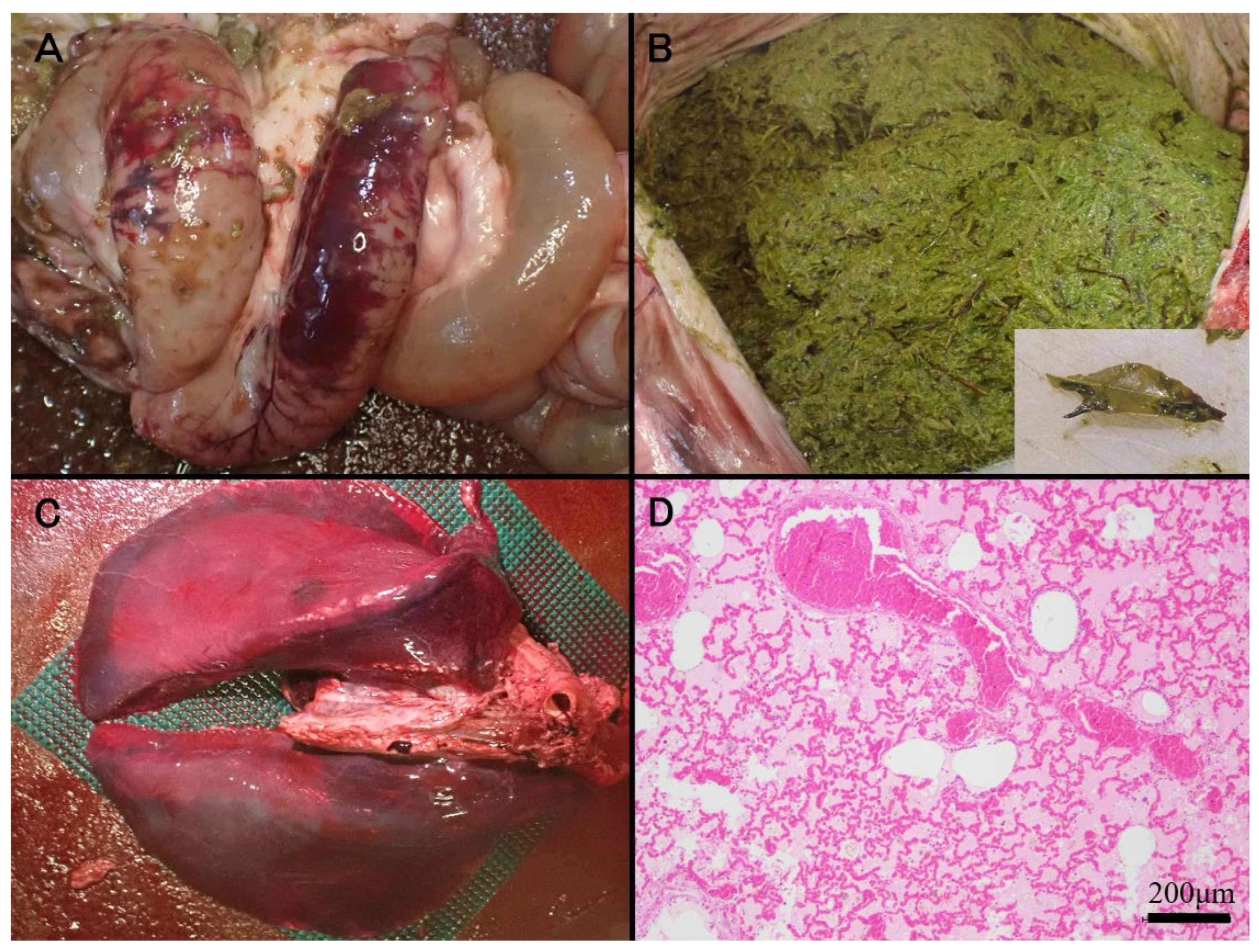

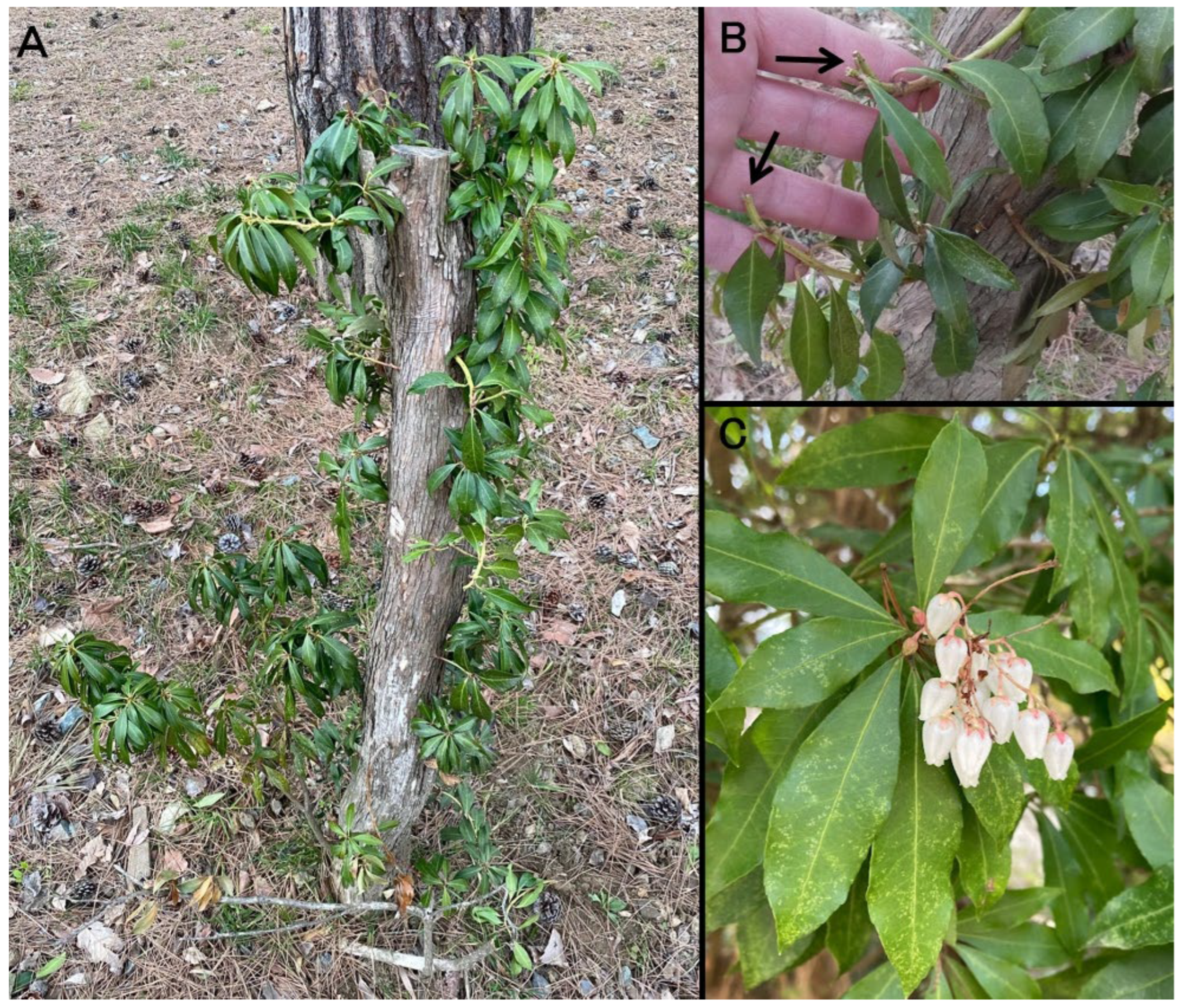

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GTXs | Grayanotoxins |

| HE | Hematoxylin-eosin |

References

- Katai, M.; Matsushima, T.; Terai, T.; Meguri, H. Studies on the constituents of the leaves of Paeris japonica D. don. IV. The isolation and the structure of pieristoxin F, pieristoxin G and several toxic components (author’s transl). Yakugaku Zasshi 1975, 95, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajito, T.; Anzai, H.; Morikawa, T.; Terui, S. A case report of Japanese Pieris poisoning in sheep. Jpn. J. Large Anim. Clin. 2001, 24, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Plumlee, K.H.; VanAlstine, W.G.; Sullivan, J.M. Japanese Pieris toxicosis of goats. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1992, 4, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puschner, B.; Holstege, D.M.; Lamberski, N. Grayanotoxin poisoning in three goats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.C. Japanese Pieris poisoning in the goat. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1978, 173, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.C. Fetal mummification in a goat due to Japanese Pieris (Pieris japonica) poisoning. Cornell Vet. 1979, 69, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Husakova, T.; Pavlata, L.; Pechova, A.; Hauptmanova, K.; Pitropovska, E.; Tichy, L. Reference values for biochemical parameters in blood serum of young and adult alpacas (Vicugna pacos). Animal 2014, 8, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, S.A.; Kleerekooper, I.; Hofman, Z.L.; Kappen, I.F.; Stary-Weinzinger, A.; van der Heyden, M.A. Grayanotoxin poisoning: ‘mad honey disease’ and beyond. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012, 12, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meguri, H. Isolation of Desacetylandromedotoxin (grayanotoxin III) and Pieristoxin C from the leaves of Pieris japonica. Yakugaku Zasshi 1959, 79, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, N. Pharmacological studies on the mechanisms of asebotoxin III-induced centrogenic pulmonary hemorrhagic edema in guinea pigs. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi 1983, 81, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikino, H.; Ohizumi, Y.; Konno, C.; Hashimoto, K.; Wakasa, H. Subchronic toxicity of ericaceous toxins and Rhododendron leaves. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeya, K.; Hotta, Y.; Harada, N.; Itoh, G.; Sakakibara, J. Asebotoxin-induced centrogenic pulmonary hemorrhage in guinea pigs. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1981, 31, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, T.; Hagiwara, A.; Nagashima, A.; Kimura, A. Case of honey intoxication in Japan. Chudoku Kenkyu. 2013, 26, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pischon, H.; Petrick, A.; Müller, M.; Köster, N.; Pietsch, J.; Mundhenk, L. Grayanotoxin I intoxication in pet pigs. Vet. Pathol. 2018, 55, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Results | Reference Ranges [7] | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit | 23 | 17.5–47.6% |

| Platelets | 91,000 | 0–387,000/mm3 |

| CK * | 15.0 | 0.6–14.7 μkat/L |

| Glucose | 362 | 45–75 mg/dL |

| Ca | 1.9 | 2.0–2.6 mmol/L |

| Sodium | 146 | 138–158 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 3 | 3.95–6.07 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 114 | 105.0–126.5 mmol/L |

| Phosphorus | 0.26 | 1.18–3.44 mmol/L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanaka, S.; Takimoto, H.; Matsubara, Y.; Tsujimoto, T.; Sasaki, J. Suspected Japanese Pieris (Pieris japonica) Poisoning in an Alpaca (Vicugna pacos). Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090806

Tanaka S, Takimoto H, Matsubara Y, Tsujimoto T, Sasaki J. Suspected Japanese Pieris (Pieris japonica) Poisoning in an Alpaca (Vicugna pacos). Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(9):806. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090806

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanaka, Saki, Haruka Takimoto, Yuki Matsubara, Tsunenori Tsujimoto, and Jun Sasaki. 2025. "Suspected Japanese Pieris (Pieris japonica) Poisoning in an Alpaca (Vicugna pacos)" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 9: 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090806

APA StyleTanaka, S., Takimoto, H., Matsubara, Y., Tsujimoto, T., & Sasaki, J. (2025). Suspected Japanese Pieris (Pieris japonica) Poisoning in an Alpaca (Vicugna pacos). Veterinary Sciences, 12(9), 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090806