1. Introduction

Pasteurization is a widely employed thermal technique in fruit juice processing, playing a crucial role in ensuring food safety, extending shelf life, and enhancing product stability. However, conventional pasteurization methods, such as conduction and convection, have notable drawbacks, including non-uniform heat distribution, extended processing times, and degradation of heat-sensitive nutrients. These limitations are particularly problematic in fruit juices, where excessive thermal exposure can lead to significant losses in vitamin C and adversely affect sensory attributes such as taste, color, and aroma, ultimately impacting consumer acceptance [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, increasing attention has been directed toward alternative heating technologies that can achieve rapid and uniform heat transfer while better preserving product quality [

4].

There are many types of pasteurization processes, and the high-temperature short-duration (HTST) method is commonly used in processing juice as it heats quickly with minimal heat damage. The high temperature and short time exposure of HTST make it possible to reduce the heat damage to heat-sensitive compounds such as vitamins, pigments, flavors, etc., which can occur with lower-temperature processing for longer times. Yet despite these benefits, HTST is still an indirect heat transfer process and can lead to uneven heat distribution and local hot-spotting, especially in viscous or particulate-containing fruit juices [

5]. Due to these drawbacks, there has been growing interest in alternative heating technologies that can offer rapid and uniform heating without compromising product quality. In this regard, ohmic heating has received attention as an alternative method of generating volumetric heat, which makes the generation and transfer of heat in the product through electrical resistance possible, thus possibly having better control over thermal treatment compared to conventional HTST systems [

6].

Ohmic heating is an advanced thermal processing method that uses electric current to generate internal heat uniformly throughout the food matrix. It offers several advantages over conventional systems, including volumetric heating, minimal surface degradation, and improved retention of color, flavor, and antioxidant content [

7]. Extensively applied in liquid and semi-liquid food systems, ohmic heating shows considerable promise for high-quality fruit juice pasteurization [

8]. A key factor influencing the efficiency of ohmic heating is the electrical conductivity (EC) of the food, which is affected by temperature, ionic concentration, viscosity, and composition [

9]. Generally, EC increases with temperature due to enhanced ion mobility and lower viscosity. Its relationship with total soluble solids (TSS) is nonlinear, as high TSS levels may reduce EC due to increased viscosity and limited free water.

The Box–Behnken design (BBD) has emerged as a robust statistical tool for optimizing processing parameters in fruit juice production. By employing three levels for each factor, BBD minimizes the number of experimental runs required while enabling comprehensive analysis of response surfaces [

10]. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated in optimizing various food processes, such as pectin extraction from fruit peels [

11] and improving fermentation conditions in functional beverages [

12]. The interpretability and efficiency of BBD make it a valuable approach for identifying optimal processing conditions that enhance product quality and sustainability in the juice industry [

13].

In addition, recent advancements in electrode plate manufacturing, low-cost optic fiber temperature sensors, and IoT-based control systems have revitalized interest in ohmic heating as a viable pasteurization method for fruit juices and liquid foods. According to Phonchan et al. [

14], the efficiency of ohmic pasteurization in maintaining the quality of passion fruit juice is mainly affected by pasteurization temperature, holding time, and voltage gradient. This agrees with the observation reported by Priyadarshini et al. [

13]. While different fruit juices, including madan juice [

15], carrot juice [

16], and mandarin juice [

17] have been studied for ohmic heating application under some pathogen periods, there is a scarcity of data on passion fruit juice, especially with respect to underlying enzyme inactivation mechanisms and quality preservation under optimized pasteurization conditions. These constitute the gaps to address to make ohmic heating a dependable and cost-effective pasteurization technology for tropical-based high-acid beverages.

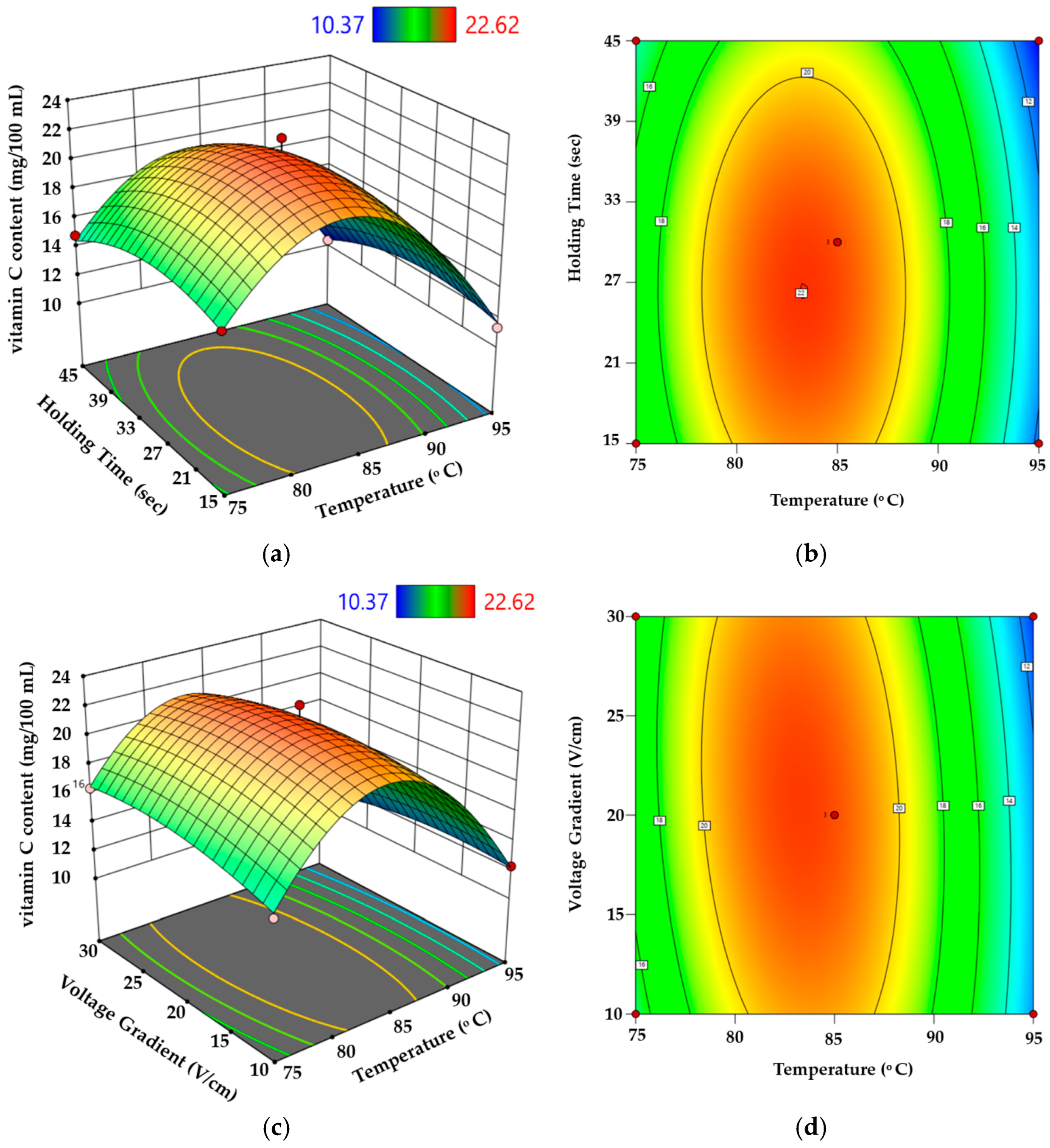

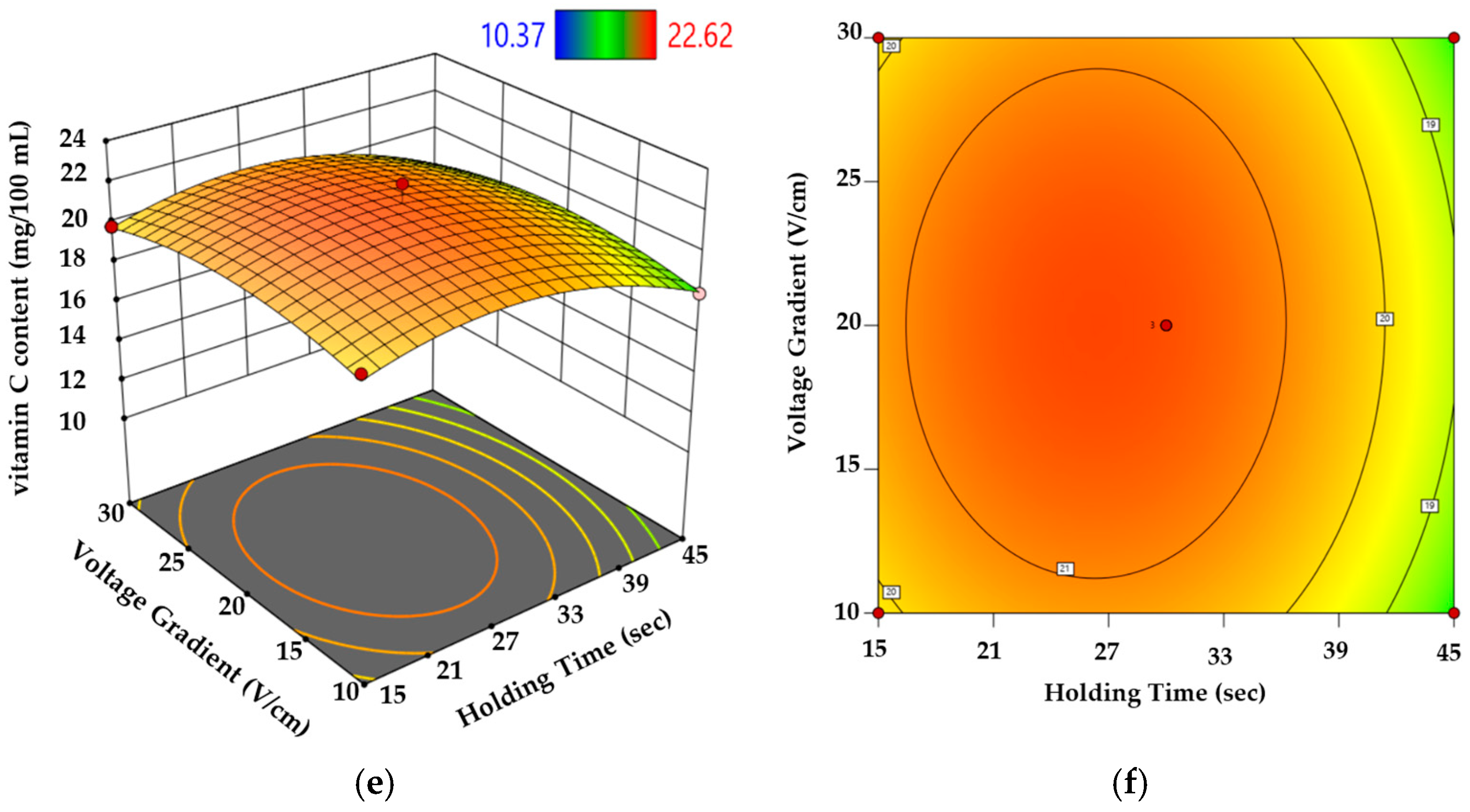

Thus, the present study was designed to explore the optimal conditions for pasteurization temperature (75, 85, and 95 °C), holding time (15, 30, and 45 s), and voltage gradient (10, 20, and 30 V/cm). According to Phonchan et al. [

14], the effectiveness of ohmic pasteurization in preserving the quality of passion fruit juice is primarily influenced by pasteurization temperature, holding time, and voltage gradient. Although ohmic heating has several advantages, limited information is available regarding its impact on fruit juice quality. Assawarachan and Tantikul [

18] investigated the electrical conductivity of passion fruit juice and reported that the highest thermal efficiency during pasteurization was achieved at a voltage gradient of 10–30 V/cm. Many RSM-based studies on ohmic heating pasteurization (OHP) have mainly focused on parameter screening or single-response optimization, with limited attention given to statistically validating optimized conditions using comparative quality indices. Consequently, quality assessment has often been conducted separately from multi-response optimization involving systematic validation. As a result, there are relatively few modeling-based studies addressing multi-response optimization of key OHP variables combined with a comprehensive evaluation of physicochemical properties, enzyme inactivation behavior, color stability, and system performance. Addressing this gap is essential for developing a reliable processing window predicted through simulation-based optimization. In this context, the present work employs a Box–Behnken design to optimize OHP conditions for passion fruit juice and to assess representative quality indices under optimized conditions in comparison with conventional thermal pasteurization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The passion fruit used in this study was developed by the Royal Project Development Center in Mae Hae, Mae Hae District, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. The fruits were harvested at the commercial ripening stage during the 2025 harvesting season (March–April). The juice was filtered and extracted using thoroughly washed fruits. Washed passion fruits were manually opened, and the pulp was separated for juice extraction. The juice was extracted with a laboratory-scale mechanical press developed by the Smart Farm Engineering and Agricultural Innovation Program, School of Renewable Energy, Maejo University, Thailand. The mechanical pressure press system accomplishes juice extraction, minimizing heat-induced quality degradation. Juice was collected and filtered on a coarse filter to separate solids prior to analysis and pasteurization. A digital refractometer (Hanna Instruments, HI 96801, Woonsocket, RI, USA) was used to measure total soluble solids (TSS), which were first registered at 11.5 °Brix.

2.2. Batch Ohmic Heating Unit for Laboratory Pasteurization

2.2.1. System Description

A laboratory-scale ohmic heating pasteurization (OHP) system was developed under the Smart Farm Engineering and Agricultural Innovation Program at the School of Renewable Energy, Maejo University, Thailand, for batch pasteurization of passion fruit juice. The system comprises a 10 L mixer tank equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a solenoid valve for flow control, and an acrylic OHP chamber (25 mm inner diameter, 10 mm length, 3 mm wall thickness). Three K-type thermocouples are strategically positioned within the chamber to monitor temperature distribution during the ohmic heating process. A programmable logic controller (Haiwell model D7-G, Xiamen, China) records real-time, current, and temperature data at 5 s intervals. After pasteurization, the treated juice flows through a cooling coil, reducing the temperature to 10 °C before being directed into the filling chamber equipped with a UV-C sterilization system. A schematic diagram of the laboratory-scale ohmic heating pasteurization system used in this study is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2.2. Experimental Operation Procedure

Before each experiment, all parts of the ohmic heating system that came into contact with food, such as the ohmic cell, pipelines, and juice containers, were sterilized in a steam autoclave (STE-18-D/E, Icanclave, Dongguan, China) at 121 °C for 15 min. This was done to ensure the system was clean and to keep experiments from mixing. The juice itself was not put through an autoclave to kill bacteria; instead, the ohmic heating process did that. The experimental operation of the laboratory-scale ohmic heating pasteurization (OHP) system was performed as follows. The passion fruit juice was added to the mixer tank and stirred mechanically to achieve a homogeneous mixture at an initial temperature of approximately 25 °C. Valve 1 was opened thereafter so that a 200 mL portion of the passion fruit juice could flow into the ohmic heating chamber (ohmic cell). The juice was then heated with the required volume up to the closed-valve level, and the juice was heated under the specified ohmic heating conditions. After heating, the valve system switched automatically to the opening position and allowed treated juice to flow through the cooling unit, where the temperature was cooled down quickly to below 10 °C. Water-ice sludge was also formed inside the bottom part of this cooler. Then, chilled juice exited from valve 3 and entered the glass bottles through the filling unit. A UV-C sterilization lamp (TUV 8W T5, Philips Lighting, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) was installed in the filling part to reduce microbial contamination of airborne particles during the packaging. All OHP lines and the process chamber were steam sterilized prior to each run to achieve sterile operation while avoiding carryover from experiment to experiment. Filled juice samples were then refrigerated at 10 °C until further physicochemical analysis. Microbial analysis was not conducted in this study and is therefore addressed as a limitation.

The ohmic heating pasteurization (OHP) principle is based on the generation of internal heat from the conversion of electrical energy, which occurs as an alternating electric current flows through the electrically conductive food matrix. The heat is produced volumetrically by Joule’s law (Q = I

2Rt, where I is the electric current, R is the electrical resistance of the product, and t is the heating time). OHP, because the heating is uniform over the entire volume, leads to lower temperature gradients and a reduced thermal inertia compared with conventional surface heating techniques. This volume heating mode can efficiently heat the product and cook it thoroughly in terms of both thermal efficiency and quality, without overcooking the surface, thereby preserving rich nutrients remaining in the bulk. In this study, to achieve uniform energy dissipation and suppress electrochemical corrosion, a low-frequency AC (50 Hz) with stainless steel electrodes was used [

13,

14,

15,

18].

2.2.3. Conventional Pasteurization (Control)

Conventional pasteurization was performed as a control treatment via a batch water bath system (Memmert GmbH + Co. KG, Schwabach, Germany). Glasses bottles were filled with passion fruit juice samples and pasteurized through immersion in a thermostatically controlled water bath at 85 ± 1 °C for 25 s, which matches the time–temperature conditions used during ohmic heating pasteurization. The juice temperature was continuously controlled with a calibrated thermometer to maintain accurate thermal input. Following pasteurization, bottles were immediately placed in an ice-water bath and quickly cooled to less than 10 °C to limit additional thermal degradation. The pasteurized samples were then stored under a refrigeration temperature (8–10 °C) before physicochemical and enzymatic analysis.

2.3. System Performance Coefficient

To assess the efficiency of the ohmic heating system, the system performance coefficient (SPC) was determined as the ratio of the sensible heat absorbed by the juice to the energy supplied to the system (1). Assuming a constant specific heat within the examined temperature range, SPC was calculated using juice mass (

m), specific heat (C

p), voltage

(V), current (

I), processing time (

t), and temperature difference (

T initial to

T final).

The specific heat capacity (

Cp) of high-moisture foods’ juice above the freezing point can be determined using the Seibel empirical formula, where

Xm denotes the moisture content of the juice [

16,

18].

where

m is the mass of juice (kg),

Cₚ is the specific heat capacity (J·kg

−1·°C

−1),

T1 and

Tf are the initial and final temperatures (°C),

V is the applied voltage (V),

I is the electric current (A), and

t is the processing time (s). The SPC is dimensionless and represents the ratio between the sensible heat absorbed by the juice and the total electrical energy supplied to the system. The moisture content (X

m) of passion fruit juice was approximately 0.88% w.b.

2.4. Optical Properties

Color was measured in reflectance mode using a Chroma Meter (CR-400, Konica Minolta Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Juice samples were placed in a standard sample cup, and color values (CIE-L*a*b*) were recorded under D65 illumination. Reflectance measurement was selected due to the turbid nature of passion fruit juice, which may interfere with transmittance-based color analysis.

The L*, a*, and b* values were measured at three different positions for each sample and averaged.

L* represents lightness,

a* indicates redness to greenness, and

b* denotes yellowness to blueness. All measurements were performed in triplicate. The total color difference (ΔE) between untreated and treated samples was calculated as follows:

where

L0*,

a0*, and

b0* refer to the values of the control or untreated sample.

2.5. Determination of Vitamin C Content

The ascorbic acid content was determined using a titrimetric method, employing 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol (DCPIP) as the oxidizing agent. The juice sample was titrated against a standardized DCPIP solution prepared from analytical-grade 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) until a persistent pink endpoint was observed. The ascorbic acid concentration was quantified by comparing the titration results with a calibration curve constructed using L-ascorbic acid as the standard [

13,

15,

17].

2.6. Enzyme Activity

Peroxidase (POD) and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity was measured spectrophotometrically to assess the stability of the enzymes post-pasteurization. Juice samples were initially centrifuged (5424 R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at 10,000×

g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used as a crude enzyme extract. The catalase activity was assayed by the change in absorbance at 470 nm due to oxidation of guaiacol in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. The reaction mixture contained phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), guaiacol solution, hydrogen peroxide, and enzyme extract. One unit of POD activity was the amount of enzyme resulting in an increase in absorbance at 470 nm per minute under assay conditions. PPO activity was expressed as the increase in absorbance at 420 because of the oxidation of catechol as the substrate. The reaction mixture consisted of phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), catechol solution, and enzyme extract. The increase in absorbance of 0.001 per minute was designated as one PPO unit. The protein content of the extract was measured by standard protein assay, and enzyme activities were reported as U·min

−1·mg

−1 protein. The remaining enzyme activity was calculated by comparison with the untreated juice, which was set at 100% [

19].

2.7. Statistical Evaluation

Design-Expert 13.0 (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to improve the response surface by applying the Box–Behnken Design (BBD) with three factors: temperature (75, 85, 95 °C), holding time (15, 30, 45 s), and voltage gradient (10, 20, 30 V/cm), leading to a total of 15 experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (p < 0.05) was used to compare ohmic and conventional pasteurization. Analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) under a Maejo University license. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

4. Discussion

The study found that OHP and conventional pasteurization affect passion fruit juice quality differently. Physicochemical characteristics, enzyme activities, color stability, and vitamin C retention between conventional pasteurization and alternative processing methods vary due to different mechanisms of heat treatment. It is interesting to note the lower pH in OHP-treated juice when compared with pasteurization. The pH reduction could be due to the physicochemical phenomenon of Ohmic heating, which may increase structural mobility of ions and/or modify dissociation equilibria under the influence of an electric field. Similar pH changes have been observed in other ohmic heating studies, showing trends consistent with the process used instead of formulation differences. Both pasteurization processes caused a slight increase in TSS, but this increment was not statistically different. This gain is known to be the result of water loss under heating, a phenomenon observed also in other thermally treated fruit juices. Little deviation from the average confirms that ohmic heating did not affect soluble solids content when compared with conventional pasteurization under present conditions. Color maintenance is of importance for fruit juices, since it decays through pigment breakdown reactions and non-enzymatic browning. Lower ΔE for OHP-treated juice reflects a lower extent of color change compared to heat-processed juice. Advantages of ohmic heating include rapid and uniform bulk heating that may mitigate local overheating and thermal impairment to thermosensitive pigments.

Vitamin C, a volatile compound sensitive to heat and oxidation, is a common nutritional indicator in fruit juices. Experiments found that OHP-treated juice preserved more vitamin C than conventional pasteurization due to its shorter heating time. As both forms of ascorbic acid are stable, the time and temperature required for thermal oxidation must be reduced. Fast target temperatures are employed to reduce exposure times at elevated temperatures, which would otherwise increase the generator formation of dehydroascorbic acid by thermal oxidation of ascorbic acid. Lower oxidative enzyme activity may also contribute to enhanced vitamin C protection in OHP. Peroxidase (POD) and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity, measured by the POD-POD-TMB assay, and the reaction rate constant revealed that OHP significantly inactivated these enzymes compared to thermal pasteurization. POD, a thermally stable heme-protein enzyme model, denatures by breaking H-bonds and altering tertiary structure at high temperatures. Rapid volumetric heating and electric fields can accelerate structural changes during ohmic heating, leading to increased enzyme inactivation. Chemical stress has been suggested for PPO, which is also affected by thermal and electrical stress. The system performance coefficient (SPC) of OHP-treated juice was higher than that for fresh juices, showing a change in efficiency produced with ohmic heating. The conversion of electric energy into thermal energy in the product matrix lowers heat-transfer resistance and increases processing efficiency. In general, quality parameters, including color, vitamin C content, and enzyme stability of passion fruit juice, are well maintained during ohmic pasteurization compared with conventional thermal treatment. These results indicate that ohmic-heating technology can be considered as an alternative pasteurization method for fruit juice to ensure its quality.

5. Limitations

This research was performed in a controlled environment using a laboratory-scale batch ohmic heating pasteurization system. As such, the data presented may not entirely reflect performance in continuous or industrialized systems where key features such as flow dynamics, electrode design, and heat losses may vary. Furthermore, the optimization and quality assessment were only conducted for a single high-acid fruit juice (passion fruit juice) within a nominated range of total soluble solids, potentially limiting direct extrapolation to other juice matrices with different compositional or viscosity characteristics. In addition, our study mainly concentrated on the physico-chemical properties, enzyme deactivation, and system performance coefficient. However, the kinetics of microbial inactivation and its shelf-life stability during longer periods of storage have not been studied, which will ultimately better characterize the industrial potential for improved ohmic heating pasteurization conditions.