Caffeine Consumption and Risk Assessment Among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

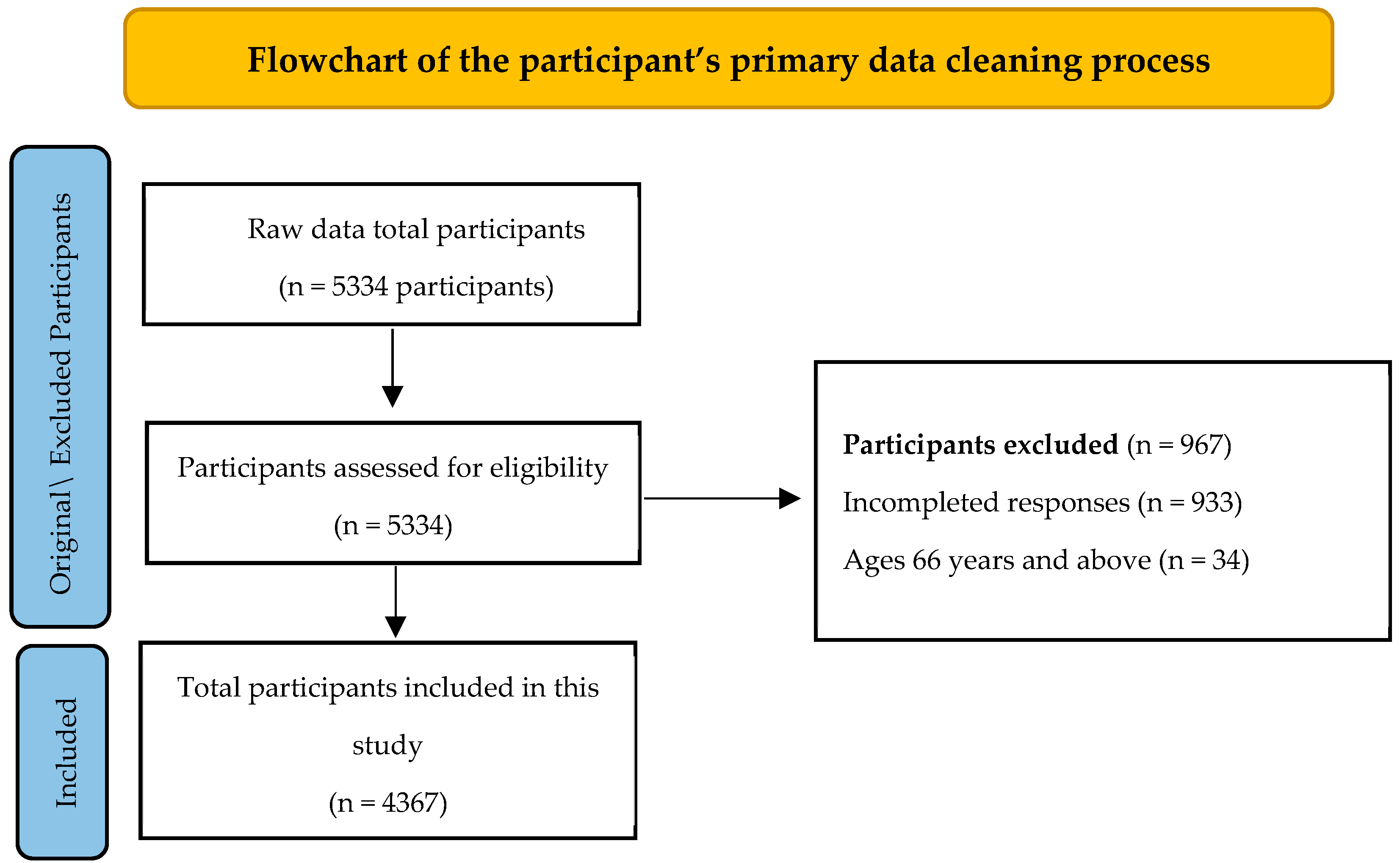

2.2. Sample/Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Caffeinated Beverage Consumption Data

2.3.2. Caffeine Concentration in Caffeinated Beverages

2.3.3. Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) of Caffeine

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Tested Group

3.2. Pattern of Caffeinated Beverage Consumption

3.3. Caffeine Intake

3.4. Risk Assessment of Caffeine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disclosure Statement

References

- Lambrych, M. Caffeine. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 417–425. ISBN 9780128243152. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, M.A.; Weil, J.; de Mejia, E.G. Caffeine (1, 3, 7-Trimethylxanthine) in Foods: A Comprehensive Review on Consumption, Functionality, Safety, and Regulatory Matters. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, R77–R87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Why Did EFSA Carry out Its Risk Assessment? EFSA: Parma, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, I.; Cellai, L.; Meriaux, C.; Poncelet, L.; Nebie, O.; Saliou, J.M.; Lacoste, A.S.; Papegaey, A.; Drobecq, H.; Le Gras, S.; et al. Caffeine Intake Exerts Dual Genome-Wide Effects on Hippocampal Metabolism and Learning-Dependent Transcription. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e149371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, F.; Stampfer, M.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Trudel-Fitzgerald, C. Prospective Associations between Coffee Consumption and Psychological Well-Being. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadra, G.R.; Paranaíba, J.R.; Vilas-Boas, J.; Roland, F.; Amado, A.M.; Barros, N.; Dias, R.J.P.; Cardoso, S.J. A Global Trend of Caffeine Consumption over Time and Related-Environmental Impacts. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Keast, D.R.; Lieberman, H.R. Trends in Intake and Sources of Caffeine in the Diets of US Adults: 2001–2010. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verster, J.C.; Koenig, J. Caffeine Intake and Its Sources: A Review of National Representative Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, J. Neurologic Effects of Caffeine Physiologic Effects of Caffeine. Medscape Ref. Drug Dis. Proced. 2015, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Radwan, R.A.; Alwafi, H.H.; Alhindi, Y.Z.; Falemban, A.H.; Ansari, S.A.; Alshanberi, A.M.; Ayoub, N.A.; Alsanosi, S.M. Patterns of Caffeine Consumption in Western Province of Saudi Arabia. Pharmacogn. Res. 2022, 14, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rara, R.; Alhindi, R.; Alotaibi, M.; Shaykhayn, Y.; Alnakhli, A.; Albar, H.T.; Alshanberi, A.M.; Alhindi, Y.Z.; Alsanosi, S.M. The Use of Caffeine Products in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacogn. Res. 2023, 15, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadh, R.A.; Abid, N.; Alsaad, A.S.; Aljohar, H.I.; Alharbi, M.M.; Alhussain, F.K. Arabic Coffee Consumption and Its Correlation to Obesity Among the General Population in the Eastern Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e30848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodak, K.; Kokot, I.; Kratz, E.M. Caffeine as a Factor Influencing the Functioning of the Human Body—Friend or Foe? Nutrients 2021, 13, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikoff, D.; Welsh, B.T.; Henderson, R.; Brorby, G.P.; Britt, J.; Myers, E.; Goldberger, J.; Lieberman, H.R.; O’Brien, C.; Peck, J.; et al. Systematic Review of the Potential Adverse Effects of Caffeine Consumption in Healthy Adults, Pregnant Women, Adolescents, and Children. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 585–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostoni, C.; Berni Canani, R.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Korhonen, H.; La Vieille, S.; Marchelli, R.; Martin, A.; Naska, A.; Neuhäuser-Berthold, M.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the Safety of Caffeine. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.R.; Cunha, R.A. Impact of Coffee Intake on Human Aging: Epidemiology and Cellular Mechanisms. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 102, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhirgham, T.M.; Almutairi, L.A.; Alraqea, A.S.; Alqahtani, A.S. Online Arabic Beverage Frequency Questionnaire (ABFQ): Evaluation of Validity and Reliability. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHA. Food Labeling Company-Nutrition & Supplement Software. Available online: https://esha.com/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Aldhirgham, T.; Alammari, N.; Aljameel, G.M.; Alzuwaydi, A.; Almasoud, S.A.; Alawwad, S.A.; Alabbas, N.H.; Alqahtani, A.S. The Saudi Branded Food Database: First-Phase Development (Branded Beverage Database). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 120, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltyeb, E.E.; Al-Makramani, A.A.; Mustafa, M.M.; Shubayli, S.M.; Madkhali, K.A.; Zaalah, S.A.; Ghalibi, A.T.; Ali, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Basheer, R.A. Caffeine Consumption and Its Potential Health Effects on Saudi Adolescents in Jazan. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albar, S.A.; Almaghrabi, M.A.; Bukhari, R.A.; Alghanmi, R.H.; Althaiban, M.A.; Yaghmour, K.A. Caffeine Sources and Consumption among Saudi Adults Living with Diabetes and Its Potential Effect on HbA1c. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlawi, M.; Hennawi, Y.B.; Baharith, M.; Almurakshi, M.; Bawashkhah, A.; Dahlawi, S.; Alosaimi, S.B.; Alnahdi, F.S.; Alessa, T.T.; Althobity, O.; et al. The Association Between Caffeine Consumption and Academic Success in Makkah Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e57975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljaadi, A.M.; Turki, A.; Gazzaz, A.Z.; Al-Qahtani, F.S.; Althumiri, N.A.; BinDhim, N.F. Soft and Energy Drinks Consumption and Associated Factors in Saudi Adults: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1286633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analytica, A. Saudi Arabia Soft Drinks Market to Hit Valuation of USD 18.1 Billion by 2032|Astute Analytica. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/saudi-arabia-soft-drinks-market-143000888.html?guccounter=1 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Mitchell, D.C.; Knight, C.A.; Hockenberry, J.; Teplansky, R.; Hartman, T.J. Beverage Caffeine Intakes in the U.S. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 63, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Xiao, X.; Sui, H.; Yang, D.; Yong, L.; Song, Y. Trends of Caffeine Intake from Food and Beverage among Chinese Adults: 2004–2018. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 173, 113629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, C.; Eap, C.B.; Bochud, M.; Chatelan, A. Caffeine Consumption in Switzerland: Results from the First National Nutrition Survey MenuCH. Nutrients 2019, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.S.; Hwang, J.Y.; Choi, J.C.; Kim, M. Assessment of Caffeine Intake in the Korean Population. Food Addit. Contam. Part A. Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2015, 32, 1786–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, D.; Lau, A.; Richardson, P.; Roberts, A. Temporal Patterns of Caffeine Intake in the United States. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 111, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni, V.L. Daily Patterns of Caffeine Intake and the Association of Intake with Multiple Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors in US Adults Based on the NHANES 2007–2012 Surveys. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, J.J.; Whiting, S.H.; Encarnação, R.; Norberg, S.; Jones, R.; Reinap, M.; Jewell, J. Energy Drink Consumption in Europe: A Review of the Risks, Adverse Health Effects, and Policy Options to Respond. Front. Public Heal. 2014, 2, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torpy, J.M.; Livingston, E.H. Energy Drinks. JAMA 2013, 309, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsunni, A.A. Energy Drink Consumption: Beneficial and Adverse Health Effects. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 2015, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFDA. Energy Drink Requirements; SFDA: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- SFDA. SFDA: Consuming Large Amounts of Caffeine After Iftar Has Negative Effects. Available online: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/news/88053 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- SFDA Caffeine Calculator. Available online: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/body-calculators/caffeine-calculator (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Yang, A.; Palmer, A.A.; De Wit, H. Genetics of Caffeine Consumption and Responses to Caffeine. Psychopharmacology 2010, 211, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, M.C.; El-Sohemy, A.; Campos, H. Genetic Polymorphism of the Adenosine A2A Receptor Is Associated with Habitual Caffeine Consumption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehlig, A. Interindividual Differences in Caffeine Metabolism and Factors Driving Caffeine Consumption. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 384–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOH Women’s Health-Caffeine and Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/wh/Pages/035.aspx (accessed on 2 October 2024).

| Beverage Category | Caffeine Concentration (mg/100 mL) |

|---|---|

| Soft drinks | 10.24 |

| Sugar-free soft drinks | 10.24 |

| Iced tea | 75.47 |

| Sugar-free tea | 20.02 |

| Sugar and milk tea | 20.02 |

| Saudi coffee with milk | 35.69 |

| Saudi coffee without milk | 40.04 |

| Sugar-free Turkish or espresso coffee | 38.78 |

| Sweetened Turkish or espresso coffee | 26.21 |

| Sugar-free black coffee | 40.04 |

| Sweetened black coffee | 36.69 |

| Flavored coffee | 37.73 |

| Sugar-free energy drinks | 32.00 |

| Sweetened energy drinks | 25.43 |

| Sports drinks | 32.00 |

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1970 | 45 |

| Female | 2397 | 56 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 1340 | 30.7 |

| 30–44 | 2042 | 46.8 |

| 45–59 | 911 | 20.9 |

| +60 | 74 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 2747 | 62.9 |

| Single | 1376 | 31.5 |

| Divorced/widow | 22 | 5.6 |

| Pregnant/breastfeeding women | 244 | 5.6 |

| Region | ||

| Riyadh | 485 | 11.1 |

| Madinah | 480 | 11 |

| Albaha | 398 | 9.1 |

| Aseer | 363 | 8.3 |

| Makkah | 351 | 8 |

| Eastern Province | 325 | 7.4 |

| Najran | 311 | 7.1 |

| Hail | 301 | 7 |

| Jazan | 307 | 7 |

| Tabuk | 306 | 7 |

| Aljouf | 291 | 6.7 |

| AlQassim | 262 | 6 |

| Northern Border | 187 | 4.3 |

| Variable (Min–Max) | Mean ± SE | Median |

| Age (18–65 years) | 35 ± 0.16 | 36 |

| Weight (40–187 kg) | 73 ± 0.27 | 71 |

| Beverages | Overall Consumption N (%) | Pattern of Consumption | Overall n | Gender | Age Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–59 | +60 | |||||

| 1 | Saudi coffee | 3454 (79) | Never | 913 | 399 | 514 | 362 | 409 | 130 | 12 |

| Daily | 1730 | 772 | 958 | 357 | 840 | 473 | 42 | |||

| Weekly | 1080 | 496 | 584 | 373 | 506 | 188 | 13 | |||

| Monthly | 644 | 303 | 341 | 230 | 287 | 120 | 7 | |||

| 2 | Soft drinks | 3274 (75) | Never | 1093 | 501 | 592 | 268 | 508 | 282 | 35 |

| Daily | 657 | 367 | 290 | 267 | 314 | 73 | 3 | |||

| Weekly | 1238 | 568 | 670 | 446 | 580 | 200 | 12 | |||

| Monthly | 1379 | 534 | 845 | 359 | 640 | 356 | 24 | |||

| 3 | Sweetened tea | 3026 (69.30) | Never | 1341 | 563 | 778 | 410 | 599 | 296 | 36 |

| Daily | 1314 | 695 | 619 | 305 | 678 | 309 | 22 | |||

| Weekly | 982 | 417 | 565 | 373 | 433 | 166 | 10 | |||

| Monthly | 730 | 295 | 435 | 258 | 332 | 140 | 6 | |||

| 4 | Unsweetened tea | 2147 (49.16) | Never | 2220 | 957 | 1245 | 847 | 1006 | 366 | 24 |

| Daily | 746 | 374 | 372 | 119 | 351 | 252 | 24 | |||

| Weekly | 743 | 332 | 411 | 193 | 376 | 156 | 18 | |||

| Monthly | 658 | 289 | 269 | 204 | 309 | 137 | 8 | |||

| 5 | Flavored coffee with milk | 2104 (48.18) | Never | 2263 | 1169 | 1094 | 620 | 1025 | 565 | 53 |

| Daily | 248 | 93 | 155 | 74 | 132 | 38 | 4 | |||

| Weekly | 655 | 249 | 406 | 241 | 309 | 102 | 3 | |||

| Monthly | 1201 | 459 | 742 | 405 | 576 | 206 | 14 | |||

| 6 | Unsweetened Turkish coffee or espresso | 1873 (42.88) | Never | 2494 | 1062 | 1432 | 836 | 1081 | 528 | 49 |

| Daily | 537 | 263 | 274 | 122 | 290 | 114 | 11 | |||

| Weekly | 603 | 294 | 309 | 167 | 328 | 103 | 5 | |||

| Monthly | 733 | 351 | 382 | 215 | 343 | 166 | 9 | |||

| 7 | Unsweetened black or filtered coffee | 1850 (42.3) | Never | 2517 | 1055 | 1462 | 646 | 1154 | 654 | 63 |

| Daily | 595 | 311 | 284 | 217 | 279 | 79 | 2 | |||

| Weekly | 622 | 308 | 314 | 243 | 309 | 67 | 3 | |||

| Monthly | 633 | 296 | 337 | 234 | 282 | 111 | 6 | |||

| 8 | Diet soft drinks | 1479 (33.86) | Never | 2888 | 1236 | 1652 | 861 | 1310 | 660 | 57 |

| Daily | 208 | 120 | 88 | 65 | 121 | 20 | 2 | |||

| Weekly | 482 | 257 | 225 | 166 | 256 | 57 | 3 | |||

| Monthly | 789 | 357 | 432 | 248 | 355 | 174 | 12 | |||

| 9 | Saudi coffee with milk | 1363 (31.2) | Never | 3004 | 1417 | 1587 | 921 | 1367 | 660 | 56 |

| Daily | 486 | 173 | 313 | 129 | 257 | 89 | 11 | |||

| Weekly | 476 | 193 | 283 | 159 | 231 | 83 | 3 | |||

| Monthly | 401 | 187 | 214 | 131 | 187 | 79 | 4 | |||

| 10 | Sweetened energy drink | 1033 (23.65) | Never | 3334 | 1399 | 1935 | 888 | 1568 | 807 | 71 |

| Daily | 139 | 71 | 68 | 55 | 68 | 15 | 1 | |||

| Weekly | 300 | 177 | 123 | 129 | 140 | 31 | 0 | |||

| Monthly | 594 | 323 | 271 | 268 | 266 | 58 | 2 | |||

| 11 | Sweetened Turkish coffee or espresso | 1061 (24.3) | Never | 3306 | 1468 | 1838 | 1060 | 1504 | 679 | 63 |

| Daily | 230 | 105 | 125 | 50 | 122 | 56 | 2 | |||

| Weekly | 304 | 141 | 163 | 73 | 170 | 59 | 2 | |||

| Monthly | 527 | 256 | 271 | 157 | 246 | 117 | 7 | |||

| 12 | Iced tea | 1025 (23.47) | Never | 3342 | 1537 | 1805 | 874 | 1598 | 804 | 66 |

| Daily | 133 | 56 | 77 | 52 | 66 | 13 | 2 | |||

| Weekly | 342 | 144 | 198 | 156 | 156 | 28 | 2 | |||

| Monthly | 650 | 233 | 317 | 258 | 222 | 66 | 4 | |||

| 13 | Black or filtered coffee with milk | 794 (18.18) | Never | 3573 | 1633 | 1940 | 1058 | 1648 | 797 | 70 |

| Daily | 147 | 67 | 80 | 56 | 73 | 18 | 0 | |||

| Weekly | 284 | 112 | 172 | 94 | 156 | 32 | 2 | |||

| Monthly | 363 | 158 | 205 | 132 | 165 | 64 | 2 | |||

| 14 | Diet energy drink | 495 (11.33) | Never | 3872 | 1701 | 2171 | 1164 | 1790 | 847 | 71 |

| Daily | 83 | 47 | 36 | 29 | 40 | 13 | 1 | |||

| Weekly | 161 | 88 | 73 | 54 | 90 | 16 | 1 | |||

| Monthly | 251 | 134 | 117 | 93 | 122 | 35 | 1 | |||

| 15 | Sport drink | 356 (8.15) | Never | 4011 | 1791 | 2220 | 1224 | 1849 | 867 | 71 |

| Daily | 66 | 35 | 31 | 20 | 38 | 7 | 1 | |||

| Weekly | 138 | 68 | 70 | 39 | 77 | 20 | 2 | |||

| Monthly | 152 | 76 | 76 | 57 | 78 | 17 | 0 | |||

| N (%) | Mean ± SE | Median, IQR (25–75) | p Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.000 | |||

| Male | 1970 (45) | 145 ± 2.3 | 120 (71–169) | |

| Female | 2397 (56) | 120 ± 1.8 | 104 (51–158) | |

| Region | 0.021 | |||

| Riyadh | 485 (11.1) | 146 ± 4.7 | 120 (70–195) | |

| Madinah | 480 (11) | 126 ± 4.4 | 112 (49–170) | |

| Albaha | 398 (9.1) | 120 ± 4.8 | 103 (44–158) | |

| Aseer | 363 (8.3) | 120 ± 4.7 | 108 (53–168) | |

| Makkah | 351 (8) | 127 ± 5.4 | 101 (50–175) | |

| Eastern Province | 325 (7.4) | 133 ± 5.6 | 166 (57–181) | |

| Hail | 301 (7) | 141 ± 5.3 | 120 (74–193) | |

| Jazan | 307 (7) | 129 ± 5.6 | 120 (58–126) | |

| Tabuk | 306 (7) | 137 ± 5.6 | 120 (63–182) | |

| Aljouf | 291 (6.7) | 144 ± 5.4 | 120 (86–188) | |

| AlQassim | 262 (6) | 139 ± 5.6 | 120 (73–185) | |

| Northern Border | 187 (4.3) | 126 ± 7.1 | 113 (47–182) | |

| Najran | 311 (7.1) | 120 ± 5.3 | 101 (54–155) | |

| Age | 0.174 | |||

| 18–29 | 1340 (30.7) | 135 ± 2.74 | 120 (56.7–182.9) | |

| 30–44 | 2042 (46.8) | 134 ± 2.19 | 120 (61.7–177.5) | |

| 45–59 | 911 (20.9) | 121.9 ± 2.9 | 104 (53–164) | |

| +60 | 74 (1) | 121 ± 10 | 101 (62–155) | |

| Pregnant/breastfeeding women | 244 (5.6) | 105 ± 5.2 | 98.9 (41–125) | - |

| Beverage Category | Total Consumption for Each Category | Caffeine Intake (mg/day) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean ± SE | ||

| 1 | Saudi Coffee | 3454 (79) | 140 ± 1.6 |

| 2 | Soft Drink | 3274 (75) | 136 ± 1.68 |

| 3 | Sweetened Tea | 3026 (69.30) | 137 ± 1.7 |

| 4 | Unsweetened Tea | 2147 (49.16) | 142 ± 2.1 |

| 5 | Flavored Coffee with Milk | 2104 (48.18) | 144 ± 2 |

| 6 | Turkish or Espresso without Sugar | 1873 (42.88) | 153 ± 2.32 |

| 7 | Black or Filtered Coffee | 1850 (42.3) | 169 ± 2.3 |

| 8 | Diet Soft Drink | 1479 (33.86) | 150 ± 2.67 |

| 9 | Saudi Coffee with Additives | 1363 (31.2) | 141 ± 2.5 |

| 10 | Sweetened Energy Drinks | 1033 (23.65) | 165 ± 3.2 |

| 11 | Turkish Coffee or Espresso with Sugar | 1061 (24.3) | 151 ± 3 |

| 12 | Iced Tea | 1025 (23.47) | 163 ± 3.1 |

| 13 | Black or Filtered Coffee with Milk | 794 (18.18) | 164 ± 3.6 |

| 14 | Diet Energy Drinks | 495 (11.33) | 169 ± 4.9 |

| 15 | Sport Drinks | 356 (8.15) | 169 ± 5.6 |

| Age Group (Years) | Sample n (%) | Gender | Caffeine Intake (mg/day) | HQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean ± SE (Min–Max) | Mean | 95% | |||

| 18–29 | 1340 (30.7) | 135 ± 2.74 (0–451) | 0.33 | 0.34 | ||

| Male | 478 (35.7) | 145 ± 4.79 (0–445) | 0.36 | 0.38 | ||

| Female | 862 (64.3) | 124 ± 3.28 (0–451) | 0.30 | 0.32 | ||

| 30–44 | 2042 (46.8) | 134 ± 2.19 (0–456) | 0.33 | 0.34 | ||

| Male | 991 (48.5) | 149 ± 3.3 (0–454) | 0.37 | 0.38 | ||

| Female | 1051 (51.5) | 120 ± 2.8 (0–456) | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||

| 45–59 | 911 (20.9) | 121.9 ± 2.9 (0–453) | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||

| Male | 455 (49.9) | 130 ± 4.4 (0–453) | 0.32 | 0.34 | ||

| Female | 456 (50.1) | 113 ± 3.9 (0–448) | 0.28 | 0.29 | ||

| +60 | 74 (1) | 121 ± 10 (0–414) | 0.30 | 0.34 | ||

| Male | 46 (62.2) | 129 ± 12.7 (0–392) | 0.32 | 0.37 | ||

| Female | 28 (37.8) | 108 ± 16 (0–414) | 0.27 | 0.33 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almutairi, L.A.; Alsayari, A.A.; Alqahtani, A.S. Caffeine Consumption and Risk Assessment Among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Beverages 2025, 11, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040123

Almutairi LA, Alsayari AA, Alqahtani AS. Caffeine Consumption and Risk Assessment Among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Beverages. 2025; 11(4):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040123

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmutairi, Lulu A., Abdullah A. Alsayari, and Amani S. Alqahtani. 2025. "Caffeine Consumption and Risk Assessment Among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Beverages 11, no. 4: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040123

APA StyleAlmutairi, L. A., Alsayari, A. A., & Alqahtani, A. S. (2025). Caffeine Consumption and Risk Assessment Among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Beverages, 11(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040123