Nano-Modeling and Computation in Bio and Brain Dynamics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Nanoscience in the Brain

- (1)

- Snapshots of connections in the brain by making thin physical slices and stacking electron microscopy images (this technique does not provide dynamic and chemical information);

- (2)

- (3)

- The attempt to obtain functional chemical maps of the neurotransmitter systems in the brain, for investigating the genetic and chemical brain heterogeneity and the interactions among neurotransmitter systems.

3. Transport Processes at Nano-Level: Technical Details

- (a)

- The velocities correlation function of a system at the temperature T, from which it is possible to obtain the velocity of a carrier at generic time t;

- (b)

- The mean squared deviation of position R2(t), defined as , from which the position of a carrier in time is obtainable;

- (c)

4. Examples of Application and Results

- (a)

- An inertial system is used to describe the ordinary differential equation (ODE) types based on standard physical terminology, which is well defined. An example of non-trivial inertial system is the geodesic (kinetic energy) for a mechanical rotatory system with the inertial moment Ii,j. In this case, the geodesic is non-inertial, with an invariant given by the respective computable geodesic.

- (b)

- To take into account a minimum of biological plausibility, it is necessary to introduce a simplified membrane model. In a toy membrane just having, for example, three potassium channels (twelve gates), nine open gates can be configured into a variety of topological states, with the possible results that channels are not open, that one is open, or that two are open. Given a vector q in the channel state, we can compute the probability for the given configuration q of states in the channels. Associating a probability to any configuration, there are configurations with very low probability and configurations with high probability. Given the join probability P, we compute the variation of the probability with respect to the state qj. Given the current ij, we can compute the flux of states for the current as a random variable. Assuming the invariant form , the flux is controlled by the probability in an inverse way, and it is zero when the probability is a constant value. Therefore, we have three different powers: W1, the ordinary power for the ionic current without noise, W1,2, the flux of power from current to the noise current, and W2 as power in the noise currents.

- (c)

- About the Fisher information in neurodynamics, computing the average of power as the cost function with a minimum value, we can consider a parametrized family of probability distributions S = {P(x, t ,q1, q2 ,..., qn)}, with random variables x and t, and qi real vector parameters specifying the distribution. The family is regarded as an n-dimensional manifold having q as a coordinate system; it is a Riemannian manifold, and G(q) plays the role of a Fisher information matrix. The underlying idea of information geometry is to think the family of probability distributions as a space, each distribution being a “point,” while the parameters q plays the role of coordinates. There is a natural unique way for measuring the extent to which neighboring “points” can be distinguished from each other; it has all wished properties for imposing upon a measure of distance, thus keeping “distinguishable” the distance. Considering the well known Kullback-Leibler divergence, with noise equal to zero, the Fisher information assumes the maximum value and the geodesic becomes the classical geodesic. In the case of noise, the information approaches zero, and the cost function is reduced. Resistor networks provide the natural generalization of the lattice models for which percolation thresholds and percolation probabilities can be considered. The geodesic results composed by two parts: the “synchronic and crisp geodesic” and the “noise change of the crisp and synchronic geodesic” (Figure 1).

- (d)

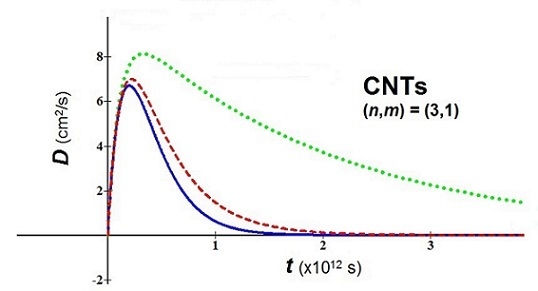

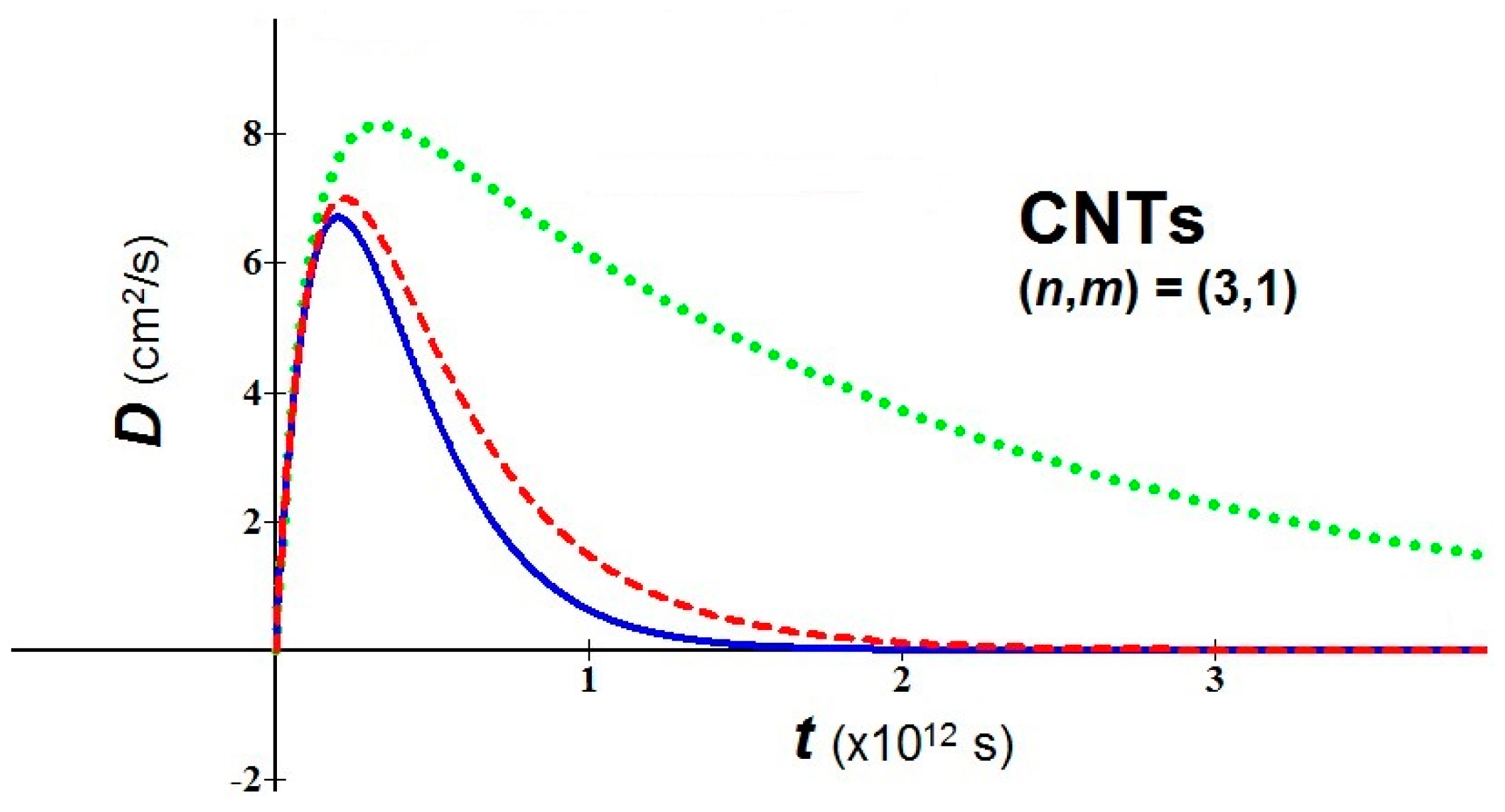

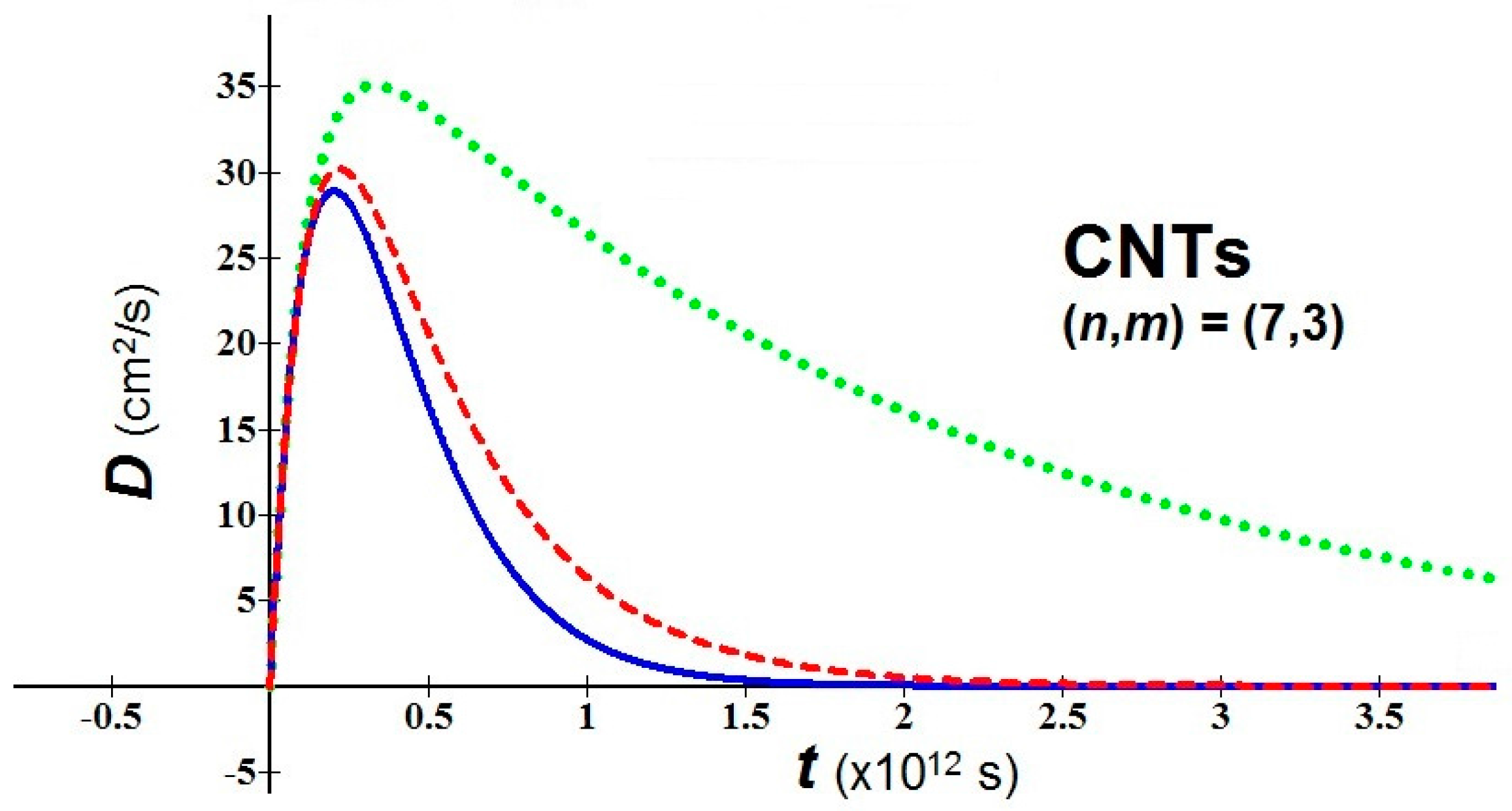

- In bio-molecules, it is easy to understand that the natural computation is more suitable than the Turing computation. The proposed nanobio approach takes back the attention toward geometric patterns and attractors. As examples of application, we consider a nanomaterial of great interest in nanomedicine, the fullerene in tubular form, i.e. carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and we study the behavior of their diffusion using the new proposed analytical model. For the used values, the temperature T = 310 K, three values of the parameter (0.1, 0.5, 0.9), an average relaxation time (the relaxation time in soft condensed matter takes values of order of 10−12–10−14 s), and two values of m* in relation to the variation of the chiral vector (n,m) have been fixed [27]:(a) (n,m) = (3,1) → meff = 0.507me(b) (n,m) = (7,3) → meff = 0.116me(me = mass of the electron = 9.109 × 10−31 kg)

- (a)

- The usefulness of a analogic and continuous computation, to which Turing returned with his work on morphogenesis. This kind of computation takes into account the fact that, in these systems, the boundary conditions and the environment are often important; therefore, not everything can be algorithmized;

- (b)

- The usefulness of nano-modeling at this level, which is able to locally provide interesting help in the study of brain dynamics and brain processes.

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- The memory in the neural network, as a non-passive element for storing information: Memory is integrated in the neural parameters as synaptic conductances, which give the geodesic trajectories in the non-orthogonal space of the free states. The optimal non-linear dynamics is a geodesic inside the deformed space that directs the neural computation. This approach provides the ability to mathematically set up the Freeman hypothesis on the intentionality as “optimal emergency” in the “system/environment” relations [28].

- (b)

- A new transport model, based on analytical expressions of the three most important parameters related to transport processes: It holds both for the motion of carriers inside a nanostructure, as considered in this paper, and for the motion of nanoparticles inside the human body, because of an inner gauge factor, allowing its use from sub-pico-level to macro-level. The model can be used to understand and manage existing data, but also to give predictions concerning, for example, the best nanomaterial in a particular situation with peculiar characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacLennan, B.J. Molecular coordination of hierarchical self-assembly. Nano Commun. Netw. 2012, 3, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.M.; Weiss, P.S. Nano in the Brain: Nano-Neuroscience. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8463–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claridge, S.A.; Schwartz, J.J.; Weiss, P.S. Electrons, Photons, and Force: Quantitative Single-Molecule Measurements from Physics to Biology. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 693–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Sia, P. Analytical Nano-Modeling for Neuroscience and Cognitive Science. J. Bioinform. Intell. Control 2014, 3, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichle, M.E. A brief history of human brain mapping. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, L.O. Memristor, Hodgkin-Huxley, and Edge of Chaos. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 383001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetzlaff, R. Memristors and Memristive Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. Memristor-based neural networks. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, M.A.; Molter, T.W. A HaH Computing-Metastable Switches to Attractors to Machine Learning. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 0085175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resconi, G.; Licata, I. Computation by Intention and Electronic Image of the Brain. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2015, 4, 232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Licata, I. Effective Physical Processes and Active Information in Quantum Computing. Quantum Biosyst. 2007, 1, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Licata, I. Beyond Turing: Hypercomputation and Quantum Morphogenesis. Asia Pac. Math. Newslett. 2012, 2, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan, B. Natural computation and non-Turing models of computation. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2004, 317, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivisatos, A.P.; Andrews, A.M.; Boyden, E.S.; Chun, M.; Church, G.M.; Deisseroth, K.; Donoghue, J.P.; Fraser, S.E.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Looger, L.L.; et al. Nanotools for neuroscience and brain activity mapping. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1850–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.L. Toward self-powered sensor networks. Nano Today 2010, 5, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Foster, R. Wireless body sensor networks for health monitoring applications. Physiol. Meas. 2008, 29, R27–R56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Jang, E.Y.; Lee, N.J.; Choi, D.J.; Lee, K.J.; Jang, J.T.; Choi, J.S.; Moon, S.H.; Cheon, J. Nanoparticle Assemblies as Memristors. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 2229–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.K. Nanomedicine for Drug Delivery and Therapeutics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, F.A.C.; Carvalho, L.R.B.; Grinberg, L.T.; Farfel, J.M.; Ferretti, R.E.L.; Leite, R.E.P.; Filho, W.J.; Lent, R.; Herculano-Houzel, S. Equal Numbers of Neuronal and Nonneuronal Cells Make the Human Brain an Isometrically Scaled-Up Primate Brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009, 513, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alivisatos, A.P.; Chun, M.; Church, G.M.; Greenspan, R.J.; Roukes, M.L.; Chun Yuste, R. The Brain Activity Map Project and the Challenge of Functional Connectomics. Neuron 2012, 74, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.A.L. Soft Condensed Matter: Oxford Master Series in Condensed Matter Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sia, P. An Analytical Transport Model for Nanomaterials. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2011, 8, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sia, P. An Analytical Transport Model for Nanomaterials: The Quantum Version. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2012, 9, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sia, P. Nanotechnology between Classical and Quantum Scale: Applications of a new interesting analytical Model. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2012, 17, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sia, P. Interesting Details about Diffusion of Nanoparticles for Diagnosis and Treatment in Medicine by a new analytical theoretical Model. J. Nanotechnol. Diagn. Treat. 2014, 2, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sia, P. Relativistic nano-transport and artificial neural networks: Details by a new analytical model. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Mechatron. 2014, 3, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Marulanda, J.M.; Srivastava, A. Carrier Density and Effective Mass Calculation for carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2008, 245, 2558–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, W. Nonlinear Dynamics of Intentionality. J. Mind Behav. 1997, 18, 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Resconi, G.; Licata, I. Beyond an Input/Output Paradigm for Systems: Design Systems by Intrinsic Geometry. Systems 2014, 2, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenberg, G.; Back, T.; Kok, J. Handbook of Natural Computing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Sia, P.; Licata, I. Nano-Modeling and Computation in Bio and Brain Dynamics. Bioengineering 2016, 3, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering3020011

Di Sia P, Licata I. Nano-Modeling and Computation in Bio and Brain Dynamics. Bioengineering. 2016; 3(2):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering3020011

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Sia, Paolo, and Ignazio Licata. 2016. "Nano-Modeling and Computation in Bio and Brain Dynamics" Bioengineering 3, no. 2: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering3020011

APA StyleDi Sia, P., & Licata, I. (2016). Nano-Modeling and Computation in Bio and Brain Dynamics. Bioengineering, 3(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering3020011