Recent Advances in AI-Driven Mobile Health Enhancing Healthcare—Narrative Insights into Latest Progress

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Story of Mhealth

1.2. Current State of AI in mHealth

- Current trends: What are the main trends in AI use across different mHealth domains, and how rapidly is the technology being integrated into everyday healthcare practices?

- Categorization and impact: How can AI applications in mHealth be categorized, and which types show the greatest promise for improving patient outcomes and enhancing healthcare efficiency?

- Opportunities and challenges: What are the main opportunities offered by AI, and what challenges—including regulatory, ethical, and implementation-related barriers—need to be addressed to ensure safe, equitable, and effective deployment?

1.3. Purpose of the Narrative Review

- Trends: Examine the evolution and current trends in AI use in mHealth, including key areas of application such as chronic disease management, telemedicine, and mental health.

- Categorization: Classify AI-based mobile health tools and interventions, identifying those that are most effective and those that are emerging.

- Opportunities and Challenges: Evaluate the opportunities AI offers for improving healthcare delivery and accessibility, and address key challenges, including data privacy, regulatory frameworks, and healthcare system integration.

2. Methods

2.1. Narrative Review Approach, Search Strategy, and Quality Assessment

2.1.1. Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Scope

2.1.2. Selection and Qualification of Reviews

- 1.

- Define inclusion criteria

- ∘

- Primarily systematic reviews and meta-analyses were considered to ensure a high level of methodological rigor and robustness of evidence.

- ∘

- In addition, a limited number of non-systematic (narrative or scoping) reviews were included to capture emerging applications, innovative trends, and areas where systematic evidence is still limited.

- ∘

- Studies had to focus on clinical or healthcare applications of AI in mHealth, excluding purely technical or algorithmic works without tangible clinical outcomes.

- ∘

- Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria are reported in Table 2.

- 2.

- Initial screening

- ∘

- Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers.

- ∘

- Studies irrelevant to clinical mHealth applications, such as purely computational benchmarks or software architecture reports, were excluded.

- 3.

- Evaluation parametersEach study was assessed using six core parameters:

- ∘

- N1: Clear rationale—The study clearly explains the background, objectives, and significance.

- ∘

- N2: Adequate research design—Methodology is appropriate to answer the research question.

- ∘

- N3: Clearly described methodology—Data collection, analysis, and interpretation are transparent and replicable.

- ∘

- N4: Well-presented results—Results are clearly described, with tables, figures, or statistical analysis supporting conclusions.

- ∘

- N5: Conclusions justified by results—Conclusions are evidence-based and logically derived.

- ∘

- N6: Disclosure of conflicts of interest—Conflicts of interest are explicitly reported.

- 4.

- Scoring system

- ∘

- N1–N5 were scored on a 1–5 scale (1 = poor, 5 = excellent).

- ∘

- N6 was assessed as Yes/No (Yes = disclosed; No = not disclosed).

- 5.

- Preselection of studies

- ∘

- Only studies with N1–N5 > 3 and N6 = Yes were preselected.

- ∘

- This ensured inclusion of methodologically robust studies with transparency in conflicts of interest.

- 6.

- Final synthesis

- ∘

- Preselected studies were included in the narrative synthesis, providing a clinically focused overview of trends, categories, and challenges in AI-driven mHealth.

- ∘

- The synthesis emphasized post-pandemic developments, highlighting how technological innovation intersects with practical healthcare applications.

2.2. Screening Team and Reliability Assessment

- For N1–N5, a 5-point scale was applied: 1 = Poor, 2 = Fair, 3 = Good, 4 = Very Good, 5 = Excellent.

- N6 was assessed binary (Yes/No), depending on whether conflicts of interest were explicitly disclosed.

3. Results

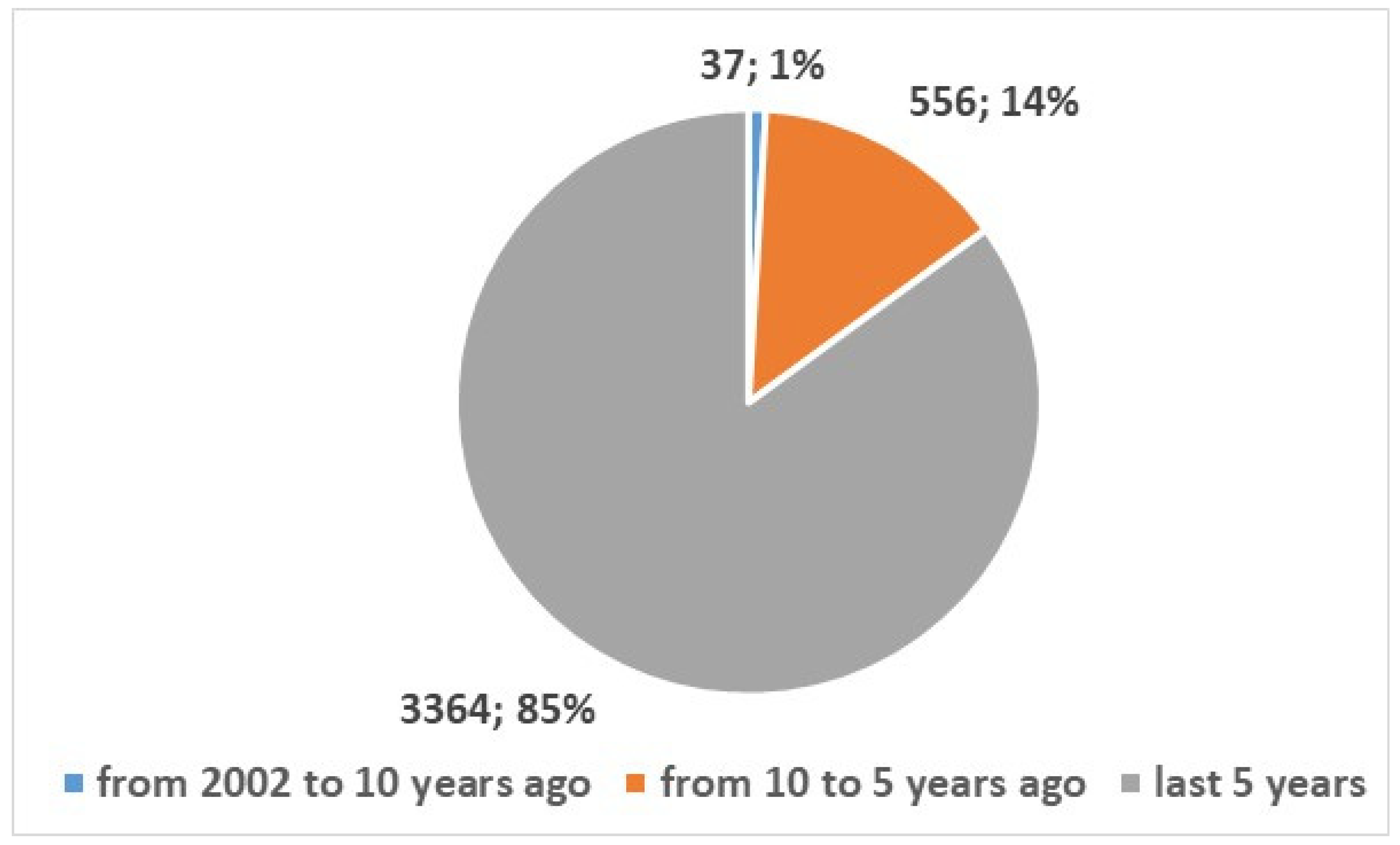

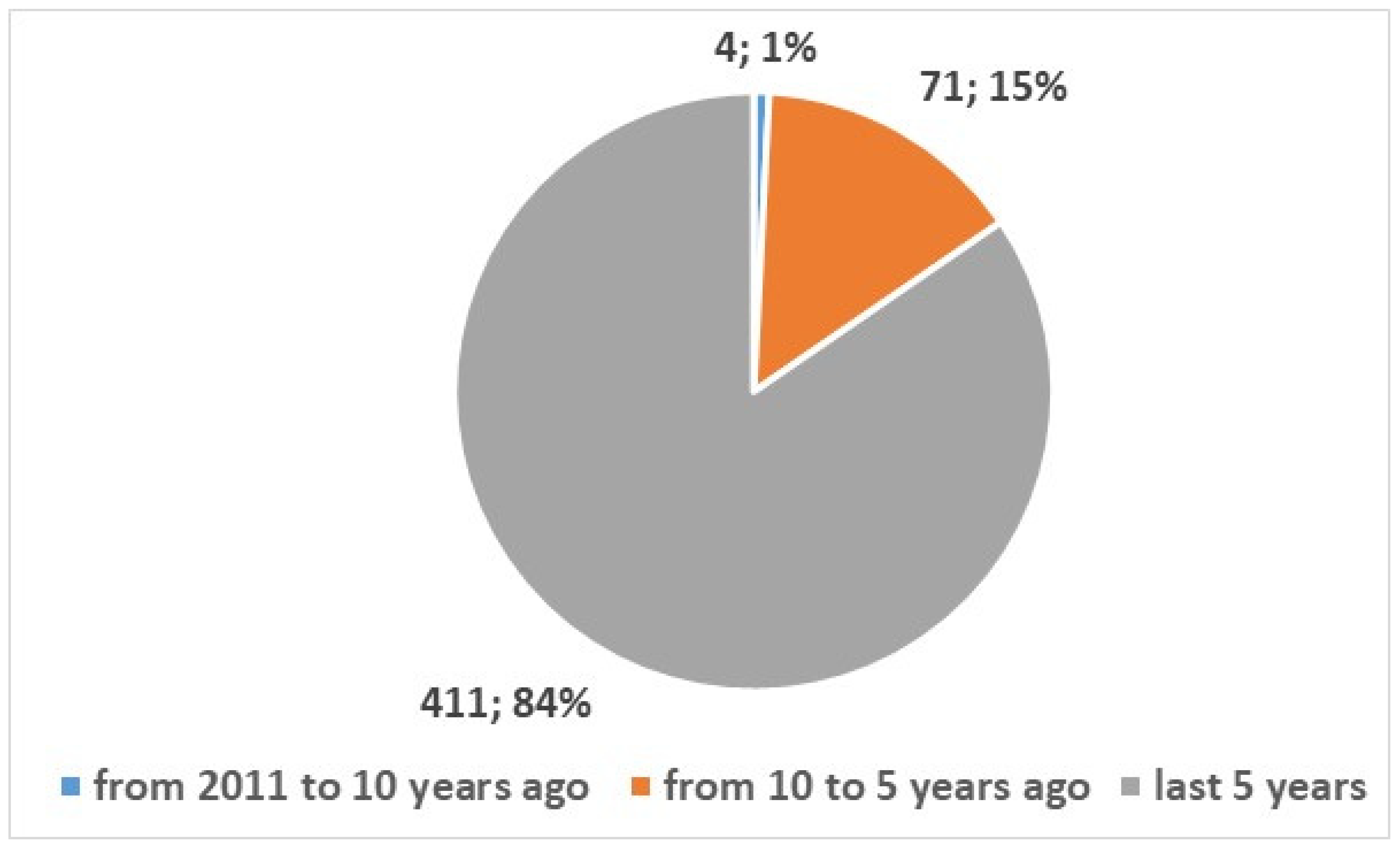

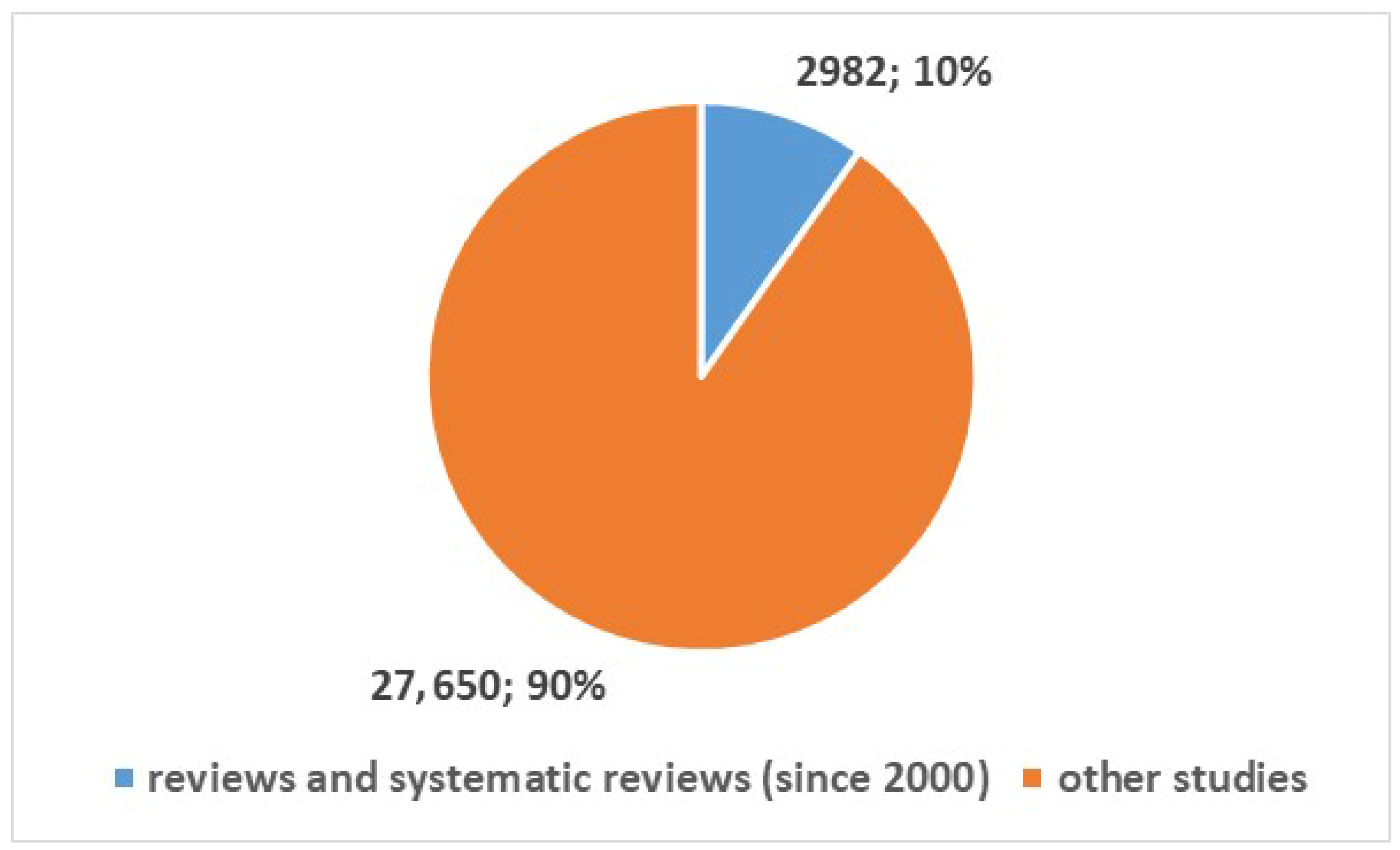

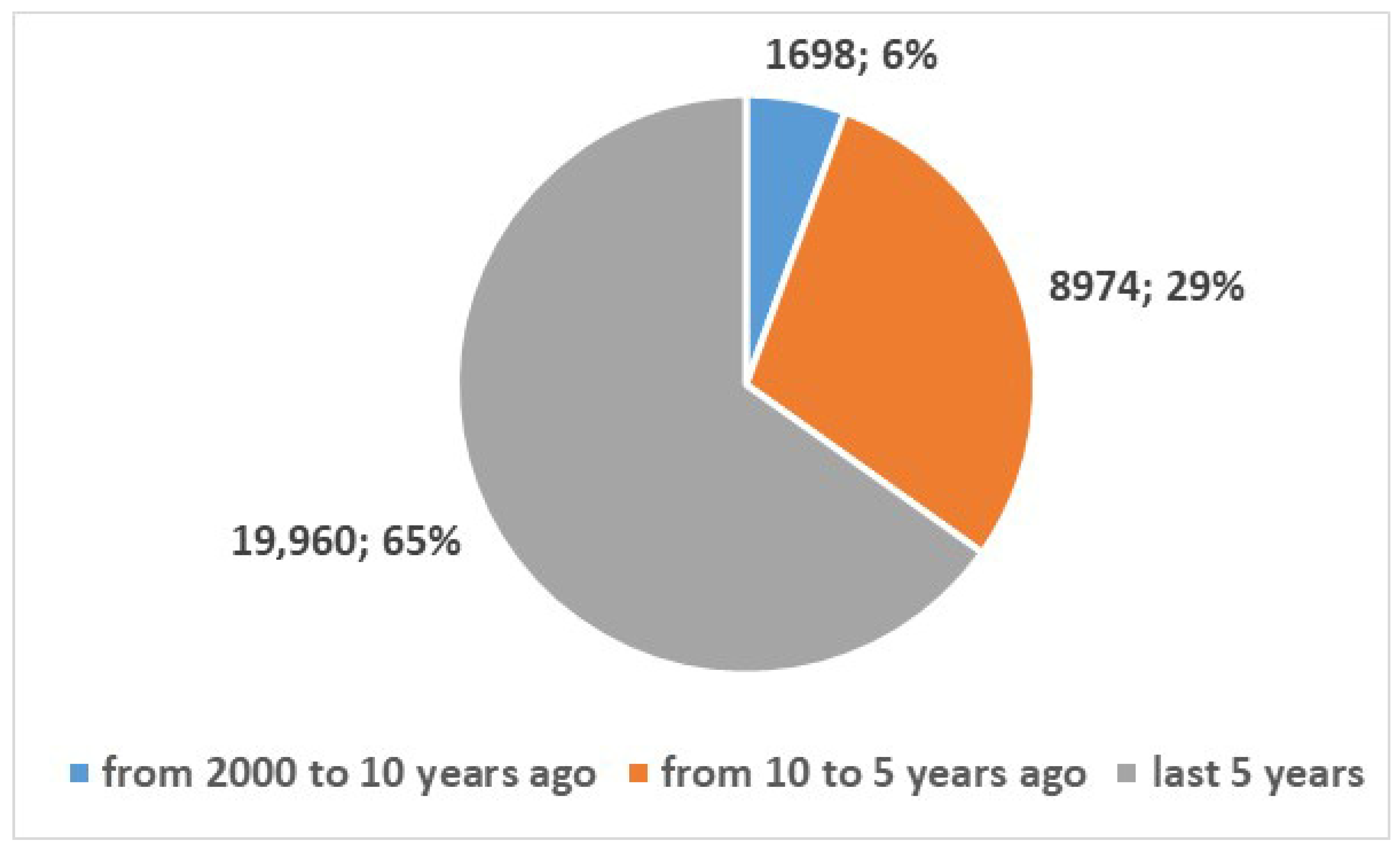

3.1. Study Selection Flow

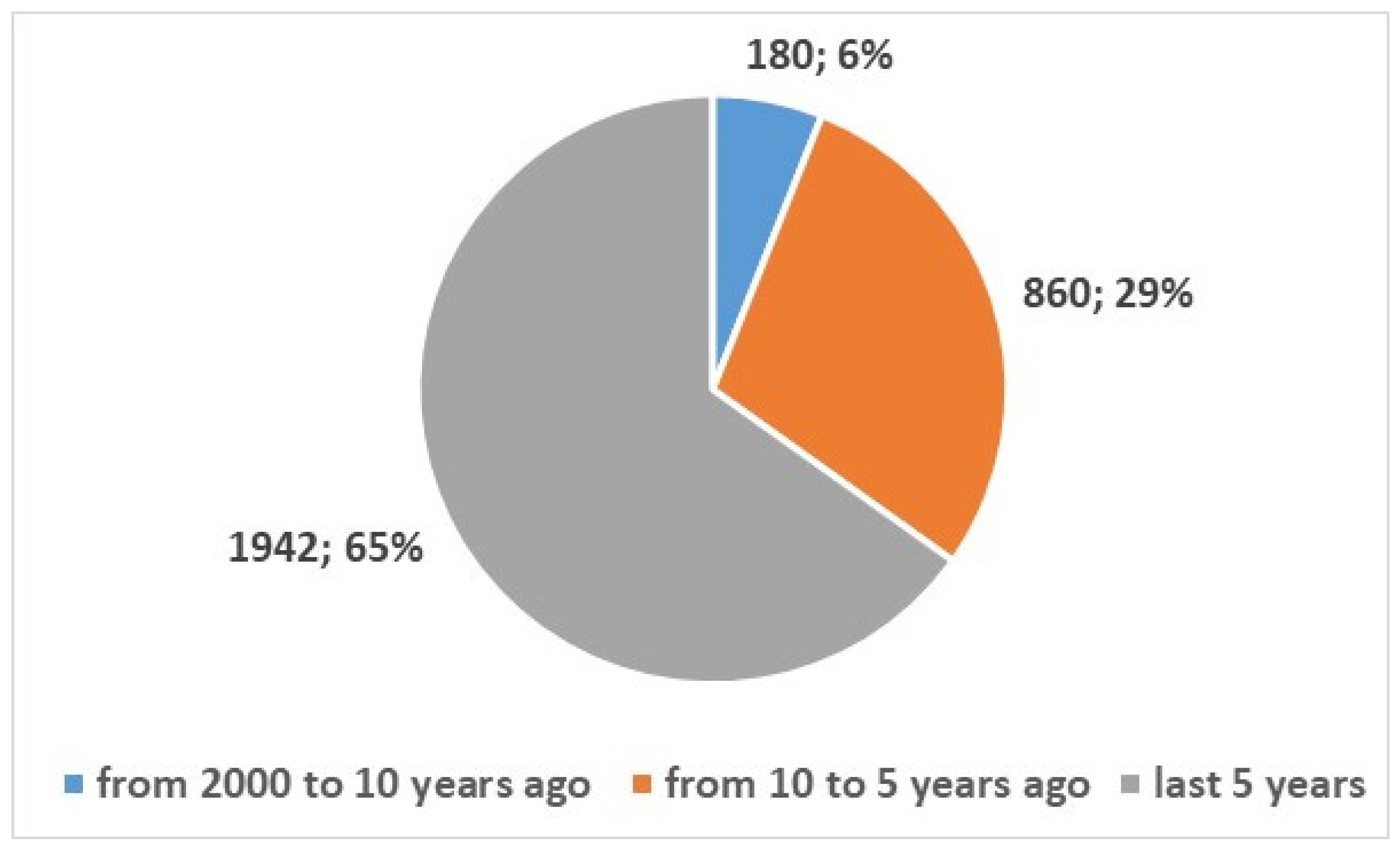

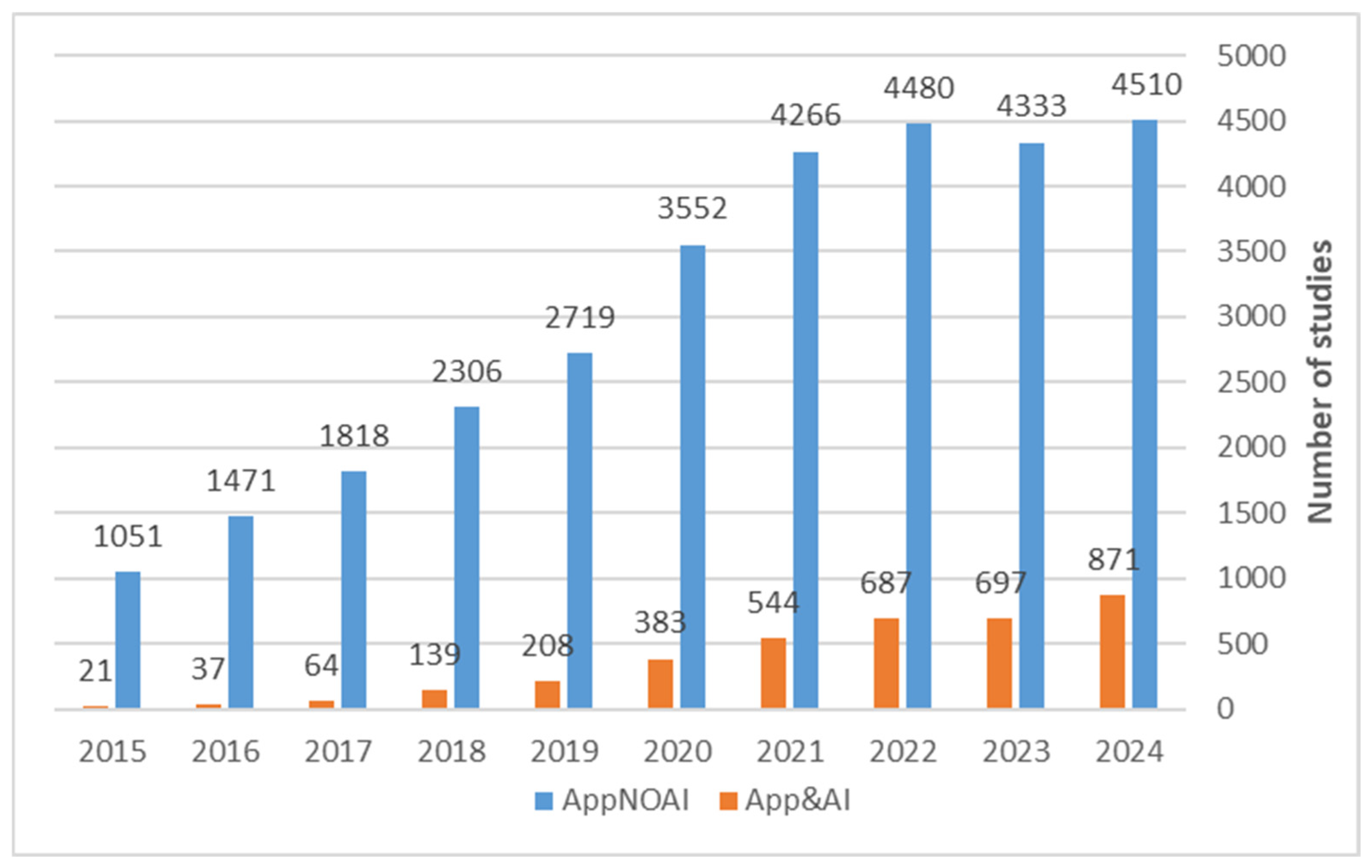

3.2. Research Trends in Mobile Apps and Their Use of Artificial Intelligence

3.3. Output from the Overview: Common Message, Themes and Categorization

- Macro Area: The broad healthcare category where AI and mHealth applications have been applied.

- Number of Included Studies: Total studies contributing to each macro-area, allowing a quick assessment of research volume.

- Evidence Maturity Level: Qualitative assessment of research maturity (e.g., emerging, developing, mature) based on the number and quality of studies.

- Typical Interventions/Focus: Provides a brief summary (1–2 sentences) of the typical interventions, aims, or contributions of the studies in that macro-area.

- Notes/Research Gaps: Highlights areas with limited evidence or underexplored topics, guiding directions for future investigation.

- Key Studies [ ]: Lists the included studies for each macro-area using numerical references corresponding to the reference list.

- Workplace Health: AI-based interventions to promote employee health and prevent disease [28].

- Technology for Medication Adherence: mHealth apps improving adherence to treatments, particularly in oncology [29].

- Nutrition & Health: Mobile apps supporting nutrition management and healthier behaviors [34].

- Surgical Care & Infections: Data-driven technologies preventing surgical site infections [54].

- Medical Informatics: Telehealth startups enhancing healthcare delivery and access [53].

3.4. Opportunities and Areas Needing Broader Investigation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. Comparison with Prior Evidence

4.3. Exploring Clinical and Policy Implications

4.4. Exploring the Regulatory Landscape Surrounding AI-Powered Mobile Health Apps

4.4.1. Characteristics of the AI-Based App Concerning Medical Device Regulation

- -

- Transparency of algorithms (known as ‘black boxes’), which do not allow clinicians to understand or verify the decisions made by the algorithm;

- -

- Effectiveness, since unlike traditional software, artificial intelligence systems can change their behaviour over time, which can lead to unnecessary treatments or missed diagnoses;

- -

- Depending on the input data, there is a risk of bias if the training data has not been diversified;

- -

- Data security and privacy, as there is a risk of accidental data loss and cyberattacks;

- -

- Regulatory and legal uncertainty, as the regulatory frameworks of various countries are still evolving.

4.4.2. Characteristics of the AI-Based App Concerning AI Regulation

- Robustness and safety: AI systems must operate reliably and safely.

- Privacy and security: AI systems must respect privacy (mandatory information on how data are collected, used, and stored.) and must be secure (system access and data encryption to ensure data quality and integrity).

- Transparency and explainability: AI operations must be understandable to users and stakeholders, from training on the data and algorithms to generating the final model.

- Fairness and inclusiveness: AI outcomes must avoid bias and discrimination toward or against certain groups of people.

- Accountability: There must be clear responsibilities for the results of the AI system, such as to the developers who design and deploy the AI system.

4.5. Quality Aspects in AI & Apps

4.5.1. Policy and Global Strategies

4.5.2. Clinical Evidence and Effectiveness

- Mental health interventions: Apps delivering mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or stress reduction programs improve well-being, reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms, and enhance coping skills [110,111]. Integration of AI-driven personalization allows dynamic adaptation of content, reminders, and exercises based on individual user progress, engagement patterns, and risk profiles.

- Chronic disease management: Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular apps facilitate lifestyle modification, medication adherence, and biometric monitoring, demonstrating improvements in glycemic control, blood pressure, and symptom management [112,113,114]. AI models can identify early deviations from expected health parameters, alert patients and clinicians, and recommend timely interventions.

- Oncology care: Mobile apps support cancer survivors in self-management, symptom tracking, and psychological support, improving quality of life and reducing stress [115,116]. Predictive analytics enable anticipation of side effects or disease progression, allowing personalized follow-up schedules and care adjustments.

- Respiratory disease support: Asthma and COPD apps enhance adherence, track inhaler usage, and provide environmental alerts [117]. AI personalization can optimize medication timing, offer actionable recommendations, and support behavior change interventions to reduce exacerbations.

4.5.3. Economic Evidence and System-Level Impact

4.5.4. Adoption and Usability

- Clinician adoption: Healthcare providers consider usability, evidence of clinical effectiveness, integration with electronic health records, and compatibility with existing workflows [121]. AI recommendations must be transparent, interpretable, and explainable to gain trust and support clinical decision-making.

- Patient uptake: Sociotechnical factors—such as digital literacy, engagement strategies, trust in data handling, and behavioral design—affect sustained use [122]. Personalized notifications, gamification, and interactive feedback can improve adherence.

4.5.5. App Assessment Frameworks and Standardization

- European mHealth Hub: Offers comprehensive guidelines to assess app features, clinical validation, usability, and cybersecurity [127].

- CEN ISO/TS 82304-2: Internationally recognized criteria cover safety, effectiveness, interoperability, engagement, and transparency, supporting consistent and reproducible evaluation [128].

4.6. Technical Standards and Norms for AI-Powered Health Apps

4.6.1. ISO and IEC Standards

4.6.2. Health IT and Interoperability Standards

4.6.3. AI-Specific Guidelines and Regulatory Alignment

4.6.4. Quality Assessment, Certification, and Continuous Monitoring

4.7. The Regulatory Gray Zone and AI-Specific Advantages in mHealth

4.7.1. The Regulatory Gray Zone in mHealth Applications

4.7.2. AI-Specific Advantages vs. Traditional mHealth Tools

- Real-time Pattern Recognition and Anomaly DetectionAI algorithms can analyze continuous streams of patient data to detect subtle anomalies that human observers or traditional apps may miss. For example, in diabetes management, AI-enabled apps can monitor glucose trends and detect patterns predicting hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, allowing for early interventions [112,114]. Similarly, AI can identify early signs of cardiac arrhythmias from wearable ECG data, outperforming rule-based alerts provided by standard apps.

- Personalization Based on Individual DataUnlike conventional mHealth tools, AI can tailor interventions to each user’s unique physiology, behavior, and health history. In oncology, AI-driven apps can provide individualized medication reminders and lifestyle recommendations for breast cancer survivors [115,116]. In mental health, AI chatbots can adapt counseling content based on real-time mood assessments, optimizing engagement and efficacy [96,98].

- Predictive Modeling and Risk StratificationAI supports predictive analytics, allowing clinicians and patients to anticipate future health events. For example, AI tools can stratify cardiovascular risk by integrating patient demographics, lab results, and lifestyle data, guiding preventive interventions [115,117]. Predictive modeling can also prioritize high-risk patients for early monitoring, reducing hospitalizations and healthcare costs.

- Natural Language Processing for Symptom AssessmentAI-powered natural language processing (NLP) enables apps to interpret unstructured patient-reported information. Chatbots and digital symptom checkers can understand patient inputs in free text, detect critical symptoms, and triage patients appropriately [96,98]. This functionality is particularly valuable in mental health, where subjective symptom reporting is crucial.

4.7.3. Implications for Practice and Policy

4.8. Limitations

4.9. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giansanti, D.; Maccioni, G.; Grigioni, M. Biotelemetry for monitoring the quality of life of pets: What has changed since Laika? Not. Ist. Super. Sanità 2017, 30, 3–8. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://biotelemetry.yolasite.com/history.php (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Available online: https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/inventing-apollo-spaceflight-biomedical-sensors (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Bonato, P. Wearable sensors/systems and their impact on biomedical engineering. IEEE Eng. Med. Boil. Mag. 2003, 22, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.arrow.com/en/research-and-events/articles/smartphone-history-from-the-first-smartphone-to-today (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Fiordelli, M.; Diviani, N.; Schulz, P.J. Mapping mHealth research: A decade of evolution. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hobson, G.R.; Caffery, L.J.; Neuhaus, M.; Langbecker, D.H. Mobile Health for First Nations Populations: Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e14877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holl, F.; Schobel, J.; Swoboda, W.J. Mobile Apps for COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Healthcare 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, F.; Darvishpour, A. Mobile Health Applications in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of the Reviews. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2023, 37, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maccioni, G.; Giansanti, D. Medical Apps and the Gray Zone in the COVID-19 Era: Between Evidence and New Needs for Cybersecurity Expansion. Healthcare 2021, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabla, P.K.; Gruson, D.; Gouget, B.; Bernardini, S.; Homsak, E. Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic: Emphasizing the Emerging Role and Perspectives from Artificial Intelligence, Mobile Health, and Digital Laboratory Medicine. eJIFCC 2021, 32, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alkasassbeh, J.S.; Alawneh, T.A.; Al-Qaisi, A.; Altarawneh, M.; alja’fari, M. The Role of AI in Mobile Apps to Combat Future Pandemics: A COVID-19 Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Engineering Conference on Electrical, Energy, and Artificial Intelligence (EICEEAI), Zarqa, Jordan, 27–28 December 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahroz, M.; Ahmad, F.; Younis, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Kamel Boulos, M.N.; Vinuesa, R.; Qadir, J. COVID-19 digital contact tracing applications and techniques: A review post initial deployments. Transp. Eng. 2021, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.A.; Hartanti, I.R.; Colin, M.N.; Pitaloka, D.A. Telemedicine and artificial intelligence to support self-isolation of COVID-19 patients: Recent updates and challenges. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Solimini, R.; Busardò, F.P.; Gibelli, F.; Sirignano, A.; Ricci, G. Ethical and Legal Challenges of Telemedicine in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina 2021, 57, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritikos, M. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in a Time of Pandemics: Developing Options for the Ethical Governance of COVID-19 AI Applications. In Ethics, Integrity and Policymaking: The Value of the Case Study; Chapter 13; O’Mathúna, D., Iphofen, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastrucci, A.; Pirrera, A.; Lepri, G.; Giansanti, D. Algorethics in Healthcare: Balancing Innovation and Integrity in AI Development. Algorithms 2024, 17, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singareddy, S.; Sn, V.P.; Jaramillo, A.P.; Yasir, M.; Iyer, N.; Hussein, S.; Nath, T.S. Artificial Intelligence and Its Role in the Management of Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Sun, D.; Yi, M.; Wang, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Telemedicine: A Global Perspective Visualization Analysis. Telemed. e Health 2024, 30, e1909–e1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giansanti, D.; Morelli, S. Exploring the Potential of Digital Twins in Cancer Treatment: A Narrative Review of Reviews. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Hung, C.; Katapally, T.R. Evaluating predictive artificial intelligence approaches used in mobile health platforms to forecast mental health symptoms among youth: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 343, 116277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyazewal, T.; Davey, G.; Hanlon, C.; Newport, M.J.; Hopkins, M.; Wilburn, J.; Bakhiet, S.; Mutesa, L.; Semahegn, A.; Assefa, E.; et al. Innovative technologies to address neglected tropical diseases in African settings with persistent sociopolitical instability. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thakuria, T.; Rahman, T.; Mahanta, D.R.; Khataniar, S.K.; Goswami, R.D.; Rahman, T.; Mahanta, L.B. Deep learning for early diagnosis of oral cancer via smartphone and DSLR image analysis: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Med. Dev. 2024, 21, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förstel, M.; Haas, O.; Förstel, S.; Maier, A.; Rothgang, E. A Systematic Review of Features Forecasting Patient Arrival Numbers. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2024, 43, e01197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, R.C.; Thu, K.M.; Hsung, R.T.; McGrath, C.; Lam, W.Y. Self-monitoring of Oral Health Using Smartphone Selfie Powered by Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Preventive Dentistry. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2024, 22, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, B.; Babineau, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Mihailidis, A. Smartphone-Based Hand Function Assessment: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e51564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Negi, S.; Mathur, A.; Tripathy, S.; Mehta, V.; Snigdha, N.T.; Adil, A.H.; Karobari, M.I. Artificial Intelligence in Dental Caries Diagnosis and Detection: An Umbrella Review. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lange, M.; Löwe, A.; Kayser, I.; Schaller, A. Approaches for the Use of AI in Workplace Health Promotion and Prevention: Systematic Scoping Review. JMIR AI 2024, 3, e53506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chow, S.M.; Tan, B.K. Effectiveness of mHealth apps on adherence and symptoms to oral anticancer medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, K.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Tham, Y.C.; Koh, V.; Zhao, Y.; Kawasaki, R.; Grzybowski, A.; Ye, J. Integration of smartphone technology and artificial intelligence for advanced ophthalmic care: A systematic review. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2024, 4, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choi, A.; Ooi, A.; Lottridge, D. Digital Phenotyping for Stress, Anxiety, and Mild Depression: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e40689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Segur-Ferrer, J.; Moltó-Puigmartí, C.; Pastells-Peiró, R.; Vivanco-Hidalgo, R.M. Methodological Frameworks and Dimensions to Be Considered in Digital Health Technology Assessment: Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e48694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giunti, G.; Doherty, C.P. Cocreating an Automated mHealth Apps Systematic Review Process with Generative AI: Design Science Research Approach. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e48949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pala, D.; Petrini, G.; Bosoni, P.; Larizza, C.; Quaglini, S.; Lanzola, G. Smartphone applications for nutrition Support: A systematic review of the target outcomes and main functionalities. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 184, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, E.; Almansour, R.; Ijaz, K.; Baptista, S.; Giordan, L.B.; Ronto, R.; Zaman, S.; O’Hagan, E.; Laranjo, L. Smartphone Applications to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 66, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheisari, M.; Ghaderzadeh, M.; Li, H.; Taami, T.; Fernández-Campusano, C.; Sadeghsalehi, H.; Afzaal Abbasi, A. Mobile Apps for COVID-19 Detection and Diagnosis for Future Pandemic Control: Multidimensional Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e44406, Erratum in JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e58810. https://doi.org/10.2196/58810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tomlin, H.R.; Wissing, M.; Tanikella, S.; Kaur, P.; Tabas, L. Challenges and Opportunities for Professional Medical Publications Writers to Contribute to Plain Language Summaries (PLS) in an AI/ML Environment—A Consumer Health Informatics Systematic Review. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2024, 2023, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xue, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, N.; Li, Z.; Fu, W.; et al. Evaluation of the Current State of Chatbots for Digital Health: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, X.; Zheng, X.; Ding, H. Existing Barriers Faced by and Future Design Recommendations for Direct-to-Consumer Health Care Artificial Intelligence Apps: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e50342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sumner, J.; Lim, H.W.; Chong, L.S.; Bundele, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Kayambu, G. Artificial intelligence in physical rehabilitation: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 146, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendotti, H.; Lawler, S.; Chan, G.C.K.; Gartner, C.; Ireland, D.; Marshall, H.M. Conversational artificial intelligence interventions to support smoking cessation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231211634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pyper, E.; McKeown, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Powell, J. Digital Health Technology for Real-World Clinical Outcome Measurement Using Patient-Generated Data: Systematic Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e46992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasan, S.U.; Siddiqui, M.A.R. Diagnostic accuracy of smartphone-based artificial intelligence systems for detecting diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 205, 110943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Prinz, A.; Riegler, M.A.; Das, J. A systematic review and knowledge mapping on ICT-based remote and automatic COVID-19 patient monitoring and care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fegan, H.; Hutchinson, R. Is the answer to reducing early childhood caries in your pocket? Evid. Based Dent. 2023, 24, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumpouros, Y.; Georgoulas, A. Pain Management Mobile Applications: A Systematic Review of Commercial and Research Efforts. Sensors 2023, 23, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duarte, M.; Pereira-Rodrigues, P.; Ferreira-Santos, D. The Role of Novel Digital Clinical Tools in the Screening or Diagnosis of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, X.; Martinengo, L.; Jabir, A.I.; Ho, A.H.Y.; Car, J.; Atun, R.; Tudor Car, L. Scope, Characteristics, Behavior Change Techniques, and Quality of Conversational Agents for Mental Health and Well-Being: Systematic Assessment of Apps. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moharrami, M.; Farmer, J.; Singhal, S.; Watson, E.; Glogauer, M.; Johnson, A.E.W.; Schwendicke, F.; Quinonez, C. Detecting dental caries on oral photographs using artificial intelligence: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 1765–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piendel, L.; Vališ, M.; Hort, J. An update on mobile applications collecting data among subjects with or at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1134096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lam, W.W.T.; Tang, Y.M.; Fong, K.N.K. A systematic review of the applications of markerless motion capture (MMC) technology for clinical measurement in rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sumra, M.; Asghar, S.; Khan, K.S.; Fernández-Luna, J.M.; Huete, J.F.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Smartphone Apps for Domestic Violence Prevention: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chakraborty, I.; Edirippulige, S.; Vigneswara Ilavarasan, P. The role of telehealth startups in healthcare service delivery: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 174, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irgang, L.; Barth, H.; Holmén, M. Data-Driven Technologies as Enablers for Value Creation in the Prevention of Surgical Site Infections: A Systematic Review. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2023, 7, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torres-Guzman, R.A.; Paulson, M.R.; Avila, F.R.; Maita, K.; Garcia, J.P.; Forte, A.J.; Maniaci, M.J. Smartphones and Threshold-Based Monitoring Methods Effectively Detect Falls Remotely: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Eijck, S.C.; Janssen, D.M.; van der Steen, M.C.; Delvaux, E.J.L.G.; Hendriks, J.G.E.; Janssen, R.P.A. Digital Health Applications to Establish a Remote Diagnosis of Orthopedic Knee Disorders: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rahman, M.H.; Usmani, N.G.; Chandra, P.; Manna, R.M.; Ahmed, A.; Shomik, M.S.; Arifeen, S.E.; Hossain, A.T.; Rahman, A.E. Mobile Apps to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG): Systematic App Research and Content Analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e66247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdul Latif El Ejel, B.; Sattar, S.; Fatima, S.B.; Khan, H.N.; Ali, H.; Iftikhar, A.; Sarwer, M.A.; Mushtaq, M. Digital Diabetes Management Technologies for Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Home-Based Care Interventions. Cureus 2025, 17, e84177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jafari, B.; Amiri, M.R.; Labecka, M.K.; Rajabi, R. The effect of home-based and remote exercises on low back pain during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systemic review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2025, 43, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijendran, S.; Alok, Y.; Kuzhuppilly, N.I.R.; Bhat, J.R.; Kamath, Y.S. Effectiveness of smartphone technology for detection of paediatric ocular diseases-a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andrade, L.I.; Viñán-Ludeña, M.S. Mapping research on ICT addiction: A comprehensive review of Internet, smartphone, social media, and gaming addictions. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1578457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sylla, B.; Ismaila, O.; Diallo, G. 25 Years of Digital Health Toward Universal Health Coverage in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Rapid Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e59042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaap, G.; Butt, B.; Bode, C. Suitability of just-in-time adaptive intervention in post-COVID-19-related symptoms: A systematic scoping review. PLoS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhuang, M.; Hassan, I.I.; WAhmad, W.M.A.; Abdul Kadir, A.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.; Guan, Y.; Song, S. Effectiveness of Digital Health Interventions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e76323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhong, R.; Wu, X.; Chen, J.; Fang, Y. Using Digital Phenotyping to Discriminate Unipolar Depression and Bipolar Disorder: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e72229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kargarandehkordi, A.; Li, S.; Lin, K.; Phillips, K.T.; Benzo, R.M.; Washington, P. Fusing Wearable Biosensors with Artificial Intelligence for Mental Health Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Biosensors 2025, 15, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Melia, R.; Musacchio Schafer, K.; Rogers, M.L.; Wilson-Lemoine, E.; Joiner, T.E. The Application of AI to Ecological Momentary Assessment Data in Suicide Research: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Woll, S.; Birkenmaier, D.; Biri, G.; Nissen, R.; Lutz, L.; Schroth, M.; Ebner-Priemer, U.W.; Giurgiu, M. Applying AI in the Context of the Association Between Device-Based Assessment of Physical Activity and Mental Health: Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2025, 13, e59660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dehbozorgi, R.; Zangeneh, S.; Khooshab, E.; Nia, D.H.; Hanif, H.R.; Samian, P.; Yousefi, M.; Hashemi, F.H.; Vakili, M.; Jamalimoghadam, N.; et al. The application of artificial intelligence in the field of mental health: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Genugten, C.R.; Thong, M.S.Y.; van Ballegooijen, W.; Kleiboer, A.M.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Smit, A.C.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Terhorst, Y.; Riper, H. Beyond the current state of just-in-time adaptive interventions in mental health: A qualitative systematic review. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1460167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdulazeem, H.; Borges do Nascimento, I.J.; Weerasekara, I.; Sharifan, A.; Grandi Bianco, V.; Cunningham, C.; Kularathne, I.; Deeken, G.; de Barros, J.; Sathian, B.; et al. Use of Digital Health Technologies for Dementia Care: Bibliometric Analysis and Report. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e64445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan, M.; Li, R.; Wei, J.; Peng, H.; Hu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Li, N.; Guo, Y.; Gu, W.; Liu, H. Application of artificial intelligence in the health management of chronic disease: Bibliometric analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1506641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Genovese, A.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Haider, S.A.; Prabha, S.; Forte, A.J.; Veenstra, B.R. Artificial intelligence in clinical settings: A systematic review of its role in language translation and interpretation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2024, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akbarian, P.; Asadi, F.; Sabahi, A. Developing Mobile Health Applications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review of Features and Technologies. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 2024, 16, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bernard, R.M.; Seijas, V.; Davis, M.; Volkova, A.; Diviani, N.; Lüscher, J.; Sabariego, C. Self-Management Support Apps for Spinal Cord Injury: Results of a Systematic Search in App Stores and Mobile App Rating Scale Evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e53677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, E.Y.; Tan, B.K.J.; Tan, N.K.W.; Ng, A.C.W.; Leong, Z.H.; Phua, C.Q.; Loh, S.R.H.; Uataya, M.; Goh, L.C.; Ong, T.H.; et al. Artificial intelligence facial recognition of obstructive sleep apnea: A Bayesian meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2024, 29, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMDRF SaMD Working Group. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Key Definitions. International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF), December 2013. Available online: https://www.imdrf.org/sites/default/files/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-131209-samd-key-definitions-140901.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/software-medical-device-samd (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Device Software Functions Including Mobile Medical Applications. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Health Canada. Guidance Document: Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Definition and Classification. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-devices/application-information/guidance-documents/software-medical-device-guidance-document.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), Australian Government. Understanding Regulation of Software-Based Medical Devices. Available online: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/guidance/understanding-regulation-software-based-medical-devices (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Medical Device Coordination Group Document. MDCG2019-11 Rev1. Guidance on Qualification Classification of Software in Regulation (EU) 2017/745–MDR and Regulation (EU) 2017/746–IVDR. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/b45335c5-1679-4c71-a91c-fc7a4d37f12b_en?filename=mdcg_2019_11_en.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software as a Medical Device. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-software-medical-device (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- ISO/DTS 24971-2; Medical Devices—Guidance on the Application of ISO 14971. Part 2: Machine Learning in Artificial Intelligence—Under Development, a Draft Is Being Reviewed by the Committee. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/87600.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on Medical Devices, Amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and Repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/745/oj/eng (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Veyron, J.H.; Deparis, F.; Al Zayat, M.N.; Belmin, J.; Havreng-Théry, C. Postimplementation Evaluation in Assisted Living Facilities of an eHealth Medical Device Developed to Predict and Avoid Unplanned Hospitalizations: Pragmatic Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e55460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karakoyun, T.; Podhaisky, H.P.; Frenz, A.K.; Schuhmann-Giampieri, G.; Ushikusa, T.; Schröder, D.; Zvolanek, M.; Lopes Da Silva Filho, A. Digital Medical Device Companion (MyIUS) for New Users of Intrauterine Systems: App Development Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e24633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Atee, M.; Hoti, K.; Hughes, J.D. A Technical Note on the PainChek™ System: A Web Portal and Mobile Medical Device for Assessing Pain in People with Dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- The White House. US GOV. Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence. 23 January 2025. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/removing-barriers-to-american-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Government of Canada. Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (Pending Bill C-27). 2022. Available online: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/innovation-better-canada/en/artificial-intelligence-and-data-act (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence and Amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Government of, UK, Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. AI Regulation: A Pro-Innovation Approach. 3 August 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-regulation-a-pro-innovation-approach (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Australia Government, National Artificial Intelligence Centre. Voluntary AI Safety Standard. Guiding Safe and Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence in Australia. 5 September 2024. Available online: https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/voluntary-ai-safety-standard (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Shah, S.F.H.; Arecco, D.; Draper, H.; Tiribelli, S.; Harriss, E.; Matin, R.N. Ethical implications of artificial intelligence in skin cancer diagnostics: Use-case analyses. Br. J. Dermatol. 2025, 192, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Späth, J.; Sewald, Z.; Probul, N.; Berland, M.; Almeida, M.; Pons, N.; Le Chatelier, E.; Ginès, P.; Solé, C.; Juanola, A.; et al. Privacy-Preserving Federated Survival Support Vector Machines for Cross-Institutional Time-To-Event Analysis: Algorithm Development and Validation. JMIR AI 2024, 3, e47652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zawati, M.H.; Lang, M. Does an App a Day Keep the Doctor Away? AI Symptom Checker Applications, Entrenched Bias, and Professional Responsibility. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e50344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wongvibulsin, S.; Yan, M.J.; Pahalyants, V.; Murphy, W.; Daneshjou, R.; Rotemberg, V. Current State of Dermatology Mobile Applications with Artificial Intelligence Features. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 646–650, Erratum in JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 688. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1011. Erratum in JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 688. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alfano, L.; Malcotti, I.; Ciliberti, R. Psychotherapy, artificial intelligence and adolescents: Ethical aspects. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2024, 64, E438–E442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouellette, S.; Rao, B.K. Usefulness of Smartphones in Dermatology: A US-Based Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matin, R.N.; Dinnes, J. AI-based smartphone apps for risk assessment of skin cancer need more evaluation and better regulation. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1749–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pashkov, V.M.; Harkusha, A.O.; Harkusha, Y.O. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Practice: Regulative Issues and Perspectives. Wiad. Lek. 2020, 73, 2722–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Martin, N.; Kreitmair, K. Ethical Issues for Direct-to-Consumer Digital Psychotherapy Apps: Addressing Accountability, Data Protection, and Consent. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ebad, S.A.; Alhashmi, A.; Amara, M.; Miled, A.B.; Saqib, M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Software as a Medical Device (AI-SaMD): A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, G.; Jain, A.; Araveeti, S.R.; Adhikari, S.; Garg, H.; Bhandari, M. FDA-Approved Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices: An Updated Landscape. Electronics 2024, 13, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDCG 2025-6—Interplay Between the Medical Devices Regulation & In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation and the Artificial Intelligence Act (June 2025). Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/latest-updates/mdcg-2025-6-faq-interplay-between-medical-devices-regulation-vitro-diagnostic-medical-devices-2025-06-19_en (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Butcher, C.J.; Hussain, W. Digital healthcare: The future. Future Healthc. J. 2022, 9, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. 2019 Global Health Care Outlook Shaping the Future. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/gr/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/perspectives/2019-global-life-sciences-health-care-outlook.html (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- IQVIA. Digital Health Trends 2021: Innovation Evidence Regulation Adoption. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/digital-health-trends-2021 (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Gál, É.; Ștefan, S.; Cristea, I.A. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; Cuijpers, P.; Carlbring, P.; Messer, M.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Lin, W.; Wen, J.; Chen, G. Impact and efficacy of mobile health intervention in the management of diabetes and hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.; Gallagher, S.; Andrews, T.; Ashall-Payne, L.; Humphreys, L.; Leigh, S. The effectiveness of digital health technologies for patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2022, 3, 936752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretschneider, M.P.; Kolasińska, A.B.; Šomvárska, L.; Klásek, J.; Mareš, J.; Schwarz, P.E. Evaluation of the Impact of Mobile Health App Vitadio in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e68648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qin, M.; Chen, B.; Sun, S.; Liu, X. Effect of mobile phone app-based interventions on quality of life and psychological symptoms among adult cancer survivors: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e39799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Xiong, C.; Yan, J. Effectiveness of mobile health-based self-management interventions in breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 2853–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloeckl, R.; Spielmanns, M.; Stankeviciene, A.; Plidschun, A.; Kroll, D.; Jarosch, I.; Schneeberger, T.; Ulm, B.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Koczulla, A.R. Smartphone application-based pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2025, 80, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iribarren, S.J.; Cato, K.; Falzon, L.; Stone, P.W. What is the economic evidence for mHealth? A systematic review of economic evaluations of mHealth solutions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Ming, W.K.; You, J.H. The cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions on the management of cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Socio-Economic Impact of mHealth: An Assessment Report for the European Union. 2013. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/iot/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Socio-economic_impact-of-mHealth_EU_14062013V2.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Jacob, C.; Sanchez-Vazquez, A.; Ivory, C. Understanding clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: A qualitative review of the most used frameworks. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e18072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.; Sezgin, E.; Sanchez-Vazquez, A.; Ivory, C. Sociotechnical factors affecting patients’ adoption of mobile health tools: Systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e36284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, Q. A review of the quality and impact of mobile health apps. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyzy, M.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Bai, L.; Frey, A.L.; Carracedo, J.M.; Daly, R.; Leigh, S. Don’t judge a book or health app by its cover: User ratings and downloads are not linked to quality. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliunaite, I.; van Gestel, L.; Hoogendoorn, P.; Adriaanse, M. Value of a quality label and European healthcare professionals’ willingness to recommend health apps: An experimental vignette study. J. Health Psychol. 2025, 30, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlhausen, F.; Zinner, M.; Bieske, L.; Ehlers, J.P.; Boehme, P.; Fehring, L. Physicians’ attitudes toward prescribable mHealth apps and implications for adoption in Germany: Mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e33012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European mHealth Hub. D2.1 Knowledge Tool 1: Health Apps Assessment Frameworks. Available online: https://promisalute.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/D2.1-KT1-Health-Apps-Assessment-Frameworks.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Hoogendoorn, P.; Versluis, A.; van Kampen, S.; McCay, C.; Leahy, M.; Bijlsma, M.; Bonacina, S.; Bonten, T.; Bonthuis, M.J.; Butterlin, A.; et al. What makes a quality health app-developing a global research-based health app quality assessment framework for CEN-ISO/TS 82304-2: Delphi study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e43905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, A.L.; Phillips, B.; Baines, R.; McCabe, A.; Elmes, E.; Yeardsley-Pierce, E.; Wall, R.; Parry, J.; Vose, A.; Hewitt, J.; et al. Domain coverage and criteria overlap across digital health technology quality assessments: A systematic review. Health Technol. 2024, 15, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llebot, C.B.; Hoogendoorn, P.; Villalobos-Quesada, M.; Pratdepàdua, B.C. Integration of CEN ISO/TS 82304-2 for existing health authorities? App assessment frameworks: A comparative case study in Catalonia. JMIR mHealth uHealth Forthcom. 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/78182.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- ISO/TS 82304-2:2021; Health and Wellness Apps—Quality and Reliability. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- IEC 82304-1:2016; Health Software—General Requirements for Product Safety. IEC Webstore: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO/IEC 42001:2023; Information Technology—Artificial Intelligence—Management Systems. JTC 1: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 13485:2016; Medical Devices—Quality Management Systems—Requirements for Regulatory Purposes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 14971:2019; Medical Devices—Application of Risk Management to Medical Devices. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. JTC 1: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO/IEEE 11073-40101:2022; Health Informatics—Device Interoperability—Cybersecurity—Vulnerability Assessment Processes. JTC 1: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC/TR 80002-1:2009; Medical Device Software—Guidance on Applying ISO 14971 to Software. IEC Webstore: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- AAMI TIR 34971:2023; Application of ISO 14971 to Machine Learning in AI. Available online: https://webstore.ansi.org/standards/aami/aamitir349712023?srsltid=AfmBOopTNvxB0WFMnuVoZnYyQImwvUeP6X6X0fyZXAdQBC0cDL_BuG72 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- FG-AI4H DEL2.2:2022; Good Practices for Health Applications of AI. Available online: https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-t/opb/fg/T-FG-AI4H-2022-2-PDF-E.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Hasan, M.M.; Phu, J.; Wang, H.; Sowmya, A.; Kalloniatis, M.; Meijering, E. OCT-based diagnosis of glaucoma and glaucoma stages using explainable machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Phu, J.; Wang, H.; Sowmya, A.; Meijering, E.; Kalloniatis, M. Predicting visual field global and local parameters from OCT measurements using explainable machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Focus Area | Mobile Health Terms | AI Terms | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| General AI in mHealth | “mobile health”, “mHealth”, “app *”, “smartphone” | “artificial intelligence”, “AI” | Broad capture of AI applications in mHealth |

| Machine Learning applications | “mobile health”, “mHealth”, “app *”, “smartphone”, “wearable devices” | “machine learning”, “ML”, “supervised learning”, “unsupervised learning” | Predictive analytics and automated decision-making |

| Deep Learning & Neural Networks | “mobile health”, “mHealth”, “app *”, “smartphone” | “deep learning”, “neural networks”, “CNN”, “RNN” | Advanced AI algorithms for clinical or monitoring purposes |

| Telemedicine & Remote Monitoring | “mobile health”, “mHealth”, “app *”, “smartphone”, “telemedicine”, “remote monitoring” | “AI”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “neural networks”, “CNN”, “RNN”, “predictive analytics”, “decision support” | Enhancing patient management and chronic disease monitoring |

| Specific Clinical Domains | “mobile health”, “mHealth”, “app *”, “smartphone”, “mobile apps” | “AI”, “machine learning”, “deep learning” + disease terms (e.g., “diabetes”, “cardiovascular disease”, “mental health”) | Targeted retrieval for specific disease areas |

| Criterion | Definition | Inclusion | Exclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Type | Type of publication | Reviews, with priority to Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses | Original research, Case reports, Technical notes | Ensures high level of evidence |

| Clinical/Bioengineering Relevance | Application in health or bioengineering | mHealth interventions with AI for chronic disease management, telemedicine, mental health, rehabilitation | Purely computational studies, algorithm benchmarking, data architecture without clinical/translational outcomes | Focus on real impact in clinical practice |

| Temporal Scope | Publication period | Studies up to 31 July 2025 | Studies outside this period | Updated post-pandemic coverage |

| Language | Language | English | Non-English | International accessibility and reproducibility |

| Study Focus | Main content | AI applications with tangible clinical/translational value | Technical-only AI methods without healthcare relevance | Maintains focus on clinical narrative |

| Ref. | Description | Focus | Contribution of mHealth and AI | Target Domain | Observed Patterns/Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] Patel J et al. | This review evaluates predictive artificial intelligence approaches used in mobile health platforms to forecast mental health symptoms among youth. It synthesizes how smartphone and wearable data, such as usage patterns, sleep, and physical activity, have been leveraged in predictive models to detect depression, anxiety, and stress. The study highlights both the promise of precision prediction and challenges including small sample sizes and privacy concerns that should be addressed in future work. | Predicting mental health symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress) using AI and mHealth tools. | Real-time monitoring of mental health; supports precision prevention strategies | Mental health (youth, 13–25) | Predictive AI models; mental health monitoring; youth-focused interventions |

| [22] Manyazewal T et al. | This study reviews innovative technologies, including AI and mobile health solutions, aimed at addressing neglected tropical diseases in African settings with ongoing sociopolitical instability. It discusses how these tools support disease surveillance, diagnosis, and intervention in contexts with limited healthcare infrastructure. The review emphasizes feasibility and adaptation of technological approaches in unstable and low-resource environments. | Use of AI, mobile apps, and other technologies for NTD prevention, diagnosis, and management amidst instability. | Supports NTD surveillance and treatment; AI aids in outbreak prediction and intervention planning | Neglected tropical diseases | AI for outbreak prediction; mHealth for disease management; low-resource and unstable regions |

| [23] Thakuria T et al. | This review examines the use of deep learning for early diagnosis of oral cancer via smartphone and DSLR image analysis. It highlights the role of convolutional neural networks in improving classification accuracy for early detection tasks. The study also discusses challenges such as data quality and limited annotated datasets, while noting the potential for accessible screening tools in low-resource settings. | Deep learning (CNN) applications for early oral cancer diagnosis using smartphone and DSLR imaging. | AI-based tools improve diagnostic accuracy; enhances accessibility of screening | Oral cancer diagnosis | Deep learning for image-based diagnosis; diagnostic accuracy improvements; potential for low-resource deployment |

| [24] Förstel M et al. | This review investigates features used in machine learning models to forecast patient arrival numbers in healthcare settings. It focuses on various predictor types, including non-temporal data such as weather and internet usage patterns, to enhance forecasting accuracy. The study highlights how these models can support operational planning, reducing prediction errors and improving resource allocation in clinical environments. | Machine learning feature identification for forecasting patient arrivals using non-temporal predictors. | ML forecasting aids operational planning; highlights value of diverse non-temporal features | Healthcare operations | Operational optimization via ML; non-clinical healthcare AI use; feature exploration beyond temporal data |

| [25] Chau RC et al. | This review discusses the potential of self-monitoring oral health using smartphone selfies powered by artificial intelligence for preventive dentistry. It evaluates how AI-enabled oral health tools can detect dental conditions and support early prevention by reducing plaque and gingival indices. The synthesis notes positive short-term outcomes and suggests areas requiring further research on long-term behavioral change and oral health awareness. | AI-enhanced self-monitoring of oral health via smartphone images and selfies. | Supports early detection of oral health issues; facilitates preventive dental care; reduces plaque and gingival indices | Preventive dentistry | AI for self-monitoring; smartphone-based diagnostic support; early prevention strategies |

| [26] Fu Y et al. | This systematic review evaluates smartphone-based hand function assessment tools that leverage artificial intelligence. It focuses on how sensor data from mobile devices can objectively measure hand mobility and performance, potentially improving rehabilitation and clinical assessment. The study highlights the strengths of combining smartphone sensors with automated analysis while noting gaps in standardization and clinical validation. | Smartphone-based assessment of hand function using AI and sensor data. | Provides objective measurement of hand function; enhances rehabilitation assessment; supports remote monitoring | Hand function assessment | Sensor data integration; AI-driven functional evaluation; clinical assessment support |

| [27] Negi S et al. | This umbrella review synthesizes evidence on artificial intelligence applications for dental caries diagnosis and detection. It explores a range of models and techniques used to identify caries from dental images and clinical data, summarizing diagnostic performance and limitations. The review underscores the promise of AI in improving diagnostic accuracy while calling for further validation across diverse populations. | AI for dental caries diagnosis and detection across imaging and clinical datasets. | Improves diagnostic accuracy; supports early detection workflows; highlights need for broader validation | Dental caries diagnosis | Diagnostic AI models; image and data fusion techniques; clinical applicability and validation needs |

| [28] Lange M et al. | This review identifies approaches for using AI in workplace health promotion and prevention, focusing on how digital tools can support occupational wellbeing. It synthesizes evidence on predictive models and interventions that address physical activity, stress management, and healthy behaviours. The study highlights opportunities and challenges for implementing AI-driven workplace health solutions across diverse occupational settings. | AI in workplace health promotion and preventive interventions. | Supports health behaviour monitoring; predictive models for stress and activity; enhances occupational health strategies | Workplace health promotion | AI for behavioural health support; digital intervention trends; organizational implementation |

| [29] Chow SM et al. | This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the effectiveness of mHealth apps on adherence to and symptoms from oral anticancer medications. It evaluates how mobile applications influence medication adherence, symptom reporting, and clinical outcomes. Results indicate that mHealth interventions can improve adherence and reduce symptom burden, although study heterogeneity suggests the need for standardized outcomes. | Effectiveness of mHealth apps on adherence and symptoms for oral anticancer medications. | Improves medication adherence; reduces symptom burden; supports patient engagement | Oral anticancer treatment adherence | mHealth for adherence support; symptom tracking; patient engagement trends |

| [30] Jin K et al. | This systematic review examines how smartphone technology integrated with artificial intelligence is used in advanced ophthalmic care. It synthesizes evidence from 52 studies on screening, disease detection, telemedicine, and patient management across major ocular conditions. The review emphasizes improvements in diagnostic performance and accessibility, while noting challenges related to data privacy, algorithm validation, and real-world implementation. | Integration of smartphone technology and AI to improve ophthalmic diagnosis, screening, telemedicine, and patient care. | Enhances early detection and monitoring of eye diseases; supports remote patient management; improves accessibility in underserved areas | Ophthalmic care and eye disease management | AI-driven smartphone imaging; tele-ophthalmology enhancement; accessibility and diagnostic performance improvements |

| [31] Choi A et al. | This review assesses digital phenotyping methods using smartphone sensors to detect behavioral patterns associated with stress, anxiety, and mild depression in nonclinical adult populations. It highlights evidence that passive sensing, such as GPS, accelerometer, and phone usage patterns, can identify correlates of mild mental health symptoms. The study also addresses challenges such as sensor accuracy, privacy concerns, and individual behavioral variability across contexts. | Digital phenotyping via smartphone sensors for detecting stress, anxiety, and mild depression. | Identifies behavioral patterns linked to mental health using smartphone data; highlights effective passive sensors; discusses ethical and technical challenges | Behavioral mental health monitoring | Passive sensing for behavioral markers; sensor pattern associations with mental health; privacy and technical limitations |

| [32] Segur-Ferrer J et al. | This scoping review and thematic analysis identifies methodological frameworks and key dimensions to be considered in digital health technology assessment (DHTA). It synthesizes frameworks used to evaluate digital health technologies, including metrics related to clinical effectiveness, usability, economic impact, and ethical considerations. The review highlights the need for comprehensive, multidimensional assessment approaches to support robust evaluation and regulatory decisions. | Frameworks and dimensions for assessing digital health technologies, including AI and mobile health tools. | Clarifies assessment criteria for digital health technologies; highlights clinical, usability, economic, and ethical dimensions; guides structured evaluation practices | Digital health technology assessment | Multidimensional evaluation criteria; methodological framework synthesis; implications for regulatory and policy decisions |

| [33] Giunti G et al. | This review explores the co-creation of an automated mHealth apps systematic review process using generative AI within a design science research framework. It discusses how AI-enabled tools can assist in automating literature screening, data extraction, and synthesis tasks. The study highlights the potential of generative AI to enhance efficiency and consistency in systematic review workflows while considering design challenges in human–AI collaboration. | Use of generative AI to automate components of systematic review processes for mHealth apps. | Shows generative AI supporting automation of review screening and extraction; enhances efficiency and consistency of review workflows; discusses human–AI cooperation design | Review process automation | Generative AI for review automation; human–AI collaboration challenges; efficiency improvements in evidence synthesis |

| [34] Pala D et al. | This review examines smartphone applications designed to support nutrition, focusing on target outcomes and core functionalities. It synthesizes evidence on app features such as dietary tracking, personalized feedback, and behavior change support. The study discusses how apps influence nutritional outcomes and user engagement, as well as limitations related to evidence quality and long-term adherence. | Functionality and outcomes of nutrition support smartphone applications. | Offers dietary tracking and personalized feedback; supports behavior change and nutritional monitoring; highlights engagement features | Nutrition support via mobile apps | Personalized nutrition feedback; behavior change support; functionality outcome mapping |

| [35] Jahan E et al. | This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates smartphone applications aimed at preventing type 2 diabetes through lifestyle change support. It assesses outcomes related to weight management, physical activity, dietary behaviors, and metabolic indicators. The findings suggest that mHealth apps can contribute to diabetes prevention through structured interventions and continuous user engagement. | Smartphone apps for prevention of type 2 diabetes through lifestyle modification. | Promotes physical activity and dietary change; facilitates continuous engagement; supports metabolic outcome improvements | Type 2 diabetes prevention | Lifestyle modification support; engagement and adherence trends; preventive health impact |

| [36] Gheisari M et al. | This multidimensional systematic review examines mobile apps for COVID-19 detection and diagnosis, focusing on their potential use in pandemic control and future outbreak management. It synthesizes evidence on app functionalities, diagnostic performance, and integration with public health monitoring systems. The review highlights opportunities and limitations in using mobile tools for pandemic preparedness and response. | Mobile apps for COVID-19 detection and diagnosis and implications for future pandemic control. | Supports disease surveillance and early detection; integrates diagnostic functions with public health data; highlights limitations and future needs | Pandemic detection and control | Diagnostic surveillance via apps; pandemic preparedness relevance; integration with public health infrastructure |

| [37] Tomlin HR et al. | This review identifies challenges and opportunities for professional medical publication writers to contribute to plain language summaries (PLS) within AI/ML research environments. It discusses barriers related to interpretability, accuracy, and audience comprehension, and highlights strategies to improve the quality of PLS. The study emphasizes the role of clear communication in translating complex AI/ML evidence for diverse stakeholders. | Challenges and opportunities in creating plain language summaries in an AI/ML research context. | Highlights interpretability and communication barriers; suggests strategies for improving PLS quality; addresses stakeholder engagement in evidence translation | Health communication and AI/ML interpretation | Plain language science communication; stakeholder comprehension trends; role of writers in AI evidence translation |

| [38] Xue J et al. | This scoping review evaluates the current state of chatbots in digital health, examining their functionalities, applications, and potential benefits. It synthesizes evidence on how conversational agents support health information, triage, patient engagement, and self-management. The study discusses both opportunities and limitations, including accuracy, user trust, and integration with clinical workflows. | Evaluation of chatbot technologies in digital health contexts. | Supports health information delivery and triage; enables patient engagement and self-management; discusses challenges with trust and clinical integration | Digital health chatbots | Conversational AI applications; engagement and triage support; trust and workflow integration |

| [39] He X et al. | This scoping review identifies existing barriers faced by direct-to-consumer AI healthcare apps and provides recommendations for future design improvements. It highlights issues such as usability, transparency, data privacy, and regulatory compliance that limit adoption. The review emphasizes the need to address these challenges to enhance user trust and app effectiveness in everyday healthcare. | Barriers and design recommendations for direct-to-consumer AI healthcare applications. | Identifies usability and transparency challenges; highlights privacy and regulatory issues; offers design recommendations for future apps | Direct-to-consumer AI healthcare apps | Usability and trust barriers; privacy and regulatory considerations; future design directions |

| [40] Sumner J et al. | This systematic review evaluates AI applications in physical rehabilitation, examining availability, clinical effects, and implementation barriers. Evidence spans app-based systems, robotic devices, gaming systems, and wearables used to restore function, improve physical activity, or assist recovery. The review highlights mixed clinical effects and identifies challenges such as technology literacy, reliability issues, and user fatigue, while noting potential improvements in access and remote monitoring. | AI applications in physical rehabilitation to support recovery and functional outcomes. | AI-enhanced systems for rehabilitation tasks; supports remote monitoring and access to programmes; reduces manpower requirements | Physical rehabilitation | Diverse AI solutions (robotics, wearables); mixed clinical effectiveness; implementation and usability barriers |

| [41] Bendotti et al. | This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses conversational AI interventions for smoking cessation, focusing on their effectiveness compared with standard care or no intervention. It synthesizes evidence from RCTs using chatbots and dialogue systems across apps, social media, and web platforms. Results indicate promising benefits for sustained tobacco abstinence, though high heterogeneity and study bias suggest cautious interpretation. | Conversational AI for supporting smoking cessation outcomes. | Conversational AI increases likelihood of quitting smoking; chatbots emulate personalised support; highlights engagement and behavioural support | Smoking cessation support | AI for behaviour change support; mobile conversational agents; engagement and intervention heterogeneity |

| [42] Pyper et al. | This scoping review examines digital health technologies using patient-generated data for real-world clinical outcome measurement. It highlights frameworks and use cases where mobile tools complement clinical assessments, addressing challenges like data quality, integration, and interpretability. The review underscores potential for personalised healthcare decision-making. | Digital health technologies leveraging patient-generated data for clinical outcome measurement. | Uses mobile and digital tools to capture real-world health data; supports objective outcome measurement; highlights integration and interpretability challenges | Patient-generated outcome measurement | Real-world data integration; mobile data for outcomes; challenges in data quality and clinical integration |

| [43] Hasan et al. | This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates smartphone-based AI systems for diabetic retinopathy detection. Evidence on sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic performance shows potential for early identification, especially in low-resource settings. Limitations include data diversity, algorithm generalisability, and need for rigorous clinical validation. | Diagnostic accuracy of smartphone-based AI systems for diabetic retinopathy detection. | AI improves early detection accuracy; facilitates screening in non-specialist settings; highlights validation and generalisability needs | Diabetic retinopathy diagnosis | Smartphone AI for imaging diagnosis; accessibility in low-resource settings; need for broader validation |

| [44] Chatterjee et al. | This systematic review and knowledge mapping explores ICT-based remote and automatic COVID-19 patient monitoring and care. It highlights mobile apps, telemonitoring systems, and automated alerts used for tracking symptoms, vital signs, and care coordination. The review discusses opportunities and limitations, including data integration, user acceptance, and scalability. | ICT-based remote and automatic monitoring and care for COVID-19 patients. | Mobile and digital tools for remote symptom tracking; supports care coordination and alerting; highlights scalability and integration challenges | COVID-19 remote patient monitoring | Remote monitoring trend; ICT and mobile integration; pandemic-driven innovation |

| [45] Fegan & Hutchinson | This short review examines the potential of mobile technology to address early childhood caries. It discusses current interventions, smartphone-enabled dental monitoring, and preventive strategies. The article emphasizes the need for stronger evidence and standardized methodologies for real-world prevention. | Exploration of mobile technology’s role in reducing early childhood caries. | Suggests mobile tools for dental health monitoring; encourages preventive strategies; notes need for rigorous validation | Early childhood caries prevention | Mobile dental monitoring concepts; preventive focus; need for stronger evidence |

| [46] Koumpouros et al. | This systematic review investigates mobile applications for pain management, covering commercial and research efforts integrating AI or computational support. It synthesizes evidence on app features, usability, and outcomes related to tracking pain, adherence, and self-help resources. Limitations include diversity of approaches, standardization, and clinical validation. | Pain management mobile applications integrating AI and supportive technologies. | Supports pain tracking and self-management; offers therapeutic guidance and reminders; highlights usability and evidence gaps | Pain management via mobile apps | Self-management trend; pain tracking features; usability and validation limitations |

| [47] Duarte et al. | This systematic review evaluates digital clinical tools for screening or diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea. It synthesizes evidence on tool performance, including sensitivity, specificity, and feasibility across care settings. The review highlights opportunities for earlier detection and streamlined diagnostics, along with challenges in data quality, patient adherence, and integration. | Digital clinical tools and AI in screening and diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. | Enhances early detection of sleep apnea; supports diagnostic workflows; notes challenges in real-world integration | Obstructive sleep apnea screening and diagnosis | AI clinical tool trend; diagnostic accuracy focus; adoption challenges |

| [48] Lin et al. | This systematic assessment examines conversational agents for mental health and well-being, focusing on scope, characteristics, behaviour change techniques, and app quality. It highlights how these apps use dialogue and interaction patterns to support mental health outcomes, including cognitive behavioural strategies. Limitations in sustaining long-term mental health improvements are also discussed. | Conversational agents for mental health and well-being, including behaviour change and engagement. | Supports mental health engagement via chatbots; integrates behaviour change techniques; evaluates quality and engagement metrics | Conversational mental health support | Behaviour change focus; conversational AI engagement; quality variability |

| [49] Moharrami et al. | This systematic review evaluates AI algorithms for detecting dental caries on oral photographs, assessing diagnostic accuracy, methodology, and data sources. Evidence shows promising performance for screening and early detection, though limitations include dataset bias and the need for validation across diverse populations. | AI for detecting dental caries from oral photographs and imaging data. | AI enhances dental caries detection accuracy; supports early screening and decision support; highlights dataset and validation needs | Dental caries detection via photography | Imaging AI for dentistry; diagnostic screening trend; validation and bias issues |

| [50] Piendel et al. | This review provides an update on mobile applications that collect data among adults with or at risk of Alzheimer’s disease, focusing on passive and active data collection relevant to cognitive changes. It synthesizes evidence on how smartphone apps can monitor daily routines and behaviors that may indicate subtle cognitive decline, with potential utility for early detection and screening. The review also discusses limitations in current app validation and privacy issues, noting that widespread implementation remains underdeveloped despite promising feasibility. | Mobile applications collecting data for cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease screening. | Passively and actively collects cognitive data; potential early detection and screening support; highlights privacy and validation concerns | Cognitive health screening and Alzheimer’s risk | Passive and active data tracking; cognitive change monitoring; screening tool feasibility |

| [51] Lam et al. | This systematic review examines applications of markerless motion capture (MMC) technology for clinical measurement in rehabilitation, highlighting its potential to track movement without physical markers. It summarizes studies where MMC has been applied to identify and measure movement patterns in various patient populations, with focuses on clinical utility and feasibility. The review notes that although the approach shows promise for rehabilitation assessments, evidence on clinical effectiveness and integration with AI models remains preliminary and requires further development. | Markerless motion capture technology applied to clinical movement measurement in rehabilitation. | Avoids need for physical markers; tracks movement kinematics; potential integration with AI for screening | Rehabilitation movement analysis | MMC for clinical assessment; motion tracking innovations; preliminary evidence and integration needs |

| [52] Sumra et al. | This systematic review evaluates smartphone apps designed for domestic violence prevention, focusing on features and effectiveness of mobile tools addressing safety, reporting, and support. It synthesizes evidence on how these apps facilitate emergency response, risk assessment, and access to resources for individuals at risk of domestic violence. The study highlights the range of functionalities offered and notes gaps in empirical evaluation and standardized outcome measurement for these prevention technologies. | Smartphone apps for domestic violence prevention and support. | Supports emergency reporting and risk assessment; provides safety resources and guidance; notes evaluation and outcome measure gaps | Domestic violence prevention | Safety and reporting functions; support resource access; need for standardized evaluation |