Effects of Salt Stress on Earthworm Function and Compost Quality During Vermicomposting of Kitchen Wastes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Analysis of the Physicochemical Properties in Vermicomposting Production

2.3.2. Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.3.3. Earthworm Intestinal Content Extraction and Mucus Extraction

2.3.4. Determination of Catalase and Superoxide Dismutase Activities

2.3.5. DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.3.6. Statistical Analysis and Data Visualization

3. Results and Discussion

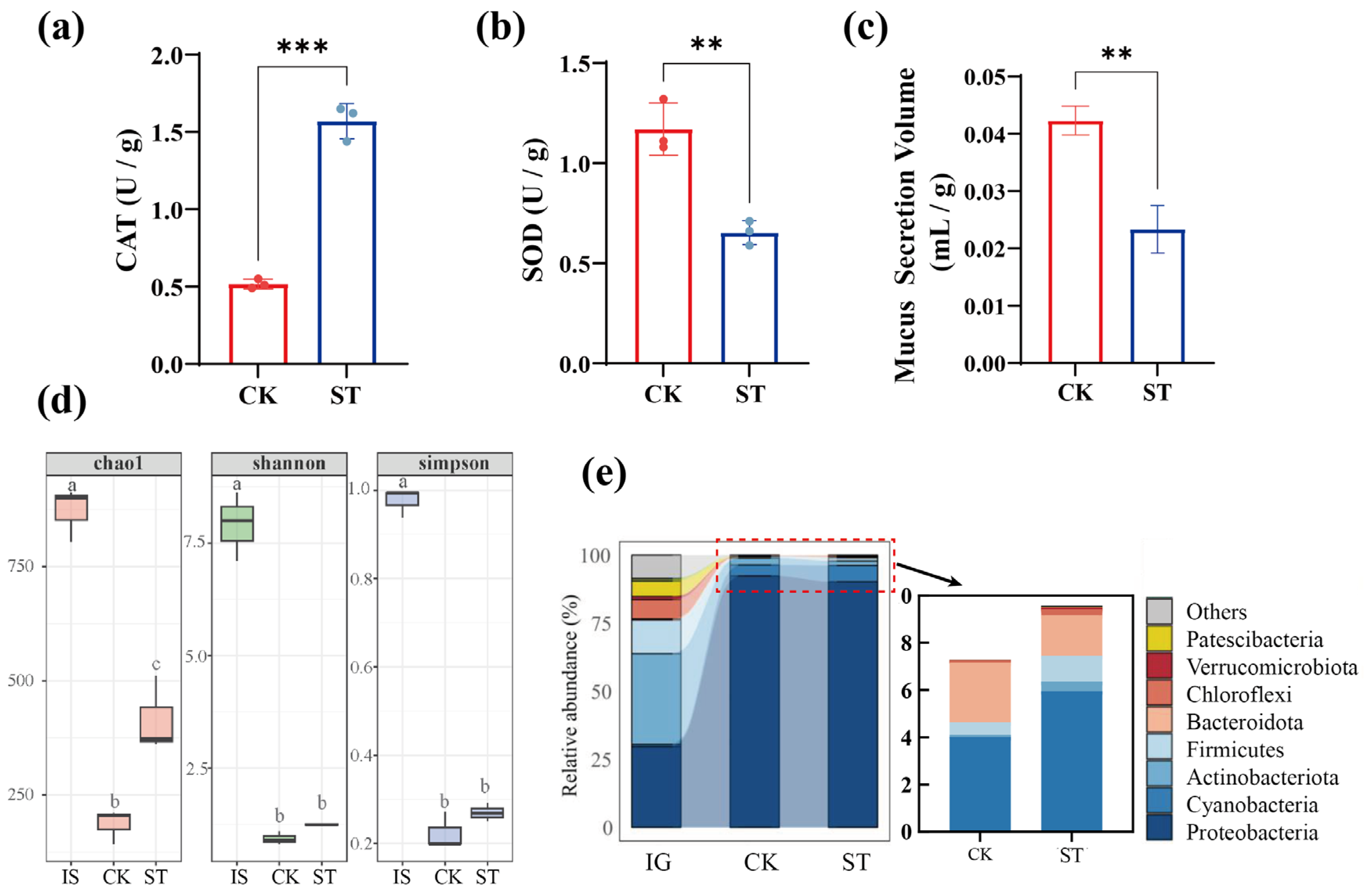

3.1. Effects of Salt Stress on the Physiological Characteristics of Earthworms

3.1.1. Impact on Earthworm Biomass

3.1.2. Impact on Intestinal Microbiota

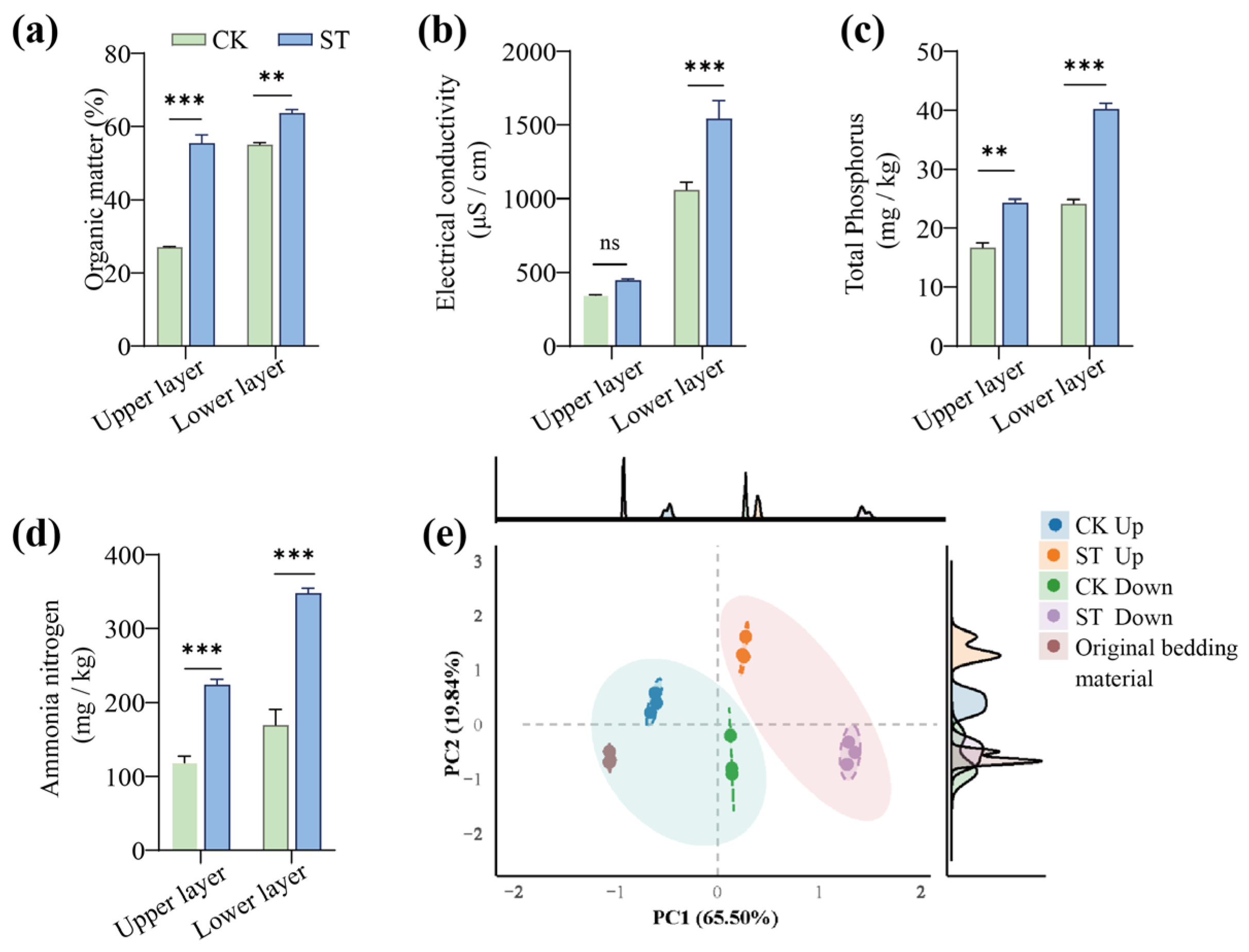

3.2. Effects of Salt Stress on Substrate Characteristics

3.2.1. Impact on Physicochemical Properties of the Upper and Lower Layers

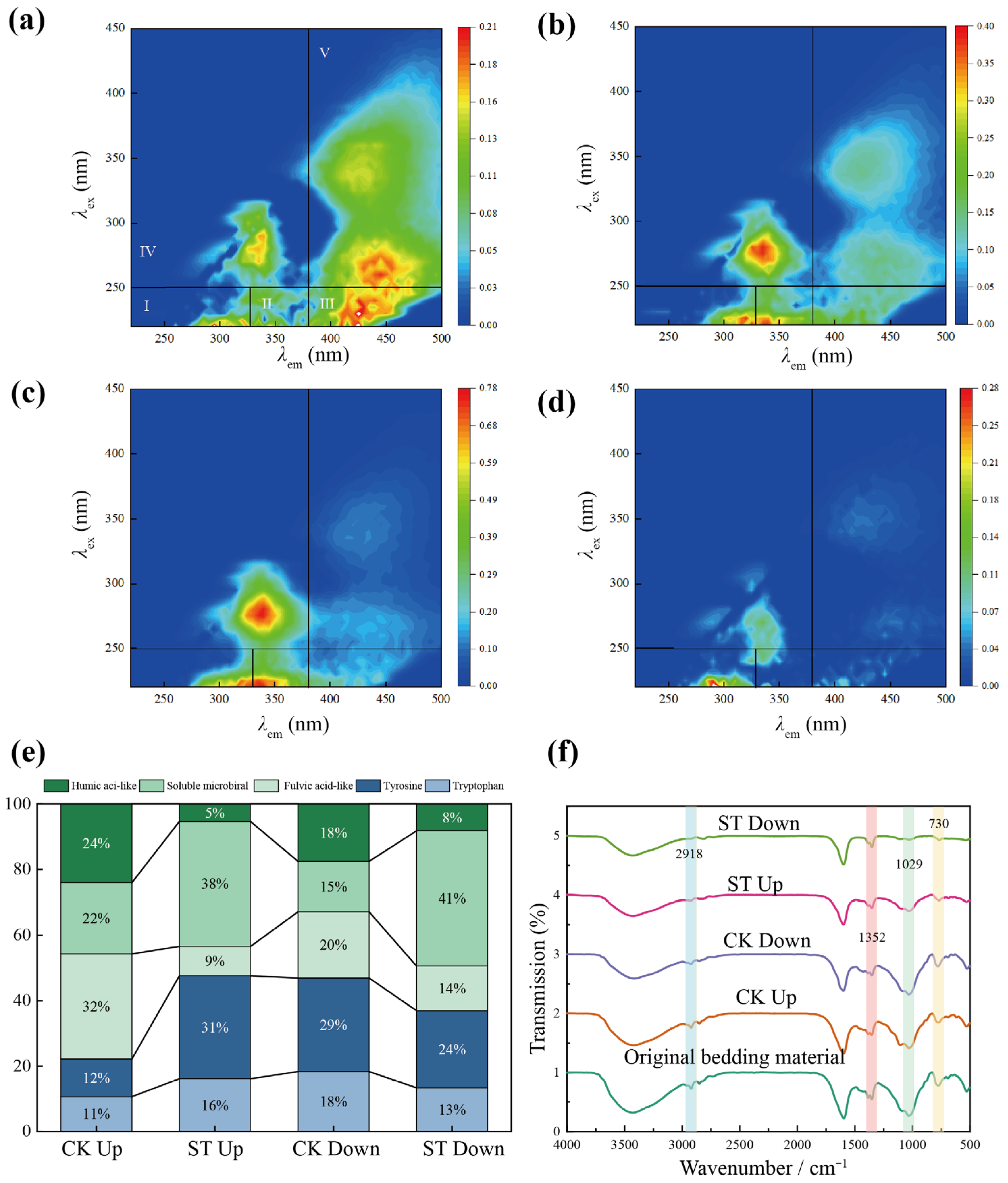

3.2.2. Effects of Salt Stress on the Humification of Organic Matter

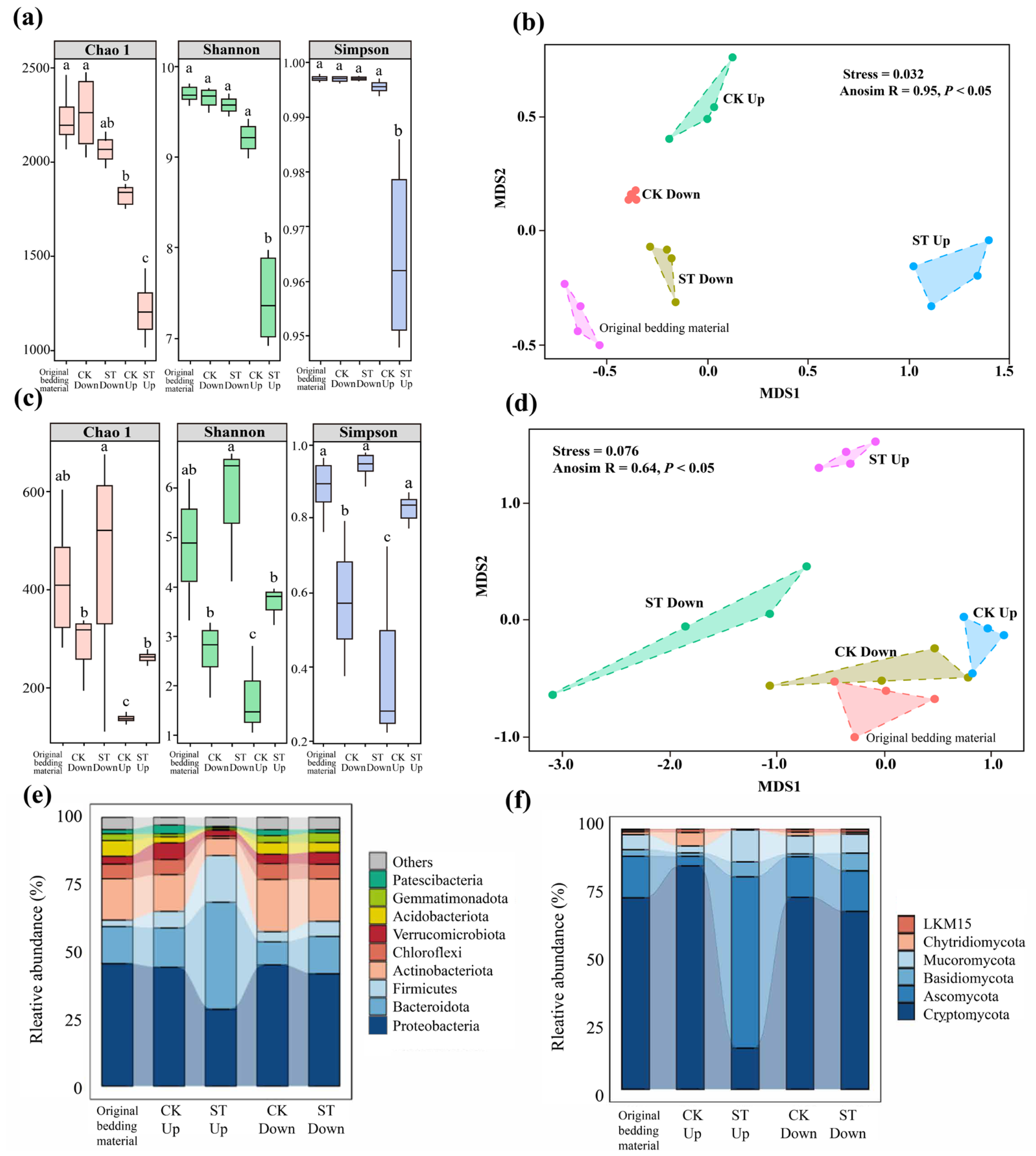

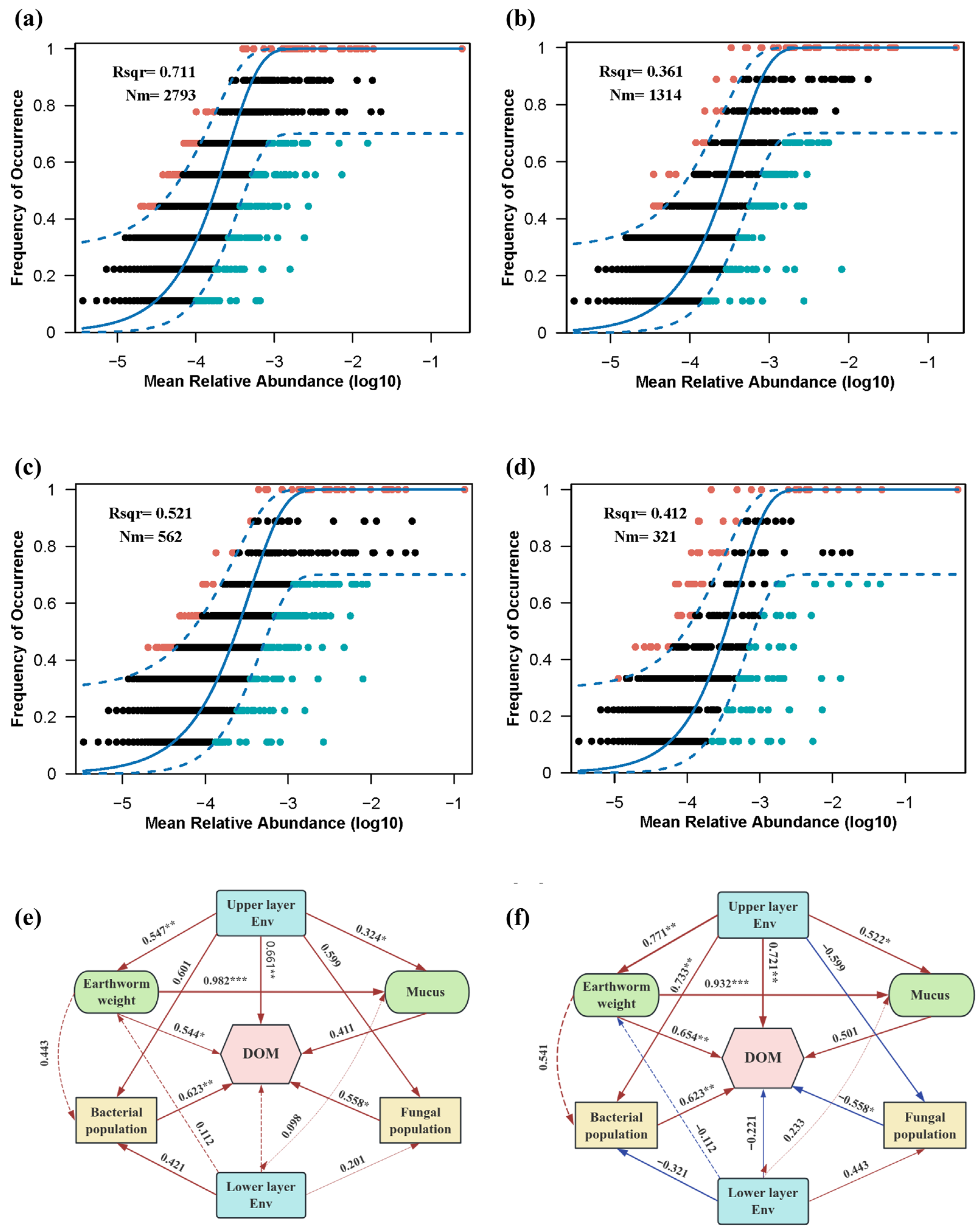

3.2.3. Effects of Salt Stress on the Microbial Communities in the Substrate

3.3. Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Salt Stress on the the Vermicomposting System

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ST | Salt Treatment |

| KW | Kitchen waste |

| CK | Control group |

References

- Ding, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.W.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, J.; Shao, Z.; Iris, C.; Pan, B.; Li, X. A review of China’s municipal solid waste (MSW) and comparison with international regions: Management and technologies in treatment and resource utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126144.1–126144.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Wei, X. Extraction methods, physiological activities and high value applications of tea residue and its active components: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 12150–12168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Synergistic effects of economic benefits, resource conservation and carbon mitigation of kitchen waste recycling from the perspective of carbon neutrality. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2023, 199, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.; Aira, M.; Kolbe, A.R.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Pérez-Losadaz, M. Changes in the composition and function of bacterial communities during vermicomposting may explain beneficial properties of vermicompost. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, Z.; Guan, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, D. A comprehensive review on food waste anaerobic co-digestion: Current situation and research prospect. Process. Saf. Environ. 2023, 179, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Huang, W.; Huang, K.; Yang, R.; Li, T.; Mao, H. Effects of salt content on degradation and transformation performance of kitchen waste during vermicomposting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, F.; Zheng, S.; Zeng, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Kang, L. Soil ecosystem multifunctionality and growth characteristics of Leymus chinensis were enhanced after sandy soil amendment with vermicompost and soil conditioner in soil-plant-microbe system. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, K.G.; Abu-Hussien, S.H. Root Rot Management in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Through Integrated Biocontrol Strategies using Metabolites from Trichoderma harzianum, Serratia marcescens, and Vermicompost Tea. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, R.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ouyang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, T. Effects of exogenous additives on thermophilic co-composting of food waste digestate: Coupled response of enhanced humification and suppressed gaseous emissions. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Hodson, M.E.; Hu, C.-J.; Li, W.-J.; Li, J.; Monroy, A.B.; Tong, L.; Xiao, X. Combined toxicity of polyethylene microplastics and soil salinization to earthworms is generally antagonistic or additive. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiesi, F.; Motaghian, H.R.; Nazarizadeh, M. The sublethal lead (Pb) toxicity to the earthworm Eisenia fetida (Annelida, Oligochaeta) as affected by NaCl salinity and manure addition in a calcareous clay loam soil during an indoor mesocosm experiment. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Zhao, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, B.; Ding, H. Vermicompost and Azotobacter chroococcum increase nitrogen retention in saline-alkali soil and nitrogen utilization of maize. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2024, 201, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Y.; Wang, Y.-X.; Sha, H.-Q.; Zhou, H.-M.; Sun, Y.; Su, J.; Mei, Y.; Dai, X.; He, X.-S. The community succession mechanisms and interactive dynamics of microorganisms under high salinity and alkalinity conditions during composting. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 379, 124881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shang, G.; Wang, X. Biochemical, transcriptomic, gut microbiome responses and defense mechanisms of the earthworm Eisenia fetida to salt stress. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.; Deb, U.; Barman, S.; Das, S.; Sundar Bhattacharya, S.; Fai Tsang, Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, K.-H. Appraisal of lignocellusoic biomass degrading potential of three earthworm species using vermireactor mediated with spent mushroom substrate: Compost quality, crystallinity, and microbial community structural analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 135215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling and function. Mol. Cell. 2021, 81, 3691–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Huang, K.; Huang, W.; Wang, B.; Shi, J.; Xia, H.; Li, F. Bacterial dispersal enhances the elimination of active fecal coliforms during vermicomposting of fruit and vegetable wastes: The overlooked role of earthworm mucus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Ma, F.; Yang, D.; You, Y. Earthworm and arbuscular mycorrhiza interactions: Strategies to motivate antioxidant responses and improve soil functionality. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 272, 115980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Fang, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Transcriptome, bioaccumulation and toxicity analyses of earthworms (Eisenia fetida) affected by trifloxystrobin and trifloxystrobin acid. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265 Pt B, 115100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Bai, Y.; Zha, L.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, H.; Shah, S.R.H.; Sun, H.; Zhang, C. Mechanism of the Gut Microbiota Colonization Resistance and Enteric Pathogen Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 716299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.R.; Condron, L.M.; Clough, T.J.; Fiers, M.; Stewart, A.; Hill, R.A.; Sherlock, R.R. Biochar induced soil microbial community change: Implications for biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus. Pedobiologia 2011, 54, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Chapuis-Lardy, L.; Razafimbelo, T.; Razafindrakoto, M.; Blanchart, E. Endogeic earthworms shape bacterial functional communities and affect organic matter mineralization in a tropical soil. ISME J. 2012, 6, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, F.; Lu, F.; Yang, L.; Li, T. Cultivation of earthworms and analysis of associated bacterial communities during earthworms’ growth using two types of agricultural wastes. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Dai, W.; Li, P.; Yao, D.; Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cao, H. Variations in bacterial taxonomic profiles and potential functions in response to the gut transit of earthworms (Eisenia fetida) feeding on cow manure. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Xie, X.; Cui, H.; Wei, Z. Effect of precursors combined with bacteria communities on the formation of humic substances during different materials composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 226, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, N.; Raghav, M.; Dubey, S.; Bedi, N. Bacterial Exopolysaccharides: Insight into Their Role in Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouni, Y.; Ghnaya, T.; Montemurrob, F.; Abdellya, C.; Lakhdar, A. The role of humic substances in mitigating the harmful effects of soil salinity and improve plant productivity. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2014, 3, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Guan, M.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Xia, H.; Li, Y. Biochars modify the degradation pathways of dewatered sludge by regulating active microorganisms during gut digestion of earthworms. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, A.; Lanzetta, R.; Parrilli, M.; Corsaro, M. Exopolysaccharides from Marine and Marine Extremophilic Bacteria: Structures, Properties, Ecological Roles and Applications. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeoma, B.C.; Ekeoma, L.N.; Yusuf, M.; Haruna, A.; Ikeogu, C.K.; Merican, Z.M.A.; Kamyab, H.; Pham, C.Q.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Chelliapan, S. Recent advances in the biocatalytic mitigation of emerging pollutants: A comprehensive review. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 369, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Bravo Vazquez, L.A.; Mora Hernandez, E.O.; Moreno Becerril, M.Y.; Oza, G.; Ahmed, S.S.S.J.; Ramalingam, S.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Green remediation potential of immobilized oxidoreductases to treat halo-organic pollutants persist in wastewater and soil matrices—A way forward. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučerík, J.; Šmejkalová, D.; Čechlovská, H.; Pekař, M. New insights into aggregation and conformational behaviour of humic substances: Application of high resolution ultrasonic spectroscopy. Org. Geochem. 2007, 38, 2098–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Kim, M.-S.; Ock, G.; Hong, S.; Cho, J.; Shin, K.H.; Hur, J. Estimation of different source contributions to sediment organic matter in an agricultural-forested watershed using end member mixing analyses based on stable isotope ratios and fluorescence spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 618, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Qu, J.H.; Wang, Y.K.; Mai, W.N.; Wan, D.J.; Lu, X.Y. Responses of microbial community and antibiotic resistance genes to co-existence of chloramphenicol and salinity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 7683–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, V.; Squartini, A.; Masi, A.; Sarkar, A.; Singh, R.P. Metabarcoding analysis of the bacterial succession during vermicomposting of municipal solid waste employing the earthworm Eisenia fetida. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 144389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Gan, Z.; Xu, R.; Meng, F. Cellulose-induced shifts in microbial communities and microbial interactions in an anoxic/aerobic membrane bioreactor. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 42, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidou, A.; Gutleben, J.; Versluis, D.; Forgiarini, F.; van Passel, M.W.J.; Ingham, C.J.; Smidt, H.; Sipkema, D. Comparative genomic analysis of Flavobacteriaceae: Insights into carbohydrate metabolism, gliding motility and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammert, H.; Kivistik, C.; Kisand, V.; Käiro, K.; Herlemann, D.P.R. Resistance of freshwater sediment bacterial communities to salinity disturbance and the implication for industrial salt discharge and climate change-based salinization. Front. Microbiomes 2023, 2, 1232571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-H.; Lian, S.-J.; Wang, R.-N.; Zou, H.; Guo, R.-B.; Fu, S.-F. Enhanced anaerobic digestion of food waste by metal cations and mechanisms analysis. Renew. Energy 2023, 218, 119386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, M.; Ye, Z.; Liu, D. Lei bamboo (Phyllostachys praecox) shows greater sensitivity to salt stress than to hypoxia stress: Insights from plant physiology, metabolome and soil microbiome. Plant Soil. 2025, 513, 2395–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xue, H.; Li, Z.; Li, M. Effects of saline-alkali stress on bacterial and fungal community diversity in Leymus chinensis rhizosphere soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 70000–70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Chen, L.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Ning, Q.; Li, W. Mortierella elongata’s roles in organic agriculture and crop growth promotion in a mineral soil. Land Degrad Dev. 2018, 29, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilari, E.; Stanton, C.; Reen, F.J.; Ross, R.P. Uncovering the Biotechnological Importance of Geotrichum candidum. Foods 2023, 12, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Sun, J.; Ji, R.; Min, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, H.; Cheng, S. Crude Oil Biodegradation by a Biosurfactant-Producing Bacterial Consortium in High-Salinity Soil. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.A.S.; Ferreira, P.C.; Pupin, B.; Dias, L.P.; Rangel, D.E.N. Osmotolerance as a determinant of microbial ecology: A study of phylogenetically diverse fungi. Fungal Biol. 2019, 124, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Lei, J.; Han, F.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W. UV-activated peroxymonosulfate assisted heterotrophic ammonium assimilation for high-salinity leachate treatment: Mechanism and performance evaluation. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, N. A novel strategy for high efficiency of anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge by using a Fe-Cu microbial electrolysis method: Performance, electron transfer, key enzymes and microbial community. Water Res. 2025, 287 Pt A, 124322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Bedding Materials | Kitchen Wastes | |

|---|---|---|

| Organic matter (%) | 29.47 ± 0.31 | 94.41 ± 0.51 |

| Water content (%) | 56.42 ± 0.63 | 92.32 ± 0.32 |

| pH | 7.35 ± 0.02 | 5.59 ± 0.28 |

| Electrical conductivity (μS/cm) | 230.5 ± 2.69 | 1911.1 ± 3.22 |

| Nitrate (mg/kg) | 235.65 ± 34.21 | 2303.16 ± 44.26 |

| Total nitrogen (mg/kg) | 767.85 ± 49.92 | 13,655.29 ± 301.35 |

| Total phosphorus (mg/kg) | 0.209 ± 0.046 | 76.93 ± 3.73 |

| Ammonium (mg/kg) | 82.83 ± 4.33 | 13,016.21 ± 441.33 |

| 0 d | 35 d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | Number | Average Weight (g) | Weight (g) | Number | Average Weight (g) | |

| CK | 164.7 | 300 | 0.549 | 169.4 | 305 | 0.555 |

| ST | 172.5 | 300 | 0.575 | 73.5 | 227 | 0.324 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mao, H.; Ding, J.; Huang, W.; Huang, K.; Yang, R. Effects of Salt Stress on Earthworm Function and Compost Quality During Vermicomposting of Kitchen Wastes. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010038

Mao H, Ding J, Huang W, Huang K, Yang R. Effects of Salt Stress on Earthworm Function and Compost Quality During Vermicomposting of Kitchen Wastes. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Hailiang, Jungang Ding, Wenqi Huang, Kui Huang, and Rongchuan Yang. 2026. "Effects of Salt Stress on Earthworm Function and Compost Quality During Vermicomposting of Kitchen Wastes" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010038

APA StyleMao, H., Ding, J., Huang, W., Huang, K., & Yang, R. (2026). Effects of Salt Stress on Earthworm Function and Compost Quality During Vermicomposting of Kitchen Wastes. Bioengineering, 13(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010038