MG-HGLNet: A Mixed-Grained Hierarchical Geometric-Semantic Learning Framework with Dynamic Prototypes for Coronary Artery Lesions Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Difficulty in maintaining long-range anatomical and hemodynamic consistency: The physiological significance of a local stenosis is inherently relative, depending on the global context of the continuous, tortuous vessel tree (e.g., proximal plaque burden and distal reference diameter) rather than isolated local features.

- Difficulty in decoupling the plaque texture from stenosis geometry: Plaque characterization relies on spectral signatures (density), while stenosis grading requires morphological boundary delineation. In CCTA, these features are often visually coupled and degraded by artifacts (e.g., calcium blooming), making them hard to distinguish.

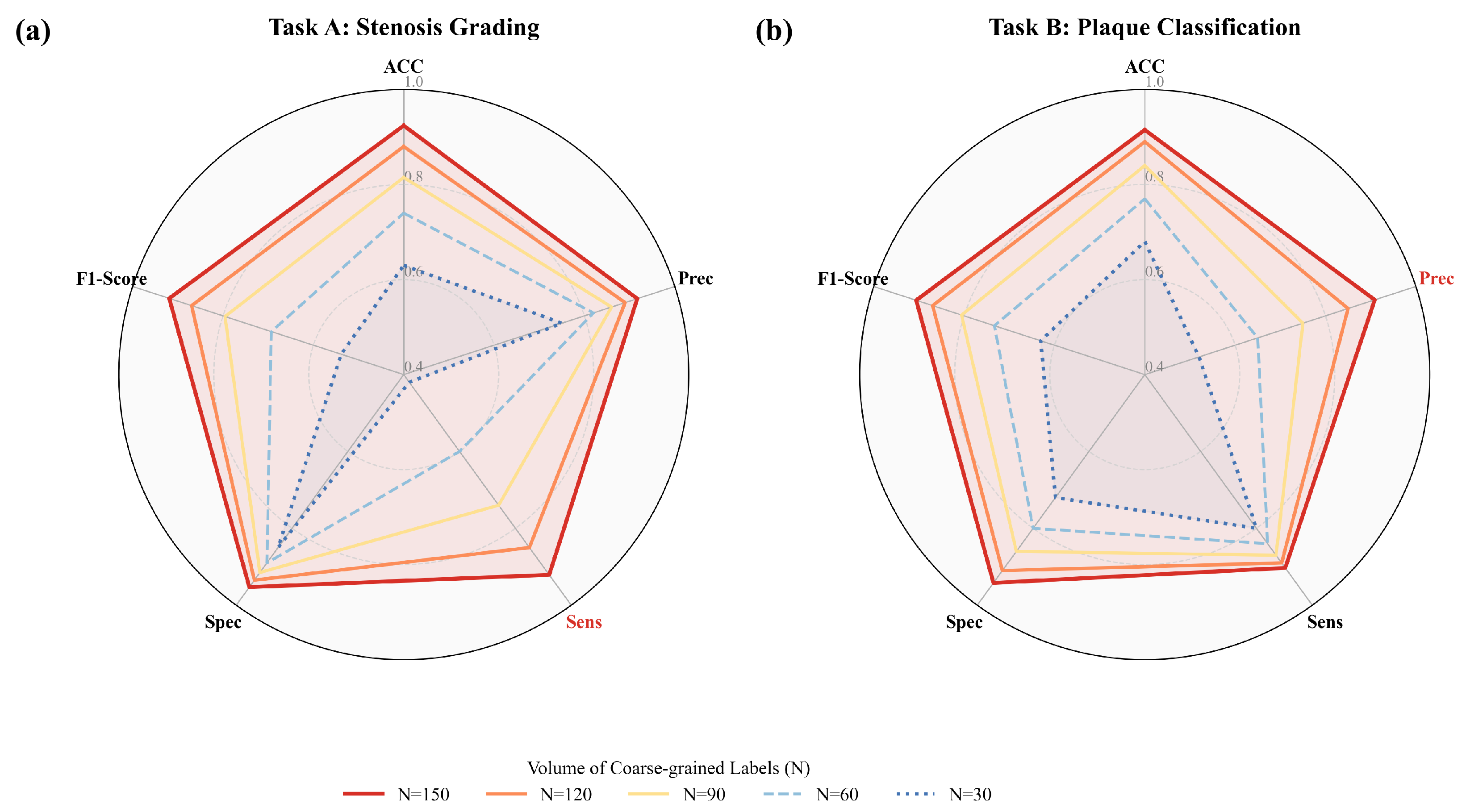

- Insufficiency of fine-grained labels and ambiguity of weak supervision: Obtaining fine-grained segment-level labels is labor-intensive, whereas coarse-grained branch-level labels are readily available. However, there is currently a lack of effective strategies to properly utilize these coarse labels to guide fine-grained feature learning, which may lead to negative optimization of the network due to the use of coarse labels.

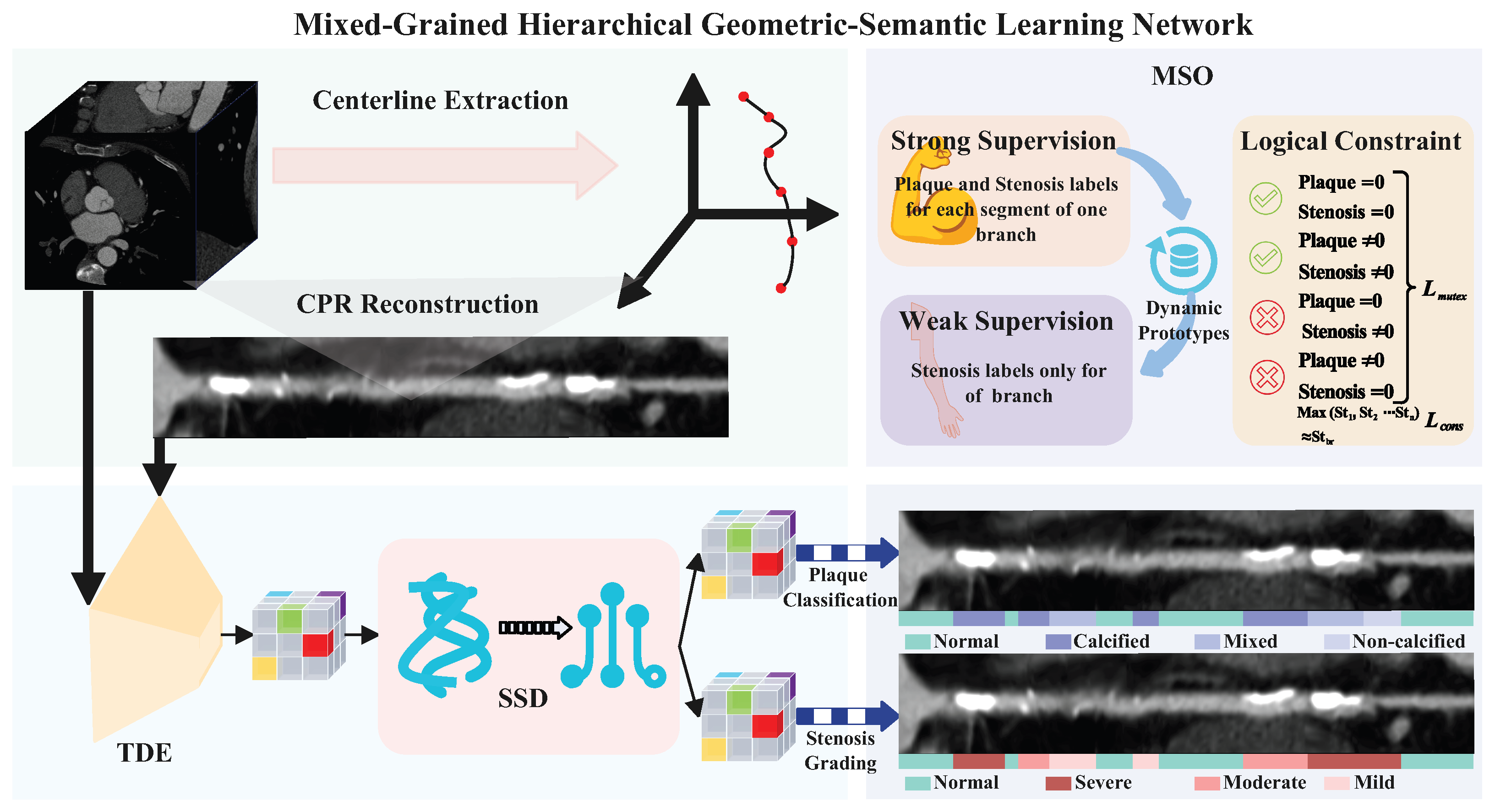

- We propose a novel end-to-end MG-HGLNet for CA lesions assessment. Extensive experiments on an in-house dataset demonstrate that MG-HGLNet achieves state-of-the-art performance in both CA lumen stenosis grading and plaque classification.

- We present a TDE module to effectively capture long-range anatomical dependencies and correct spatial distortions inherent in CPR images.

- We design a SSD module that explicitly decouples plaque texture from stenosis geometry by synergizing spectral analysis with deformable morphological attention, significantly enhancing diagnostic interpretability and accuracy.

- We design a dynamic prototype-based learning strategy that bridges the gap between fine-grained segment annotations and coarse-grained clinical reports. Combined with logical mutual exclusion constraints, this allows for efficient utilization of datasets with coarse-grained labels.

2. Related Works

2.1. Coronary Artery Lesions Assessment

2.2. Mamba in Medical Image Analysis

2.3. Weakly Supervised Learning in Medical Imaging

3. Materials and Methods

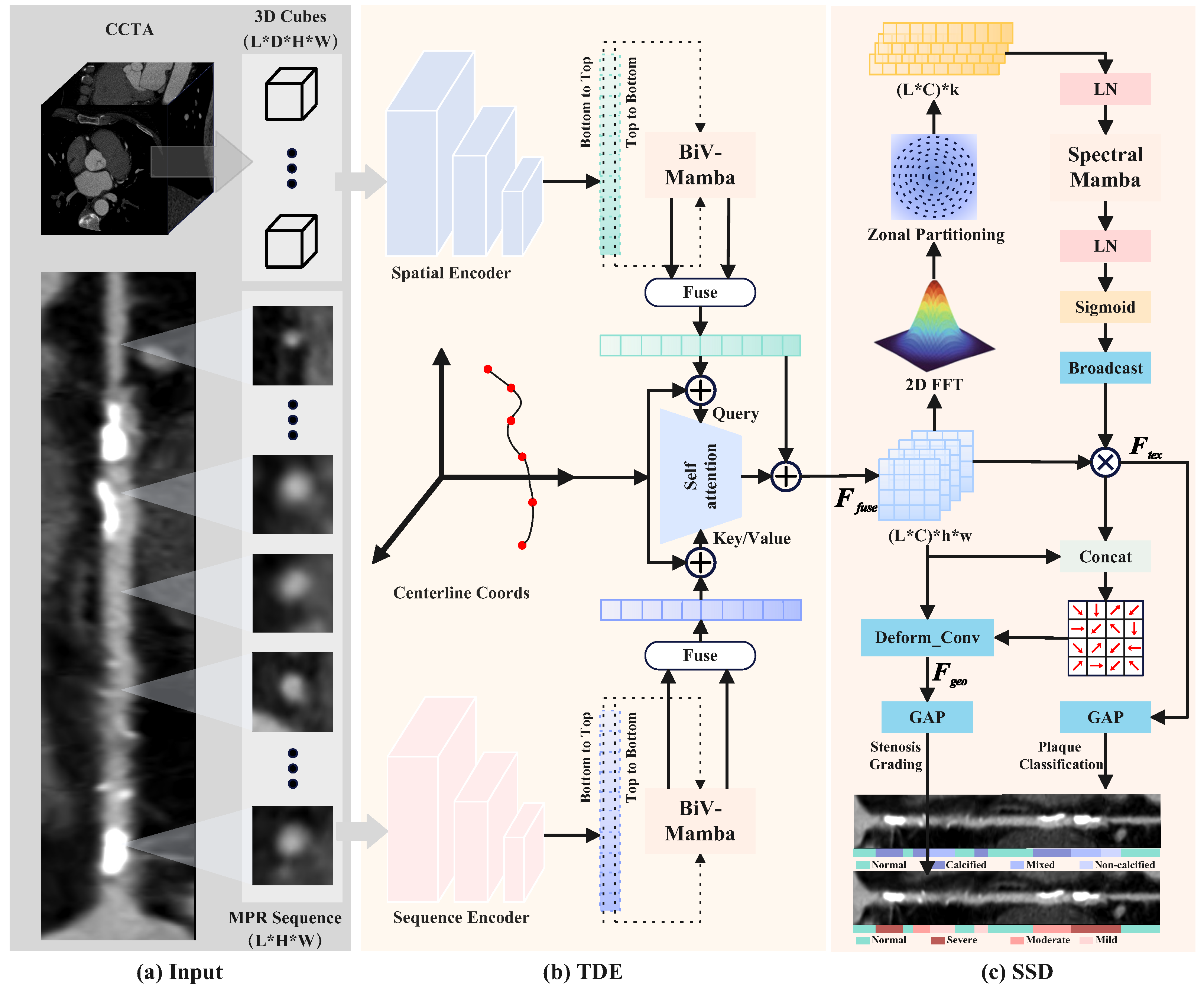

3.1. Topology-Aware Dual-Stream Encoding

3.2. Synergistic Spectral–Morphological Decoupling

3.2.1. Spectral-Aware Texture Refinement

3.2.2. Texture-Guided Morphological Refinement

3.2.3. Task-Specific Diagnostic Projection

3.3. Mixed-Grained Supervision Optimization

3.3.1. Strong Supervision and Prototype Alignment

3.3.2. Weakly-Supervised Learning via Dynamic Prototypes

3.3.3. Logical Regularization and Joint Objective

4. Experiment Configurations

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

5. Results and Analysis

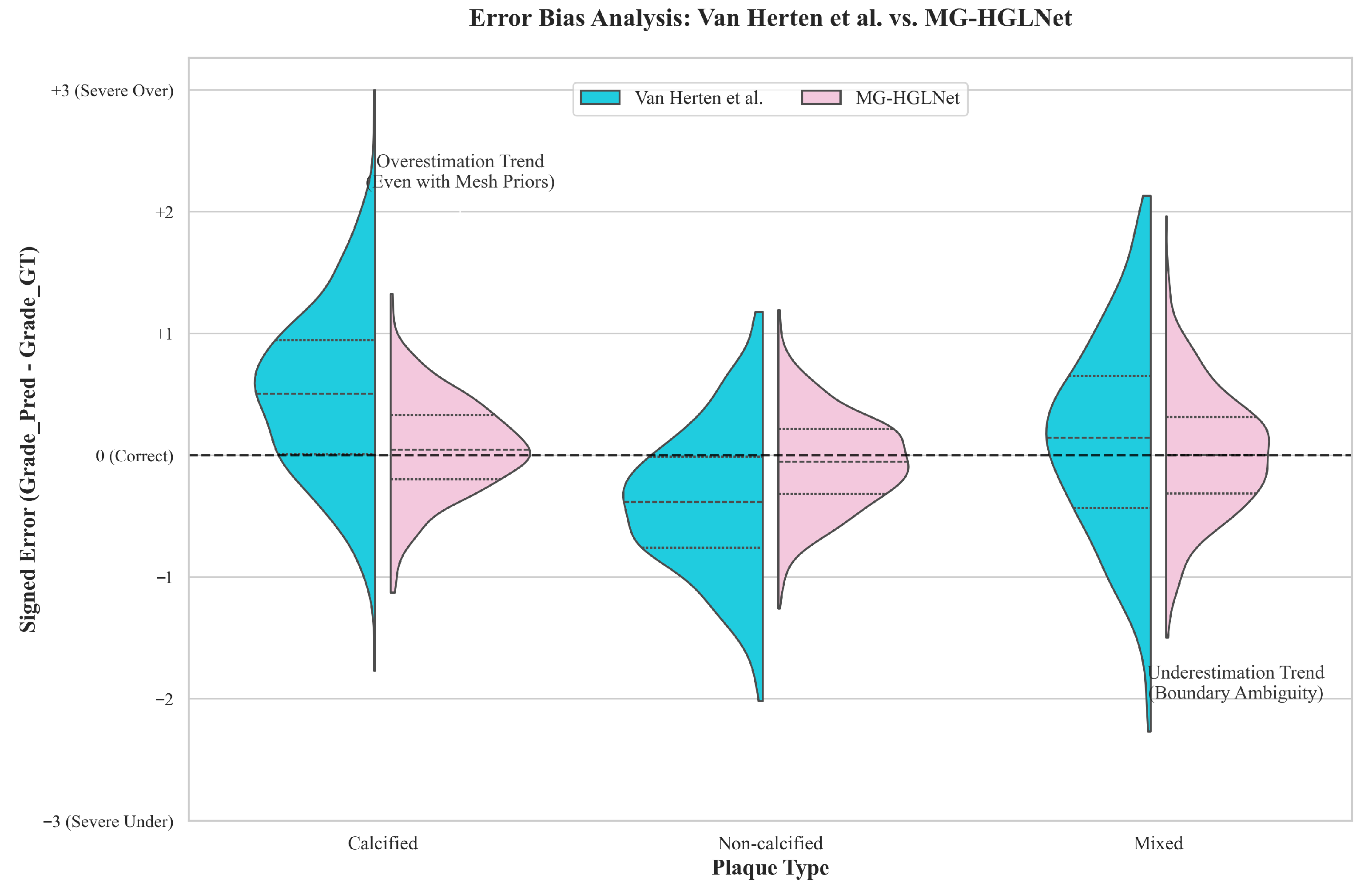

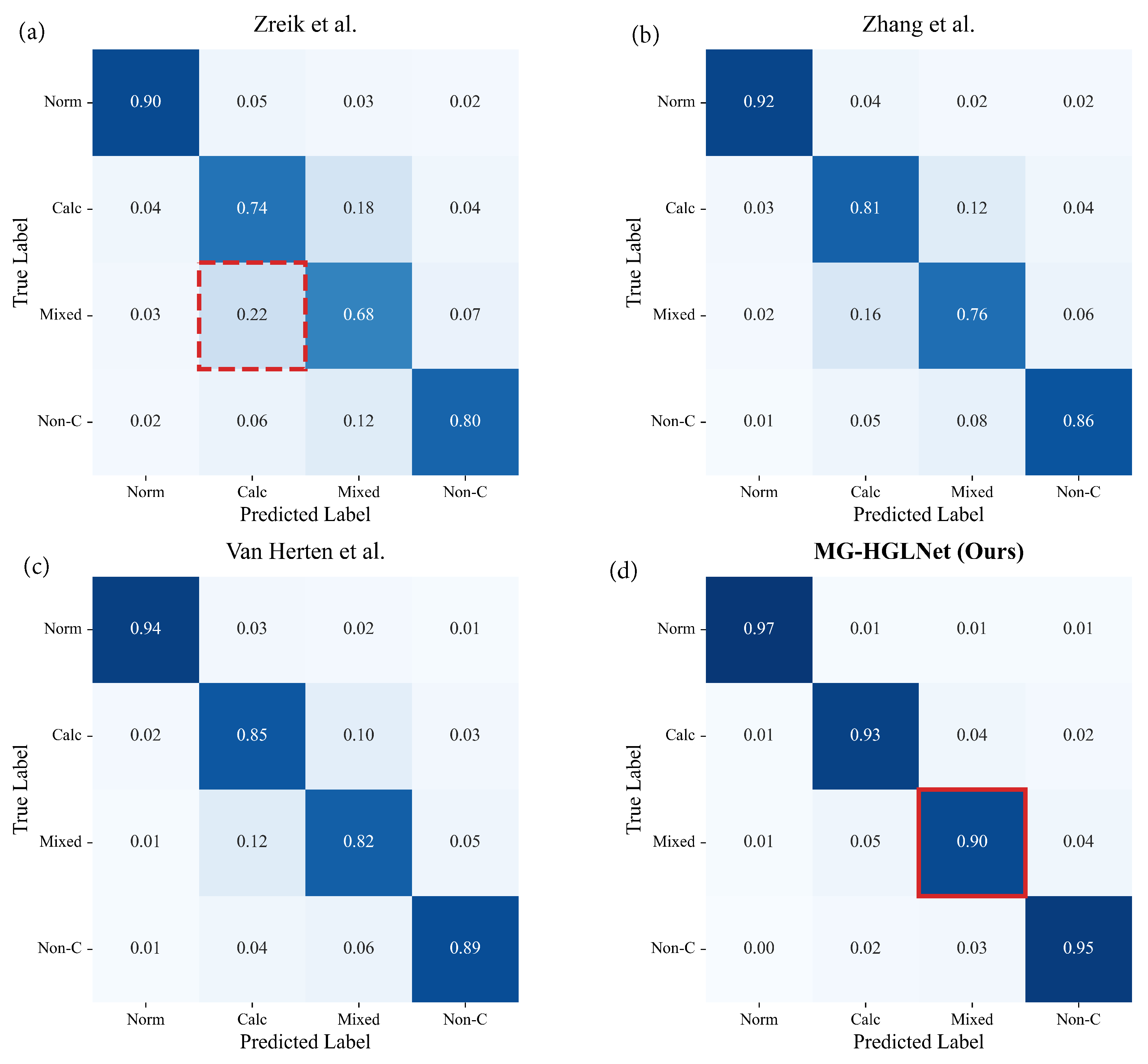

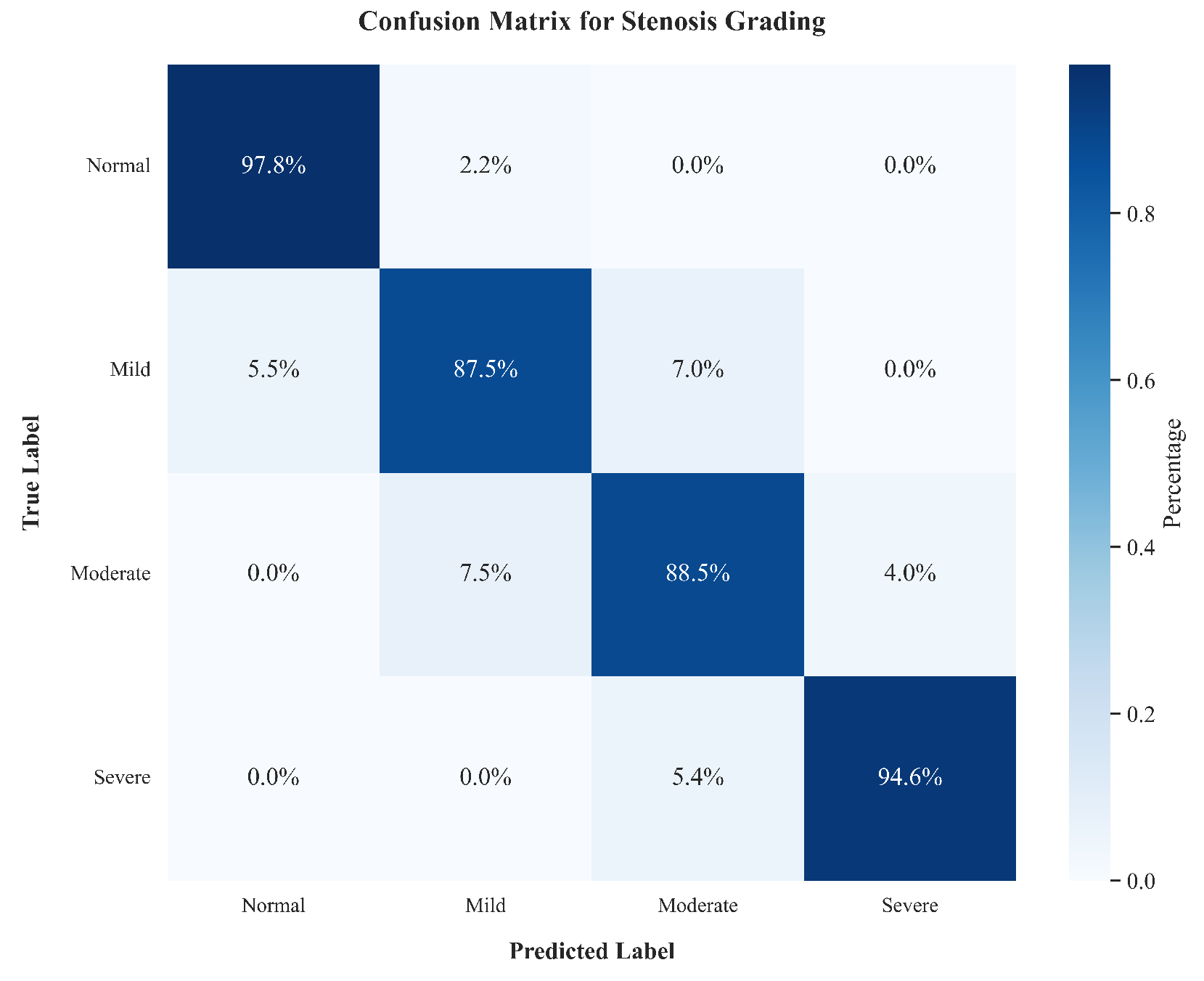

5.1. Comparisons with the State-of-the-Art Methods

5.1.1. Quantitative Results

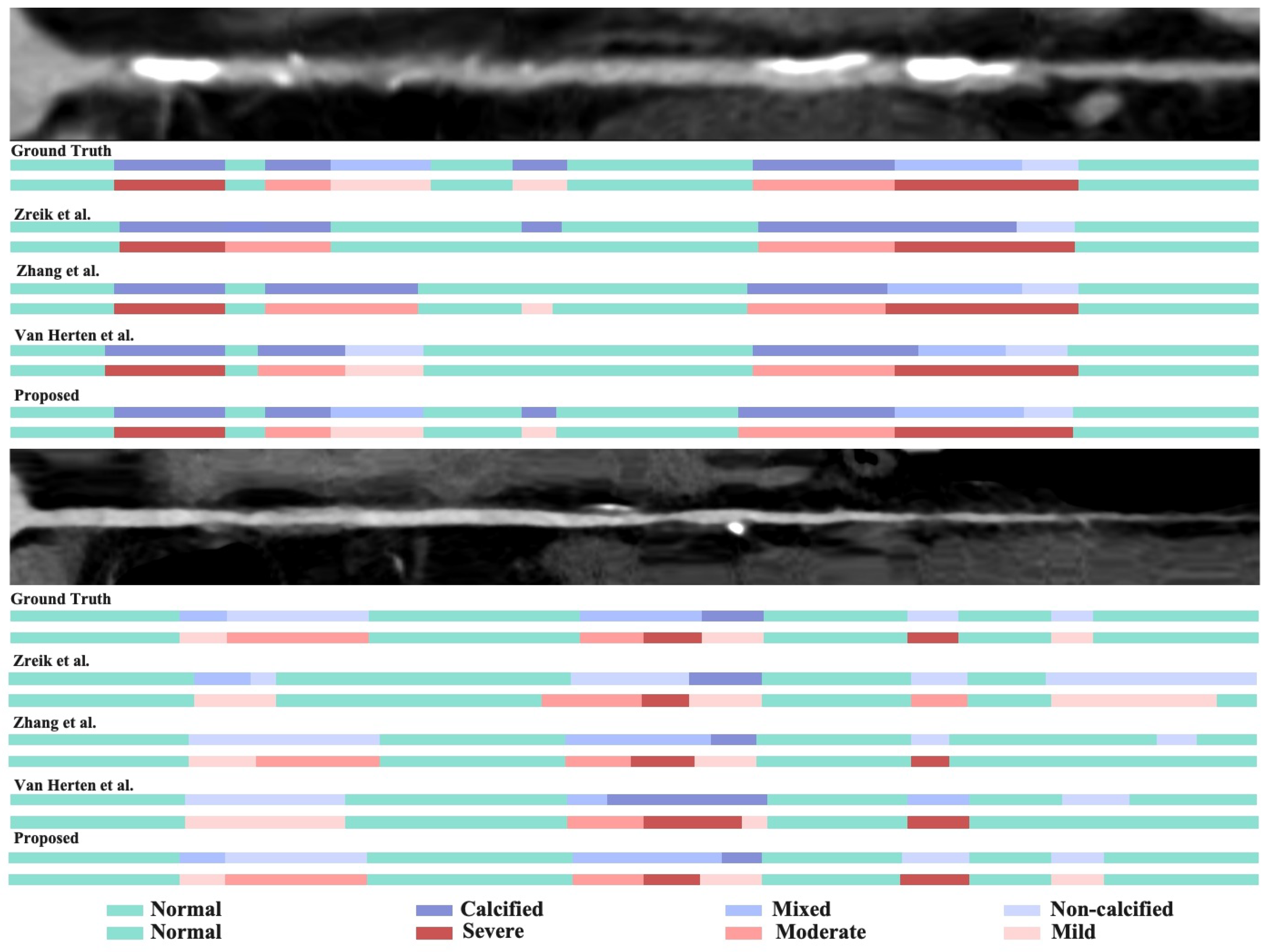

5.1.2. Qualitative Results

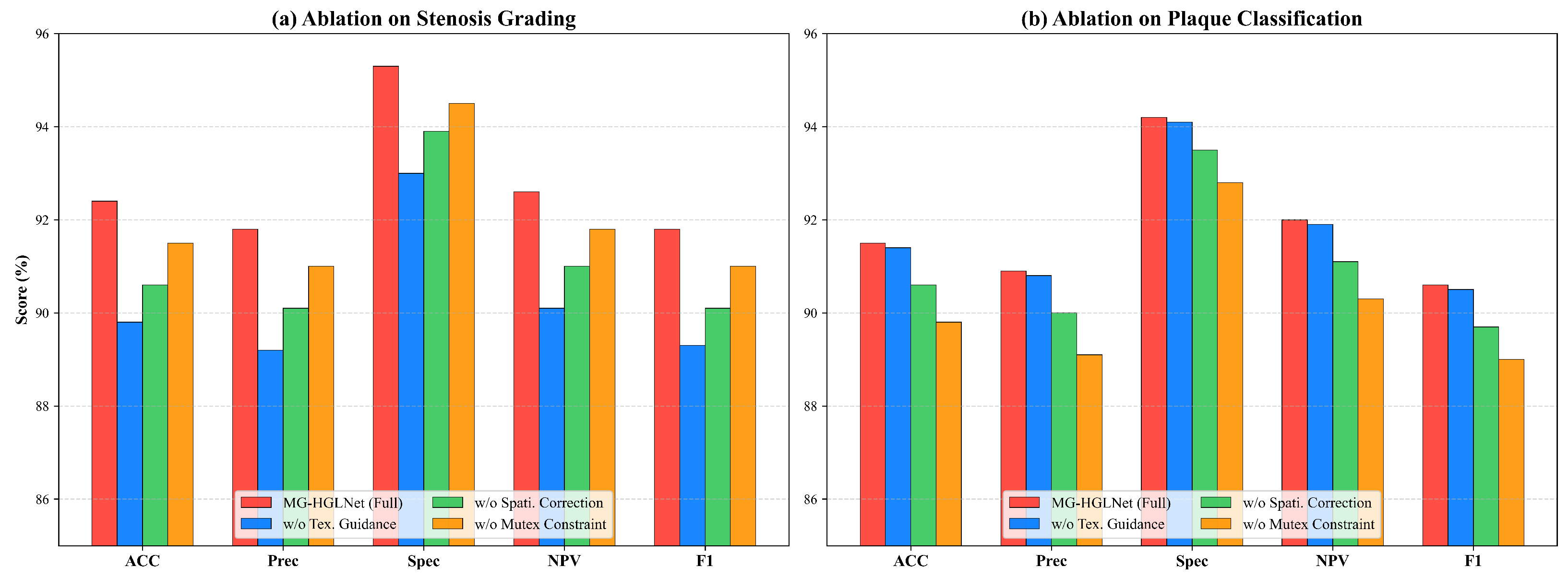

5.2. Ablation Study

5.2.1. Quantitative Comparison of Ablation Study

5.2.2. Qualitative Comparison of Ablation Study

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BiV-Mamba | Bidirectional Vessel Mamba |

| CA | Coronary Artery |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CAD-RADS | Coronary Artery Disease-Reporting and Data System |

| CAMs | Class Activation Maps |

| CCTA | Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography |

| CE | Cross-Entropy |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPR | Curved Planar Reformation |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| EMA | Exponential Moving Average |

| FB-Mamba | Frequency-Band Mamba |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| MG-HGLNet | Mixed-Grained Hierarchical Geometric-Semantic Learning Network |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MPR | Multi-Planar Reformatted |

| MSO | Mixed-Grained Supervision Optimization |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| RCNN | Recurrent Convolutional Neural Network |

| SAM | Spatial-Aware Cross-Attention Module |

| SSD | Synergistic Spectral–Morphological Decoupling |

| SSM | Structured State Space Model |

| TDE | Topology-Aware Dual-Stream Encoding |

| TG-DBA | Texture-Guided Deformable Boundary Attention |

| ViTs | Vision Transformers |

| VSS | Visual State Space |

References

- Collet, C.; Capodanno, D.; Onuma, Y.; Banning, A.; Stone, G.W.; Taggart, D.P.; Sabik, J.; Serruys, P.W. Left main coronary artery disease: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, e93–e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Kotoku, N.; Nørgaard, B.L.; Garg, S.; Nieman, K.; Dweck, M.R.; Bax, J.J.; Knuuti, J.; Narula, J.; Perera, D.; et al. Computed tomographic angiography in coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention 2023, 18, e1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.N.; Lin, A.; Dey, D.; Berman, D.S.; Han, D. Application of Quantitative Assessment of Coronary Atherosclerosis by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography. Korean J. Radiol. 2024, 25, 518–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Guo, N.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Clinical evaluation of the automatic coronary artery disease reporting and data system (CAD-RADS) in coronary computed tomography angiography using convolutional neural networks. Acad. Radiol. 2023, 30, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, R.; Fung, K.; Thai, T.; Moore, K.; Mannel, R.; Liu, H.; Zheng, B.; et al. Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 79, 102444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Yang, L.; Chen, H. Automatic coronary plaque detection, classification, and stenosis grading using deep learning and radiomics on computed tomography angiography images: A multi-center multi-vendor study. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 5276–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristanto, W.; van Ooijen, P.M.; Jansen-van der Weide, M.C.; Vliegenthart, R.; Oudkerk, M. A meta analysis and hierarchical classification of HU-based atherosclerotic plaque characterization criteria. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepis, T.; Marwan, M.; Pflederer, T.; Seltmann, M.; Ropers, D.; Daniel, W.G.; Achenbach, S. Quantification of non-calcified coronary atherosclerotic plaques with dual-source computed tomography: Comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Heart 2010, 96, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreik, M.; Van Hamersvelt, R.W.; Wolterink, J.M.; Leiner, T.; Viergever, M.A.; Išgum, I. A recurrent CNN for automatic detection and classification of coronary artery plaque and stenosis in coronary CT angiography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 38, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzinger, F.; Wels, M.; Breininger, K.; Gülsün, M.A.; Schöbinger, M.; André, F.; Buß, S.; Görich, J.; Sühling, M.; Maier, A. Automatic CAD-RADS scoring using deep learning. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2020, Lima, Peru, 4–8 October 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Zang, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shu, H.; Coatrieux, J.L.; et al. Coronary p-Graph: Automatic classification and localization of coronary artery stenosis from Cardiac CTA using DSA-based annotations. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2025, 123, 102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Fang, X.; Zou, M.; Luo, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, K.; Qiu, Z.; Gao, X.; Li, S. A Trusted Lesion-assessment Network for Interpretable Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease in Coronary CT Angiography. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 6009–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herten, R.L.; Hampe, N.; Takx, R.A.; Franssen, K.J.; Wang, Y.; Suchá, D.; Henriques, J.P.; Leiner, T.; Planken, R.N.; Išgum, I. Automatic coronary artery plaque quantification and CAD-RADS prediction using mesh priors. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 43, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Qiu, X.; Chu, Y.; Wang, K.; Qiu, Z.; Luo, G.; Gao, X. A Causal-Holistic Adaptive Intervention Network for Tailoring Automated Coronary Artery Disease Diagnosis to Individual Patients. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2025, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 23–27 September 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tejero-de Pablos, A.; Huang, K.; Yamane, H.; Kurose, Y.; Mukuta, Y.; Iho, J.; Tokunaga, Y.; Horie, M.; Nishizawa, K.; Hayashi, Y.; et al. Texture-based classification of significant stenosis in CCTA multi-view images of coronary arteries. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2019, Shenzhen, China, 13–17 October 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 732–740. [Google Scholar]

- Denzinger, F.; Wels, M.; Ravikumar, N.; Breininger, K.; Reidelshöfer, A.; Eckert, J.; Sühling, M.; Schmermund, A.; Maier, A. Coronary artery plaque characterization from CCTA scans using deep learning and radiomics. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2019, Shenzhen, China, 13–17 October 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Penso, M.; Moccia, S.; Caiani, E.G.; Caredda, G.; Lampus, M.L.; Carerj, M.L.; Babbaro, M.; Pepi, M.; Chiesa, M.; Pontone, G. A token-mixer architecture for CAD-RADS classification of coronary stenosis on multiplanar reconstruction CT images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 153, 106484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, A.; Zheng, J.; Gong, T.; Sun, Q.; Weir-McCall, J.; O’Regan, D.P.; Williams, M.C.; Newby, D.E.; Rudd, J.H.; Huang, Y. ViTAL-CT: Vision Transformers for High-Risk Plaque Classification in Coronary CTA. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2025, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 23–27 September 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 681–690. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.; Chai, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, R.; Wei, Q.; Huang, M.; Huang, W. Improved Cascade-RCNN for automatic detection of coronary artery plaque in multi-angle fusion CPR images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 99, 106880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Luosang, G.; Peng, G.; Peng, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yi, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Coronary Artery Calcification Segmentation by Using Cross-Frequency Conditioner and Geometric Priors Learning. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2025, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 23–27 September 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, J. Coronary r-cnn: Vessel-wise method for coronary artery lesion detection and analysis in coronary ct angiography. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2022, Singapore, 18–22 September 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Peng, J.; Zhang, K.; Fan, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y. TMN-Net: A Hybrid 2.5 D Multi-Branch Transformer Network for Coronary Artery Segmentation in Cardiac Diagnosis. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 115581–115603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Luo, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, K. Transformer network for significant stenosis detection in CCTA of coronary arteries. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2021, Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 516–525. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Language Modeling, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 11 April–10 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Li, F.; Wang, B. U-mamba: Enhancing long-range dependency for biomedical image segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04722. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.; Ye, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. Segmamba: Long-range sequential modeling mamba for 3d medical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2024, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 578–588. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y.; Li, Z. Medmamba: Vision mamba for medical image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H. Mambamil: Enhancing long sequence modeling with sequence reordering in computational pathology. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2024, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.02491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Cho, S.; Kwak, S. Weakly supervised learning of instance segmentation with inter-pixel relations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2209–2218. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Weakly-supervised semantic segmentation network with deep seeded region growing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7014–7023. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.Y.; Williamson, D.F.; Chen, T.Y.; Chen, R.J.; Barbieri, M.; Mahmood, F. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Bian, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y. Transmil: Transformer based correlated multiple instance learning for whole slide image classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 2136–2147. [Google Scholar]

- Valvano, G.; Leo, A.; Tsaftaris, S.A. Learning to segment from scribbles using multi-scale adversarial attention gates. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 40, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, L. Topology-preserving automatic labeling of coronary arteries via anatomy-aware connection classifier. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 October 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zou, M.; Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, K.; Qiu, Z.; Gao, X.; Li, S. Spatio-Temporal Contrast Network for Data-Efficient Learning of Coronary Artery Disease in Coronary CT Angiography. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2024, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 645–655. [Google Scholar]

| Methods | Acc | Prec | Sens | Spec | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tejero-de Pablos et al. [16] | 82.1 ± 1.9 | 81.3 ± 2.4 | 80.4 ± 2.1 | 85.2 ± 1.5 | 80.7 ± 2.0 |

| Denzinger et al. [17] | 83.7 ± 1.4 | 82.5 ± 1.6 | 82.1 ± 1.8 | 86.4 ± 1.2 | 82.3 ± 1.5 |

| Zreik et al. [10] | 85.3 ± 1.2 | 84.4 ± 1.4 | 83.6 ± 1.3 | 88.1 ± 1.0 | 83.9 ± 1.3 |

| Zhang et al. [22] | 86.9 ± 1.1 | 85.7 ± 1.0 | 85.4 ± 1.1 | 89.6 ± 0.9 | 85.5 ± 1.1 |

| Van Herten et al. [14] | 87.6 ± 0.8 | 86.4 ± 0.9 | 86.1 ± 1.0 | 90.3 ± 0.7 | 86.2 ± 0.8 |

| Ma et al. [38] | 88.1 ± 0.9 | 87.3 ± 0.8 | 87.4 ± 0.9 | 91.1 ± 0.6 | 87.1 ± 0.8 |

| Le et al. [19] | 89.3 ± 0.7 | 88.6 ± 0.7 | 88.7 ± 0.8 | 92.1 ± 0.5 | 88.5 ± 0.7 |

| Zhang et al. [12] | |||||

| MG-HGLNet (Ours) | 92.4 ± 0.5 | 91.7 ± 0.6 | 92.1 ± 0.6 | 95.3 ± 0.4 | 91.8 ± 0.5 |

| Methods | Acc | Prec | Sens | Spec | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zreik et al. [10] | 80.4 ± 1.7 | 79.1 ± 1.9 | 78.6 ± 2.0 | 84.3 ± 1.4 | 78.7 ± 1.8 |

| Zhang et al. [22] | 84.5 ± 1.3 | 83.2 ± 1.5 | 82.9 ± 1.4 | 87.6 ± 1.1 | 83.0 ± 1.3 |

| Van Herten et al. [14] | 86.3 ± 0.9 | 85.4 ± 1.0 | 85.1 ± 1.1 | 89.4 ± 0.8 | 85.2 ± 0.9 |

| Ma et al. [38] | |||||

| MG-HGLNet (Ours) | 91.5 ± 0.6 | 90.9 ± 0.7 | 90.3 ± 0.7 | 94.2 ± 0.5 | 90.6 ± 0.6 |

| Modules | Stenosis Grading Task | Plaque Classification Task | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDE | SSD | MSO | Acc | Prec | Sens | Spec | F1 | Acc | Prec | Sens | Spec | F1 |

| − | − | − | 86.5 | 85.8 | 85.3 | 88.0 | 85.6 | 85.2 | 84.5 | 83.1 | 87.8 | 83.8 |

| ✓ | − | − | 89.1 | 88.4 | 88.9 | 90.5 | 88.6 | 86.8 | 86.1 | 85.4 | 89.1 | 85.7 |

| ✓ | ✓ | − | 90.8 | 90.2 | 90.5 | 93.1 | 90.4 | 89.8 | 89.0 | 88.7 | 92.4 | 88.5 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 92.4 | 91.7 | 92.1 | 95.3 | 91.8 | 91.5 | 90.9 | 90.3 | 94.2 | 90.6 |

| Class | Prec | Sens | Spec | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 96.2 | 97.8 | 97.9 | 97.0 |

| Mild | 89.1 | 87.5 | 93.8 | 88.3 |

| Moderate | 87.5 | 88.5 | 93.0 | 88.0 |

| Severe | 94.0 | 94.6 | 96.5 | 94.3 |

| Macro-Avg | 91.7 | 92.1 | 95.3 | 91.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Q. MG-HGLNet: A Mixed-Grained Hierarchical Geometric-Semantic Learning Framework with Dynamic Prototypes for Coronary Artery Lesions Assessment. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010118

Wang X, Chen Y, Wu Y, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Feng Q. MG-HGLNet: A Mixed-Grained Hierarchical Geometric-Semantic Learning Framework with Dynamic Prototypes for Coronary Artery Lesions Assessment. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiangxin, Yangfan Chen, Yi Wu, Yujia Zhou, Yang Chen, and Qianjin Feng. 2026. "MG-HGLNet: A Mixed-Grained Hierarchical Geometric-Semantic Learning Framework with Dynamic Prototypes for Coronary Artery Lesions Assessment" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010118

APA StyleWang, X., Chen, Y., Wu, Y., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., & Feng, Q. (2026). MG-HGLNet: A Mixed-Grained Hierarchical Geometric-Semantic Learning Framework with Dynamic Prototypes for Coronary Artery Lesions Assessment. Bioengineering, 13(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010118