Transfer Learning Approach with Features Block Selection via Genetic Algorithm for High-Imbalance and Multi-Label Classification of HPA Confocal Microscopy Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

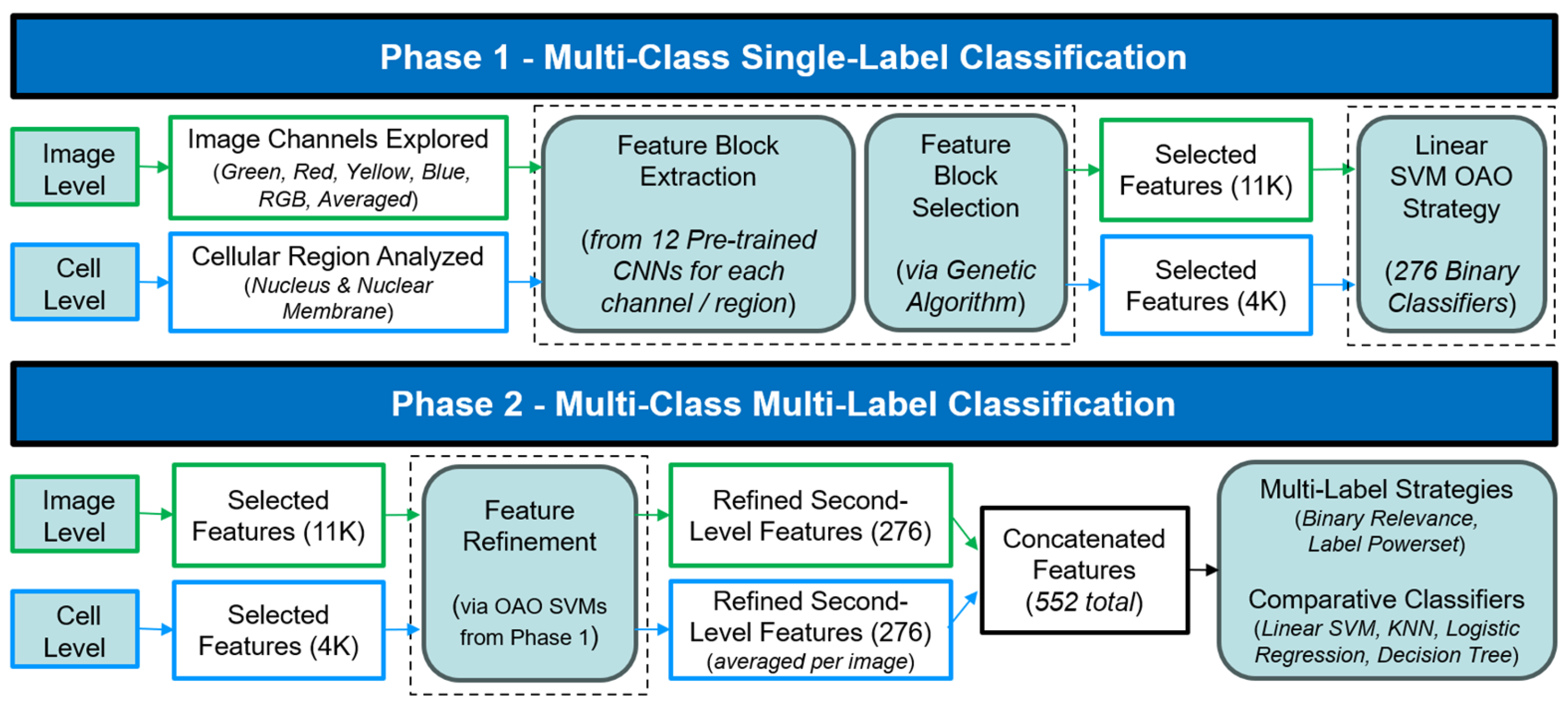

- A dual-level classification framework integrating both image-level and cell-level analysis, introducing two regions of interest at the cellular level (nucleus and nuclear membrane), whose joint use has not been previously investigated in the HPA literature.

- Feature-based transfer learning across twelve pre-trained CNN architectures, one of the most comprehensive evaluations applied to the HPA dataset.

- GA for selecting sub-optimal combinations of CNN feature blocks, addressing the high-dimensional combinatorial search space (272 combinations).

- Investigation of discriminative channel combinations in multi-channel fluorescence microscopy.

- Two-phase, computationally efficient strategy for multi-class and multi-label tasks, avoiding costly fine-tuning while achieving strong performance, especially for rare classes.

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

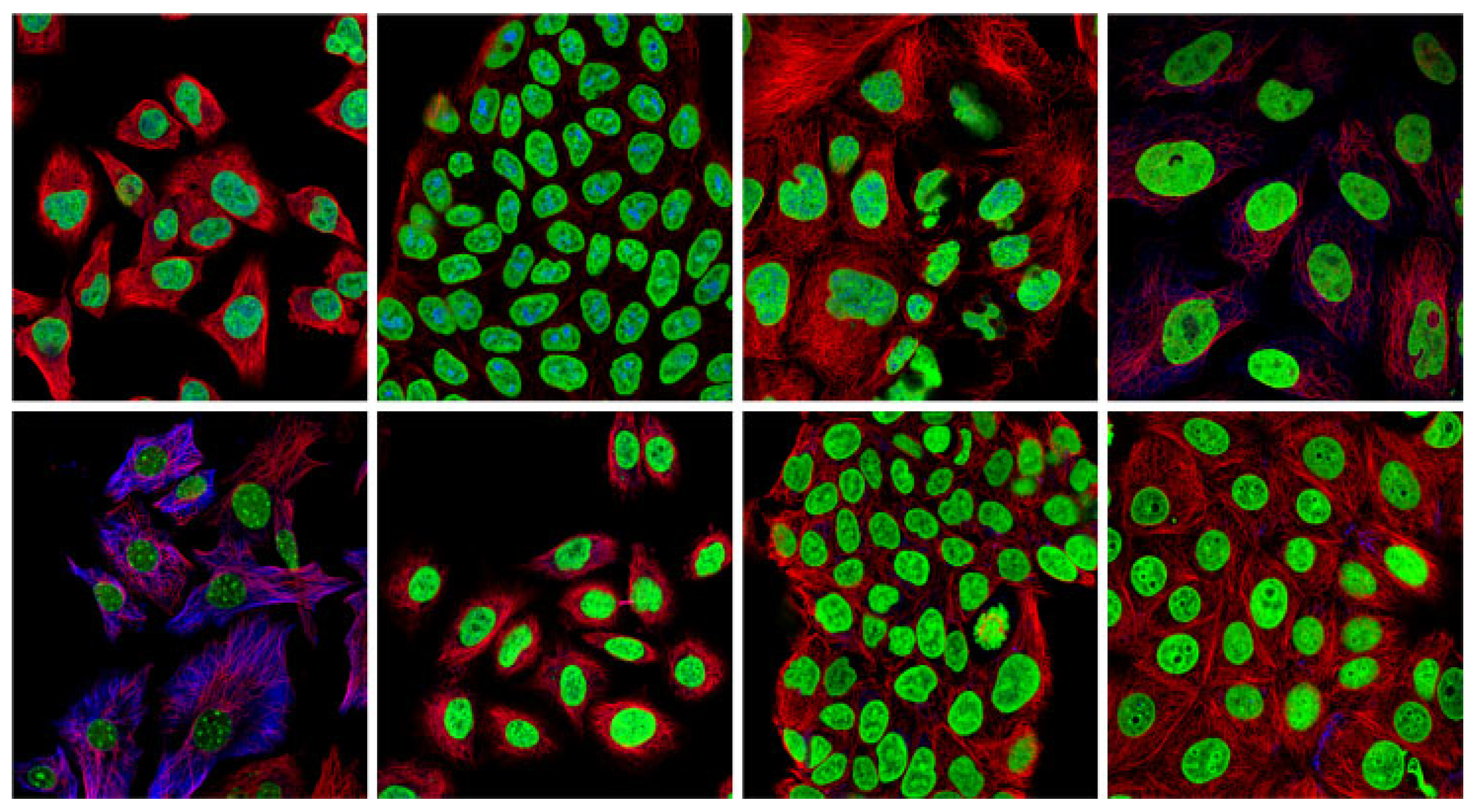

3.1. Human Protein Atlas Dataset

3.2. Pre-Trained CNN

3.3. Proposed Two-Phase Sustainable Method and Data Splitting

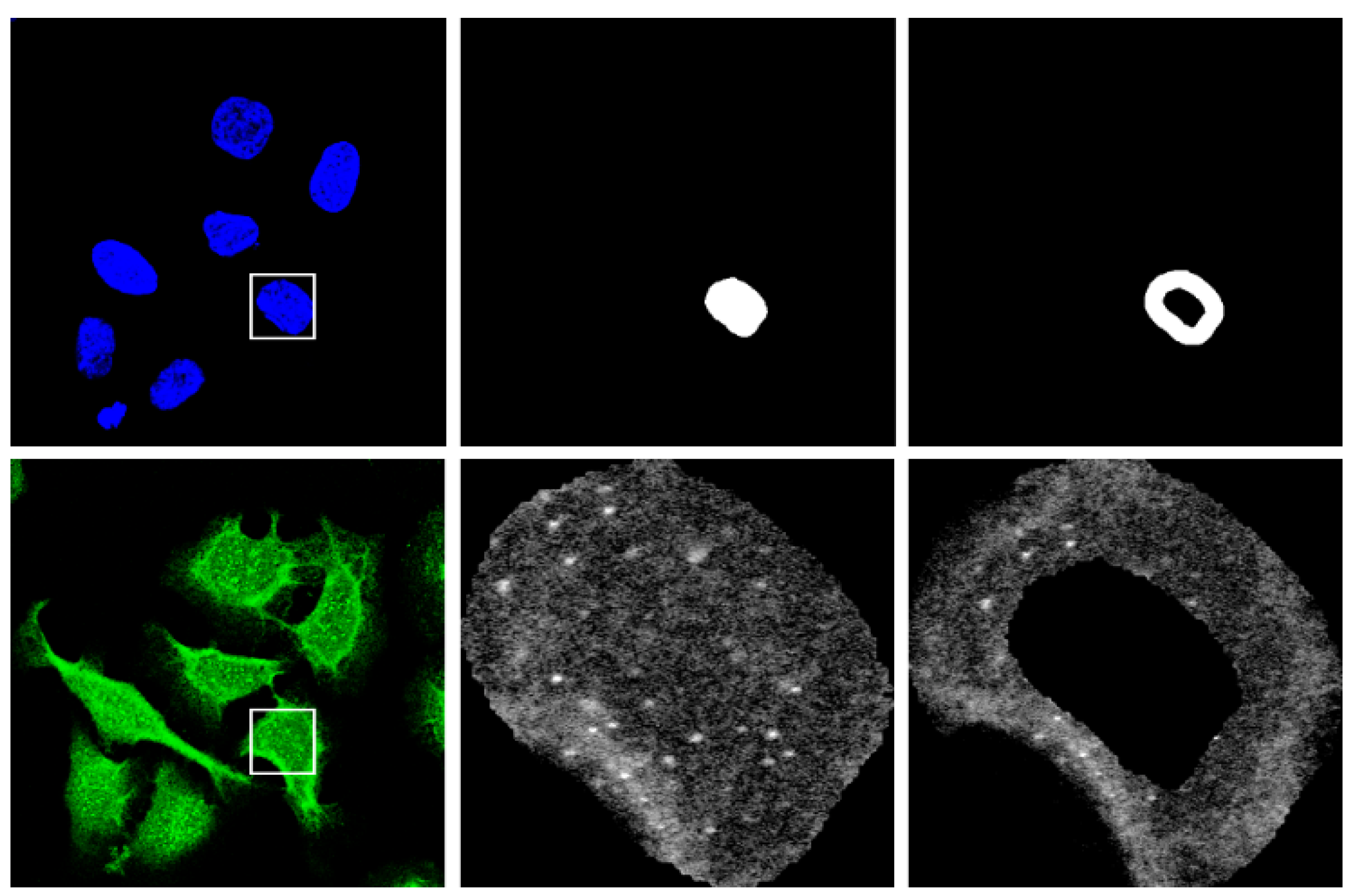

3.4. Image Preprocessing and Segmentation

3.5. Features Block Extraction and Selection with Genetic Algorithm

3.6. Classification Strategies: Multi-Class and Multi-Label Approaches

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Multi-Class Single-Label Results

4.2. Multi-Class Multi-Label Results

5. Conclusions

Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Pattern Name | Pattern Name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Nucleoplasm | 14 | Microtubules |

| 1 | Nuclear Membrane | 15 | Microtubule Ends |

| 2 | Nucleoli | 16 | Cytokinetic Bridge |

| 3 | Nucleoli Fibrillar Center | 17 | Mitotic Spindle |

| 4 | Nuclear Speckles | 18 | Microtubule Organ. Centre |

| 5 | Nuclear Bodies | 19 | Centrosome |

| 6 | Endoplasmic Reticulum | 20 | Lipid Droplets |

| 7 | Golgi Apparatus | 21 | Cell Junctions |

| 8 | Peroxisomes | 22 | Plasma Membrane |

| 9 | Endosomes | 23 | Mitochondria |

| 10 | Lysosomes | 24 | Aggresome |

| 11 | Intermediate Filaments | 25 | Cytosol |

| 12 | Actin Filaments | 26 | Cytoplasmic Bodies |

| 13 | Focal Adhesion Sites | 27 | Rods & Rings |

| Pre-Trained CNNs | Layers | Layer for Feat. Extraction | Mean Time for One Image (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlexNet | 25 | Fc8 | 0.027 |

| VGG-16 | 41 | Fc8 | 0.304 |

| VGG-19 | 47 | Fc8 | 0.348 |

| MobileNet-v2 | 53 | Logits | 0.055 |

| SqueezeNet | 68 | Pool10 | 0.042 |

| ResNet-18 | 68 | Fc1000 | 0.065 |

| GoogleNet | 144 | Loss3-classifier | 0.114 |

| ResNet-50 | 177 | Fc1000 | 0.095 |

| Inception-v3 | 315 | Predictions | 0.188 |

| ResNet-101 | 347 | Fc1000 | 0.172 |

| DenseNet-201 | 708 | Fc1000 | 0.255 |

| InceptionResNet-v2 | 824 | Predictions | 0.367 |

| Pattern Name | F1 | Precision | Recal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleoplasm | 0 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.86 |

| Nuclear Membr. | 1 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.75 |

| Nucleoli | 2 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.62 |

| Nucleoli Fibr. Cen. | 3 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.58 |

| Nuclear Speckles | 4 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.70 |

| Nuclear Bodies | 5 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.52 |

| Endoplasmic Ret. | 6 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.50 |

| Golgi Apparatus | 7 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.55 |

| Peroxisomes | 8 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.64 |

| Endosomes | 9 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Lysosomes | 10 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.83 |

| Intermediate Fil. | 11 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.59 |

| Actin Filaments | 12 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.48 |

| Focal Adhes. Sites | 13 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.43 |

| Microtubules | 14 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| Microtubule Ends | 15 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Cytokinetic Bridge | 16 | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.21 |

| Mitotic Spindle | 17 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.42 |

| Microt.Org. Cen. | 18 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.39 |

| Centrosome | 19 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.30 |

| Lipid Droplets | 20 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.53 |

| Cell Junctions | 21 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| Plasma Membrane | 22 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.40 |

| Mitochondria | 23 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.69 |

| Aggresome | 24 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.34 |

| Cytosol | 25 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.68 |

| Cytoplasmic Bod. | 26 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.36 |

| Rods & Rings | 27 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 1.00 |

| Macro AVG | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.56 | |

| Weighted AVG | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.66 |

References

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Winsnes, C.; Hjelmare, M.; Cesnik, A.; Åkesson, L.; Xu, H.; Sullivan, D.; Dai, S.; Lan, J.; Jinmo, P.; et al. Analysis of the Human Protein Atlas Image Classification competition. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Protein Atlas Image Classification. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/human-protein-atlas-image-classification (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.-J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Human Protein Classification in Microscope Images Using Deep Learning and Focal-Lovász Loss. In Proceedings of the ICVIP 2020: 2020 The 4th International Conference on Video and Image, Xi’an, China, 25–27 December 2020; Volume PartF168342, pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Joudi, L.; Arif, M. Classification of Human Protein in Multiple Cells Microscopy Images Using CNN, Computers. Mater. Contin. 2023, 76, 1763–1780. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, D.; Winsnes, C.; Akesson, L.; Hjelmare, M.; Wiking, M.; Schutten, R.; Campbell, L.; Leifsson, H.; Rhodes, S.; Nordgren, A.; et al. Deep learning is combined with massive-scale citizen science to improve large-scale image classification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wan, B.; Zhu, S.; Yang, F. MMLoc: A Multi-instance Multilabel Learning Approach for Predicting Protein Subcellular Localization from Immunofluorescence Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), Guangzhou, China, 19–21 January 2024; pp. 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Liimatainen, K.; Huttunen, R.; Latonen, L.; Ruusuvuori, P. Convolutional neural network-based artificial intelligence for classification of protein localization patterns. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwetha, T.R.; Thomas, S.A.; Kamath, V.; Niranjana, K.B. Hybrid xception model for human protein atlas image classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th India Council International Conference (INDICON), Rajkot, India, 13–15 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Lei, H.; Shen, H.-B.; Yang, Y. SIFLoc: A self-supervised pretraining method for enhancing the recognition of protein subcellular localization in immunofluorescence microscopic images. Briengs Bioinform. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, D.; Gulzar, Y.; Juneja, S.; Alwan, A.; Nauman, A. An Artificial Intelligence-Based Stacked Ensemble Approach for Prediction of Protein Subcellular Localization in Confocal Microscopy Images. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.; Sowmya, A.; Meijering, E.; Song, Y. Imbalanced classification for protein subcellular localization with multilabel oversampling. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, V.; Tegolo, D.; Valenti, C. Transfer Learning Approach for High-Imbalance and Multi-class Classification of Fluorescence Images. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2025, 15350, 461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Taormina, V.; Cascio, D.; Abbene, L.; Raso, G. Performance of fine-tuning convolutional neural networks for HEP-2 image classification. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Rachmad, Y. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 2, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.4842. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for largescale image recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1512.00567. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.04381. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-Level Accuracy with 50x Fewer Parameters and <0.5MB Model Size. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.07360 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K. Densely connected convolutional networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1608.06993. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1602.07261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sechidis, K.; Tsoumakas, G.; Vlahavas, I. On the stratification of multi label data. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2011, 6913, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, C.; Wang, T.; Michaelos, M.; Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: A generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TheMathWorks Inc. MATLAB R2024a; TheMathWorks Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.mathworks.com (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Simon, D. (Ed.) Evolutionary Optimization Algorithms; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, C. A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1998, 2, 121–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürnkranz, J. Round Robin Classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2002, 2, 721–747. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, R.; Takahide, N.; Takahashi, H. A decision based one-against-one method for multi-class support vector machine. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2004, 7, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoumakas, G.; Katakis, I. Multi-label classification: An overview. Int. J. Data Warehous. Min. 2007, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Hu, Y.; Tian, Z.; Shen, K. Logistic Regression Model Optimization and Case Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology (ICCSNT), Dalian, China, 19–20 October 2019; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J. Learning decision tree classifiers. ACM Comput. Surv. 1996, 28, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, J.; Pihl, P. Inspecting Product Quality with Computer Vision Techniques: Comparing Traditional Image Processing Methods with Deep Learning Methodson Small Datasets in Finding Surface Defects. 2021. Available online: http://hj.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1579764&dswid=3906 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Bisong, E.; Bisong, E. Google colaboratory. Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Vivona, L.; Cascio, D.; Bruno, S.; Fauci, A.; Taormina, V.; Elgaaied, A.; Gorgi, Y.; Triki, R.; Ahmed, M.B.; Yalaoui, S.; et al. AI-Driven Blind Signature Classification for IoT Connectivity: A Deep Learning Approach; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, I.; Bhadauria, H.S.; Virmani, J.; Thakur, S. A hybrid hierarchical framework for classification of breast density using digitized film screen mammograms. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 18789–18813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Core Methodology and Focus | Scope of Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Ouyang et al. [2] | Optimized DenseNet architecture; ensemble of whole-image and cell-segmented pipelines; Multi-Label Stratification; extensive data augmentation. | Full dataset (28 classes), multi-label classification. |

| Wang et al. [5] | Ensemble of pre-trained CNNs (ResNet-50, DenseNet-121, SE-ResNeXt-50); composite Focal-Lovász loss for minority classes; 4-channel input. | Full dataset (28 classes), multi-label. |

| Al-Joudi et al. [6] | CNN-based approach (GapNet-PL), utilizing oversampling/undersampling for imbalance. Image-level analysis (4 channels). | Full dataset (28 classes), multi-label. |

| Sullivan et al. [7] | Loc-CAT deep model combined with large-scale citizen-science annotations; transfer learning from game-generated labels. | 29 localization patterns; 33 M human annotations. |

| Zhang et al. [8] | Multi-Instance Multi-Label Learning (MIML). Features extracted from segmented cell patches (U-Net). Transfer Learning (ResNet-50, DenseNet-121). | Subset of 8 patterns; 5772 images. |

| Liimatainen et al. [9] | Custom CNN and FCN architectures (10 convolutional layers); 4-channel input; straightforward architecture design. | Subset of 13 classes; 20,000 images. |

| Tr et al. [10] | Hybrid Xception CNN compared against Conventional Handcrafted Features (Haralick, LBP, Zernike). Image-level analysis. | Subset of 15 classes; 14,094 samples. |

| Tu et al. [11] | Two-stage method: Self-Supervised Pre-training followed by Supervised Learning. MIML-like approach using patches. Used RGB Images. | 19,777 Images (173,594 patches). |

| Aggarwal et al. [12] | Focuses on Transfer Learning (VGG16, ResNet152, DenseNet169) and a Stacked Ensemble. Uses 3 channels (Red, Blue, Green composite). | Full dataset (28 classes), multi-label. |

| Rana et al. [13] | Oversampling via non-linear mix-up and transformations to generate synthetic samples for imbalance. Image-level analysis. Uses 3 Channels (Red, Green, Yellow). | Full dataset (28 classes), multi-label. |

| Pre-Trained CNNs | Layers | Pre-Trained CNNs | Layers |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlexNet [16] | 25 | GoogleNet [17] | 144 |

| VGG-16 [18] | 41 | ResNet-50 [19] | 177 |

| VGG-19 [18] | 47 | Inception-v3 [20] | 315 |

| MobileNet-v2 [21] | 53 | ResNet-101 [19] | 347 |

| SqueezeNet [22] | 68 | DenseNet-201 [23] | 708 |

| ResNet-18 [19] | 68 | InceptionResNet-v2 [24] | 824 |

| Pre-Trained CNNs | Layers |

|---|---|

| MobileNet-v2, ResNet-18, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, DenseNet-201, GoogleNet, VGG-16, VGG-19 | 224 × 224 × 3 |

| AlexNet, SqueezeNet | 227 × 227 × 3 |

| Inception-v3, InceptionResNet-v2 | 299 × 299 × 3 |

| Pre-Trained CNNs | Layer Used |

|---|---|

| GoogleNet | Loss3-classifier |

| MobileNet-v2 | Logits |

| ResNet-18, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, DenseNet-201 | Fc1000 |

| AlexNet, VGG-16, VGG-19 | Fc8 |

| SqueezeNet | Pool10 |

| Inception-v3, InceptionResNet-v2 | Predictions |

| Features Concatenation | F1 Macro (OAO) | F1 Macro (OAA) |

|---|---|---|

| Best layer | 0.2736 | 0.2664 |

| Best two layers | 0.3014 | 0.2837 |

| Best three layers | 0.3085 | 0.2879 |

| Best four layers | 0.3116 | 0.3085 |

| Best five layers | 0.3201 | 0.3083 |

| Best six layers | 0.3179 | 0.3027 |

| All twelve layers | 0.3155 | 0.2940 |

| Configuration | F1 Macro |

|---|---|

| Best layer green channel | 0.2736 |

| Best five-layer green channel | 0.3201 |

| All twelve-layer green channels | 0.3155 |

| Best individual from AG (green channel) | 0.3220 |

| Best individual from AG | 0.3681 |

| Configuration | F1 Macro |

|---|---|

| Best layer nuclear region | 0.1699 |

| Best layer nuclear membrane region | 0.1301 |

| Best layers concatenation from two region | 0.1865 |

| Best individual from GA | 0.1920 |

| F1 (Macro) | Precision (Macro) | Recall (Macro) | F1 (Weighted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Level | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.48 |

| Cellular Level | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.34 |

| Image Level (F1 Macro) | Cell Level (F1 Macro) | Image & Cell (F1 Macro) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BR (logistic) | 0.3288 | 0.2624 | 0.4116 |

| BR (decision tree) | 0.3179 | 0.2831 | 0.3388 |

| BR (Knn k = 1) | 0.4394 | 0.3454 | 0.4608 |

| BR (Knn k = 3) | 0.3333 | 0.2831 | 0.3719 |

| BR (SVM) | 0.4553 | 0.3566 | 0.5269 |

| LP (logistic) | 0.4533 | 0.2994 | 0.3037 |

| LP (decision tree) | 0.2348 | 0.2188 | 0.2557 |

| LP (Knn k = 1) | 0.4553 | 0.3416 | 0.5269 |

| LP (knn k = 3) | 0.4081 | 0.3319 | 0.4405 |

| LP (SVM) | 0.5008 | 0.4231 | 0.5909 |

| F1 (Macro) | Precision (Macro) | Recall (Macro) | F1 (Weighted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Level | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.59 |

| Cellular Level | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.60 |

| Concatenation Image & Cell | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.68 |

| F1 (Macro) | Precision (Macro) | Recall (Macro) | F1 (Weighted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human level [2] | 0.71 | - | - | - |

| Winner Kaggle competition [2] | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.55 | - |

| Wang et al. [5] | 0.53 | - | - | - |

| Rana et al. [13] | 0.48 | - | - | - |

| Tu et al. [11] | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.72 |

| Sullivan et al. [7] | 0.47 | - | - | - |

| Al-Joudi et al. [6] | - | - | - | 0.54 |

| Aggarwal et al. [12] | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.71 |

| Our approach | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taormina, V.; Tegolo, D.; Valenti, C. Transfer Learning Approach with Features Block Selection via Genetic Algorithm for High-Imbalance and Multi-Label Classification of HPA Confocal Microscopy Images. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121379

Taormina V, Tegolo D, Valenti C. Transfer Learning Approach with Features Block Selection via Genetic Algorithm for High-Imbalance and Multi-Label Classification of HPA Confocal Microscopy Images. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(12):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121379

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaormina, Vincenzo, Domenico Tegolo, and Cesare Valenti. 2025. "Transfer Learning Approach with Features Block Selection via Genetic Algorithm for High-Imbalance and Multi-Label Classification of HPA Confocal Microscopy Images" Bioengineering 12, no. 12: 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121379

APA StyleTaormina, V., Tegolo, D., & Valenti, C. (2025). Transfer Learning Approach with Features Block Selection via Genetic Algorithm for High-Imbalance and Multi-Label Classification of HPA Confocal Microscopy Images. Bioengineering, 12(12), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121379