Unsaturation-Driven Modulation of Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activities of Cardanol Derivatives

Abstract

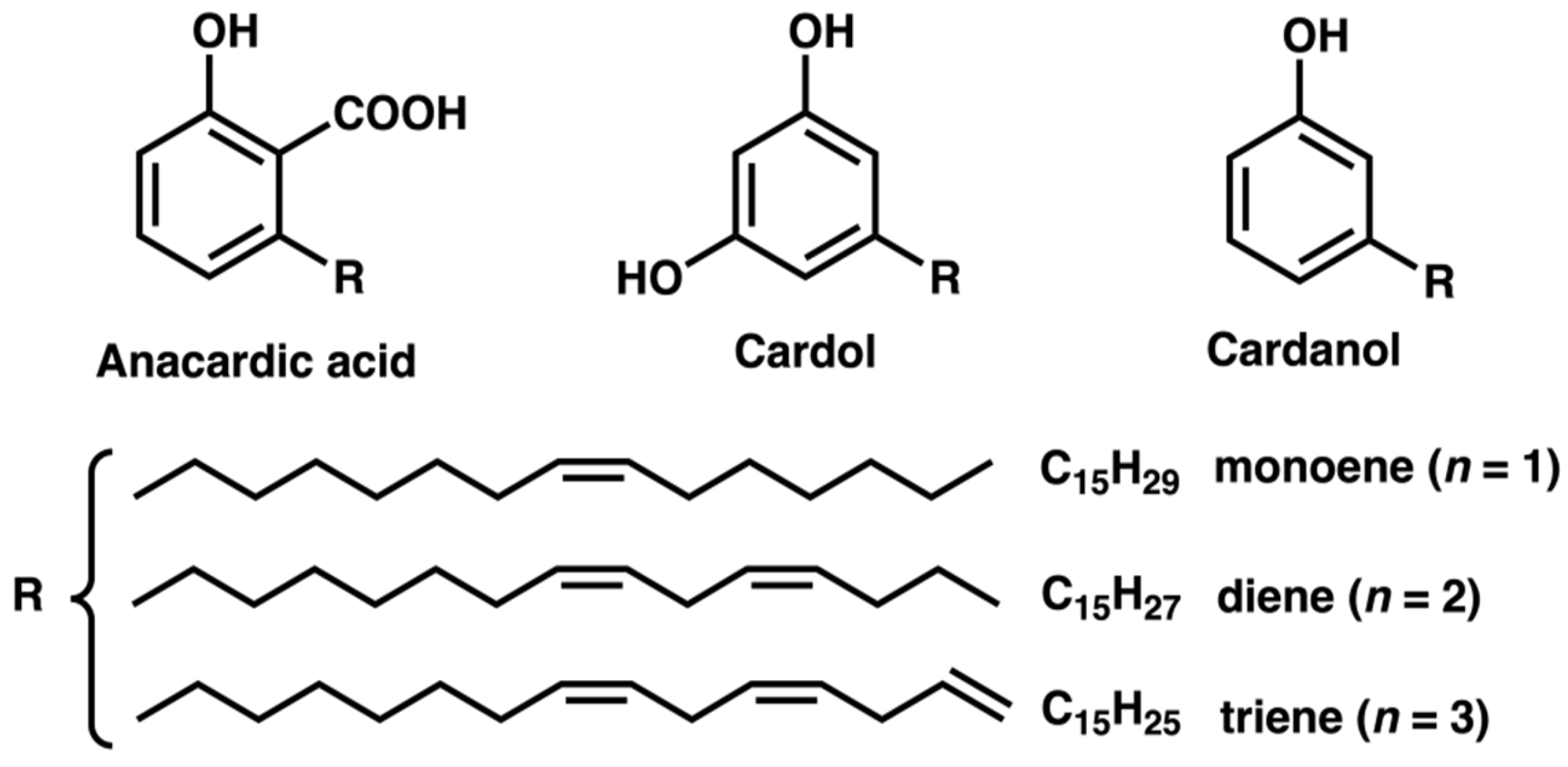

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Solvents and Reagents

2.2. Extraction and Separation of Cardanol Compounds from Technical Cashew Nutshell Liquid

2.3. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

2.4. Spectroscopic Analysis

2.5. Determination of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Assessment of Anticholinesterase Activity

2.7. Brine Shrimp Lethality Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Docking Molecular and Molecular Dynamics

3. Results and Discussion

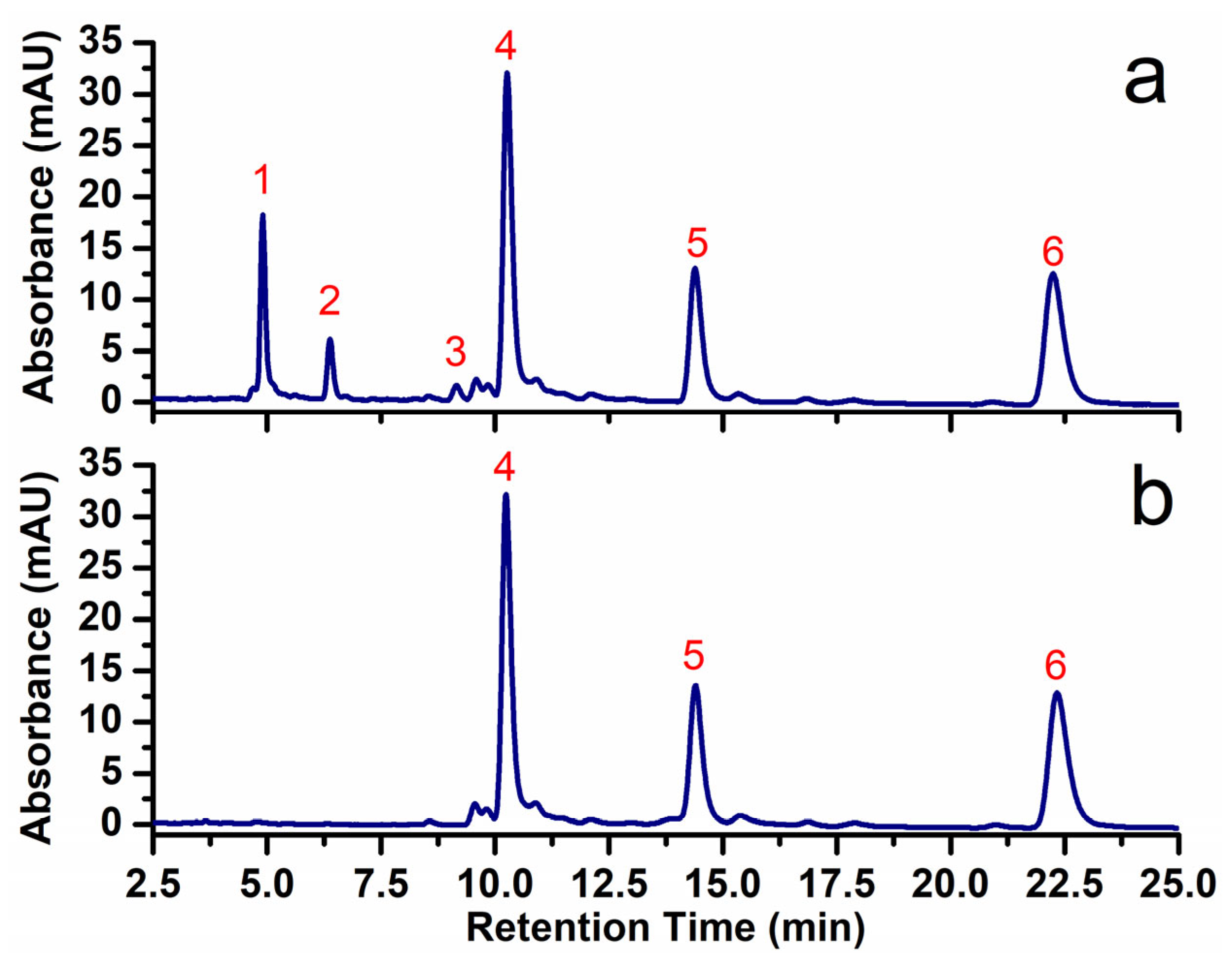

3.1. Chromatographic Analysis

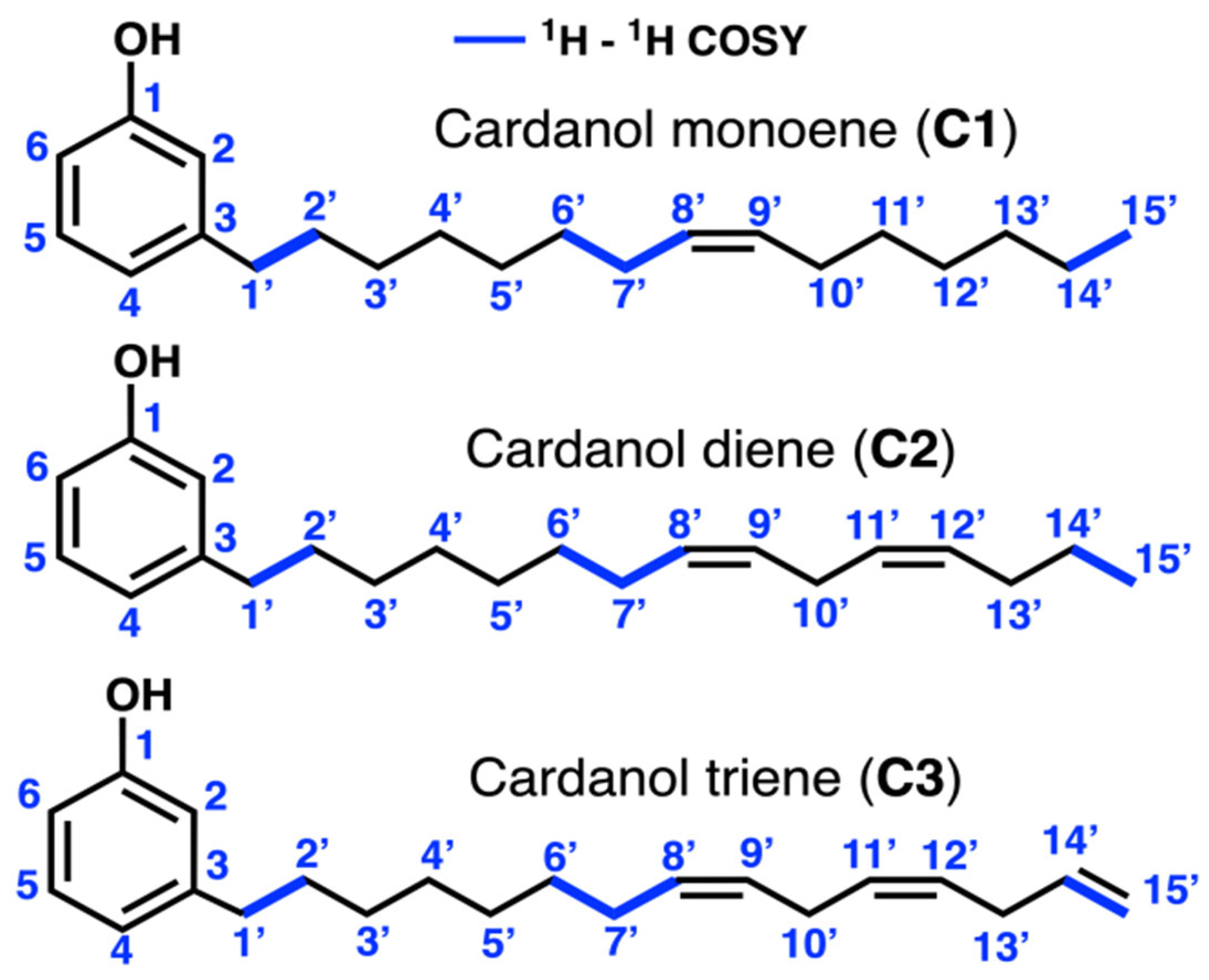

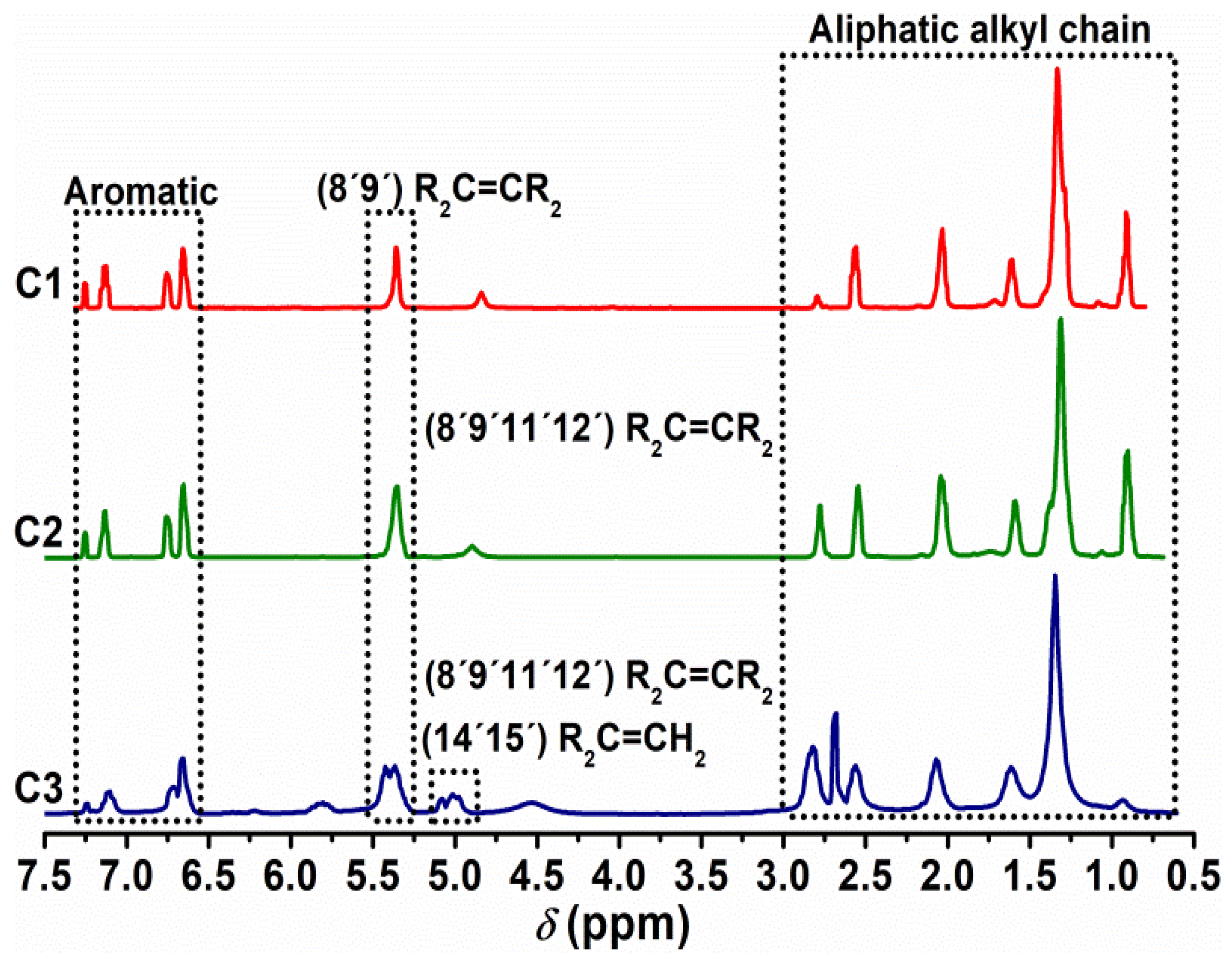

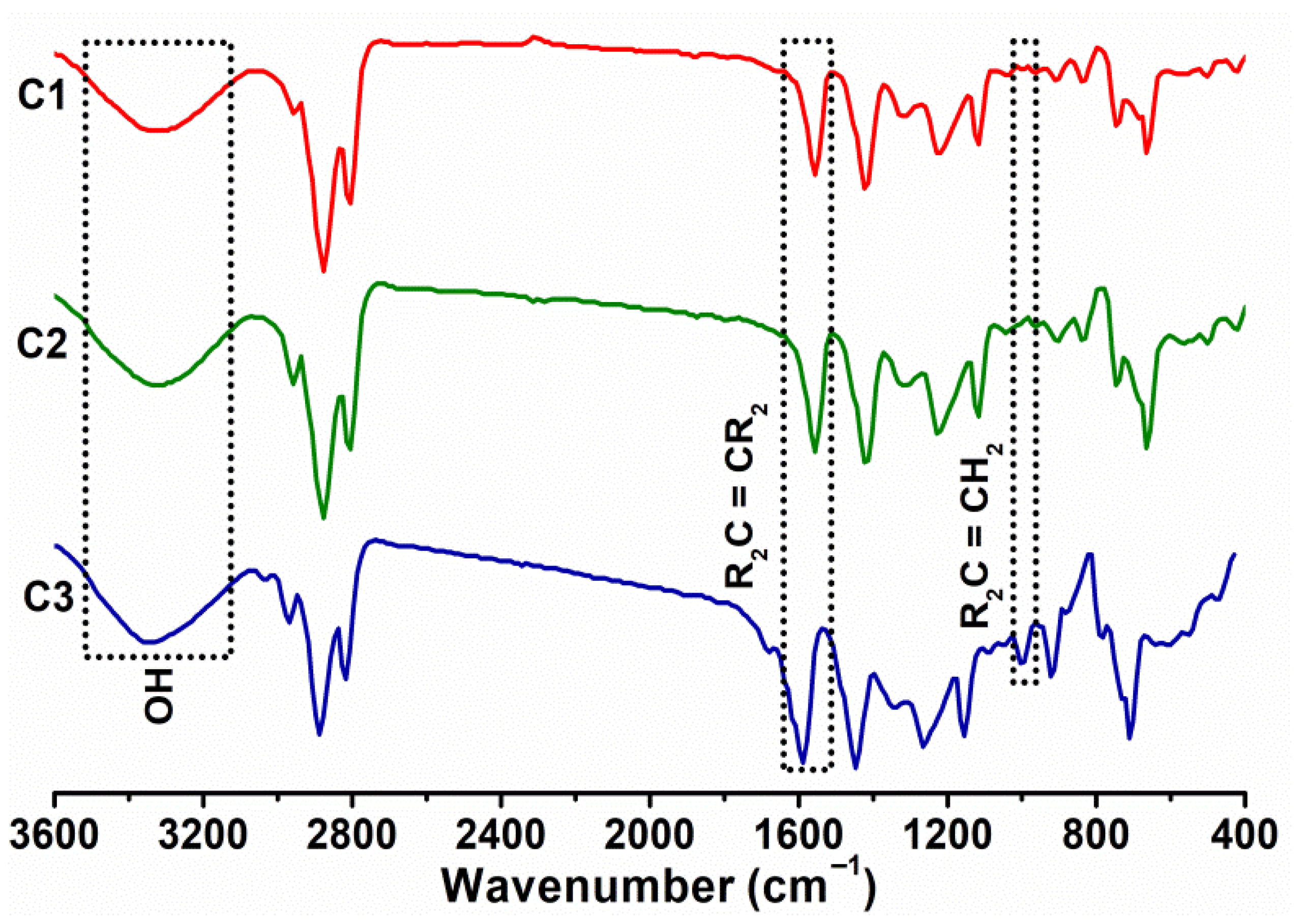

3.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Infrared Spectroscopy

3.3. Biological Activity of Cardanols from CNSL

| Compound | DPPH IC50 (µg/mL, 95% CI) | DPPH IC50 (µM, 95% CI) | BSLT LC50 (µg/mL, 95% CI) | AChE Inhibition Zone (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 1000.00 ± 200.00 a [773.68–1226.32] | 3311.26 ± 662.25 [2561.88–4060.12] | 43,186.00 ± 1991.00 a [40,932.97–45,439.03] | 0.6 |

| C2 | 340.00 ± 20.00 b [317.37–362.63] | 1133.33 ± 67.00 [1057.18–1208.82] | 41,973.00 ± 1991.00 a [39,719.97–44,226.03] | 0.6 |

| C3 | 179.00 ± 5.00 c [173.34–184.66] | 600.00 ± 17.00 [580.76–619.24] | 4118.00 ± 328.00 b [3746.83–4489.17] | 0.8 |

| Cardanol | 551.00 ± 20.00 b [528.37–573.63] | - | 4270.00 ± 145.00 b [4105.92–4434.08] | 0.9 |

| Quercetin | 4.77 ± 0.50 | - | - |

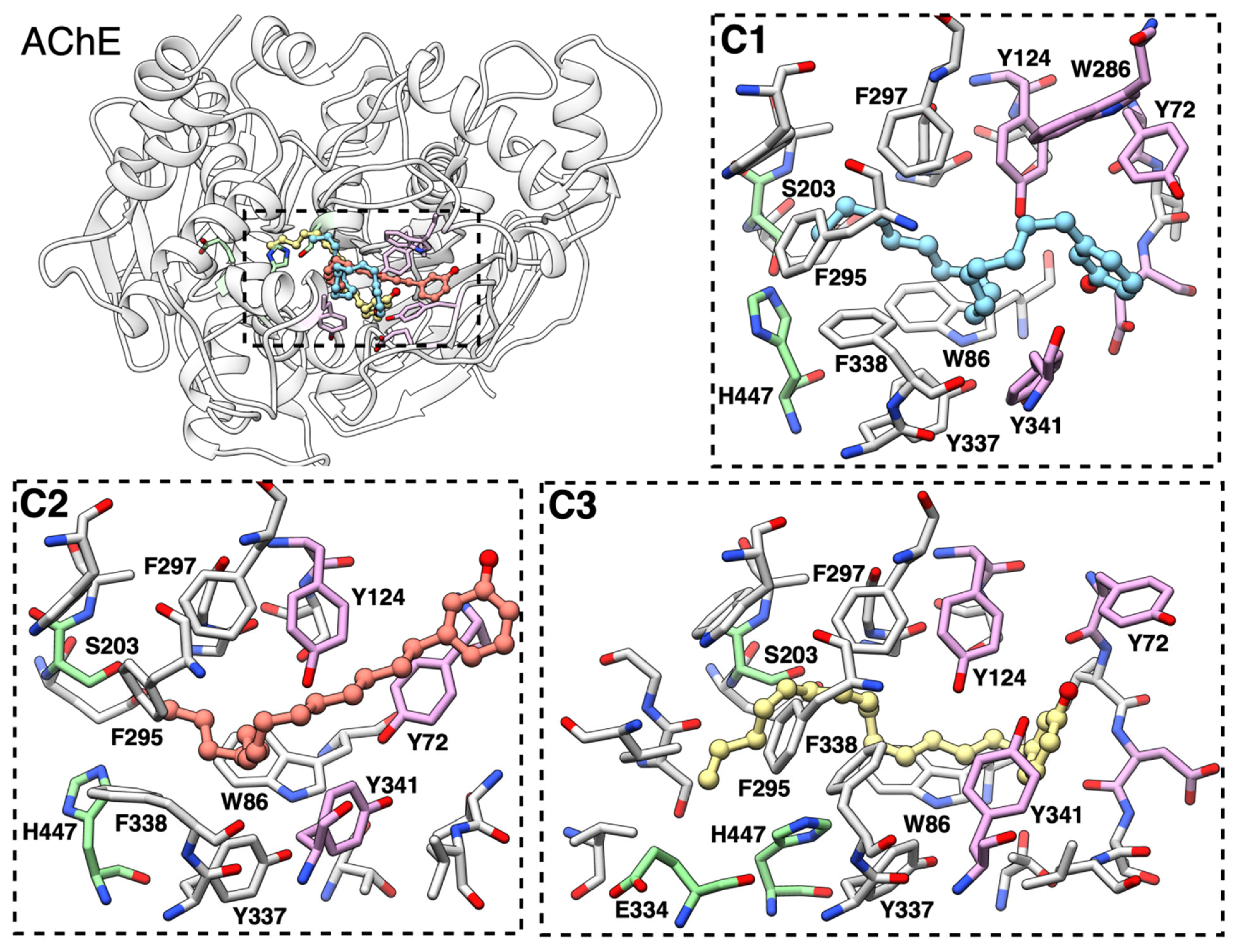

3.4. Docking Molecular and Molecular Dynamics Simulations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIONE | Companhia Industrial de Óleos do Nordeste |

| BSLT | Brine Shrimp Lethality Test |

| CNSL | Cashew nutshell liquid |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DTNB | 5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) |

| ACTI | Acetylthiocholine iodide |

| CAS | Catalytic Active Site |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PAS | Peripheral Catalytic Site |

| TLC | Thin-layer Chromatography |

| ESP | Electrostatic Potential |

| NPT | Isothermal-isobaric Ensemble |

| NVT | ns at constant volume |

| NPs | nanoparticles |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

References

- Pell, S.K. Molecular Systematics of the Cashew Family (Anacardiaceae); Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bloise, E.; Lazzoi, M.R.; Mergola, L.; Del Sole, R.; Mele, G. Advances in Nanomaterials Based on Cashew Nut Shell Liquid. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnath, N.; Appavoo, D.; Lochab, B. Eco-Friendly Halogen-Free Flame Retardant Cardanol Polyphosphazene Polybenzoxazine Networks. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillol, S. Cardanol: A Promising Building Block for Biobased Polymers and Additives. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 14, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzotti, S.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Farina, H.; Disimino, M.; Silvani, A. Carvacrol- And Cardanol-Containing 1,3-Dioxolan-4-Ones as Comonomers for the Synthesis of Functional Polylactide-Based Materials. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 6420–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kim, J.; Kang, E.K.; Park, J.; Cho, J.; Lee, C.; Sohn, E.H.; Lee, J.C. Antibacterial, Antiviral, and Crosslinkable Polymeric Coatings Containing Eco-Friendly Cardanol and Fluoroalkyl Moieties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 203, 109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S.E.; Lomonaco, D.; Mele, G. Óleo da castanha de caju: Oportunidades e desafios no contexto do desenvolvimento e sustentabilidade industrial. Quím. Nova 2009, 32, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.C.; de Morais, S.M.; Magalhães, D.V.; Batista, W.P.; Vieira, Í.G.P.; Craveiro, A.A.; de Manezes, J.E.S.A.; Carvalho, A.F.U.; de Lima, G.P.G. Antioxidant, Larvicidal and Antiacetylcholinesterase Activities of Cashew Nut Shell Liquid Constituents. Acta Trop. 2011, 117, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerasripreecha, D.; Phuwapraisirisan, P.; Puthong, S.; Kimura, K.; Okuyama, M.; Mori, H.; Kimura, A.; Chanchao, C. In Vitro Antiproliferative/Cytotoxic Activity on Cancer Cell Lines of a Cardanol and a Cardol Enriched from Thai Apis Mellifera Propolis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, R.; Alves, N.; Paiva, R.; Valerio, A.; De Oliveira, B.P.; Souza, F.; De Morais, S.M.; Sousa, C.; Abreu, S. Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles for Cardanol-Sustained Delivery System. Polymers 2022, 14, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, R.S.F.; Vieira, R.S.; Luna, F.M.T.; Cavalcante, C.L.; Figueredo, I.M.; Candido, J.R.; Silva, L.P.; Marinho, E.S.; de Lima-Neto, P.; Lomonaco, D.; et al. A Potential Bio-Antioxidant for Mineral Oil from Cashew Nutshell Liquid: An Experimental and Theoretical Approach. Brazilian J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 37, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.P.; Paramashivappa, R.; Vithayathil, P.J.; Rao, P.V.S.; Rao, A.S. Process for Isolation of Cardanol from Technical Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) Nut Shell Liquid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4705–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonaco, D.; Santiago, G.M.P.; Ferreira, Y.S.; Arriaga, Â.M.C.; Mazzetto, S.E.; Mele, G.; Vasapollo, G. Study of Technical CNSL and Its Main Components as New Green Larvicides. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setianto, W.B.; Yoshikawa, S.; Smith, R.L.; Inomata, H.; Florusse, L.J.; Peters, C.J. Pressure Profile Separation of Phenolic Liquid Compounds from Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) Shell with Supercritical Carbon Dioxide and Aspects of Its Phase Equilibria. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2009, 48, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, R.; Tanaka, H.; Uyama, H.; Kobayashi, S. Synthesis and Curing Behaviors of a Crosslinkable Polymer from Cashew Nut Shell Liquid. Polymer 2002, 43, 3475–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.F.; De Lima, P.D.; Martins, L.R.; Beatriz, A.; Santaella, S.T.; Lotufo, V.C.L. Ecotoxicological Analysis of Cashew Nut Industry Effluents, Specifically Two of Its Major Phenolic Components, Cardol and Cardanol. Panam. J. Aquat. Sci. 2009, 4, 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, M.H.; Antônia Maria das Graças Lopes, C.; Lopes, J.A.D.; da Costa, D.A.; de Oliveira, C.A.A.; Costa, A.F.; Brito Júnior, F.E.M. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, F.H.A.; Feitosa, J.P.A.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S.; de França, F.C.F.; Carioca, J.O.B. Antioxidant Activity of Cashew Nut Shell Liquid (CNSL) Derivatives on the Thermal Oxidation of Synthetic Cis-1,4-Polyisoprene. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Arseneault, M.; Sanderson, T.; Murthy, V.; Ramassamy, C. Challenges for Research on Polyphenols from Foods in Alzheimer’s Disease: Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 4855–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Hassan, M.; Ayaz, M. Carotenoid and Phenolic Profiles and Antioxidant and Anticholinesterase Activities of Leaves and Berries of Phytolacca Acinosa. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maqtari, H.M.; Hasan, A.H.; Suleiman, M.; Ahmad Zahidi, M.A.; Noamaan, M.A.; Alexyuk, P.; Alexyuk, M.; Bogoyavlenskiy, A.; Jamalis, J. Benzyloxychalcone Hybrids as Prospective Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors against Alzheimer’s Disease: Rational Design, Synthesis, In Silico ADMET Prediction, QSAR, Molecular Docking, DFT, and Molecular Dynamic Simulation Studies. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 32901–32919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.J.; Goa, K.L. Galantamine: A Review of Its Use in Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs 2000, 60, 1095–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, M.; Lamb, H.M. Donepezil: A Review of Its Use in Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging 2000, 16, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastene-burgos, S.; Muñoz-nuñez, E.; Quiroz-carreño, S.; Pastene-navarrete, E. Ceanothanes Derivatives as Peripheric Anionic Site and Catalytic Active Site Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase: Insights for Future Drug Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochini, C.B.; Lago, J.H.G. Divulgação Aplicação de Técnicas Cromatográ Fi Cas e Espectrométricas Como Ferramentas de Auxílio Na Identi Fi Cação de Componentes de Óleos Voláteis. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2007, 17, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenglin, H.; Ruili, L.; Bao, H.; Liang, M. Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Extracts Prepared from Fresh Leaves of Selected Chinese Medicinal Plants. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.N.; Ferrigni, N.R.; Putnam, J.E.; Jacobsen, L.B.; Nichols, D.E.; McLaughlin, J.L. Brine Shrimp: A Convenient General Bioassay for Active Plant Constituents. J. Med. Plant Res. 1982, 45, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi-Khereshki, N.; Zavvar Mousavi, H.; Farsadrooh, M.; Evazalipour, M.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Mohammadi Ziarani, G.; Henary, M.; Rtimi, S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Biogenic Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for Colorimetric Detection of Fe3+ in Environmental Samples: DFT Calculations and Molecular Docking Studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Mohammadi Ziarani, G.; Lohith, T.N.; Ghareghomi, S.; Panahande, Z.; Farsadrooh, M.; Majidinia, M. Probing the Biological Activity of Isatin Derivatives against Human Lung Cancer A549 Cells: Cytotoxicity, CT-DNA/BSA Binding, DFT/TD-DFT, Topology, ADME-Tox, Docking and Dynamic Simulations. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 428, 127475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahirović, A.; Fetahović, S.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Višnjevac, A.; Bešta-Gajević, R.; Kozarić, A.; Martić, L.; Topčagić, A.; Roca, S. Dual Antimicrobial-Anticancer Potential, Hydrolysis, and DNA/BSA Binding Affinity of a Novel Water-Soluble Ruthenium-Arene Ethylenediamine Schiff Base (RAES) Organometallic. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 318, 124528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahirović, A.; Fetahović, S.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Bešta-Gajević, R.; Dizdar, M.; Ostojić, J.; Roca, S. Substituent Effect in Salicylaldehyde 2-Furoic Acid Hydrazones: Theoretical and Experimental Insights into DNA/BSA Affinity Modulation, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1312, 138628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.; Rudolph, M.J.; Burshteyn, F.; Cassidy, M.S.; Gary, E.N.; Love, J.; Franklin, M.C.; Height, J.J. Structures of Human Acetylcholinesterase in Complex with Pharmacologically Important Ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10282–10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Ben-Shalom, I.Y.; Berryman, J.T.; Brozell, S.R.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham, T.E., III; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; et al. AMBER 2024 Reference Manual; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Software News and Updates Gabedit—A Graphical User Interface for Computational Chemistry Softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.R.; Mcgee, T.D.; Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA. Py: An E Ffi Cient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenidge, P.A.; Kramer, C.; Mozziconacci, J.C.; Wolf, R.M. MM/GBSA Binding Energy Prediction on the PDBbind Data Set: Successes, Failures, and Directions for Further Improvement. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, B.; Amarnath, N.; Rastogi, S.K.; Lochab, B. Isolation of Cardanol Fractions from Cashew Nutshell Liquid (CNSL): A Sustainable Approach. Sustain. Chem. 2024, 5, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Masood, S.; Siddiqui, K.; Alam, M.; Zafar, F.; Rizwanul Haque, Q.M.; Nishat, N. Utilization of Renewable Waste Material for the Sustainable Development of Thermally Stable and Biologically Active Aliphatic Amine Modified Cardanol (Phenolic Lipid)—Formaldehyde Free Standing Films. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1644–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.S.; Palanisamy, A. Synthesis of Bio Based Low Temperature Curable Liquid Epoxy, Benzoxazine Monomer System from Cardanol: Thermal and Viscoelastic Properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 2365–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, S.M.; Silva, K.A.; Araujo, H.; Vieira, I.G.P.; Alves, D.R.; Fontenelle, R.O.S.; Silva, A.M.S. Anacardic Acid Constituents from Cashew Nut Shell Liquid: NMR Characterization and the Effect of Unsaturation on Its Biological Activities. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamed, J.; Chaiyasit, W.; McClements, D.J.; Decker, E.A. Relationships between Free Radical Scavenging and Antioxidant Activity in Foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2969–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korra, S.; Madhurya, S.; Kumar, T.S.; Sainath, A.V.S.; Keshava Murthy, P.S.; Reddy, J.P. Extension of Shelf-Life of Mangoes Using PLA-Cardanol-Amine Functionalized Graphene Active Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 297, 139849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, L.F.N.; De Andrade Ramos, G.; De Oliveira, A.S.; Da Silva, F.M.R.; De Castro Couto, G.; Da Silva Boni, M.; Guimarães, M.J.R.; Souza, I.N.O.; Bartolini, M.; Andrisano, V.; et al. Cardanol-Derived AChE Inhibitors: Towards the Development of Dual Binding Derivatives for Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 108, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Ramos, G.; Souza de Oliveira, A.; Bartolini, M.; Naldi, M.; Liparulo, I.; Bergamini, C.; Uliassi, E.; Wu, L.; Fraser, P.E.; Abreu, M.; et al. Discovery of Sustainable Drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease: Cardanol-Derived Cholinesterase Inhibitors with Antioxidant and Anti-Amyloid Properties. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, A.A.N.; Martins, J.B.L.; dos Santos, M.L.; Nascente, L.d.C.; Romeiro, L.A.S.; Areas, T.F.M.A.; Vieira, K.S.T.; Gambôa, N.F.; Castro, N.G.; Gargano, R. New Potential AChE Inhibitor Candidates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3754–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peak Number | Constituent | Retention Time (min) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cardol triene | 4.59 | 10.39 |

| 2 | Cardol diene | 6.10 | 3.57 |

| 3 | Cardol monoene | 8.93 | 1.16 |

| 4 | Cardanol triene | 10.06 | 36.91 |

| 5 | Cardanol diene | 14.26 | 20.25 |

| 6 | Cardanol monoene | 22.27 | 29.28 |

| Position | Cardanol Monoene (C1) | Cardanol Diene (C2) | Cardanol Triene (C3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dC, Type | dH, (J in Hz) | dC, Type | dH, (J in Hz) | dc, Type | dH, (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 155.66, C | - | 155.65, C | - | 155.95, C | - |

| 2 | 112.69, C | - | 112.69, C | - | 112.77, C | - |

| 3 | 145.14, C | - | 145.12, C | - | 145.02, C | - |

| 4 | 121.16, CH | 6.66, d (10.0) | 121.15, CH | 6.66, d (10.0) | 120.89, CH | 6.67, d (7.5) |

| 5 | 130.36, CH | 7.14, t (7.5) | 130.35, CH | 7.15, t (7.5) | 137.04, CH | 7.13, t (7.5) |

| 6 | 115.52, CH | 6.76, d (10.0) | 115.51, CH | 6.77, d (5.0) | 115.58, CH | 6.74, d (7.5) |

| 1′ | 36.04, CH2 | 2.57, t (7.5) | 36.02, CH2 | 2.56, q (7.5) | 36.04, CH2 | 2.58, t (7.5) |

| 2′ | 31.49, CH2 | 1.61, q (5.0) | 31.48, CH2 | 1.60, q (5.0) | 31.46, CH2 | 1.59, q (6.0) |

| 3′, 4′ 5′, 6′ | 29.21–29.96, CH2 | 1.27–1.41 | 29.20–29.95, CH2 | 1.27–1.42 | 29.42–29.82, CH2 | 1.33 (8.0) |

| 7′ | 27.45, CH2 | 2.03, bq (12.5) | 27.43, CH2 | 2.05, bq (10.0) | 27.43, CH2 | 2.06, bq (6.0) |

| 8′ | 130.06, CH | 5.38, bt (6.0) | 130.06, CH | 5.32–5.43, m | 130.61, CH | 5.31–5.50, m |

| 9′ | 129.59, CH | 5.36, bq (6.0) | 130.06, CH | 5.32–5.43, m | 130.61, CH | 5.31–5.50, m |

| 10′ | 27.41, CH2 | 2.03, m | 32.00, CH2 | 2.79, t (5.0) | 31.76, CH2 | 2.82, m |

| 11′ | 29.21–29.96, CH2 | 1.27–1.41, m | 128.22, CH | 5.32–5.43, m | 127.80–127.05, CH | 5.31–5.50, m |

| 12′ | 29.21–29.96, CH2 | 1.27–1.41, m | 128.22, CH | 5.32–5.43, m | 127.80–127.05, CH | 5.31–5.50, m |

| 13′ | 29.21–29.96, CH2 | 1.27–1.41, m | 27.43, CH2 | 1.27–1.42, m | 25.78, CH2 | 2.82, m |

| 14′ | 29.21–29.96, CH2 | 1.27–1.41, m | 29.20–29.95, CH2 | 1.27–1.42, m | 137.04–114.90, CH | 5.83, m |

| 15′ | 14.02, CH3 | 0.91, t (15.0) | 14.02, CH3 | 0.91, t (15.0) | 137.04–114.90, CH2 | 5.07, dd (5.3) 4.99, d (9.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues Valério, R.B.; de Souza, H.; Martins, V.; Silva, K.; de Manezes, J.E.; Chaves, A.; Serafim, L.F.; Vieira-Neto, A.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; de Morais, S. Unsaturation-Driven Modulation of Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activities of Cardanol Derivatives. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121316

Rodrigues Valério RB, de Souza H, Martins V, Silva K, de Manezes JE, Chaves A, Serafim LF, Vieira-Neto A, dos Santos JCS, de Morais S. Unsaturation-Driven Modulation of Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activities of Cardanol Derivatives. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(12):1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121316

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues Valério, Roberta Bussons, Halisson de Souza, Vitor Martins, Katherine Silva, Jane Eire de Manezes, Anderson Chaves, Leonardo F. Serafim, Antônio Vieira-Neto, José Cleiton S. dos Santos, and Selene de Morais. 2025. "Unsaturation-Driven Modulation of Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activities of Cardanol Derivatives" Bioengineering 12, no. 12: 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121316

APA StyleRodrigues Valério, R. B., de Souza, H., Martins, V., Silva, K., de Manezes, J. E., Chaves, A., Serafim, L. F., Vieira-Neto, A., dos Santos, J. C. S., & de Morais, S. (2025). Unsaturation-Driven Modulation of Antioxidant and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activities of Cardanol Derivatives. Bioengineering, 12(12), 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121316