The Development and Evaluation of a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model Virtual Assistant for Postoperative Instructions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Limitations of Current Patient Education Methods

1.3. The Promise of AI in Postoperative Care

1.4. The Evolution of AI Virtual Assistant

1.5. Study Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Knowledge Base Development

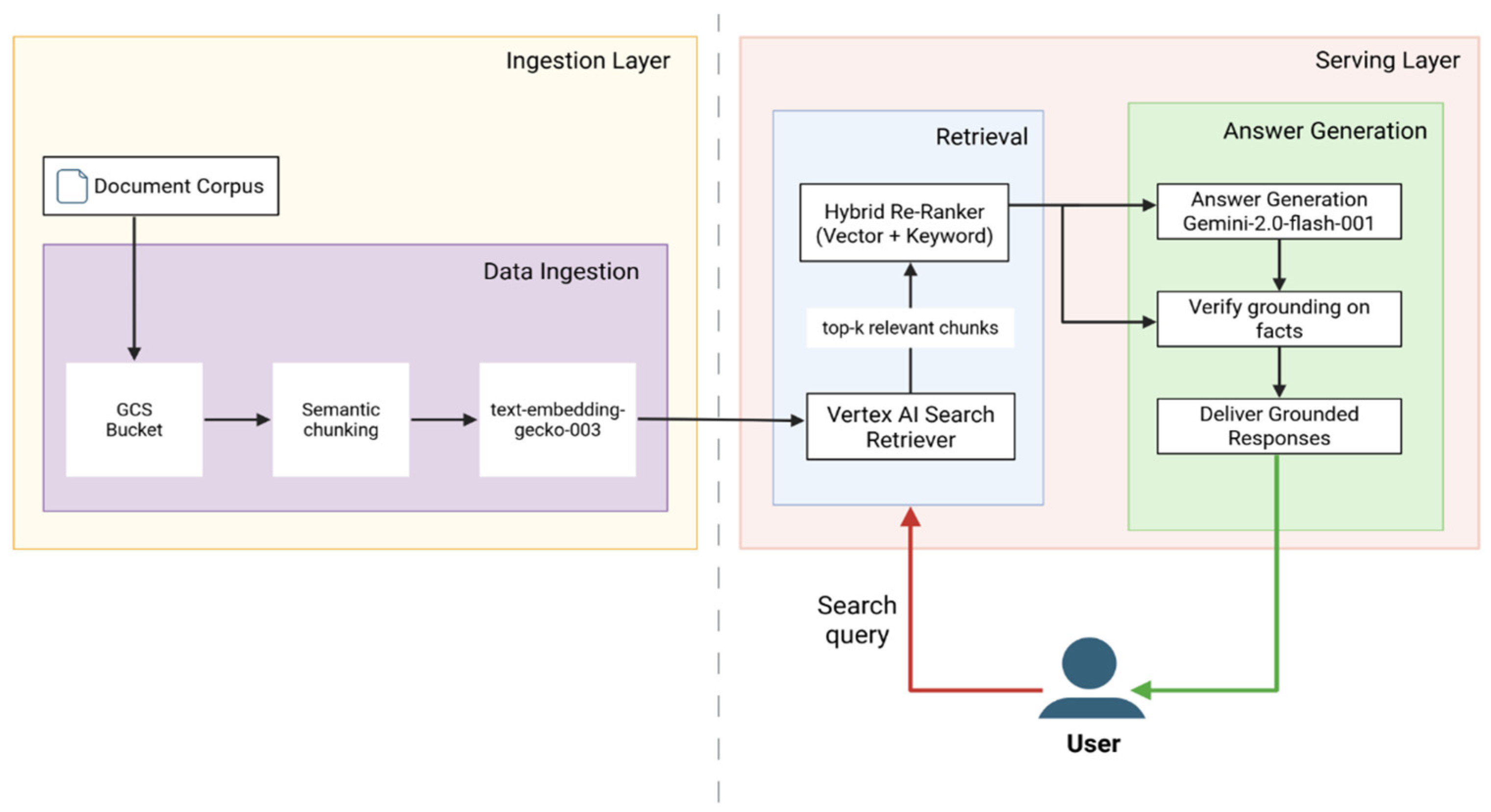

2.3. System Architecture

2.3.1. Ingestion Layer—Knowledge Base Preparation

2.3.2. Serving Layer—User Query Processing and Response Generation

Retrieval Path

Answer Generation Path

2.3.3. Embedded Safety Features

2.4. Test Question Corpus

2.5. Evaluation Procedures

2.5.1. Human Expert Evaluation

2.5.2. Automated and Algorithmic Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Human Expert Evaluation Results

3.1.1. Accuracy (Classification)

3.1.2. Human Quality Ratings (Completeness, Consistency, Relevance)

3.1.3. Inter-Rater Reliability

3.1.4. System Safety and Robustness (Human-Reviewed Aspects)

3.2. Automated LLM Metrics Results

3.2.1. Linguistic Fluency, Syntax and Readability

3.2.2. Groundedness

4. Discussion

4.1. Advancement Beyond Earlier AIVA Iterations

4.2. Addressing LLM Safety Gaps: Retrieval-Augmented Generation as a Scalable Clinical Framework

4.3. Readability Remains a Key Optimization Target

4.4. Study Limitations

4.5. Ethical Considerations

4.6. Future Directions

4.7. Generalizability to Other Clinical Domains

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meara, J.G.; Leather, A.J.; Hagander, L.; Alkire, B.C.; Alonso, N.; Ameh, E.A.; Bickler, S.W.; Conteh, L.; Dare, A.J.; Davies, J.; et al. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015, 386, 569–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, G.P. Trauma of major surgery: A global problem that is not going away. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 81, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, J.I.; Lan, W.C.; Chung, K.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Sears, E.D. The Increasing Financial Burden of Outpatient Elective Surgery for the Privately Insured. Ann. Surg. 2020, 272, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, A.; Cheung, K.; Wu, C.L.; Stierer, T.S. Burden incurred by patients and their caregivers after outpatient surgery: A prospective observational study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014, 472, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apfelbaum, J.L.; Chen, C.; Mehta, S.S.; Gan, T.J. Postoperative pain experience: Results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth. Analg. 2003, 97, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.; Ormel, I.; Babinski, S.; Kuluski, K.; Quesnel-Vallée, A. “Caregiving is like on the job training but nobody has the manual”: Canadian caregivers’ perceptions of their roles within the healthcare system. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barutcu, C.D. Relationship between caregiver health literacy and caregiver burden. Puerto Rico Health Sci. J. 2019, 38, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, B.; Rodakowski, J.; James, A.E.; Beach, S. Caregiver health literacy predicting healthcare communication and system navigation difficulty. Fam. Syst. Health 2018, 36, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng-Treitler, Q.; Kim, H.; Hunter, M. Improving patient comprehension and recall of discharge instructions by supplementing free texts with pictographs. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2008, 2008, 849–853. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, D.M.; Waite, K.R.; Curtis, L.M.; Engel, K.G.; Baker, D.W.; Wolf, M.S. What did the doctor say? Health literacy and recall of medical instructions. Med. Care 2012, 50, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, A.J.; Wang, L.; Go, M.; Eggers, Z.; Deng, R.; Maggio, P.; Shieh, L. Night-time communication at Stanford University Hospital: Perceptions, reality and solutions. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018, 27, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J. Burnout Related to Electronic Health Record Use in Primary Care. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231166921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicourel, A.V. Cognitive overload and communication in two healthcare settings. Commun. Med. 2004, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, R.W.; Haskell, J.; Gardner, R.L. Are specific elements of electronic health record use associated with clinician burnout more than others? J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloy-Prósper, A.; Pellicer-Chover, H.; Balaguer-Martínez, J.; Llamas-Monteagudo, O.; Peñarrocha-Diago, M. Patient compliance to postoperative instructions after third molar surgery comparing traditional verbally and written form versus the effect of a postoperative phone call follow-up a: A randomized clinical study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2020, 12, e909–e915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzynski, E.; Hashmi, H.; Subramanian, J.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Polverento, M.; Simmons, M.; Brooks, K.; Given, C. Opportunities to improve clinical summaries for patients at hospital discharge. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laippala, V.; Danielsson-Ojala, R.; Lundgrén-Laine, H.; Salanterä, S.; Salakoski, T. Vocabulary In Discharge Documents The Patient’s Perspective. In Proceedings of the CLEF (Online Working Notes/Labs/Workshop), Rome, Italy, 17–20 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K.R. Patient-perceived facilitators of and barriers to electronic portal use: A systematic review. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2017, 35, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoonakker, P.L.; Rankin, R.J.; Passini, J.C.; Bunton, J.A.; Ehlenfeldt, B.D.; Dean, S.M.; Thurber, A.S.; Kelly, M.M. Nurses’ expectations of an inpatient portal for hospitalized patients and caregivers. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2019, 10, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, J.; Gruber-Baldini, A.; Hirshon, J.; Brown, C.; Goldberg, R.; Rosenberg, J.; Comer, A.; Furuno, J. Hospital discharge instructions: Comprehension and compliance among older adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubb, S.; Kaur, G.; Kumari, S.; Murti, K.; Pal, B. Comprehension and compliance with discharge instructions among pediatric caregivers. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 17, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Borna, S.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, S.A.; Sehgal, A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Forte, A.J. Artificial Intelligence in Postoperative Care: Assessing Large Language Models for Patient Recommendations in Plastic Surgery. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, S.; Bahar, H.; Yavuz, U.; Keskin, A.; Karslioglu, B.; Solak, Y. Comparative Efficacy of ChatGPT and DeepSeek in Addressing Patient Queries on Gonarthrosis and Total Knee Arthroplasty. Arthroplast. Today 2025, 33, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Rupavath, R.V.S.S.B.; Jalaja, P.P.; Ushmani, A.; Mishra, A.; Bodapati, N.V.S.B.; Agrawal, S.K.; Bodapati, N.V.S.B. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Driven Approaches to Manage Postoperative Pain, Anxiety, and Psychological Outcomes in Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e84226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.J.; Rohrich, R. Artificial intelligence and postoperative monitoring in plastic surgery. Plast. Surg. 2025, 33, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Xie, R.; Guo, Q.; He, Y.; Wu, H. The Potential of GPT-4 as an AI-Powered Virtual Assistant for Surgeons Specialized in Joint Arthroplasty. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 1366–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E. Redefining Virtual Assistants in Health Care: The Future With Large Language Models. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e53225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachten, F.; Brünker, F.; Frick, N.R.; Ross, B.; Stieglitz, S. On the ability of virtual agents to decrease cognitive load: An experimental study. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2020, 18, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, M.H.; Handiyani, H.; Nuraini, T.; Hariyati, R.T.S.; Sutrisno, S. A systematic review of artificial intelligence-powered (AI-powered) chatbot intervention for managing chronic illness. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2302980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, S.; Lozano, M.L.; García, J.; Alesanco, Á. Validation of a virtual assistant for improving medication adherence in patients with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus and depressive disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gonzalez, P.; He, A.W.; Lam, E.P.; Ng, I.M.C.; Li, M.W.; Hou, R.; Chan, J.N.; Sahni, Y.; Vinas Guasch, N.; Miller, T.; et al. Artificial intelligence in mental health care: A systematic review of diagnosis, monitoring, and intervention applications. Psychol. Med. 2025, 55, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, E.; Charness, N.; Boot, W. Are virtual assistants trustworthy for Medicare information: An examination of accuracy and reliability. The Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnae062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczar, D.; Sisti, A.; Oliver, J.D.; Helmi, H.; Restrepo, D.J.; Huayllani, M.T.; Spaulding, A.C.; Carter, R.; Rinker, B.D.; Forte, A.J. Artificial intelligent virtual assistant for plastic surgery patient’s frequently asked questions: A pilot study. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 84, e16–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, F.R.; Boczar, D.; Spaulding, A.C.; Quest, D.J.; Samanta, A.; Torres-Guzman, R.A.; Maita, K.C.; Garcia, J.P.; Eldaly, A.S.; Forte, A.J. High satisfaction with a virtual assistant for plastic surgery frequently asked questions. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2023, 43, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.A.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, C.R.; Forte, A.J. The algorithmic divide: A systematic review on AI-driven racial disparities in healthcare. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, S.A.; Sehgal, A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Cole, D.; Forte, A.J. Comparative analysis of artificial intelligence virtual assistant and large language models in post-operative care. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, A.; Prabha, S.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Haider, S.A.; Trabilsy, M.; Tao, C.; Aziz, K.T.; Murray, P.M.; Forte, A.J. Artificial Intelligence for Patient Support: Assessing Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Answering Postoperative Rhinoplasty Questions. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2025, 45, sjaf038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozmen, B.B.; Singh, N.; Shah, K.; Berber, I.; Singh, F.D.; Pinsky, E.; Rampazzo, A.; Schwarz, G.S. Development of A Novel Artificial Intelligence Clinical Decision Support Tool for Hand Surgery: HandRAG. J. Hand Microsurg. 2025, 17, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, C.S.; Obey, N.T.; Zheng, Y.; Cohan, A.; Schneider, E.B. SurgeryLLM: A retrieval-augmented generation large language model framework for surgical decision support and workflow enhancement. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, B.D.; Kuderer, N.M.; Bacchi, S.; Modi, N.D.; Chin-Yee, B.; Hu, T.; Rickard, C.; Haseloff, M.; Vitry, A.; McKinnon, R.A. Current safeguards, risk mitigation, and transparency measures of large language models against the generation of health disinformation: Repeated cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2024, 384, e078538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, P.; Maurer, E.; Dwivedi, R. The urgency of centering safety-net organizations in AI governance. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznietsov, A.; Gyevnar, B.; Wang, C.; Peters, S.; Albrecht, S.V. Explainable AI for safe and trustworthy autonomous driving: A systematic review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 19342–19364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. Google Vertex AI Studio. 2025. Available online: https://console.cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/studio/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Abbasian, M.; Khatibi, E.; Azimi, I.; Oniani, D.; Shakeri Hossein Abad, Z.; Thieme, A.; Sriram, R.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, B. Foundation metrics for evaluating effectiveness of healthcare conversations powered by generative AI. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoppilan, R.; De Freitas, D.; Hall, J.; Shazeer, N.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Cheng, H.-T.; Jin, A.; Bos, T.; Baker, L.; Du, Y. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.08239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, R.; Wu, Z.; Gulley, A.; Hilliard, A.; Guan, X.; Koshiyama, A.; Treleaven, P. HyPA-RAG: A Hybrid Parameter Adaptive Retrieval-Augmented Generation System for AI Legal and Policy Applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.09046. [Google Scholar]

- Es, S.; James, J.; Anke, L.E.; Schockaert, S. Ragas: Automated evaluation of retrieval augmented generation. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, St. Julian’s, Malta, 17–22 March 2024; pp. 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Nasa, P.; Jain, R.; Juneja, D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J. Methodol. 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.A.; Pressman, S.M.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Sehgal, A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Forte, A.J. Evaluating Large Language Model (LLM) Performance on Established Breast Classification Systems. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Huang, J.; Ji, M.; Yang, Y.; An, R. Use of Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Model for COVID-19 Fact-Checking: Development and Usability Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e66098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Song, J.; Kim, M.-G.; Yu, H.W.; Choe, E.K.; Chai, Y.J. Thyro-GenAI: A Chatbot Using Retrieval-Augmented Generative Models for Personalized Thyroid Disease Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Sun, S.; Owens, J.; Galvez, V.; Gologorskaya, O.; Lai, J.C.; Pletcher, M.J.; Lai, K. Development of a liver disease–specific large language model chat interface using retrieval-augmented generation. Hepatology 2024, 80, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinostroza Fuentes, V.G.; Karim, H.A.; Tan, M.J.T.; AlDahoul, N. AI with agency: A vision for adaptive, efficient, and ethical healthcare. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1600216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaddad, M.; Hamam, S. AI-driven clinical decision support systems: An ongoing pursuit of potential. Cureus 2024, 16, e57728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liawrungrueang, W. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Agents Versus Agentic AI: What’s the Effect in Spine Surgery? Neurospine 2025, 22, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, W.; Lv, B.; Liu, M.; Kong, X.; Zhao, C.; Pan, Z. A large language model for multimodal identification of crop diseases and pests. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, C.; Li, J. Agri-QA Net: Multimodal Fusion Large Language Model Architecture for Crop Knowledge Question-Answering System. Smart Agric. 2025, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; McCoy, A.B.; Wright, A. Improving large language model applications in biomedicine with retrieval-augmented generation: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and clinical development guidelines. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, ocaf008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Thongprayoon, C.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Garcia Valencia, O.A.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Integrating retrieval-augmented generation with large language models in nephrology: Advancing practical applications. Medicina 2024, 60, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargari, O.K.; Habibi, G. Enhancing medical AI with retrieval-augmented generation: A mini narrative review. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076251337177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templin, T.; Perez, M.W.; Sylvia, S.; Leek, J.; Sinnott-Armstrong, N. Addressing 6 challenges in generative AI for digital health: A scoping review. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.G.; Babic, B.; Gerke, S.; Xia, Q.; Evgeniou, T.; Wertenbroch, K. How AI can learn from the law: Putting humans in the loop only on appeal. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, M.; Ma, W.; Liu, X. Application of AI Chatbot in Responding to Asynchronous Text-Based Messages From Patients With Cancer: Comparative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e67462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Bozic, K.J.; Jayakumar, P. Artificial Intelligence in Value-Based Health Care. HSS J. 2025, 21, 15563316251340074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Current Limitation | Impact on Patients/ Providers | Gap Addressed by AIVA |

|---|---|---|

| Static, text-heavy handouts/portals | Low engagement; poor comprehension | Interactive, conversational guidance |

| Complex medical jargon | Exceeds health literacy levels | Simplified, patient-friendly responses |

| Non-adaptable, generic content | Limited personalization | Context-specific, procedure-tailored answers |

| No interactivity or Q&A | Patient uncertainty, frequent calls | Dynamic query handling, immediate clarification |

| Limited access outside clinic hours | After-hours anxiety, ED overutilization | 24/7 continuous availability |

| No. | Topic | No. | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pain and Pain Management | 11 | Showering and Bathing |

| 2 | Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) | 12 | Emotional Wellbeing/Body image after surgery |

| 3 | Drain Management | 13 | Sleep Disturbance |

| 4 | Follow-up Appointments | 14 | Need for Home Assistance |

| 5 | Postoperative recovery and recovery timeline (fatigue, swelling, bruising) | 15 | Surgical Garments |

| 6 | Diet/Food to eat after surgery | 16 | Traveling |

| 7 | Resuming Physical activity (Gym, Weights) | 17 | Additional Treatments (Radiation/Chemo, etc.) |

| 8 | Scars | 18 | Alarm Signs |

| 9 | Sutures, Staples | 19 | Wound Care |

| 10 | Sexual Activity | 20 | Return to Work |

| Query Category | Base Queries (n) | +Paraphrase Variants (×2) | Total Queries (3 Variants: Base + Paraphrase) |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-Scope Clinical Queries | 200 | +400 | 600 (200 + 400) |

| Out-of-Scope Queries | 40 | +80 | 120 (40 + 80) |

| Escalation Scenarios | 10 | +20 | 30 (10 + 20) |

| Total | 250 | +500 | 750 (500 + 250) |

| Metric | Queries (n) | Subset | Rules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 250 | Base queries only | Binary (0, 1) |

| Completeness | 250 | Base queries only | Likert (1–5) |

| Relevance (SSI) | 250 | Base queries only | SSI Scale (0–3) |

| Consistency | 750 | All queries (250 base + 500 paraphrased queries) | Likert (1–5) |

| Inter-rater Reliability | 250 | Base queries only | - |

| Predicted Positive | Predicted Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Positive | 196 (TP) | 4 (FN) |

| Actual Negative | 0 (FP) | 50 (TN) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haider, S.A.; Prabha, S.; Gomez Cabello, C.A.; Genovese, A.; Collaco, B.; Wood, N.; London, J.; Bagaria, S.; Tao, C.; Forte, A.J. The Development and Evaluation of a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model Virtual Assistant for Postoperative Instructions. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111219

Haider SA, Prabha S, Gomez Cabello CA, Genovese A, Collaco B, Wood N, London J, Bagaria S, Tao C, Forte AJ. The Development and Evaluation of a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model Virtual Assistant for Postoperative Instructions. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(11):1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111219

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Syed Ali, Srinivasagam Prabha, Cesar Abraham Gomez Cabello, Ariana Genovese, Bernardo Collaco, Nadia Wood, James London, Sanjay Bagaria, Cui Tao, and Antonio Jorge Forte. 2025. "The Development and Evaluation of a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model Virtual Assistant for Postoperative Instructions" Bioengineering 12, no. 11: 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111219

APA StyleHaider, S. A., Prabha, S., Gomez Cabello, C. A., Genovese, A., Collaco, B., Wood, N., London, J., Bagaria, S., Tao, C., & Forte, A. J. (2025). The Development and Evaluation of a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model Virtual Assistant for Postoperative Instructions. Bioengineering, 12(11), 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12111219