Clinical Application of Bioresorbable, Synthetic, Electrospun Matrix in Wound Healing

Abstract

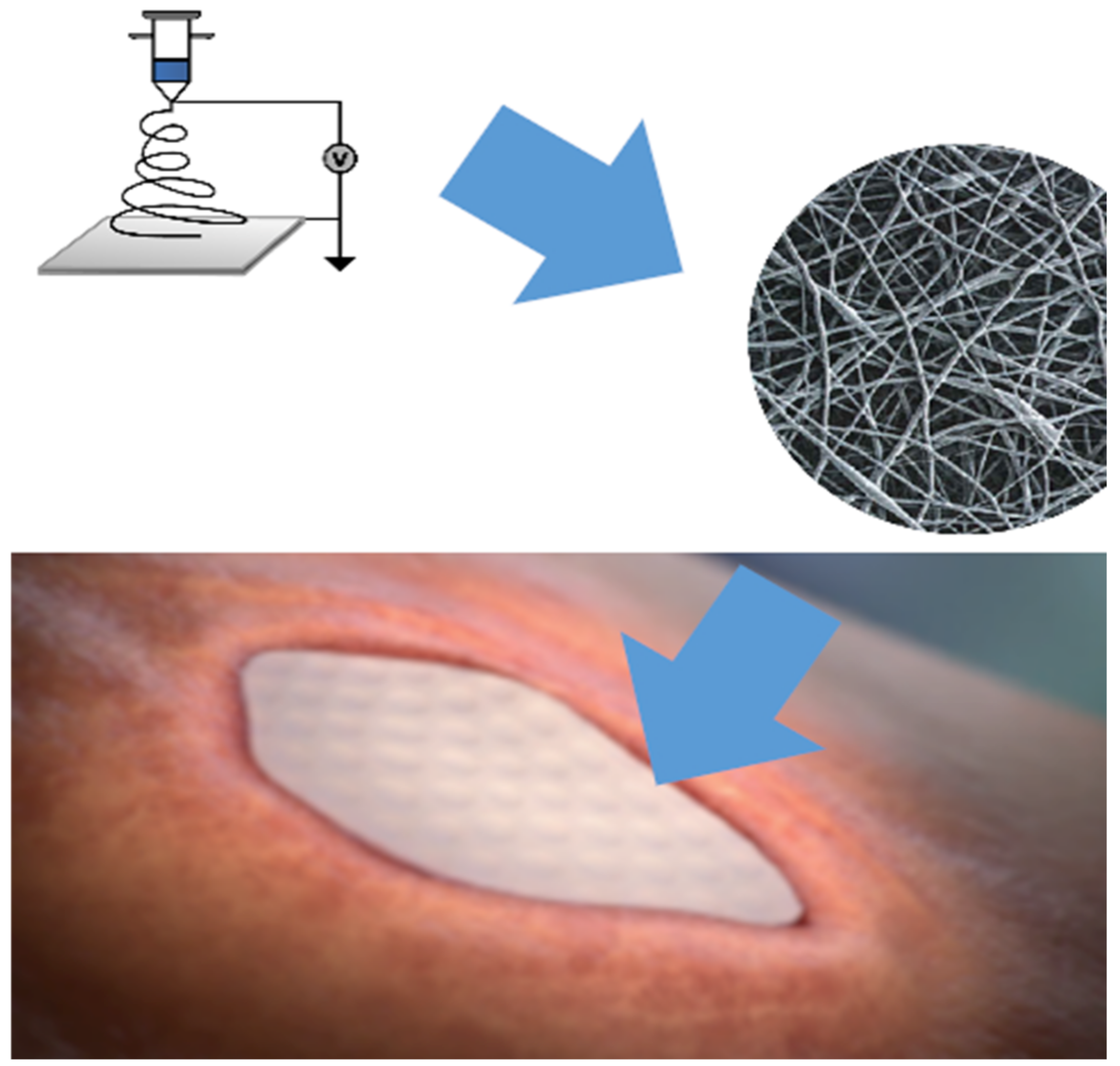

1. Introduction

2. Material Fabrication and Methods

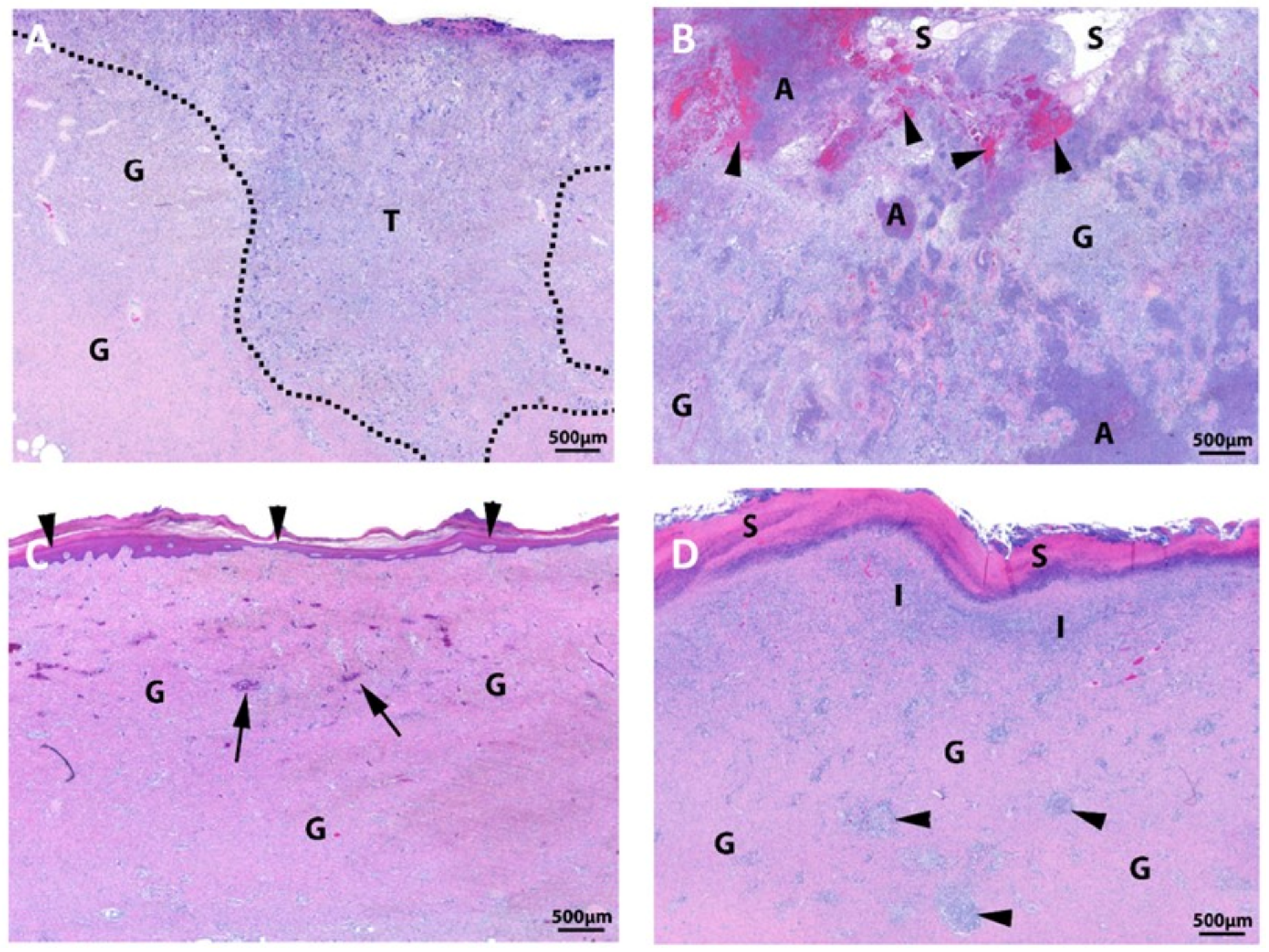

3. Preclinical Results

3.1. Biocompatibility Studies

3.2. pH Study

3.3. Large Animal Study

4. Clinical Assessments/Studies

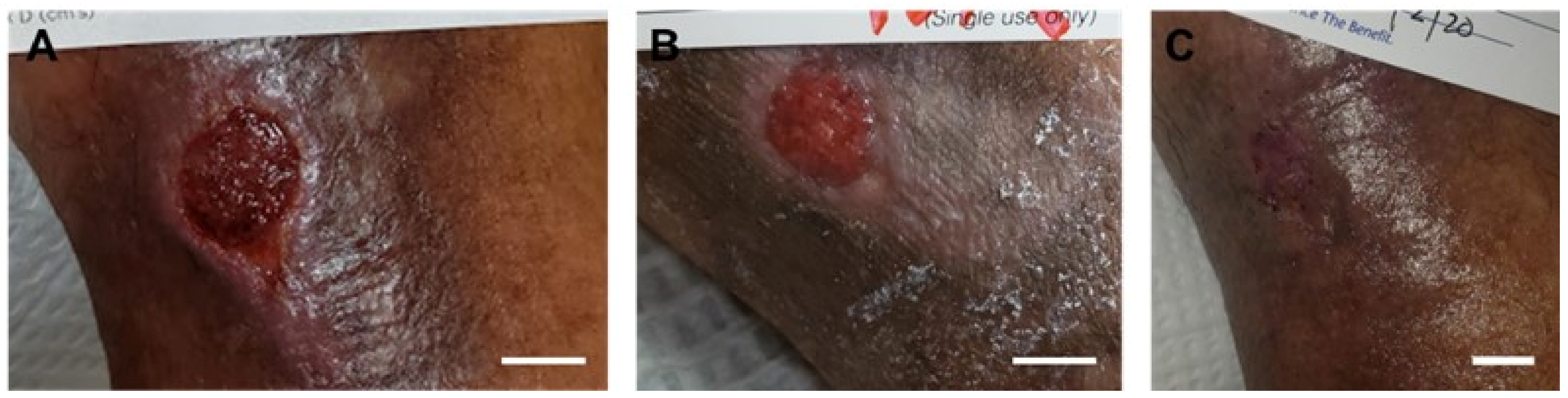

4.1. Chronic Wound Care

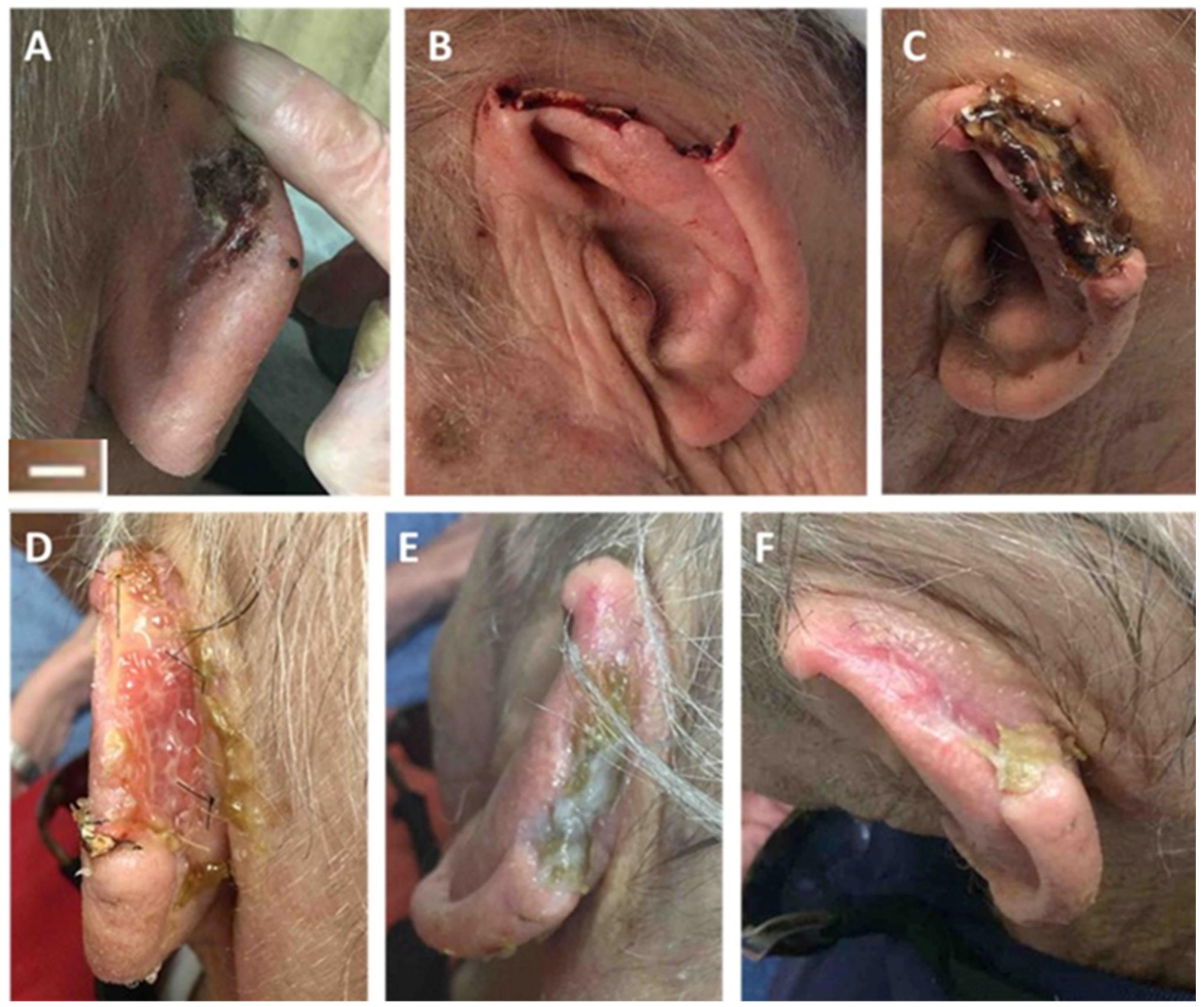

4.2. Post-Mohs Wounds

4.3. Tendon Healing

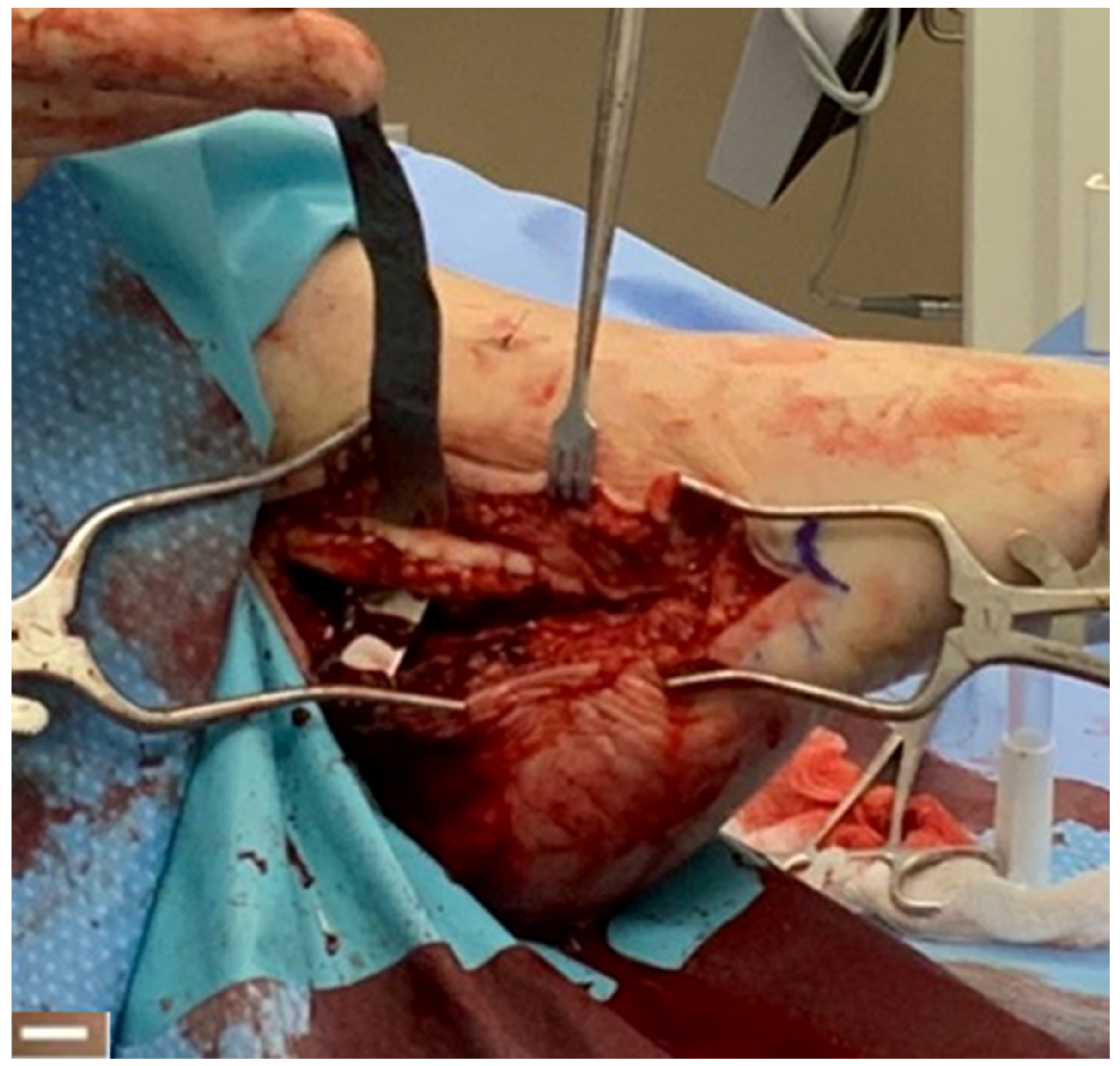

4.4. Traumatic Wounds

4.5. Other Wounds

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frykberg, R.G.; Banks, I. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv. Wound Care. 2015, 118, 560–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalezari, S.; Lee, C.J.; Borovikova, A.A.; Banyard, D.; Paydar, K.Z.; Wirth, G.A.; Widgerow, A.D. Deconstructing negative pressure wound therapy. Int. Wound J. 2017, 14, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, F.; Soleimaninejad, M. Role of growth factors and biomaterials in wound healing. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Grimalt, R. A review of platelet-rich plasma: History, biology, mechanism of action, and classification. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ramakrishna, S.; Liu, X. Electrospinning and emerging healthcare and medicine possibilities. APL Bioeng. 2020, 4, 030901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.P.; Sell, S.A.; Boland, E.D.; Simpson, D.G.; Bowlin, G.L. Nanofiber technology: Designing the next generation of tissue engineering scaffolds. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 59, 1413–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sill, T.J.; Recum, H.A. Electrospinning: Applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hua, S.; Yang, M.; Fu, Z.; Teng, S.; Niu, K.; Zhao, Q.; Yi, C. Fabrication and characterization of electrospinning/3D printing bone tissue engineering scaffold. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 110557–110565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Mo, X.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, G. 3D printing electrospinning fiber-reinforced decellularized extracellular matrix for cartilage regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, N.; Sawadkar, P.; Ho, S.; Sharma, V.; Snow, M.; Powell, S.; Woodruff, M.A.; Hook, L.; García-Gareta, E. Pre-screening the intrinsic angiogenic capacity of biomaterials in an optimised ex ovo chorioallantoic membrane model. J. Tissue Eng. 2020, 11, 2041731420901621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbar, S.G.; Nukavarapu, S.P.; James, R.; Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Electrospun poly-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid scaffolds for skin tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 4100–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottosson, M.; Jakobsson, A.; Johansson, F. Accelerated wound closure—Differently organized nanofibers affect cell migration and hence the closure of artificial wounds in a cell based in vitro model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, I.; Han, H.-S.; Edwards, J.R.; Jeon, H. Electrospun fibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering: Viewpoints on architecture and fabrication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorth, D.; Webster, T.J. Matrices for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. In Biomaterial Artificial Organs, 1st ed.; Lysaght, M., Webster, T.J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 270–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S.P.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Lim, C.T. Tissue scaffolds for skin wound healing and dermal reconstruction. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 2, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K.; Feijoo, J.L.; Yang, M. Comparison of abiotic and biotic degradation of PDLLA, PCL, and partially miscible PDLLA/PCL blend. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEwan, M.R.; MacEwan, S.; Kovacs, T.R.; Batts, J. What makes the optimal wound healing material? A review of current science and introduction of a synthetic nanofabricated wound care scaffold. Cureus 2017, 9, e1736–e1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Jones, K.S. Effect of alginate on innate immune activation of macrophages. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2009, 90, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.P.; Sharma, U.; Mikos, A.G. Electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/ microfiber scaffolds: Characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 2796–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chang, T.; Yang, H.; Cui, M. Antibacterial mechanism of lactic acid on physiological and morphological properties of Salmonella Enteritidis, Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 2015, 47, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, A.; Bhalla, P.; Sharma, K.B. Evaluation of lactic acid as an antibacterial agent. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 1979, 45, 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, C.R.; Nuutila, K.; Lee, C.C.; Kiwanuka, E.; Singh, M.; Caterson, E.J.; Eriksson, E.; Sørensen, J.A. The external microenvironment of healing skin wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watters, C.; Yuan, C.; Rumbaugh, K. Beneficial and deleterious bacterial–host interactions in chronic wound pathophysiology. Chronic Wound Care Manag. Res. 2015, 2, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hostacká, A.; Ciznár, M.; Stefkovicová, M. Temperature and pH affect the production of bacterial biofilm. Folia Microbiol. 2010, 55, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagoba, B.S.; Suryawanshi, N.M.; Wadher, B.; Sohan, S. Acidic environment and wound healing: A review. Wounds 2015, 27, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vilchez, A.; Acevedo, F.; Cea, M.; Seeger, M.; Navia, R. Applications of electrospun nanofibers with antioxidant properties: A review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhari, N.; Hashim, N.; Md Akim, A.; Maringgal, B. Recent advances in honey-based nanoparticles for wound dressing: A review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, M.; Wu, S. State-of-the-Art review of electrospun Gelatin based nanofiber dressings for wound healing applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. 510(K) Premarket Notification. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K170300 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- MacEwan, M.R.; MacEwan, S.; Wright, A.P.; Kovacs, T.R.; Batts, J.; Zhang, L. Comparison of a fully synthetic electrospun matrix to a bi-layered xenograft in healing full thickness cutaneous wounds in a porcine model. Cureus 2017, 9, E1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulski, M.J.; MacEwan, M.R. Implantable nanomedical scaffold facilitates healing of chronic lower extremity wounds. Wounds 2018, 30, E77–E80. [Google Scholar]

- Killeen, A.L.; Brock, K.M.; Loya, R.; Honculada, C.S.; Houston, P.; Walters, J.L. Fully synthetic bioengineered nanomedical scaffold in chronic neuropathic foot ulcers. Wounds 2018, 30, E98–E101. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, E.C.; Abicht, B.P. Lower extremity wounds treated with a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. Foot Ankle Surg. Tech. Rep. Cases 2021, 1, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abicht, B.P.; Deitrick, G.A.; MacEwan, M.R.; Jeng, L. Evaluation of wound healing of diabetic foot ulcers in a prospective clinical trial using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. Foot Ankle Surg. Tech. Rep. Cases 2022, 2, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, K. Clinical impact of a novel synthetic nanofibre matrix to treat hard-to-heal wounds. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallery, M.; Shannon, T. Augmented flap reconstruction of complex pressure ulcers using synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. Wounds 2022, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, K. Treatment of complex lower extremity wounds utilizing synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, D. Clinical evaluation of a synthetic hybrid-scale matrix in the treatment of lower extremity surgical wounds. Cureus 2022, 14, e27452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; Desai, V.; Denden, S.; Alianello, N. Assessment of a novel augmented closure technique for surgical wounds associated with transmetatarsal amputation: A preliminary study. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2022, 112, 20–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J. Reconstruction of post-Mohs surgical wounds using a novel nanofiber matrix. Wounds 2022, 34, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, E.; Jones, N.; Prusa, R.; Brandt, M. Peroneal tendon repair using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix: A case series. Foot Ankle Surg 2022, 2, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L.; Shar, A.; Matthews, M.R.; Kim, P.; Thompson, C.; Williams, N.; Stutsman, M. Synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix in the trauma and acute care surgical practice. Wounds 2021, 33, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, C.J.; Burgess, B.; Ghodasra, J.H. Treatment of traumatic crush injury using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix in conjunction with split-thickness skin graft. Foot Ankle Surg. Tech. Rep. Cases 2022, 2, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, E. Treatment of hematomas using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. Cureus 2022, 14, e26491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyhani, S.; Mardani-Kivi, M.; Abbasian, M.; Tehrani, M.E.M.; Lahiji, F.A. Achilles tendon repair, a modified technique. Arch. Bone. Jt. Surg. 2013, 1, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, J.E.; Schmitt, B.J.; Wagstaff, M.J. Experience with a synthetic bilayer biodegradable temporising matrix in significant burn injury. Burn. Open 2018, 2, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Weis, T.L.; Schurr, M.J.; Faith, N.G.; Czuprynski, C.J.; McAnulty, J.F.; Murphy, C.J.; Abbott, N.L. Surfaces modified with nanometer-thick silver-impregnated polymeric films that kill bacteria but support growth of mammalian cells. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, V.R.; Lavery, L.A.; Reyzelman, A.M.; Dutra, T.G.; Dove, C.R.; Kotsis, S.V.; Kim, H.M.; Chung, K.C. A clinical trial of Integra Template for diabetic foot ulcer treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, D.J.; Kantor, J.; Berlin, A. Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard treatment. A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, M. European and Australian Apligraf Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. Apligraf in the treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. Int. J. Low Extrem. Wounds 2009, 8, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiDomenico, L.; Landsman, A.R.; Emch, K.J.; Landsman, A. A prospective comparison of diabetic foot ulcers treated with either a cryopreserved skin allograft or a bioengineered skin substitute. Wounds 2011, 23, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, W.A.; Hanft, J.; Norwood, P.; Pollak, R.; Dermagraft Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. The efficacy and safety of Dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: Results of a prospective randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulski, M.; Jacobstein, D.A.; Petranto, R.D.; Migliori, V.J.; Nair, G.; Pfeiffer, D. A retrospective analysis of a human cellular repair matrix for the treatment of chronic wounds. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2013, 59, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Cazzell, S.; Vayser, D.; Reyzelman, A.M.; Dosluoglu, H.; Tovmassian, G.; EpiFix VLU Study Group. A multicentre randomised controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane (EpiFix®) allograft for the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2018, 15, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, T.E.; Carter, M.J.; Le, L.T.; Sabo, M.J.; DiMarco, D.T.; EpiFix VLU Study Group. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial evaluating the use of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allografts and multilayer compression therapy vs. multilayer compression therapy alone in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2014, 22, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, K.; Sumner, M.; Cardinal, M. A prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled study of human fibroblast-derived dermal substitute (Dermagraft) in patients with venous leg ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2013, 10, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Etris, M.; Milne, C.T.; Hodde, J.P. An extracellular matrix graft (Oasis® wound matrix) for treating full-thickness pressure ulcers: A randomized clinical trial. J. Tissue Viability 2019, 28, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alet, J.M.; Michot, A.; Desnouveaux, E.; Fleury, M.; Téot, L.; Fluieraru, S.; Casoli, V. Collagen regeneration template in the management of full-thickness wounds: A prospective multicentre study. J. Wound Care 2019, 28, S22–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.R.; Perkins, J.M.; Magee, T.R.; Galland, R.B. Transmetatarsal amputation: An 8-year experience. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2001, 83, 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, G.J.; Silverman, D.A.; Lie, T.K.; Mitchell, E.L.; Moneta, G.L. Predictors of healing and functional outcome following transmetatarsal amputations. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudkiewicz, I.; Schwarz, O.; Heim, M.; Herman, A.; Siev-Ner, I. Trans-metatarsal amputation in patients with a diabetic foot: Reviewing 10 years experience. Foot 2019, 19, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Supplier Information | Material Source (Allograft, Xenograft, or Synthetic) | Composition (Bovine Collagen, PGLA, etc.) | Clinical Applications (or Other Columns)? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apligraf® | Organogenesis, Canton, MA, USA | Allograft | Neonatal foreskin-derived keratinocytes and fibroblasts with bovine Type I collagen | Management of serious wounds (i.e., ulcers) |

| DermACELL | Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA | Allograft | Human tissue matrix | Management of serious wounds |

| Dermagraft® | Organogenesis, Canton, MA, USA | Allograft | Human fibroblasts seeded on polyglactin scaffold | Management of serious wounds |

| EpiFix | MiMedx, Marietta, GA, USA | Allograft | Dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane | Management of serious wounds |

| Grafix® | Osiris Therapeutics, Inc, Columbia, MD, USA | Allograft | Cryopreserved human placental membrane | Management of serious wounds |

| Hyalomatrix | Anika Therapeutics, Bedford, MA, USA | Synthetic | Hyaluronic acid (HA) in fibrous form with an outer layer comprised of a semipermeable silicone membrane | Management of serious wounds |

| Integra Bilayer Wound Matrix Dressing | Integra, Plainsboro, NJ, USA | Xenograft | Cross-linked bovine tendon collagen and glycosaminoglycan and a semi-permeable polysiloxane (silicone layer) | Management of serious wounds |

| MicroLyte AG | Imbed Bioscience, Madison, WI, USA | Synthetic | Bioresorbable polyvinyl alcohol with a polymeric surface coating containing ionic and metallic silver | Management of minor (cuts, abrasions, etc.) and serious wounds |

| NovoSorb BTM | PolyNovo, Port Melbourne, Australia | Synthetic | Polyurethane | Management of serious wounds |

| Oasis® Wound Matrix | Smith & Nephew, Fort Worth, TX, USA | Xenograft | Porcine-derived extracellular matrix | Management of serious wounds |

| TheraSkin® | Misonix, Farmingdale, NY, USA | Allograft | Human split thickness skin | Management of serious wounds |

| Clinical Indication | # of Wounds | Patient Demographics | Treatment Method | Outcomes | Adverse Events | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic wounds (DFUs, VLUs, PUs, traumatic and postsurgical wounds, non-venous vascular wounds, necrotic wounds) | 82 | 48% male; average patient age 72 years; average wound age 36 weeks; average wound surface area 3.4 cm2 | Multiple applications of the synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as needed for up to 12 weeks | 85% complete wound closure at 12 weeks and significant reduction in local inflammation | None | [31] |

| Recalcitrant neuropathic foot ulcers | 4 | 100% male; patient age range 67–73 years | Weekly, or as appropriate, treatment with synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix followed by adjunctive therapy | 75% complete wound closure and successful limb preservation | None | [32] |

| DFUs, VLUs, TMAs, PUs, partial ray amputation, neuropathic ulcers | 23 | 80% male, average patient age 63.7 years | Average number of applications was 1.2 | 96% wound closure at 95.1 days. Some wounds were also treated with NPWT and/or STSG | Wound dehiscence (1) | [33] |

| DFUs | 24 | 90% male; average patient age 55 years; average ulcer duration 16 weeks; average ulcer surface area 4.4 cm2 | Weekly, or as appropriate, treatment with synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix for up to 12 weeks | 75% complete wound closure at 12 weeks | None due to synthetic matrix | [34] |

| Chronic wounds (DFU, VLU, PUs, Charcot foot deformity) | 5 | 80% male; average patient age 66 years; average ulcer duration 51 months | Multiple applications of the synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as needed in conjunction with NPWT | Formation of granulation tissue, coverage over exposed structures, and reduction in wound size | None | [35] |

| PUs | 11 | 64% male; average patient age 55 years; | Single application of synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as a foundation for rotational skin flap | Successful granulation tissue formation and preparation of wound site for flap reconstruction, with eventual wound closure rate of 90.9% | None | [36] |

| Chronic wounds (DFUs, VLUs) | 23 | 60% male; average patient age 68 years; average ulcer duration 16 months | Weekly, or as appropriate, treatment with synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix | 96% complete wound closure at 21 weeks | None due to synthetic matrix | [37] |

| Transmetatarsal amputations, Lisfranc amputation, Metatarsal/partial ray amputations | 9 | 56% male. Patient age rand 52–68 years | Single application of synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix | 78% wound closure. The synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix was utilized in conjunction with NPWT, STSG, and amniotic tissue. | Wound dehiscence (1), Infection (1) | [38] |

| TMA wounds | 20 | 85% male; average patient age 62 years | 10 wounds treated with synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix to augment closure of the suture line and 10 control nonaugmented wounds with standard primary closure | 80% complete wound closure following treatment with synthetic matrix; reduced time to healing (18%), compared to control | Wound dehiscence (5), limb loss (2) | [39] |

| Post-Mohs wounds | 4 | 75% male; average patient age 78 years; average ulcer surface area 11.5 cm2 | Multiple applications of the synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as needed | 100% complete wound closure in 8 weeks with no scars or skin deformities | None | [40] |

| Peroneal tendon healing | 12 | 25% male; patient age range 18–75 years | Peroneal tendon repair augmented with synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix | Significant reduction in pain and rapid return to normal activity | None | [41] |

| Complex cutaneous wounds (calciphylaxis lesion, abdominal fistula lesion, necrotizing fasciitis lesion) | 3 | 67% male; patient age range 30–54 years | Multiple applications of the synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as needed in conjunction with NPWT | Significant re-epithelialization and healing of the wounds and economic cost savings | None | [42] |

| Traumatic crush injury wound | 1 | 24-year-old male | Single application of synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as a foundation for STSG | Successful granulation tissue formation and preparation of wound site for STSG | None | [43] |

| Hematomas | 2 | 50% male, patient age ranges 59–82 | Multiple applications of the synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix as needed. Used in conjunction with NPWT for one patient | 100% wound closure at an average of 77 days post initial treatment | None | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

MacEwan, M.; Jeng, L.; Kovács, T.; Sallade, E. Clinical Application of Bioresorbable, Synthetic, Electrospun Matrix in Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10010009

MacEwan M, Jeng L, Kovács T, Sallade E. Clinical Application of Bioresorbable, Synthetic, Electrospun Matrix in Wound Healing. Bioengineering. 2023; 10(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacEwan, Matthew, Lily Jeng, Tamás Kovács, and Emily Sallade. 2023. "Clinical Application of Bioresorbable, Synthetic, Electrospun Matrix in Wound Healing" Bioengineering 10, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10010009

APA StyleMacEwan, M., Jeng, L., Kovács, T., & Sallade, E. (2023). Clinical Application of Bioresorbable, Synthetic, Electrospun Matrix in Wound Healing. Bioengineering, 10(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10010009